The COVID-19 crisis presents an extraordinary challenge for the Granite State. Necessary efforts to protect public health and slow the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus have dramatically altered daily life in New Hampshire and across the country. This is both a health and an economic crisis, and the negative effects are greatest on many of New Hampshire’s most vulnerable residents. Rapid declines in economic activity have led to an unprecedented rise in unemployment and threatened the financial security of tens of thousands of Granite Staters. While the economic damage is vast, continued measures to slow the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus are in the best interest of residents and the economy in the long term.

Many of those disadvantaged in the decade since the last recession have only recently seen their purchasing power return to pre-recession levels. The COVID-19 crisis is disproportionality affecting many of these Granite Staters. Available data indicate the number of unemployed people in the state may have quadrupled in just two weeks. Many workers previously employed in the accommodation, food service, or retail sectors, which have been dramatically impacted by measures to slow the spread of the virus, were earning wages considerably lower than statewide averages, and likely have very limited savings. Individuals and families who were already struggling to make ends meet financially are among those most economically exposed to this crisis.

New Hampshire has an older demographic than the country as a whole, and older adults may be at greater risk of suffering from more serious COVID-19 symptoms.[i] Additionally, those who require regular access to health services, including those with mental health or substance misuse treatment needs or who have a disability, may have their services curtailed or needs exacerbated by the effects of this crisis. The stress and anxiety caused by the COVID-19 crisis may affect the mental and emotional well-being of residents of all ages, including children.[ii] The efforts of health care, human service, and emergency response workers, who often already faced funding limitations and other challenges to meeting the needs of New Hampshire’s population, will be essential in the weeks and months to come.

Recent policy actions that help ensure access to housing and health coverage, assist individuals and families with children to obtain food, and expand supports for those who have lost employment will be essential through the crisis and beyond. Additional protections allowing the delay of required payments for rent, taxes, and utilities also will help residents stretch limited incomes further. More assistance will likely be needed in all these areas, particularly if the crisis persists for an extended period.

Federal and State policymakers have already taken key steps to provide relief, but both additional short-term policy responses and long-term investments will be needed, as the negative effects from this crisis may be extensive. New Hampshire’s revenue streams are likely to be severely impacted in the short term, and may not recover fully for the duration of this State Budget biennium. Recent research suggests New Hampshire was less well-prepared for a recession than most other states. While federal aid will provide critical support, the State will likely need to raise additional resources to both offset budget shortfalls and make the longer-term investments that will help to bolster economic resiliency.

This Issue Brief reviews some of the key challenges the COVID-19 crisis presents in New Hampshire, with a focus on both the economic impacts to individuals and the fiscal impacts on the State government. The Issue Brief also outlines relevant policy steps already taken at the federal and state levels, and potential policy options to help lay the foundation for an economic recovery that lifts all Granite Staters.

Initial Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis

Responses to combat the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus have resulted in drastic changes to the ways Granite Staters live and work. Minimizing interactions between individuals and limiting travel outside of home except for essentials are required to reduce community transmission of the virus. This need to distance from each other has prompted the contraction of many industries that cannot easily adjust to a work model that minimizes physical interaction and has put strain on some industries that provide essential services. Subsequent potential effects on the overall economy have been estimated, and while exact impacts are still hard to predict, an economic recession seems imminent.[iii],[iv] While the long-term economic implications of the COVID-19 crisis are uncertain, what is known is that the decline in economic activity has been sudden and steep, and many Granite Staters may face considerable detrimental effects to their own economic security and well-being.

Pandemic Places Many Workers at Risk of Unemployment or Exposure

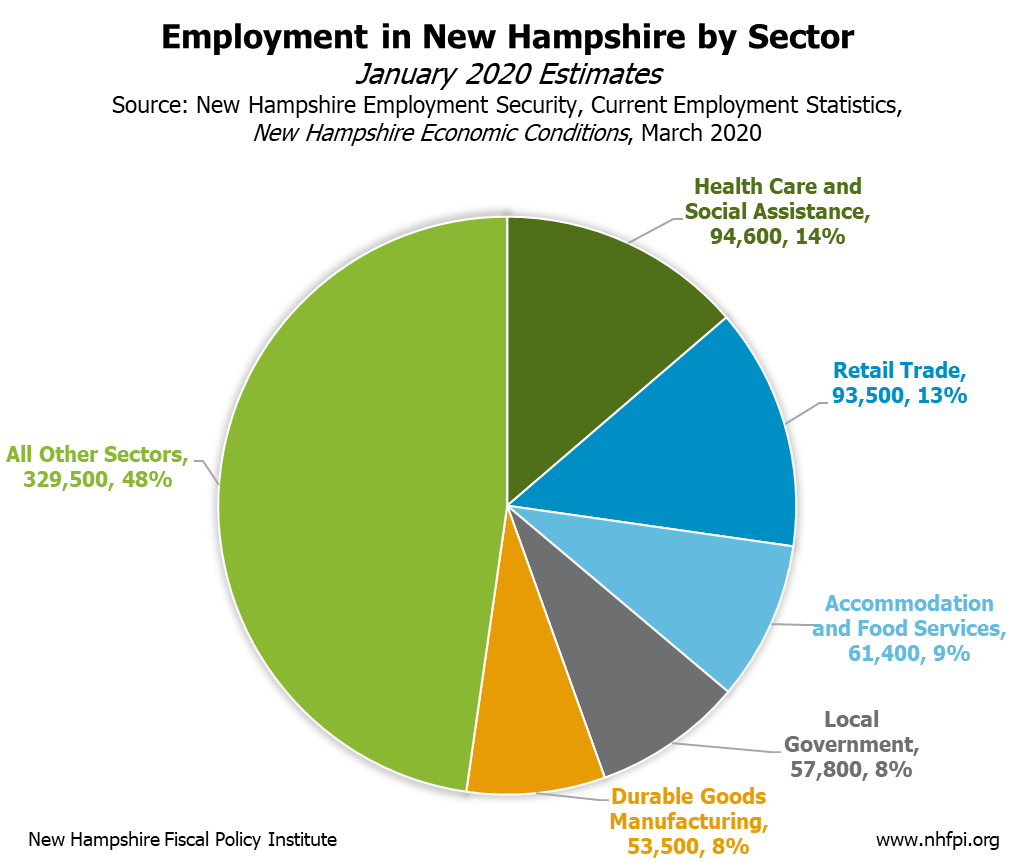

Emergency orders from Governor Sununu, in addition to frequently updated guidelines from the federal government, focus on actions to minimize the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus.[v],[vi] These changes to daily life have curtailed the operations of many businesses, and have initially affected some industries more than others. Industries that are not identified as essential, and those that are unable to easily transition their work to practices that align with orders and guidelines for social distancing, are likely to experience the largest contractions.[vii] With sizable portions of employment in New Hampshire in industries that may be unable to transition to remote work or deemed non-essential, workers in these areas are at the greatest risk of being impacted economically or being exposed to the virus.[viii]

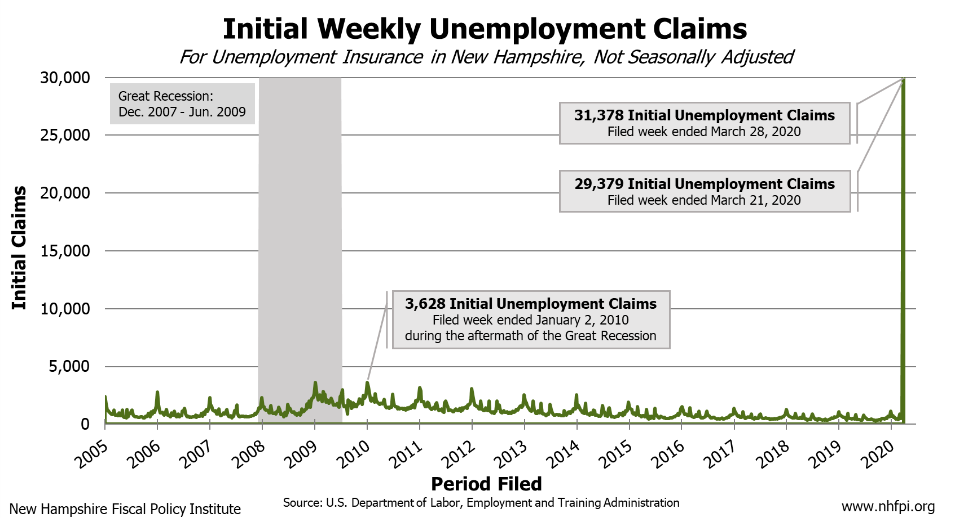

Expansions of unemployment insurance at the state and federal levels have allowed many individuals who have lost jobs or had work hours reduced due to the COVID-19 crisis to file claims for benefits. The initial unemployment claims in New Hampshire filed in the week ending March 21, 2020, provide a glimpse at the unprecedented number of Granite Staters fully or partially out of work. During that week, 29,379 new initial claims were filed, which was a 4,476 percent increase over the preceding week’s 642 initial claims. Initial claims for the following week, ending March 28, 2020, were 31,378.[ix] If all the individuals filing claims in these two weeks remain unemployed and the State’s labor force stays the same size, then the effective unemployment rate in the state would have roughly quadrupled in two weeks, although timing of the data collection for the official March unemployment rate will not reflect that increase.[x] Future initial claims numbers for subsequent weeks are expected to continue at these elevated levels as the crisis continues.[xi] If these initial claims from late March provide insights into future weeks’ initial unemployment claims, and translate to unemployment for an extended time, many lower- and middle-income Granite Staters may be greatly disadvantaged, especially if there is any prolonged delay in the economic recovery from this crisis.

