New Hampshire has a historic opportunity to support both immediate and long-term economic prosperity and help build an equitable recovery that fully includes struggling Granite Staters. About one in four New Hampshire adults, or approximately a quarter of a million people, found it somewhat or very difficult to pay for usual household expenses in early January 2022.[1] Resources are available to these Granite Staters through assistance programs, including new and temporary federally-funded initiatives designed to help respond to evolving challenges. Public benefit navigators could help individuals and families in New Hampshire who are experiencing prolonged financial hardship access available support, and the State has flexible federal resources that may be used for this purpose. Research suggests key programs designed to provide assistance to individuals and families with low incomes effectively boost economic growth. Granite Staters, and their local economies, would benefit from additional targeted federal aid coming to New Hampshire.

New Hampshire has significant flexible, temporary federal funds available through the American Rescue Plan Act, which provide a substantial opportunity to help build a strong and equitable economic recovery. Key policy initiatives with stimulative economic impacts also direct resources to Granite Staters with the highest levels of need. Enrolling eligible people in these programs both helps those Granite Staters make ends meet and leverages additional federal funds, stimulating local business activity and the economy.

Public benefit navigators can help individuals and families apply for and access assistance for which they are eligible, reducing barriers to enrolling in public assistance programs such as tax credits or direct aid for housing or child care. The new, expanded, and temporary programs associated with the policy responses to the pandemic may have unique requirements for enrollment. Eligibility has recently changed for several programs as well. Research suggests key assistance programs appear to reach many fewer people than are eligible in New Hampshire. Public benefit navigators could help guide Granite Staters through the changes and complexities of these programs and help close the gap between enrollment and eligibility.

Benefit navigators could provide targeted help to populations previously unreached or underserved by assistance programs. People with low incomes and historically disadvantaged groups have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. These New Hampshire residents may be able to more fully participate in the workforce and the economic recovery with additional support to access existing services, including people in under-resourced communities and Granite Staters with limited English proficiency. The beneficial impacts of a one-time investment in navigators may also mitigate the damage of future economic downturns on more vulnerable communities and on the overall economy. Key assistance may also provide long-term and intergenerational benefits, particularly those that have been shown to improve the health and development of children.

This Issue Brief provides insight into the permitted uses of the flexible federal funds available to state and local governments, and reviews assistance programs available to individuals and families that have been created or modified due the pandemic. The Issue Brief also examines the potential positive impacts of deploying flexible federal funds for public benefit navigators to help Granite Staters access aid, and describes the benefits and overall economic stimulus provided by key assistance programs.

Flexible Federal Aid to Build an Inclusive Recovery

Federal policymakers provided state and local governments with a unique and historically substantial opportunity to invest in creating an inclusive recovery and widespread economic well-being. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocated $994.56 million in relatively flexible funds provided to the State of New Hampshire, not including the $462.3 million in similarly flexible funds provided to counties, cities, and towns in New Hampshire. These funds, named the Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Funds (CSFRF), can be used for a wider variety of purposes compared to most other funds deployed to governments by ARPA. The federal government, through the U.S. Treasury Department, has provided initial interim and final rules and placed certain limitations on the use of these resources.[2]

The U.S. Treasury Department identified four broad areas for eligible uses of the CSFRF:[3]

- “Respond to the far-reaching public health and negative economic impacts of the pandemic, by supporting the health of communities, and helping households, small businesses, impacted industries, nonprofits, and the public sector recover from economic impacts”

- “Provide premium pay for essential workers, offering additional support to those who have and will bear the greatest health risks because of their service in critical sectors”

- “Replace lost public sector revenue, using this funding to provide government services up to the amount of revenue lost due to the pandemic”

- “Invest in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure, making necessary investments to improve access to clean drinking water, to support vital wastewater and stormwater infrastructure, and to expand affordable access to broadband internet”

In the initial rule governing use of these funds, the U.S. Treasury Department specifically:

- noted that the CSFRF can help address “the systemic public health and economic challenges that may have contributed to more severe impacts of the pandemic among low-income communities and people of color.”[4]

