The New Hampshire State Budget funds important services for Granite State families and children, supporting the infrastructure, education and health services, and public amenities that residents use daily. After an extended process, New Hampshire policymakers finalized a State Budget that increases investments in key areas, including public education and health services. The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021, which provides funding through June 30, 2021, includes significant changes to both appropriations and policies.

Investments and policy changes in health care and social services represented some of the largest alterations from the prior budget. Increases in Medicaid reimbursement rates provide systemic support for health services for those with limited resources and the health care workforce, which has been strained by a lack of available employees. Funding for those with developmental disabilities is boosted to levels designed to eliminate the previous waitlist for services. The State’s system to support Granite Staters in need of mental health services receives significant investments, including resources directed at expanding the capacities of both State and community mental health systems. Children’s mental health is specifically addressed through the expansion of places to recover and the addition of mobile crisis units for rapid responses.

Children are supported through additional investments in education, which are targeted at communities with limited abilities to raise funds locally and with higher concentrations of students from low-income households. Additional funding was appropriated for kindergarten students, helping push the total investment in local public education to be the most significant in a State Budget in two decades. Support for public higher education is also increased, as are other workforce supports designed to address current and future needs. Additionally, more resources are devoted to cities and towns with more students, with those resources deployed to communities with higher proportions of New Hampshire’s children from low-income households.

Significant portions of this aid, including the education and general aid directed at communities with more low-income students and less taxable property value, are one-time appropriations. Although State Budgets may be rewritten every two years, the planned one-time nature of these appropriations means that the challenges faced by school districts, local welfare offices, and property taxpayers may only be addressed in a temporary fashion with this funding. Key appropriations to support Medicaid and affordable housing construction are designed to continue, although additional revenue may be needed to support initiatives in these areas in the future.

The State Budget also alters the taxable incomes included in the business tax bases, conforming with federal tax law, and makes a future business tax rate change contingent on revenues received. These changes are projected to increase revenues relative to prior policies.

This Issue Brief compares the State Budget, approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor in September 2019, to its predecessor passed during the 2017 Legislative Session, and explains important provisions and investments enacted for State Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.[i]

The Topline Numbers

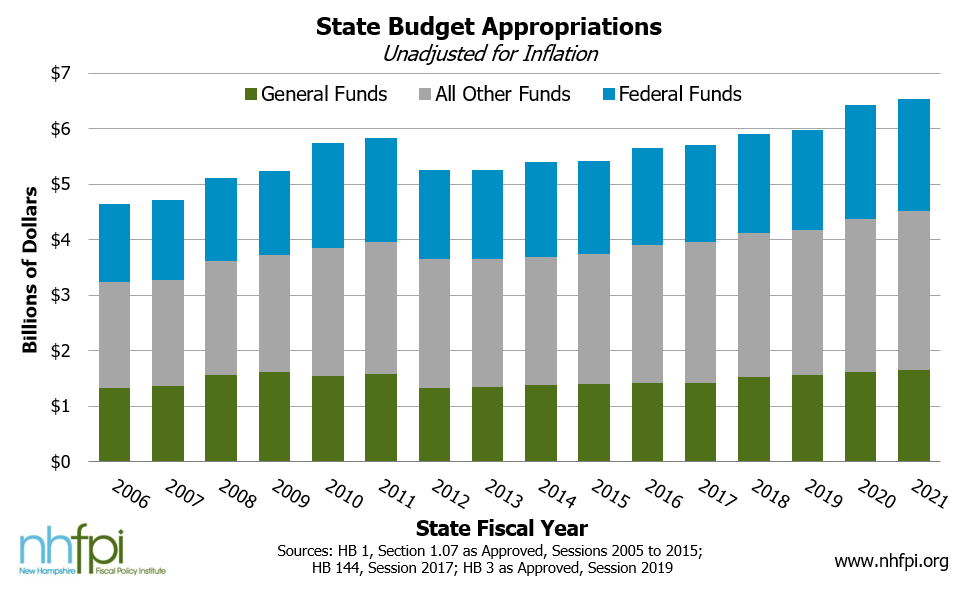

The State operating budget totals approximately $13 billion for the combined expenditures of State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2020 and SFY 2021. The Primary Budget total, the sum of the line items in the operating budget, is approximately $13.36 billion, but State Budget writers removed approximately $402.0 million in previously double-counted transfers between State agencies for information technology services. The State Budget additionally trims $25 million from appropriations to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in a “back-of-the-budget” reduction that is not reflected in the budget line items. However, the State Budget’s Trailer Bill includes more than $200 million in appropriations during SFYs 2020-2021, with language directing those appropriations for specific purposes that have detail beyond the line-item appropriations in the Primary Budget.[ii]

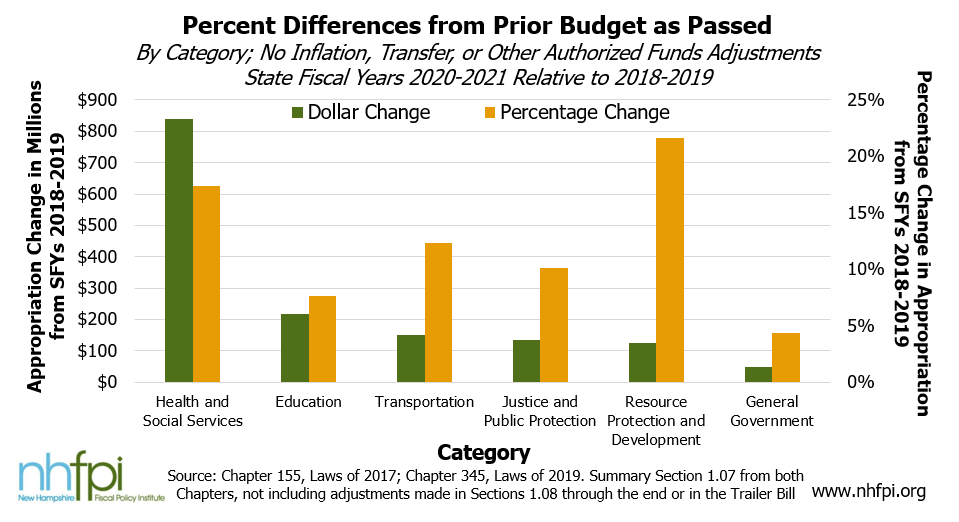

Most expenditures in the State Budget, and all expenditures in the Primary Budget, are assigned to one of six broad categories of government services. Relative to the prior State Budget as passed, the new budget directs most of the increase in dollars to the area of Health and Social Services, and includes significant new spending in federal funds, such as those targeted at supporting developmental services and responding to the opioid crisis. The next largest area of investment is Education, which increases by $216.2 million (7.6 percent), unadjusted for inflation, over the prior two-year State Budget as passed in 2017. Much of this increase is accounted for by a $139.0 million increase in aid to public school districts for student education, increases in support for higher education, and several other initiatives. Investments in Transportation amounted to an additional $149.7 million in the category, or a 12.3 percent increase when compared to the prior two-year budget and not adjusting for inflation. Resource Protection and Development increased more in percentage terms than any other category, with a 21.6 percent increase, but a significant portion of that increase was due to including a major water infrastructure-related fund in the State Budget that was previously operating but accounted for elsewhere.

Public Education and Workforce Training

With an unemployment rate that has been below three percent since December 2015 and demographic trends that suggest a relatively limited supply of working-age individuals in the future, bolstering New Hampshire’s workforce through training, retention, and attraction of workers and residents will be important to help sustain a strong state economy.[iii] Education can increase the economic and social mobility of children and adults, and public policy can help increase access to equitable educational opportunities for all age groups.

Local Public Education

The State Budget takes key steps to alleviate some of the disparities in resources available to fund local public education in New Hampshire. Approximately 61 percent of local public education funding stems from local property taxes. Another approximately 11 percent comes from the Statewide Education Property Tax, which is as an additional local education property tax that the State requires local governments to levy, with the revenue raised and retained locally.[iv] Local property tax bases are critical for funding local public education, and there are significant disparities in those property tax bases between communities.[v] The SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget made appropriations that begin to contribute to more equitable opportunities with increased investments in communities with less property value and more students from households with low-incomes. However, the investments will not eliminate the disparities and include key components that are only funded with one-time appropriations.

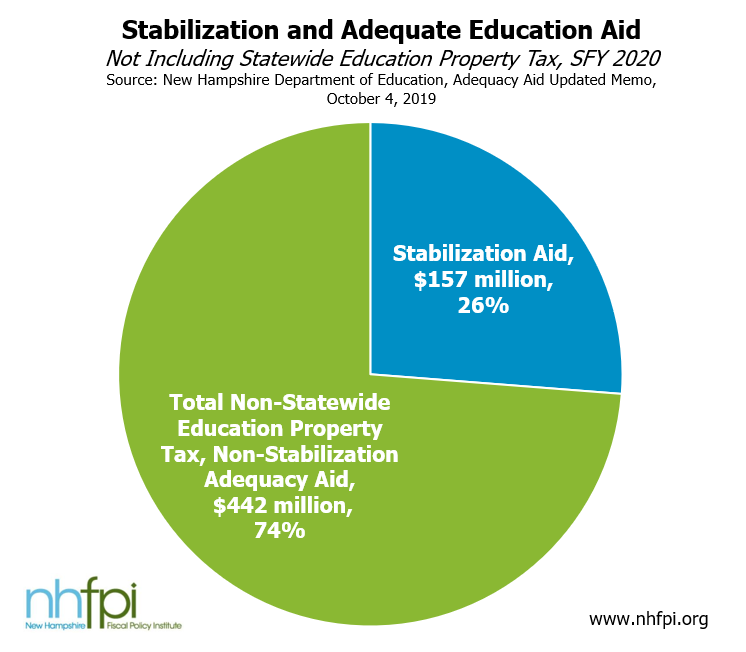

In total, the State Budget appropriates approximately $139 million more in Adequate Education Aid than would have been allocated under prior policy during the biennium.[vi] While that is relative to a total of approximately $962 million in Adequate Education Aid appropriated in SFY 2020 and $1,024 million in SFY 2021, as well as relative to $3,159 million in total expenditures for school districts during the 2017-2018 school year, it will be the most significant increase in State Adequate Education Aid since the creation of Adequate Education Aid in SFY 2000.[vii]

The $139 million increase has several key components, some of which are permanent changes and some of which are temporary. The most significant permanent changes include boosting Stabilization Grants and expanding aid for full-day kindergarten students.

Stabilization Grants are an addition to the Adequate Education Aid formula. They were created following the last major revision to the formula, which took effect in SFY 2012. These Stabilization Grants were designed to ensure no communities would receive lower funding levels than received under the prior formula’s calculations. Between SFYs 2012 and 2016, the Stabilization Grants remained at the same level, going to the communities that were held harmless by the SFY 2012 change in the same dollar amounts. However, State policymakers required Stabilization Grants to decline by 4 percent of their original value per year beginning in SFY 2017; the total value of these Grants had dropped to 88 percent of the SFY 2016 total by SFY 2019. The SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget restores the Stabilization Grants back to their original SFY 2012 amounts for nearly all communities, excluding those municipalities with zero students or those that raise excess revenue through the Statewide Education Property Tax, and retains those increased Stabilization Grants at their SFY 2012 amounts for each subsequent fiscal year. Stabilization Grants generally support communities with relatively small property tax bases per student and relatively lower incomes when the Grants were calculated.[viii] The increase in Stabilization Grants boosts funding for local public education by $56.6 million relative to what was projected under prior law.

