The House version of the State Budget would significantly enhance funding for local education in New Hampshire. The proposal would deploy an additional $165.3 million to local public education over the biennium, directing additional ongoing aid primarily to communities with relatively low property values per student and high percentages of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals. These communities either have a limited property tax base from which they can draw to fund education locally, a relatively large number of students who are from households in or near poverty, or both, indicating their local fiscal capacities are more constrained as they have more limited abilities to raise revenue for education on a per-student basis. Funds to support these communities with limited means would be raised by expanding an existing tax to include capital gains, which are disproportionately received by individuals with high overall incomes. The House budget would also provide school building aid and increase State aid for kindergarten students.

Schools could use the additional aid to reduce property taxes, support additional services, or a combination of both. Supporting low-income students with additional aid to school districts, particularly those school districts where many students face limited means at home, increases potential opportunities for those children and encourages both upward mobility for individuals and future vibrancy in areas with less economic activity.

This Issue Brief draws from NHFPI’s Issue Brief on the House budget proposal, The House State Budget for State Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

A Summary of Adequate Education Aid Policy

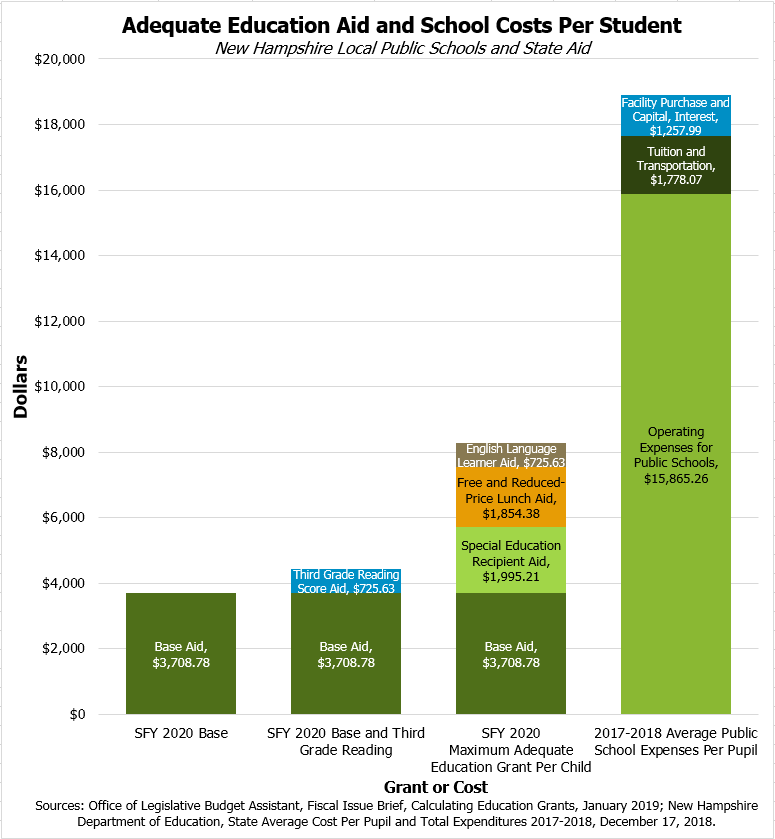

Currently, State law distributes funding to local public school districts through Adequate Education Aid, which is determined on a per-student basis. Funding is assigned based on the municipality that is home to the student, and funding flows to the local public school district or charter school the student attends. Public schools, which enrolled 173,433 students in October 2018 in non-charter schools, receive a base amount of funding from the State per student.[i] That base Adequate Education Aid amount for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2020 is $3,708.08 per pupil. The State provides upward adjustments on a per-student basis, including (for SFY 2020) an additional $725.63 per pupil identified as an English language learner, $1,854.38 for a student eligible for the Free and Reduced-Price School Lunch Program[ii] (FRL), and $1,995.21 for a special education student. Students not eligible for any of those three categories of additional aid may trigger an allocation of $725.63 over the base grant if the student scores below proficient levels on the State third grade reading assessment.[iii] Public charter schools, which do not levy property taxes, are provided funds through the per-student funding formula and are provided additional per-student grants as well; they served 3,932 full-time equivalent students in October 2018.