- encouraged recipient governments “to consider funding uses that foster a strong, inclusive, and equitable recovery, especially uses with long-term benefits for health and economic outcomes.”[5]

U.S. Treasury Department rules give recipients of these funds, including the State of New Hampshire as well as counties and municipal governments, a substantial range of eligible uses to support families, businesses, and communities that were negatively impacted by the COVID-19 public health emergency. Recipients have broad latitude, within certain parameters, to use these funds to address the negative economic impacts associated with the pandemic as well.[6]

U.S. Treasury Department rules documents also suggest certain uses, providing detailed examples of permissible deployment of these funds and encouraging recipients to undertake certain activities. Rules permit recipients to use funds for addressing both the direct and certain indirect health impacts of the pandemic, including COVID-19 testing and prevention, vaccination programs, and behavioral health needs exacerbated by the pandemic, such as substance misuse and mental health treatment. Economic assistance could come in the form of direct assistance to households and families, small businesses, nonprofits, and impacted industries. Assistance to households could include, but is not limited to, cash or food assistance, emergency housing assistance, home repairs or weatherization, internet access assistance, paid sick or family leave, child care, employment assistance, and assistance accessing public benefits. The U.S. Treasury Department did limit the use of funds for certain general infrastructure projects, but recipients can use these funds for a relatively wide array of water and sewer infrastructure projects, as well as broadband internet upgrades meeting certain specifications and targeted at underserved communities.[7]

Relative to the decision processes for determining the uses of these funds, the U.S. Treasury Department urged State and local governments to engage their constituents and communities in developing the plans for the use of these funds.[8]

Federal Funds May Support Public Benefit Navigators

The U.S. Treasury Department expressly permitted the use of CSFRF to help connect people with public benefits and services, including through funding public benefit navigators.[9] With hundreds of millions of CSFRF dollars remaining available statewide, New Hampshire’s State government and local governments could commit resources to public benefit navigators to support individual Granite Staters and the recovery overall.[10]

The initial rule provided by the U.S. Treasury Department, which the final rule expanded upon, identifies that State and local governments may use the CSFRF to “facilitate access to resources that improve health outcomes, including services that connect residents with health care resources and public assistance programs and build healthier environments;” the Department specifically suggests “public benefit navigators to assist community members with navigating and applying for available Federal, State, and local public benefits or services.”[11] The rule also suggests funding community health workers to help people “access health services and services to address the social determinants of health;” the initial rule identifies the social determinants of health as the social and environmental conditions that affect health outcomes, such as economic stability, health care and education access, social context, and both neighborhoods and the built environment.[12]

CSFRF dollars can also be used to help people access physical and behavioral primary health care and preventative medicine.[13] These funds can also be used for improving the efficacy of both economic relief and public health programs through targeted outreach.[14]

Federal legislation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has both established new programs and expanded existing assistance programs. Some of these programs are direct federal assistance to individuals, while others are administered by state-level entities. The myriad of public assistance programs, including these new and temporarily expanded programs, provide a substantial opportunity to bolster household finances, help generate economic activity for local businesses, and promote overall well-being. However, accessing these services is often complex, and many people in need may not know how to enroll in these programs, may not be aware that they are eligible, or may not know the services exist. Nearly all the enhanced programs require action on the part of individuals to fully access benefits.

Public benefit navigators can help connect individuals with services and programs for which they are eligible. Under enrollment in public assistance programs is a persistent challenge; closing the gap between the number of Granite Staters eligible for public benefits and the number enrolled could help enhance upward mobility and support the overall recovery from the pandemic.[15] Many households that were previously ineligible for benefits may have been made eligible by the negative economic shock of the pandemic, by the expansion of program eligibility in response to the pandemic, or both.[16] Helping ensure Granite Staters are accessing resources for which they are eligible can have both short- and long-term benefits, particularly relative to children’s development.[17]

