Limited access to affordable child care creates significant challenges for New Hampshire’s families and economy, and may hinder New Hampshire’s efforts to support a robust workforce.[1] While New Hampshire families requiring child care experienced challenges with availability, affordability, and quality of care before 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges and highlighted the severity of barriers to child care. During the public health emergency, many employees with young children had to work from home alongside their children, reduce their working hours, or drop out of the workforce entirely.[2] Despite the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency announced in May 2023, the challenge of finding and affording high quality child care persists, with recent data suggesting an average of approximately 16,000 Granite Staters a month during the year ending in October 2023 were out of the workforce because they were providing care for children.[3]

Child care is a major household expense for families with children. For New Hampshire families with both an infant and a four-year-old in center-based care in 2022, the total average annual price of tuition was $28,340.[4] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) considers affordable child care to be no more than 7 percent of a family’s household income.[5] A New Hampshire household with children that earned the median family income of $119,983 in 2022 would have needed to spend approximately 24 percent of their income on child care.[6]

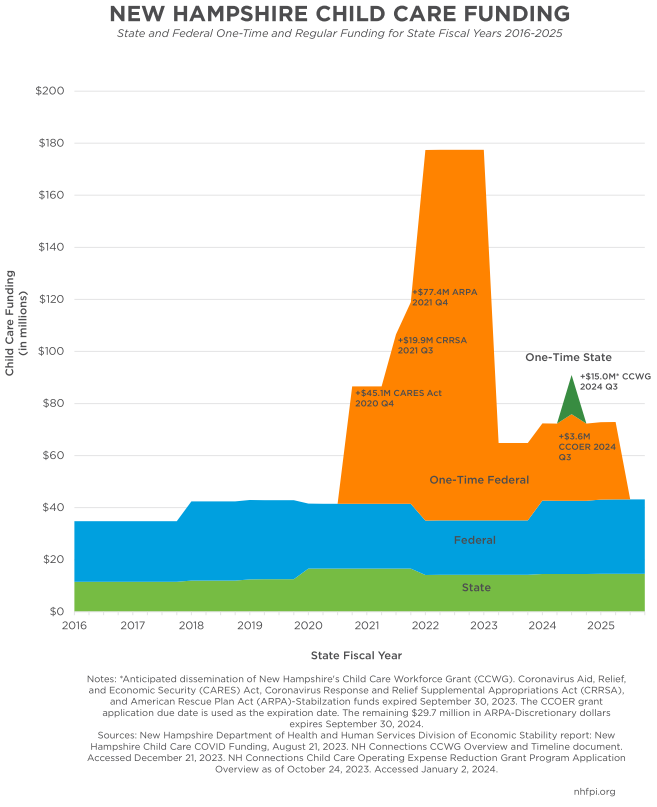

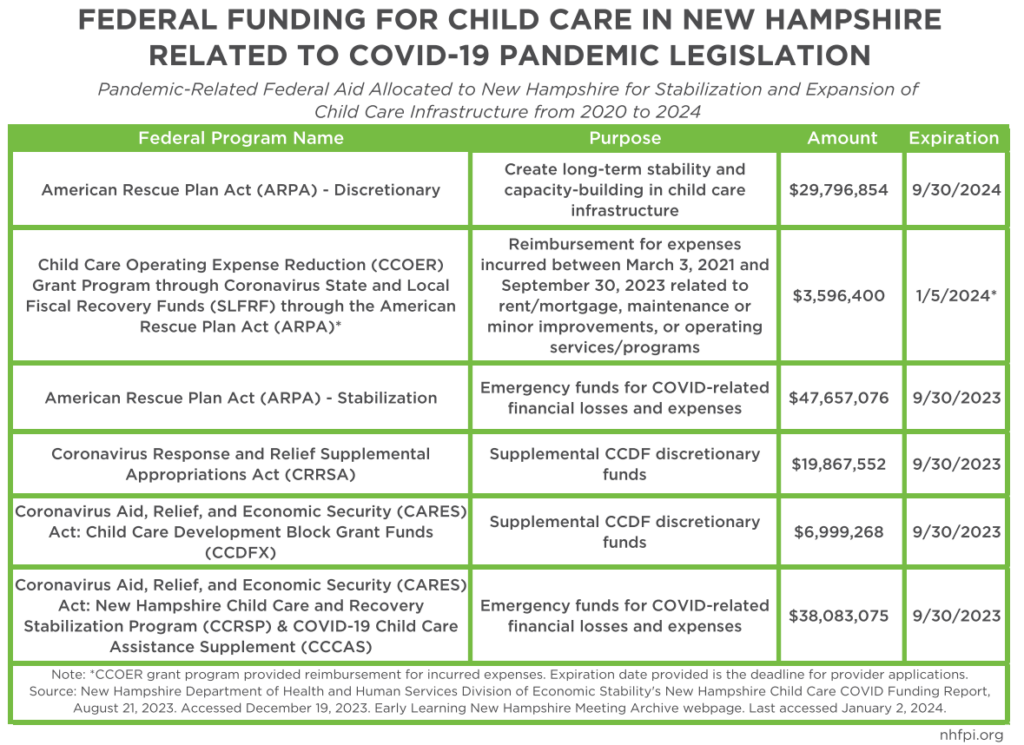

Since State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2016, over $555 million in federal and State funding has been, or is currently being, deployed by the State to support the child care sector.[7] However, $145.9 million of those funds (26 percent) are one-time federal relief dollars associated with the COVID-19 pandemic that have either expired or will expire by September 30, 2024.[8] An additional $15 million (3 percent) of the $555 million are one-time State funds for the child care workforce that will be distributed in SFY 2024.[9] Consistent funding allocations toward the child care infrastructure in New Hampshire may help ensure more long-term stability. As the challenges faced by the child care sector existed well before the pandemic, on-going support is necessary to help ensure high-quality child care is available and affordable to bolster the state’s workforce, equip New Hampshire’s children with pre-academic and socioemotional skills, and grow the Granite State economy.