Recovery from the Last Recession Took Years to Reach Many Granite Staters

The COVID-19 crisis began after a long and sluggish recovery from the Great Recession. Despite this previous recession ending in June 2009 and a positive trajectory for most economic indicators, the subsequent recovery period was slow to reach many households.[xii] Increases in inflation-adjusted Gross State Product and the overall addition of thousands of jobs during this time led to notable levels of overall economic expansion. Unemployment also decreased to historically low levels and was below a seasonally-adjusted three percent rate in New Hampshire from December 2015 to February 2020. However, the Great Recession led to the decline of key industries in New Hampshire and negatively impacted the wages of many workers. These labor market shifts, and delays in the economic recovery from the last recession reaching many Granite Staters, has set the stage for the COVID-19 crisis to be potentially severe and cause widespread erosion in the economic security of Granite Staters.[xiii]

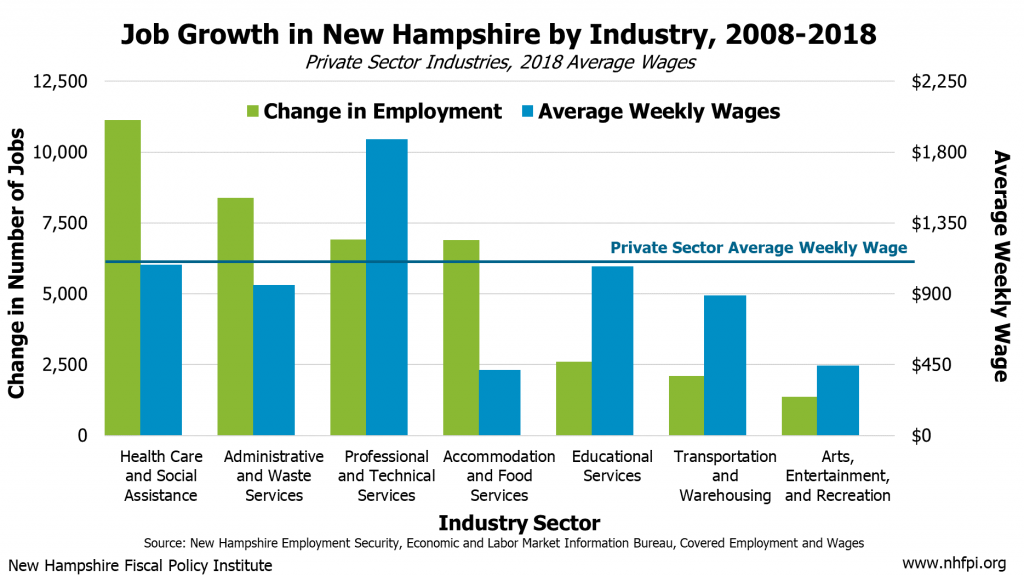

The most recent full calendar year of data for all covered employment and wages by industry in New Hampshire is 2018. Between 2008 and 2018, the highest levels of job growth were in Health Care and Social Assistance, Administrative and Waste Services, Professional and Technical Services, and Accommodation and Food Services. In three of these four industries, average weekly wages were below the statewide average in 2018, which was about $1,106 per week.

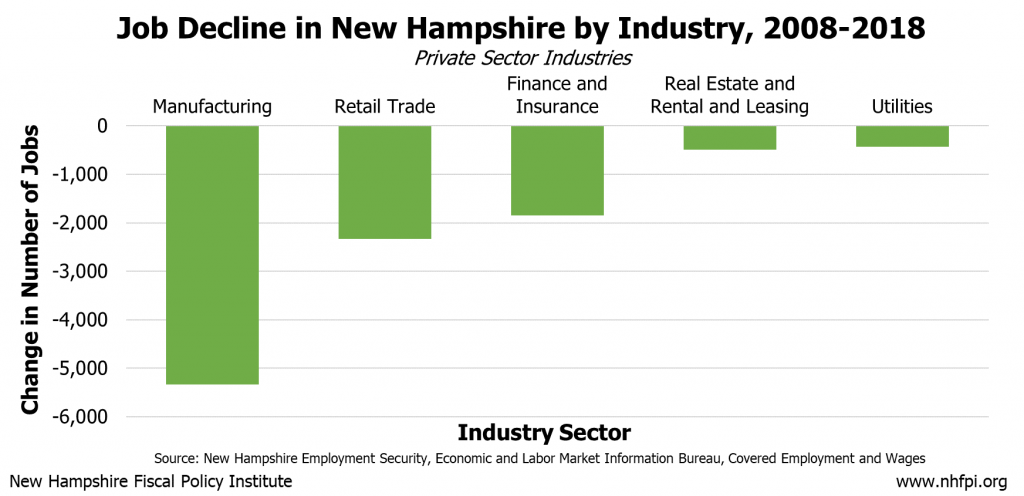

While significant job growth since the Great Recession has occurred in industries with lower than average wages, there have been substantial declines in employment in key industries with higher than average wages. Most prominently, manufacturing, which had an average weekly wage in 2018 of nearly $1,400, was still well below levels of employment seen prior to the Great Recession.[xiv]

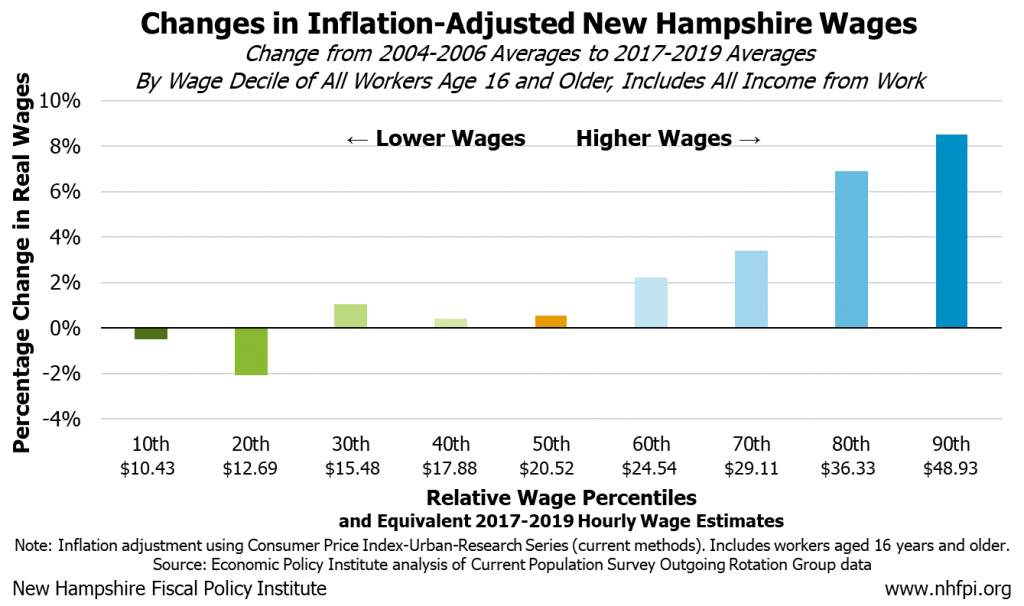

In addition to the changes in employment opportunities following the Great Recession, the rebound of inflation-adjusted wages varied significantly based on wage level. Recently released survey data estimating the wages of New Hampshire workers across all industries in 2019 show lower wages largely have grown to the inflation-adjusted levels from before the Great Recession. However, many Granite Staters with low wages experienced years of declines or only limited growth in their purchasing power before seeing improvements toward the tail end of the economic recovery. Individuals who have consistently been earning above median wages before the Great Recession and through the recovery continued to have the largest increases in their inflation-adjusted wages.[xv]

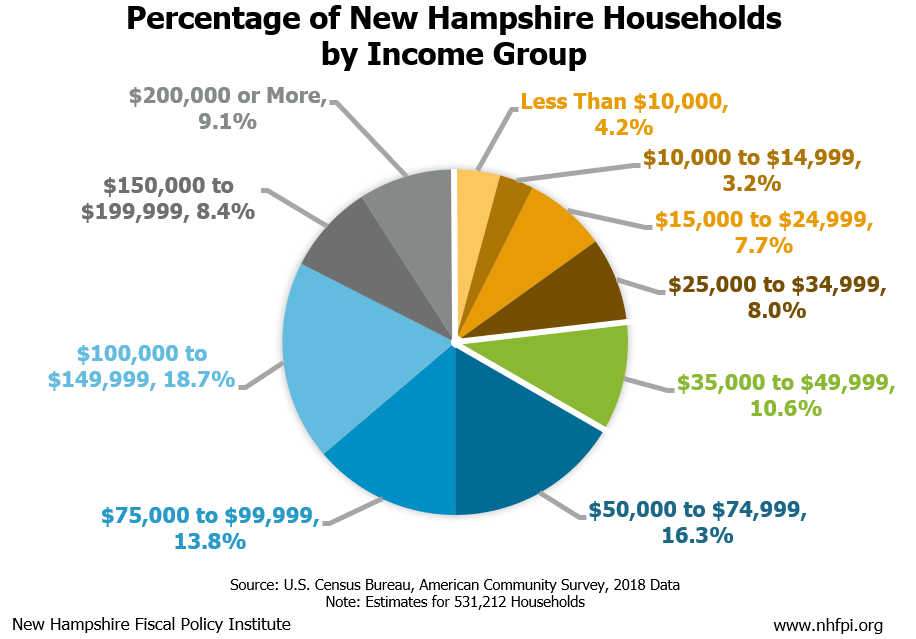

Despite more Granite Staters receiving inflation-adjusted wage rates similar to levels experienced before the Great Recession, many were still struggling to make ends meet prior to the onset of this current crisis. Based on the most recent data, about one in three households in New Hampshire had yearly incomes of less than $50,000, and more than one in five have yearly incomes of less than $35,000.[xvi] Increased expenses for housing and other necessities are difficult for those with lower incomes to absorb. In addition, about four in ten U.S. adults in 2018 reported being unable to cover a $400 unexpected expense with cash, savings, or a credit card to be paid off by the end of the month, indicating these individuals were in a precarious financial position prior to the current economic shock.[xvii]

While many Granite Staters have only recently seen their wages fully recover from the Great Recession, an increase in unemployment and the sharp overall economic contraction caused by the COVID-19 crisis may further diminish their financial security. As the need to physically distance from each other continues, decreases in consumer spending and the inability to safely operate many businesses create conditions for a severe economic decline, and likely a recession, where the negative economic effects may be felt disproportionately by those with lower incomes working in industries like health care, retail, or food and accommodation services.[xviii] Additionally, smaller businesses may fare especially poorly through any extended contraction. Although essential workers at grocery stores, health care facilities, and other needed services may still be present at work, the risk of exposure to the 2019 novel coronavirus in their work environments presents an additional challenge.

Policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis must recognize that supporting those who are the most economically vulnerable, whether as a result of existing financial strains, pandemic-related health expenses, or reduced future income prospects due to the slowing economy, will be key to both the overall recovery and the health and well-being of Granite Staters.[xix]

State and Federal Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis

State Policy Responses

With the Legislature unable to meet due to social distancing restrictions aimed at minimizing health risks, the primary State policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis have been from the Executive Branch. These actions, as of April 10, 2020, include Emergency and Executive Orders from the Governor’s office and policy changes at the New Hampshire Departments of Revenue Administration, Employment Security, and Health and Human Services.

After declaring a State of Emergency via Executive Order on March 13, Governor Chris Sununu issued a series of Emergency Orders critical for both protecting public health and the well-being of those most impacted by the efforts to contain the 2019 novel coronavirus.[xx] Several key Orders protect public health directly by limiting human interaction, including:

- transitioning public schools to serving students in Kindergarten through Grade 12 to remote instruction, extending the period of remote instruction to May 4, and permitting schools to use remote learning platforms that meet minimum standards established in State statute without regard to district data and privacy governance plans during the emergency.

- closure of non-essential businesses and establishing a defined list of essential business activities.

- closure of hotels and other lodging establishments, except for vulnerable populations and essential workers.

- requiring residents to stay in their homes, with exemptions for certain activities related to food, caring for other individuals, and most outdoor recreation.

- prohibiting gatherings of more than 50 people, subsequently reduced to a maximum limit of 10 people.

- requiring restaurants to close dining areas and only provide take out, delivery, or drive-through services.

- modifying requirements around public access to meetings and waiving requirements for the physical presence of the quorum of a public body and for physical access to meetings to the public, so long as meetings be accessible by telephone or electronic means.