Critically, public benefit navigators can help build a more equitable economy by helping historically underserved populations access resources, supporting upward mobility. People identifying as members of a racial or ethnic minority population in New Hampshire, Granite Staters who do not speak English or have limited English proficiency, and individuals and families with low incomes entered the pandemic facing certain financial and systemic disadvantages; these individuals and families may substantially benefit from targeted investments to avoid falling behind in the economic recovery.[18] Funding navigators and existing organizations to specifically reach underserved communities, as well as individuals and families who have faced prolonged financial hardship, to help them access available resources and reduce the risk of them falling behind during and after the COVID-19 crisis.[19]

Connecting Granite Staters to services in the short- and medium-terms can both address immediate needs and provide long-term benefits. The CSFRF can be used through the end of 2026, and funds unused at the end of 2026 must be returned to the federal government.[20] During that time period, public benefit navigators funded by the CSFRF can directly connect people with new, expanded, or temporary services to alleviate immediate challenges, and can also teach people how to access ongoing public services and resources that those individuals and families can access later as needed.

Many nonprofit organizations, particularly community action agencies and charitable tax preparation assistance efforts, as well as certain state and local government staff are employed in various navigator roles, often focused on specific programs.[21] For example, the State of New Hampshire has recently expanded contracts to support Family Resource Centers with a combination of State General Fund dollars and federal funds to boost certain navigator assistance to people, with approximately $1.855 million in funding to be used before June 2023.[22] Available flexible federal funds could be used to both complement and supplement ongoing efforts, and to fund new initiatives with longer timelines, to reduce under enrollment in programs among Granite Staters in need.

Targeted Assistance Policies Boost the Economy

Key public assistance programs can help spur economic growth, providing a positive return on investment in the broader economy. Both independent and government research, including analyses conducted by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, show that policies to support the resources of households with lower incomes are more likely to boost the economy than policies that provide assistance or resources to people with higher incomes.[23]

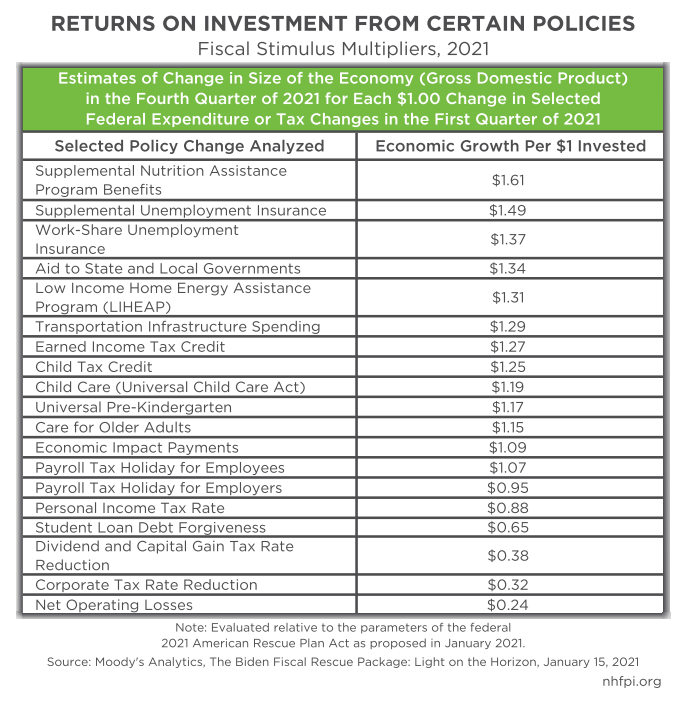

Research from Moody’s Analytics published in January 2021 projected the amount of economic growth by the last quarter of 2021 resulting from a federal spending or revenue policy change in the first quarter of 2021.[24] This analysis also indicated the policies that provide support to households with lower incomes were more effective economic stimulus than most other policy options examined, while reducing taxes for businesses or on investment income provided limited economic stimulus per dollar invested.[25]

Many of the policies examined by Moody’s Analytics in early 2021 were either enacted directly or modified and included directly in ARPA, which passed in March 2021. ARPA established many of the temporary policies currently allowing more benefits to flow to individual Granite Staters and help the local economy.[26]

Program Enrollment May Guide Other Resources

When enrollment in public assistance programs more accurately reflects community needs, other resources may be more effectively directed to communities with the greatest need.