This Issue Brief summarizes State and federal funding allocated to child care in New Hampshire since 2016, the uses of those funds, and potential sources for additional resources that could be used to support child care in the Granite State going forward.

Standard State and Federal Funding for Child Care

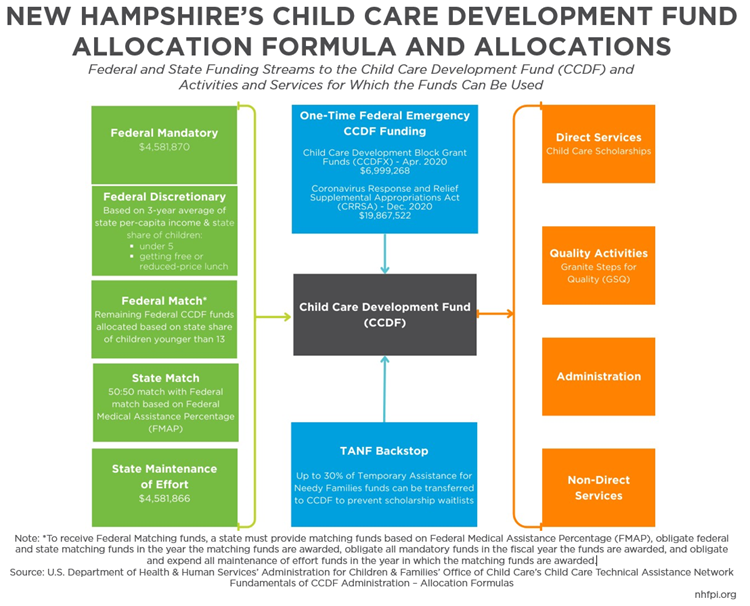

Child care subsidies and infrastructure supports are funded through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), administered by the Federal Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care in partnership with states. The Fund is intended to help families with low incomes afford child care and support child care providers in making the care they provide high-quality.[10] In New Hampshire, the majority of CCDF funds are used to support the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship (NHCCS) program and New Hampshire’s Granite Steps for Quality (GSQ), the State’s Quality Recognition and Improvement System (QRIS) for child care.[11]

The CCDF consists of five funding streams: federal mandatory, federal discretionary, federal matching, State matching, and State maintenance of effort (MOE). Additionally, if a state uses all available CCDF funding, it may use up to 30 percent of funds allocated to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program to ensure there is not a waitlist for the child care subsidy funded by CCDF.[12] The allocation formula for the federal funding streams is derived from a variety of factors. The federal mandatory contribution is 100 percent federally financed and based on funds previously received as part of the now-repealed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) assistance policies. New Hampshire’s federal mandatory contribution is approximately $4.5 million and does not change from year to year. Federal discretionary funding is also 100 percent federally funded and is calculated by determining a state’s share of children under five years old relative to all children in the United States, a state’s share of children receiving free or reduced-priced lunch (FRPL) relative to all children in the United States who are receiving FRPL, and the three-year average state per-capita income. Due to the fluidity of these calculations, the federal discretionary contribution varies year-to-year. Federal matching dollars are the remaining federal CCDF dollars after funds have been set aside for federal administrative support, research, and tribal- and state-level appropriations. These dollars are disseminated based on the state’s share of children under 13 years old compared to the total number of children under 13 in the United States.[13]