- requiring public and private-sector partners to work together to help provide adequate temporary housing or, as necessary, isolate those with COVID-19 symptoms who are experiencing homelessness or who are first responders and health care workers at reasonable risk of exposure to the 2019 novel coronavirus that cannot safely return home.

Other Orders help ensure access to health and other types of services, including Orders that:

- expand access to telehealth services and reimbursement for providers offering these services.

- establish the COVID-19 Emergency Healthcare System Relief Fund, which may disburse up to $50 million in the form of grants or loans to provide emergency relief to all aspects of the New Hampshire health care system.

- authorize temporarily out-of-state pharmacies with investigational drugs for clinical trials to mail these drugs to residents within New Hampshire under certain conditions.

- provide more funding for programs and specialist positions for child protective services and expanding services to include more children, as well as resources to facilitate remote visitations.

- establish the COVID-19 Emergency Domestic and Sexual Violence Relief Services Fund and authorize up to $600,000 for the purposes of assisting crisis centers with the needs of victims, including emergency shelter, and funding operations.

- require health insurers to provide typical in-hospital reimbursement rates, including considering certain out-of-network providers as in-network, for alternative care sites set up by hospitals to care for more patients, regardless of whether treatment is for

COVID-19.

Several of the earliest Emergency Orders issued by Governor Sununu were key for helping ensure the financial security of the many residents impacted by the measures designed to slow the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus, including those seeing dramatically reduced incomes due to job losses of fewer working hours available. These individuals were at risk of losing their housing and key services needed to weather this crisis. The Governor’s Emergency Orders helped to alleviate this situation by:

- expanding unemployment compensation benefits, including partial benefits for reduced work hours, to those who are diagnosed with COVID-19, quarantined or self-quarantined, directed to quarantine by an employer, caring for someone who is quarantined, or caring for a family member or dependent who needs care due to a school or other facility closure.

- eliminating the one-week waiting period for receiving unemployment compensation benefits.

- prohibiting the initiation of rental property eviction processes during the State of Emergency, except for in situations where the individuals have abandoned the rental unit space, have caused substantial damage to the premises, or have created substantial adverse impacts on the health or safety of other individuals residing on the premises.

- forbidding foreclosures after March 17, 2020 and during the State of Emergency.

- prohibiting disconnection or discontinuation of utility services, including electric, gas, water, telephone, cable, internet, or VoIP service, or discontinuation of fuel delivery service, due to lack of payment, and forbidding late fees that would have been incurred during the State of Emergency.

- permitting counties and municipalities to provide blanket abatements of the interest charged on all property taxes not paid on time during the State of Emergency.

These Executive Orders help ensure that individuals economically impacted by the COVID-19 crisis continue to have income supports and places to live even if temporary income supports or reduced levels of income are insufficient to cover usual costs during the crisis. Both homeowners and renters, who have much lower median household incomes than those for homeowners, can defer payments without additional penalty and cannot be removed from their homes for non-payment, in an effort to minimize instances of homelessness.[xxi] However, the Emergency Orders do not remove an individual’s obligation to pay rent or a mortgage; it only removes the threat of removal from housing due to nonpayment temporarily, and individuals and families will still owe accrued rent and mortgage payments at the end of the State of Emergency.

Outside of the Governor’s Emergency Orders, the State agencies have been moving to help residents through the COVID-19 crisis. The New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration has announced it will waive the penalties for most smaller-liability filers of the Business Profits Tax, Business Enterprise Tax, and Interest and Dividends Tax between the typical April 15 deadline and June 15, while offering more flexibility for taxpayers of all sizes to pay returns and quarterly estimated payments based on estimates, rather than final amounts, as long as final payments are made before tax extension deadlines.[xxii] For those claiming unemployment benefits, New Hampshire Employment Security has waived the work search requirement for all claimants.[xxiii]

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services made significant changes to the processes around eligibility for Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and child care assistance. These policy changes, discussed in more detail below, will help ensure that more residents remain enrolled during the COVID-19 crisis, rather than being disenrolled for technical compliance reasons, and focus administrative resources on enrolling eligible individuals.[xxiv]

Federal Policy Responses

The United States Congress has passed three key pieces of legislation as of April 10, 2020 in response to the negative health and economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis. A national public health emergency was declared on January 31, 2020 by the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, which was followed by a proclamation of a national emergency by the President on March 13, 2020, declaring the national emergency began on March 1, 2020.[xxv] In addition to the executive branch powers triggered by a national emergency, three laws passed by U.S. Congress and signed by the President in March included many provisions to combat the spread of the virus and attempt to stabilize the economy and support those affected.

The first major federal legislative response was the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, enacted into law on March 6, 2020 before the current swath of economic impacts were envisioned.[xxvi] This Act provides $8.3 billion in federal funding, divided between supporting research towards vaccines and treatments, to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention other public health agencies, limited disaster relief loans for small businesses, and the international response to the virus. This bill also removes restrictions previously preventing Medicaid providers from using telehealth services to reach all beneficiaries.[xxvii]

The second piece of federal legislation was The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which was signed into law on March 18, 2020.[xxviii] The provisions in this legislation encompass approximately $192 billion to address various aspects of the crisis.[xxix] With respect to monitoring and controlling the spread of the virus, provisions are in place to ensure that those with private or public health insurance will have the costs of testing for the 2019 novel coronavirus covered. States will receive additional funding for Medicaid with an increased matching rate during the public health emergency. In this Act, efforts to stabilize the economy and support those affected by the COVID-19 crisis are considerable compared to the first Congressional response. Key provisions include:[xxx]

- modification to nutrition assistance programs for children and adults.

- Waivers which allow for schools to serve meals and meal supplements in a non-school setting, including allowing for meal pickup options, are available if elected by states.

- The work and work training requirements within SNAP have been waived until the month after the public health emergency is lifted.

- States may request emergency maximum allotments for SNAP enrollees.

- 80 hours of short-term emergency paid sick leave for those working at employers with fewer than 500 employees if they are unable to work or telework through December 31, 2020.

- Full pay leave, up to $511 per day and $5,110 in total, is available if individuals are subject to a quarantine order or recommendation or an isolation order, or they are experiencing symptoms of COVID-19 and need medical treatment.

- Partial pay leave, or two-thirds of regular pay up to $200 per day and $2,000 in total, is available if individuals are caring for someone subject to a quarantine order, a quarantine recommendation, or an isolation order, or someone caring for a child if their school or childcare provider has closed.

- expansion of the Family Medical Leave Act, which is long-term leave, through December 31, 2020 for those unable to work due to the need to care for a child if their school or childcare provider is closed as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

- Employers with fewer than 500 employees are to provide 12 weeks of protected leave for an extended work absence related to the 2019 novel coronavirus. The first two weeks are to be covered by the above emergency paid sick leave, and the following 10 weeks must be paid at no less than two-thirds regular pay, up to $200 per day and $10,000 in total over this period.

- additional emergency grants allocated to assist states in providing and processing benefits and claims, determined by the increase in percentage increase in claims.

- approximately $100 billion in federal payroll tax cuts, as the above sick and family leave wages will not be considered for tax liabilities, in an effort to support the economic well-being of employers.

The third piece of federal legislation was the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, enacted into law on March 27, 2020.[xxxi] This is the most expansive of the three bills passed to date, with more than $2 trillion dollars of provisions for addressing the COVID-19 crisis. States are provided increased Medicaid reimbursement for telehealth and coronavirus related services in addition to direct aid to states. States are also set to receive additional emergency response aid, where New Hampshire is set to receive $1.25 billion in federal funding. Additional key provisions of this Act that provide more robust support to those affected include:[xxxii]

- one-time direct payments, also called recovery rebates, which are anticipated to provide some relief to most individuals being impacted. (These recovery rebates are discussed in greater detail in a subsequent section.)

- lengthening the duration of unemployment insurance benefits by 13 weeks beyond the state-level maximums, and broadening access to individuals not traditionally eligible, including the self-employed and independent contractors. Additionally, benefits have been increased by $600 per week for up to four months, ending July 31, 2020.

- establishing the Paycheck Protection Program with $350 billion in funding, along with another $27 billion in disaster relief loans. These loans are available to small businesses, including self-employed individuals and independent contractors, to help cover expenses and wages throughout the crisis.

- over $500 billion in loans to support larger business and industries, including airlines and businesses important for maintaining national security. States and municipalities may also be eligible to apply for this aid.

An additional $163 billion in other federal appropriations have also been provisioned to assist schools with the transition to remote learning, fund childcare and housing programs, assist with elections, and address other areas impacted by the crisis. Business tax deferments and other aid is also included in this bill. These and other federal policy responses, in conjunction with state-level policy actions, form the short-term steps taken to reduce the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus and lessen the immediate economic impacts of the associated steps to protect public health.

Deployment of Federal Aid to New Hampshire

The federal government does not have to balance a biennial budget and can borrow money for operations regardless of revenues. Most states, including New Hampshire, have balanced budget requirements for operating funds, so federal aid will be critical to help state and local governments through times of high needs for services and low tax revenues.[xxxiii]

U.S. Congress has appropriated additional funding to states to help cover costs associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus.[xxxiv] As of April 10, the most recent and largest appropriations, which were included in the CARES Act, are both for specific purposes and additional general aid to states. Aid designed for specific purposes includes approximately $143 million in aid to New Hampshire for local public schools and to higher education institutions, as well as additional aid to state and local governments for disaster relief, community development programs, and public health agencies.[xxxv] The centerpiece of the aid, however, is the $1.25 billion appropriated to New Hampshire from the federal Coronavirus Relief Fund, which will provide each state with $1.25 billion at a minimum and appropriates more to more populous states.[xxxvi]