For example, if public benefit navigators help students and their families enroll in free and reduced-price school meal programs, school districts may receive more resources to teach those children. The State’s education funding formula relies on free and reduced-price meal enrollment as an indicator of local poverty, and uses that indicator to direct funds to school districts with higher service needs and fewer resources in their communities. Helping parents through the enrollment process initially may contribute to more sustainable funding for school districts that serve more students with limited financial resources at home.[27]

Program enrollments are also indicators of local economic conditions and needs for other services and investment programs beyond education as well.[28]

Multiple Tax Credits and Assistance Programs With Varying Eligibility

The policy response to the pandemic has generated a wide array of changes to assistance programs and tax credits, including both new initiatives and expansions to existing programs. Many of these initiatives are targeted at households with limited resources. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, about 96,000 individuals in New Hampshire lived in poverty, and about one in five households had incomes below $35,000 per year.[29] The pandemic made many more individuals eligible for public assistance, including many who have never accessed public assistance programs before.[30]

Available evidence suggests there has been under enrollment in certain key assistance programs in New Hampshire, including among Granite State children and their families. Lower enrollment in public assistance programs not only reduces their effectiveness at addressing long-term issues such as food insecurity, but also reduces the extent to which these programs beneficially impact the economy.[31]

Many of these programs require applications from eligible individuals before any benefits from these federal appropriations reach Granite Staters. Residents may need additional assistance both applying for benefit programs and filing more complex tax returns than usual to access these available resources. The variety of targeted assistance programs available are administered by many different agencies, have different eligibility thresholds, and require different application processes.

Child Tax Credit

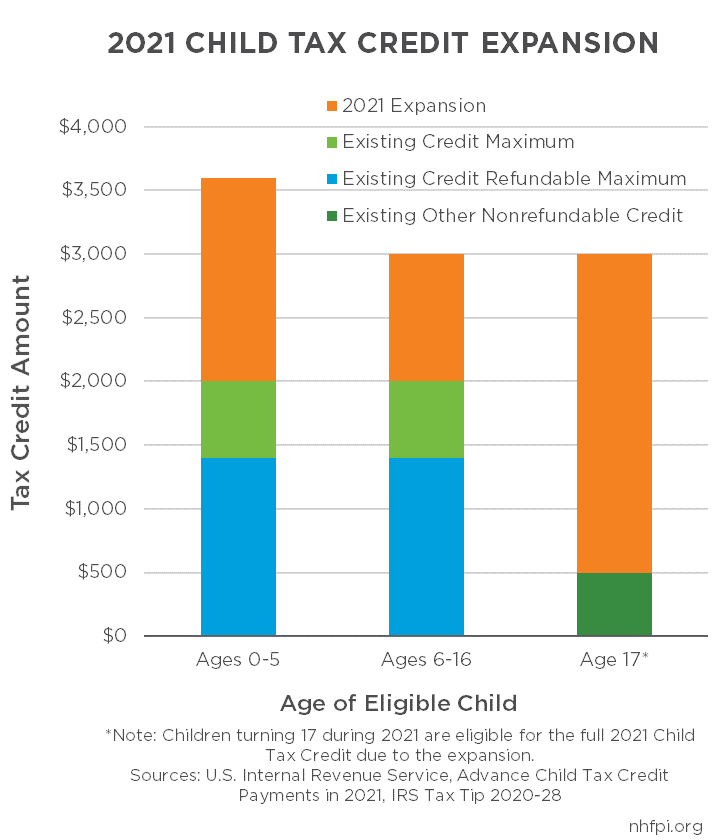

The expanded Child Tax Credit under ARPA boosted the resources available for low- and middle-income families with children both during 2021 and in their tax refunds in early 2022. Relative to 2020, the maximum benefit increased from $2,000 to $3,000 for children ages six to 16 years, from $2,000 to $3,600 for children aged five years and younger, and from $500 (under a separate program) to $3,000 for children aged 17 years, who were previously not covered by the Child Tax Credit.[32] Additionally, the credit was made fully refundable; prior to ARPA, families with little or no tax liability could not receive the full benefit, including families with very low incomes. The expanded credit under ARPA can be received in full by eligible families regardless of income or tax liability.[33]