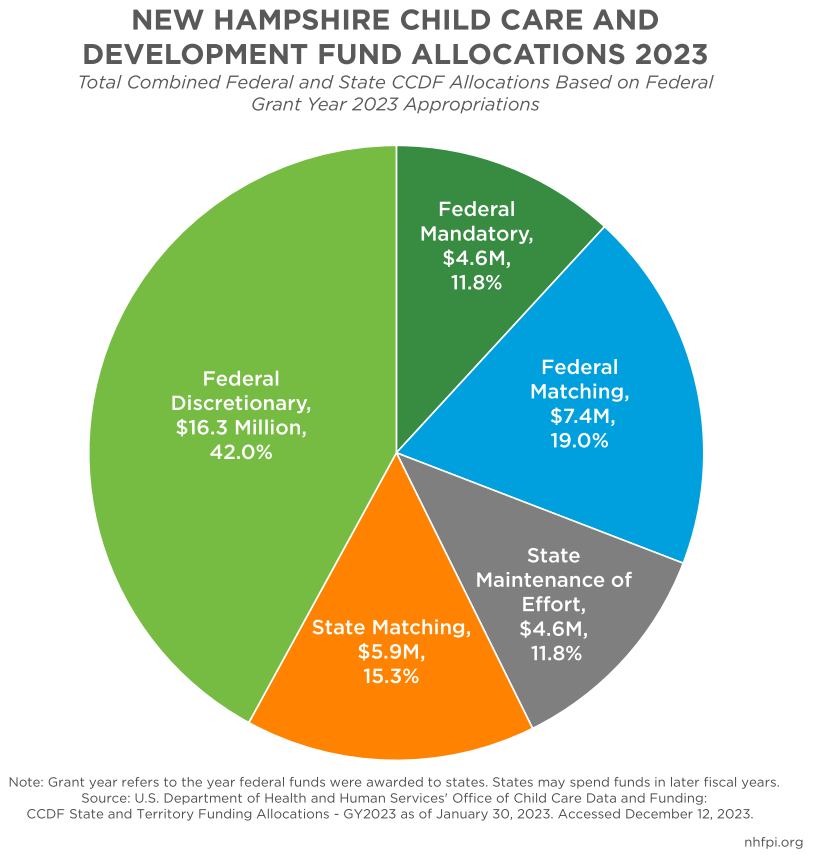

To receive federal-level matching funds, states must provide matching funds based on the Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) rate, primarily used in the Medicaid program, and obligate federal and state matching funds, federal mandatory funds, and state MOE funds all in the year the matching funds are awarded.[14] Additionally, states must spend down their MOE funds prior to receiving federal matching funds.[15] New Hampshire’s MOE funds are approximately $4.6 million and, like the federal mandatory funds, do not change across years because they are also based on the repealed AFDC. The federal government also requires that states allocate 12 percent of CCDF funds toward child care quality initiatives, with 3 percent designated for infant and toddler-focused activities and 9 percent allocated to general child care quality. In 2023, New Hampshire’s CCDF totaled $38,694,772.[16] The State’s MOE accounted for 11.8 percent of that total, while its share of matching funds was 15.3 percent. Federal funds accounted for nearly 72.9 percent of New Hampshire’s CCDF dollars, including federal mandatory funds (11.8 percent), federal matching funds (19.0 percent), and federal discretionary funds (42.0 percent).[17]