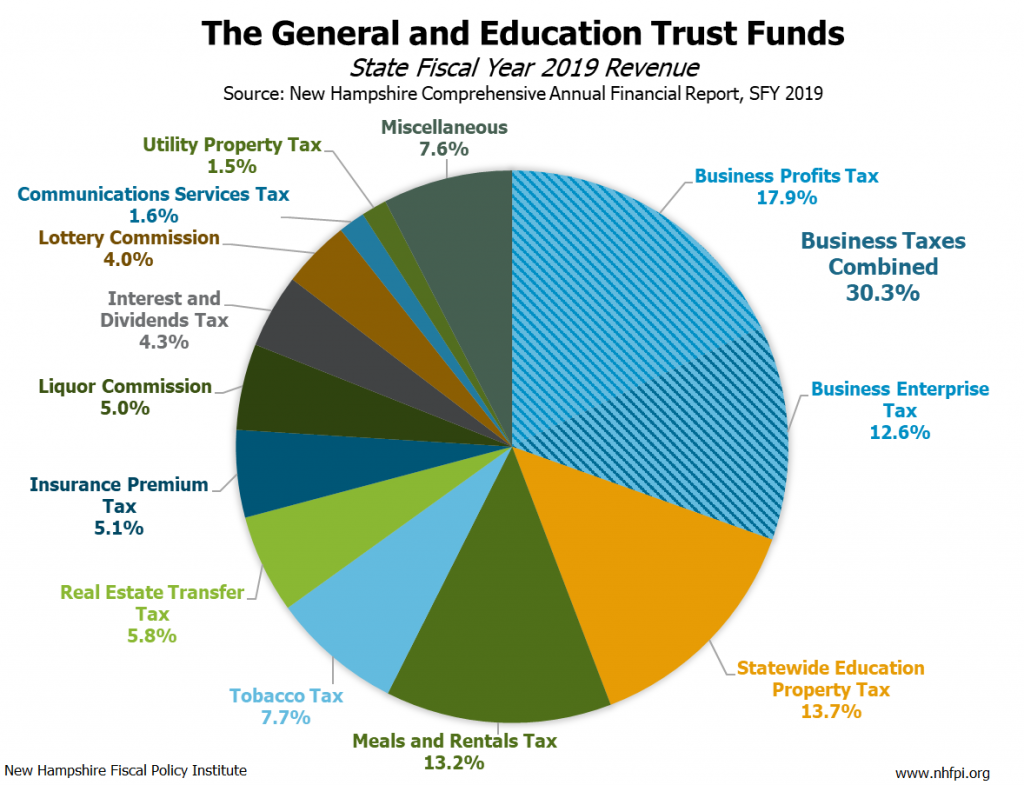

The specific expenses the $1.25 billion coming to New Hampshire can be used for are not clear yet, pending additional federal guidance, but the limits on its use will be critical for understanding how New Hampshire can respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Whether the federal government permits use of Coronavirus Relief Fund appropriations to offset expected drops in State revenue will be key for understanding how much money is available to fund new services and supports alongside the existing, needed commitments in the State Budget. For context, all revenues to the General and Education Trust Funds, where most State tax revenues are deposited, in SFY 2019 totaled $2.64 billion.[xxxvii] The $1.25 billion appropriation could likely fill expected shortfalls in the near-term, but revenue shortfalls could consume a significant amount of the available relief.

The $1.25 billion appropriation to New Hampshire from the Coronavirus Relief Fund must be used before December 31, 2020.[xxxviii] As such, investments must be either temporary and in response to the crisis, or supported by additional future revenues. These funds may provide the state with an opportunity to build a more robust public health infrastructure, support preparedness for future health and economic crises, and help ensure Granite Staters are better able to weather economic challenges and be better prepared for recessions. Undoubtedly, most of these funds will be needed to support state and local governments and private sector or non-profit efforts to slow the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus, treat those suffering from COVID-19, and provide needed economic relief for state residents. Policymakers should carefully consider the short-term needs, which are immense, and the value of long-term investments when deploying these funds in response to this emergency.

Expanded Supports for Granite Staters and Additional Policy Options

The actions taken by federal and state policymakers, outlined above and detailed for key programs below, will provide much-needed assistance to Granite Staters seeking relief from this crisis. However, as rapid implementation occurs to prevent economic free-fall and limit the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus, residents of New Hampshire and the country will likely need additional supports to both withstand and recover from this crisis. State policymakers can play a key role in both providing relief in the short-term and preparing to bolster an economic recovery as public health concerns recede. Several key policy areas and programs will be critical to both the immediate relief and long-term recovery.

Unemployment Compensation Expansions

Unemployment compensation is designed to provide temporary financial assistance to workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own.[xxxix] Traditionally, unemployment insurance benefits in New Hampshire have only been available to those who are out of work, experience a significant reduction in hours, undergo a temporary layoff, or enter certain work training programs. Additional specific criteria, including having sufficient work history within the state, continuing to actively search for work, and being available for full-time work, are traditionally required to receive benefits. Traditional unemployment benefits are only available to individuals unemployed from covered employment, meaning their employer is subject to unemployment compensation law and pays taxes to support unemployment benefits. Due to these requirements, part-time workers were unlikely to be eligible for benefits unless they were available for full-time work, and those who were self-employed or independent contractors could not receive assistance.[xl] Benefits would then be determined based on prior wage rates, and would be provided for up to 26 weeks after a one-week waiting period. These benefits are funded by the Unemployment Compensation Fund, which is supported by taxes paid by covered employers.[xli]

Emergency steps taken by the State of New Hampshire have expanded unemployment benefits and eligibility to more individuals as the scope of the COVID-19 crisis continues to widen. These changes have expanded eligibility to more Granite Staters, including to those facing unemployment or reduced work who are diagnosed with COVID-19, quarantined or self-quarantined, directed to quarantine by an employer, caring for someone who is quarantined, or caring for a child, family member, or dependent who needs care due to a school or other facility closure.[xlii] Additionally, the elimination of the one-week waiting period and the work search requirement, and the increase of the minimum benefit to $168 per week, were key steps to assist those facing the economic impacts of this crisis.[xliii] In addition, the federal CARES Act also took steps to aid those facing unemployment or reduced work during the COVID-19 crisis by providing a federally-funded boost to unemployment compensation of $600 per week through July 31, 2020. The CARES Act also funded the extension of benefits for up to 39 weeks to assist Granite Staters facing job losses or reduced hours. This increase in benefits and eligibility is critical for those impacted by this crisis, as it may provide complete wage replacement for many vulnerable, low-income workers.[xliv]

Depending on the duration of this crisis, additional funding for unemployment insurance may be necessary. Persistent high levels of unemployment, particularly beyond the timeframes currently supported by additional federal assistance, may draw heavily from the Unemployment Compensation Fund. Expanded unemployment benefits, particularly for part-time workers, may also be warranted beyond the end of the State of Emergency. Policymakers should be cognizant of these concerns as the long-term implications of the COVID-19 crisis become clearer.

Direct Tax Rebates and Income Supports for Individuals

In addition to expanded unemployment benefits, one-time direct cash payments from the federal government will be distributed to many individuals affected by the COVID-19 crisis. The CARES Act provision denoted that a direct cash payment of $1,200 will be sent to individuals earning under $75,000 per year as reported on their 2018 or 2019 federal tax returns; couples earning under $150,000 will receive a payment of $2,400. The amounts are designed to taper as income increases. Heads of households will be eligible for the full $1,200 dollar cash benefit so long as their reported income is below $112,500 per year. For all recipients of this benefit, an additional $500 will be provided for each dependent child age 16 years and under.

While these direct tax rebates will be supportive, their effectiveness may be inadequate depending on the severity of the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, several groups of individuals are not eligible to receive this supportive benefit without legislative changes. As written, the legislation contains a gap in which excludes dependents over the age of 16, which includes many young adults and college students, adults with disabilities, and older adults; these individuals will not receive a direct cash payment no matter their income, and the individual who claims them will not receive an additional $500 in assistance as provided for other dependents age 16 and under.[xlv] If this crisis continues to be severe, this gap should be addressed. Future legislation that includes any additional forms of direct stimulus or payment should incorporate all individuals effected, including all dependents. Additionally, those who may have had higher earnings in a previous tax year, but recently experienced substantially reduced earnings, should be considered as well.[xlvi]

Medicaid Policy

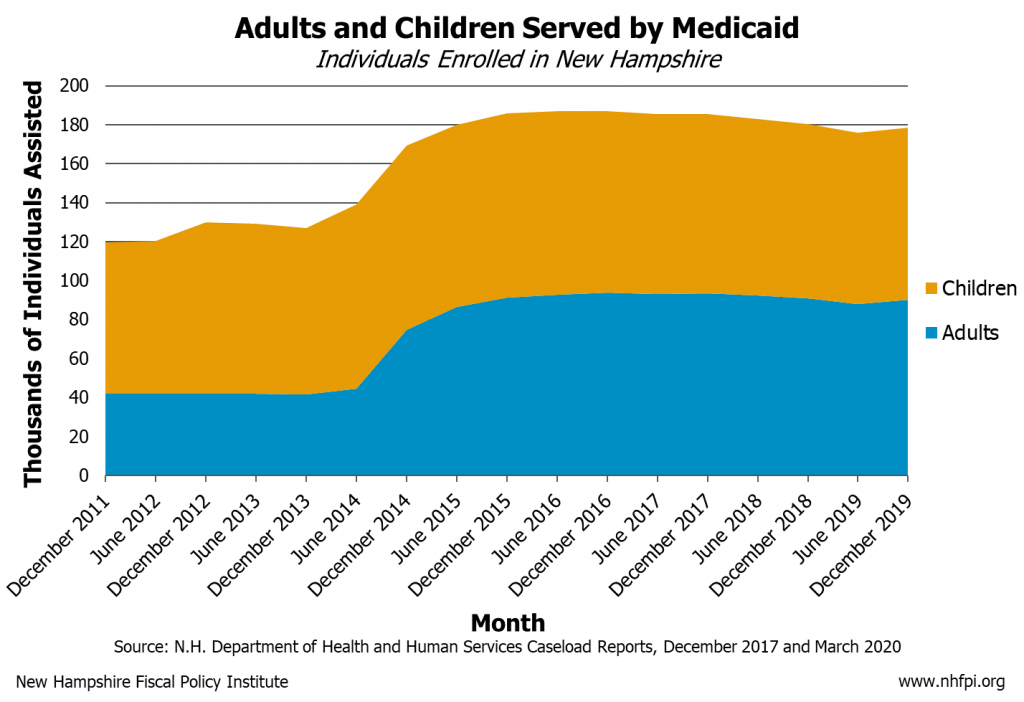

The Medicaid program is a partnership between the federal and state governments to eliminate or defray the costs of health coverage for specific populations with incomes below certain levels. Medicaid covers children, parents, pregnant women, people with disabilities, seniors and nursing home residents, and other individuals with low incomes. Low-income individuals who are not covered in a specific eligibility category are covered by the expanded Medicaid program in New Hampshire, which was created in 2014 and is now named the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program.[xlvii] With the economic shock of the COVID-19 crisis and resulting sudden, high levels of unemployment, Medicaid enrollment, particularly in the expanded Medicaid program, will likely increase.

Medicaid services are funded by a combination of federal, state, and local dollars, supporting a program totaling approximately $2.0 billion in New Hampshire and helping more than 180,000 Granite Staters with limited means access health care.[xlviii] Most services in the program are funded 50 percent by the federal government and 50 percent by the State government; certain nursing home and other long-term supports and services programs are supported by counties more than the State government, and 90 percent of expanded Medicaid service costs are covered by the federal government.[xlix] Certain other programs also have more favorable federal-matching rates.

New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services took steps at the beginning of April 2020 to help support those enrolled in Medicaid and ease access to Medicaid for those who may be most impacted by the crisis. Until May 31, 2020, the Department will not disenroll individuals from Medicaid unless they move out of state, voluntarily choose to end coverage, or pass away. Redetermination for Medicaid eligibility set to take place during this period will be delayed, while passive redeterminations will continue. Additionally, new applicants seeking eligibility for long-term care may provide self-attested income and assets for eligibility determination if the Department is unable to verify financial eligibility using other methods.[l]

The federal government made key changes to Medicaid that will assist New Hampshire and its residents through this crisis. Most critically, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act increased the federal match rate for most Medicaid services temporarily by 6.2 percentage points.[li] This change provides critical supports to states, as it both helps cover increased costs in the Medicaid program from expanding enrollment and more service needs as well as offsets state-level costs. New Hampshire may receive approximately $110 million in additional federal aid from this change, or even larger amounts depending on enrollment and costs.[lii] However, this increased federal match may be insufficient to cover costs or offset state revenue losses, and the match increase does not apply to the expanded Medicaid program. Additional federal Medicaid match increases would provide much-needed relief to states.

