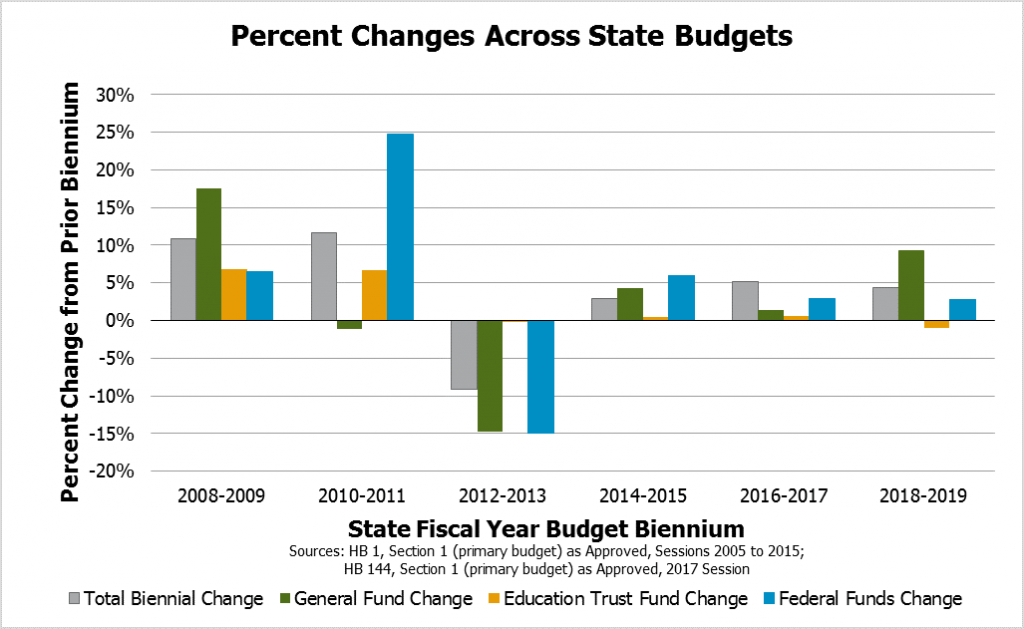

Legislative deliberations during the creation of New Hampshire’s biennial State Budget often evaluate the size of budget proposals relative to the prior biennial operating budget. Debates frequently focus on the overall growth of the budget, but measurements of different subsets of the budget or comparisons relative to different baselines can create confusion and misunderstandings.

Budget growth discussions during the 2017 Legislative Session included estimates ranging from 1.4 percent in the first year and 1.1 percent in the second year to a total increase of 10.5 percent. Numbers used in public debates and widely reported in the press characterizing the size of the final budget ranged from $11.7 billion to more than $12 billion. NHFPI’s own resources identified the final growth of the budget as 4.4 percent relative to the previously enacted State Budget, and identified the size of the budget as $11.855 billion.[1]

Throughout the budget process, there are frequently comparisons made between the various budget proposals from the Governor, the House, and the Senate, as well as the House and Senate Finance Committees and the final Committee of Conference proposals. Considerable debate in the 2017 Legislative Session focused on the amount that the Senate and Committee of Conference reduced the size of the budget relative to the House Finance Committee’s budget, while both the Senate’s and the Committee of Conference’s operating budget bills were actually larger in approved appropriations, a commonly-used benchmark, than the House Finance Committee’s operating budget bill. These discrepancies would be an interesting oddity and pale in importance relative to discussions of the services funded through the State Budget, but some legislators identified the growth and size of the budget as key to their decisions to support or oppose its passage. As such, identifying and explaining these discrepancies in measurements have important public policy ramifications.