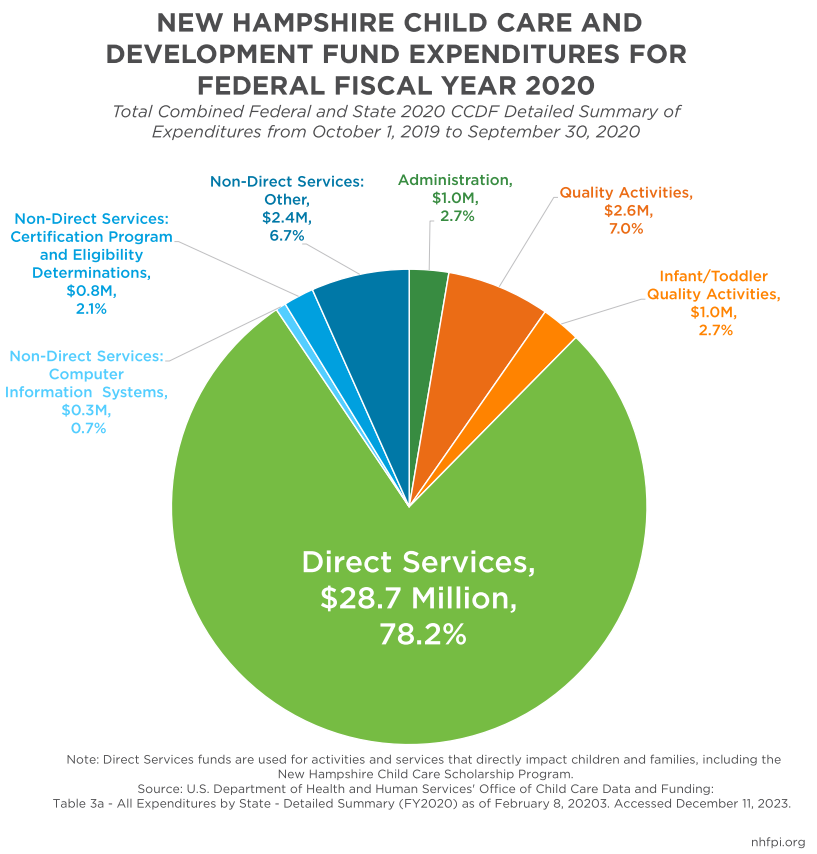

In Federal FY 2020, the most recently published figures with a detailed summary of New Hampshire’s CCDF expenditures, denoted there were approximately $36.7 million in total expenditures. Of this total, 78.2 percent were used for direct child care services, 7.0 percent for quality activities like New Hampshire’s GSQ incentives programs, 2.7 percent for infant/toddler quality activities that increase the supply and quality of care for children under 2 years old, and 2.7 percent for administration of CCDF related funds (this portion is not permitted to exceed five percent of funds, according to federal rules).[18] The remaining 9.4 percent of funds were used for non-direct child care services, including information systems (0.7 percent), certification program and eligibility determinations (2.1 percent), and other non-direct costs including funding for research and evaluation, market rate surveys, and Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) services (6.7 percent).[19]

New Hampshire’s State Budget uses a combination of federal and State funds to support child care. The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) Division of Economic Stability’s (DES) Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaborative (BCDHSC) supports New Hampshire’s child care infrastructure. In the SFYs 2024-2025 New Hampshire State Budget, the Child Care Quality Program and Child Development Operations are 100 percent federally funded.[20] The Child Care Quality Program (GSQ) strives to improve the quality of, and access to, child care in New Hampshire to help ensure school success for participating children.[21] In SFY 2023, this fund received approximately $3.3 million in federal funds, which equated to $75 per licensed capacity child care spot; these funds were used as incentives for providers participating in the GSQ program and supported contracts with a CCR&R agency, after school training, technical assistance, the State higher education system, and training and support to providers to avoid child expulsions in preschool programs.[22] Child Development Operations are allocated $746,895 and $768,917 in federal funds for SFYs 2024 and 2025, respectively, which will provide support for, and administration of, the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program (NHCCSP).[23]

The Child Development Program, which funds NHCCSP, uses both federal dollars and State General Funds to subsidize child care for low- and moderate-income families in order for parents to work, pursue educational or career training opportunities, or receive treatment for mental health or substance use disorders.[24] This fund also supports the salaries and benefits of nine full-time state employees who administer and support NHCCSP. In SFY 2023, the program served nearly 3,000 children per month, with an annual expenditure per child of nearly $10,000, approximately 45 percent of which was funded by the State and 55 percent paid with federal funds.[25]

A portion of CCDF funding is also allocated to the Child Care Licensing Unit within the Office of Legal and Regulatory Services at DHHS to support staff positions for monitoring child care programs and coordinating criminal background checks for child care employees. This Unit ensures providers are complying with safety regulations and supports technical assistance to providers regarding health and safety requirements.[26] Additionally, the State Budget allocates approximately $125,000 per year in SFYs 2024 and 2025 in non-CCDF funds to support a collaboration between the State and the Head Start (HS) and Early Head Start (EHS) programs, which provide federally-funded pre-school and child care with comprehensive support programs for families with low incomes.[27] New Hampshire’s Head Start Collaboration Office is housed within the BCDHSC. HS and EHS, however, are funded through a federal-to-local model, through which funding is provided directly to communities through designated agencies that support HS and EHS providers throughout the state.[28]