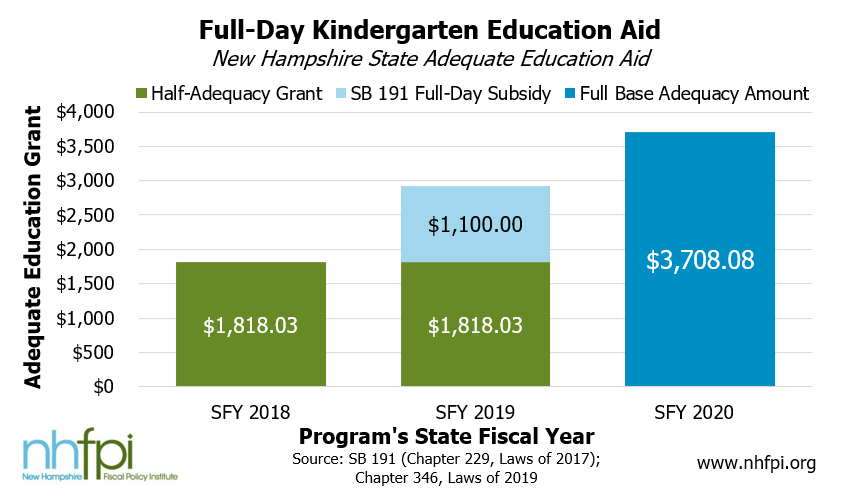

The State Budget also adds aid for full-day kindergarten students with a permanent change to the Adequate Education Aid formula. The State previously funded kindergarten students at half-day levels, or with half of the base Adequate Education Aid grant provided for students in grades 1 to 12, regardless of whether the kindergarten students were in a half-day or full-day program. The full amount of the base-level Adequate Education Grant for SFY 2020 is $3,708.08 per student in grades 1 through 12, and is adjusted for inflation biennially.[ix] In SFY 2019, an additional grant of $1,100 was added for full-day kindergarten students, funded with revenue generated by Keno gaming and closing the gap between the half-day grant and the full base-level grant.[x] The State Budget agreement expands the Adequate Education Aid for kindergarten to the same levels appropriated for students in grades 1 to 12 during SFY 2020 and every year thereafter.

Although approximately $82.4 million in appropriations for additional Adequate Education Aid are not explicitly one-time, the State Budget creates a special account for $62.5 million in targeted appropriations to be deployed only in SFY 2021. This $62.5 million appropriation will be sent to communities based on two different formulas that are one-time additions to the Adequate Education Aid formula.

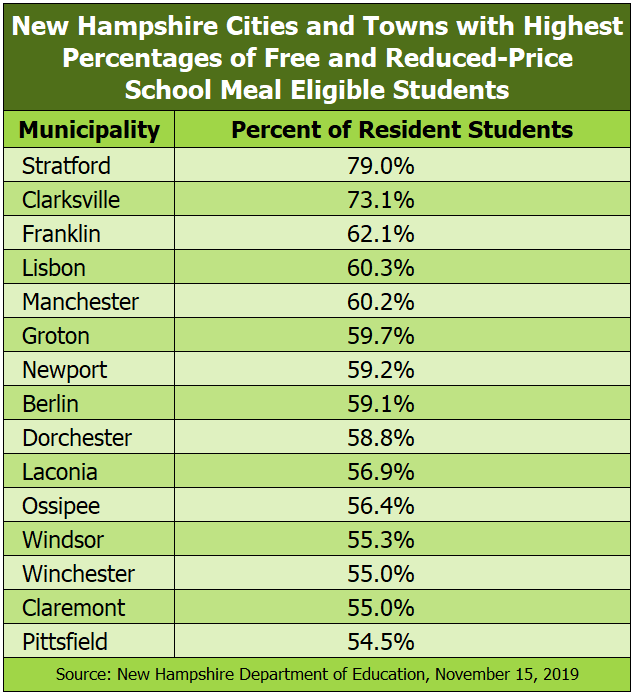

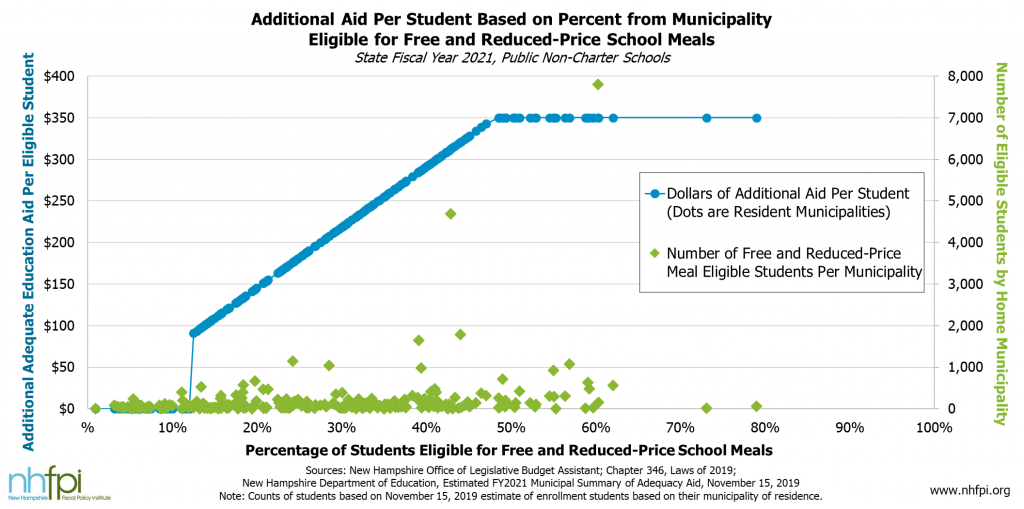

The first additions will be sent based on the proportion of a municipality’s resident students that are eligible for free and reduced-price school meals. To be eligible, these students generally must come from households with incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $39,461 per year for a family of three in 2019.[xi] The baseline Adequate Education Aid funding formula includes a per student grant for free and reduced-price meal students, but the State Budget adds a layer of aid based on the concentration of these students that are residents of a municipality for SFY 2021. In municipalities in which the concentration of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals is below 12 percent, no additional aid is appropriated. For communities with concentrations of at least 12 percent but less than 48 percent, additional appropriations of at least $87.50 and up to $350 per eligible student, increasing on a sliding scale, would be allocated to communities. For those with 48 percent or more students eligible for free or reduced-price meals, an additional $350 per eligible student would be appropriated. This new formula will send more aid for communities that are home to approximately 78 percent of all students statewide and over 94 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, according to the latest data available from the New Hampshire Department of Education.[xii]

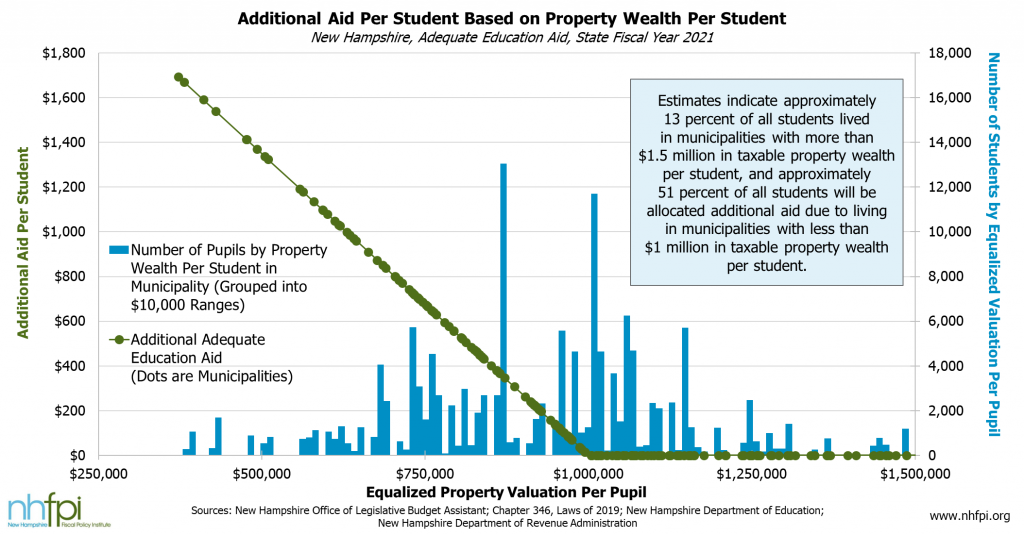

The second component is also based on a sliding scale, with this aid determined by taxable property value per student, formally measured as Equalized Valuation Per Pupil (EVPP). This formula targets aid at municipalities with smaller tax bases per student, which aims to address the disparity between the amount a municipality with high property values and few students can provide in funding for each student’s education relative to those with lower property values and many students. In this one-time appropriation, additional aid is allocated to communities with less than $1,000,000 in taxable property value per student. The smaller the property tax base per student, the higher the additional funding provided per student, rising from $0 to a maximum of $1,750 for municipalities with $350,000 in taxable property value per student or less. About 51 percent of students statewide would be appropriated additional aid under this one-time addition to Adequate Education Aid, based on the most recent data available from the New Hampshire Department of Education.[xiii]

Beyond Adequate Education Aid, the State Budget also boosted support for the traditional School Building Aid program. This $7.0 million increase over previously-committed funding levels enables support for only the next three new projects in the queue. Prior law would have continued the suspension of adding new projects to the program.[xiv] Tuition and transportation aid to support students attending career and technical education programs received an approximately $3.2 million increase in appropriations. Also appropriated is a $17.0 million increase in Special Education Aid over the prior State Budget for particularly high need students and beyond the amounts appropriated in the Adequate Education Aid formula.

Related to other education aid, the State Budget permits the Department of Education to retain three percent of the total annual appropriation to the Public School Infrastructure Fund to administer the program for the disbursement of funds. This program was created as part of the 2017 State Budget process to provide grants to school districts, with a focus on improving school safety and supported with surplus funds. The State Budget amends the program to specifically include supporting Americans with Disabilities Act compliance as an applicable use.

Language incorporated into statute with the passage of the State Budget requires the Department of Education to request the funding necessary to ensure children eligible for free and reduced-price meals at school are provided with free breakfast. The new law incorporates updated references to federal law and increased reimbursements to schools for students eligible for reduced-price meals, but not free meals, under the federal guidelines.