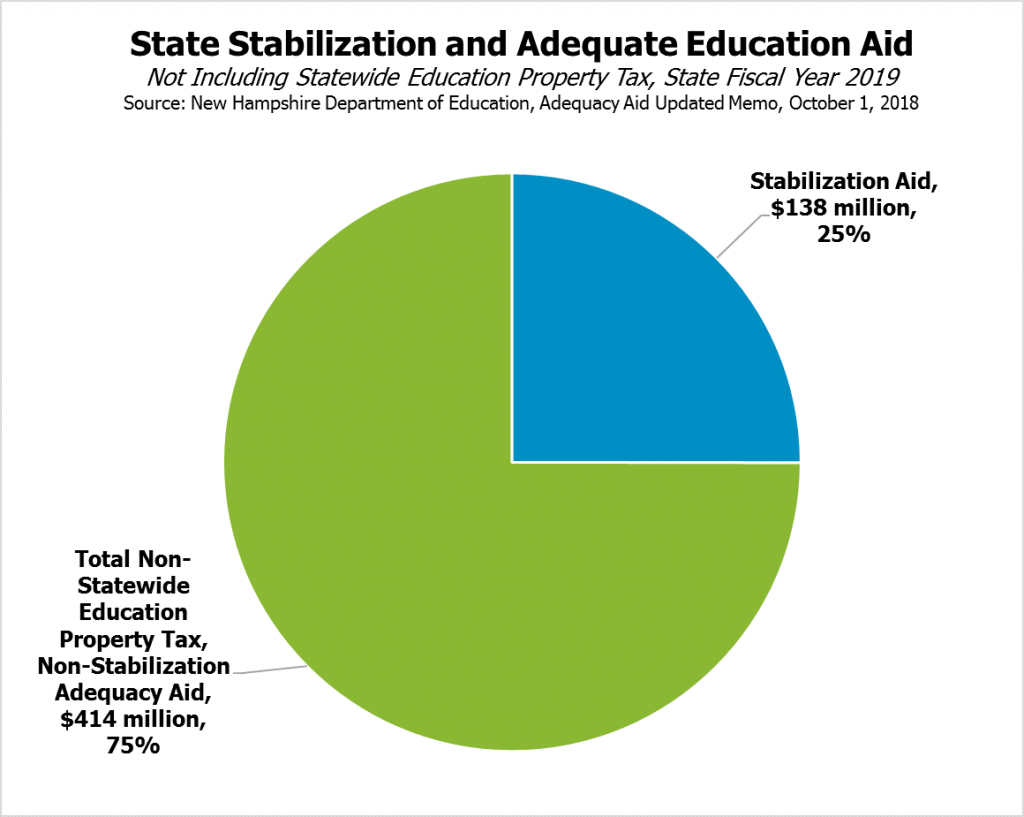

Stabilization Grants are another significant component of Adequate Education Aid. These grants were designed to keep cities and towns that would have been appropriated less education funding in SFY 2012, after a changed formula took effect, than in SFY 2011 at their prior levels. This aid amounted to about $158.5 million each year from SFY 2012 through SFY 2016. A phase-out of this aid began in SFY 2017, reducing the total amount by 4 percent of its original value per year and dropping to about $138.2 million in SFY 2019.[iv]

Any costs not covered by the State are paid with local property taxes, which accounted for about 61.5 percent of revenue in 2017-2018, with additional assistance from federal or other grants and much smaller local or district revenue sources.[v] School districts report substantially higher per pupil costs to the State than the base grant amounts provide. School districts reported a statewide average operating cost per pupil of $15,865.26 for the 2017-2018 school year, with the inclusion of certain tuition, transportation, capital items, debt payments, and facility construction and acquisition bringing the average per pupil cost to $18,901.32.[vi]

In total, Adequate Education Aid amounted to $915.7 million in SFY 2019. That total includes approximately $363.1 million raised and retained locally through the Statewide Education Property Tax, $138.3 million in Stabilization Grants, and $414.1 million in grants to fulfill the Adequate Education Aid formula’s per-student grants beyond the level funded locally by the Statewide Education Property Tax.[vii] Adequate Education Aid is paid out of the State’s Education Trust Fund.

