The New Hampshire House of Representatives voted to pass its version of the State Budget on April 11, proposing to shift significant resources to education and health services during the next two fiscal years. Using the Governor’s proposal as a basis, the House budget would enhance State support for local public education, public higher education, services for those with developmental disabilities and mental health needs, affordable housing, and housing assistance services. The House budget funds these services in part by relying on surplus dollars from the current biennium and expand existing tax revenue sources, as well as removing many of the one-time expenditures and capital projects included in the Governor’s proposal. The House replaced the Governor’s voluntary paid leave program with a statewide paid family and medical leave insurance plan. The House budget adds child protection workers, building on the Governor’s proposed additions, and boosts funding for transportation. With a relatively strong economy and a revenue surplus, New Hampshire policymakers have an opportunity to comprehensively address long-term challenges facing the state and build a more resilient economy for all Granite Staters. The House version of the budget takes key steps toward addressing some of those long-term challenges.

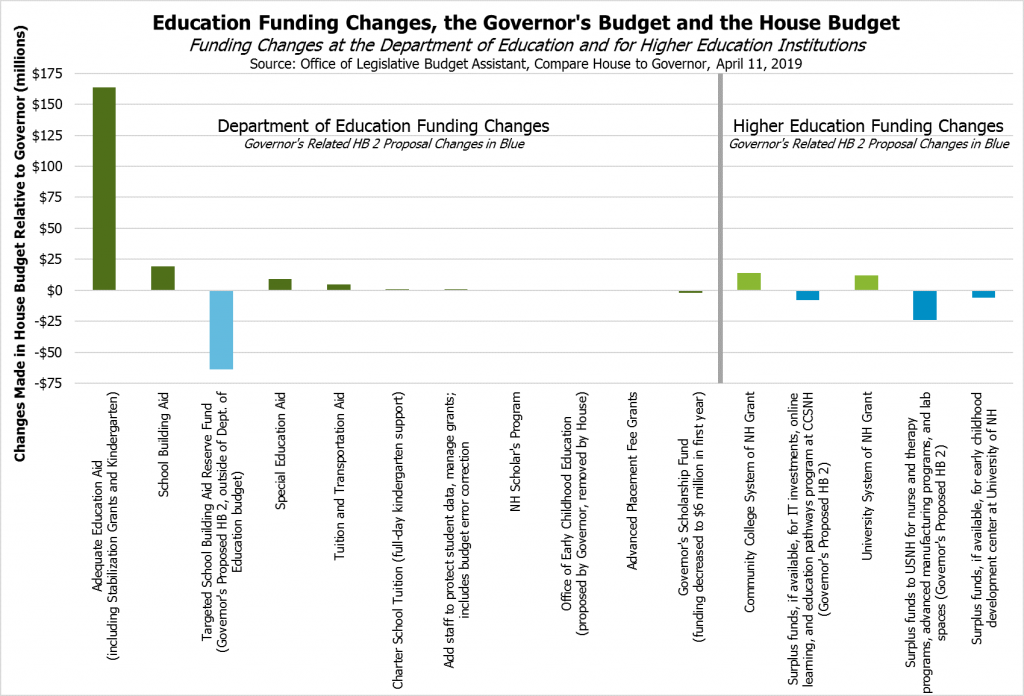

The House budget would provide additional support targeted at communities that have the most constrained abilities to fund education at the local level. The House budget would deploy an additional $165.3 million to local public education over the biennium, directing the additional aid to communities with low property values per student and higher percentages of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals. These communities either have a limited property tax base from which they can draw to fund education locally, a relatively large number of students who are from households in or near poverty, or both. Funds to support these communities with limited means would be raised by expanding an existing tax to include capital gains, which are disproportionately received by individuals with high overall incomes. The House budget would also provide school building aid, although less overall than proposed by the Governor, and increase State aid for kindergarten students.

The House budget retained many of the proposals made by the Governor surrounding mental health, although it reduced funding for the proposed construction or renovation of facilities aimed at serving mental health patients. Both the Governor’s and the House proposals show a clear commitment to eliminating the wait for services for those with developmental disabilities. The House budget would make some effort to increase reimbursement rates for Medicaid service providers, but the increases would be limited and only for certain services.

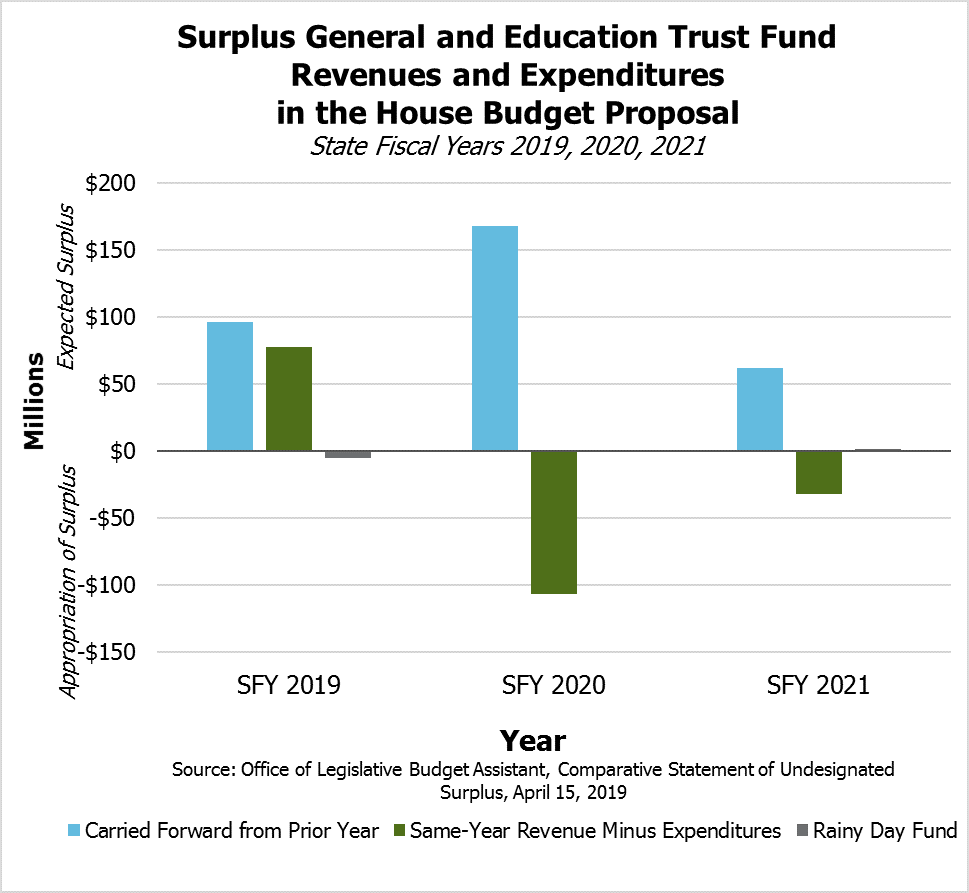

While the House budget increases revenues for needed services and expands existing revenue sources in a manner that limits the impact on low-income individuals, it also relies on existing surplus dollars to balance in both years of the biennium, creating potential challenges for funding services in the next budget as one-time revenues dissipate and economic growth is less certain.

This Issue Brief explores key components of House budget, including both the House Operating Budget Bill (House Bill 1) and Trailer Bill (House Bill 2) proposals.[1]

Overall Figures and the Big Picture

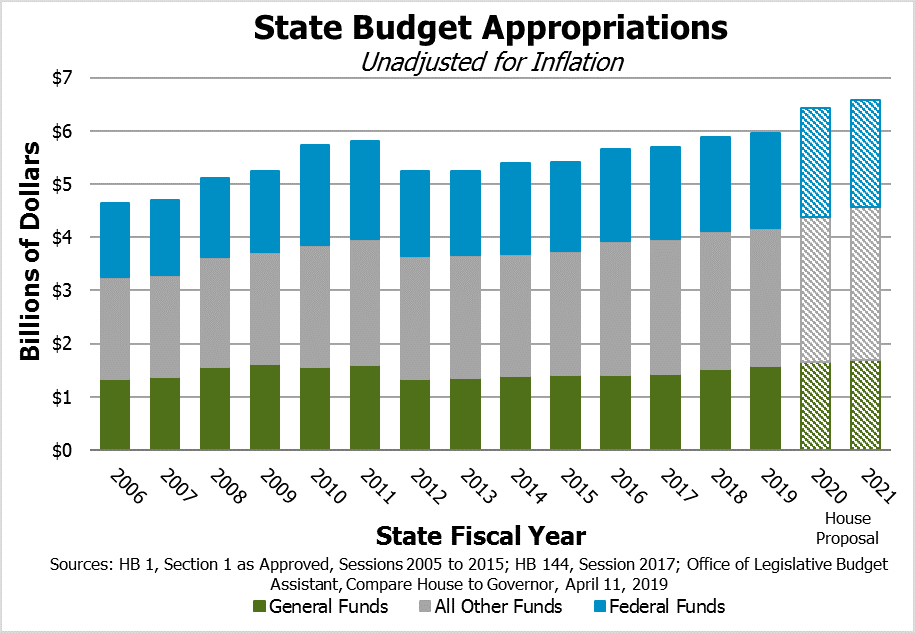

The House Operating Budget Bill would expend $13.413 billion during State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2020 and SFY 2021. However, the House removed approximately $201 million each year in double-counting of interagency transfers, bringing the total to $13.011 billion for the two-year period. Using these two figures and not adjusting for federal funds removed from the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget, this biennial budget proposal grows 13.1 percent without the removal of double-counted appropriations and 9.8 percent with those appropriations included. The Governor’s Operating Budget Bill for SFYs 2020-2021 grew 10.4 percent relative to the prior budget as passed. On a year-over-year basis and including double-counted funds, the House budget proposal would grow 8.3 percent from SFY 2019 as currently authorized to SFY 2020, and 2.3 percent between SFY 2020 and SFY 2021. Considering only the General Fund portion of the House budget, the House proposal would increase by 7.5 percent for the biennium over the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget’s General Fund, which is smaller than the 9.2 percent the prior State Budget’s General Fund increased relative to its predecessor.[2]

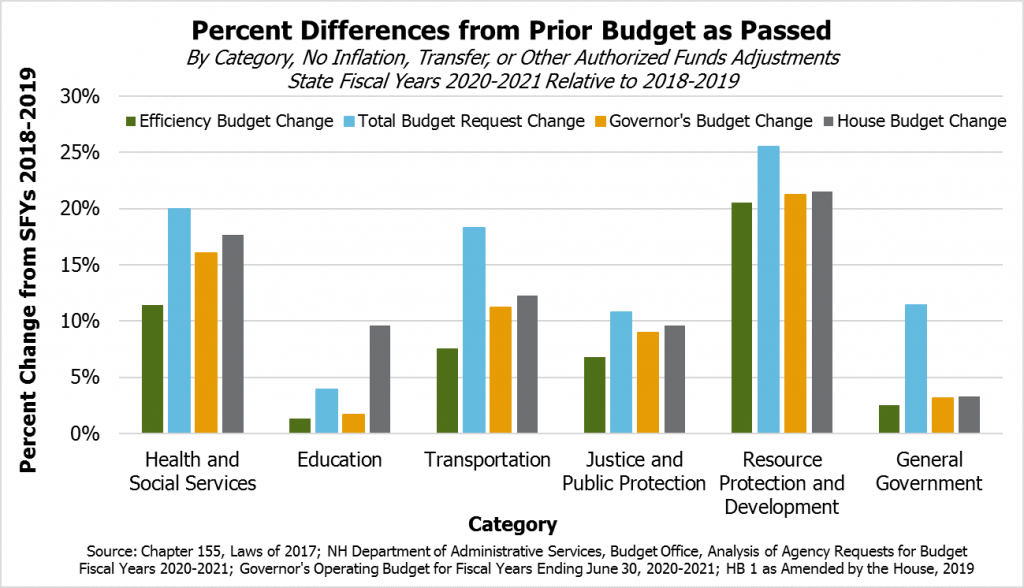

The House Operating Budget Bill, similar to that of the Governor, funds most categories of State services at levels between State agency Efficiency Budget requests for the biennium and the Total Budget Requests from State agencies, which include State agency priorities categorized as Additional Prioritized Needs.[3] The key exception is Education, where the House budget added significant new funding to local public education aid and public higher education. All other categories were appropriated more incremental increases in the House budget relative to the Governor’s proposal, and in no other instance did the House budget exceed the growth in the Total Budget Requests from agencies operating in categories of State services. Comparisons to the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget discussed here do not adjust for federal and other funds removed by the Legislature from the last State Budget, nor do they adjust for the inclusion in the SFYs 2020-2021 agency requests, the Governor’s proposal, and the House budget of a major water infrastructure-related fund under Resource Protection and Development that was operating but not accounted for in the prior State Budget. These figures also do not account for the surplus dollars that would be deployed by the Governor’s or the House proposals in the Trailer Bill and outside of the Operating Budget Bill.