The federal government also eased access to Medicaid for those newly unemployed by not including the additional $600 in Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation in the calculations of income for Medicaid eligibility purposes.[liii] This reduces the risk that individuals who have lost employment are not eligible for Medicaid due to receipt of these additional unemployment benefits, which provide supplementary income but do not replace the employer-sponsored health coverage. New Hampshire policymakers can seek to maximize opportunities for presumptive eligibility for Medicaid and temporarily or permanently increase or eliminate certain asset limits for eligibility.[liv]

Food Assistance Programs

The New Hampshire Food Stamp Program, also known by the federal program name Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), provides benefits to households with low incomes in order to reduce food insecurity. Once deemed eligible, benefits are calculated and disbursed so long as income, after certain allowable expenses are deducted, falls below 100 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. For 2019, the applicable federal poverty guidelines for a family of three was a household income of $21,336 per year, according to the New Hampshire Food Stamp Manual.[lv] Benefits can be quickly deployed to support those with lower incomes during times of economic hardship, and SNAP benefits were shown to be an immensely effective economic stimulus during the Great Recession. One estimate from Moody’s Analytics suggested that every dollar invested in SNAP benefits in early 2009 generated $1.74 in economic activity, which was a highest multiplier of any expenditure or tax reduction examined.[lvi] SNAP benefits are fully supported by federal funds, and the administrative costs of the program are split between federal and state government. Other vital food assistance programs that assist children from homes with lower-incomes are the free and reduced-price school meal programs, including programs for lunch, breakfast, and summertime meals.[lvii] Students enrolled in SNAP are automatically eligible for free or reduced-price lunches at school.[lviii]

Steps taken by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, enabled in part by federal legislative changes in response to the COVID-19 crisis, begin to adapt program guidelines to be more responsive to the sharp, unprecedented increase in need anticipated during this crisis. Benefits will be increased to the maximum amount permitted for households, regardless of incomes below the eligibility threshold, during this period for certain households. Additionally, the traditional redetermination and periodic reporting required to verify continued eligibility will be delayed through May 31, 2020. New SNAP applications will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis for individuals unable to produce official income and resource documentation.[lix]

Federal responses regarding food assistance programs were primarily included in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. The Act increased funding to provide temporary maximum benefits to households and assist states with the administrative costs of SNAP and suspended work search requirements for those who are jobless. The Act also targeted more SNAP assistance to students and their families who were enrolled in free and reduced-price school meal programs through school lunch pickup and delivery options and the Pandemic EBT program. The Pandemic EBT program provides SNAP benefits to households whether or not the students and their families were enrolled in SNAP or not prior to the crisis.[lx]

In order to maximize nutritional assistance to disadvantaged households during the COVID-19 crisis, State policymakers could adapt eligibility guidelines of SNAP in New Hampshire to reach more households. Currently, Expanded Categorical Eligibility allows for households with gross incomes of up to 185 percent of federal poverty guidelines, with at least one dependent child and also in receipt of a certain TANF benefit, to be eligible for SNAP and receive benefits as long as household net income is still below 100 percent of federal poverty guidelines. Under federal rules, policymakers have the flexibility to increase the gross income eligibility cutoff to 200 percent of federal poverty guidelines; as of July 2019, sixteen states had set the gross income cutoff at 200 percent, with additional states setting income limits at 200 percent for certain groups or households. State policymakers could also remove the provision requiring a dependent child to live in a household in order for that household to be included under Expanded Categorical Eligibility; of the 40 states with expanded eligibility, only two, including New Hampshire, limit eligibility to a subset of households rather than making it open to all households.[lxi] Additionally, policymakers should implement the Pandemic EBT program in a manner that will best ensure that all eligible students receive this benefit through coordination with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[lxii]

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Supports

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is a broad, federal program that provides block grants to states to use within four broadly-defined areas: providing direct cash assistance to families in need, promoting job preparation and work, reducing pregnancies out of wedlock, and encouraging the formation of two-parent families. This program replaced the previous federal welfare program in 1996, and states have significant flexibility to use these funds within the purposes described in federal law.[lxiii] New Hampshire has used TANF funds for a variety of programs in addition to direct cash assistance to families. However, New Hampshire was projected to significantly draw from the TANF reserve in the currently-enacted State Budget under existing programs, without anticipating the high level of need generated by a sudden and deep economic crisis. The estimated balance of the TANF reserve was $70.1 million at the end of SFY 2017, but was projected to fall to $35.6 million by the end of SFY 2019. The final legislative version of the State Budget projected a remaining balance of $13.5 million at the end of SFY 2021.[lxiv]

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services has already made changes to TANF to ease requirements of enrollees during the COVID-19 crisis. These changes allow for continuous eligibility without redeterminations through May 31, 2020. They also permit hardship extensions to benefits, which are granted for reasons such as loss of employment, lack of adequate child care, disasters or evictions, or health conditions of an individual or household members, to be extended for 90 days starting with March 13, 2020. Finally, the changes also waive the participation rate requirement for work-related activities for 90 days, also beginning March 13, 2020.[lxv]

State policymakers should seek to maximize assistance to families with low incomes and those most affected by the COVID-19 crisis. Federal policymakers provided more assistance targeted at TANF during the Great Recession, but did not provide additional TANF assistance explicitly in any of the three pieces of legislation passed thus far related to the emergence of the 2019 novel coronavirus.[lxvi] State policymakers should deploy available funds, including newly-appropriated federal funds and the potential reallocation of existing TANF funds in response to relevant restrictions placed on federal relief, to maximize the amount of aid available to the families most impacted by this crisis and support New Hampshire’s people and economy through these difficult times.

Childcare Assistance

Programs such as Child Care Scholarships through the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services assist families with low incomes with the costs of care for children up to age 13. This program supports families with incomes below 220 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, while also supporting childcare providers with payments for services.[lxvii]

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the State of New Hampshire has instated new program changes and collaborations to support providers and help ensure care is still accessible to children of parents and caregivers who work in positions deemed essential. Those receiving childcare assistance will not need to be redetermined for eligibility through July 31, 2020, and any cost-sharing portions families were required to pay will be fully covered by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services for eight weeks beginning April 6, 2020. Childcare providers may be able to bill and receive payment at a child’s approved service level whether or not the providers are able to continue operating or the child is unable to attend due to COVID-19.[lxviii] Furthermore, the New Hampshire Emergency Childcare Collaborative, announced in late March with support of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, will provide additional relief. Through this collaboration, certain essential workers may be provided emergency childcare, and child care professionals and centers will be supported through charitable grants and federal Child Care Development Fund dollars.[lxix] Federal provisions present in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act also appropriate additional emergency resources to be provided to childcare programs.

Ensuring that the childcare system remains intact throughout this crisis is of paramount importance, as is making certain that the children of essential workers have access to care. Before the COVID-19 crisis began, access to childcare throughout New Hampshire was limited, which was a challenge for many Granite State families with lower and moderate incomes.[lxx] Investing in childcare providers throughout this pandemic, while increasing support for them in the future, is vital to ensuring access to childcare is available throughout this crisis and when the economy begins to improve.

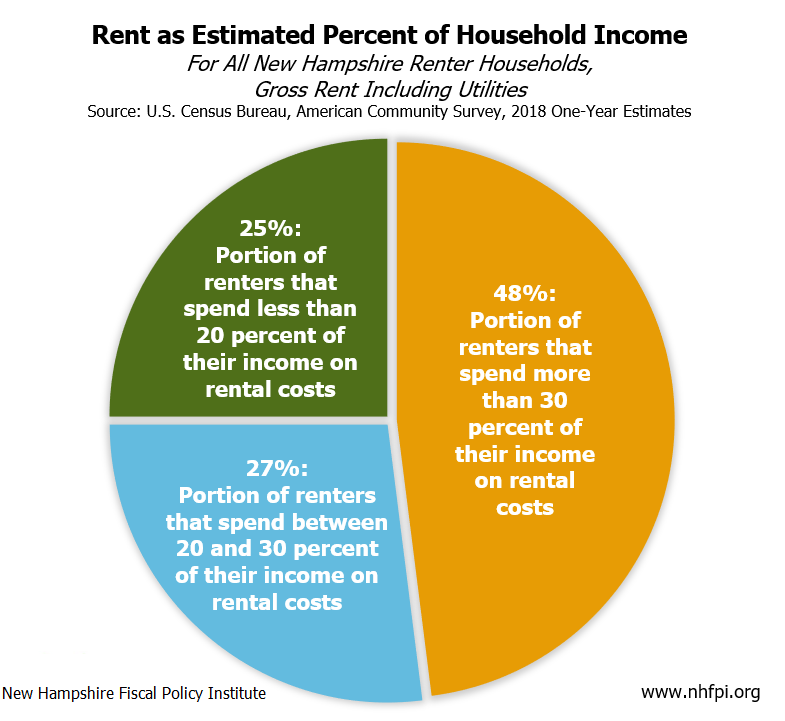

Housing Policy

Even prior to the COVID-19 crisis, the lack of affordable housing in New Hampshire presented a crisis for many individuals and families. Nearly half of all renter households are paying more than 30 percent of their incomes in rent and utilities, exceeding the level at which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers people to be “cost burdened” by housing. Median home prices have been rising faster than inflation, and the number of overall homes listed for sale dropped 41 percent between January 2015 and January 2020, according to the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority.[lxxi]

With the tight housing market increasing rental and purchase prices for years leading up to this crisis, in which incomes are quickly plummeting for many households, keeping up with monthly payments and other housing costs may be very difficult for thousands of Granite Staters. The Governor’s Emergency Orders preventing most rental evictions and foreclosures provides needed immediate relief, but does not eliminate the obligation to pay backlogged bills once the crisis has passed.[lxxii]

The current State Budget includes $4.4 million for emergency rental assistance, funding for rapid re-housing programs, outreach to homeless youth, and homeless shelter case management.[lxxiii] State policymakers should aggressively expand these rental-assistance programs, and consider additional programs, prior to the expiration of the Emergency Orders preventing most evictions and foreclosures. Renters have lower median incomes and are less likely to have savings or access to credit than homeowners. Beginning payment assistance programs before the Emergency Orders expire would also permit landlords to pay their expenses and help maintain stability in the real estate market.[lxxiv] Providing robust support networks for those who have become homeless and finding housing alternatives rapidly may also minimize the risks of long-term poverty and financial instability for those individuals.