Even though expanded Child Tax Credit benefits were sent to people that the U.S Internal Revenue Service determined to be eligible on a monthly basis in the second half of 2021 without action, the recipient still needs to claim the Child Tax Credit on their 2021 tax return to access the remaining half of the credit that was not previously distributed on that monthly basis, as well as to avoid the risk of recoupment.[34]

The expanded Child Tax Credit has been estimated by both nonpartisan Congressional staff and independent researchers to reduce child poverty nationally by nearly one half. The Congressional Research Service estimated that the expansion’s benefit would be most significant for families in poverty, with the average Child Tax Credit increasing from $976 to $5,421; increases for higher income households were estimated to be much smaller.[35] Estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Urban Institute suggested that about 8,000 to 11,000 children would be lifted out of poverty in New Hampshire if the expansion were to be made permanent.[36] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities also calculated that approximately 85 percent of New Hampshire children would be in households benefiting from the Child Tax Credit expansion.[37] The U.S. Internal Revenue Service estimated that 7,745 children in New Hampshire were eligible for the Child Tax Credit in 2019 and were not claimed on a tax return for their household.[38]

Moody’s Analytics estimated that each additional dollar of Child Tax Credit paid in the first quarter of 2021 would produce a $1.25 boost in economic output in the fourth quarter of 2021.[39] The Niskanen Center, a nonpartisan think tank, projected the ARPA expansion of the Child Tax Credit would bring $286.8 million to the New Hampshire economy.[40]

Earned Income Tax Credit

Through ARPA, Congress expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to include a wider range of ages and households. For 2021, individuals aged 19 to 24 years or 65 years or older are eligible for EITC (except for students under age 24), whereas prior law only permitted workers aged 25 to 64 years to be eligible. The expanded EITC in 2021 also increases the maximum payment for workers without qualifying dependent children who live with them from $543 to $1,502, with a higher income phaseout.[41]

The expansion of the childless EITC under ARPA will result in roughly $43 million in additional benefits coming to New Hampshire, according to a preliminary, unpublished analysis of data from the Joint Committee on Taxation and the U.S. Census Bureau by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.[42] The expanded EITC would benefit approximately 66,400 working adults in New Hampshire.[43]

As a result of this expansion and similar to the Child Tax Credit, people who previously were not eligible for the EITC may now be eligible, including non-filers. People with very low incomes, including people who are homeless, may not be required to file tax returns; without filing a return, these individuals and families may not access the enhanced credits from the EITC, the Child Tax Credit, or the previously-enacted Economic Impact Payments for which they are eligible.[44] These resources would likely have a profound impact on the well-being of these individuals and families, but they may need assistance in filing complex tax returns or registering properly as a non-filer during the first few months of 2022 to access these benefits.[45]

Nearly one in every five Granite Staters who were eligible for the EITC did not claim it for tax year 2018, suggesting more navigator support and outreach would have been helpful before the pandemic, and would be for the ARPA eligibility expansion as well.[46]

Moody’s Analytics estimated that each additional dollar of Earned Income Tax Credit paid in the first quarter of 2021 would produce a $1.27 boost in economic output nationally in the fourth quarter of 2021.[47]

Enhanced Assistance to Afford Health Insurance

Several temporary changes, in effect for 2021 and 2022, make many more individuals and families eligible for subsidies to buy private health insurance on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s individual marketplaces. Previously, income eligibility for subsidies was capped in absolute terms relative to the poverty level, leaving many middle-income individuals to pay higher premiums. ARPA expanded subsidies to limit the percentage of income that middle-income earners would have to pay for health coverage. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that the number of people eligible for subsidies nationally increased by 20 percent. Additionally, subsidies are enhanced for 2021 and 2022 for lower income levels as well, with premiums eliminated for people with incomes very close to poverty levels.[48]