Funding Public Services

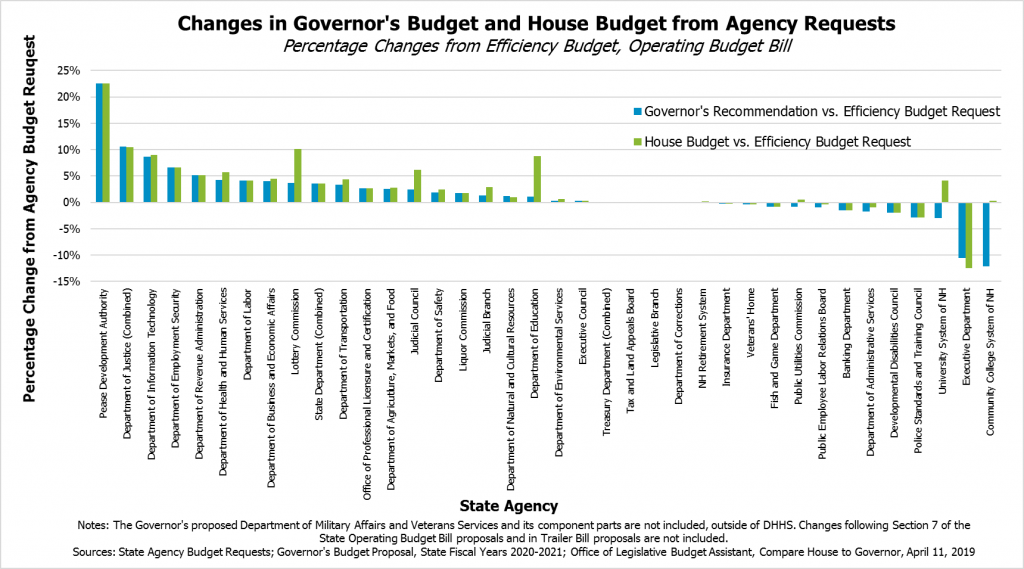

Although both the Governor’s budget and the House budget increase funding for State services overall, some agencies were funded at lower levels than the amounts requested in their Efficiency Budget proposals. Both the House and the Governor opted to fund the Department of Justice, the Department of Information Technology, New Hampshire Employment Security, the Department of Revenue Administration, and the Department of Health and Human Services significantly above levels requested in their Efficiency Budgets. The primary relative differences between the Efficiency Budget Request, the Governor’s proposal, and the House budget appear in the Department of Health and Human Services, the Lottery Commission, the Judicial Council, the Department of Education, the University System, and the Community College System. Both the Governor and the House agreed in their proposals to move the Governor’s Scholarship Program out of the Executive Department, which accounts for the large decreases relative to the Efficiency Budget. The House budget would add ten new positions to the Lottery Commission and appropriate funding to assist with the administration of legalized sports betting. Changes to the Judicial Council’s funding levels stem primarily from the House budget proposing to fund both the Public Defender Program and the Civil Legal Services Fund, which supports the work of New Hampshire Legal Assistance to provide legal services to low-income individuals, at higher levels than in the Governor’s proposal. Notably, these comparisons do not include the Governor’s or the House’s proposed deployment of surplus dollars in the Trailer Bill to State agencies, as they are outside of the Operating Budget Bill proposals and are not necessarily allocated to State agency funding levels.

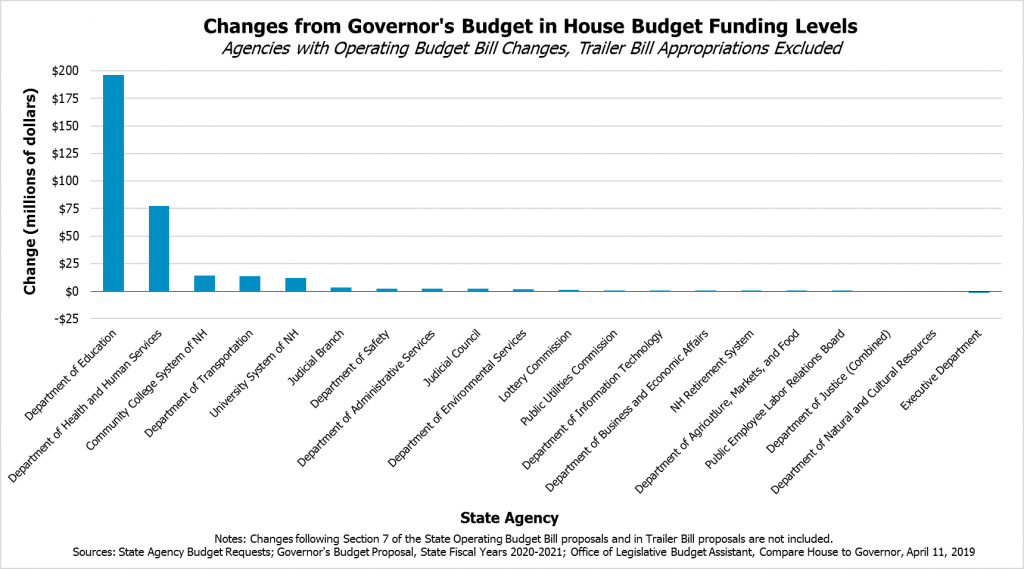

In dollar terms, the largest funding changes the House budget would make relative to the Governor’s budget are increases in the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services. Those increases are followed by significant new appropriations to the Community College System of New Hampshire, the Department of Transportation, and the University System of New Hampshire relative to the Governor’s budget proposal. Three agencies (the Department of Justice, the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, and the Executive Department) were funded at lower levels in the House budget than in the Governor’s proposal. Nineteen State agencies saw no change in funding between the two budget proposals.

Education

The House budget proposes major additional investments in education. The House appropriated additional operating grants to public higher education, rather than offering funding for specific initiatives or projects, and used the existing school building aid formula to provide aid to local school infrastructure. Most critically, the House voted to send significantly more resources to school districts that have lower property values per student or that have higher percentages of students with low incomes.

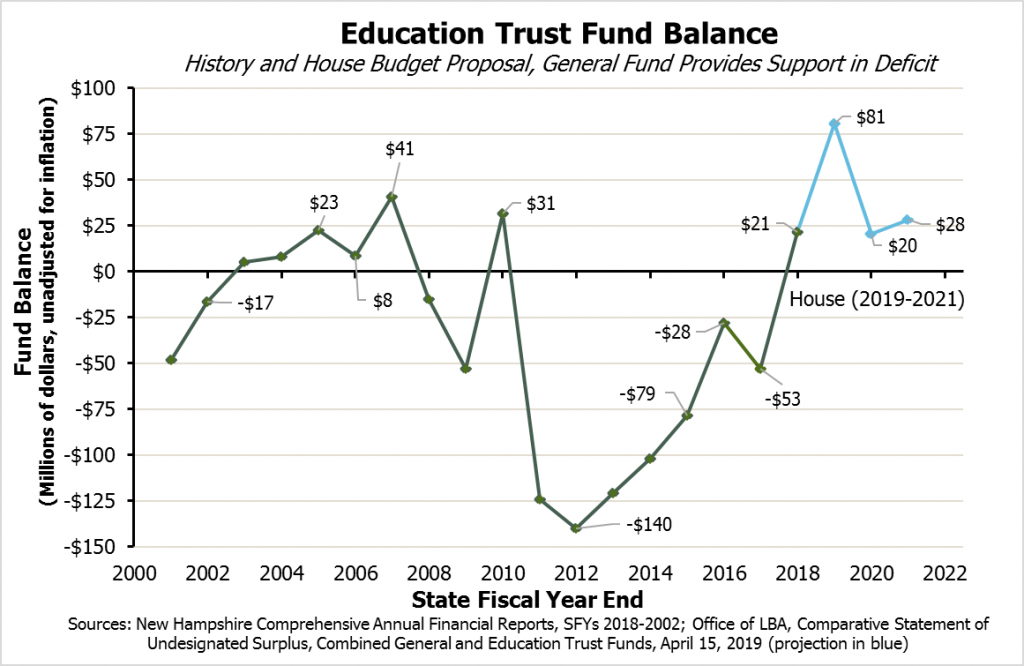

In a key decision for comparing budgeted education aid, the House retained the Education Trust Fund, which holds the State Adequate Education Aid funds provided to local public schools. The Governor’s budget proposed eliminating the Education Trust Fund as an entity and moving the supporting revenue streams into the General Fund and the Sweepstakes Fund; this proposal would not have changed the amount of aid to public schools. In the House plan’s projections, the Education Trust Fund retains a surplus during the biennium, ending SFY 2021 with $28.02 million.

Adequate Education Payments to Local Public Schools

The House voted to substantially increase State support for local public schools. This support comes primarily through Adequate Education Aid, which is currently provided by the State on a per pupil basis, with certain upward adjustments for students with special education needs, English language learners, students eligible for the Free and Reduced-Price School Lunch Program, and students ineligible for other upward adjustments who scored below proficient on the State Third Grade Reading assessment. The base Adequate Education Aid amount for SFY 2020 is $3,708.08 per pupil, with upward adjustments ranging from an additional $725.63 per pupil identified as an English language learner to $1,995.21 for a special education student.[4] School districts reported a statewide average operating cost per pupil of $15,865.26 for the 2017- 2018 school year, with the inclusion of certain tuition, transportation, capital items, debt payments, and facility construction and acquisition bringing the average per pupil cost to $18,901.32.[5]

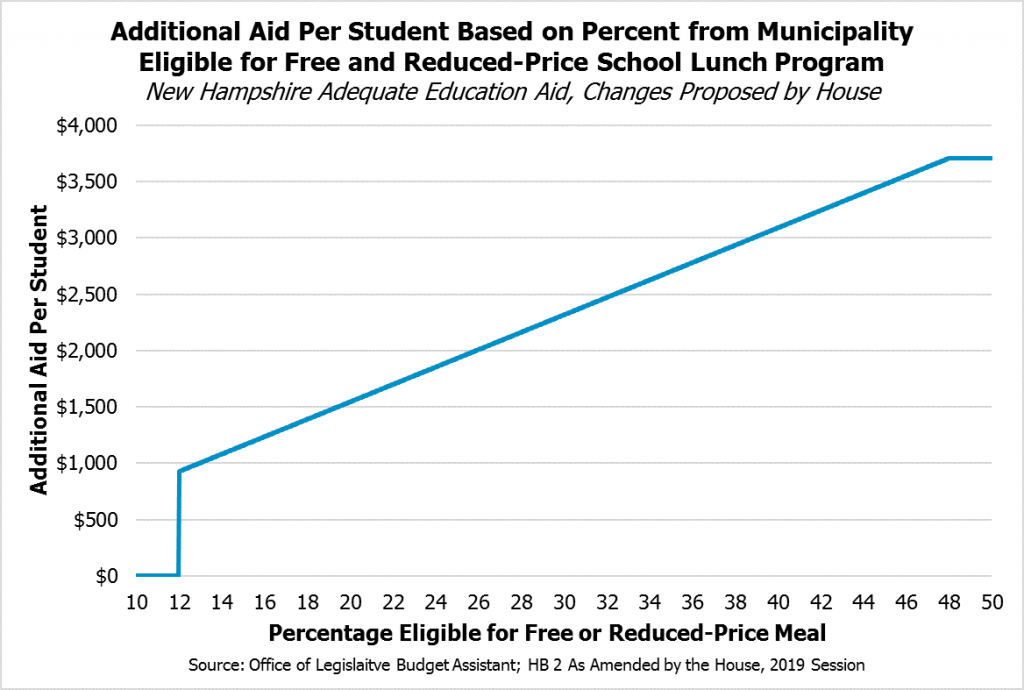

The House would augment the existing Adequate Education Aid formula by adding additional aid for schools with higher percentages of free and reduced-price school meal eligible students and for school districts with less property value per pupil. For school districts with 48 percent or more students eligible to receive a free or reduced-price meal, an additional $3,708 would be provided for each pupil eligible, essentially doubling the base adequacy amount provided for those pupils. In October 2018, sixteen school districts had more than 48 percent of students eligible for the Free and Reduced-Price School Lunch Program, including Stratford, Winchester, Manchester, Franklin, Laconia, Berlin, Claremont, Newport, Pittsfield, and Farmington. School districts with less than 12 percent of their students eligible for free or reduced-price meals would not see an increase in aid under the House proposal, and districts with between 12 percent and 48 percent of pupils eligible would receive at least $927 and up to $3,707.23 per eligible student, based on a sliding scale calculation.