This Issue Brief reviews the sizes of iterations of the State fiscal years (SFY) 2018-2019 State Budget and the different measurements used in the deliberative process during the 2017 Legislative Session. For a primer on New Hampshire’s State Budget process, please read NHFPI’s Building the Budget explanatory resource.[2]

The Bottom Line of the Budget

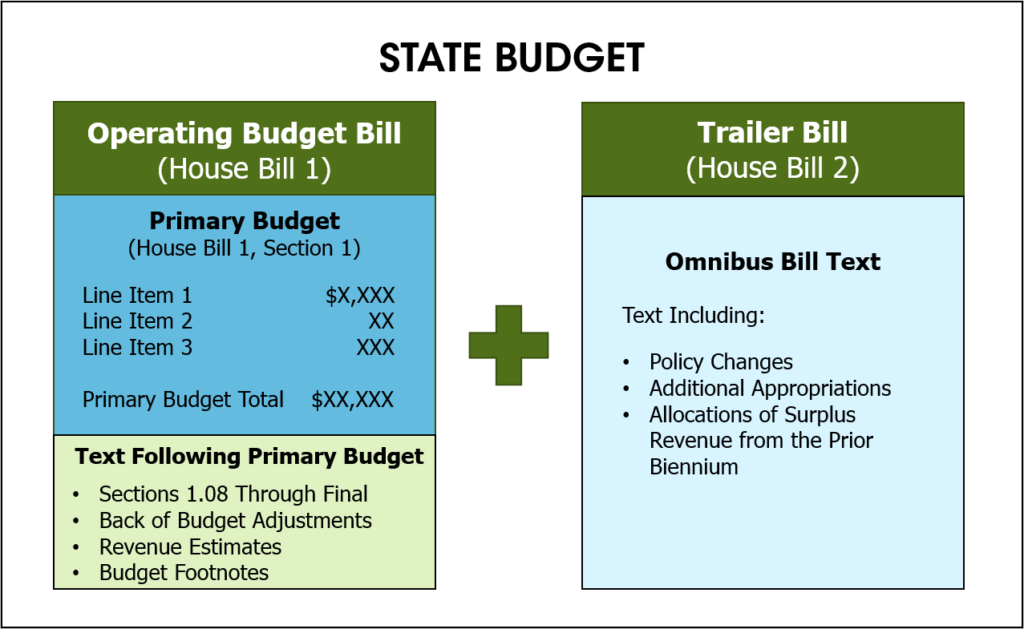

The State Budget is comprised of two bills, typically House Bill 1, which is the formal budget bill per the New Hampshire State Constitution’s requirements and is the operating budget bill, and a bill usually identified as House Bill 2. The “trailer bill,” typically House Bill 2, is an omnibus bill that provides the policy framework for certain alterations in budgeted expenditures and may also include other appropriations, as any bill may, outside of the State Budget’s operating budget bill. The primary budget, housed in the operating budget bill and often referenced as Section 1 of House Bill 1, provides a summary total of all budgeted expenditures, sourced from all budgeted funds, listed for each of the two budget years following the budget line items; the summary is usually in Section 1.07. The sum of these two budget year totals is commonly used to describe the size of the State Budget, which is $11.855 billion for the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget.[3]

During the 2017 Legislative Session, House Bill 1 and House Bill 2 did not pass the House of Representatives, preventing the two bills from advancing on to the Senate. Some Representatives identified their rationales for not voting for the budget produced by the House Finance Committee as related to the growth in the budget’s size and the removal of federal funds that were likely to be accepted and spent outside of the budget. To move the process forward, the Senate amended two other House bills, which had already passed, with the Governor’s proposed versions of the operating budget bill and the trailer bill; as such, House Bill 144 became the operating budget bill, and House Bill 517 became the trailer bill.