Adequate Education Payments to Local Public Schools

The House budget would substantially increase State support for local public schools, making changes to the Adequate Education Aid formula that disproportionately benefit schools with more students with low incomes, as determined by FRL eligibility, and students who live in municipalities with lower property values per student.[viii] The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant has published estimates by municipality as to the amount of aid each would receive under the new formula, which would take effect in SFY 2021.[ix]

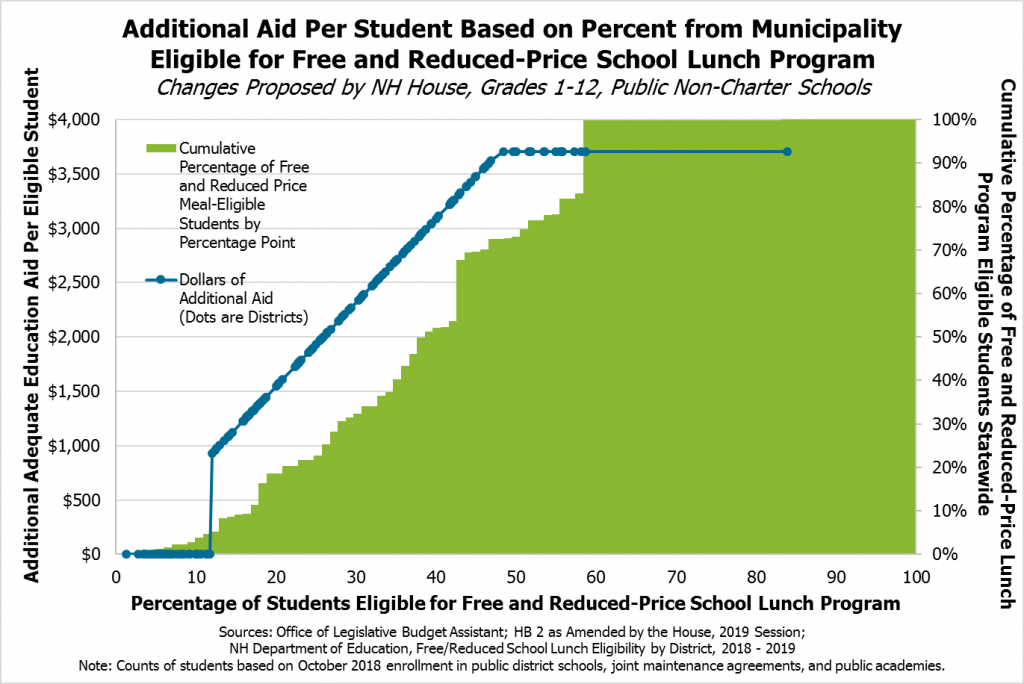

The House would augment the existing Adequate Education Aid formula by adding additional aid for schools with higher percentages of FRL-eligible students and for school districts with less property value per pupil. For school districts with 48 percent or more students who are FRL-eligible, an additional $3,708 would be provided for each pupil eligible, essentially doubling the base adequacy amount provided for those pupils.[x] In October 2018, sixteen school districts had more than 48 percent of FRL-eligible students. These districts accounted for approximately 13.2 percent of Grades One through Twelve students enrolled in New Hampshire in October 2018, and 27.5 percent of all FRL-eligible students. School districts with less than 12 percent of their students identified as FRL-eligible, which included about 20.8 percent of all public school district students and 5.2 percent of FRL-eligible students, would not see an increase in aid under the House proposal. Districts with between 12 percent and 48 percent of pupils eligible would receive at least $927 and up to $3,707.23 per eligible student, based on a sliding scale calculation.