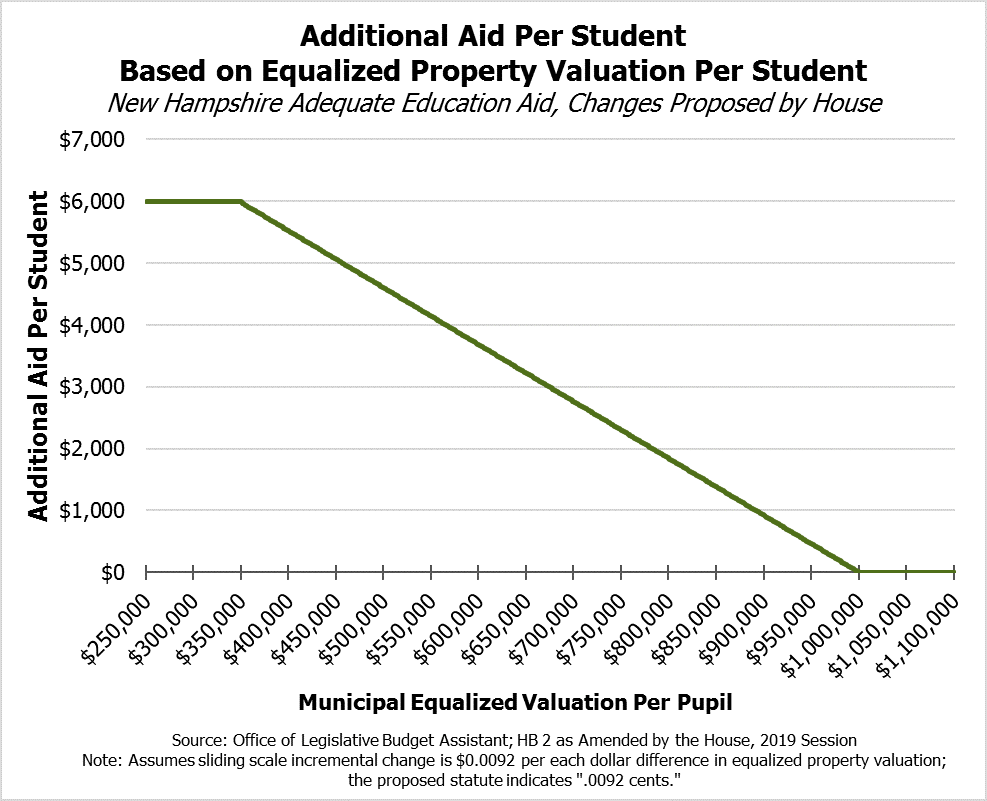

Additionally, the House budget proposes adding an additional grant of $6,000 per student for a municipality’s school districts where the equalized property valuation per pupil is at $350,000 or less. In 2017, the equalized valuation per pupil was lower than $350,000 only in Berlin. Additional fiscal capacity aid would be distributed based on property values per pupil for municipalities with over $350,000 in valuation per pupil, falling on a sliding scale to $0 for municipalities with a valuation per pupil of $1,000,000 or greater. The statewide equalized valuation per pupil in 2017 was $1,043,647.[6]

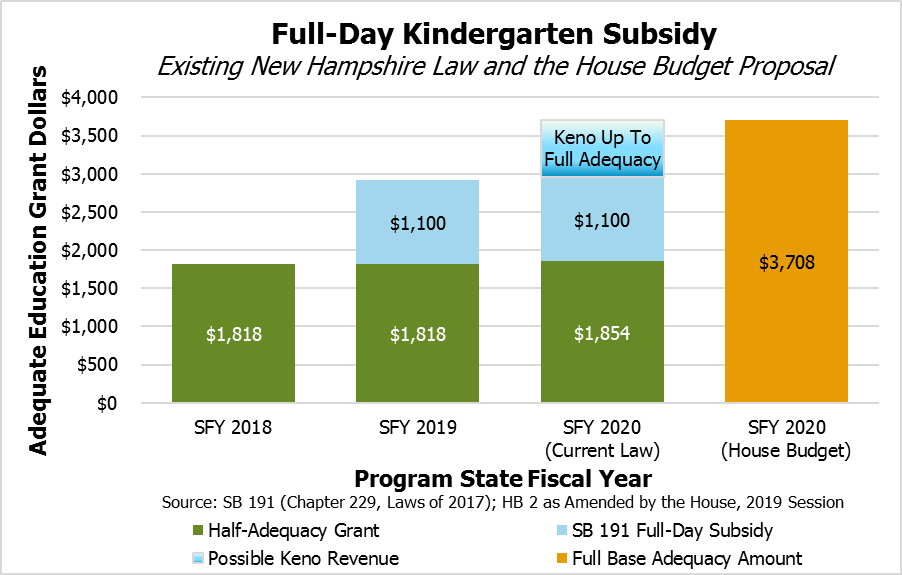

The House would include kindergarten students fully into the Adequate Education Aid formula. Currently, kindergarten aid is set at half of the base Adequate Education Aid amount, or $1,818.03 in SFY 2019 and $1,854.04 in SFY 2020, with an additional $1,100 provided per pupil in SFY 2019. Starting in SFY 2020 under current law, additional aid up to the full Adequate Education Aid amount would be provided dependent on Keno revenue, with $1,100 guaranteed to be provided. The House budget, starting with SFY 2020, would fund kindergarten students at the same level, and using the same differentiated aid factors for upward adjustments, as students in grades one through twelve.[7]

While the additions to the Adequate Education Aid funding formula would take effect in SFY 2021, the House budget would restore the full stabilization grant amount from SFY 2016 to local governments in SFY 2020. Stabilization grants, instituted in SFY 2012 after the last major Adequate Education Aid formula revisions, declined at four percent of their original values each year starting in SFY 2017. Stabilization grants would be eliminated under the House budget in SFY 2021, supplanted by the new formula changes. Once the new formula changes take effect, Adequate Education Aid would be limited to a 20 percent increase in aid per municipality from the prior year in SFY 2021 and 2 percent growth in each subsequent year, and most municipalities would not receive less funding than the previous year.[8]

Increased kindergarten aid and the increased stabilization grants would together contribute an estimated additional $34.8 million in SFY 2020 under the House budget. The additions to the Adequate Education Aid funding formula for students eligible for free and reduced-price meals and for fiscal capacity disparities based on property values, combined with the increased kindergarten aid, would add about $130.5 million in Adequate Education Aid in SFY 2021 relative to current law.[9] The House budget would also add explicit Adequate Education Aid use and reporting requirements for school districts in statute.

The House budget would appropriate $500,000 to fund a commission to study school funding, including “whether the New Hampshire school funding formula complies with court decisions mandating an opportunity for an adequate education for all students, with a revenue source that is uniform across the state” and identifying trends and disparities in student performance. Funding for the commission would support staffing independent of government agencies as well as the utilization of independent school finance experts.

School Building Aid and Other Education Aid

The House voted to lift the current moratorium on accepting new school building aid projects and provide an additional $19.3 million through the existing program. The school building aid program has not accepted new projects since SFY 2010 with one exception, but has been paying for the costs of past projects since the moratorium, with diminishing appropriations over time. The Governor budgeted $32 million in SFY 2020 and $30 million in SFY 2021 to support this ongoing commitment. The House moved these appropriations to draw from the Education Trust Fund and appropriated $38.7 million in SFY 2020 and $42.6 million in SFY 2021, with a total $19.3 million increase over the biennium. Notably, the House did not vote to retain the Governor’s proposed Targeted School Building Aid Reserve Fund, which would have appropriated $63.7 million from the Education Trust Fund for school building aid dispensed under the direction of State officials in a new structure established by the Governor’s Trailer Bill proposal while the existing school building aid program remained suspended.

In addition to the changes to the Adequate Education Aid formula, the House voted to draw from the Education Trust Fund and send funds to local schools for education-related aid to:

- fully fund anticipated special education for students who have higher cost needs, with an additional $9 million of funding above the boost of $4 million proposed by the Governor

- provide an additional $4.6 million in tuition and transportation aid to school districts, aimed at fully funding anticipated tuition and transportation aid to school districts

- support public charter school tuition for full-day kindergarten with an additional $820,648, although building lease aid for SFY 2020 was reduced by $300,000 following an amendment on the House floor

The House budget adds one information technology staff member to help manage and protect the security and privacy of student data, and does not fund staff associated with the Governor’s proposed Office of Early Childhood Education. The House budget also reduced the State grants to pay for student Advanced Placement test fees from $250,000 per year to $100,000 per year. The House budget retained the Governor’s proposal to move the Governor’s Scholarship Program, which provides up to $2,000 in scholarship aid per eligible student or resident meeting certain requirements and seeking to attend post-secondary educational institutions in the state, from the Governor’s Office of Strategic Initiatives to the Department of Education; however, the House would reduce funding levels relative to the Governor’s proposal for the Scholarship Program from $8 million to $6 million in SFY 2020, retaining the $8 million proposed for SFY 2021. The House budget adds $100,000 per year in funding to the New Hampshire Scholars Program, which focuses on a rigorous core curriculum and facilitates coordination between high schools and businesses.

Public Higher Education Aid

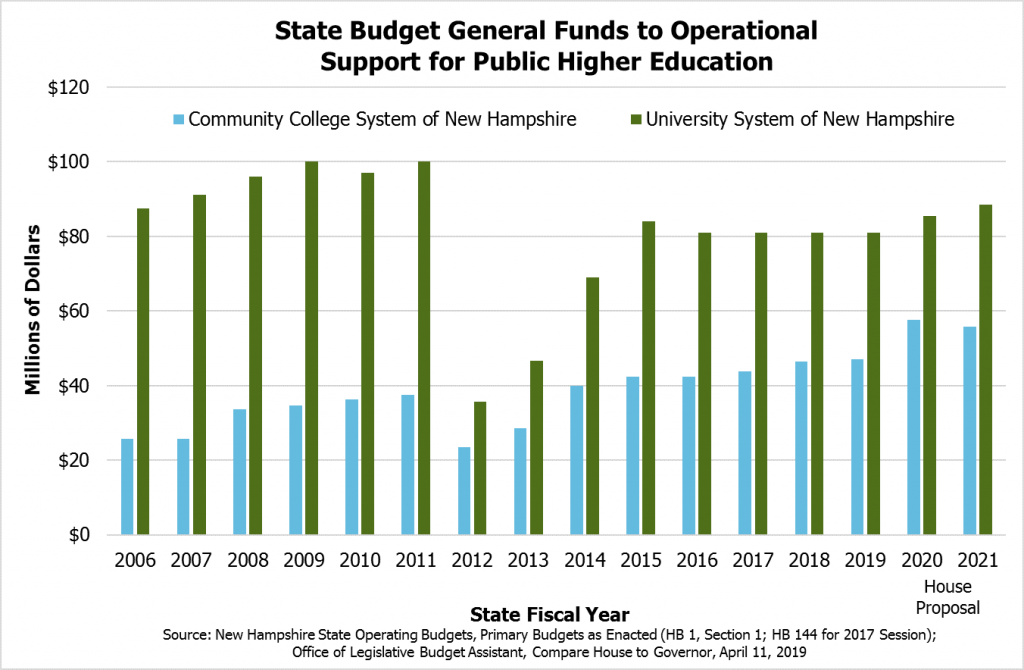

The House voted to appropriate more General Fund operating grant dollars to both the Community College System of New Hampshire and the University System of New Hampshire.

Under the House’s proposal, the Community College System would receive an additional $19.965 million more than the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget, which was $14.1 million more than the Governor proposed in his State Budget. The Community College System would receive $57.705 million in SFY 2020 and $55.81 million in SFY 2021. The House did not not carry forward the Governor’s proposed $7.75 million surplus-contingent appropriation for information technology infrastructure investments, online learning, and to implement an industry-wide education pathways program at the Community College System. The Governor’s Finish Line New Hampshire Scholarship Program, which would help 25-year-old and older students in the Community College System taking coursework in areas identified as in high demand finish their degrees with tuition grants, is also included in the House budget.