Tallying Up the Trailer Bill

Appropriations may be included in the trailer bill independently of the operating budget bill. For example, in the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget deliberations, the trailer bill appropriated $700,000 in SFY 2018 and $250,000 in SFY 2019 that were not in the operating budget bill.[4] Although the trailer bill is typically considered part of the State Budget, formally it is simply another bill that legislators opt to move through the process with the operating budget bill, as it only exists separately because of specific requirements in the State Constitution that apply to the budget bill. The State Constitution requires that budget bills only include the operating and capital expenses for the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and that no section or footnote contain provisions that establish, amend, or repeal statutory law other than those for government operating or capital expenses.[5] To make policy changes associated with budgetary changes, such as proposals for new programs funded through the primary budget, the Legislature typically includes those enabling changes in the trailer bill and moves it through the process with the operating budget bill. As such, trailer bill expenditures are not always considered in budget totals, as other bills can authorize expenditures out of the State Budget process as well. However, appropriations in the trailer bill are included in certain other budget-related calculations, although a separate fiscal note is not typically written for all the trailer bill’s expenditures combined. Movements of surplus dollars from the prior SFY, such as the 2017 Legislative Session’s trailer bill’s appropriation of $5.0 million in surplus General Fund dollars from SFY 2017 to support the Governor’s Scholarship Program in SFY 2018, are also not consistently included in discussions of the total budget size.[6]

The Back of the Budget

Other changes to the appropriations made in the two budget bills may come through adjustments following the first section of the operating budget bill, which contains the primary budget. The operating budget bill includes the primary budget in its first section, which holds the vast majority of the bill’s content, but also has subsequent sections in the “back” of the budget that may contain appropriations-related language and revenue projections. These back of budget adjustments following the first section, usually reductions sometimes known as “back-of-the-budget cuts,” are not included in every budget and usually include reductions to multiple lines, requiring an agency to find a particular amount of savings relative to the amount the primary budget appropriated to that agency. The House Finance Committee’s budget was the only operating budget bill proposed in the 2017 Legislative Session to include the back of budget adjustments; the Committee’s operating budget bill included an approximately $2.4 million reduction in funding to the Judicial Branch for the biennium relative to, but not specified in, the total provided in the primary budget, and a nearly $2.6 million reduction to the Department of Corrections total General Fund appropriations, without specifying individual budget lines, during the biennium relative to the primary budget appropriations. Back of budget adjustments may be included in discussions of the size of the State Budget, as they are codified into State law when passed and are in the operating budget bill, even though they are not in the primary budget.

Focusing on the Funds

The State Budget is divided into funds. These funds serve as repositories for collected revenue and for legislators to draw from to pay for State expenses.[7] These funds may have dedicated revenue sources and certain requirements or limitations as to how money from the funds may be spent. Funds may have limitations and restrictions on their uses stemming from State statute, federal grant or statutory requirements, or the State Constitution. For example, the Turnpike System Fund is financed through tolls and related payments for certain limited access highways, as well as federal grants and other sources, and appropriations sourced from this Fund must be used for constructing, reconstructing, operating, and maintaining the 89 miles of Turnpike highways.[8]

