KEY POINTS

- From 2013 to 2020, New Hampshire experienced drug-related mortality rates above national averages, although it saw the largest decline over the past decade in 2024.

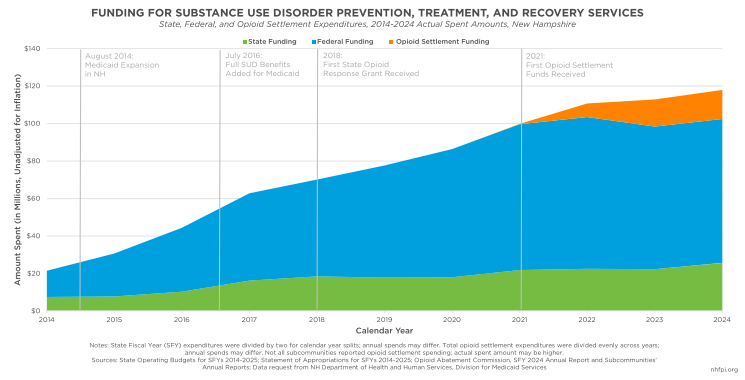

- New Hampshire has invested approximately $834.7 million in substance use disorder (SUD) prevention, treatment, and recovery since 2014.

- Around $99.3 million in opioid settlement funding has been distributed to New Hampshire since 2021, although about $14.4 million remains unspent or unobligated.

- Recent state and federal policy decisions, including work requirements and cost shares for Medicaid enrollees and funding adjustments for the Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention Fund, may hinder SUD service access and delivery.

- Despite improved services, three out of four Granite Staters did not receive needed treatment during the 2022-2023 period, suggesting ongoing challenges and barriers.

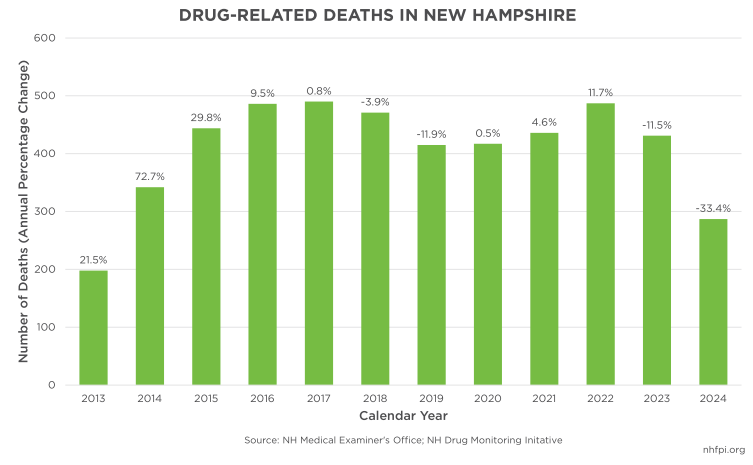

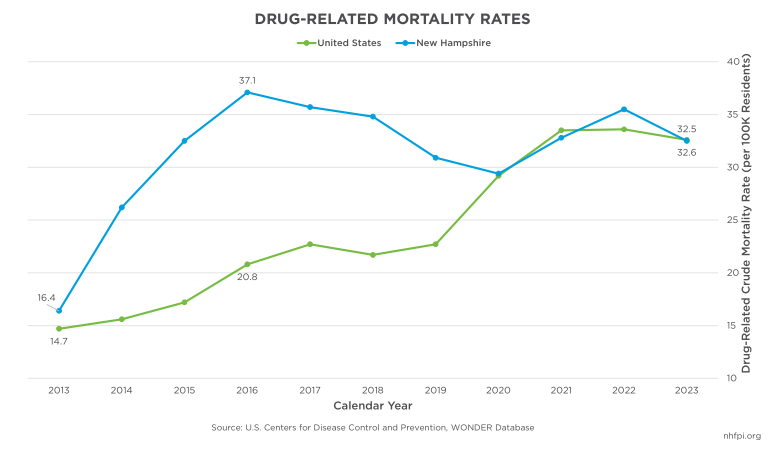

From 2013 to 2020, New Hampshire experienced drug-related mortality rates above national averages. However, in 2024, both national and statewide data showed that New Hampshire saw its largest decline in drug-related deaths in the last decade. The number of drug-related deaths in the state peaked in 2017, with 490 people dying from drug related causes. In comparison, 102 Granite Staters died from traffic-related fatalities that same year.[1] While drug-related deaths have declined to 287 reported deaths in 2024, opioids remain the primary cause of drug-related fatalities, demonstrating the continued impact of the ongoing opioid epidemic. More than three quarters, or 83.6 percent, of all drug-related deaths in the Granite State in 2024 involved opioids.[2]

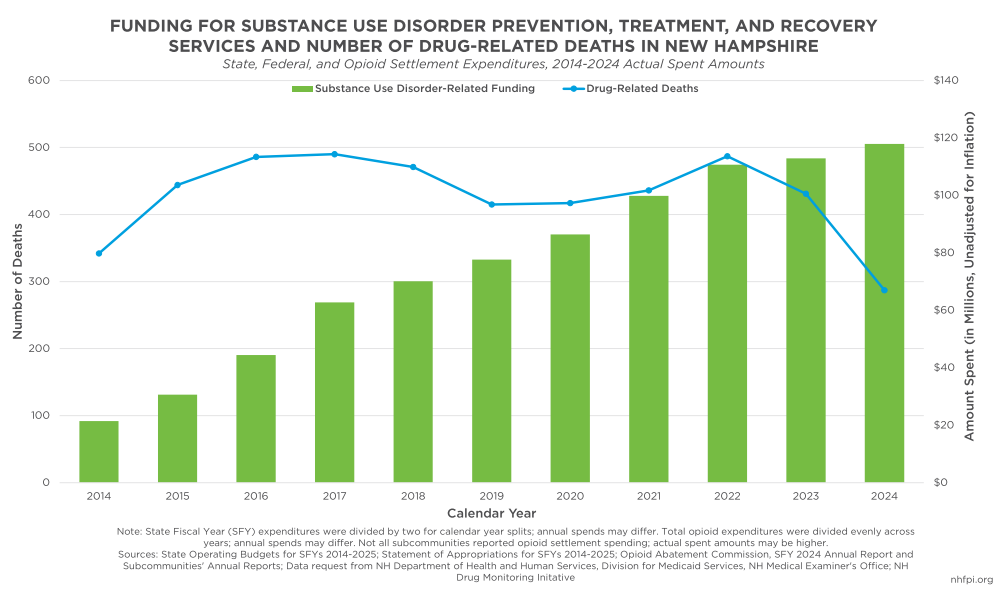

While there are many potential factors, this sharp decrease in drug-related fatalities is likely due to a continued investment in substance use disorder (SUD) prevention, treatment, and recovery services, particularly increases in prevention strategies and harm reduction services.[3] Since 2014, New Hampshire has invested more than $834.7 million in SUD services, with annual spending increasing by about 450 percent from 2014 to 2024. Increased allocations are the result of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire, as well as other critical funding sources added over the past decade, including the federal State Opioid Response (SOR) Grant and settlement funds resulting from lawsuits with opioid manufacturers. These funding streams have improved the State’s ability to expand SUD services across New Hampshire.