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated that a New Hampshire couple comprised of two 60-year-olds with a household income of $75,000 would see their premium payments drop by about $985 per month. A family of four, with $120,000 in income, two 40-year-olds, one 10-year-old child, and one five-year-old child would see their monthly premium drop an estimated $291.[49] Separately, the Kaiser Family Foundation calculated that the average decrease in cost for a benchmark plan premium for a 60-year-old in New Hampshire with $55,000 of income would decline by an estimated $317 per month.[50]

Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Extensions

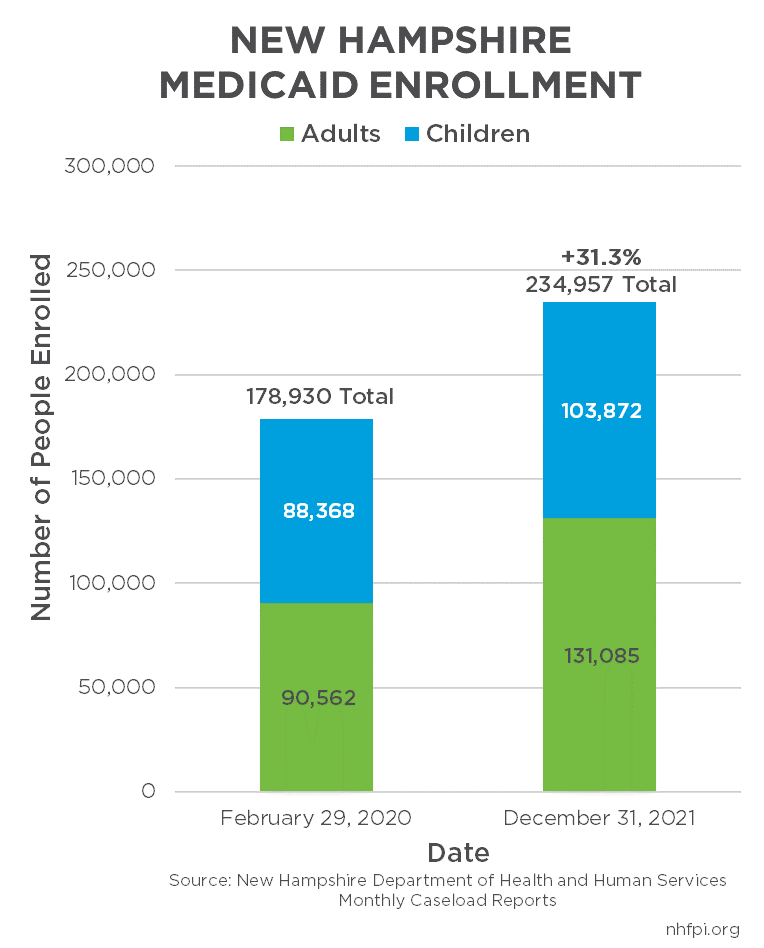

The federal government boosted funding to states for the Medicaid program, which provides health coverage to people with low incomes and limited means.[51] In exchange for the enhanced funding, New Hampshire and other states agreed to not disenroll people from Medicaid during the pandemic. The federal government requires states keep enrollees on Medicaid during the federal Public Health Emergency if they were at any point eligible, and eligibility criteria for the Medicaid program cannot be made more restrictive than it was in January 2020. The enhanced funding will last for the duration of the federal Public Health Emergency as well.[52]