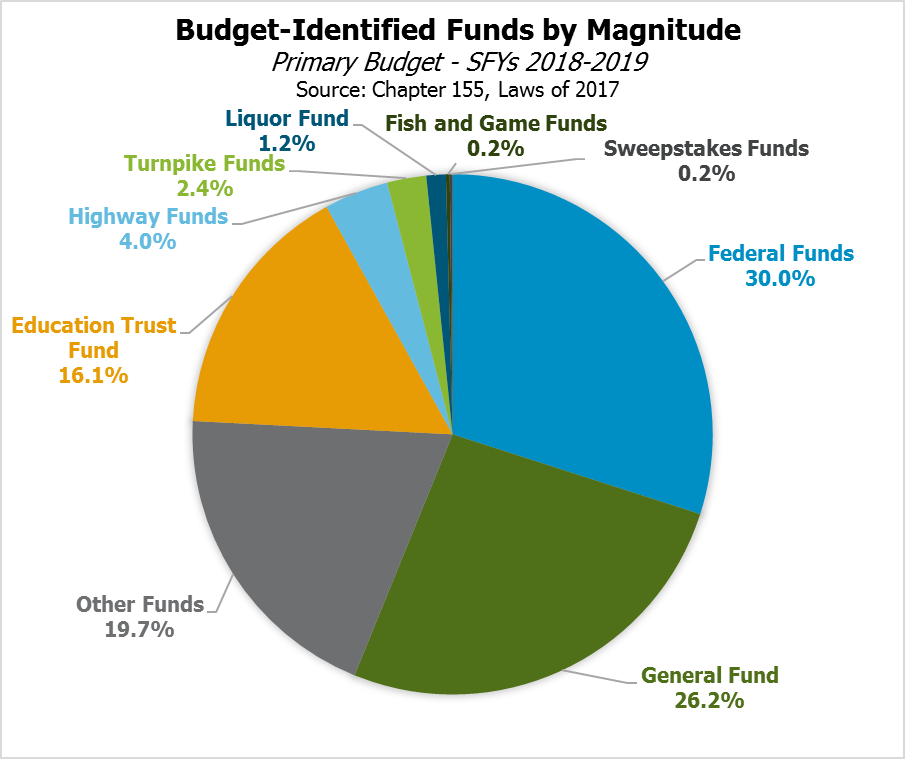

The General Fund, which constitutes approximately 26.2 percent of the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget, is the State’s least restricted fund. The Legislature has the most flexibility, relative to the other funds, to appropriate or reallocate revenue collected in the General Fund to its priorities and preferences each budget cycle. Typically, debates surrounding State Budget choices revolve around General Fund appropriations. Almost all General Fund revenue stems directly from State tax collections, fines and fees, and liquor sales.[9]

The Education Trust Fund, which comprises approximately 16.1 percent of the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget, is also primarily funded through State sources, including taxation, lottery revenues, and transfers from the General Fund. The Education Trust Fund was established to deposit and distribute money for Adequate Education Grants for municipalities to fund education for their pupils. This Fund also supports the Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief program, which provides partial rebates for Statewide Education Property Tax payments to certain low-income people who meet the program’s eligibility requirements. Most years, the revenue streams assigned to support the Education Trust Fund do not adequately cover the costs, so additional General Fund dollars are appropriated to be transferred to the Education Trust Fund; excess Education Trust Fund dollars have been transferred to the General Fund twice between SFYs 2007 and 2016, although there is no automatic provision for a transfer in this direction in statute.[10]

Due to the flexibility afforded legislators in General Fund allocations and its reliance on State tax revenue sources (rather than federal programs, agency fees, or other revenue sources[11] that support the State Budget), some observers opt to focus on the General Fund’s total appropriations when discussing the budget’s size. General Fund dollars are often matched with Federal Funds for certain federal grant programs, meaning General Fund appropriation choices may have a multiplied impact on the overall size of the entire State Budget. The General Fund is also more likely to grow or shrink with changes in State tax receipts, often due to changes in the economy.

As the General and Education Trust Funds are the repositories for most traditional State taxation (with some key exceptions, such as the Motor Fuels Tax), some observers focus on the changes in these two funds put together.[12] Given that these two funds also interact frequently through transfers from one to the other, measuring them together provides a more complete picture of the magnitude of expenditures funded through unrestricted State taxation and other, less restricted revenue sources. However, the Education Trust Fund’s dedicated purposes means the fluctuations in obligated expenses tend to be smaller, particularly in recent years as student populations have stabilized and begun to decline, than some recent General Fund changes. When measuring a percentage change in the size of the appropriations, adding the Education Trust Fund to calculations of General Fund changes is likely to make the percentage changes smaller, unless there is a major shift in expected student populations, relative to the General Fund.

The General and Education Trust Funds are also measured together in the most commonly referenced Surplus Statements generated by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant (LBA). These Surplus Statements can show the changes in General Fund appropriation decisions across iterations of the State Budget as well as any expected transfers to the Education Trust Fund from the General Fund. These documents, and estimates of revenue collections used by both the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees, facilitate the use of the General and Education Trust Funds together as a method of measuring the size of budget appropriations. Notably, the LBA generates Surplus Statements for the General and Education Trust Funds individually and separate Surplus Statements for the Highway Fund and the Fish and Game Fund; the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees also generate separate revenue estimates for the Highway and Fish and Game Funds.[13]

While examining the General Fund, or the General and Education Trust Funds together, is informative and provides certain insights, looking at only these funds omits about 57.7 percent of the primary budget, which includes vast swaths of State operations under the purview of legislators voting on the biennial operating budget. Additionally, legislators can move certain revenue streams or expenditures inside or outside of General Fund or Education Trust Fund expenditures through State law, changing the size of these funds without altering the scope of, and revenues necessary for, State operations.[14] Describing changes in the size of the State Budget in terms of just the General Fund, or the General and Education Trust Funds, should be done with specificity and in conjunction with discussions of changes in the overall size of the State Budget.