Nationally, SUDs continue to disproportionately impact people with low incomes, as well as those who identify as Black or Native American. These groups have historically faced higher drug-related morbidity and mortality rates due to structural barriers, such as decreased health care access, a lack of stable housing, and increased involvement with the criminal legal system. Research suggests that communities with greater income inequality also experience higher fatality rates.[4] The social determinants of health play a role in what services people are able to obtain, and can impact engagement with treatment and sustained recovery.[5]

In addition to declining deaths, several studies have found that investments in SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery could lead to more cost savings in the future. These include declines in criminal legal system spending due to reductions in crime, decreased usage of costly emergency health care services, productivity gains as more people remain in the workforce while receiving treatment, and reductions in social service demand.[6]

This Report delivers a comprehensive picture of how New Hampshire has funded substance use disorder (SUD) prevention, treatment, and recovery services, drawing on both state and federal sources. It connects these funding streams to the past decade’s trends in drug-related fatalities, underscoring the critical role sustained investment contributes to saving lives. The Report also examines how other states have deployed opioid settlement funds to strengthen their response, offering lessons for New Hampshire. Finally, it looks ahead to looming state and federal funding changes that could threaten access to care, highlighting the potential challenges for Granite Staters.

Drug-Related Fatality Trends

In 2024, approximately 287 Granite Staters died from drug-related causes, the smallest number recorded in the state since 2014. Between 2023 and 2024, the number of drug-related deaths declined by an estimated 33.4 percent, the second consecutive year of declines and the sharpest year-over-year reduction across the previous ten years.[7] Early indicators suggest that positive trends may continue. Preliminary data from June 2025 show an estimated 77 drug-related deaths during the first half of the year, a smaller number than the 122 recorded deaths during the same period in 2024.[8]

Declines in recent years contrast with the sharp increases that occurred during the previous decade. Between 2013 and 2014, drug-related deaths in New Hampshire rose by 72.7 percent, the largest year-over-year increase recorded in New Hampshire history. Drug-related fatalities continued to increase during the following two years, before leveling out and declining slightly before the COVID-19 pandemic. Beginning in 2020, New Hampshire again saw increases in drug-related deaths, with the largest of these more recent annual increases totaling 11.7 percent occurring from 2021 to 2022.[9] Substantial declines over the last couple of years may be due to enhanced funding and services, such as the introduction of opioid settlement funding and the increased distribution of naloxone in New Hampshire.

Recent trends in New Hampshire follow both national and regional patterns. From 2023 to 2024, drug-related deaths across the United States declined by 25.9 percent. All New England states also experienced decreases, with Massachusetts leading the region with a 36.4 percent reduction, followed by Connecticut (27.3 percent), Vermont (25.5 percent), Maine (22.0 percent), and Rhode Island (20.7 percent).[10]

While the number of annual deaths has fluctuated, mortality rates allow for more direct comparisons across states. These rates, usually expressed in deaths per 100,000 residents, measure the number of fatalities relative to the population size. From 2014 to 2018, New Hampshire’s drug-related mortality rate was among the top seven in the nation. In 2015, the Granite State experienced the second highest rate for that year, at 32.5 deaths per 100,000 residents, behind only West Virginia at 40.7 per 100,000.[11] Since 2020, New Hampshire’s drug-related mortality rate has aligned more closely with national averages, due in part to rising national rates. In 2024, New Hampshire’s rate fell to 20.0 deaths per 100,000 people, the lowest rate among all New England states that year and lower than the national average of 23.8 per 100,000.[12]

Particular groups continue to experience disproportionate negative health outcomes and a greater risk of mortality from substance use. In 2023, people identifying as Black or African American represented about 20.5 percent of drug-related deaths nationwide, despite only making up 13.7 percent of the country’s population during that same year.[13] People identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native have also historically experienced disproportionate mortality rates. In 2023, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdoses nationwide was highest among this group, at 65.0 per 100,000 people. In comparison, those identifying as white and non-Hispanic experienced a mortality rate at about half that, or 33.1 per 100,000 people.[14]

In New Hampshire, more than half of drug-related deaths in 2024 were among people age 30 to 49, with those age 30 to 39 representing nearly a third of deaths in each year since 2018. As the state’s population continues to age, older adults have also represented larger shares of drug-related fatalities. In 2024, around 12.9 percent of drug-related deaths were among adults age 65 or older, compared to only 5.8 percent in 2014. Drug-related deaths are also more common among men. In 2024, two thirds, or 67.2 percent, of fatalities in New Hampshire were among men, a relatively consistent proportion since at least 2014.[15]

Trends also differ by region and county within New Hampshire. In 2024, Hillsborough County, the state’s most populous county, experienced the highest drug-related fatality rate at 25.8 deaths per 100,000 Granite Staters. Cheshire (23.6 deaths per 100,000 residents), Strafford (23.3 deaths), Sullivan (22.9 deaths), and Coos (22.2 deaths) Counties also experienced relatively high rates. New Hampshire’s other four counties all experienced rates below 20.0.[16] Research suggests that rural areas may experience higher drug-related mortality rates due to decreased availability of services, likely driven by workforce shortages.[17]

Overview of Funding for Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services

The introduction of various new funding streams has increased spending on SUD services over the past decade.[18] From 2014 to 2024, New Hampshire invested more than $834.7 million towards SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery services, including approximately $609.1 million (73.0 percent of total spend) in federal expenditures and $188.1 million (22.5 percent) in State expenditures.[19] During this ten-year span, approximately $37.4 million (4.5 percent of total spend) has been spent in opioid settlement funding, although around half of funds allocated to New Hampshire have remained unspent.[20]

The largest federal funding streams include Medicaid; the Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (SUBG); and the State Opioid Response (SOR) Grant. State allocations are comprised of State contributions towards Medicaid and the Governor’s Commission on Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention.

Medicaid

Medicaid is the single-largest payer for SUD treatment both nationally and in New Hampshire.[21] Medicaid, a federal-state fiscal partnership, provides health coverage for adults and children with low incomes, people with disabilities, older adults, pregnant women, and certain other eligible populations. Through the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and subsequent adoption of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire in 2014, the State established the Granite Advantage Health Care Program, formerly known as the New Hampshire Health Protection Program (NHHPP) and commonly referred to as Medicaid Expansion. This program makes adults ages 19 to 64 with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $21,957 for a household of one in 2025, eligible for Medicaid coverage.[22] As of July 2025, Granite Advantage adults represented about one-third, or 31.6 percent, of the state’s total Medicaid population.[23] The federal government pays 90 percent of costs for Medicaid Expansion, a larger share than the half of service expenditures paid for most other Medicaid services in New Hampshire. This means that for every $1 that is spent on services funded through Medicaid Expansion, the State only pays 10 cents and the federal government supplies the rest of the resources.