The University System would receive an increase in operating funding support of $12 million relative to the current biennium. This funding increase would be the first time the University System received more than $81 million in General Fund support from the State since SFY 2015, when it received $84 million for one year. The House budget does not include the $24 million in one-time, directed funds for the University System aimed at bolstering the health care and manufacturing workforce as well as supporting capital projects at Plymouth State University, or the $6 million in surplus-contingent funds to create an early childhood development center on the University of New Hampshire campus, proposed in the Governor’s budget.

Health and Human Services

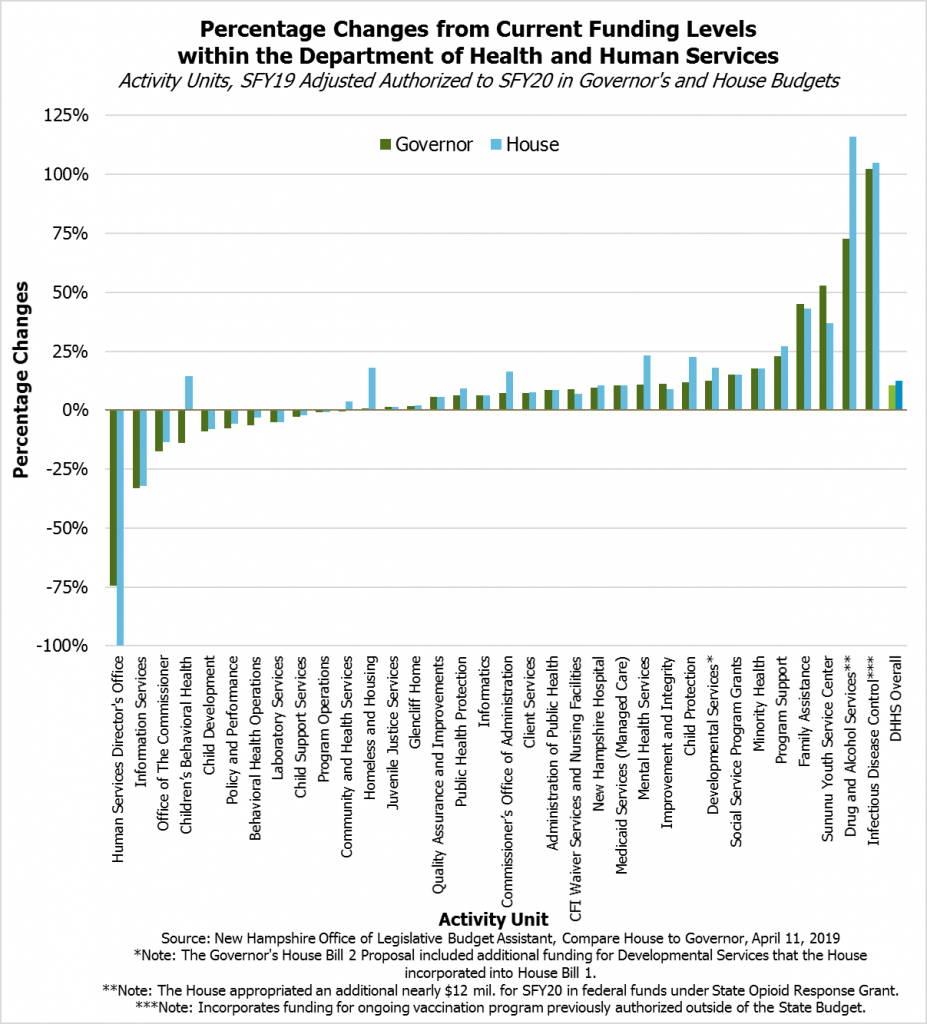

The House budget substantially invests in health care services and social assistance, with major funding changes in Medicaid-supported programs. The House budget would fund the services included in the SFY 2020 Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) budget 12.6 percent higher than those services in SFY 2019, which is slightly higher than the Governor’s proposed increase of 10.7 percent across the same two years. Throughout the biennium, the House budget proposes $77.3 million to fund additional services provided by the DHHS beyond the Governor’s proposal; however, that comparison does not include several of the DHHS-related Trailer Bill expenditures the Governor proposed making with surplus dollars in SFY 2019, such as $26 million for the secure psychiatric hospital, $20 million for services for those with developmental disabilities, and other expenditures.

Developmental Disability Services

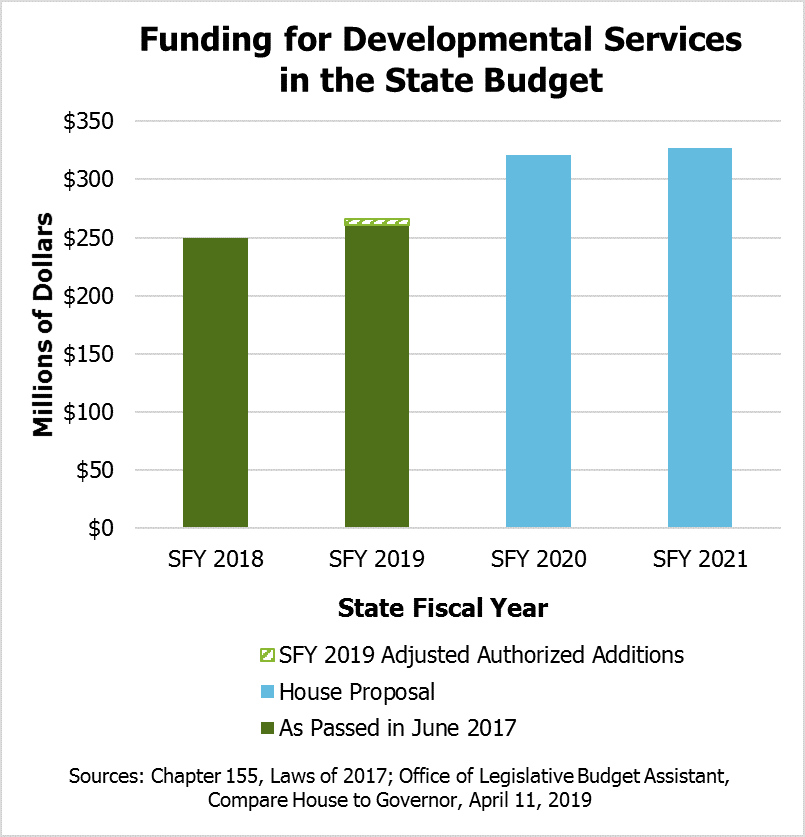

Medicaid funding to services for those with developmental disabilities was one of the single largest dollar-value investments made in the House budget proposal relative to the current operating budget. Like the Governor’s budget proposal, the House aims to eliminate the projected wait list for services in SFY 2020 and provide a 2.5 percent reimbursement rate increase to service providers.

The House budget funds these services at the same levels as the Governor’s proposal, but does so in a slightly different fashion. The Governor budgeted for $10 million in General Fund surplus dollars in SFY 2019 to be used in SFY 2020, whereas the House budget brings those surplus dollars into SFY 2020 and includes the Medicaid match in the budgeted appropriations.

The proposed increase for the biennium over the funded levels provided for in the current budget, as passed in June 2017, is approximately $137.8 million; about half of these additional funds are federal funds provided through the Medicaid program. For context, this dollar figure is larger than the expected increase in Adequate Education Aid funded through the House budget’s revised formula for distributing grants in SFY 2021. These recommendations by the Governor and the House show a shared commitment to investing in this population and seeking to eliminate the wait for services.

Mental Health

The House budget voted to appropriate $1.225 million for the planning and engineering design to repurpose space at New Hampshire Hospital, currently used by children and other patients who no longer need the level of care offered at New Hampshire Hospital, or to construct or renovate a new forensic psychiatric facility for individuals currently civilly committed to the Secure Psychiatric Unit. The direction of these funds would be determined, no later than June 1, 2020, by the DHHS in consultation with a new advisory council on civilly committed patients. The advisory council would be required to submit an annual report each November from 2019 to 2022. The House did not fund the Governor’s proposal to appropriate $26 million to build a new 60-bed forensic psychiatric hospital.

The House budget proposal would add $3 million in funding for a fourth mobile crisis unit. Mobile crisis units can respond to mental health crises on location and within a short period of time, and can provide services for several days after a crisis. The House budget would also appropriate $2 million for children’s mobile crisis teams, which may be integrated with adult mobile crisis units.

Relative to mental health during the biennium, the House budget would appropriate:

- $5 million for an inpatient psychiatric treatment facility, as recommended by the Governor

- $4 million for repurposing the children’s unit at New Hampshire Hospital to support adult beds, similar to the Governor’s budget proposal but with the $1.225 million for planning and designing renovated space at New Hampshire Hospital or new space to be constructed or renovated to be drawn out of this total

- $2.5 million for 20 transitional housing beds, a reduction from the Governor’s proposed funding level of $5 million for 40 new beds, with a focus on providing space for those transitioning out of New Hampshire Hospital

- an additional $2.1 million for community housing and related supports under the Community Mental Health Program

- $2 million to fund rate increases for, and the construction of, designated receiving facility beds in SFY 2020, as was recommended by the Governor

- $1.5 million to fund service options for those individuals who do not need institutional care but are not yet ready for independent living

- $1 million in statewide early serious mental health intervention services

- $1 million in immediate assistance to hospitals to help with the needs of patients in hospital emergency rooms, mirroring the Governor’s proposal but requiring that no hospital receive more than $100,000 and that the hospitals receiving the funds be more than 30 miles from a designated receiving facility or mobile crisis team

- $900,000 for suicide prevention activities, including a nationally-accredited suicide hotline service based in New Hampshire

- $641,056 for four DHHS program specialist positions to support implementation of the Ten Year Mental Health Plan

Substance Misuse

The House budget accounts nearly $12 million in additional federal funding awarded in SFY 2019 under the State Opioid Response Grant. This funding would be deployed through the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services. The House budget retained the Governor’s appropriation of $10 million per year to the Bureau from the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse, Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery. This funding likely reflects the use of anticipated voluntary donations from hospitals to the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund. The House budget would explicitly require that any contributions to the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund by hospitals in New Hampshire be used to fund alcohol and other drug abuse prevention, treatment, and recovery services.

The House budget removed the policy change, proposed in the Governor’s budget, that would have added protections for those individuals with life, life annuity, and disability insurance. The language would have prevented companies from denying or disenrolling an individual from coverage, or limiting their coverage, solely because the individual filled a prescription for naloxone, a medication used to block the effects of opioid overdoses.

Child Services and Protection

The House budget adds nearly $3.16 million in State and federal funds to the Governor’s budget proposal over the biennium to fund 25 positions at the Division of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) in addition to the Governor’s proposal, including 14 case aides and five public health nurse consultants, and another nearly $1.1 million in State and federal funds to support eight new legal services positions, including six for DCYF legal work. The House budget also includes $299,269 for two new positions to implement lead testing procedures, and $124,910 for a case technician in the Bureau of Child Support Services.

Approximately $5.5 million would be set aside to fund voluntary services for families. These services would be available before families become involved with DCYF.

The House budget funds approximately $14 million in child protection and family services in an effort to bring the state into compliance with the federal Families First Act. The funding would support residential programming and treatment services through revised rates and redesigns as well as funding a structured decision-making intake assessment under the Bureau of Child Protection. The House budget would also provide over $3.6 million to increase the age for foster care and adoption from 18 years old to 21 years old during the biennium.

Home visiting programs would receive a $706,000 increase in funding over the biennium, and school counseling programs would receive $250,000. The House budget would also appropriate $500,000 to study the high levels of pediatric cancer in New Hampshire; the Governor’s budget proposal appropriated $1.2 million out of surplus-contingent appropriations for this purpose.

The House budget would establish the Child Abuse Specialized Medical Evaluation Program. This program would provide child protective service workers with an available 24-hour connection to an experienced health care professional with training in diagnostic methods and treatment of child abuse, provide more training to child protective workers and nurses regarding child abuse, and require periodic peer or expert reviews of evaluations conducted by participating health professionals. Additionally, this program would require increasing reimbursement rates to reflect the cost of service delivery. The House budget appropriates nearly $1.5 million to fund this program.

The House budget includes an addition to laws governing commitment of minors in certain situations to require prompt evaluations for alternatives that are safe, therapeutic, and cost-effective. The new language would encourage transfers to facilities eligible for Medicaid reimbursement and bolster reporting requirements to the court system and parents or guardians of minors. Additionally, the House budget would fund the Sununu Youth Services Center at lower levels than the Governor proposed.