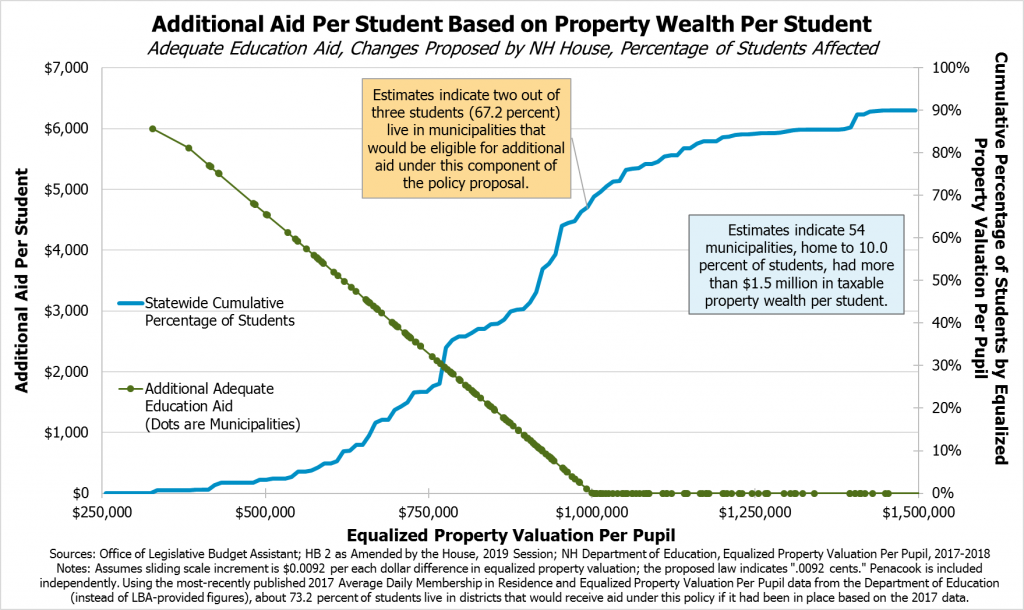

Additionally, the House budget proposes adding an additional grant of $6,000 per student for a municipality’s school districts where the equalized property valuation per pupil, a measure of taxable property wealth, is $350,000 or less. In 2017, the equalized valuation per pupil was lower than $350,000 only in Berlin. Additional fiscal capacity aid would be distributed based on property values per pupil for municipalities with over $350,000 in valuation per pupil, falling on a sliding scale to $0 for municipalities with a valuation per pupil of $1,000,000 or greater. The statewide equalized valuation per pupil in 2017 was $1,043,647, and the median municipality had $981,629 in taxable property wealth per student. Based on available estimates, two out of every three students (67.2 percent) live in municipalities that would be eligible for this subsidy.[xi]

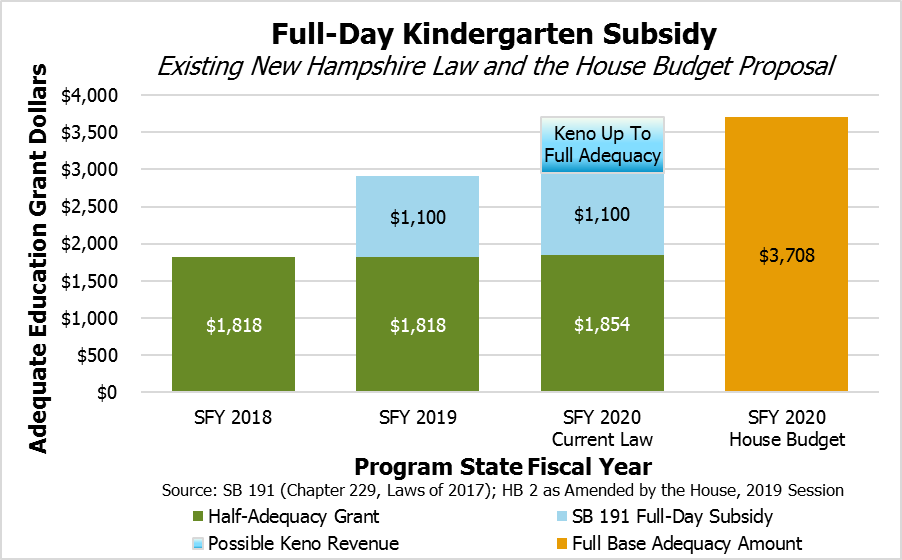

The House would include kindergarten students fully into the Adequate Education Aid formula. Currently, kindergarten aid is set at half of the base Adequate Education Aid amount, or $1,818.03 in SFY 2019 and $1,854.04 in SFY 2020, with an additional $1,100 provided per pupil in SFY 2019. Starting in SFY 2020 under current law, additional aid up to the full Adequate Education Aid amount would be provided dependent on revenue collected from Keno gambling, with $1,100 guaranteed to be provided. The House budget, starting with SFY 2020, would fund kindergarten students at the same level, and using the same differentiated aid factors for upward adjustments, as students in Grades One through Twelve.[xii]