State Revenue and Budget Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis

The extent of the negative impact to the economy of this crisis is not known, but State revenues will certainly be insufficient to cover planned State Budget expenditures and the additional costs incurred in the crisis response. As of the end of March, before most of the impacts of the crisis would be experienced in State revenue streams, actual receipts were on track with the State Revenue Plan for the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund combined. However, the undesignated revenue surplus had declined to $900,000 (0.048 percent), a negligible amount in the scope of operations supported by these funds. Such a small surplus is unlikely to sustain significant operations when subsequent months bring total revenues into deficit relative to the State Revenue Plan.[lxxv]

State Revenue Declines in the Great Recession and Potential Differences in the COVID-19 Crisis

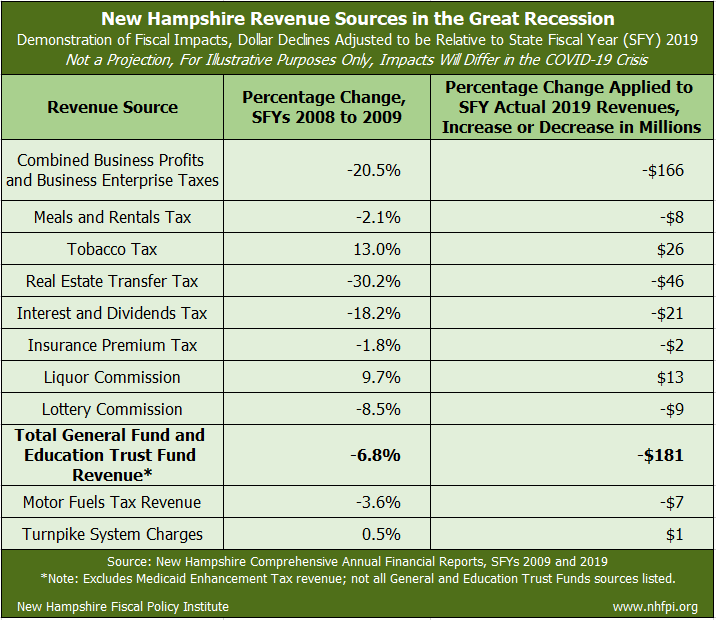

Although this economic contraction is very different than any experienced in the United States in at least the last century, State revenue impacts from the most recent recession may provide informative points of comparison. The Great Recession began relatively slowly in December 2007 and officially lasted until June 2009, followed by a long, slow recovery period in New Hampshire.[lxxvi] The largest drop in State revenues was from State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2008, which began July 1, 2007, and SFY 2009, which ended June 30, 2009, the same month as the Great Recession formally ended. Combined revenue to the General and Education Trust Funds, excluding federal transfers and other funds transferred through executive orders, were 6.85 percent ($155.7 million) lower in SFY 2009 than in SFY 2008. For context, 6.85 percent of SFY 2019 General and Education Trust Funds revenue would be $181.1 million.[lxxvii]

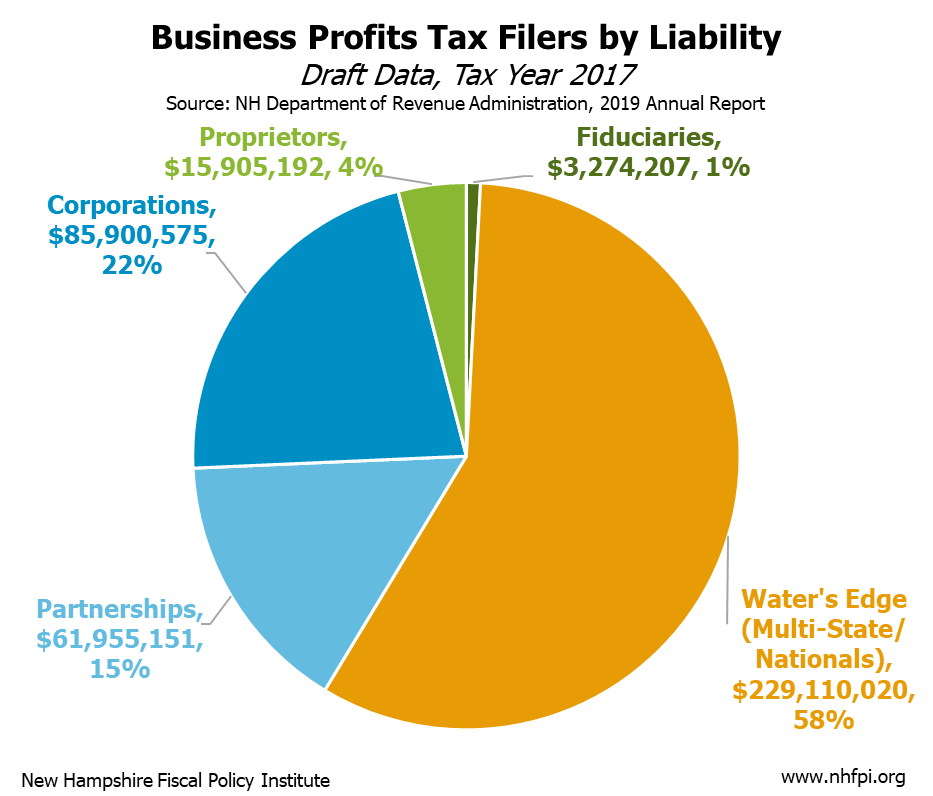

While not all revenue sources trend with the overall economy in New Hampshire, economic activity in key sectors and statewide impacts key revenue streams, including the Business Profits Tax, the Business Enterprise Tax, the Meals and Rentals Tax, the Real Estate Transfer Tax, the Interest and Dividends Tax, and others.[lxxviii] New Hampshire’s economy matters disproportionately for many of these revenue sources, but national trends also have significant influence; this is particularly true for the Business Profits Tax, for which large multi-state and multi-national corporations are a critical part of the tax base.[lxxix] Between SFY 2008 and SFY 2009, the average, inflation-adjusted quarterly value of U.S. Gross Domestic Product declined by 2.5 percent. In the worst quarter of the Great Recession (the last quarter of calendar year 2008), the economy contracted by 2.2 percent unannualized. While any projections for the future of the economy at this stage require significant assumptions and modeling, with high degrees of uncertainty, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office projected in early April that U.S. Gross Domestic Product in the second quarter of 2020 may decline by 7 percent unannualized, which would be reported as a 28 percent annualized decline by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.[lxxx]

Although the magnitude of the revenue impacts from the current crisis relative to the Great Recession are not known, the drop in receipts will likely be much more immediate. The Meals and Rentals Tax, New Hampshire’s third largest tax revenue source, will likely decline precipitously during the curtailment of restaurant activities. Taxes on purchased restaurant meals and other prepared food accounted for approximately 80 percent collected by the Meals and Rentals Tax in SFY 2019, with the remainder from hotel and lodging stays and rental cars. Receipts may not recover to the $361.3 million in State revenue generated during SFY 2019 for SFY 2021, either, as some restaurants may have permanently closed and residents may have less disposable income even if public health precautions permit reopening restaurant dining areas.[lxxxi] Receipts from other revenue sources, such as the two primary business taxes, the tax on motor fuels, Turnpike tolling, profits from the Liquor and Lottery Commissions, the Interest and Dividends Tax, and the Real Estate Transfer Tax may decline quickly as well.

Additionally, while revenues are expected to decline precipitously, the need for services has increased dramatically. Both unemployment compensation and Medicaid are likely to see substantial increases in enrollment, as people lose jobs and see incomes decline. Although additional federal funding is key to stemming the impact of the growth of need in these areas, the State will still be responsible for portions of the increased needs.[lxxxii] Previously-identified State Budget priorities, such as treatment for substance misuse and mental health needs and addressing education funding inequities, will not disappear, and the needs in these areas will likely be exacerbated due to this crisis.[lxxxiii] The expanded Medicaid program in New Hampshire, the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, will likely see additional enrollment as more individuals lose employment, and thus begin to draw upon Liquor Commission revenues as provided for in the last State Budget. The addition of this new revenue source was designed to prevent a funding shortfall in the expanded Medicaid program; this funding shortfall would have triggered the program’s termination before the addition of this new funding source in the most recent State Budget.[lxxxiv]

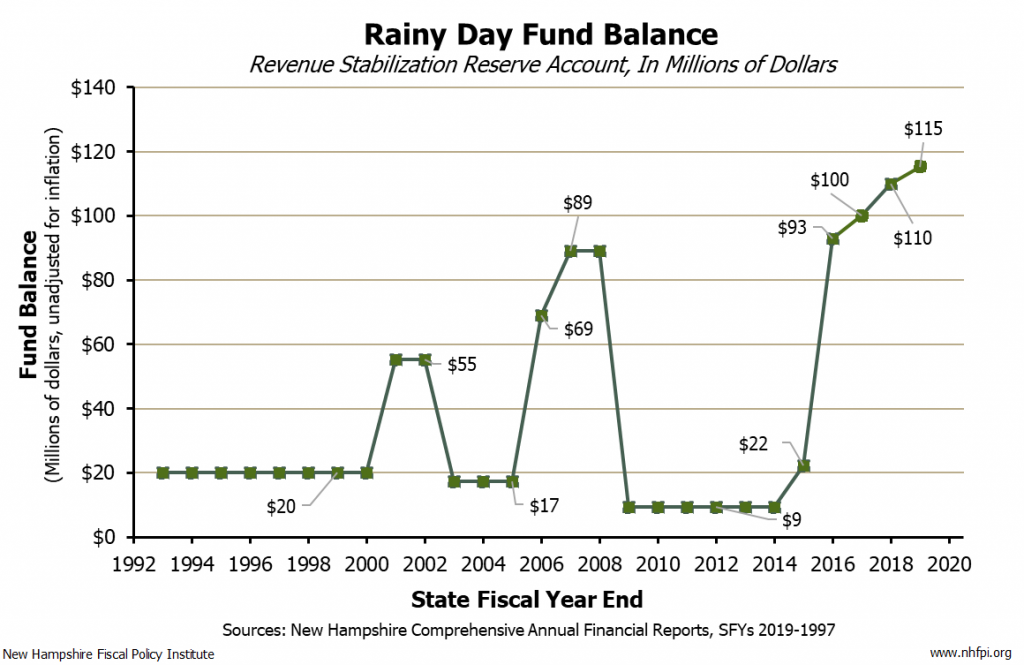

Recession Preparedness and the Rainy Day Fund in New Hampshire

The State’s Rainy Day Fund has been bolstered in recent years and stands at the highest levels recorded since it was established in 1986. At nearly $115.3 million, the Rainy Day Fund has not been filled, but has a balance greater than the SFY 2019 individual annual yields of several key State revenue sources, such as the Interest and Dividends Tax or transfers from the Lottery Commission. The Rainy Day Fund also holds primarily General Fund surplus dollars, which means State policymakers have a high degree of flexibility as to how those dollars are deployed, as long as the Governor and at least two-thirds of each chamber of the Legislature agrees on those uses.[lxxxv]

While it is a significant resource, multi-state research suggests the Rainy Day Fund does not leave New Hampshire well prepared for a recession relative to other states. Moody’s Analytics performed a virtual fiscal “stress test” on states in 2019 based on projected Medicaid cost increases and revenue declines in scenarios of moderate and severe recessions, with the severe recession scenario mirroring the Great Recession. The analysis found that New Hampshire was one of ten states with budget shortfall of greater than five percent in the case of a moderate recession, and projected New Hampshire would have an approximately 10 percent budget shortfall in a severe recession. However, the modeled severe recession was not nearly as sudden or steep as the COVID-19 crisis will likely be, based on available projections, although the economy may recover more quickly from the COVID-19 crisis as well.[lxxxvi]