Looking at the Lapses

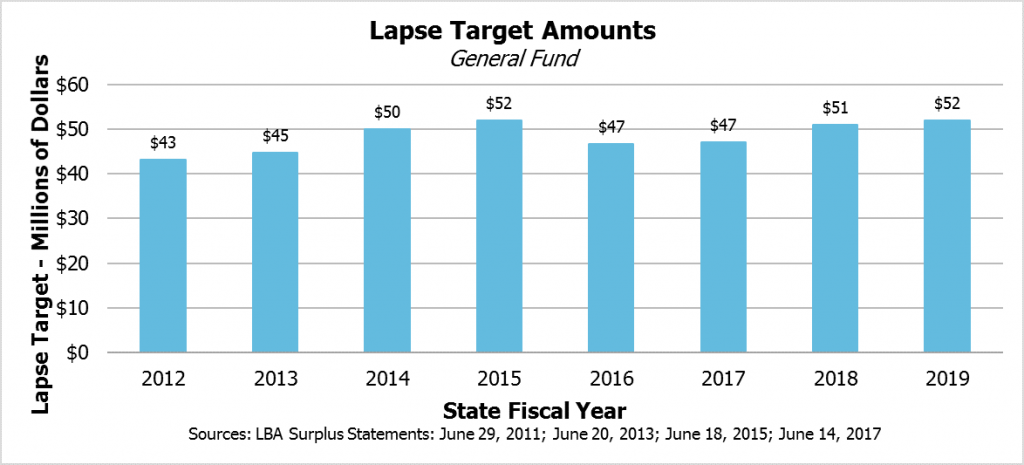

The lapse target, often called “the lapse,” is designed to encourage State agencies to find efficiencies within every appropriation by requiring a certain percentage reduction in spending relative to the actual appropriations agencies are assigned in the State Budget. The lapse does not specify where these reductions relative to appropriations must be made. Essentially, the Legislature expects the Governor to find savings in the State Budget for the budget to balance. These lapses are also sometimes referred to as “back-of-the-budget cuts,” which is a term also used to describe changes in the operating budget bill outside of the primary budget itself, as noted previously. (In this Issue Brief, references to back of budget adjustments are referencing components of the operating budget bill outside of the primary budget, not lapses.) Targeted lapses are calculated for the General, Education Trust, Highway, and Fish and Game Funds and included on the LBA Surplus Statements. However, these lapses are not required by statute, nor are they explicitly stated in the State Budget documents themselves; they only serve as an assumption designed to balance the budget and encourage efficiencies in State agencies. If a lapse target is not met, either surplus revenue allocations or additional adjustments must be made to pay for State expenses.[15]

Some legislators opt to include the lapse target when discussing the size of the budget. Lapse target calculations, however, are limited to the four funds with LBA Surplus Statements; lapses that could occur in other accounts or funds are not estimated. As such, this lapse estimate is rendered somewhat incomplete for use relative to the entire State Budget. Agencies are not required to meet the lapse targets by statute. The House and Senate do not vote on the lapse when they vote on the State Budget, as it is only a target assumption.