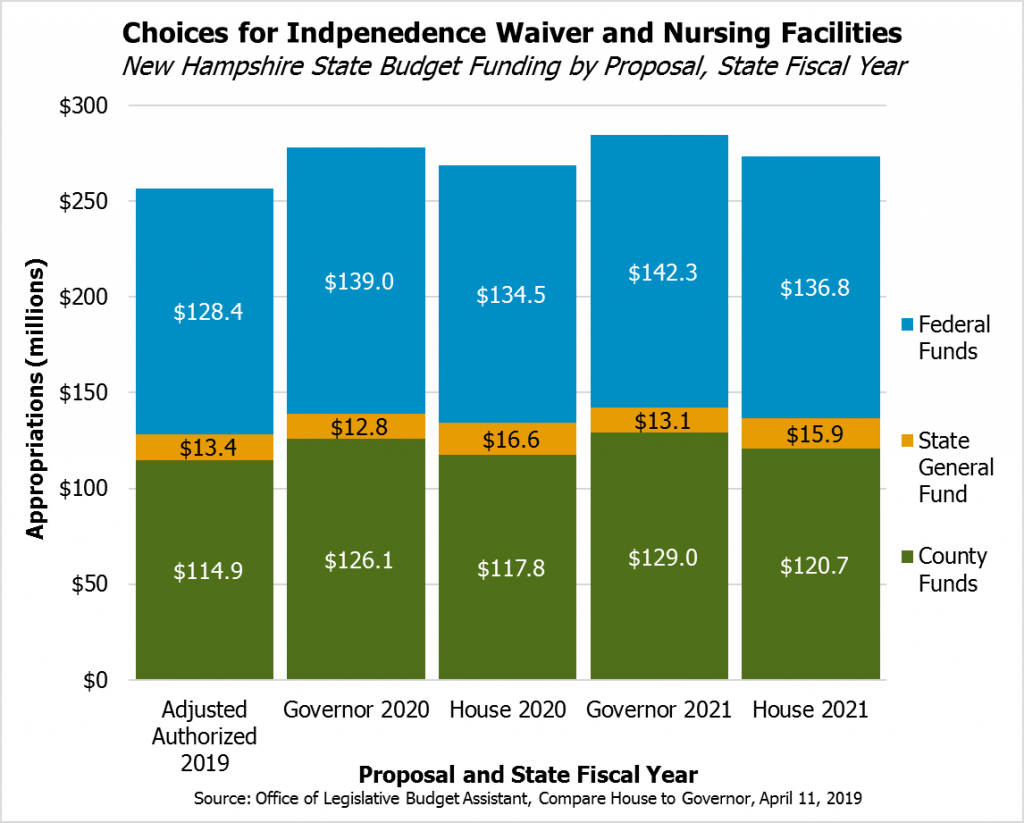

Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver and Nursing Home Services

Counties are responsible for certain long-term supports and services provided to their residents, including nursing home services and services delivered through the Choices for Independence (CFI) Medicaid Waiver. CFI Medicaid Waiver services provide long-term care coverage for eligible adults of limited means in home- and community-based settings. They are delivered through providers who are reimbursed by federal, county, and state government funds for delivering home- and community-based care. The House budget reduced funding from the Governor’s proposal by $20 million for nursing home and CFI Medicaid Waiver services, in part due to concerns about increased costs to counties, which pay for a significant portion of those services. The primary tax revenue source for counties is the property tax.

Although the Governor’s budget proposal increased funding for CFI Medicaid Waiver and Nursing Home Services overall, the amount of State General Fund support for the program in the Governor’s proposal dropped $627,965 (4.7 percent) from the levels authorized for SFY 2019 to SFY 2020, and increased $298,608 (2.3 percent) between SFY 2020 and SFY 2021. The House added nearly $6.6 million in State funds over the biennium to offset county costs. Although the total appropriation dropped by $9 million for SFY 2020 in the House budget proposal relative to the Governor’s proposal, State General Fund contributions increased by almost $3.2 million (23.6 percent) from authorized SFY 2019 levels. This increase would keep growth in county costs at about $2.9 million (2.5 percent), rather than the nearly $11.2 million (9.7 percent) proposed by the Governor, between SFYs 2019 and 2020. The Governor’s proposal would increase county costs by $2.9 million (2.3 percent) in SFY 2021 from SFY 2020, which is nearly the same as the House’s proposed increase of $2.9 million (2.5 percent).

Key service provider reimbursement rates for the CFI Medicaid Waiver program have not kept pace with relevant measures of inflation in recent years, and service providers face a shortage of available workers, who may be offered competitive wages outside of the New Hampshire Medicaid service delivery system. Raising reimbursement rates would likely help alleviate this situation and help ensure Granite Staters with a chronic illness or disability get the care they need.[10]

Dental Benefits for Medicaid Adults

The House budget would include a dental benefit for adults in the Medicaid program, permitting coverage for preventative dental services under the Medicaid program’s contracts with managed care organizations. The House funds this benefit at $5 million for the last six months of the biennium, which would provide time to plan the benefit structure.

Cliff Effects and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Funding

The House budget alters the Governor’s proposals around mitigating the benefit “cliff effect.” The cliff effect occurs when individuals on a public assistance program have an increase in income, such as from a new job, or another change in their status that makes them no longer eligible for a program, which results in a sudden end to benefits.

The Governor proposed extending Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits into the first six months of employment for an individual receiving those TANF benefits by exempting income from the first six months of employment in their benefit calculations. The House budget did not extend that benefit, but included a policy proposal to coordinate poverty reduction strategies across State agencies and employers, require the Department of Health and Human Services create a plan to close the cliff effect, create a “benefits cliff calculator” to measure the effects of increased income on individuals, and create a working group to report policy recommendations throughout the biennium.

The House budget retains the Granite Workforce program modifications proposed by the Governor. As proposed, the Granite Workforce Pilot Program would subsidize employers of participants in the Granite Advantage expanded Medicaid program for up to $2,000 for the first three months of employment, with an additional subsidy of up to $2,000 after nine months of employment. For employees enrolled in Granite Advantage and eligible for TANF, TANF dollars would be used, but the proposal also expands the Granite Workforce pilot program’s funding beyond federal TANF dollars for families not eligible for TANF services, including job training and other available appropriations. Granite Workforce participants may continue to be eligible for the program as needed if their incomes rise above the eligibility levels for the Granite Advantage program within certain limits and within a nine-month period.

TANF funds are provided through block grants of about $38.4 million per year from the federal government. The estimated balance of the TANF reserve was $70.1 million at the end of SFY 2017, but it is projected to fall to $35.6 million by the end of SFY 2019, as expanded benefits and additional appropriations of TANF dollars to other programs have drawn on the reserve. The Governor’s budget proposal would have produced a projected TANF reserve deficit of $17.4 million by the end of the biennium. The House budget would reduce that TANF deficit to about $5.8 million. TANF reserves are particularly important during times of unforeseen need, such as economic recessions, to provide temporary assistance to families who lose income.[11]

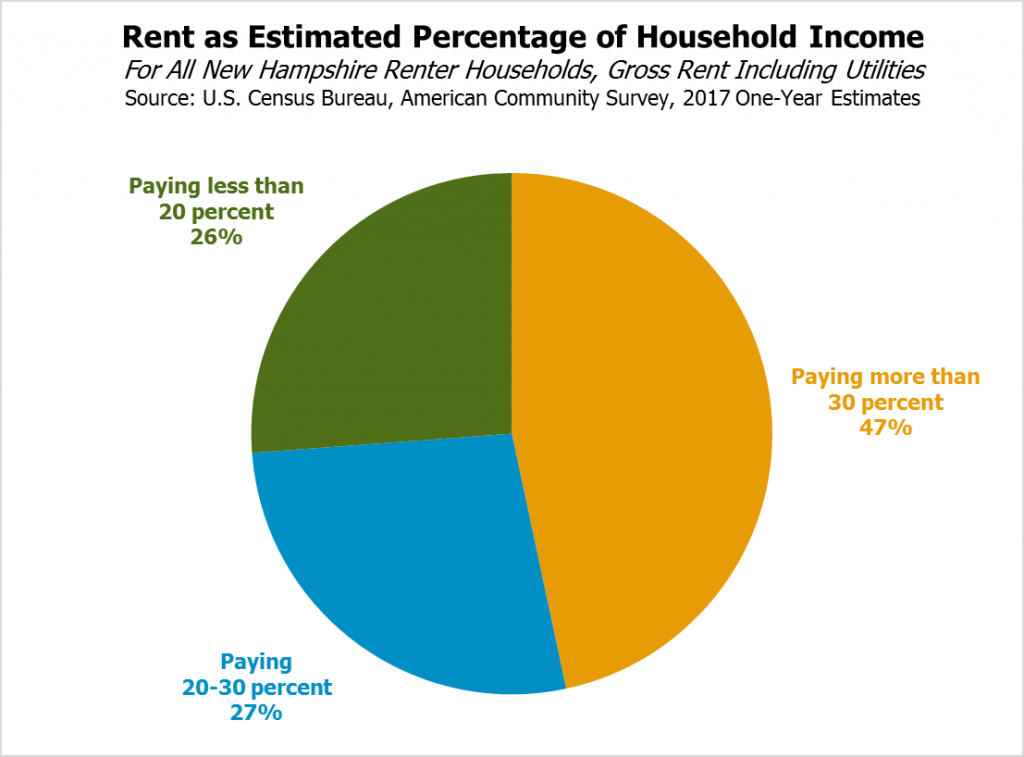

Housing

The House budget includes increases in funding for housing-related services, including those targeted at homeless individuals. The proposal includes $1 million over the biennium for homeless shelter case management programs to make connections between individuals and services, such as TANF or Food Stamp Program services or supplemental income and disability insurance. The plan would add $1.5 million for rapid re-housing programs to prevent homelessness and improve affordable and transitional housing, $2 million for eviction prevention efforts with short- and medium-term rental assistance, and $400,000 in outreach to homeless youth to aid transitions to shelters and housing.

The House budget retains the Governor’s proposal to add $5 million to the Affordable Housing Fund, although the timing of the appropriation was altered by the House. The Governor appropriated $1.5 million from the SFY 2020 surplus, to be distributed by January 2021, and $3.5 million from the SFY 2021 surplus, to be distributed by January 2022, to the Affordable Housing Fund, which provides grants and low-interest loans for building or acquiring housing affordable to families and individuals with low-to-moderate incomes.[12] The House budget appropriates $5 million to the Affordable Housing Fund for SFY 2020 from the General Fund regardless of surplus amounts and without the restriction of waiting until the surplus amounts are determined, which is dependent on an audit typically completed six months after the end of the fiscal year.

Transportation

The House budget would add nearly $13.5 million more to the Department of Transportation over the course of the biennium. Certain funding changes were due to error corrections from the prior version of the budget, but a significant amount of new funding, about $14.7 million over the biennium, is appropriated for the Department’s fleet equipment replacement program and repairs to other equipment. Savings of $2.4 million were generated by decreasing contracts for certain graffiti removal, guardrail repairs, mowing, and tree clearing services while adding three highway maintainer positions. The House budget adds $400,000 to assist public transit operators and $345,475 to study statewide snowplow route optimization and manage salt reduction. The House budget also would dedicate about $1.4 million to preventative maintenance through bridge painting and installing intelligent transportation system technologies such as traffic cameras, message boards, and weather monitoring systems.

The House budget would make several policy changes affecting funding available for transportation projects. The House voted to redirect revenue from permitted plea-by-mail submissions related to motor vehicle fines to the Highway Fund, rather than counting them as agency income for the Department of Safety. The House budget estimates this would be an additional $8.4 million for the Highway Fund per year. The House would also increase the fee for Real ID Act compliant license issuance or renewal for most drivers to $60 from $50, which the House anticipated would bring in $955,000 during the biennium for the Highway Fund.

The House budget would permit the use of Turnpike toll credits, which are projected future revenues from tolling operations, to complete the project development phase of the New Hampshire Capital Corridor design, environmental review, and financial plan for rail and bus services expansion, including parking facilities. The New Hampshire Constitution restricts use of motor vehicle gasoline taxes, and registration and license fees, to the construction, maintenance, and supervision of public highways, but does not explicitly exempt use of Turnpike tolling operations for public transit and rail purposes; the House budget would change the law to permit Turnpike toll credits to be used for these purposes.[13]

Major New Initiatives

As with the Governor’s proposal, the House budget Trailer Bill includes significant policy proposals that have budgetary impacts. These new initiatives include entirely new programs and substantial changes to existing law and State agency authority.