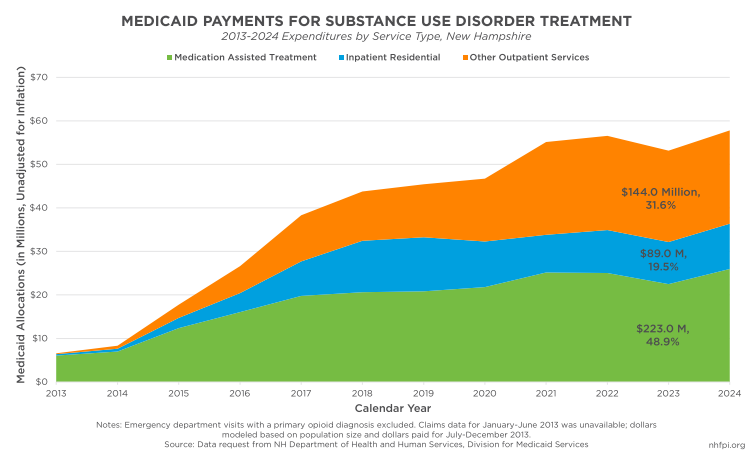

Among the $57.8 million in Medicaid funding spent on SUD services in 2024, $45.7 million (79.1 percent) were Expansion dollars, with only $4.6 million paid by the State. This structure has allowed New Hampshire to increase its service capacity without placing a significant burden on State funding. In 2024, Medicaid accounted for $57.8 million (about 49.7 percent) of the State’s total SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery spending, up from $8.3 million (38.8 percent) in 2014.[24] This substantial growth highlights Medicaid’s role in financing SUD services for Granite Staters with the lowest incomes.

In addition to improving SUD treatment access, Medicaid Expansion has decreased uncompensated care among providers by expanding health coverage for more Granite Staters. Among states that expanded Medicaid, research shows a decline in the number of uninsured opioid-related hospital visits, from approximately 13.4 percent in 2013 to 2.9 percent in 2015.[25] In New Hampshire, the state’s uninsured rate declined by more than half, or approximately 6.2 percentage points, between 2013 and 2024, likely contributing to decreased uncompensated care.[26]

Coverage requirements also play a vital role in shaping access to services. Under federal law, states are required to cover certain SUD treatments for their Medicaid recipients, with covered services typically limited to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of opioid- and alcohol-use disorders, inpatient and outpatient hospital services, and certain behavioral therapies. However, states have the option of utilizing federal Medicaid 1115 waivers to cover a broader continuum of services for SUD treatment, comprised of the nine levels of care, established by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). Services in this model include residential services, intensive outpatient programs, peer recovery support, case management, withdrawal and detox support, and other comprehensive services designed to better support individualized needs and treatment plans. As part of the passage of Medicaid Expansion in 2014, New Hampshire adopted this broader continuum coverage for Granite Advantage adults and later extended it for the entire Medicaid population in 2016.[27]

Even with these expansions, few states have extended coverage for the full continuum of services. According to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC)’s most recent comprehensive analysis, only twelve states’ Medicaid plans covered all nine ASAM levels of care in 2018. At the time of publication, New Hampshire covered seven of the nine levels under their Medicaid program, leaving out a subset of level 3, defined as intensive and population-specific services for people with cognitive challenges, developmental disabilities, or aging-related conditions; and level 4, including 24-hour nursing care and daily physician monitoring.[28]

Trends across the previous decade highlight the variety of treatment options available for Medicaid recipients in the Granite State. From 2013 to 2024, medication-assisted treatment comprised the largest share of SUD-specific Medicaid dollars in New Hampshire, with around $223.0 million spent on such treatment over the eleven-year period. Inpatient residential treatment accounted for around 19.5 percent, or $89.0 million, while about one third of the total SUD Medicaid spend, or $144.0 million, funded outpatient services, such as partial hospitalization, day programs, and other behavioral health therapy.

New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) caseload data demonstrates a similar pattern of growth. In 2024, 10,132 Medicaid recipients received SUD treatment in New Hampshire, more than four times greater than the 2,265 Granite Staters who received SUD services in 2013. Last year, enrollees receiving SUD services represented 5.4 percent of the state’s full Medicaid population. Medicaid Expansion enrollees have consistently represented more than two-thirds of SUD caseloads since 2019. In 2024, 7,012 adults with Granite Advantage coverage, or 11.3 percent of the state’s full Medicaid Expansion population, received SUD services, highlighting the program’s continued importance for treatment access.[29]

Using the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) SUD Data Book, compiled by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), allows for more direct comparisons between states. According to these metrics, in 2021, 12.9 percent of New Hampshire’s Medicaid population received SUD treatment, a higher percentage than the national average of 7.9 percent, and behind only Maine (13.3 percent) and Vermont (13.1 percent) in the New England region. Among states that had implemented Medicaid Expansion by January 2021, an average of 9.8 percent of their Medicaid populations received SUD treatment, compared to only 7.6 percent among non-Expansion states.[30] In 2021, 7.5 percent of New Hampshire’s Medicaid population was treated for an opioid use disorder (OUD), the highest percentage in the country tied only with West Virginia.[31]

Federal Funding

Federal funding to combat substance misuse comes to New Hampshire from a variety of sources. Each source has a different set of rules for, and restrictions on, its use. Collectively, federal funding is the most significant source of dollars for addressing SUD, generating about 65.1 percent of all funding used in 2024 and about 73.0 percent of funding during the 2014 to 2024 period.

Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant

The Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (SUBG) began in 1993 as part of the larger federal Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA) Reorganization Act, and was designed for the purpose of expanding regular funding for SUD services. SUBG funds are primarily prioritized for individuals who are uninsured or underinsured, and help ensure that people who lack health coverage are connected with the appropriate treatment.[32] SUBG is essential in filling gaps in SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery.[33] It is used to supplement, but not supplant, Medicaid coverage, with funding typically reserved for Granite Staters who remain uninsured or whose insurance does not cover the cost of care.[34]

Under federal law, no more than five percent of the SUBG Block Grant can be used for administrative purposes, and at least 20 percent must be used for SUD prevention efforts.[35] In addition, states must adhere to maintenance of effort (MOE) requirements in order to receive federal grant dollars, which requires that states spend at minimum the average amount allocated during the prior two years.[36]

The SUBG is overseen by the State’s Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services (BDAS), which is responsible for coordinating SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery services across New Hampshire. SUD prevention in New Hampshire is primarily supported by Regional Public Health Networks (RPHNs), which help lead health promotion efforts and community outreach around substance misuse. The RPHN is comprised of ten regions across the state, with each city and town in New Hampshire falling within one of the region’s borders.[37]

Beyond the RPHN, the SUBG supports several other initiatives aimed at preventing substance misuse across the lifespan. The Referral, Education, Assistance, and Prevention (REAP) initiative supports older adults and their caregivers with aging challenges, including managing grief, loss, and stressors associated with life changes. Prevention efforts have also been expanded through school-based programming for high need communities, supporting several activities such as individual and group support, substance misuse education, and resources for parents.