Fiddling with the Federal Funds

Legislators can opt to appropriate funds through separate legislation outside of the State Budget, either through distinct bills or through the authority granted to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. The Fiscal Committee is tasked with managing the State Budget on a regular basis and, in conjunction with the Governor and the Executive Council, may make additional appropriations and accept certain funds not included in the State Budget. For example, during SFYs 2016-2017, the Fiscal Committee approved more than $640 million in additional funds, much of which was transferred from external sources but not included in the State Budget.[16] The Fiscal Committee’s authority to make these changes means the Legislature can opt to remove funds, particularly federal grant money, from the State Budget with the expectation those funds could be accepted through the Fiscal Committee at a later date.[17]

During the 2017 Legislative Session, both the House Finance Committee and the Senate Finance Committee removed funds that could be accepted through other authorities. The two primary methods used were moving certain federal funds through the Fiscal Committee, Governor, and Executive Council, and by using the authority in existing statute to appropriate certain money to purchase vaccines. In total, the House Finance Committee opted to move nearly $219.1 million in federal and other funds proposed by the Governor for the biennium out of the operating budget bill using these two methods. The Senate moved almost $237.8 million in appropriations out of the Governor’s proposal with the expectation some or all the funding would be authorized through these alternative methods during the biennium; the Senate’s removals matched those in the final budget as approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor.[18] For example, the federal matching funds to support the Medicaid to Schools program were removed, reducing the primary budget’s top line appropriations by just under $70.1 million for the biennium. During the August 25, 2017, Fiscal Committee meeting, the first meeting after the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget was signed into law, the Committee voted to accept nearly $70.1 million in federal funds to support the Medicaid to Schools program for the biennium.[19]

Sifting Through the Summations

The relative sizes of different iterations of the State Budget created during the 2017 Legislative Session depend greatly on the metric used to evaluate the State Budget’s size. The Governor’s budget proposal was the largest by each metric discussed in this Issue Brief except for size comparisons of the General Fund only. The smallest budget is the House Finance Committee’s budget proposal unless the trailer bill expenditures or lapses are included; the House Finance Committee’s trailer bill included $50 million in appropriations to municipalities that were not included in its operating budget bill, and the Senate and Committee of Conference both had larger lapse target reductions relative to the budget’s appropriations than the House Finance Committee.

The differences in the bottom lines between the four primary budget proposals show a substantial drop between the Governor’s proposal and the other three, but a relatively small difference between the three proposals from legislative bodies. This difference grows wider using other measures, primarily due to the House Finance Committee’s inclusion of large appropriations in the trailer bill. Legislators interested in the changes in appropriations associated with both bills in the State Budget should consider the operating budget bill, including back of budget adjustments, and the appropriations made independently in the trailer bill. Lapses are not included in statute, and while the totals including the lapses have been used as points of comparison in the past, legislators should recognize that the lapses are not included in the actual text of the bills they vote on when they are considering the State Budget.

Considering just the General Fund or the General and Education Trust Funds together, the House Finance Committee’s budget was consistently the smallest, while the Senate’s General Fund allocation was largest. The Governor’s budget was the largest when the Education Trust Fund is included in the comparisons, in part due to the Governor’s proposed full-day kindergarten subsidy program and reductions in school enrollment projections following the Governor’s proposal.

The confusion associated with the different measurements for the State Budget’s size used during the 2017 Legislative Session are reflected in the widely reported totals. Neither the ordering by size nor the magnitude of the differences in the widely reported totals reflect the primary budgets; the House Finance Committee primary budget was the smallest of the four, rather than the second-largest, and all three primary budgets produced by the Legislature only varied within a $5.9 million range, rather than the approximately $200 million drop reflected in the widely reported totals. Including all statutory appropriations associated with the two State Budget bills matches the size-ranked order of the widely reported totals, but using this metric all three bills crafted by the Legislature would have rounded to $11.9 billion. None of the metrics explored in this Issue Brief result in the final State Budget rounding to $11.7 billion where at least one of the other budgets does not also round to $11.7 billion; by no explored metric does the Senate budget round to $11.8 billion. The widely reported totals likely show these inconsistencies due to different metrics being used to describe the size of the State Budget during the course of the process.