Paid Family and Medical Leave

The House voted to remove the Governor’s proposed Twin State Voluntary Leave Program and replace it with Family and Medical Leave Insurance in the State Budget’s trailer bill. The House’s proposed plan was previously in a separate House bill, and would not involve potential collaboration with Vermont, as the Governor’s plan proposed.[14]

The proposed Family and Medical Leave Insurance would provide up to 12 weeks of benefits for an eligible employee who has been enrolled in the program for at least six months and has worked enough to have earned total wages relative to a certain threshold based on the minimum wage within the last year, or four of the last five calendar quarters. Benefits would be 60 percent of the weekly average income collected in the highest income levels from those previous quarters. Benefits would not be permitted to be lower than $125 per week, or to be greater than 85 percent of the average weekly wage in New Hampshire. Family and Medical Leave would be defined as leave from work due to the birth of a child within the past year, placement of a child with the individual for adoption or foster care, a serious health condition of the individual or a family member, or qualifying situations around foreign deployment in the Armed Forces or care for a service member with a serious injury or illness.

Many of the mechanics associated with administering this program would match those in the existing Unemployment Insurance program. Willfully making false statements or failure to report relevant facts to obtain benefits from the Family and Medical Leave Insurance Program would result in being barred from receiving any benefits for 26 weeks. Employees would be required to provide at least 30 days notice to employers before taking leave for reasonably foreseeable circumstances, and employers covered by the federal Family and Medical Leave Act are required to continue providing health insurance and restore employees to the position held prior to receiving Family and Medical Leave Insurance payments or an equivalent position.

New Hampshire Employment Security would be responsible for administering this program and continuously monitoring program solvency, with the authority to alter benefits and premiums by 10 percent from the amounts set in statute to maintain the solvency of the program as needed.

Both the Governor’s plan and the House plan would require State employees to participate. The House plan would require private employers to participate in the program or provide another form of equivalent or higher-level benefit, as certified by the State, to its employees.

The House plan would be funded by participating employers providing quarterly insurance payments equivalent to 0.5 percent of all wages paid per employee in the preceding quarter. Employers would not be allowed to withhold more than 0.5 percent of wages per week per employee to make these payments, and must supply employees with approved information regarding the program benefits. Estimates for the original House bill, which had the same funding mechanism, suggested that the quarterly payments would total $168.6 million, based on the most recent historical data available, and did not assume any local government employer participation in those calculations.

The House budget would appropriate $9.9 million to cover startup costs during the biennium, which the program would be required to refund after it began. The benefits program would be completed in 2022.

Powers for the Department of Administrative Services and Other Reorganizations

The House budget retains some of the expanded powers for the Department of Administrative Services (DAS) and reorganizations proposed in the Governor’s budget. The House budget retains the consolidation of certain state agencies and operations into the Department of Military Affairs and Veterans Services, reorganizing and codifying structures within the DAS, increasing flexibility for the Department of Corrections to move funding for personnel between budget lines, and shifting the State Commission for Human Rights under the administration of the Department of Justice. The House budget removed the proposal to consolidate oversight of visitors and welcome centers and removed the requirement that the DAS conduct a comprehensive review of the State’s personnel system.

The House budget retains the Governor’s proposal expanding the authority of the DAS over other personnel in other agencies. In an effort to effectuate consolidation or deconsolidation of human resources, payroll, and business processing functions within State government, the DAS would have the authority, with the approval of the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Governor and Executive Council, to make transfers of funds for operational purposes to the DAS from any other agency to effectuate consolidation or deconsolidation of human resources, payroll, and business processing functions within State government. The DAS may also, with approval from the Governor and Council, eliminate unnecessary positions or transfer any positions within or between the DAS or any other agency “if the commissioner of administrative services concludes that such transfers or eliminations are necessary to effectuate the efficient consolidation or deconsolidation of human resources, payroll, or business processing functions within state government.” Additionally, the DAS may establish a total number of personnel required for human resources, payroll, and business processing functions within the Executive Branch of State government.

The House also retained the Governor’s proposal to provide the DAS with the authority to not comply with the requirements under a 2016 Executive Order related to the identification and implementation of energy efficiency projects and the monitoring of energy and water use, use of fossil fuels, and greenhouse gas emissions during the biennium. Other State agencies would also be required to annually pay the DAS 50 cents per square foot of space they occupy in DAS-maintained and serviced buildings, and the DAS would not have to comply with certain Legislative Budget Assistant audits.

Other Policy Changes

If enacted as proposed, the House budget would:

- increase Civil Legal Services Aid that supports services provided by New Hampshire Legal Assistance to low-income individuals from $1.2 million per year under the current operating budget to $1.5 million per year, an increase of $850,000 per year over the Governor’s budget proposal

- provide $12.5 million during SFY 2021 in revenue sharing to cities and towns based on the sharing formula suspended since 2010[15]

- permit State aid grants for public water and wastewater infrastructure projects substantially completed by December 2018, providing nearly $2.9 million in SFY 2020 and over $2.8 million in SFY 2021

- continue to freeze Meals and Rentals Tax distribution to municipalities at current levels

- provide the Division of Travel and Tourism with 3.15 percent of the non-Education Trust Fund portion of Meals and Rentals Tax revenue, based on the prior State fiscal year

- appropriate over $2.5 million for startup and operational costs for a DHHS district office planned for Rochester

- suspend, but not repeal as the Governor proposed, the Senior Volunteer Grant Program and the Congregate Housing Services Program, and continue the suspension of reimbursements to the Foster Grandparent Program

- retain the Governor’s proposed increase in the Social Services Block Grant program’s income eligibility for adult clients each January by the percentage amount of the cost of living increase in the Social Security program

- clarify, as the Governor proposed, that those who are clinically ineligible for federal cash benefits but otherwise eligible for public assistance programs for those who are totally disabled, blind and in need, or of old age would receive those benefits under state law

- reduced grants to the Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled Program by about $3.4 million due to projected reductions in caseloads

- transfer the Job Training Program for Economic Growth from the Department of Business and Economic Affairs to New Hampshire Employment Security, with modifications that would include additional training opportunities at the University System and establishing a Training Fund

- suspend the unfilled State demographer position and the requirement that demographic analyses be included in certain fiscal notes

- reduce the number of appraisers who must be on the staff of the Board of Tax and Land Appeals to one

- require the Trailer Bill to be released by the Governor by February 15 in the first year of each biennial legislative session

Revenue Projections and Policy Changes

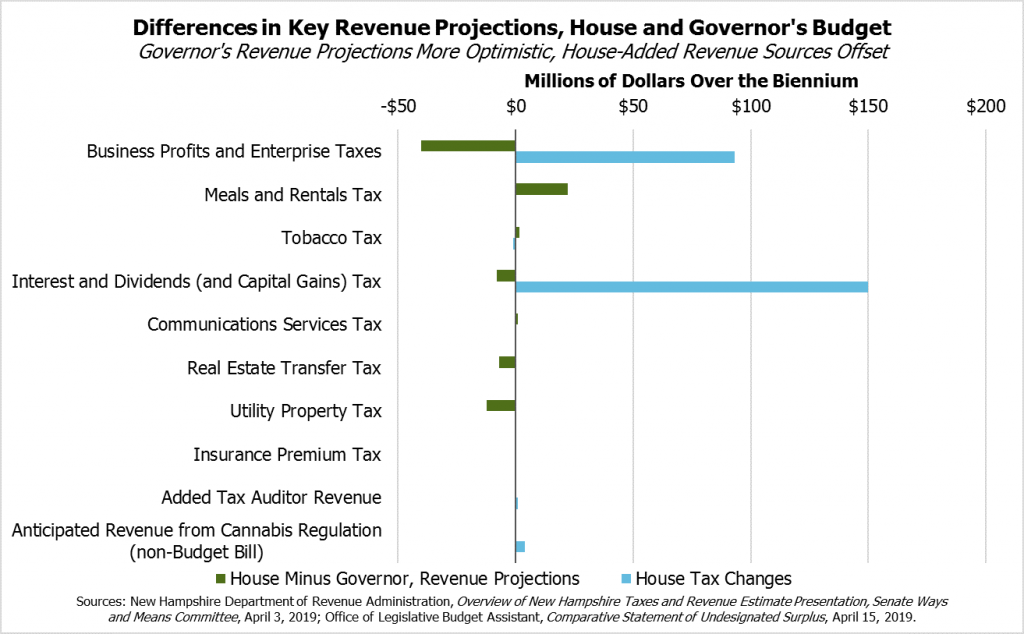

The Governor’s revenue projections were generally more optimistic than the House revenue projections. The Governor projected greater amounts of revenue from the two primary business taxes under current policy, and projected that a smaller percentage of that revenue would be the result of one-time, anomalous payments. The Governor also projected higher revenues from the Interest and Dividends Tax than the House did without policy changes, and projected higher revenues from the Real Estate Transfer Tax. The House had more optimistic Meals and Rentals Tax revenue projections.

The House budget made substantial changes to the Governor’s budget proposal relative to revenue policy. Several smaller changes were dwarfed by two larger changes.

The House replaced the Governor’s version of sports betting with its own version, which it estimates would generate $10 million in the second year of the biennium, matching the Governor’s estimate for his program. The House version would not devote ten percent of all revenue, less administrative costs, to problem gambling treatment and prevention services, as the Governor’s budget would have.

The House retained the Governor’s expansion of the Tobacco Tax to include electronic cigarettes and vaping products, although it modified the effective date to push implementation out to the second year. The Governor estimated the expansion of the tax base would add $4 million in SFY 2020 and $7.1 million in SFY 2021. The House estimated the Tobacco Tax base expansion would lead to $10 million in additional revenue in SFY 2021.

Additionally, the House planned on the regulation of cannabis, which was established in a separate House bill, to contribute $4 million in SFY 2021. The House also accounts for the costs associated with implementing cannabis legalization, totaling $2.1 million, in the SFYs 2019 and 2020 budget assumptions.[16]

No revenue collected through the Family and Medical Leave Insurance program is used to balance the House version of the budget, as the revenue collection and expenditures would be implemented through a separate, self-sustaining program similar to Unemployment Insurance and would likely not be operational during this budget biennium. Startup costs, however, are accounted for in the House version of the budget.