Relative to SUD treatment funded by the SUBG, the DHHS typically contracts with service providers to deliver services ranging from withdrawal management, MAT, outpatient and intensive outpatient services, residential treatment, non-peer recovery support, and specialized services for pregnant women or mothers and their children, allowing for individualized care for people at different stages of recovery.

In addition to the standard SUBG, states received additional federal grants, commonly referred to as COVID-19 supplemental grants, to help support additional SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery efforts during a time of heightened need. In March 2025, an estimated $2.3 million in contracted but unspent COVID-19 supplemental funds were unexpectedly terminated by the federal government. While supplemental funds were not used towards SUD and mental health direct services, these grants supported several operational purposes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, including expanding trauma-informed training for first responders and health providers, as well as administrative assistance for Community Mental Health Centers working to become federally Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs).[38] These investments provided long-term benefits to behavioral health infrastructure, despite the end of the one-time investment.

State Opioid Response Grant

First established through the 2018 federal Consolidated Appropriations Act, the State Opioid Response (SOR) Grant was created in response to the ongoing opioid public health crisis to expand access to prevention, treatment, and recovery across the country. The SOR Grant program has gone through several changes and reauthorizations since its inception in 2018, with the most recent State Opioid Response Grant Authorization Act of 2021 reauthorizing the initiative until Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2027, or September 30, 2027.[39]

Unlike other federal funding streams to combat SUDs, these noncompetitive, 100 percent federal grants are reserved for OUDs, stimulant use disorders (StUDs), and any co-occurring disorders with other substances. Similarly to other federal grants, no more than five percent of funds can be spent on administration; however, up to two percent may be permitted for data collection. Outside of these restrictions, the federal government has provided flexibility to states to spend SOR funds on evidence-based practices that best fit the needs of their populations. These funds can be used to supplement, but not supplant, Medicaid or other federal funding, as providers are typically directed to bill Medicaid for eligible services first and utilize other funds to supplement coverage gaps.[40] From SFYs 2019 to 2025, approximately $140.5 million of SOR Grant funds were expended in New Hampshire.

In New Hampshire, SOR funds have been primarily used to establish and implement the State’s Doorways initiative. Through this program, Granite Staters can access services at any of the nine Doorways, located in hospitals and health centers across the state, and can be promptly connected to the appropriate level of SUD care. Doorways typically operate through a continuum of care model, linking prevention, treatment, and recovery services through one combined system.[41]

Since the beginning of the program in 2019, approximately 56,818 individuals have been served through Doorways, including people seeking direct services, as well as family members looking for information or support. As of 2024, around 16,920 people have received clinical evaluations at Doorways locations, while 28,127 have received treatment referrals for services. The largest increase in services, however, has been among the distribution of naloxone kits, a lifesaving overdose-reversal medication used to quickly reverse opioid overdoses. In 2024, approximately 38,388 naloxone kits were distributed through Doorways, an increase of more than 300.0 percent from the 9,190 kits distributed in 2019. From 2019 to 2024, approximately 147,606 naloxone kits have been distributed throughout Doorways’ implementation.[42]

While the Doorway system has been vital for connecting people with prevention, treatment, and recovery services, regional differences across New Hampshire may pose challenges for access. All Doorways are located in or around the state’s larger communities, which may create barriers to access for Granite Staters in rural areas. The Doorways at Androscoggin Valley Hospital in Berlin, Regional Healthcare in Littleton, and Concord Hospital in Laconia are the only locations serving the North Country, White Mountains, and Lakes Region.[43] Residents traveling from larger communities in these areas, such as Conway and Colebrook, would need to travel an hour or more to access in-person services at Doorways. People accessing services at these locations, particularly in Berlin, may also experience barriers due to longer waiting times. According to the most recently published Doorway program evaluation from September 2023, patients at Berlin’s Doorway location may have had to wait up to two weeks to access medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), while all other locations provided services or referrals within 24-72 hours.[44] Remote locations may also experience staffing shortages, as the evaluation recommends expanding training and support to account for any staffing turnover.[45]

Other Federal Grants

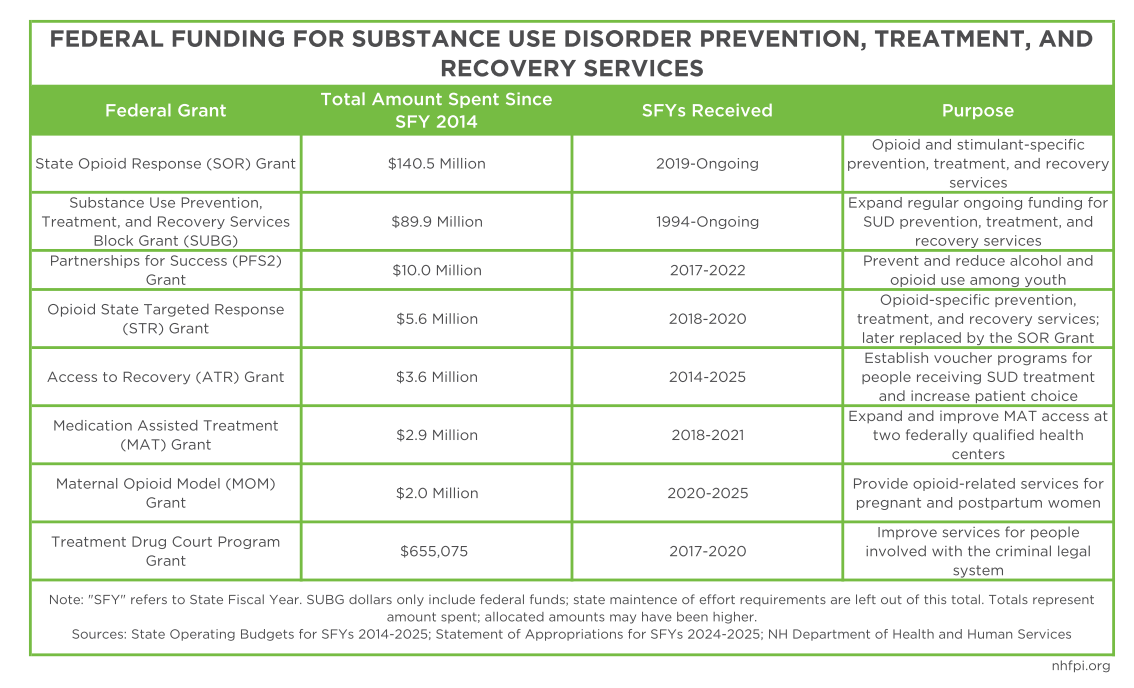

In addition to the SUBG and the SOR Grant, the federal government has supplied various smaller grants to help support SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery. From State Fiscal Years (SFYs) 2014 to 2022, the NH BDAS and Division of Medicaid Services administered and oversaw six individual federal grants, including the PFS2 Grant, the Opioid STR Grant, the Treatment Drug Court Grant, the MAT Grant, the ATR Grant, and the MOM Grant. When combined, spending across these six grants totaled $24.8 million.