One-Time Federal and State Funding

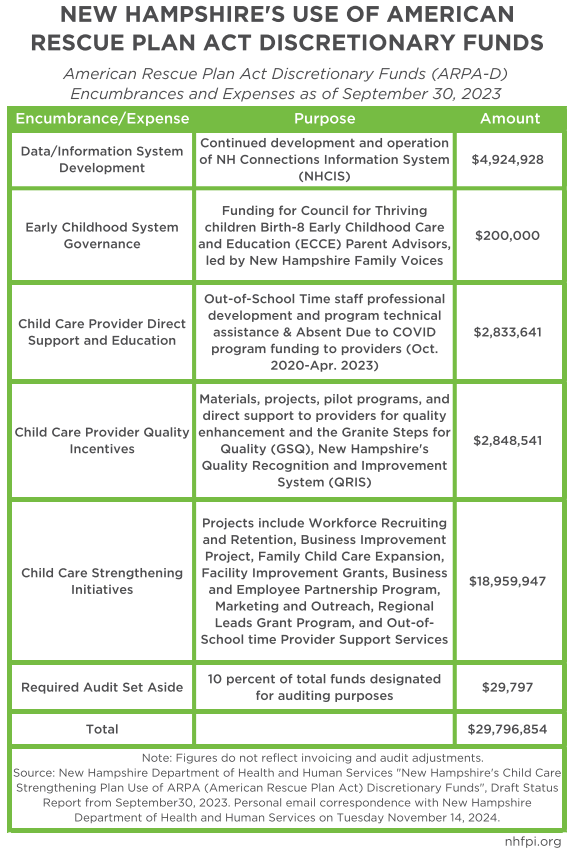

Since March 2020, New Hampshire has received approximately $145.9 million in federal funds to stabilize and expand the Granite State’s child care infrastructure throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.[29] Some of these funds were administered as one-time, emergency grants to child care providers, including the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) – Stabilization funds. Others were divided into different grant programs made available to New Hampshire child care providers, such as the supplemental CCDF discretionary funds. ARPA-Discretionary (ARPA-D) funds, however, are currently allocated among multiple contracts with the intention to strengthen the long-term stability of New Hampshire’s child care infrastructure.[30]

ARPA-D funds are the only dollars still available for spending from federal COVID-19 response legislation and are currently encumbered with, or have been spent on, nine projects. These projects range from contracts to improve individual child care business models, to marketing and outreach to promote initiatives like the expanded eligibility for child care scholarships, to IT and data support for the systems that allow for communication between the DHHS BCDHSC and providers for licensing, quality credentialing, and grant purposes.[31] The plan to disseminate ARPA-D funds was developed over a six-month period in consultations with families, child care providers, advocacy groups, legislators, State agencies, and philanthropists.[32]

The Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program was derived from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (CSLFRF) awarded in 2021. Approximately $3.6 million in federal dollars were designated by the Governor’s Office for Emergency Relief and Recovery (GOFERR) to be used by child care providers for expenses incurred between March 3, 2021 and September 30, 2023 related to rent, mortgage, or lease payments, maintenance and repairs or minor improvements, building or expanding existing playground space, business operating programs or services, or facility enhancements and programing that improved the staff experience.[33]

One-time ARPA-Stabilization funds were intended to be used for activities that would increase availability of child care slots and ended on September 30, 2023. Providers obtained these funds through grant applications to BCDHSC. Of the roughly 700 providers in New Hampshire, 590 received ARPA-Stabilization awards that averaged approximately $81,400 per each child care center and $53,200 per family home provider.[34] The most common use of the temporary funds was to pay for wages and staffing to keep programs open.[35]

The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) supplemental discretionary CCDF appropriations were approved through an Emergency Order from New Hampshire’s Governor and administered to providers through BCDHSC by grant process.[36] The funds could be used for certain enumerated purposes, including helping families pay for child care, paying wages to employees, bolstering policies and processes that reduced the spread of viruses, and supporting provider reporting and monitoring processes. These funds were also used to support the Absent Due to COVID billing program and School Age Child Full-Day billing for NHCCS program providers.[37] The one-time CRRSA CCDF funding expired September 30, 2023.

New Hampshire also received two influxes of funding through the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act: 1) Child Care Development Block Grant Funds (CCDFX) supplemental discretionary funds directly provided to states’ CCDF funds and administered to providers in New Hampshire by BCDHSC through an application process, and 2) flexible federal funds administered through GOFERR to the New Hampshire Child Care Recovery and Stabilization Program (CCRSP) and COVID-19 Child Care Assistance Supplement (CCCAS) program, both of which were disseminated via applications from providers.[38] CCRSP could be used by providers for recouping pandemic lost revenue, supporting pandemic-related program adaptations, paying tuition costs, and bolstering staff professional development.[39] Subsequent CCCAS funds were administered to address additional losses and COVID-19-related expenses to help ensure providers could safely stay open and both recover and stabilize from pandemic related impacts.[40] These one-time funds also expired on September 30, 2023.

New Hampshire’s SFYs 2024-2025 budget allocates a one-time appropriation of $15 million in State General Fund dollars for child care workforce recruitment and retention, with resources to be deployed through the Child Care Workforce Fund (CCWF). These funds will be disseminated based on applications from providers, which were due at the beginning of January 2024; funds are anticipated to be released in the third quarter of SFY 2024.[41]

While approximately $160 million in State and federal one-time funding has been allocated to New Hampshire’s child care infrastructure since 2020, most of this funding was intended to stabilize the industry and replace lost income for child care providers, rather than focus on the long-term success of the Granite State’s child care infrastructure. Only funds from ARPA-D, approximately 18 percent of the one-time federal and State funds allocated since 2020, are meant to bolster the long-term health of the child care sector in New Hampshire; those funds must be used before the end of September 2024. After these additional funding sources are gone, the public finances dedicated to supporting New Hampshire’s child care sector will be reduced to levels similar to the years preceding 2020. Without additional consistent, long-term investments in child care infrastructure, the same challenges will likely continue to impact the child care market, New Hampshire’s workforce, and the overall Granite State economy.