While the additions to the Adequate Education Aid funding formula would take effect in SFY 2021, the House budget would restore the full stabilization grant amount from SFY 2016 to local governments in SFY 2020, adding approximately $25.3 million in Adequate Education Aid. Stabilization grants would be eliminated under the House budget in SFY 2021, supplanted by the new formula changes. Once the new formula changes take effect, Adequate Education Aid would be limited to a 20 percent increase in aid per municipality from the prior year in SFY 2021 and 2 percent growth in each subsequent year. No municipality would receive less Adequate Education Aid than in the previous years with the exception of municipalities that raise more than needed to fund the State’s Adequate Education Aid through the Statewide Education Property Tax. This tax is a State tax, but is raised and retained locally, meaning municipalities that have a small number of students relative to their property wealth keep the additional revenue from this tax, rather than sending the excess to the State for distribution elsewhere.[xiii] This retained amount in property-wealthy municipalities is projected to total $26.2 million in SFY 2020 under the House budget proposal. These municipalities would not be guaranteed to be appropriated the same Adequate Education Aid they received the prior year.[xiv]

Increased kindergarten aid and the increased stabilization grants would together contribute an estimated additional $34.8 million in SFY 2020 under the House budget. The additions to the Adequate Education Aid funding formula for students eligible for free and reduced-price meals and for fiscal capacity disparities based on property values, combined with the increased kindergarten aid, would add about $130.5 million in Adequate Education Aid in SFY 2021 relative to current law.[xv] The House budget would also add explicit Adequate Education Aid use and reporting requirements for school districts in statute.

School Building Aid, Other Education Aid, and the Education Trust Fund

The House voted to lift the current moratorium on accepting new school building aid projects and provide an additional $19.3 million through the existing program from the Education Trust Fund (ETF). The school building aid program, which subsidizes local costs for school building construction or acquisition, has not accepted new projects since SFY 2010 with one exception, but has been paying for the costs of past projects since the moratorium, with diminishing appropriations over time.[xvi] The House also voted to draw from the ETF and send funds to local schools for education-related aid to fully fund anticipated special education for students who have higher cost needs and provide an additional $4.6 million in tuition and transportation aid to school districts, aimed at fully funding anticipated tuition and transportation aid to school districts.

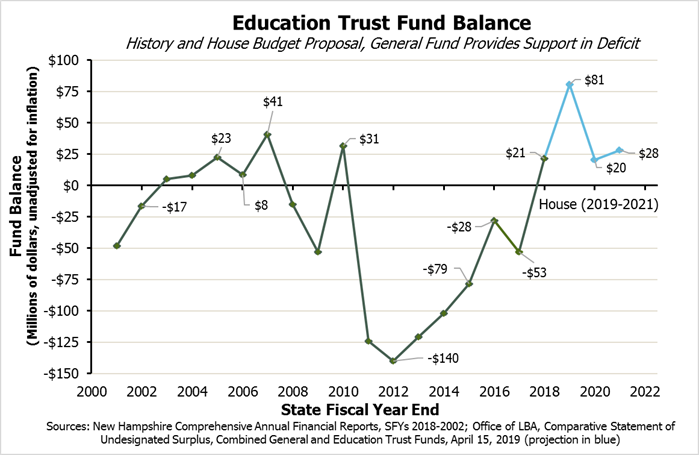

While the House plan would draw significantly on the ETF, it would also add revenue and projects to retain a positive balance in the ETF. The ETF is required to retain any surplus at the end of a State fiscal year, rather than allowing it to lapse to the General Fund. In most years, the ETF runs a deficit and must be supported by a transfer from the General Fund, but surplus revenue resulting in part from one-time effects following the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act have pushed the ETF into surplus, which it retains absent other changes in law.[xvii]

Funding Education by Expanding the Interest and Dividends Tax to Capital Gains

The House budget proposed to modify the existing Interest and Dividends Tax (I&DT) to include capital gains in the tax base, with the expected increase in revenue dedicated to the Education Trust Fund.[xviii] Capital gains result from the sale of an asset at a higher price than the purchase price amount. Capital gains from certain sales, such as sales of stocks and bonds held as investments or most real estate sales with gains over $250,000 for an individual or $500,000 for joint filers, are taxed under federal law and would be taxed at a 5 percent rate under the House budget proposal.[xix]

Although current New Hampshire law does not include all capital gains for individuals in a tax base, national data provides information about who the capital gains tax might affect most in New Hampshire. New Hampshire does tax capital gains in limited circumstances under the Business Profits Tax. However, New Hampshire law states that income taxable under the current I&DT is not taxable under the Business Profits Tax, and the House proposal would not change that exemption after the expansion of the tax base to include capital gains. This may reduce the tax rate for some taxpayers from 7.9 percent under the Business Profits Tax as proposed by the House budget to 5 percent under the Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax.[xx]