During the SFYs 2014-2015 State Budget biennium, approximately $3.6 million was spent on the Access to Recovery (ATR) Grant to establish voucher programs for people receiving SUD treatment, allowing for patient choice among certain services. More recently, from SFYs 2017 to 2022, the Partnerships for Success (PFS2) Grant provided $10.0 million in expenditures to help prevent and reduce alcohol and opioid use among youth and young adults, reaching approximately 27,000 children each year.[46] The Opioid State Targeted Response (STR) Grant, later replaced by the SOR Grant, supplied approximately $5.6 million to New Hampshire from SFYs 2018 to 2020. This grant was used to support several opioid-specific prevention, treatment, and recovery services, including MAT expansion and peer support services for pregnant and postpartum women, as well as naloxone distribution among people transitioning back into the community following incarceration.[47] From SFYs 2018 to 2021, approximately $2.9 million was allocated in MAT Grant dollars to expand and improve MAT access at two federally qualified health centers in Manchester and Nashua.[48] Between SFYs 2017 to 2020, the Treatment Drug Court Program Grant provided $655,075 to help improve services for Granite Staters involved with the criminal legal system due to substance-related crimes by increasing staff training, case management, and MAT.

Finally, from SFYs 2020 to 2025, approximately $2.0 million was allocated under the Maternal Opioid Model (MOM) Grant. New Hampshire is one of only seven states to receive these specialized funds. Operated by the Elliot Health System, this program provided OUD services for pregnant and postpartum women, including inpatient and outpatient treatment, access to MAT, case management services including food and housing assistance, and perinatal and postpartum care, such as OB/GYN and midwife services. The intended outcome of the MOM Grant was to establish an improved system of care to provide early intervention for mothers with OUD and their infants, leading to improved health outcomes and long-term cost savings.[49] One recent study analyzing 2010-2020 data among Medicaid-eligible mothers in Alabama found that newborns diagnosed with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) acquired an estimated $17,921 in additional health care costs compared to newborns without NOWS.[50] While the MOM Grant only operated for five fiscal years, continued investment for pregnant and postpartum mothers could lead to decreased health care costs in the long-term.

State Funding and the Governor’s Commission

The Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention Fund (“the Fund”), formerly known as the Alcohol Abuse, Prevention, and Treatment Fund, was established through RSA 176-A:1 in 2000 to streamline State funding to address alcohol and substance misuse in New Hampshire. State law required that each fiscal year, five percent of the State Liquor Commission’s gross liquor sale revenue is deposited into the Fund, creating a dedicated and stable funding source for SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery.[51] However, the Fund was often not resourced at that level, with temporary laws diverting funding elsewhere.[52] Unlike most other SUD funding sources, the Fund has historically been unencumbered from restrictions, which has provided flexibility for policymakers to utilize these funds to address emerging issues.

The Fund is overseen by the Governor’s Commission on Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention, which is responsible for authorizing funding uses and developing a comprehensive plan for ongoing SUD prevention in New Hampshire. Formerly called the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Other Drugs, the Commission is comprised of legislators, State officials, and members of the public, including health care providers and people with lived experience; it aims to promote collaboration across various entities, helping to bridge gaps between the State and community.[53]

Second to the State’s share of Medicaid funding, the Governor’s Commission remains one of the largest sources of State funding for SUD prevention, treatment, and recovery. From SFYs 2014 to 2025, approximately $74.3 million was expended through the Commission, although allocations have become more prominent over the last several years. During SFY 2025, the Commission spent approximately $10.9 million, more than ten times the $1.1 million spent during SFY 2014.[54]

During SFY 2024, more than one quarter (26.3 percent, $2.6 million) of the Governor’s Commission allocations were spent on recovery services, including peer support, recovery housing services, and the Recovery Friendly Workplace initiative, which provides workplace support for people in SUD recovery. Through ten Recovery Community Organizations (RCOs), the largest recipient of recovery-based funds, 6,769 people received individual peer support during SFY 2024. A nearly equal percentage (25.7 percent, $2.5 million) of Commission funds were distributed for prevention efforts, including youth and young adult prevention through school and community-based programming, support for collegiate students, health promotion and resource dissemination, programs specifically targeting Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), juvenile court diversion, and New Hampshire’s Synar Program, which aims to reduce nicotine access among youth.[55]

Around $1.9 million, or 19.0 percent, of the Governor’s Commission allocations were used towards care coordination and behavioral health integration, helping to bridge gaps across the SUD continuum of care. The Community Housing Program served 191 participants during SFY 2024, providing housing support for Granite Staters re-entering the community on parole or probation, as well as people participating in a drug court program. Care coordination funds are also used to support the integration of SUD care within the full health care system, with approximately seven hospitals participating in improvement projects around peer recovery, naloxone dispensation, and other critical SUD services.

Approximately $1.4 million, or 13.9 percent, of funds were used for treatment services among ten contracted organizations across New Hampshire. These funds are primarily used among people unable to obtain SUD care, such as those who are experiencing homelessness, or are uninsured or underinsured. During SFY 2024, around 590 people received treatment for alcohol use disorder, 582 for OUD, 380 for amphetamine use disorder, and 154 for cannabis use disorder.

About $1.0 million, or 10.5 percent, of funds were used for data monitoring and professional development, including program evaluation, analyses of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), prevention certification for providers, and workforce trainings. Only a combined $172,000, or 1.8 percent of the Commission’s SFY 2024 expenditure, was spent on family peer support and harm reduction efforts, such as the distribution of naloxone, test strips, and syringe disposal.