Additional Approaches to Child Care Funding

As the remaining one-time child care funds are spent, continued support for the State’s child care infrastructure depends on additional funding, particularly stable funding.[42] Sources of federal funding, especially those focused on infrastructure development, are available and may be utilized by the State and businesses within its borders to support the child care sector. For example, the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) program application, part of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, requires a workforce development plan that includes a specific child care plan for any direct funding over $150 million, and all applicants are encouraged to submit child care plans to support employees working for CHIPS grantees.[43] Similarly, states and municipalities can prioritize contractor applications that devote project funds to child care in proposed project areas to support employee child care needs. Additionally, municipalities may seek out Community Development Block Grant funds to support child care for employees as part of economic development grant and loans programs.[44]

States can also incorporate child care spending into other workforce initiatives. California allocated $25 million for the Equal Representation in Construction Apprenticeship Grant Program.[45] The program is intended to diversify the building trades field in California by making entry into the profession more accessible for women, people of color, veterans, and at-risk youth. The program allows for grant funds to be spent on direct stipends ($5,000 to pre-apprentices, $10,000 to apprentices) to pay for child care as well as reimbursement for child care, salary for a child care coordinator, or for all costs associated with an onsite child care provider.

Finally, continued collaboration and communication among early child care and education stakeholders within the state is essential to leverage collective resources to help ensure consistent funding is appropriated to support the overall child care infrastructure. An example of such a collaboration occurred within the past five years between the University of New Hampshire’s acquisition of a Preschool Development Grant through the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and recent ARPA-D funding. ESSA funds the Preschool School Development Grant Birth Through Five (PDG B-5), a program intended to support overall child care infrastructure in states and territories through direct services for young children, workforce compensation, quality improvement, needs assessments, and strategic planning.[46] The University of New Hampshire was awarded $26.8 million in PDG B-5 funds from 2020-2022 and an additional $3.9 million in 2023 to fund multiple projects, including several State child care needs assessments, development of a State child care strategic plan, and support for an Early Childhood Regional system that would enhance communication and collaboration among early child care providers, families, and schools to determine needs and infrastructure supports in different areas of the State.[47] Portions of the PDG B-5 grant informed the work supported by current ARPA-D funding, including efforts to expand the number of family child care providers throughout the state, particularly in rural regions.[48]

Conclusion

New Hampshire relies heavily on federal funding to support the state’s child care infrastructure. Since 2016, over 72 percent of the Granite State’s child care infrastructure funding has come from the federal government. More than a quarter of the total funding during this period has been from one-time allocations from federal COVID-19-related legislation that have expired or are set to end in September 2024. With no mechanism to replace the one-time federal funding, New Hampshire may experience continuing, or worsening, child care shortages as these funds expire.

While providing one-time State General Funds for the Child Care Work Force Grant program is a key investment, the child care workforce would likely benefit from consistent, prioritized State funding. Such funding could help New Hampshire providers of all sizes function at full capacity, including in rural areas with more limited workforces and other local resources. Consistent funding could create more child care availability and allow parents to work to enhance family income and savings, as well as to grow the state’s workforce and economy. One national 2021 analysis estimated that New Hampshire households collectively lost between $400 million and $600 million in wages due to unavailable child care. When business and tax revenues were incorporated into the analysis, an estimated $44,110 and $66,816 per unavailable child care slot was lost annually over a projected ten-year period from the time of the initial single-year child care shortage.[49] For New England families, particularly those with low incomes, caring for children at home or relying on a mix of child care arrangements are necessary to be able to afford care.[50] Households with more limited economic resources pay larger portions of their income toward child care, especially people of color who are disproportionately more likely to experience poverty in New Hampshire.[51]

Combining child care sector investments with other federal- and State-funded infrastructure projects is one way New Hampshire could simultaneously prioritize funding for child care with other areas for investments, including housing and transportation. These investments could support workers with different specialties to engage in employment if they choose to do so, rather than caring for a child at home, boosting economic growth and efficiency and enhancing opportunities for Granite State individuals, families, and children.

Endnotes

[1] See NHFPI’s August 2023 Issue Brief, Granite State Workers and Employers Face Rising Costs and Significant Economic Constraints. See also the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s May 2019 publication, High-Quality Early Child Care: A Critical Piece of the Workforce Infrastructure.

[2] For more information on the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the child care sector, see the Carsey School of Public Policy and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s August 2020 publication, COVID-19 Didn’t Create a Child Care Crisis But Hastened and Inflamed It. To learn more about how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted child care and New Hampshire’s workforce, see Econsult Solutions Inc. and the National Center for Children in Poverty’s February 2021 final report, Constraints on New Hampshire’s Workforce Recovery: Impacts from COVID-19, Child Care and Benefit Program Design on Household Labor Market Decisions.