In March 2020, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities conducted an analysis, which incorporated the Moody’s Analytics stress test results, of a broader examination of the manner in which both states and their residents might fare in a recession. The analysis considered four categories, each with sub-elements: state revenue reserves, strength of unemployment insurance systems, accessibility of Medicaid and ease of enrollment, and affordability of public higher education. New Hampshire ranked in the bottom ten states in three of the four categories, with only accessibility of Medicaid pushing New Hampshire’s ranking higher, with three out of six identified Medicaid sub-elements fulfilled.[lxxxvii]

State policymakers should deploy resources from the Rainy Day Fund swiftly to provide support to the economy, and should use the flexibility of these dollars to supplement federal funds or other resources dedicated to specific purposes. Guidance on federal relief dollars from the CARES Act is still forthcoming, and limitations on the use of those funds will inform the best deployment of the Rainy Day Fund. In particular, the ability to use federal funds to cover revenue shortfalls is a critical consideration. However, State policymakers can seek to raise other revenue to fund future activities or offset shortfalls during the budget biennium, whereas massive needs and demands on essential services exist in the short term. Helping to alleviate the immediate needs may reduce long-term damage to the health and financial well-being of individuals and the overall economy. Immediate needs include supporting New Hampshire’s health care infrastructure and workforce and eliminating the planned $25 million back-of-the-budget reduction to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, which will need both appropriated and additional resources to address the COVID-19 crisis.[lxxxviii] Policymakers should consider methods for supporting immediate needs, including drawing from the Rainy Day Fund, in the context of the availability of federal and other funds to provide rapid support for Granite Staters.

Considerations and Options for Raising Revenue

Revenue policy changes in response to a recession may impact individual, family, or business budgets, but may be required to fund and maintain necessary services for the most vulnerable Granite Staters in this time of crisis. In the immediate response to the Great Recession, New Hampshire policymakers increased Tobacco Tax rates, increased the Meals and Rentals Tax rate and made changes to the tax base, altered the Interest and Dividends Tax base, instituted a tax on gambling winnings, and adjusted various fees.[lxxxix] This current economic contraction may require additional adjustments, depending in part on the federal response, to help ensure that needed services are fully-funded. Policies that increase revenues to the State should seek to generate revenue from those with the greatest ability to pay, while avoiding disproportionate impacts on individuals with low incomes and those most affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

Business Taxes – Current State law requires rate increases in the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax if combined revenues for the General and Education Trust Funds fall more than six percent below the State Revenue Plan for SFY 2020. This provision is designed to help ensure that services funded in the State Budget could be supported in the case of a revenue shortfall, which the State is about to experience. The trigger should be permitted to function as intended, increasing tax rates with a revenue shortfall, or accelerated given the known need for more revenue in this environment.

Additionally, policymakers should consider seeking additional revenue through the Business Profits Tax. While the Business Enterprise Tax impacts smaller businesses and local operations whether they are profitable or not based in part on compensation paid to employees, the Business Profits Tax base is comprised of profits generated and includes multi-national corporate profits, which comprise a significant portion of the tax base.[xc] Many of these entities received a significant tax break following the December 2017 federal tax overhaul, when the top federal corporate income tax rate was reduced from 35 percent to 21 percent.[xci] From 2001 until 2016, New Hampshire’s Business Profits Tax rate was 8.5 percent, and in subsequent years was reduced, resulting in a rate of 7.7 percent for tax year 2020.[xcii]

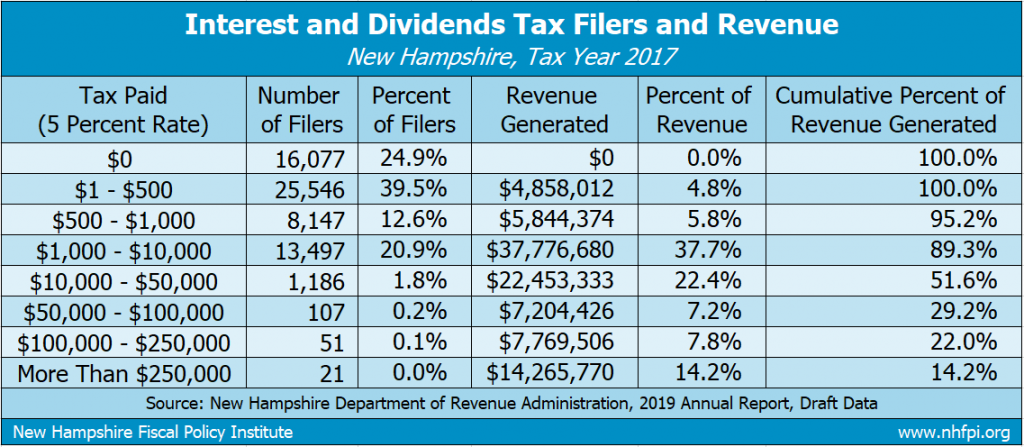

Interest and Dividends Tax – Individuals, estates, or partnerships must own assets from which they can collect sufficient interest, dividends, or distributions to have an Interest and Dividends Tax liability in New Hampshire. For single filers, the first $2,400 of this income is exempt from taxation, rising to $4,800 for joint filers and with additional breaks for those who are age 65 and older, have a disability, or are blind.[xciii] This tax is primarily paid by those collecting relatively high levels of income in this manner. More than half of the tax revenue in tax year 2017 was generated by the approximately 2.1 percent of all filers owing more than $10,000 in Interest and Dividends Tax, indicating that, at the five percent tax rate, the majority of income was collected from filers reporting more than $200,000 in taxable income from interest, dividends, distributions, and any other taxable non-wage income.[xciv] Raising more revenue through the Interest and Dividends Tax, while increasing exemptions for taxpayers collecting limited amounts of otherwise taxable income, would likely primarily raise revenue from those with more available assets to weather the COVID-19 crisis than most individuals.[xcv]

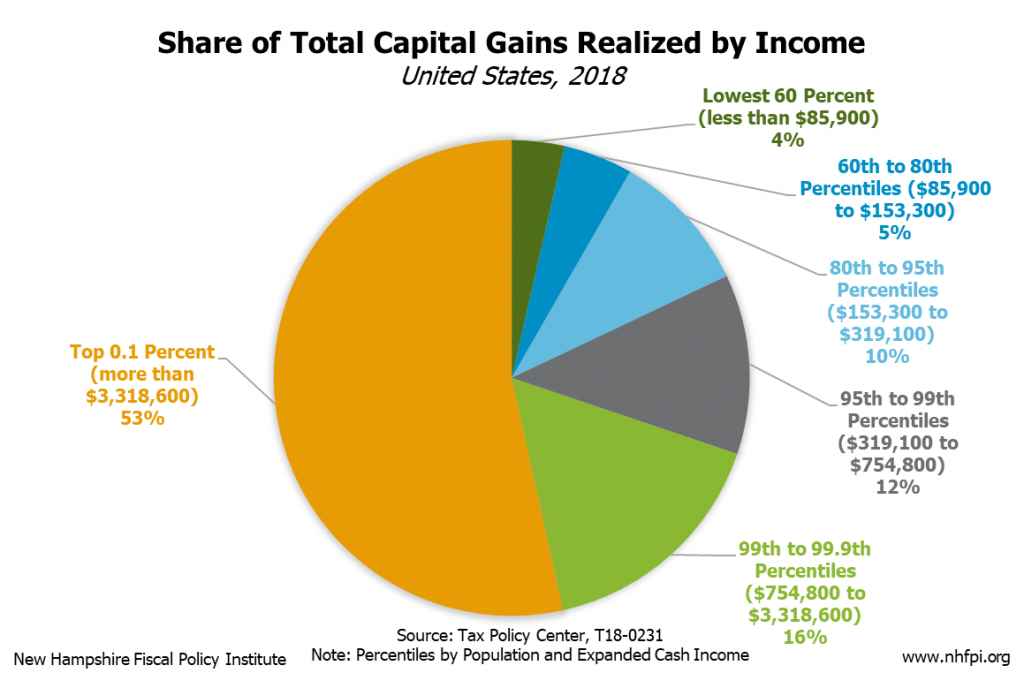

Additionally, expanding the Interest and Dividends Tax to include capital gains would largely collect revenue from those who already have high incomes and may be less likely to see their financial stability critically threatened by the COVID-19 crisis. Using data from the United States as a whole, the Tax Policy Center estimated that about 90.2 percent of all capital gains went to the top 20 percent of income earners, which was about $153,300 per year in cash income and certain benefits, during 2018. The top one percent of income earners, or those with incomes of about $754,800 per year or more, accounted for 68.7 percent of all capital gains, and approximately 52.6 percent went to the top 0.1 percent, or those with more than $3.3186 million in income.[xcvi]

Motor Fuels Tax – According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the price for a gallon of regular gasoline in New England has dropped from $2.48 per gallon on March 2, 2020 to $1.94 on April 6, 2020.[xcvii] In both the current State Budget and the prior State Budget, surplus General Fund revenues, largely generated by higher-than-anticipated business tax receipts, were used to eliminate anticipated shortfalls in the Highway Fund, for which the tax on gasoline and diesel fuel is the largest source.[xcviii] The Motor Fuels Tax was raised from $0.14 per gallon to $0.16 per gallon in 1990, $0.16 to $0.18 gallon in 1991, and then not again until it was adjusted up by 4.2 cents to $0.222 per gallon during 2015, where it remains today.[xcix] The Motor Fuels Tax is not adjusted for inflation, and has not been sufficient to meet the long-term road and bridge infrastructure needs expected of its contribution to the Highway Fund; the Legislature has appropriated additional infusions of General Fund support for the Highway Fund in the last two State Budgets. Gasoline purchases may be well below normal for some time, gasoline prices themselves are considerably lower, and available surplus General Fund revenues to support Highway Fund operations are very unlikely, suggesting a Motor Fuels Tax increase may be warranted. Increasing the Motor Fuels Tax may disproportionately impact people with lower incomes, so policymakers should seek to offset costs or increase services for those individuals in other ways.

Tobacco Tax – At $1.78 per pack of 20 cigarettes, New Hampshire has the lowest Tobacco Tax rate of any state northeast of West Virginia. That low rate likely generates significant cross-border sales. Maine’s rate is $2.00 per pack of 20 cigarettes, while Vermont’s is $3.08, and Massachusetts has a rate of $3.51. Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York all have rates at or above $4.25 per pack. [c] The Tobacco Tax is not adjusted for inflation, and New Hampshire could boost the cigarette tax rate considerably while retaining or matching the lowest rate in the region.