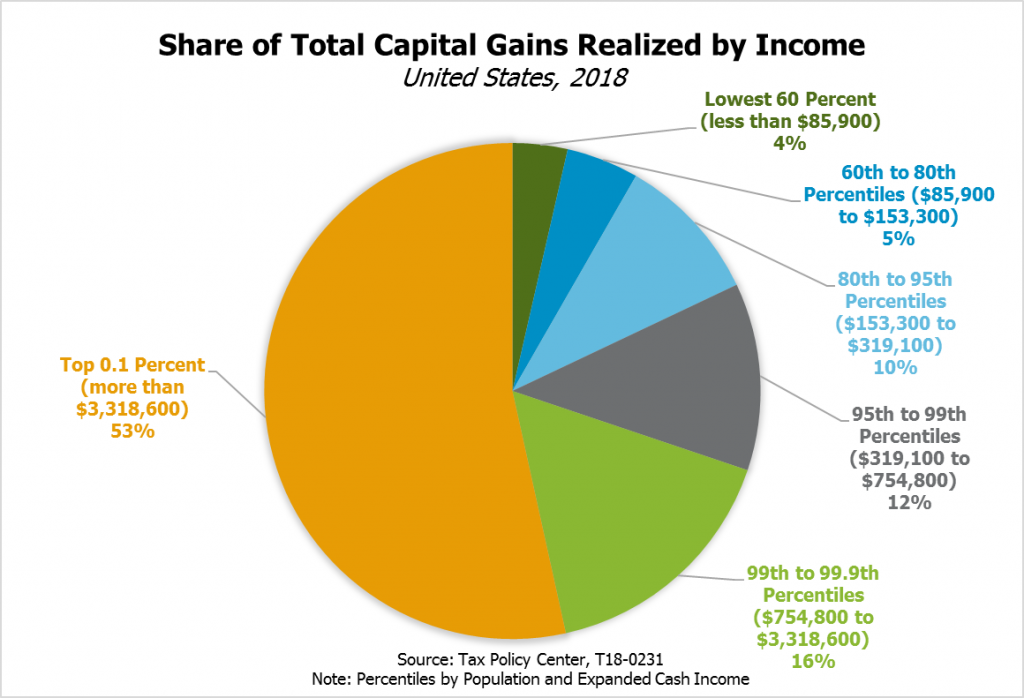

Capital gains taxes are likely to be disproportionately paid by high-income people. Using data from the United States as a whole, the Tax Policy Center estimated that about 90.2 percent of all capital gains went to the top 20 percent of income earners, which was about $153,300 per year in cash income and certain benefits, during 2018. The top one percent of income earners, or those with incomes of about $754,800 per year or more, accounted for 68.7 percent of all capital gains, and approximately 52.6 percent went to the top 0.1 percent, or those with more than $3.3186 million in income.[xxi]

The House budget would also change the filing thresholds for the I&DT, raising them to exempt more people from the new combined Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax. While the current filing threshold for the I&DT is $2,400 for an individual, partnership, limited liability company, or association, the House proposal would raise the filing threshold to $5,000 during a tax year, with income below those thresholds exempt. Joint filers would be exempt up to $10,000, up from $4,800 under current law. The House also voted to amend the statute to increase the additional income exemption for those aged 65 years and older from $1,200 to $7,500, increase the income exemption from $1,200 to $2,500 for those who are blind, and from $1,200 to $2,500 for those under age 65 who have a disability and are unable to work.