The State Budget also establishes the Commission to Study School Funding. Statute requires this Commission include four members of the House of Representatives, two members of the Senate, one gubernatorial appointee, six members of the public appointed by legislative leadership, and three members appointed by the chairperson of the Commission once the chairperson is elected. The Commission is required to review the education funding formula and make recommendations to ensure uniform and equitable design; determine whether the school funding formula complies with court decisions mandating the opportunity for an adequate education, and with a revenue source that is uniform across the state; identify trends and disparities in student performance; re-establish baseline costs for an opportunity for an adequate education; study property taxation by class of property in a community; study special education funding; and other policy issues. The Commission is provided a $500,000 appropriation to employ independent school finance experts. The Commission must produce an initial report nine months after its first meeting, with a subsequent report completed on or before September 1, 2020.

Higher Education

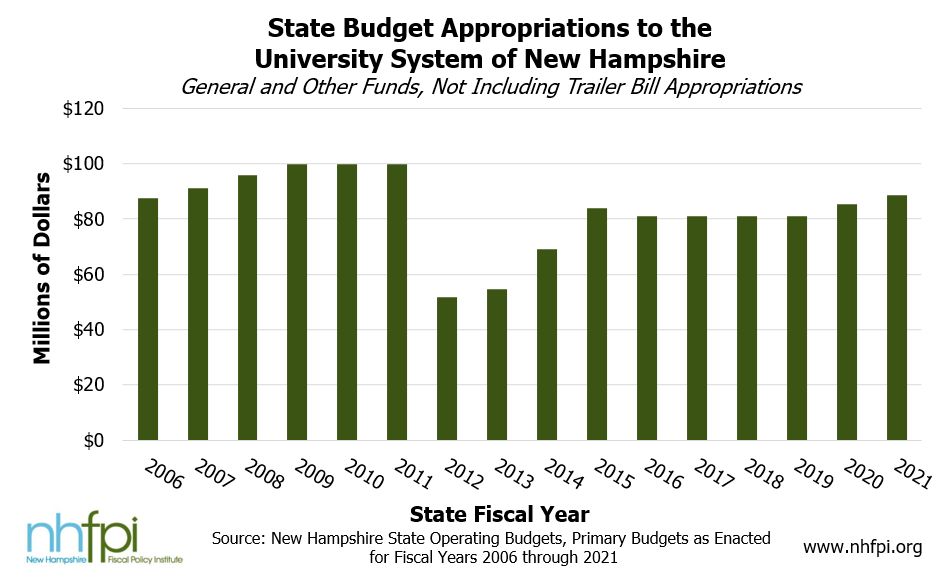

The State Budget provides an increase in general operating support to the University System of New Hampshire for the first time in five fiscal years, and the highest level of State Budget funding since SFY 2011. The new State Budget appropriates an additional $12 million over the biennium to the University System relative to the flat-funded amount in the prior State Budget. The University System also received a one-time appropriation of $9 million specifically to support nursing programs, including acute care and psychiatric mental health specializations, as well as occupational therapy and speech and language pathology programs.

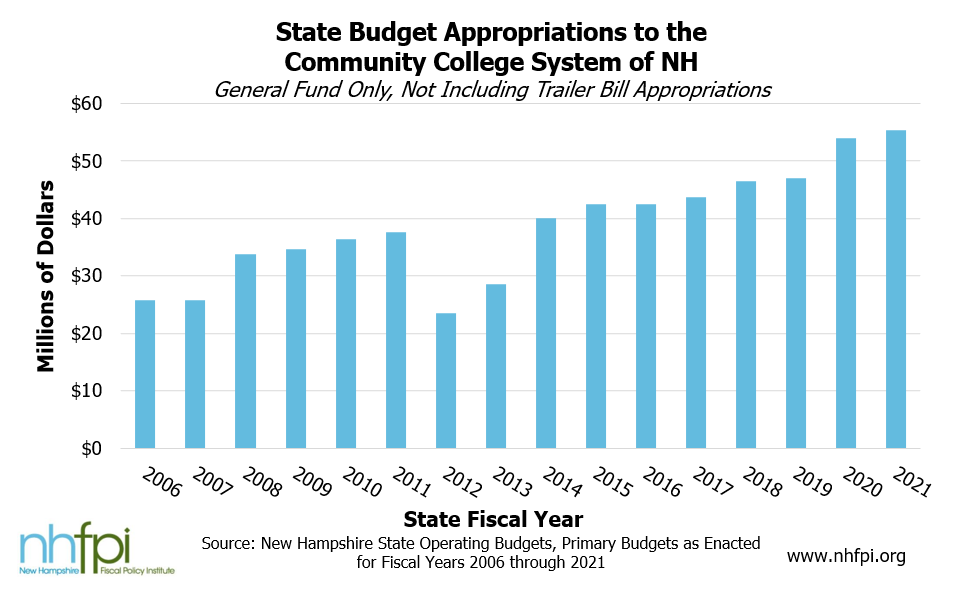

The State Budget continues to increase support for the Community College System of New Hampshire, which receives less support overall than the University System but has been appropriated more incremental increases in each recent State Budget. The new State Budget increases operating support for the Community College System by $10 million over the biennium. The State Budget also appropriates a nonlapsing additional amount of $3.2 million, approximately equivalent to the amount needed to support information technology improvements identified in the Governor’s budget proposal.

Also included in the State Budget’s Trailer Bill is statute establishing the “Finish Line New Hampshire” program within the Community College System to support students over 25 years old to complete degrees in fields where graduates are in high demand, based on labor market and employment information. The Community College System is tasked with determining the details of this program’s administration.

The administration of the Governor’s Scholarship Program is transferred from the Governor’s Office of Strategic Initiatives to the College Tuition Savings Plan Advisory Commission. The Scholarship Program is funded at $3 million per year, less than the $5 million per year authorized under the prior State Budget. The Governor’s Scholarship Program, as defined by statute, provides scholarships of up to $2,000 per year, depending in part on student grade point average, to students who are first-year, full-time, Pell Grant-eligible students and are New Hampshire residents. These resident students must be attending a public or approved private non-profit post-secondary institution in the state and meet certain other requirements.

Other Workforce Training Programs and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

The State Budget incorporates significant policy frameworks for, and amendments to, programs focused on job training and work readiness. Incorporating components of separate legislation, the budget’s language focuses on workforce training generally, and on programs specifically targeted at helping workers with low incomes and expanding the health care workforce.

Incorporating certain language from Senate Bill 2, also known as the “Granite State Jobs Act of 2019,” the State Budget establishes the State’s Job Training Program within New Hampshire Employment Security, transferred from the Department of Business and Economic Affairs. This Job Training Program is focused on individuals not otherwise eligible for state or federal job training programs. It aims to provide child care and transportation assistance to income-eligible individuals who are determined to need that support to successfully compete for career opportunities. The legislation also provides additional funding to the existing WorkReadyNH program, certificate and apprentice programs, marketing of workforce development issues, and recruitment for populations with higher than average unemployment. These efforts are funded through a newly-established Training Fund, which will receive no more than $500,000 annually. The State Budget also appropriates $200,000 during the biennium to support education and acceleration programs within non-profit business technology incubators.

Relative to low-income workers, the State Budget changes the Granite Workforce program to reduce the potential fiscal strain on available Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funding. The Granite Workforce program, which operates as part of the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, New Hampshire’s version of expanded Medicaid, requires that households have incomes of 138 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or less to enroll; however, incomes can potentially rise up to 250 percent of the federal poverty guidelines before the household is disenrolled.[xv] The program subsidizes employers who, after three months of employment of a Granite Advantage enrollee, receive a subsidy of up to $2,000, and receive another subsidy of up to $2,000 after nine months of employment. The Granite Workforce program also makes referrals for job training and educational opportunities for enrollees as needed, with a focus on areas with high levels of need for workers in the state.

The new language also requires that the Granite Workforce program be terminated if TANF reserve funds drop below $5 million. TANF funds are provided through block grants of about $38.4 million per year from the federal government. TANF reserves are particularly important during times of unforeseen need, such as economic recessions, to provide temporary assistance to families who lose income. The estimated balance of the TANF reserve was $70.1 million at the end of SFY 2017, but was projected to fall to $35.6 million by the end of SFY 2019, as expanded additional benefits and appropriations of TANF dollars to other programs have drawn on the reserve. Several earlier iterations of the State Budget would have resulted in the complete depletion of TANF reserves, but the Legislature’s final version of the State Budget projected a remaining balance of $13.5 million, and neither the subsidy or stopgap provisions of the Legislature’s version were altered in the final State Budget agreement.[xvi]

Specifically related to the health care workforce, the State Budget appropriates a nonlapsing $6.5 million to the State Loan Repayment Program, which provides funding for educational loans to certain health care professionals who agree to work in identified underserved areas of New Hampshire for multiple years, depending on aspects of the professional’s employment.[xvii] These funding and policy changes include establishing two new positions and requiring that a set portion be expended by clinicians solely to deliver mental health and substance use disorder treatment services in Carroll, Cheshire, and Coos counties.

The State Budget also appropriates $500,000 to Granite State Independent Living to support a training program, and establishes training requirements relative to direct care staff working in certain residential facilities and community-based services for those with dementia.

Health and Human Services

The State Budget significantly expands public and individual health services and supports for those with resource challenges and limited means. Funding appropriated to the DHHS and policy changes regarding these programs make substantial impacts on services for Granite Staters; these changes include incorporating and funding proposals from separate pieces of legislation considered during the 2019 Legislative Session. Significant increases in funding for Medicaid, a health coverage program helping approximately 175,000 Granite Staters with low incomes obtain access to health care, provide critical systemic support.[xviii] Efforts to invest in the mental health care and substance use disorder care infrastructure are also key responses to ongoing crises.

Medicaid Reimbursement Rates

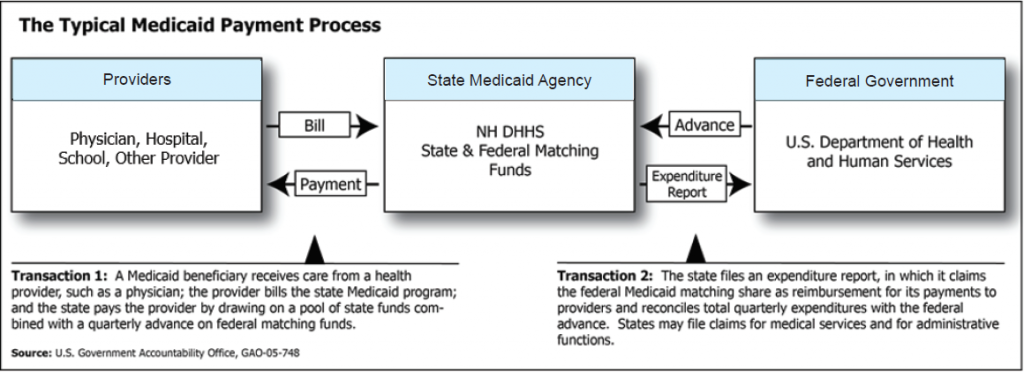

The State Budget increases Medicaid reimbursement rates for nearly all providers by 3.1 percent starting January 1, 2020 and an additional 3.1 percent starting January 1, 2021. Medicaid reimbursements are the dollars the State and federal governments, which split the costs of Medicaid-funded care provided in New Hampshire, pay to Medicaid providers for their services. Increased funding for Medicaid reimbursements may help to make providing health care services to Medicaid patients more economically viable for provider organizations and help them hire additional staff to address unmet needs. To boost Medicaid reimbursement rates, the new State Budget appropriates an additional $31 million in State funds, to be matched with a higher amount of federal funds due to more favorable match rates in certain key parts of the Medicaid program, such as the Granite Advantage program’s 90 percent match rate beginning in 2020.[xix]

The Medicaid services not included in the successive 3.1 percent increases are inpatient-only substance use disorder treatment services. However, the State Budget appropriated $8 million in State funds specifically for mental health and substance use disorder inpatient and outpatient services. The State Budget also appropriated approximately $1.7 million in State funds for designated receiving facility beds, contingent upon the expansion of space at hospital facilities to include at least eight more designated receiving facility beds.

