It has been over a decade since the end of the last recession. During this time, investments and funding for public higher education across the nation have seen reductions overall. States reduced expenditures in the aftermath of the recession, including decreased spending to support public higher education. Recent analyses from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Pew Charitable Trusts have compared states’ investments in public higher education over time. When compared to pre-recession levels, the amount of money allocated to public higher education nationwide has decreased. Students who attend public colleges and universities in their home states face the additional cost burdens of increasing tuition and fees that may stem from these funding cuts. In New Hampshire, Granite Staters face the second highest average in-state tuition at public four-year institutions in the nation. Increased tuition at public colleges and universities, and private institutions as well, contributes to student loan debt, which is now the second largest source of debt in the nation, after home mortgages.

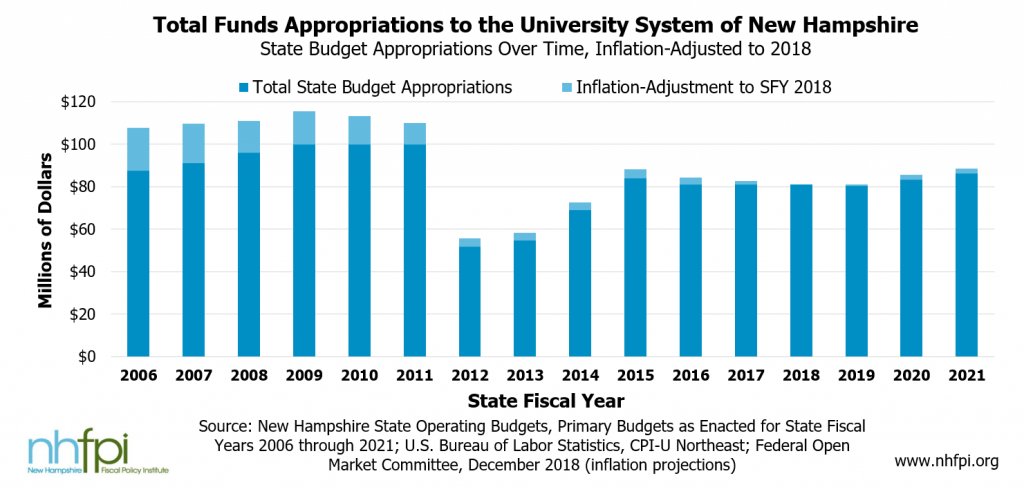

The largest reduction for public higher education funding in New Hampshire occurred during State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2012, when State Budget support for the University System of New Hampshire was reduced by nearly half of the SFY 2011 value. Since those funding reductions, all state colleges and universities across New Hampshire experienced tuition increases and changes to academic programs. The University of New Hampshire’s Durham campus, the state’s flagship public higher education institution, has an in-state undergraduate tuition and mandatory fees of about $19,000 annually for the 2019-2020 academic year.

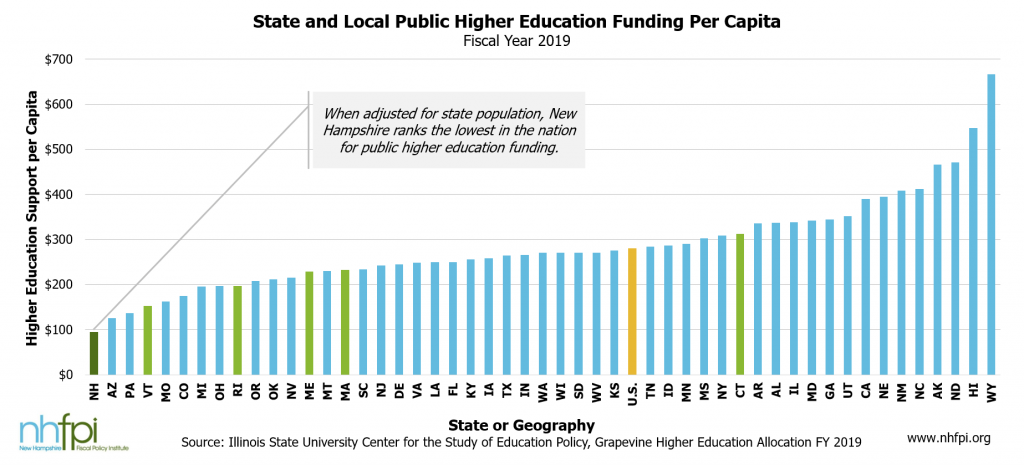

Data from Illinois State University reveals insights into how levels of funding in New Hampshire compare to other states in fiscal year 2019. Analyzing funding per capita allows for normalized comparisons between states. This normalized measure represents the amount of relative effort a state puts toward funding public higher education. New Hampshire takes the bottom rank for this measure of investment and support of public higher education, as the only state below $100 per capita in funding. The Granite State spends only $94.76 per capita on public higher education. All but nine states have funding levels above $200 per capita.