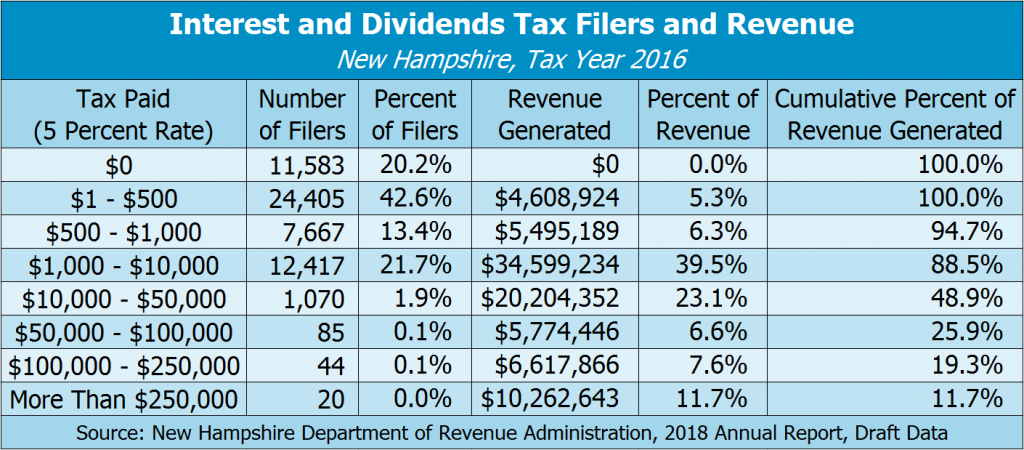

Increasing these exemptions would likely reduce State revenue collected through the traditional I&DT base and would reduce the number of individuals filing under the current I&DT. About 20.2 percent of I&DT filers for tax year 2016, the most recent year with published data, did not owe any tax, while another 42.6 percent of filers owed between $1 and $500. A tax liability of $500 indicates that the taxpayer had $10,000 of taxable income from interest payments, dividends, stock distributions, and other liabilities in the current I&DT base. Of the revenue generated by the I&DT, only 11.5 percent came from those who owed less than $10,000 in tax year 2016; this indicates those filers who had more than $200,000 in income from non-wage, non-capital gains, interest, dividend, and distribution income that was taxable under the I&DT paid 88.5 percent of the revenue in tax year 2016. Increasing exemptions would likely decrease the number of taxpayers paying relatively small amounts in I&DT while preserving most of the tax base, which is disproportionately comprised of high-income individuals.[xxii]

New Hampshire’s I&DT generated $105.8 million in revenue during State Fiscal Year 2018.[xxiii] The House budget projects expanding the I&DT to include capital gains would generate an additional $150 million in revenue each year. The House budget would appropriate the first $150 million generated by the Interest, Dividends, and Capital Gains Tax to the Education Trust Fund, primarily to pay for increased aid to property-poor school districts and those schools with more students from households with low incomes.

Study Commission

Although the House proposed redrafting the education funding formula in a manner that does not sunset or expire, the House proposal would also examine various options to fund local schools in the future. The House budget would appropriate $500,000 to fund a commission to study school funding, including “whether the New Hampshire school funding formula complies with court decisions mandating an opportunity for an adequate education for all students, with a revenue source that is uniform across the state” and identifying trends and disparities in student performance. Funding for the commission would support independent staffing as well as the utilization of independent school finance experts. If this commission were to be established, it would likely inform local school funding decisions in the next State Budget.

The State Budget debate has moved from the House to the Senate, which is scheduled to vote on its own version of the State Budget by June 6. For more on the State Budget process, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource and NHFPI’s NH State Budget web page.

Endnotes

[i] These counts are conducted based on an October 1 census of school district attendance. For related data, see the New Hampshire Department of Education, State Totals – Fall Enrollments by Grade, 2018-2019.

[ii] Children are eligible for the Free and Reduced-Price School Lunch Program if their household incomes are below 185 percent of the federal poverty threshold. For a family of two, 185 percent of the federal poverty threshold in 2019 is $31,284, and it is $39,461 for a family of three. In New Hampshire, students are also eligible if anyone in the household is enrolled in the New Hampshire Food Stamp Program or the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or if the applicant is a foster child. For more on the National School Lunch Program as a measure of poverty, see the National Center for Education Statistics, “Free or reduced price lunch: A proxy for poverty?” NCES Blog, April 16, 2015. For more on poverty thresholds and for tables showing the different thresholds for family sizes, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs, HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2019. For more information, see the New Hampshire Department of Education’s National School Lunch Program Application Materials.

[iii] For more on the method for determining Adequate Education Aid currently in place, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Fiscal Issue Brief, Calculating Education Grants, Traditional Public Schools, January 2019.

[iv] To see a summary of the Stabilization Grant calculation method, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Fiscal Issue Brief, Calculating Education Grants, Stabilization Grants, January 2019. For historical data on Stabilization Grants, see New Hampshire Department of Education, State Aid Programs.

[v] To learn more about school district revenue sources and expenses, see the New Hampshire Department of Education, State Summary Revenue and Expenditures of School Districts, 2017-2018.

[vi] For a full breakdown of reported costs, see New Hampshire Department of Education, Office of School Finance, State Average Cost Per Pupil and Total Expenditures 2017-2018, December 17, 2018.