Language in the State Budget also establishes a legislative study committee to examine disparities for case management reimbursement rates in home and community-based Medicaid waiver services, including developmental services, acquired brain disorder services, in-home supports, and Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver services designed to provide supports to those eligible for nursing-home levels of care in their houses and communities. The State Budget also suspends presumptive eligibility for home and community-based services during the biennium.

Expanded Medicaid Funding Structure

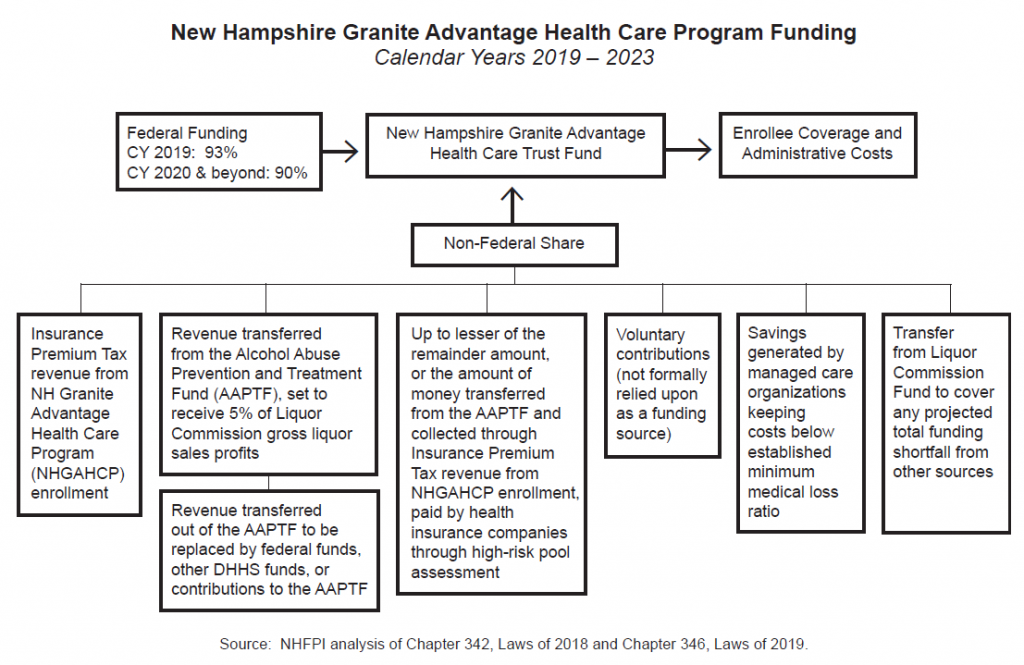

The State Budget alters the funding structure for the Granite Advantage portion of Medicaid, which was at risk of a funding shortfall due to caps on contributions from certain sources imposed by the prior funding structure.[xx] This alteration permits the Granite Advantage Health Care Trust Fund to draw directly from Liquor Commission Fund, which is where gross revenues from the Liquor Commission are first deposited, when the Trust Fund is projected to have a shortfall.

Developmental Services Medicaid Funding and Policy Changes

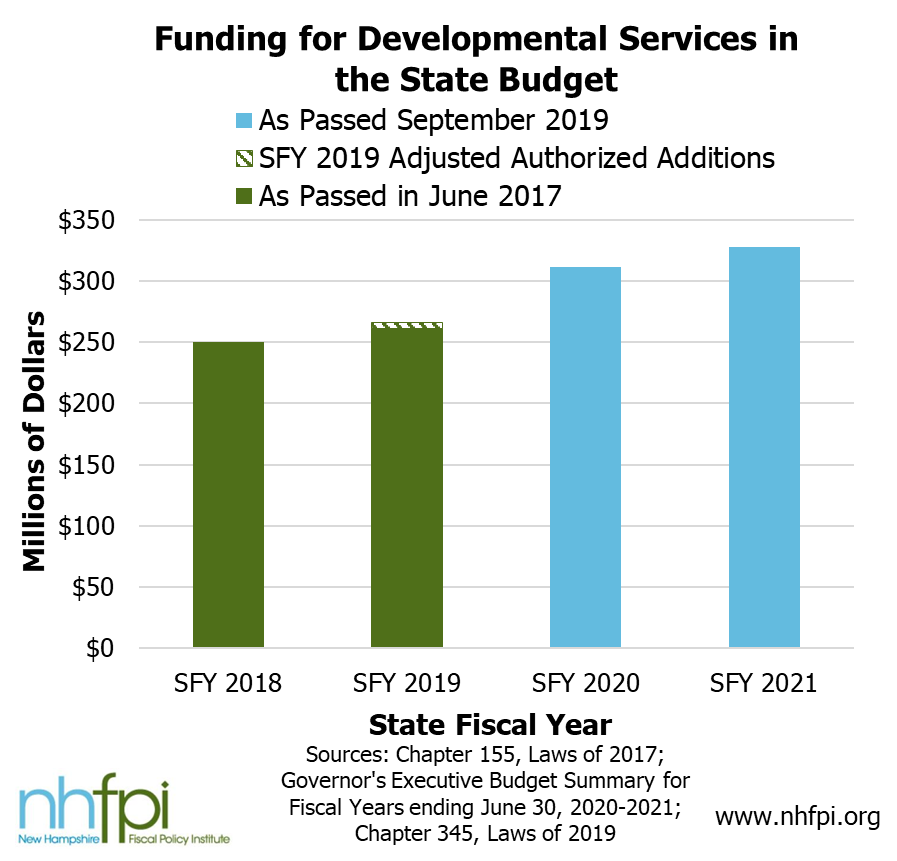

Developmental disability services receive a substantial funding increase in the new State Budget, which is aimed at providing services to all individuals on the waitlist for those services. Relative to the prior biennium, the State Budget appropriates $127.8 million more, in both federal and State funding, for developmental services, primarily delivered through the Area Agency system.

The State Budget establishes a nonlapsing Developmental Services Fund and a separate nonlapsing Acquired Brain Disorder Services fund, which will permit funding to be carried forward from year-to-year without interruption. Statute included in the State Budget also requires the Governor’s Commission on Disability to analyze the State’s system for supporting those with developmental disabilities and recommend reforms and improvements, with a report due by February 2020.

Medicaid Dental, Managed Care, and Housing Services

The State Budget requires the DHHS to create a plan for adding adult dental benefits to Medicaid, with all required changes to State law to be identified by January 2020. The adult dental benefit must be available by April 1, 2021. The State Budget appropriates $500,000 in SFY 2021 to support this benefit, and managed care companies would be required to include it in their plans. The State Budget also appears to remove the requirement that all Medicaid enrollees be eventually enrolled in managed care plans.

The State Budget requires the DHHS to request a waiver from the federal government, or submit an amendment to the State Medicaid Plan to the federal government, to create a State Medicaid benefit for supportive housing services. Medicaid is generally prohibited from paying for housing.

Services for Children and Families

Through both separate pieces of legislation and the State Budget, funding for an additional 57 child protective services workers was appropriated and explicitly directed to be used for no other purpose. The State Budget also recognized and specifically dedicated the appropriations for hiring 20 additional child protective service supervisors during the biennium.[xxi]

The State Budget establishes and funds, in coordination with separately-passed legislation, changes to child welfare supports. The new law requires the DHHS to expend a specific percentage, which increases over time, of funding for children’s behavioral health services on evidence-based practices. In a significant expansion of services, the State Budget funds the addition of mobile crisis response and stabilization for those under age 21 in the state, with response times of no more than one hour statewide. The new statute also requires the establishment of a clearinghouse of information for families seeking information regarding children’s behavioral health services, the formation of a resource center for children’s behavioral health to support the DHHS and service providers with training and technical assistance, the creation of a care management entity at the DHHS to coordinate services for children with more complex needs, and permits courts to, in certain circumstances, refer children to the care of the DHHS’s care management entity. Children being considered for placement outside the home must have a written clinical assessment and a written plan for discharge from treatment programs, and children with severe emotional disturbances or other behavioral health disorders shall, with the consent of the children and their families, be referred to the DHHS’s care management entity. To fund these provisions for child services, the State Budget and accompanying legislation set aside $19.2 million during the biennium.[xxii]

The State Budget establishes a specialized medical evaluation program for abused children, which would permit child protective services workers to have access to health care professionals experienced in caring for these children. Designated health care providers would also be trained to respond to initial signs of child neglect and sexual and physical abuse.

The State Budget funds additional services and efforts targeted toward supporting children, including:

- an Assistant Child Advocate position

- positions to support lead testing procedures, while also establishing the Lead Paint Hazard Remediation Fund

- $900,000 for existing supervised visitation centers during the biennium

- $600,000 for juvenile diversion programs, particularly at the municipal, county, and non-governmental levels

- $500,000 to study pediatric cancer

- $500,000 during the biennium to the Internet Crimes Against Children Fund

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and Federal Grant Replacement Funding

The State Budget makes alterations to the services drawing from the TANF reserve fund balance. The balance was projected to be $13.5 million as of the end of SFY 2021. The estimated balance of the TANF reserve was $70.1 million at the end of SFY 2017, but was projected to fall to $35.6 million by the end of SFY 2019, as additional benefits and appropriations of TANF dollars to other programs have drawn on the reserve. TANF funds are provided through block grants of about $38.4 million per year from the federal government. TANF reserves are particularly important during times of unforeseen need, such as economic recessions, to provide temporary assistance to families who lose income.[xxiii]

The State Budget requires the DHHS to develop a plan to close the “cliff effect.” The cliff effect occurs when individuals or families on a public assistance program have an increase in income, such as from a new job, or another change in their status that makes them no longer eligible for a program, and results in a sudden end to benefits and a reduced overall income for those individuals or families. The State Budget also requires the DHHS to create a “benefits cliff calculator” to measure the effects of increased income on individuals, and form a working group to report policy recommendations, with an initial report due by March 2020 and subsequent reports quarterly throughout the biennium. However, the State Budget appropriated only $1 in each year of the biennium for the development and implementation of this plan.

The State Budget also offsets funding withheld by the federal government for family planning services, appropriating about $3.2 million more than the prior budget in State General Funds.