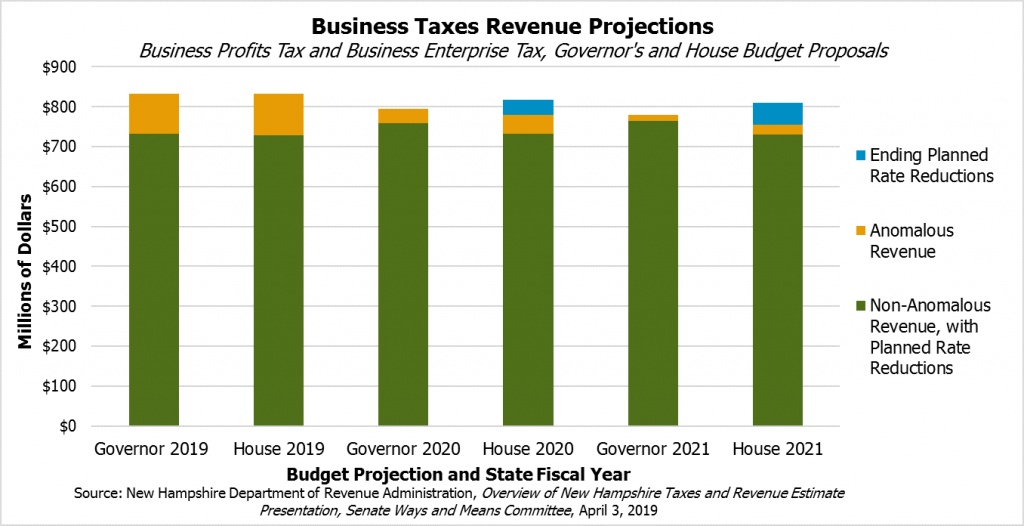

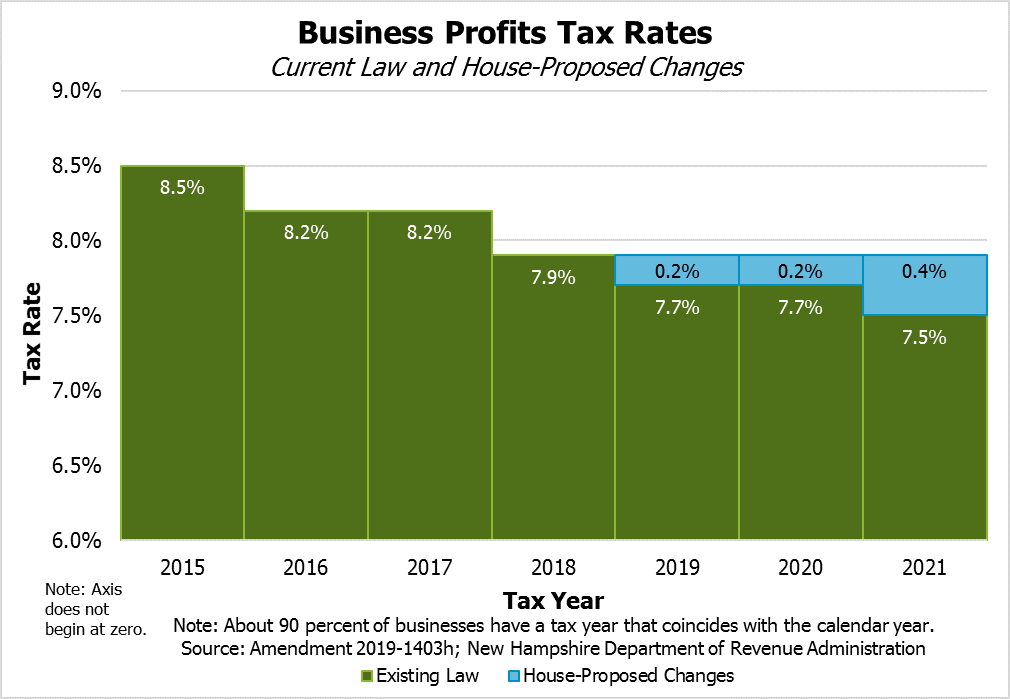

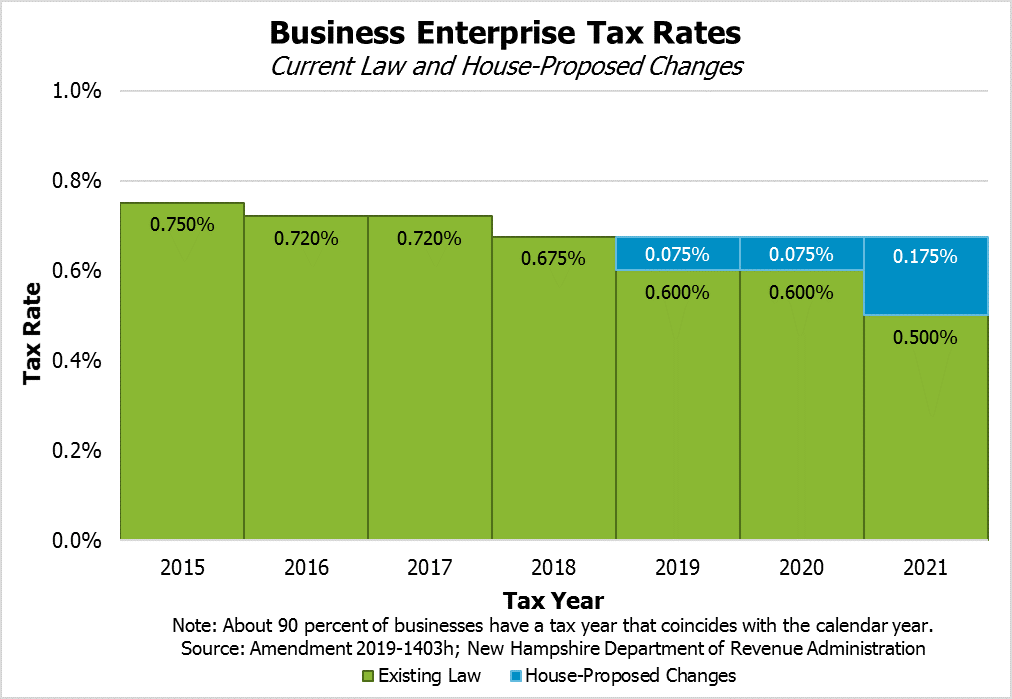

Business Tax Rates

The House made changes to planned rates for the State’s two primary business taxes, the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax, during the biennium. The Business Profits Tax is undergoing a series of rate reductions under current law, from a rate of 8.5 percent for 2015 to 7.5 percent for 2021. The Business Enterprise Tax is also undergoing rate reductions on the same schedule, falling about 33 percent from a rate of 0.75 percent in 2015 to 0.50 percent in 2021.[17]

The House proposed holding the Business Profits Tax and Business Enterprise Tax rates at 2018 levels, which are 7.9 percent and 0.675 percent, respectively. Some businesses have likely already paid quarterly estimates under the lower 2019 rates under current law, but final tax liabilities for 2019 will be paid in March or April of 2020.

The business tax rate changes proposed by the House would bring in approximately $93.1 million in additional revenue for the General and Education Trust Funds, as projected in the House budget. This would include $37.6 million in SFY 2020 and $55.5 million in SFY 2021.

Additionally, the House budget extends the Coos County Job Creation Tax Credit against the Business Enterprise Tax until 2027. It also anticipates that auditors from the Department of Revenue Administration will collect $1 million more than estimated by the Governor during the biennium.

Expansion of Interest and Dividends Tax to Include Capital Gains

The House budget adopts a proposal, passed in a separate House bill, that would expand the existing Interest and Dividends Tax to include capital gains in the tax base.[18] Capital gains result from the sale of an asset at a higher price than the purchase price amount. Capital gains from certain sales, such as stocks and bonds held as investments or most real estate sales with gains over $250,000 for an individual or $500,000 for joint filers, are taxed under federal law and would be taxed at a 5 percent rate under the House budget proposal.[19]

The House budget would also change the filing thresholds for the Interest and Dividends Tax, raising them to exempt more people from the new combined Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax. While the current filing threshold for the Interest and Dividends Tax is $2,400 for an individual, partnership, limited liability company, or association, the filing threshold would be raised to $5,000 during a tax year, with income below those thresholds exempt. Joint filers would be exempt up to $10,000, up from $4,800 under current law. The House also voted to amend the statute to increase the additional income exemption for those aged 65 years and older from $1,200 to $7,500, increase the income exemption from $1,200 to $2,500 for those who are blind, and from $1,200 to $2,500 for those under age 65 who have a disability and are unable to work.

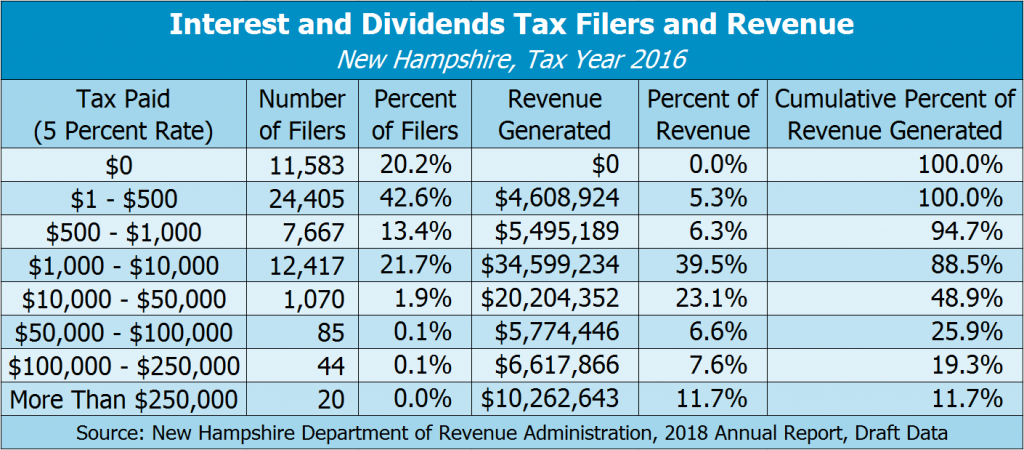

Increasing these exemptions would likely reduce State revenue collected through the traditional Interest and Dividends Tax base and would likely substantially reduce the number of individuals filing under the current Interest and Dividends Tax. About 20.2 percent of Interest and Dividends Tax filers for tax year 2016, the most recent year with published data, did not owe any tax, while another 42.6 percent of filers owed between $1 and $500. A tax liability of $500 indicates that the taxpayer had $10,000 of taxable income from interest payments, dividends, stock distributions, and other liabilities in the current Interest and Dividends Tax base. Of the revenue generated by the Interest and Dividends Tax, only 11.5 percent came from those who owed less than $10,000 in tax year 2016; this indicates those filers who had more than $200,000 in income from non-wage, non-capital gains, interest, dividend, and distribution income that was taxable under the Interest and Dividends Tax paid 88.5 percent of the revenue in tax year 2016. Increasing exemptions would likely decrease the number of taxpayers paying relatively small amounts in Interest and Dividends Tax while preserving most of the tax base, which is disproportionately comprised of high-income individuals.[20]

Although capital gains are not currently taxed in New Hampshire, national data provides information about who the capital gains tax might affect most in New Hampshire. Notably, New Hampshire does tax capital gains in limited circumstances under the Business Profits Tax. However, New Hampshire law states that income taxable under the current Interest and Dividends Tax is not taxable under the Business Profits Tax, and the House proposal would not change that exemption after the expansion of the tax base to include capital gains. This may reduce the tax rate for some taxpayers from 7.9 percent under the Business Profits Tax as proposed by the House budget to 5 percent under the Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax.[21]

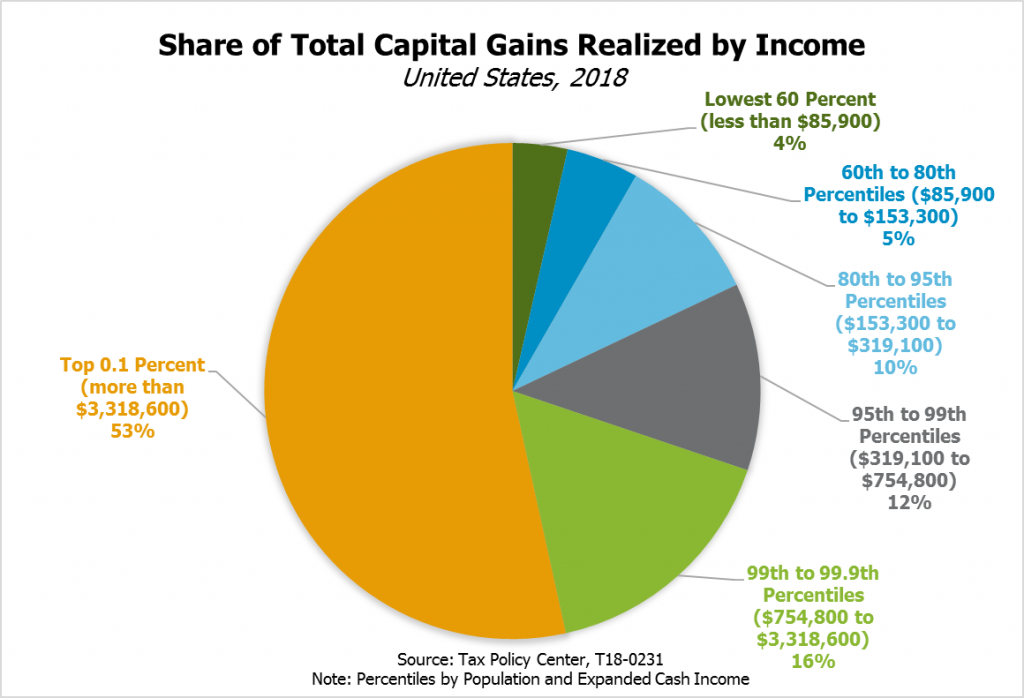

Capital gains taxes are likely to be disproportionately paid by high-income people. Using data from the United States as a whole, the Tax Policy Center estimated that about 90.2 percent of all capital gains went to the top 20 percent of income earners, which was about $153,300 per year in cash income and certain benefits, during 2018. The top one percent of income earners, or those with incomes of about $754,800 per year or more, accounted for 68.7 percent of all capital gains, and approximately 52.6 percent went to the top 0.1 percent, or those with more than $3.3186 million in income.[22]

New Hampshire’s Interest and Dividends Tax generated $105.8 million in revenue during State Fiscal Year 2018.[23] The House budget projects expanding the Interest and Dividends Tax to include capital gains would generate an additional $150 million in revenue each year. The House budget would appropriate the first $150 million generated by the Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax to the Education Trust Fund, primarily to pay for increased aid to property-poor school districts and those with more children from households with low incomes.

The Surplus and Savings Funds

The House budget would retain the Education Trust Fund and add to the Rainy Day Fund, retaining resources in these non-lapsing accounts. The Governor’s budget proposed adding more to the Rainy Day Fund than the House proposal, but also proposed eliminating the Education Trust Fund.