Enrollment in Medicaid grew by 56,027 people (31.3 percent) in New Hampshire between the end of February 2020, just before the pandemic reached the state, and December 31, 2021. This increase included 15,504 children.[53] Many of these individuals may not be eligible for Medicaid after the federal Public Health Emergency ends and the eligibility criteria reverts back to pre-pandemic rules. However, others may need assistance verifying eligibility under pre-pandemic requirements to avoid losing coverage; many individuals may have remained eligible but have not been required to submit recurring paperwork to maintain eligibility that would have been required without the pandemic-induced policy changes. On January 19, 2022, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services reported that more than 86,038 people were at risk of disenrollment when the Public Health Emergency ends due to incomplete, missing, or overdue information, the equivalent of about 37 percent of the Medicaid population.[54] The State has set aside about $2.2 million in funds specifically for additional staffing at the Bureau of Family Assistance’s call center for the end of the Public Health Emergency to help respond to requests for assistance remaining enrolled, but not for more general navigator support.[55]

Additionally, ARPA provided states with an option to expand postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 days after birth to a continuous year, with the federal government making funding available to states for five years.[56] If New Hampshire were to take this option, as pending legislation in the state would require, more mothers of infants would be eligible for Medicaid in New Hampshire, with federal funds supporting health services for them.[57]

Housing and Rental Assistance

Both ARPA and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which passed in December 2020, provided significant aid to states for emergency rental assistance. These appropriations, totaling $352 million to New Hampshire, were substantially similar to each other. These temporary programs were designed to provide rental and utility assistance to households with incomes below 80 percent of the area median income that have a risk of homelessness or housing instability and that have experienced financial hardship or qualified for unemployment compensation due to the pandemic.[58] In New Hampshire, the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority has partnered with the regional Community Action Partnership agencies to handle applications for assistance and distribute the aid.[59] As of January 30, 2022, the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority reported that more than $97.5 million had been expended to help 12,444 New Hampshire households with assistance averaging $7,835 per household, and that funding would be available through at least 2022.[60]

ARPA also established the Homeowner Assistance Fund, which is designed to support those facing difficulty paying their mortgage, utility, or insurance costs due to financial hardship associated with the pandemic.[61] New Hampshire received a $50 million appropriation to assist homeowners in need.[62]

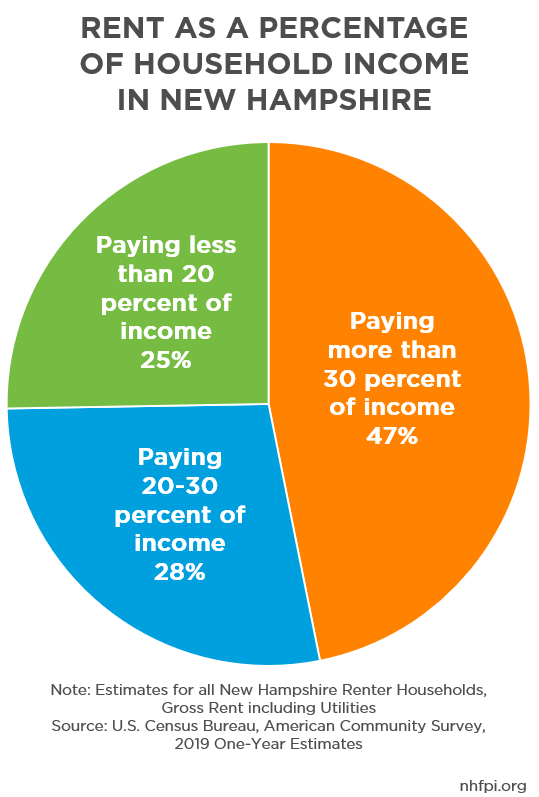

Renter households are more likely to have low incomes than households that own their residence, and may have faced more economic hardships during the pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has disproportionately impacted individuals and families with lower incomes and fewer resources, suggesting renters generally may be in need of assistance.[63] Renter households in New Hampshire had a median income of approximately $45,000 per year in 2019, while people who owned their homes had annual household incomes of about $95,000 in 2019.[64] Prior to the pandemic, nearly half of renter households in New Hampshire were paying 30 percent or more of their incomes in rent.[65] The New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority and regional Community Action Partnership agencies around the state have been working to connect with renters in need; additional navigator support may help get these funds to people sooner and help prevent housing instability, eviction, and financial issues for small-scale landlords, all of which could generate additional, long-term challenges.[66]