Services for Older Adults

The State Budget establishes a Medicaid for Older Adults with Disabilities Work Incentive Program. This program, which requires federal approval before it can receive federal funding through Medicaid, would help ensure long-term supports for workers over age 64 with disabilities who have limited incomes. The program would operate in a similar manner to the state’s existing Medicaid for Employed Adults with Disabilities program.

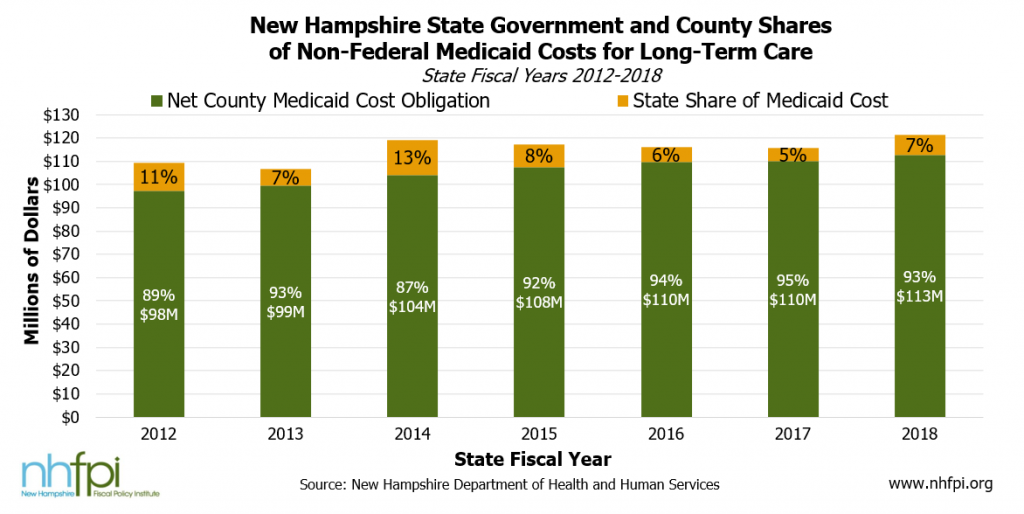

The State Budget increases the amount counties may be billed relative to long-term supports and services delivered via Medicaid to adults from each of the counties. These charges, which include payments for nursing home and Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver services, were adjusted to limit the increased amount owed by counties to three percent.[xxiv] The county obligations for these services, which have increased over time, can put upward pressure on county property taxes.[xxv]

Language in the State Budget also requires the DHHS to raise the income eligibility for adult clients under the Social Services Block Grant program each January to reflect cost of living increases in Social Security benefits. This provision only applies to the SFYs 2020-2021 budget biennium, and must be consistent with federal laws and regulations relative to the Social Services Block Grant program.

The State Budget also appropriates:

- an additional $3.2 million per year for nursing services above the SFY 2019 appropriation, including $2 million in State and federal funds for nursing services for adults with disabilities or who require a skilled nursing facility, and for certain children

- $2 million to establish a pilot program for pharmaceuticals for adults age 65 and older who reach a gap in standard Medicare coverage, with funding available for the first 1,000 adults who apply and have household incomes of 250 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or less

- $1.5 million to fund the congregate housing program

- $200,000 to support the foster grandparent program

Mental Health Services

The State Budget makes significant investments in both the physical infrastructure and the community-based services to support mental health needs in the State. One-time investments in physical infrastructure include $8.75 million for a 25-bed secure psychiatric hospital, which will be operated by the DHHS and explicitly not contracted out to a private or for-profit prison company for construction or operation, and a $5 million appropriation for construction and operation of a separate psychiatric treatment facility specifically for children. The State Budget also provides $4 million to repurpose the children’s section of New Hampshire Hospital to support up to 48 adult beds.

Aside from facility construction or renovation, the State Budget appropriates $5 million in nonlapsing funds for 40 transitional housing beds for forensic patients or those with complex behavioral health conditions, including those transitioning from New Hampshire Hospital. These supports must be operational by June 2021, and funding would be conditional on a plan to be presented to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. The plan for construction of these beds is required by January 2020.

Additionally, the State Budget allocates $750,000 to provide due process for involuntary admissions patients in hospital emergency rooms, to the extent costs are not covered by insurance carriers and requiring that no single hospital receive more than $100,000. It also appropriates $900,000 to suicide prevention activities, including $400,000 to a suicide prevention hotline service, and appropriates $500,000 for the DHHS to contract with programs to help individuals with serious mental illness to attain and maintain supported housing.

Substance Use Disorder Crisis Response

Much of the additional funding to be used specifically for substance use disorder crisis response in the State Budget stems from the additional $12.0 million in federal State Opioid Response Grant funding received by the State and included in the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget. The State appropriated $1 million for SFY 2020 specifically to upgrade existing and create new substance use disorder treatment and recovery housing facilities. The State Budget allocates $450,000, which does not lapse, to the DHHS to help provide emergency shelter and stabilization services to those experiencing urgent substance use disorder-related symptoms in high-need areas of the state by the end of March 2020. The State Budget also specifically appropriates $750,000 over the biennium to support existing Safe Stations in Manchester and Nashua.

Finally, the State Budget includes language that raises the legal age for consuming or possessing tobacco products to 19 years old, an increase from the prior age of 18 years old. The new statute also defines electronic cigarette and liquid nicotine products in law, and sets the minimum age for purchasing and possessing those products to 19 years old as well.

Agency-Wide Funding Reduction and Keno Revenue Stream

After making appropriations in individual line items, including substantial funding increases discussed above, the State Budget required that the DHHS reduce its total expenditures by $25 million for the biennium. These reductions, which came in the form commonly referred to as a “back-of-the-budget cut,” can come from any component of the DHHS budget except for the appropriations made for developmental services, county programs, or Medicaid reimbursement rates. The DHHS is required to produce a plan for these reductions and submit it for approval to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee before January 2020. These reductions are in addition to the lapse requirements that all State agencies, including the DHHS, are expected to meet by the Legislature.[xxvi]

The State Budget removed a provision that dedicates a specific portion of Keno revenue to the DHHS to support research, prevention, intervention, and treatment services for “problem gamblers,” as identified in statute. All Keno revenue, beyond the 8 percent allowed to be retained by the licensee, goes to the Education Trust Fund following this change.

Housing Services and Policies

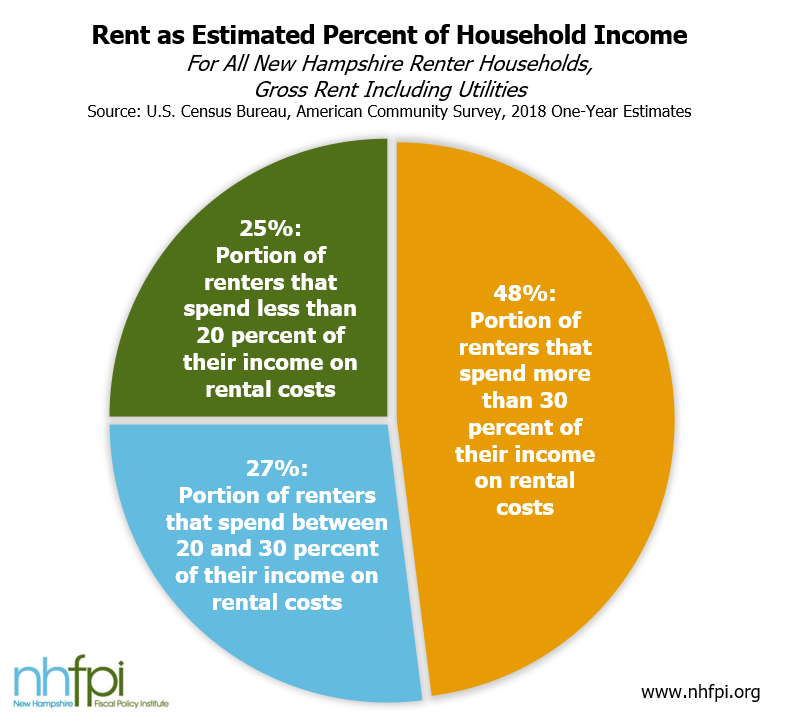

Affordable housing can be very difficult to find in New Hampshire. Nearly half of all renter households are paying more than 30 percent of their incomes in rent and utilities. Median home prices have been rising notably faster than inflation, and the number of overall homes listed has dropped 41 percent in the last five years, according to the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority.[xxvii]

Housing shortages typically result in higher housing prices, which may disproportionately limit housing opportunities for people with limited resources and low incomes as well as restrict the state’s ability to attract workers and residents from other places. The State Budget made ongoing investments that, while they may be dwarfed by the scale of the shortage of affordable housing, help alleviate the problem.

The State Budget establishes a dedicated funding source for the Affordable Housing Fund. The Fund, which is administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority, provides grants and low-interest loans for building or acquiring housing affordable to people with low-to-moderate incomes.[xxviii] The State Budget appropriates $5 million from General Fund surplus dollars in SFY 2020, and then dedicates $5 million every year from Real Estate Transfer Tax revenues to the Affordable Housing Fund beginning in SFY 2021.

Also included in the State Budget are additional appropriations for housing services during the budget biennium, including:

- $2 million for eviction prevention assistance through the provision of short- and medium-term rental assistance

- $1 million in rapid re-housing programs to prevent homelessness, improve affordable housing, and increase transitional housing by collaborating with local organizations

- $1 million for homeless shelter case management to connect clients to other supports, such as medical and mental health care and social service programs

- $400,000 for outreach efforts to homeless youth to support transitions to shelter and housing

Additionally, the State Budget establishes a state-level Housing Appeals Board. The Board is designed to be an optional, parallel track to the Superior Court system for local disputes over housing projects. The Board will be comprised of three members, at least one of which must be a licensed attorney and one of which must be a land surveyor or professional engineer. Board members shall be full-time employees, appointed by the New Hampshire Supreme Court and commissioned by the Governor, and have staggered five-year terms. The Board will hear land disputes and has the authority to affirm, modify, or reverse decisions of municipal boards, committees, or commissions related to housing and housing development. Decisions from the Board can be appealed to the New Hampshire Supreme Court. The Housing Appeals Board is funded with a $415,000 appropriation that first takes effect in SFY 2021.

Transportation

The State Budget makes some key investments in transportation, and shifts appropriations and modified revenue sources to support highway-related operations. Although the State Budget funds critical components of transportation efforts in the state, bonded investments and other major projects may be incorporated in the Ten Year Transportation Improvement Plan or the Capital Budget, both of which are passed separately.[xxix]

The State Budget appropriates approximately $14.7 million for the Department of Transportation’s vehicle fleet equipment replacement program. It appropriates $1.87 million to demolish and remove structures on State-owned property, and more than $1.4 million for Intelligent Transportation Systems, such as traffic cameras and messaging billboards, and bridge painting projects. The State Budget provides an additional nearly $9.7 million in support for certain public transit operations relative to the amount appropriated in the prior budget, primarily due to an increase in federal grants.