Opioid Settlement Funds

In 2021, states across the country began receiving settlement funds resulting from a series of lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and retailers for their role in the ongoing opioid epidemic. These funds, commonly referred to as opioid abatement funds in New Hampshire, are intended to help provide support and restitution for communities who face public health implications and societal harms from opioid misuse.[56] Most settlement funds received by the states are reserved for OUD prevention, treatment, and recovery, although specific spending uses differ by settlement agreement. At least 70 percent of National Settlement funds, or the first major joint lawsuit, must be used for opioid remediation efforts.[57]

In order to maximize the total amount of money that the State receives, New Hampshire encouraged counties and municipalities to sign onto the lawsuits, with 23 out of 47 of the State’s invited subcommunities choosing to participate. Among each settlement disbursement, a total of 15 percent is allocated across the 23 subcommunities, with payments based on county and municipal population size. As of September 2025, New Hampshire has received approximately $99.3 million in opioid settlement funding, with more than $14.5 million distributed to subcommunities as of November 2024.[58] Of this amount, municipalities and counties have reported only spending a combined $3.7 million (25.5 percent) as of 2024. Spending uses on the local level include providing MAT and case management to people who are incarcerated, training providers and law enforcement, hiring social workers and case managers at correctional departments and police stations, and establishing or helping to implement recovery centers, among other uses.[59]

All remaining settlement funding, outside of subcommunity distributions, is deposited into New Hampshire’s Opioid Abatement Trust Fund, which is overseen by the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission responsible for establishing funding priorities and ultimately deciding how funding will be used. The Advisory Commission is comprised of lawmakers, state officials, county and municipal designees, public health practitioners and providers, and law enforcement officials, although only one seat is reserved for someone with lived or shared experience.[60]

Among statewide abatement funds, New Hampshire has spent approximately $40.3 million and obligated $59.0 million of the settlement money received as of September 2025.[61] These funds have been used towards contracts for services, including peer recovery support, youth prevention, support for people involved with the criminal legal system, workforce recruitment and retention, recovery housing, transportation services, and harm reduction initiatives. During SFY 2024, the DHHS estimated that more than 7,440 Granite Staters received services through contracted organizations. Outside of contract spending, new Abatement Fund uses were added to the SFYs 2026-2027 State Budget biennium, including $10 million reserved for shelters serving people experiencing homelessness who are also experiencing an OUD, as well as $3.5 million for law enforcement overtime pay with the Granite Shield Substance Abuse Program.[62]

As of September 5, 2025, $14.4 million remained unobligated in the Opioid Abatement Trust Fund, after accounting for contracts, positions, and other projects to be supported by this funding.[63] Reflecting data from January 2025, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that New Hampshire will receive approximately $168.2 million in future settlement payments.[64] The Opioid Abatement Trust Fund’s continuing balance and large estimated annual payments could allow for more spending flexibility across the state.

Settlement Funding in Other States

Several states have used their settlement funds towards implementing and enhancing harm reduction strategies, including improving access to MAT, naloxone, syringe services, and mobile outreach programming. Research suggests that harm reduction provides long-term public health benefits, as well as associated cost-savings for the health care system. These services can reduce drug-related overdoses and decrease the likelihood of negative health outcomes from use, such as contracting infectious diseases from unclean syringes. Harm reduction models also aim to meet people at their stage of use or recovery, often providing education and resources for people seeking help.[65] Harm reduction services, particularly MAT, can also help keep people remain in the workforce while they are actively receiving treatment.

In New York, the state has prioritized quicker access to buprenorphine, a type of MAT prescribed for OUD, through its Buprenorphine Assistance Program (BUPE-AP), an initiative that provides same-day access and services by expanding the number of prescribing physicians and reducing prior authorization structures that may delay care.[66] Following the implementation of New York’s BUPE-AP in 2016, the number of providers authorized to prescribe buprenorphine increased by approximately 68.1 percent.[67] Buprenorphine has historically been prescribed less frequently than other FDA-approved MAT medications, including methadone and naltrexone, largely due to more stringent provider restrictions.

In Rhode Island, settlement funds have also been used to improve harm reduction, including the establishment of a Harm Reduction Center Pilot Program, permitting one of the country’s first safe injection sites, second only to New York City.[68] The Arkansas Mobile Opioid Recovery (ARMOR) initiative, the High Rockies Harm Reduction program in Colorado, and several other mobile outreach programs across the country received settlement funds to provide care for people in their communities without needing to travel long distances. In Michigan, the state has used funds to expand its Syringe Service Programs (SSPs), an initiative providing sterile injection supplies, infectious disease testing, and referrals to SUD treatment.[69] Despite successes among evidence-based SSPs, such services may be limited due to state and local regulations. In New Hampshire, SSPs are only permitted if they are self-funded, eliminating the use of state and federal funds, and can only be administered by certain providers.[70]

Outside of harm reduction strategies, states have also utilized funds to expand the behavioral health workforce. Since the state began receiving settlement dollars in 2021, California has invested more than $197.0 million towards its Behavioral Health Workforce Development initiative, with approximately 288 organizations receiving funds to help recruit and retain behavioral health providers. The Mentored Internship Program, part of the larger initiative, aims to attract students and young professionals to the fields of social work and public health, helping to grow the SUD workforce across the state.[71]

Several states have used their funds to make structural investments, as resources such as safe and affordable housing and access to transportation can better equip people to remain engaged in SUD treatment and recovery. Building on their Housing First Program designed to provide rental assistance with limited barriers to entry, Indiana has used abatement funding to expand the Division of Mental Health and Addiction (DMHA)’s certified recovery residencies, including a variety of recovery and sober living homes.[72] More recently, Connecticut announced $58.6 million for the Housing as Recovery initiative, a program providing stable housing and recovery support for an estimated 500 people annually.[73] On the local level, Philadelphia has used funds to partner with the New Kensington Community Development Corporation (NKCDC), providing rental assistance and home repairs to help people regain housing stability and remain in their homes.[74] Finally, Michigan’s Benzie County has used abatement funds towards their public transportation system, allowing people on parole or probation to access services and attend required meetings with parole officers.

The Future of Funding for New Hampshire

While Medicaid has remained the largest funding stream for SUD treatment, pending state and federal changes could impact public health coverage for Granite Staters. Medicaid work requirements, included in both the new federal reconciliation law and new SFYs 2026-2027 State Budget, would require many Medicaid Expansion adults to provide documentation to show work or participation in an eligible community engagement activity in order to obtain health coverage. Both the new federal reconciliation law and the current State Budget also implement cost shares for certain Granite Advantage adults, requiring monthly premiums on the state level and copayments for services on the federal level.[75]

While it is unclear how state and federal Medicaid changes may interact, early research suggests that changes included in the federal reconciliation law could result in many people losing health plan coverage. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) estimated that federal Medicaid spending in New Hampshire will decline by $2.3 billion, or 15 percent, over the next ten years.[76] By 2034, an estimated 10 million more people across the country will be uninsured as a result of the federal reconciliation law, according to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office.[77]

While Expansion adults engaged in SUD treatment are exempt from new federal law changes, differing state interpretations of the law, as well as difficulties with exemption paperwork and redeterminations could mean coverage losses for people in treatment and recovery.[78] According to early national research, an estimated 156,000 people could lose access to MAT because of the new federal reconciliation law, leading to around 1,000 more opioid deaths annually.[79]

In addition, changes in funding for the Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention Fund were enacted as part of the SFYs 2026-2027 State Budget. Approximately $19.0 million was allocated to the Fund across the two fiscal years, a decline of $1.7 million (8.4 percent) from the actual amount spent of $20.7 million during the prior budget biennium.[80] The new Budget also removes the automatic transfer of five percent of liquor revenue to the Fund, with appropriations in the biennium funded with General Fund dollars. This change could compromise funding for the Governor’s Commission of Addiction, Treatment, and Recovery if General Funds are not available or insufficient in future biennia.