[vii] For a full breakdown, see the New Hampshire Department of Education, State Aid Programs, Final Adequacy Aid 2019, March 6, 2019. For more on the Statewide Education Property Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[viii] Children are eligible for the Free and Reduced-Price School Lunch Program if their household incomes are below 185 percent of the federal poverty threshold. For a family of two, 185 percent of the federal poverty threshold in 2019 is $31,284, and it is $39,461 for a family of three. For more on the National School Lunch Program as a measure of poverty, see the National Center for Education Statistics, “Free or reduced price lunch: A proxy for poverty?” NCES Blog, April 16, 2015. For more on poverty thresholds and for tables showing the different thresholds for family sizes, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs, HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2019. For more on property values in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s August 2018 Issue Brief Measuring New Hampshire’s Municipalities: Economic Disparities and Fiscal Capacities.

[ix] To see a distribution of the aid anticipated on a municipal-level basis, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Education Funding Analysis, Preliminary Estimates – For Discussion Only, 2019-1232h, March 24, 2019. The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant produced updated estimates on April 25, 2019, which changed the totals slightly; those updated totals are reflected in the text of this Issue Brief.

[x] Throughout this Issue Brief, “school districts” refers to public school districts, public academies and joint maintenance agreements. Public charter schools are not included here.

[xi] Calculation based on data provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant. To see a list of the equalized valuation per pupil by municipality and the state average, see New Hampshire Department of Education, Office of School Finance, Equalized Valuation Per Pupil 2017-2018, December 19, 2018. To estimate the percentage of students that would receive a subsidy if this policy were in place, this Issue Brief uses Average Daily Membership in Residence for 2017-2018 and the Equalized Valuation per Pupil for 2017. Based on those 2017 data, if this subsidy were in place without other restrictions, nearly three out of every four students (73.2 percent) lived in municipalities that would be eligible for this subsidy in 2017-2018. Figures provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant suggest nine fewer municipalities would have less than $1 million in Equalized Property Valuation Per Pupil, yielding an estimate of 67.2 percent of students living in eligible municipalities.

[xii] For more on kindergarten funding in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s November 8, 2017 Common Cents post “Elections Highlight Continuing Questions About Keno Revenue.”

[xiii] For more on the Statewide Education Property Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[xiv] To see a distribution of the aid anticipated on a municipal-level basis, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Education Funding Analysis, Preliminary Estimates – For Discussion Only, 2019-1232h, March 24, 2019. The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant produced updated estimates on April 25, 2019, which changed the totals slightly; those updated totals are reflected in the text of this Issue Brief.

[xv] To see the total estimated distribution of new Adequate Education Aid, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Education Funding Analysis, Preliminary Estimates – For Discussion Only, 2019-1232h, March 24, 2019. The Office of Legislative Budget Assistant also produced updated estimates.

[xvi] For more on the school building aid program, see RSA 198:15-a through RSA 198:15-w.

[xvii] For the requirement that the Education Trust Fund be non-lapsing, see RSA 198:39. To see a recent history of Education Trust Fund deficits, see the Department of Administrative Services, New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018, page 150.

[xviii] For more on the current Interest and Dividends Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[xix] For more on how taxable capital gains are defined in federal law, see the Internal Revenue Service web pages on capital gains and losses (Topic Number 409) and the Sale of Residence – Real Estate Tax Tips.

[xx] See RSA 77-A:4, I for the statute exempting income taxable under RSA 77. See also the fiscal note for House Bill 686 of the 2019 Legislative Session and Elizabeth McNichol, State Taxes on Capital Gains, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 11, 2018.

[xxi] For the data table, see the Tax Policy Center, T18-0231 – Distribution of Long-Term Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2018. Learn the income sources included in expanded cash income at the Tax Policy Center’s web page: Income Measure Used in Distributional Analyses by the Tax Policy Center. Learn more about the federal capital gains tax and the incomes of those historically most likely to realize capital gains from Thomas L. Hungerford, The Economic Effects of Capital Gains Taxation, Congressional Research Service, June 18, 2010.

[xxii] For more information on the Interest and Dividends Tax and the data source for these calculations, see the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, 2018 Annual Report, page 52.

[xxiii] For details on revenue source collections to the General Fund by State fiscal year, see the Department of Administrative Services, State of New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018, page 148.