[3] This figure is a NHFPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data, Employment Table 3, from November 2, 2022 to October 30, 2023.

[4] Figures from Child Care Aware’s 2022 Infographic, Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire.

[5] See Federal Register from September 30, 2016, from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families’ Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program Final Rule, p. 3.

[6] See U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 American Community Survey, Table B19125.

[7] NHFPI analysis of HB1 for SFYs 2016-2017, 2018-2019, 2020-2021, 2022-2023, 2024-2025, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Division of Economic Stability’s August 21, 2023 report, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023, and SFYs 2024-2025 HB 2, p. 147.

[8] Figure derived using New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Division of Economic Stability’s August 21, 2023 report, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, and NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023.

[9] NHFPI analysis of Operating Budget Bills for SFYs 2016-2017, 2018-2019, 2020-2021, 2022-2023, 2024-2025, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Division of Economic Stability’s August 21, 2023 report, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023, and SFYs 2024-2025 HB 2, p. 147.

[10] See the Federal Administration for Children and Families’ Office of Child Care’s webpage, What is the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF)? and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration of Children and Families’ Office of Child Care’s Child Care Technical Assistance Network’s Fundamentals of CCDF Administration webpage. Accessed January 2024.

[11] See the federal Office of Child Care’s Table 3A, New Hampshire figures. To learn more about New Hampshire’s Quality Recognition and Improvement System (QRIS), Granite Steps for Quality (GSQ), see New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services March 2023 presentation.

[12] See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families February 19, 2016 Information Memorandum and New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s October 19, 2023 Informational Item prepared for the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee.

[13] See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children & Family’s Office of Child Care’s Child Care Technical Assistance Network’s Fundamentals of CCDF Administration Allocation Formulas. Accessed January 2024.

[14] For more information about the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid, see the Kaiser Family Foundation resource, Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier.

[15] See the State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 New Hampshire DHHS Division of Economic Stability Briefing Book’s Funding Source information under the Child Development Program (4211-2977). Note: CCDF Mandatory and Matching funds were permanently determined by the American Recovery Plan Act of 2021. FMAP rates were temporarily increased during the pandemic beginning on March 18, 2020. The Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) created a transition period of incremental changes in FMAP between April 2023 to December 2023. After December 2023, FMAPs returned to the original rates. See Note 3 on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care’s Grant Year 2023 CCDF Allocations webpage.

[16] See New Hampshire’s figures on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care’s Grant Year 2023 CCDF Allocations webpage. Note: This figure is approximately $4 million less than funds appropriated in SFYs 2022-2023 budget described in HB1. The difference is related to the dates of New Hampshire’s State Fiscal Year and the federal Office of Child Care’s grant year designations for CCDF funds. States may liquidate Federal CCDF funds in a different year than the designated grant year based on when state fiscal years begin and end. For more information, see Note 1 in the Office of Child Care’s CCDF Fiscal Year 2020 State Spending From All Appropriation Years.

[17] See New Hampshire figures on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care’s Grant Year 2023 CCDF Allocations webpage.

[18] See the federal Office of Child Care’s Table 3A, New Hampshire figures. To learn more about New Hampshire’s Quality Recognition and Improvement System (QRIS), Granite Steps for Quality (GSQ), see New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services March 2023 presentation.

[19] See the federal Office of Child Care’s Table 3A, New Hampshire figures. For more examples of non-direct services, see the federal Office of Child Care’s Regulations Regarding Use of CCDF Funds for Research and Evaluation.

[20] See Chapter 106, Laws of 2023 for the Child Care Quality Program (4211-2978) and Child Development Operations (4211-2976) State Budget appropriations.

[21] See NH Connections Quality Care Matters webpage and the State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 NH DHHS Division of Economic Stability Briefing Book’s Child Care Quality (4211-2978)’s Purpose. Note: During the spring and fall of 2022, Granite Steps for Quality replaced New Hampshire’s previous Quality Recognition and Improvement System (QRIS) which had three categories denoting quality: Licensed, Licensed Plus, and Accreditation (for nationally-accredited programs).

[22] See State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 Economic Security Briefing Book’s Financial Summary for Child Care Quality. Note that this figure is derived from all available licensed capacity child care spots, not the number of current spots available, as some providers may not be functioning at full capacity due to staffing shortages. This figure does not include licensed-exempt facilities.

[23] See SFYs 2024-2025 HB1 budgets for Child Development Operations (4211-2976) and New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaborative SFYs 2024-2025 operating budget presentation.