The House budget would not establish the Capital Infrastructure Revitalization Fund or the Targeted School Building Aid Reserve Fund; the Governor proposed both funds for use of the General and Education Trust Fund surpluses, respectively, which would have deployed these surplus funds for specific purposes. The Governor’s proposal would have expended these funds during the biennium in a one-time fashion outside of the State’s operating budget. The House budget would carry forward these surplus funds and deploy them through the State operating budget, leaning heavily on carried forward surplus funds to fund an estimated $106.5 million more in expenditures than revenues in SFY 2020. That gap between same-year revenues and expenditures narrows considerably to $31.9 million in SFY 2021, and both the General and Education Trust Funds end SFY 2021 with a balance totaling $29.7 million, based on revenue estimates in the House plan. However, additional revenues may be needed to support future services if same-year revenues and expenditures do not come into balance, as one-time tax receipts supporting the current revenue surplus are not expected to be repeated.

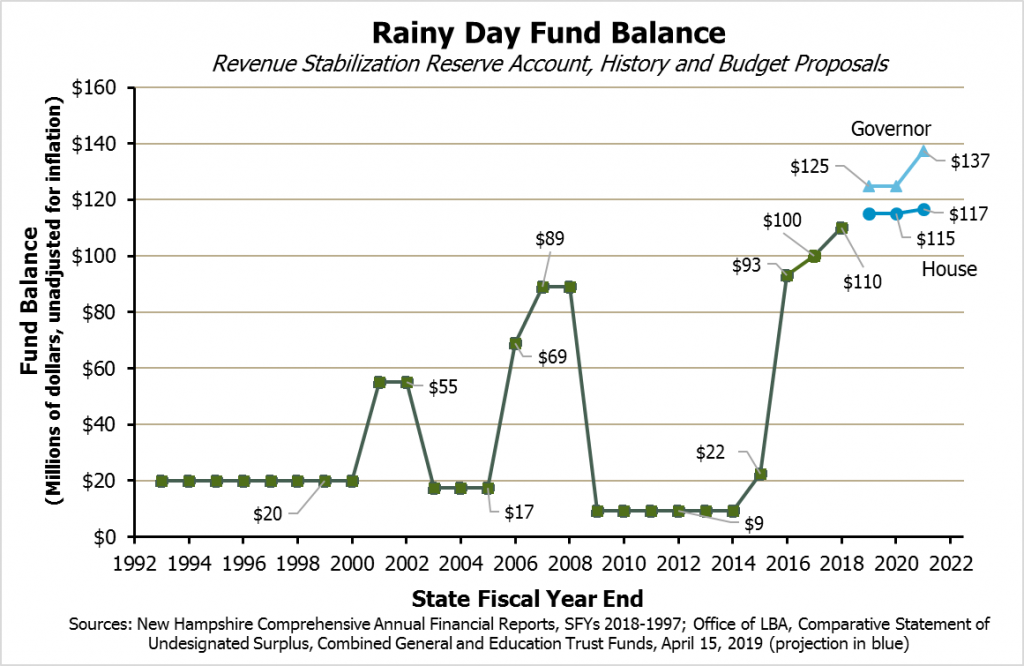

The Rainy Day Fund

The House budget would add $5 million to the Rainy Day Fund from the $173.1 million surplus projected for the end of SFY 2019.[24] This contribution would bring the total to $115 million during the biennium. The House anticipates adding about $1.7 million in surplus revenue at the end of SFY 2021. The Governor’s proposal would have added $15 million in SFY 2019 and another $12.3 million in SFY 2021, reserving most of the rest of the surplus for spending on specific projects and initiatives through the proposed Capital Infrastructure Revitalization Fund, which the House budget does not incorporate.

The Education Trust Fund

The House opted to retain the Education Trust Fund, which the Governor proposed eliminating while diverting funding sources to the General Fund and the Sweepstakes Fund. The Education Trust Fund is required to retain any surplus it carries forward, rather than allowing it to lapse to the General Fund. In most years, the Education Trust Fund runs a deficit and must be supported by a transfer from the General Fund, but surplus revenue resulting in part from one-time effects following the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act have pushed the Education Trust Fund into surplus, which it retains absent other changes in law.[25]

The House plan projects that the Education Trust Fund will retain a surplus throughout the biennium, despite the increased expenditures on Adequate Education Aid. The House budget also proposes shifting the source of funds for school building aid, tuition and transportation aid, and special education aid to the Education Trust Fund.

Concluding Discussions

The House budget would appropriate significant additional resources to support the education, health, and well-being of Granite Staters. By using the surplus for ongoing services and adding revenue, the House budget would send more aid to local governments, which could be used to reduce property taxes and support additional services. Added support for public schools would be wisely directed to districts with the most constrained fiscal capacities, as they have the most limited abilities to raise revenue for education on a per student basis. Supporting low-income students with additional aid to school districts, particularly those school districts where many students face limited means at home, increases the opportunities for those children and encourages both upward mobility for individuals and future vibrancy in areas with less economic activity. Establishing paid family and medical leave insurance would also provide added certainty for those with limited means, who may be less able to absorb the negative financial and other life impacts of an illness or misfortune for a family member. The House budget also makes limited but meaningful investments in easing housing constraints for some of the state’s most vulnerable residents.

The House proposal seeks to address both education funding and health care challenges in the State, including through making an investment to inform future education funding changes. However, the House budget relies on surplus revenue from one-time receipts to fund services during the biennium and does not completely transition the increased expenditures to new revenue sources. The House budget projects a positive balance throughout the biennium, but a decline in available one-time revenues and concerns about the economy suggest that the next biennium may be more difficult to achieve balance while maintaining these important services. Additionally, the state’s mental health and workforce challenges remain ongoing concerns. Broad increases to Medicaid reimbursement rates would likely help ensure providers are available to deliver services to those in need. While the House budget protects county taxpayers from paying for significant increases in certain parts of Medicaid, additional steps to increase reimbursement rates would likely help alleviate many of the current challenges facing Medicaid service delivery.

The House budget takes steps to address long-term challenges that have been only considered in piecemeal fashion in recently enacted budgets. No two-year budget can solve every longstanding concern around supporting services for Granite Staters, but the House budget makes significant steps toward rebalancing New Hampshire’s priorities in a manner that promotes long-term prosperity for all the state’s residents.

Next Steps

With the passage of the House budget, the deliberative process moves to the Senate Finance Committee. The Senate Finance Committee will make amendments and provide its version of the State Budget to the full Senate, which will vote as a chamber on the Finance Committee’s proposal on or before June 6. Following this vote, if the House differs from the Senate position, the two chambers must form a Committee of Conference by June 13, and that Committee must agree on a final version of the State Budget by June 20. The full House and Senate must act on the State Budget by June 27, and agree on the final version before sending the State Budget to the Governor. The current State Budget expires after June 30, 2019, and a new plan to fund State services must be in place before July 1.[26]

With the economy performing well overall and current revenues less constrained than in prior budget cycles, policymakers are exploring opportunities in the next budget to help sustain a vibrant economy and invest in Granite Staters. The State Budget is a statement of New Hampshire’s priorities, and with funds available now to make long-term investments that will pay dividends in the future, policymakers should wisely deploy public resources to help ensure widespread prosperity for all New Hampshire residents.

Endnotes

[1] Source materials related to the Governor’s State Budget proposal and the House budget proposal are available on the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s web page for the SFYs 2020-2021 budget process. These source materials are used throughout this Issue Brief.

[2] For more information on how the State Budget is organized and for discussions on the correct metrics for comparisons of the sizes of State Budgets, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief Measuring the Size of New Hampshire’s State Budget, published September 11, 2017. For more on comparisons between State Budgets and measuring baselines, see NHFPI’s February 28, 2017 Issue Brief, Governor Sununu’s Proposed Budget, specifically the section titled “A Technical Note on Comparing Budgets.” For an explanation of the New Hampshire State Budget process, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource. For more information on the currently operating State Budget, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019, published July 13, 2017. For more information on the Governor’s State Budget proposal, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal, State Fiscal Years 2020-2021, published March 29, 2019.

[3] To learn more about the Efficiency Budget process and State agency requests, see NHFPI’s November 18, 2016 Common Cents post “New Process Will Guide Formation of Next State Budget.”

[4] For more on the method for determining Adequate Education Aid currently in place, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Fiscal Issue Brief, Calculating Education Grants, Traditional Public Schools, January 2019.

[5] For a full breakdown of reported costs, see New Hampshire Department of Education, Office of School Finance, State Average Cost Per Pupil and Total Expenditures 2017-2018, December 17, 2018.

[6] To see a list of the equalized valuation per pupil and the state average, see New Hampshire Department of Education, Office of School Finance, Equalized Valuation Per Pupil 2017-2018, December 19, 2018.

[7] For more on kindergarten funding in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s November 8, 2017 Common Cents post “Elections Highlight Continuing Questions About Keno Revenue.”

[8] To see a distribution of the aid anticipated on a municipal-level basis, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Education Funding Analysis, Preliminary Estimates – For Discussion Only, 2019-1232h, March 24, 2019. The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant produced updated estimates on April 25, 2019, which changed the totals slightly; those updated totals are reflected in the text of this Issue Brief. Municipalities that generate more locally from the Statewide Education Property Tax than necessary to fulfill the State’s Adequate Education Aid commitments under law may receive less aid than the preceding year, but other municipalities would be guaranteed at least the previous year’s aid levels.

[9] To see the total estimated distribution of new Adequate Education Aid, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Education Funding Analysis, Preliminary Estimates – For Discussion Only, 2019-1232h, March 24, 2019. The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant produced updated estimates on April 25, 2019, which changed the totals slightly; those updated totals are reflected in the text of this Issue Brief.

[10] For more information on Medicaid reimbursement rates and the Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver Program, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Care Service Delivery Limited by Workforce Challenges.

[11] Information provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, including in the document “TANF Information, DHHS 3/22/2019.”

[12] For more on the Affordable Housing Fund, see the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority Financing Programs web page.

[13] The New Hampshire Constitution limits the use of certain motor vehicle-related revenues, such as the gasoline tax, in Part 2, Article 6-a.

[14] To see the text, amendments, and progression of the bill that the House used as a basis for its Family and Medical Leave Insurance proposal, see the docket for House Bill 712.

[15] To see estimates of the anticipated amounts to be provided to each municipality, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Estimate of Revenue Sharing (HB 2, House Finance), April 9, 2019.

[16] To see the cannabis legalization and regulation bill passed by the House, see the docket for House Bill 481.

[17] The specific language in the statute surrounding the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax defines the tax rates based on tax years ending on or after December 31 of a given year. About 90 percent of businesses have tax years that coincide with the calendar year. As such, this Issue Brief refers to calendar years and tax years as equivalent, although some businesses may have a delayed change in tax rates relative to others if those businesses have a tax year based on a fiscal year rather than a calendar year. For more on the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource. For more on the implications of the business tax rate reductions, see NHFPI’s May 30, 2017 Common Cents post “Proposed Business Enterprise Tax Changes Would Eliminate General Fund Contribution.”

[18] For more on the current Interest and Dividends Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[19] For more information on how taxable capital gains are defined in federal law, see the Internal Revenue Service web pages on capital gains and losses (Topic Number 409) and the Sale of Residence – Real Estate Tax Tips.

[20] For more information on the Interest and Dividends Tax and the data source for these calculations, see the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, 2018 Annual Report, page 52.

[21] See RSA 77-A:4, I for the statute exempting income taxable under RSA 77. See also the fiscal note for House Bill 686 of the 2019 Legislative Session and Elizabeth McNichol, State Taxes on Capital Gains, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2018.

[22] For the data table, see the Tax Policy Center, T18-0231 – Distribution of Long-Term Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2018. Learn the income sources included in expanded cash income at the Tax Policy Center’s web page: Income Measure Used in Distributional Analyses by the Tax Policy Center. Learn more about the federal capital gains tax and the incomes of those historically most likely to realize capital gains from Thomas L. Hungerford, The Economic Effects of Capital Gains Taxation, Congressional Research Service, June 18, 2010.

[23] For details on revenue source collections to the General Fund by State fiscal year, see the Department of Administrative Services, State of New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018, page 148.

[24] The Rainy Day Fund is formally known as the Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account and is part of the General Fund. For more on the Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account, see NHFPI’s December 28, 2016 Common Cents post “Sun Shining on the Rainy Day Fund.”

[25] For the requirement that the Education Trust Fund be non-lapsing, see RSA 198:39. To see a recent history of Education Trust Fund deficits, see the Department of Administrative Services, New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018, page 150.

[26] See the Senate calendar for information about upcoming legislative deadlines.