To support funding transportation projects, the State Budget shifts nearly $4.0 million from the General Fund to the Highway Fund. It also provides additional support to the Highway Fund by diverting plea-by-mail revenue for those pleading guilty of certain motor vehicle violations from being treated as agency revenue for the Department of Safety to the Highway Fund; this change is expected to generate $8.4 million for the Highway Fund each year of the budget biennium. The State Budget also establishes a $10 increase in license fees for each federal Real ID-compliant license issuance or renewal.

The State Budget alters certain other transportation policies that may impact funding. The State Budget explicitly permits the use of federal dollars to develop project plans to expand passenger rail in the Nashua-Manchester-Concord corridor, and permits the use of tolling credits to support the project. It also permits the sale of multiple properties purchased with State or federal highway funds, or turnpike funds, at one time. Finally, the State Budget repeals the Maine-New Hampshire Interstate Bridge Authority, including removing a New Hampshire statutory prohibition on the Authority’s ability to toll the three bridges connecting Portsmouth to Kittery, Maine without legislative approval.

Justice and Public Protection

The State Budget changes several appropriations and policies relative to the State’s administration of justice operations and public protection. The State Budget establishes new State Trooper positions, as well as a new detective position in the Cold Case Unit, in the Department of Safety. The State Budget also funds a new Cold Case attorney in Department of Justice. The Department of Corrections receives funding for two new Adult Parole Board positions, and is granted more flexibility to move funds across personnel compensation budget lines.

Funding for forensic laboratory caseloads and narcotics enforcement and investigations was increased by $587,700, while $1.45 million more was appropriated for State Trooper salaries.

The State Budget also alters the State Commission for Human Rights by attaching it administratively to the Department of Justice.

State Administrative Services Changes

The State Budget provides the Department of Administrative Services (DAS) with the authority, following the approval of the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Governor and Executive Council, to make transfers of funds for operational purposes to the DAS from any other agency to effectuate consolidation or deconsolidation of human resources, payroll, and business processing functions within State government. The DAS may also, with approval from the Governor and the Executive Council, eliminate unnecessary positions or transfer any positions within or between the DAS or any other agency “if the commissioner of administrative services concludes that such transfers or eliminations are necessary to effectuate the efficient consolidation or deconsolidation of human resources, payroll, or business processing functions within state government.” Additionally, the DAS may establish a total number of personnel required for human resources, payroll, and business processing functions within the Executive Branch of State government.

The DAS is also given the authority by the State Budget to not comply with the requirements under a 2016 Executive Order related to the identification and implementation of energy efficiency projects and the monitoring of energy and water use, use of fossil fuels, and greenhouse gas emissions during the biennium. Other State agencies are required to annually pay the DAS 75 cents per square foot of space they occupy in DAS-maintained and serviced buildings, and the DAS does not have to comply with certain Legislative Budget Assistant audit recommendations.

Additionally, the DAS must conduct a comprehensive review of the State’s personnel system, with an appropriation of $150,000 for this purpose. The DAS also received $1.3 million for scheduling software.

Economic Development and Other Policies

The State Budget includes a collection of policies targeted specifically at economic development and supporting certain business sectors, as well as other policies that are likely to have an impact on Granite Staters and State government operations.

Included in the State Budget is language establishing the Office of Outdoor Recreation Industry Development. Located within the Department of Business and Economic Affairs, this Office will coordinate promotion of outdoor recreation between federal, state, and local governments; work with stakeholders to promote economic development and attract more people to the state; promote relevant training and curricula for members of the outdoor industry and the manufacturing workforce with stakeholders and academic institutions; and recommend policies to enhance recreation.

The Department of Business and Economic Affairs was appropriated $250,000 over the biennium to support the Small Business Development Center and its programs. However, the State Budget suspends the contribution of 3.15 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax receipts to the State’s travel and tourism development agency.

The State Budget also appropriates $1 million to the Community Development Finance Authority for the Community Development Fund, which is newly-established by the State Budget to provide flexible loan capital for community development initiatives, one-time capital infrastructure revitalizations, and strategic investments.

Relative to health care and economic development, the State Budget creates the legal framework for Association Health Plans. These arrangements, newly permitted by the federal government, would allow entities meeting certain requirements, such as trade associations or groups of employers associated by industry or geography, to make health coverage available to their employees and their beneficiaries.

Other Policy Changes

Other changes and appropriations in the State Budget addressed a wide variety of policy areas, including:

- a $6 million appropriation to cover the costs of collective bargaining agreements to be reached with State employees

- alterations to the law guiding use of funding by the Public Utilities Commission to implement an energy efficiency resource standard, and requiring that no less than 20 percent of the portion of funds used for low-income energy efficiency programs

- permission for State agencies to generally provide documents by electronic mail instead of mail upon request

- the removal of specific geographic references for services to be provided with the State funding appropriated to New Hampshire Legal Assistance

- suspension of the State Demographer position for the State Budget biennium

- requiring the Governor to submit the State Budget’s Trailer Bill by February 15 of each odd-numbered year, to match the requirements for the submission of the State operating budget[xxx]

Non-Education Aid to Local Governments

In addition to local education aid, the State Budget appropriates aid to local governments, including direct aid to municipalities, to support both specific areas of investment and general revenues, some of which is described as property tax relief. Local governments have generally received less aid from the State than they did prior to the economic recession of 2007-2009 in recent years. Prior to this State Budget, local governments had received additional aid in the form of a one-time distribution of transportation aid, funds for school infrastructure, and increased aid to local governments for full-day kindergarten students.[xxxi]

The new State Budget makes additional one-time appropriations to local governments outside of the sphere of local public education. The most significant of these changes is the appropriation of $40 million in one-time aid to municipalities, which will be delivered in two, $20 million installments in each fiscal year of the State Budget. The aid will be appropriated based on two factors, both of which are related to the number of school children who are residents of a municipality. Twenty percent of the aid will be distributed based on the percentage of students statewide that are residents of a municipality. The remaining 80 percent of the aid will be distributed based on the percentage of the state’s total number of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals that live in the municipality. This aid is unrestricted and can be used by the municipality for any purpose, and is a deviation from the previous revenue-sharing formula. The prior formula for sharing revenue with municipalities is still suspended in the new State Budget, and this $40 million in aid is a one-time appropriation for this State Budget biennium.

Municipal governments also received additional limited environmental grants for eligible wastewater projects. This aid, totaling approximately $7.4 million in additional dollars, extends to infrastructure projects that have achieved substantial completion by December 31, 2019, dependent on funding availability.

Relative to funding and support for municipal operations, the State Budget:

- provides $2.4 million to local and county law enforcement agencies for substance misuse enforcement program activities

- provides $500,000 in grants for local firefighters to have medical examinations for heart and lung disease

- establishes a fund at the Department of Agriculture, Markets, and Food that would assist municipalities with the cost of caring for animals pending the resolution of any legal action related to animal cruelty

The State Budget also continues the suspension of a formula designed to share more Meals and Rentals Tax revenues with municipalities over time, which keeps the Meals and Rentals Tax aid to municipalities at the same level as during the prior biennium. The Meals and Rentals Tax statute requires 40 percent of revenue to be sent to municipalities on a per capita basis, but subsequent statutes have intervened and resulted in about 21 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax revenue going to municipalities in SFY 2018.[xxxii]

Tax and Revenue Policy Changes

The State Budget makes significant revenue policy changes, particularly relative to the State’s two primary business taxes. These two taxes, the Business Profits Tax (BPT) and the Business Enterprise Tax (BET), are the largest and fourth-largest tax revenue sources for the State. The State Budget’s statutory language includes potential future changes to business tax rates, dependent on revenue, and changes to the tax bases, or the pool of economic activity that is taxable under these revenue sources. There are several other key revenue policy changes as well, two of which expand tax bases for other taxes in New Hampshire.

Business Tax Rates

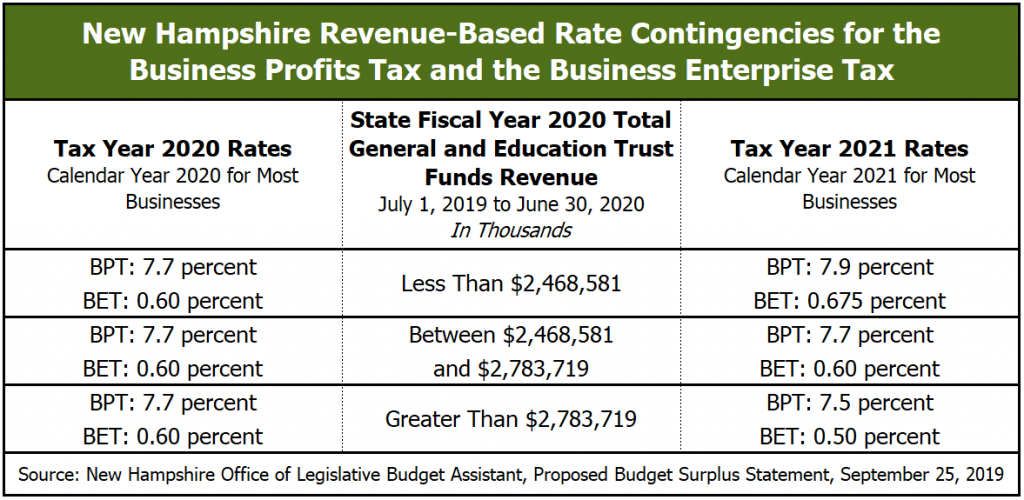

The State Budget alters the law governing future business tax rates in New Hampshire. Under previous law, New Hampshire’s BPT rate was scheduled to drop to 7.7 percent for tax year 2019, and to 7.5 percent for tax year 2021. The BET rate was scheduled to drop to 0.6 percent for 2019 and 0.5 percent for 2021.[xxxiii] Under the new State Budget, these tax rates are set at 7.7 percent for the BPT and 0.6 percent for the BET for 2019 and every year thereafter. However, those rates may change starting in 2021 depending on the State’s revenue collections.

The State Budget includes a trigger mechanism that will change the rates of the BPT and the BET, starting in tax year 2021, if the total revenues for SFY 2020 deviate from the State’s revenue plan for the General and Education Trust Funds combined by more than six percent. If revenues are more than six percent higher than the State’s revenue plan for the year, which is established by revenue projections in the State Budget, then the tax rates will drop to 7.5 percent of the BPT and 0.5 percent for the BET in 2021. However, if General and Education Trust Funds revenues are more than six percent lower than the State revenue plan, the business tax rates will go up to 7.9 percent and 0.675 percent, which are equivalent to the rates from 2018. The range in which the tax rates will stay the same, between six percent below estimates and six percent above estimates, is just over $315.3 million.

Through the end of November 2019 (SFY 2020), total revenues for the General and Education Trust Funds were 1.3 percent above the State revenue plan.[xxxiv] The largest sources of variable revenue for the General and Education Trust Funds include the BPT and BET, the Meals and Rentals Tax, the Tobacco Tax, the Real Estate Transfer Tax, the transfers from the Liquor and Lottery Commissions, the Insurance Premium Tax, and the Interest and Dividends Tax.[xxxv]

Holding the rates at 7.7 percent for the BPT and 0.6 percent for the BET, which is the scenario under the State Budget’s revenue projections, would increase revenues by an estimated $12.3 million relative previous law, which would have continued to set business tax rates lower.