[24] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaborative SFY 2024-2025 operating budget presentation, State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 Economic Security Briefing Book’s Financial Summary and Services Provided information under the Child Development Program (4211-2977), and NH Connection’s NH Child Care Scholarship Program 101 slide deck Approved Activities slides.

[25] See State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 Economic Security Briefing Book’s Financial Summary information under the Child Development Program (4211-2977), and NH Department of Health and Human Services October, 19, 2023 Informational Item prepared for the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. NHFPI original analyses examining contrasting amount of general funds compared to total funds for the program.

[26] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Child Care Licensing webpage, and New Hampshire’s CCDF Plan for Federal Fiscal Years 2022-2024, p. 29, 30, & p. 358.

[27] See SFYs 2024-2025 House Bill 1 budget for the Head Start State Collaborative (4211-2979) and New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services Child Development & Head Start Collaboration webpage. For more information about Head Start, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Head Start: Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center’s Head Start Approach webpage.

[28] For more information about Head Start services in New Hampshire, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Head Start: Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center’s Head Start Center Locator and Head Start Approach webpages.

[29] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s document from August 21, 2023, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding.

[30] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s document from August 21, 2023, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding.

[31] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ June 28, 2023 Status Report, New Hampshire’s Child Care Strengthening Plan Use of ARPA (American Rescue Plan Act) Discretionary Funds.

[32] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ October 2021 ARPA Discretionary Funds Recommendations: Considerations and Opportunities Summary Report.

[33] See NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023 and New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s April 21, 2023 Requested Action item prepared for the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee.

[34] See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care’s document, New Hampshire ARP Child Care Stabilization Fact Sheet.

[35] See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Child Care’s document, New Hampshire ARP Child Care Stabilization Fact Sheet. The list of New Hampshire child care providers can be found NH Connections’ New Hampshire Child Care Search website under “Useful Resources – Download Provider Results”.

[36] See New Hampshire Governor’s February 16, 2021 Emergency Order authorizing acceptance and expending of additional CCDF funds.

[37] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration February 24, 2021 document, State of New Hampshire Planned Use of Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2021 (CRRSA) Funds and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ April 14, 2021 Information Memorandum.

[38] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s document, August 21, 2023, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, NH Connections’ June 1, 2020 document, NH DHHS Announces the New Hampshire Child Care Recovery and Stabilization Program (CCRSP) Funding Opportunity, and NH Connections document, COVID-19 Child Care Assistance Supplement (CCCAS).

[39] See NH Connections’ June 1, 2020 document, NH DHHS Announces the New Hampshire Child Care Recovery and Stabilization Program (CCRSP) Funding Opportunity.

[40] See NH Connections document COVID-19 Child Care Assistance Supplement (CCCAS).

[41] See “CCWG Overview and Timeline” under “Child Care Workforce Grant (CCWG)” on NH Connections New Hampshire Provider Grant Funds website. Accessed December 21, 2023.

[42] See University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy’s March 7, 2023 Research Brief, Child Care Investments and Policies in the Upper Valley, in the Pandemic and Beyond.

[43] See the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology’s CHIPS’ Program Office’s March 27, 2023 guide, Workforce Development Planning Guide: Guidance for CHIPS Incentives Applications. For more information on the CHIPS for American program, see the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology’s CHIPS website.

[44] See the Community Development Finance Authority’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) website.

[45] See the California Department of Industrial Relations’ Division of Apprenticeship Standards’ October 10, 2022 publication, Equal Representation in Construction Apprenticeships (ERiCA) Grant Program Year (PY 2023-2025) Solicitation for Proposals (SFP).

[46] Learn more about the Preschool Development Grant Birth through Five (PDG B-5) on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Early Childhood Development website. Learn more about the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) on the National Education Association’s website.

[47] See the University of New Hampshire’s College of Health and Human Services Preschool Development Grant-Birth through Five (PDG B-5) and Grant Activities webpages.

[48] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ Division of Economic Stability’s Requested Action item from June 13, 2023 prepared for the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Bipartisan Policy Center’s October 2023 report, Rural Child Care Policy Framework.

[49] See the Bipartisan Policy Center’s November 2021 report The Economic Impact of America’s Child Care Gap: The Cost of the Child Care Gap to Parents, Businesses, and Taxpayers.

[50] See University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy’s July 12, 2023 Data Snapshot, New England Households Rely on a Mix of Child Care Arrangements, and July 20, 2023 Data Snapshot, New Englanders’ Use of Child Care Varies by Income, Even Among Working Households.

[51] See NHFPI’s October 13, 2023 Fact Sheet, Child Care in New Hampshire: High Price, Low Supply, September 22, 2023 blog, Latest Census Bureau Data Show Median Household Income Fell Behind Inflation, Tax Credit Expirations Increased Poverty, and December 19, 2023 presentation slide, Poverty Rates Vary By Identity Group.