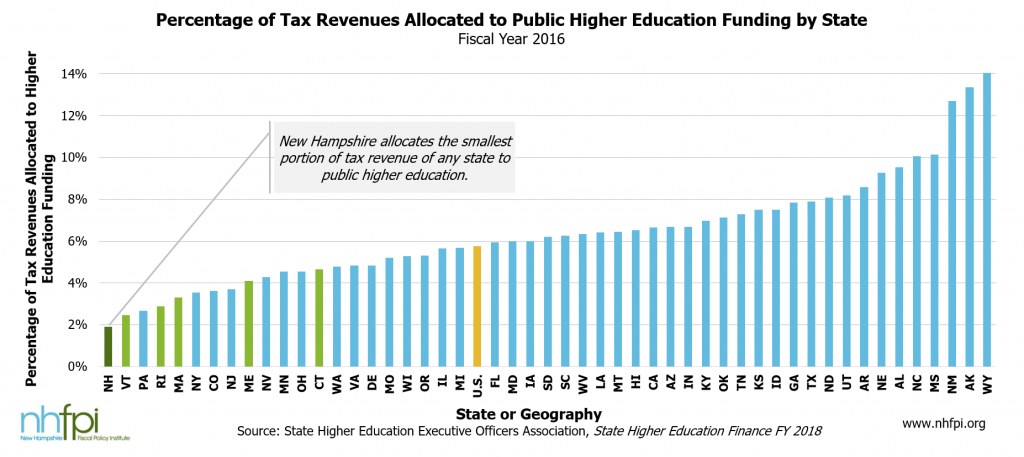

Examining higher education funding per $1,000 of personal income in the state allows for a comparison of a state’s funding given the relative income of its residents. New Hampshire again falls at the bottom of this ranking, providing only $1.56 per $1,000 of income in fiscal year 2019. The next lowest states were Pennsylvania with $2.50, and Vermont with $2.86 per $1,000 of personal income. In another key metric, New Hampshire again is awarded the bottom rank when considering the portion of tax revenue allocated to public higher education funding. New Hampshire was the only state to allocate less than 2 percent of tax revenues to public higher education. The next lowest states were Vermont at 2.5 percent and Pennsylvania at 2.7 percent of tax revenues allocated to public higher education funding. All but eight states allocate at least 4 percent or more of tax revenues to public higher education, with some states allocating over 10 percent.

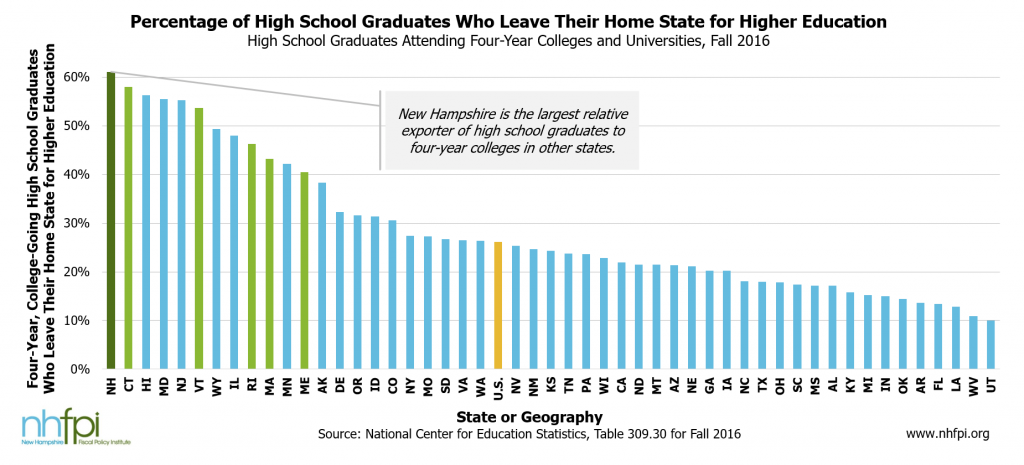

The consequences of New Hampshire’s low levels of investment in public higher education come in short- and long-term forms. More of the costs of public higher education have been shifted to students in the Granite State, which may lead to high school graduates seeking cost-competitive higher education opportunities in other states. Higher costs of attendance disproportionality discourage students from families with lower incomes from pursuing higher education. Additionally, the most recent data on the migration patterns of high school students seeking a four-year degree suggests New Hampshire is losing a disproportionate share of its students to other states. New Hampshire is, and has been since 2012, the largest relative exporter of high school students in the nation; over 61 percent of the Granite State’s high school graduates, who are heading to college, leave New Hampshire to pursue a four-year degree. Of the total number of first-year students enrolled in four-year colleges and universities in the Granite State, only 38 percent were New Hampshire residents, compared to about 73 percent of students nationally who pursue a four-year degree at a school in their home state. States with smaller geographic areas may be higher exporters of degree-seeking high school graduates, as a student may not need to travel as far to attend a school in another state as in states with larger geographic areas. However, New Hampshire is the only state where over 60 percent of degree-seeking students leave, more than double the national average.

The primary long-term risk associated with students leaving the state to pursue a four-year degree elsewhere is that they may choose not to return to New Hampshire. As the average age of Granite Staters is expected to continue to climb, in-migration of younger adults and families is key for New Hampshire’s population growth and economic expansion. Estimates from New Hampshire Employment Security show that in the short term, through 2020, increases in the amount of jobs in New Hampshire requiring at least a bachelor’s degree.

Over the last decade, the changing rate of public funding for higher education in New Hampshire has placed more financial burdens onto students. This diminishes the incentive for Granite Staters to pursue a degree in their home state. However, there are modest increases in funding to the University System of New Hampshire and the Community College System of New Hampshire for SFYs 2020 and 2021. For SFY 2020, a funding increase of $4.5 million for the University System of New Hampshire, followed by an additional $3.0 million increase in SFY 2021, has allowed in-state undergraduate tuition to be frozen for 2020-2021 academic year. These increases in State appropriations are a vital step in restoring and improving funding of public higher education in New Hampshire, while investing in the future well-being of the state.

– Michael Polizzotti, Policy Analyst