Business Tax Base Changes

Although any rate increases are likely to increase State revenues, the new State Budget also enacts some provisions that broaden the tax base overall. These provisions are all projected to increase revenue.

First, New Hampshire’s BPT is based in part on the federal corporate tax code, using it as a reference for calculating the business tax base. New Hampshire’s reference does not automatically update with changes to the federal tax code, however, and instead references a fixed point in time. As a result, New Hampshire’s BPT base had not changed to reflect the federal corporate tax overall that passed as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which was signed into law in December 2017. The new State Budget updates the BPT tax base to conform with most aspects of the federal corporate tax code that changed relative to New Hampshire’s reference. The BPT base remains decoupled from the Internal Revenue Code 179 deduction for business capital purchase expenses, as well as bonus depreciation deductions and deductions for certain domestic production activities.[xxxvi] The BPT base was altered in the State Budget separately to conform with the portion of the federal tax code that covers Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income, which is a form of global minimum tax that is designed to cover income from assets such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights held in other countries to discourage profit-shifting within large firms with multiple components.[xxxvii] State Budget policymakers projected that conforming with the federal tax overhaul in this manner will increase revenues for the General and Education Trust Funds by $57.5 million during the biennium.

Second, the State Budget makes changes to the formula for calculating the amount of sales an interstate business must attribute to New Hampshire, and thus its New Hampshire tax liability, by moving to market-based sourcing. Business tax liability in New Hampshire for a business that operates in many different states is calculated through a process called apportionment. Apportionment for business taxes is determined based on a combination of the fraction of a business’s property, payroll, and sales that are in New Hampshire. Sales of services are determined by where the majority of the cost of performance of that sale is incurred. The new State Budget shifts the State’s apportionment formula to market-based sourcing for the accounting of service sales, which includes the fraction of the market that New Hampshire service sales compose of a business’s sales, rather than where the cost of service performance is most incurred.[xxxviii] This change applies to both the BPT and the BET in 2021, and was projected to increase revenue to the General and Education Trust Funds by $10 million in SFY 2021.

Third, the State Budget includes changes to the business tax apportionment formula to move from considering property, payroll, and sales locations to only considering sales in apportionment. This shift to “single-sales factor” would not take effect until 2022, and would only occur if authorized by a committee established in the State Budget to study the issue. As this change would occur after the biennium ends, there is no projected revenue impact. Single-sales factor may be disproportionately helpful for entities that export products from New Hampshire for sale in other states, such as manufacturers, but may also add volatility to business tax revenue if property and payroll, which may be more stable than sales, are removed from the calculation.

Fourth, the State Budget extends the Coos County Job Creation Tax Credit through 2027. The Tax Credit would have expired in tax year 2022. Although this tax credit very likely reduces revenue relative to the amount that would have been collected without its existence, the change has no revenue impact during the State Budget biennium, and the total amount of tax credit used during SFY 2018 was $114,000.[xxxix]

Other Revenue and Tax Policy Changes

Although the business taxes underwent key reforms in the State Budget, they were not the only revenue sources that were altered. The tax bases for two other tax revenue sources were also expanded.

The Tobacco Tax base was altered to include electronic cigarettes. The tax levied on electronic cigarettes, which are defined in the new statute, include a tax of $0.30 per milliliter on the volume of liquids or other substances in a closed cartridge or other container of liquid containing nicotine, or an 8 percent tax on the wholesale price of closed cartridges or a container not intended to be opened. These changes to the Tobacco Tax base were expected to increase revenue by $5.7 million in SFY 2021.

The second tax with an expanded tax base under the new State Budget the Communications Services Tax. This tax base was expanded to include pre-paid phone card service plans and Voice over Internet Protocol services. State Budget policymakers projected General Fund revenues would increase $4.0 million during the biennium as a result of this change.

Other revenue policy changes enacted in the State Budget include adding auditors to the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, which was anticipated to yield $2.2 million in additional revenue during the State Budget biennium, and reducing employer contribution rates for the Unemployment Trust Fund.

The State Budget also removed the requirement that the Liquor Commission reduce its own budget if revenue targets for transfer from the Liquor Commission to the General Fund identified in the State revenue plan are not achieved.

Fund Balances

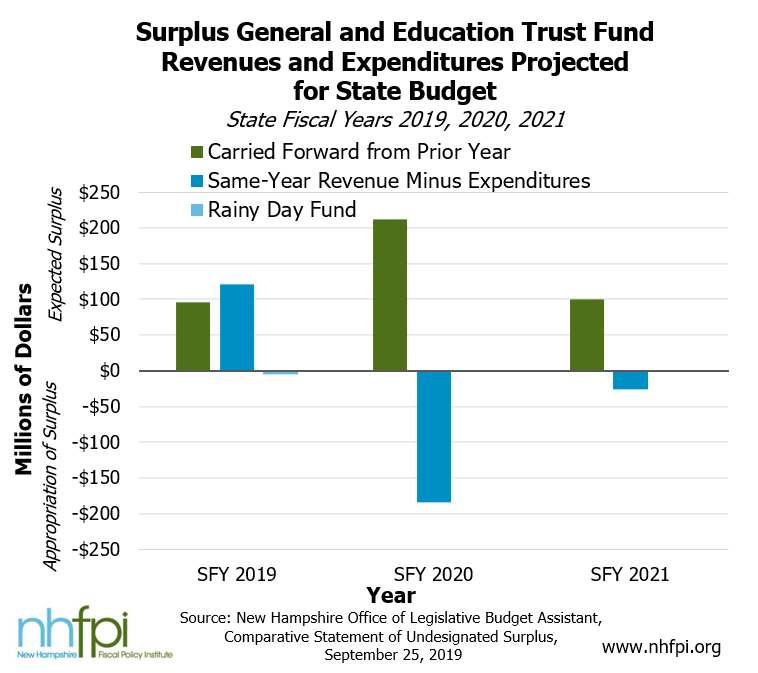

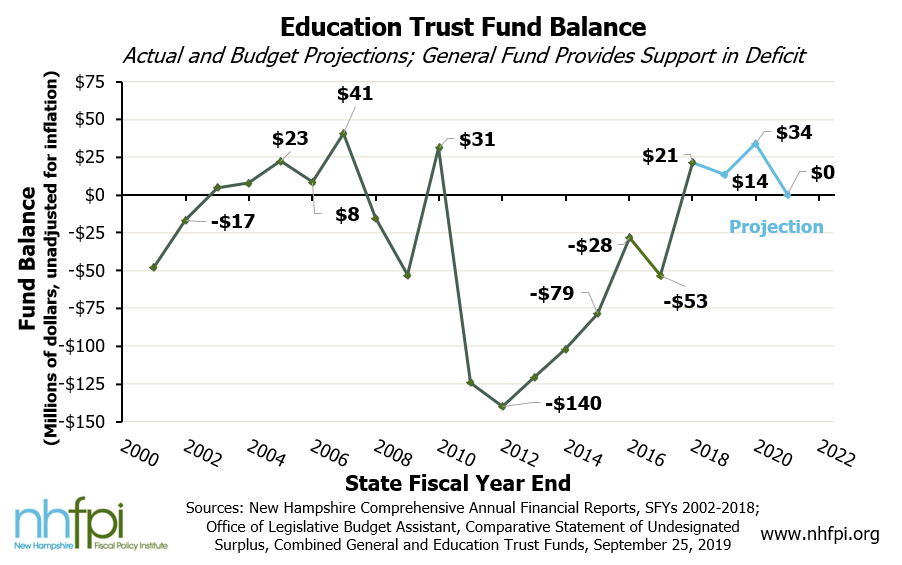

The State Budget employs surplus dollars during the biennium to fund expenditures sourced from the General and Education Trust Funds, including one-time appropriations in education and municipal aid. The State Budget carries a significant surplus, approximately $211.5 million, from SFY 2019 forward into SFY 2020 and the budget biennium. State Budget writers had the benefit of a larger than previously-anticipated lapse, and used the surplus to appropriate $62.5 million from SFY 2019’s Education Trust Fund to an account established specifically to fund one-time Adequate Education Aid in SFY 2021. The Education Trust Fund was also bolstered by a one-time appropriation from the General Fund of $68.1 million in SFY 2020. The Education Trust Fund has historically frequently operated with a deficit and typically draws on the General Fund to achieve balance. However, this State Budget, in part due to the planned transfer from the General Fund, projects year-end balances for both SFY 2020 and SFY 2021, although the balance at the end of the budget is projected to be only $64,000.[xl]

The State Budget also shifted some disbursements previously funded by the General Fund to draw support from the Education Trust Fund. School Building Aid, support for tuition and transportation, and Special Education Aid beyond the assistance included in the Adequate Education Aid formula, was previously funded through the General Fund, but are supported by the Education Trust Fund for this budget biennium.

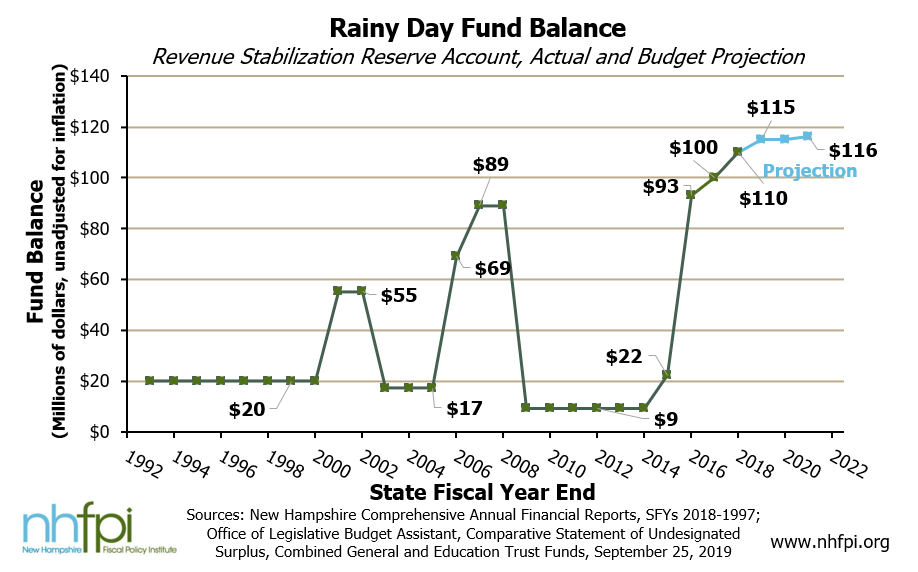

The Rainy Day Fund, formally titled the Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account and technically a portion of the General Fund, also receives a boost in this State Budget. The State Budget transfers $5 million of the more than $216.5 million projected positive balance at the end of SFY 2019 to the Rainy Day Fund, and anticipates transferring approximately $1.2 million additional dollars at the end of the biennium to the Rainy Day Fund from the projected budget-end surplus.