Sizing Up the Sizes

Each of the measures presented in this Issue Brief has a valid purpose, but some measures are more helpful than others for understanding the size and impact of the State Budget. While policymakers and observers may focus on the General Fund, which holds dollars that legislators can appropriate with the greatest flexibility, excluding the other funds omits major State operations and revenue sources, such as the Motor Fuels Tax, the Medicaid Enhancement Tax, federal funding, and many program fees. Expanding the scope to the Education Trust Fund provides a greater portion of the overall budget picture and captures more of the scope of less restricted State revenue collections, but does not represent even half of the expenditures directly authorized through the State Budget.

The primary budget includes most appropriations, and usually provides the best indication in a single line as to the size of the State Budget; this makes the bottom line of the primary budget the best comparable benchmark, especially when considering the totals of individual funds. However, the back of budget adjustments in the operating budget bill and the appropriations in the trailer bill are changes to appropriations made in the budget process, even if they are described in text and not included in the line items of the primary budget. Lapses are not State law, and the assumption that lapse targets will be met should be explicitly stated when including lapses in budget size comparisons.

Recommendations for Readers

When examining the size of the budget, legislators and other observers should:

- Look at the bottom line in the primary budget, typically at the bottom of House Bill 1, Section 1, specifically in Section 1.07. This is where the vast majority of expenditures included in law are commonly listed and added together. For the primary budget to be a complete reflection of all appropriations made by the State Budget, this total would be the sum of all expenditures authorized in the budget.

- Examine the sections following the primary budget in the operating budget bill. These sections may include other changes to appropriations, usually including those that cut across budget lines in the primary budget within a single agency.

- Identify changes in appropriations in the trailer bill that are not included in the operating budget bill. Some appropriations are discussed in duplicate, and some are appropriations of the prior State fiscal year’s surplus funds. Changes to appropriations in the trailer bill that are not reflected in the primary budget may be worthy of further examination, as the two bills move through the State Budget process together, and including appropriations in the trailer bill, rather than the primary budget, may make additional expenditures unnecessarily difficult to isolate and measure. Unfortunately, the trailer bill does not usually include a total aggregate cost in its text or in a fiscal note, but the LBA often provides information regarding the appropriations in the trailer bill in the Surplus Statements and other supporting documents.

- Determine lapse targets using the LBA Surplus Statements. Recognize, however, that these lapse targets are assumptions about State expenditures and not included in law. These lapses provide an indication of the amount of pressure State agencies may feel to spend less than they are appropriated in the State Budget.

- Evaluate the extent to which funds authorized in different versions of the State Budget were shifted to be authorized through the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee or other mechanisms. If funds were shifted, there may be a policy rationale for piecemeal authorization, or such shifting may have been done for other reasons.

- Track the use of any remaining surplus dollars from the prior fiscal year. These funds may support operations funded through the primary budget and appear in the total, or they may be appropriated in a manner which reduces the size of the primary budget.

- Ensure, when discussing the size of the State Budget, use of the same baseline throughout the process. Opting to include some components, such as lapses or trailer bill expenditures, during some parts of the process and not others can create confusion.

Legislators crafting the State Budget should seek to include all relevant appropriations in the primary budget. Doing so yields a more transparent budget document and eases comparisons with historical budgets. Shifting funds out of the primary budget with the understanding the same amount of funds will be authorized by the Fiscal Committee at a later date may make the appropriation process more difficult for citizens to understand. Legislators should also consistently treat surplus dollars allocated from the prior fiscal year in a manner that clearly conveys the funding of State operations during the budget biennium. If legislators incorporated all funding allocations in the primary budget where applicable and elsewhere in the State Budget where appropriate, including for key programs not included in the current State Budget, discussions surrounding the State Budget’s size would be more transparent.

Endnotes

[1] For a review of the final SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget as passed, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019.

[2] For reviews of individual iterations of the State Budget during the 2017 Legislative Session, see NHFPI’s Issue Briefs on Governor Sununu’s Proposed Budget and The State Senate’s Proposed Budget; see also NHFPI’s Common Cents blog posts on the House Finance Committee’s budget and the Committee of Conference’s final changes. For more on the steps in the process of creating the State Budget, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource. To view all of NHFPI’s work related to the State Budget deliberations of the 2017 Legislative Session, see NHFPI’s NH State Budget web page.