Despite an increased investment in SUD prevention, treatment and recovery, significant service gaps remain for Granite Staters. In 2022-2023, nearly three out of four, or 74.4 percent, of New Hampshire residents age 18 or older who needed SUD treatment did not obtain it.[81] Despite an increase in prevention strategies and harm reduction services over the last decade, ongoing challenges in accessing treatment suggest that continued obstacles remain, including workforce shortages, regional accessibility disparities, insurance and coverage limits, housing instability, and other structural challenges for accessing treatment. Without continued investment and innovation, the progress made in reducing drug-related deaths could stall, or even reverse, putting more families and communities at risk.

*Opioid settlement funding totals were updated on September 30, 2025, after the initial Report publication, to reflect newly obtained data.

Endnotes

[1] See the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Traffic Fatalities by State.

[2] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2025 Report, page 1.

[3] Substance use is defined as “the use of selected substances, including alcohol, tobacco products, illicit drugs, inhalants, and other substances that can be consumed, inhaled, injected, or otherwise absorbed into the body with possible dependence and other detrimental effects.” Substance abuse is defined as “a pattern of compulsive substance use marked by recurrent significant social, occupational, legal, or interpersonal adverse consequences, with nine associated drug classes: alcohol, amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidines, and sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics.” Substance use disorder is defined as “the medical term used to describe a pattern of using a substance (drug) that causes significant problems or distress.” Substance dependance is defined as “the medical term used to describe use of drugs or alcohol that continues even when significant problems related to their use have developed.”

[4] See the U.S. Census for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Vital Signs, Drug Overdose Deaths Rise, Disparities Widen, last updated July 2022.

[5] For more information on the social determinants of health (SDOH), see the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Determinants of Health (SDOH).

[6] See Fardone, Montoya, Schackman, and McCollister, Economic benefits of substance use disorder treatment: A systematic literature review of economic evaluation studies from 2003 to 2021, Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment.

[7] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2025 Report, page 18.

[8] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2025 Report, page 1.

[9] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2025 Report, page 18.

[10] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER and Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts.

[11] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WONDER.

[12] Crude mortality rates calculated using the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts and the U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates Program, State Population Totals, 2020-2024. Numbers are not final in the CDC WONDER Database, and may not reflect actual crude mortality rates for 2024.

[13] For national mortality rates by racial and ethnic group, see the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WONDER. For national population counts for 2024, see the U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates Program, National Population by Characteristics, 2020-2024. Mortality rates by racial and ethnic group are unavailable for New Hampshire due to small population sizes.

[14] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics, Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2003-2023. For more information on the impact of the opioid epidemic on indigenous communities, see The Brookings Institution, Fentanyl’s Impact on Native American Communities and Paths to Recovery and The Impact of Fentanyl on American Indian and Alaskan Native Communities.

[15] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2025 Report, page 18.

[16] See the NH Drug Monitoring Initiative, April 2025 Report, page 4.

[17] For more information on SUD services in rural areas, see the University of New Hampshire’s June 19, 2018 research brief, The Opioid Crisis in Rural and Small Town America.

[18] For more information on the intersection between State and federal funds in New Hampshire, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Other Drugs, Action Plan Strategy Funding Sources Crosswalk, State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2025 Update.

[19] All funding data, outside of Medicaid, was compiled using a combination of Operating State Budgets, Statements of Appropriations, and Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee items spanning from 2013 to 2025. Even-numbered year data was taken from the spent column from the Governor’s Operating Budget for each associated year (e.g. SFY 2024 data was taken from the Governor’s Operating Budget for SFYs 2026-2027). Odd-numbered year data was taken from Statements of Appropriations acquired through the Office of the Legislative Budget Assistant. Funding for each SFY was divided evenly into two parts to reflect the calendar year; actual appropriations by calendar year may differ. All funding represents actual spent amounts; budgeted or adjusted authorized amounts may differ.

[20] All opioid abatement topline numbers were taken from the Opioid Abatement Trust Fund and Advisory Commission, Annual Report, State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024, page 23. City and county spends were compiled from the Commission’s webpage, Distribution of Funds. Note that not every city or county submitted reports each year, so the total amount spent may be incomplete.

[21] See the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Behavioral Health Services. For more information on Medicaid’s role in SUD services, see The Brookings Institution’s February 2025 publication The Role of Medicaid in Addressing the Opioid Epidemic.

[22] For more information on the impact of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s January 2023 Issue Brief, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire. For federal poverty guidelines for 2025, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2025 Poverty Guidelines for the 48 Contiguous States.

[23] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services, New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography, July 2025 Report, page 2.

[24] All Medicaid funding data in this Report was acquired through a data request from the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medicaid Services. Note that MCO dollars are provider payments and not actual federal and State paid dollars. MCO capitation rates are the true payments and cannot be precisely connected to specific services. Emergency Department visits with a primary opioid diagnosis were excluded, as there was an insignificant amount of these Other Outpatient Services present in the data. Claims data between January-June 2013 was not available in the data source; paid amount was approximated based on population and dollars paid between July-December 2013.

[25] See the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Medicaid is Key to Building a System of Comprehensive Substance Use Care for Low-Income People, Figure 2.

[26] See the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage in the United States, Table S2701, 1-Year Estimates for 2013-2024.

[27] For a list of full SUD benefits in New Hampshire, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Benefit for Medicaid Recipients. Dates for full continuum coverage were supplied by the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Division for Medicaid Services.

[28] See the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Access to Substance Use Treatment in Medicaid. For more information on the nine levels of SUD care, see the American Academy of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). These ASAM levels of care allow for flexible service options to meet a person’s treatment and recovery needs. Level 1 includes outpatient therapy, medically managed outpatient services, and long-term recovery monitoring. Level 2 encompasses intensive, high-intensity, and medically managed intensive outpatient services. Level 3 includes clinically managed low-intensity, clinically managed high-intensity, and medically managed residential treatment. Level 4 encompasses the most intensive SUD care, including 24/7 medically managed inpatient treatment.

[29] All Medicaid caseload data was acquired through a data request from the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medicaid Services. Note that annual caseloads represent unduplicated data.

[30] See the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, T-MSIS Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Data Book, Treatment of SUD in Medicaid, 2021, page 36.

[31] See The Brookings Institution, The Role of Medicaid in Addressing the Opioid Epidemic, February 2025.

[32] For more information on the SUBG, see the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (SUBG). For more information on the SUBG in New Hampshire, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant.