Concluding Discussions

A budget is a statement of values and priorities. New Hampshire’s State Budget provides increased investments in education, health services, aid to local governments, and housing, reflecting some of the top fiscal and economic challenges facing the state. However, some of these investments are designed to be one-time, raising questions about whether these investments can substantively address the problems they are designed to help alleviate.

Faced with crises relative to substance misuse and mental health, policymakers expanded the availability of health services in New Hampshire significantly. Extending mobile crisis units to statewide coverage, and including services for children, provides a critical first response that can be less expensive and meet mental health needs in a more appropriate manner than some alternatives, such as hospital emergency rooms. Adding more physical infrastructure, such as beds and spaces for mental health patients at New Hampshire Hospital and in the community, will help Granite Staters in crisis get the care and assistance they need in appropriate settings. The State Budget aims to eliminate the waitlist for services for those with developmental disabilities through substantial new investments, and makes policy changes that will ease the financial administration of those programs. Finally, increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates provides more systemic support for the health care workforce and helps providers deliver Medicaid services to Granite Staters with low incomes. Some of these investments, particularly the reimbursement rate increases, will likely require additional resources in the future to effectively alleviate health care workforce shortages and gaps in services.

The State Budget layers significant additional aid for local public education, much of which is targeted aid for students from poor families and municipalities with relatively less ability to raise funds locally, on top of the existing education funding formula. Increases in investment for public education stretch across the age spectrum, from added funding for full-day kindergarten students to more support for the University System and programming targeted at older students at the State’s community colleges.

The targeting of aid to communities with lower amounts of property wealth per student also demonstrated a recognition of disparities in local fiscal capacities. Additional aid to municipalities for general purposes, distributed in large part based on the number of children from households with low incomes that are residents of those cities and towns, also may help reduce upward pressure on property taxes in some of the communities that can least afford to increase them. These appropriations by State policymakers indicate an acknowledgement of the State’s recent underinvestment in both public education and property tax relief.

However, many of these appropriations only appear in a one-time fashion. The new local public education aid targeted at communities with more poor students and towns with low property values will only be delivered for one year. The municipal aid is designed to be a one-time grant distributed over two years. Appropriations for specific, health-related programs at the University System are provided as a single infusion. The end date for grants to local wastewater projects completed within a certain timeline was extended, but local governments still face an end date for that assistance. The increase in funding for the school building aid program was projected to fund an additional three projects, after being largely suspended for ten years.

Policymakers showed a willingness to increase revenues to fund these priorities, including the potential elimination of a planned future decline in business tax rates. The reforms to the business tax base should include additional profits from large businesses operating across interstate and international borders in the New Hampshire tax base, but does not resolve some of the concerns with international business profit shifting. Other tax base changes are likely to generate more revenue as well. However, policymakers may have to find additional State revenue in the future to effectively address constraints that confront Granite Staters in this economy.

The State Budget takes some critical steps toward addressing the challenges facing New Hampshire and establishes key forward-looking policy processes around planning for future education funding and responding to health needs of residents. These investments will address some of the most significant instances of the challenges surrounding education funding, health services, housing, and property taxes. Many of the steps this budget takes, however, are either incremental, temporary, or both relative to the magnitude and persistence of the problems. More investments will be required in the future to deliver services efficiently, effectively, and sustainably for individuals, children, and families in the Granite State.

Revision, December 26, 2019: A correction and clarification regarding the description of the changes made to the Job Training Program and Senate Bill 2 revised the original text to identify the correct year for the bill’s alternate title and indicate that Senate Bill 2 did not become law.

Correction, February 18, 2020: A correction was made to the figure representing the appropriation for Medicaid reimbursement rate increases.

Endnotes

[i] Source materials related to the State Budget are available on the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s web page for the SFYs 2020-2021 budget process. These source materials are used throughout this Issue Brief. For more information on the State Budget and previous iterations and proposals, see NHFPI’s NH State Budget web page.

[ii] For more information about the different components of the State Budget and understanding the magnitude and components of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s September 2017 Issue Brief Measuring the Size of New Hampshire’s State Budget.

[iii] For more discussion of the New Hampshire economy and the challenges stemming from workforce constraints, see NHFPI’s August 2019 Issue Brief New Hampshire’s Workforce, Wages, and Economic Opportunity and NHFPI’s June 2018 Issue Brief New Hampshire’s Economy: Strengths and Constraints. See also NHFPI’s Common Cents November 20, 2019 post New Hampshire Trails in Higher Education Funding and associated sources.

[iv] For a breakdown of aggregate school district revenues and expenditures in New Hampshire, see the New Hampshire Department of Education, State Summary Revenue and Expenditures of School Districts 2017-2018, December 17, 2018. For more information on the Statewide Education Property Tax, see NHFPI’s May 2017 Revenue in Review resource.

[v] To see a graph showing an example of the disparities between municipal property tax bases per school pupil in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s February 22, 2019 presentation Funding the State Budget and Other Public Services.

[vi] For an explanation of Adequate Education Aid policy, see NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[vii] For more information, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Schedule of State Aid to Cities, Towns and School Districts, January 1, 2009, and the updated version from October 12, 2018.

[viii] For an explanation of the Adequate Education Aid formula immediately prior to the creation of stabilization grants, see the New Hampshire Department of Education, FY 2010 How State Aid Was Determined. See also Chapter 258, Laws of 2011, the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant January 2019 Fiscal Issue Brief Calculating Education Grants: Stabilization Grants, and NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[ix] To understand the inflation adjustment and the methodology prescribed in law, see RSA 198:40-d.

[x] For more on education funding, kindergarten funding, and Keno revenue, see NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget, NHFPI’s November 8, 2017 Common Cents post Elections Highlight Continuing Questions About Keno Revenue, and the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant July 2017 Fiscal Issue Brief Senate Bill 191 (2017).

[xi] For more information on the free and reduced-price school meal program, see the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Child Nutrition Programs: Income Eligibility Guidelines (July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020), published March 20, 2019. For the official federal poverty guidelines, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs, published February 1, 2019.

[xii] NHFPI calculations based on data presented by New Hampshire Department of Education, Estimated FY2021, Municipal Summary of Adequacy Aid, November 15, 2019.

[xiii] NHFPI calculations based on data presented by New Hampshire Department of Education, Estimated FY2021, Municipal Summary of Adequacy Aid, November 15, 2019 and the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Comparison of Education Funding, Current Law Vs. Budget Compromise FY 2021, September 25, 2019.

[xiv] The Governor’s budget proposed continuing the suspension of the traditional school building aid program, but also proposed a $63.7 million one-time appropriation of school building aid to be allocated through a separate program, which would have been established for the purpose of distributing those one-time funds. The Governor’s budget would have appropriated $32 million in SFY 2020 and $30 million in SFY 2021 to the traditional program, while the final State Budget appropriated $38.5 million and $30.5 million in SFYs 2020 and 2021, respectively. Documentation presented to the Legislature indicated the final budget’s level of funding would support the top three ranked school building projects.

[xv] The Granite Advantage Health Care Program is New Hampshire’s version of expanded Medicaid under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. For more information on the Granite Advantage program, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

[xvi] Historical TANF balance information and SFY 2019 projections provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, including in the document “TANF Information, DHHS 3/22/2019.” Projection of a final balance of $13.5 million at the end of SFY 2021 presented in the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Summary of HB 1 and 2 Committee of Conference Report, June 21, 2019.

[xvii] For more information on this program, see the DHHS State Loan Repayment Program web page.

[xviii] The estimated number of Medicaid enrollees in New Hampshire is based on the DHHS November 2019 Caseload Statistics Report.

[xix] To learn more about the impacts of Medicaid reimbursement rates, see NHFPI’s March 2019 Issue Brief Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Care Service Delivery Limited by Workforce Challenges.

[xx] To read more about the prior Granite Advantage program funding structure, see NHFPI’s April 27, 2018 Common Cents blog House Finance Committee Modifies Medicaid Expansion Work Requirements, Tweaks Funding Structure.

[xxi] Funding for additional positions at the DHHS Division of Children, Youth, and Families was authorized in Chapter 43, Laws of 2019, but the State Budget added language forbidding the appropriations from being transferred to other purposes. This change will likely prevent the positions from losing their funding and being transferred elsewhere if they are not filled.

[xxii] The language in this section of the State Budget reflects the language in the separately-enacted Chapter 44, Laws of 2019.

[xxiii] TANF fund balance information provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, including in the document “TANF Information, DHHS 3/22/2019.” The projection of a TANF balance at the end of SFY 2021 was provided by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant relative to the Committee of Conference budget in June 2019, and the September compromise budget did not appear to change any provisions related to TANF-supported appropriations.

[xxiv] For the three percent increase in county caps based on the level of funding appropriated, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Detail Change: Committee of Conference vs. House, June 24, 2019, page 15.

[xxv] For more information on county obligations related to Medicaid, see NHFPI’s August 2019 Fact Sheet County Medicaid Funding Obligations for Long-Term Care.

[xxvi] For more information on back-of-the-budget adjustments and lapses, see NHFPI’s September 2017 Issue Brief Measuring the Size of New Hampshire’s State Budget.

[xxvii] For more information on recent housing data, see NHFPI’s October 2019 Fact Sheet Census Bureau 2018 Estimates for Income, Poverty, Housing Costs, and Health Coverage, the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s November 2019 Housing Market Report, and NHFPI’s August 9, 2019 Common Cents post, Continued Rise of NH’s Rental Costs Increases Financial Burdens on Residents. For historical inflation in the northeastern United States, see the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, Northeast Region, accessed December 2019.

[xxviii] For more on the Affordable Housing Fund, see the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority Financing Programs web page.

[xxix] For additional information on appropriations included within and outside of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s February 2017 Building the Budget resource.

[xxx] For more information on the different components of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource and NHFPI’s September 2017 Issue Brief Measuring the Size of New Hampshire’s State Budget.

[xxxi] For more information, see NHFPI’s presentation titled “How We Fund Public Services in New Hampshire,” with slides 43 and 44 from November 13, 2019 showing the changes in aid to local governments through the State Budget over time. For additional information, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Schedule of State Aid to Cities, Towns and School Districts, January 1, 2009, and the updated version from October 12, 2018. For the changes made in the previous State Budget and associated bills from 2017, see NHFPI’s July 2017 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019, particularly endnotes 6 and 17 and the associated text in the Issue Brief.

[xxxii] Calculation based on the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Schedule of State Aid to Cities, Towns, and School Districts, October 12, 2018 and the State of New Hampshire Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2018, pages 146 and 148.

[xxxiii] About 90 percent of businesses have tax years that coincide with calendar years, according to the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration. For more information on business taxes in New Hampshire and recent trends in revenues, see NHFPI’s September 2019 Issue Brief Business Tax Revenue and the State Budget and NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Funding the State Budget: Recent Trends in Business Taxes and Other Revenue Sources.