Other Potential Revenue Sources – Policymakers seeking additional revenue may also examine taxation of certain transactions or selective sales, especially for products that may be considered nonessential or luxury goods. Taxation of estates or inheritances at times of transfer, which New Hampshire previously taxed under existing law from 1931 to 2004 but no longer does due to a federal tax change, may also generate revenue from existing assets.[ci] The State could collect excess revenue generated through the Statewide Education Property Tax, which currently remains with communities that have higher levels of property wealth relative to student populations, and consider adjusting the targeted amount raised by the Statewide Education Property Tax, which has not been adjusted since 2005.[cii] Fees or fines set in statute should also be periodically revisited, as most are not automatically adjusted for inflation or increased costs, but fees and fines may disproportionately impact people with low incomes and should not be relied upon as a major source of revenue.

Targeted Tax Relief

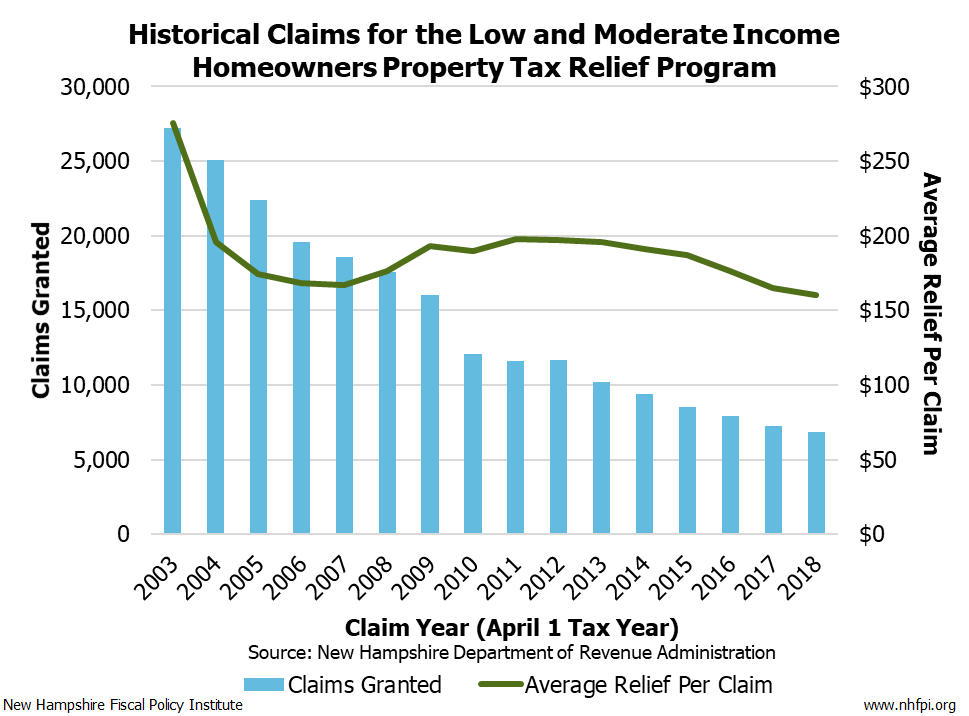

Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief Program – An existing State program provides a partial rebate against the Statewide Education Property Tax based on a homeowner’s income. Individuals must earn less than $20,000, or $40,000 for a married couple or head of household, to qualify initially; the rebate increases as income drops. The rebate does not reduce the local property tax base, as the rebate is paid out of State Education Trust Fund appropriation. The income thresholds were set in law in 2001 and have not been adjusted for inflation since that time. Additionally, the average property tax relief per claim was approximately $160 in tax year 2018, while the total property tax levied per each individual person in New Hampshire was approximately $2,886 in 2019.[ciii] Expanding this program to be a more substantial rebate, potentially incorporating consideration of the school or other local property tax levy, would likely provide relief to many homeowners facing hardships paying their bills in a manner that is means-tested and would not erode local property tax bases. Adjusting the target amount to be raised by the Statewide Education Property Tax upward would also provide the opportunity for a tax rebate that would be a more significant portion of the total property tax levy. Additionally, awareness of this program should be promoted, as use as been declining in recent years. Recipients of aid through existing anti-poverty programs, such as Medicaid or SNAP, should automatically receive notification that they may be eligible. Policymakers could also incorporate small businesses whose operations are severely curtailed due to the COVID-19 crisis into this tax rebate program temporarily as well.

Ongoing Investments and Federal Support in the Future

Policymakers seeking to raise additional revenue have a wide variety of options, including several outlined here. Additional State revenue will very likely be needed, unless federal support is dramatically increased and few restrictions are placed on funds made available, to provide care and services for Granite Staters during the COVID-19 crisis and help ensure continuity of services for needs that already existed prior to the onset of this crisis. Both the short-term and long-term impacts of this crisis, and building resilience for the next crisis, will require both immediate and longer-term methods for supporting investments.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis presents a challenge unlike anything Granite Staters have faced in a century. The initial economic impacts have already been severe, with more hardship yet to come. The policy responses at both the federal and state levels have been bold, but more actions will be needed to help ensure the equitable recovery and well-being of all Granite Staters.

This Issue Brief reviews several key issues important to addressing New Hampshire’s current situation:

The COVID-19 crisis is both a public health crisis and an economic crisis. Many people throughout New Hampshire are suffering directly from the health impacts of COVID-19. Many more Granite Staters are caring for a loved one affected by the health impacts and are providing additional care and education duties for their children. Residents of all ages are facing greater strains on their mental health due to stress or anxiety. Across the state, households are seeing their incomes drop or financial security diminished due to the necessary measures to limit the spread of the virus. The combination of these factors will collectively take an immense toll on the well-being and prosperity of Granite Staters.

The crisis is disproportionately impacting people who are the most vulnerable. The negative health consequences may be more severe for older adults and individuals with serious underlying medical conditions. Limitations on interactions will affect those already in need of regular health or other assistance services, such as those experiencing disabilities or requiring mental health or substance misuse treatment. Workers in health care and social assistance, which is estimated to be the largest employment sector in the state, are performing critical services and may be at higher risk of exposure to the 2019 novel coronavirus. Additionally, this crisis will disproportionately affect those with low incomes and limited resources. People who already had lower average wages, including those in retail, accommodation, or food services, are more likely to have seen their incomes decline rapidly or their work disappear.

The economic impacts are more sudden, and have triggered a steeper decline, than the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. Early data suggest the number of people who may be counted as unemployed in the state quadrupled in just two weeks, and this may be an undercount. The long-term economic impact of this crisis is not yet known, but will depend in part on the duration of the public health risk. Despite the most recent economic recovery being the longest recorded in the United States, the economic growth did not reach all Granite Staters equally, and many only recently had their purchasing power return to levels experienced before the Great Recession. This long-term limitation on purchasing power has left many Granite Staters less prepared for this crisis.

Federal and state policymakers have responded quickly, but more action will be needed. Federal policymakers have swiftly moved to appropriate significant resources for economic relief, with expanded unemployment compensation benefits, cash assistance to most low- and middle-income residents, and fiscal aid to states. The Governor has made emergency orders critical for limiting the spread of the virus, preventing evictions and utility shutoffs during the crisis, expanding eligibility for unemployment compensation, and providing assistance to the state’s health care systems, among other actions. State departments have expanded food assistance benefits, waived certain unemployment compensation requirements, and provided relief for certain late tax filers. However, the speed and severity of this crisis, and the need to move beyond relief and catalyze the subsequent economic recovery, indicate more action and resources will be needed to build an economy that lifts all Granite Staters.

Key existing programs can be bolstered to support Granite Staters. State policymakers can continue to expand access to food assistance and unemployment compensation, extending key changes beyond the crisis and into the economic recovery. State policymakers should also provide additional housing supports both during and after the crisis, as current measures delay required payments but do not defray them, and help childcare systems recover and expand. Federal policymakers should provide an enhanced Medicaid funding match to states and provide more funding to offset losses in State revenue.

State revenues will decline sharply, and may not recover fully for an extended period. Key revenue sources will likely be severely impacted immediately while others may see latent reductions, but the overall effect will shift the State Budget out of balance in the near term as costs increase and revenues decline. Two recent multistate analyses suggest New Hampshire is not as well prepared as other states to absorb the impacts of a recession. Although funds available to the State depend in part on the size and nature of federal assistance, State policymakers will likely have to find ways to raise additional revenue to both support short-term services and invest in long-term economic resiliency. Policies that increase revenues to the State should seek to generate revenue from those with the greatest ability to pay, while avoiding disproportionate impacts on individuals with low incomes and those most affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

Targeted tax relief would assist those with the least ability to pay. The State should expand the existing Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief program to aid taxpayers impacted by this crisis. This program currently offsets only a small portion of typical property tax costs, and could be expanded to temporarily include small businesses or work in conjunction with assistance programs for low-income renters.

As New Hampshire moves through this crisis, the state will need to consider both short-term needs, such as current health care system capacity and immediate income supports for residents, as well as long-term economic stimulus, such as education aid, infrastructure improvements, and targeted assistance for vulnerable individuals. Critically, many of the pre-existing concerns facing New Hampshire, including the availability of substance misuse and mental health services and inequities in access to health care and education, will likely be exacerbated by this crisis. Sustained investments will be key for both individual financial stability and the economic recovery. Establishing a strong foundation to help all Granite Staters rebuild their economic security, and better weather any subsequent crises, should be the paramount concern for the state’s leaders as New Hampshire moves through and beyond the COVID-19 crisis.

Endnotes

[i] For more information on the potential health risks associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus to specific populations, see the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), People Who Need to Take Extra Precautions.

[ii] For more information on the COVID-19 crisis and mental health, see the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), Stress and Coping, and the Mayo Clinic, Covid-19 and Your Mental Health.

[iii] A recent report by MorningStar analyzes potential economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

[iv] Economic forecasts provided by the Congressional Budget Office emphasize the uncertainty of estimates at this time.

[v] A full list of emergency orders is available via Governor Sununu’s website.

[vi] Guidelines for protection of personal health and minimizing community spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus are available via the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[vii] For discussions of the sectors that may be most affected during this crisis, see the Urban Institute’s UrbanWire piece published on March 17, 2020 titled The COVID-19 Recession Will Be Different.

[viii] See the Boston Federal Reserve’s Issue Brief titled The Effects of the Novel Coronavirus Pandemic on Service Workers in New England, published March 31, 2020.

[ix] Updated advance and initial unemployment claims are released by the U.S. Department of Labor each Thursday.

[x] See the March 17, 2020 Unemployment News Release from New Hampshire Employment Security. The household survey to evaluate the unemployment rate for the month will be based on the week including March 12, before the most severe economic impacts of the efforts to prevent the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus began in New Hampshire. For more information, see the Economic Policy Institute, Which Data to Watch and Not Watch This Week, April 1, 2020.

[xi] The Economic Policy Institute projects that 16.3 percent of New Hampshire private sector jobs may be lost by July 2020.

[xii] The National Bureau of Economic Research Business Cycle Dating Committee’s report officially recognizes the Great Recession as lasting from December 2007 through June 2009.

[xiii] For more information on trends and analyses of the recovery period after the Great Recession, see NHFPI’s August 2019 Issue Brief titled New Hampshire’s Workforce, Wages, and Economic Opportunity.