[33] For more information, see the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), The CBHSQ Report, The Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant is Still Important Even with the Expansion of Medicaid, January 2016.

[34] See the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), Federal and State Funding Sources for Substance Use Disorder Treatment, Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (SUBG).

[35] See the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), Substance Use Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery Services Block Grant (SUBG), Primary Prevention.

[36] For more information on maintenance of effort (MOE) requirements, see the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), A Primer on Maintenance of Effort Requirements, 2020, and the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Behavioral Health (DBH), DHHS Budget Briefing Book, page 5.

[37] For more information on SUD prevention, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Misuse and Prevention.

[38] For more information on terminated pandemic-related funding, see NHFPI’s May 2025 blog, Sudden End to Federal Pandemic-Related Grants Leaves Unplanned Service Gaps.

[39] For more information on the State Opioid Response (SOR) Grant in New Hampshire, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, State Opioid Response Grant.

[40] See the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), Federal and State Funding Sources for Substance Use Disorder Treatment, State Opioid Response (SOR) Grants.

[41] For more information on services, see the State’s website for The Doorway.

[42] See the State’s website for The Doorway, Data Metrics. Note that data was taken from the most recently available report for each year, as the data are updated over time.

[43] For Doorway locations, see the State’s website for The Doorway.

[44] See The Doorway Program Evaluation, Final Report, September 2023, page 99.

[45] See The Doorway Program Evaluation, Final Report, September 2023, page 59.

[46] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Budget Briefing Book, page 183.

[47] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Budget Briefing Book, page 168.

[48] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Budget Briefing Book, page 185.

[49] For more information on the MOM Grant, see the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model and The Elliot, Substance Use Disorder Services, Maternal Opioid Misuse Grant Program.

[50] See Jenkins, Hudnall, and Hanson, Cost of Care for Newborns with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome in a State Medicaid Program.

[51] See RSA 176-A:1.

[52] For examples of prior law changes impacting the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

[53] For more information on the Governor’s Commission, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, The Governor’s Commission on Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention.

[54] Even-numbered year data was taken from the spent column from the Governor’s Operating Budget for each associated year (e.g. SFY 2024 data was taken from the Governor’s Operating Budget for SFYs 2026-2027). Odd-numbered year data was taken from Statements of Appropriations acquired through the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant.

[55] All Commission expenditures were drawn from the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee’s Agenda for August 16, 2024 and represent State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024 expenditures as of June 30, 2024. Expenditures for the NH Harm Reduction Coalition were taken from the Committee’s Agenda for September 13, 2024, as expenditures were still pending in August. Organizations were grouped into a category based on the Governors’ Commission SFY 2024 Annual Report. Organizations not represented in the Report were grouped into the “other/unknown” category. Caseloads were drawn from the SFY 2024 Annual Report where available.

[56] For more information on the suggested guiding principles for settlement funds, see the Johns Hopkins’ School of Public Health, The Principles for the Use of Funds from the Opioid Litigation.

[57] See the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), Understanding Opioid Settlement Spending Plans Across States: Key Components and Approaches, Requirements for Opioid Settlement Spending in the National Settlement Agreement.

[58] Opioid settlement revenue and balances were obtained through updated data from the NH Department of Health and Human Services, as well as the Opioid Abatement Commission. The amount distributed to subcommunities reflects data in the Opioid Abatement Commission’s SFY 2024 Report, page 24. New data for subcommunity distributions was unavailable.

[59] Subcommunity spent amounts are taken from the Commission’s webpage, Distribution of Funds. Note that not every city or County submitted reports each year, so the total amount spent may be incomplete.

[60] For more information on the Commission, see the NH Department of Health and Human Services, NH Opioid Abatement Trust Fund and Advisory Commission. For more information on Committee members in other states, see the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), Payback: Tracking Opioid Cash, Meet the People Deciding How to Spend $50 Billion in Opioid Settlement Cash, last updated June 2024.

[61] Opioid settlement expenditures and obligations were obtained through updated data from the NH Department of Health and Human Services, as well as the Opioid Abatement Commission.

[62] See NHFPI’s July 2025 Report, The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2026 and 2027.

[63] Opioid Abatement Fund balances obtained through updated data from the NH Department of Health and Human Services, as well as the Opioid Abatement Commission. Obligations reflect money reserved for contracts, not spent dollars.

[64] See the Kaiser Family Foundation, For Opioid Victims, Payouts Fall Short While Governments Reap Millions, Opioid Settlement Payouts to State and Local Governments.

[65] For more information on harm reduction, see the Johns Hopkins’ School of Public Health, What is Harm Reduction?

[66] See the State of New York, Department of Health, Buprenorphine Access Initiative.

[67] See the State of New York, Department of Health, SUD Implementation Plan, January 2024, page 186.

[68] For more information on Rhode Island’s pilot program, see Project Weber/Renew and the State of Rhode Island’s factsheet.

[69] See the State of Michigan, Health and Human Services, Harm Reduction and Syringe Service Programs.

[70] For more information about syringe services in New Hampshire, see the NH Harm Reduction Coalition.

[71] See the CA Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Community Services Division, Behavioral Health Workforce Development.

[72] See the State of Indiana, IHCDA Announces Rental Housing for Persons with Substance Use Disorder and Housing First Program.

[73] See the State of Connecticut, Press Release, January 2025.

[74] See Co-Creating Kensington, Opioid Settlement Funds.

[75] For more information on federal Medicaid changes, see NHFPI’s August 2025 Issue Brief, New Federal Reconciliation Law Reduces Taxes, Health Access, and Food Assistance Supports for Granite Staters. For more information of state Medicaid changes, see NHFPI’s July 2025 Report, The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2026 and 2027.

[76] See the Kaiser Family Foundation, Allocating CBO’s Estimates of Federal Medicaid Spending Reductions Across the States: Enacted Reconciliation Package, July 2025.

[77] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, estimate compiled to accompany August 11, 2025 letter to members of Congress.

[78] For more information of H.R. 1’s impact for SUD services, see the Kaiser Family Foundation, Implications of Potential Federal Medicaid Reductions for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic and Implications of Medicaid Work and Reporting Requirements for Adults with Mental Health or Substance Use Disorders.

[79] See the University of Pennsylvania and Boston University, Estimated Overdose Deaths Due to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, July 2025.

[80] Allocations to the Governor’s Commission for SFYs 2026-2027 were taken from the Operating Budget. Actual spent amounts for SFY 2024 were taken from the Governor’s Operating Budget for SFYs 2026-2027. Actual spent amounts for SFY 2025 were taken from the Statement of Appropriations for SFY 2025, acquired from the Legislative Budget Assistant.

[81] See the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Interactive NSDUH State Estimates for New Hampshire, 2022-2023. Note that percent not in treatment includes people not ready to receive treatment, as well as those who could not access services due to constraints with cost and accessibility.