[3] For more on the two bills that comprise the State Budget, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource, page 6.

[4] To see the breakdown of these appropriations, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Surplus Snapshot from June 14, 2017.

[5] For the full text of the requirements, see the New Hampshire State Constitution, Part Second, Article 18-a.

[6] Using SFY 2017 surplus dollars to fund the Governor’s Scholarship Program in SFY 2018 drew from available SFY 2017 surplus, which limited the amount of surplus dollars available for other expenditures. However, because the trailer bill appropriated the $5.0 million from SFY 2017, the appropriation did not have to be written into the SFY 2018 primary budget for authorization, and the final value of the SFYs 2018-2019 budget did not have to be increased accordingly, as this appropriation was sourced outside of the budget. The LBA’s Surplus Snapshot from June 14, 2017, shows the movement of these funds, but the appropriation was made through the trailer bill, Chapter 156:109, Laws of 2017, and the Governor’s Scholarship Program is appropriated zero dollars in SFY 2018 under the primary budget, Chapter 155, Laws of 2017, page 15. In contrast, the $13.9 million in funds moved from the General Fund SFY 2017 surplus to the Highway Fund to support SFYs 2018-2019 operations appear in the primary budget as sourced from the Highway Fund.

[7] For more information related to State revenue sources, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[8] For more on the funds in the State Budget, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource, pages 11 through 13. For more on the Turnpike System Fund, see the LBA’s Department of Transportation, Fleet Management Performance Audit, November 2014, page 6.

[9] To learn more about the State’s methods of collecting revenue and the destinations of State revenue streams, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource. For more details on the General Fund’s revenue sources, see the State of New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2016, page 134.

[10] To see more details on the recent financing of the Education Trust Fund, see the State of New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2016, page 136.

[11] See NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource to learn more about State revenue sources.

[12] For more on State revenue sources and destinations, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource. The General Fund is often the repository for State revenue used to provide the State match for federal programs, which brings in more federal revenue and has a magnified impact on the size of the budget. The Education Trust Fund received federal funding support for the SFYs 2010-2011 State Budget; see Chapter 143, Laws of 2009, page 923 and the LBA’s Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus, Senate Passed, June 4, 2009, page 6.

[13] To see the LBA Surplus Statements generated during the 2017 Legislative Session for the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget deliberations, see the LBA’s FY 2018-2019 Operating and Capital Budget web page.

[14] Changes to statute associated with the Medicaid Enhancement Tax provide a recent example of revenue streams moving away from the General Fund due to changes in statute. See the State of New Hampshire Information Statement, March 24, 2017, page 21.

[15] The term lapse also describes unspent money in an account transferred elsewhere when the end of that account’s authorization to hold and spend that sum of money ends. To learn more about the lapse, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource, page 15.

[16] To see the individual revenues accepted and expenditures authorized by the Fiscal Committee during the SFYs 2016-2017 biennium, see the LBA’s Additional Revenues and Positions – Biennium Ending June 30, 2017, June 16, 2017.

[17] For more information on the Fiscal Committee and expenditures outside of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource, pages 6 and 7.

[18] To see the individual items removed by the House Finance Committee from the primary budget to be appropriated through alternative methods, see the House Finance Committee’s HB 1 Section 1 Amendment, Appropriation Reductions, March 27, 2017 (5PM Revised); see also NHFPI’s Common Cents blog post on the House Finance Committee’s budget proposal. To see items removed by the Senate to be appropriated by alternative methods, see the LBA’s Detail Change report comparing the Senate-passed budget to the Governor’s recommendations from June 1, 2017; NHFPI’s Issue Brief on the State Senate’s Proposed Budget includes the total figure. The authorization for vaccine appropriations is in RSA 141-C:17-a. To learn more about the State Budget as passed, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief on The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019.

[19] See Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee agenda item FIS 17-117. To learn about the Medicaid to Schools program, see NHFPI’s Common Cents blog post on Medicaid to Schools.