Expanded Food Assistance Benefits

Several federal policy changes have resulted in more resources for food assistance benefits since the pandemic began. The federal government recently comprehensively re-evaluated food assistance benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for the first time in 15 years, increasing those benefits by an average of 21 percent starting in late 2021.[67] This increase follows pandemic-related policies that temporarily increased benefits to the maximum levels for all eligible enrollees and, over a more limited time, boosted maximum benefits by 15 percent.[68]

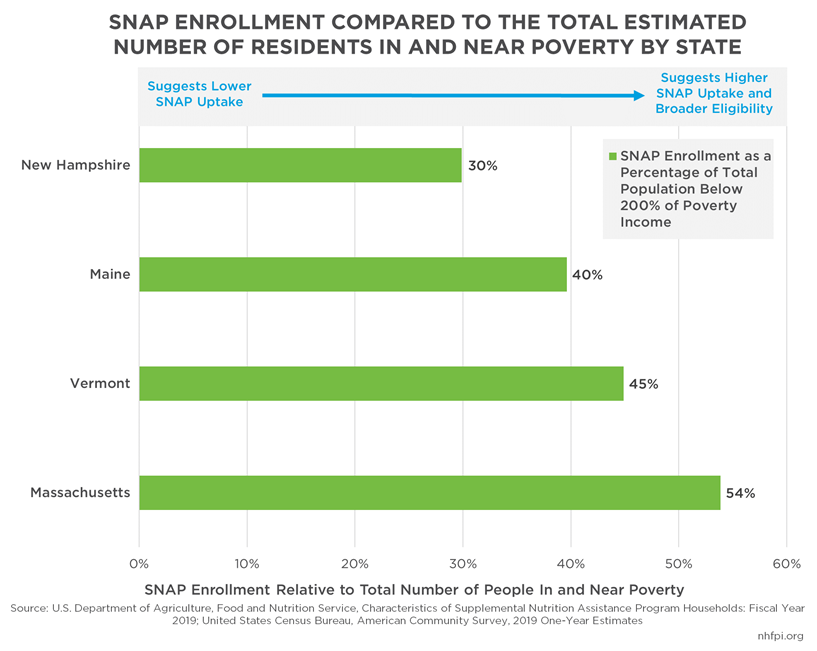

NHFPI analysis conducted in 2021 showed that, in 2019, as many as 17,000 children and thousands more adults were eligible for SNAP benefits, but were not enrolled.[69] Additional NHFPI research identified that outreach plans and broader eligibility policies in neighboring states may have increased SNAP uptake among eligible populations relative to New Hampshire.[70] SNAP enrollment has not increased nearly as substantially during the pandemic as income shocks would suggest, indicating there has likely been higher levels of under enrollment, despite State and nonprofit efforts to conduct outreach.[71] If 17,000 more children in the state had been enrolled in SNAP in 2019, and each child was in a separate household that received the average benefit amount during that year, then an additional $37.9 million in federally-funded aid would have flowed to New Hampshire during 2019, likely providing a significant boost to New Hampshire’s economy and reducing food insecurity.[72]

Moody’s Analytics estimated that each additional dollar of SNAP benefits paid in the first quarter of 2021 would produce a $1.61 increase in economic output in the fourth quarter of 2021, the largest boost among all the added federal expenditures and tax reductions analyzed.[73] Analysis from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows a similar multiplier effect, and also suggests that rural areas see a disproportionately larger benefit from SNAP assistance increases.[74] Earlier analyses indicate SNAP benefits provide positive economic returns on investment during both weak and stronger economies.[75]

Under enrollment in SNAP suggests New Hampshire has an opportunity to provide more support to individuals facing food insecurity as well as to local businesses and rural economies. Once individuals have successfully completed the SNAP applications and enrollment processes for the first time, they may find re-enrolling in these programs less difficult in the future.

Enhanced Nutrition Assistance for Infants, Young Children, and Women

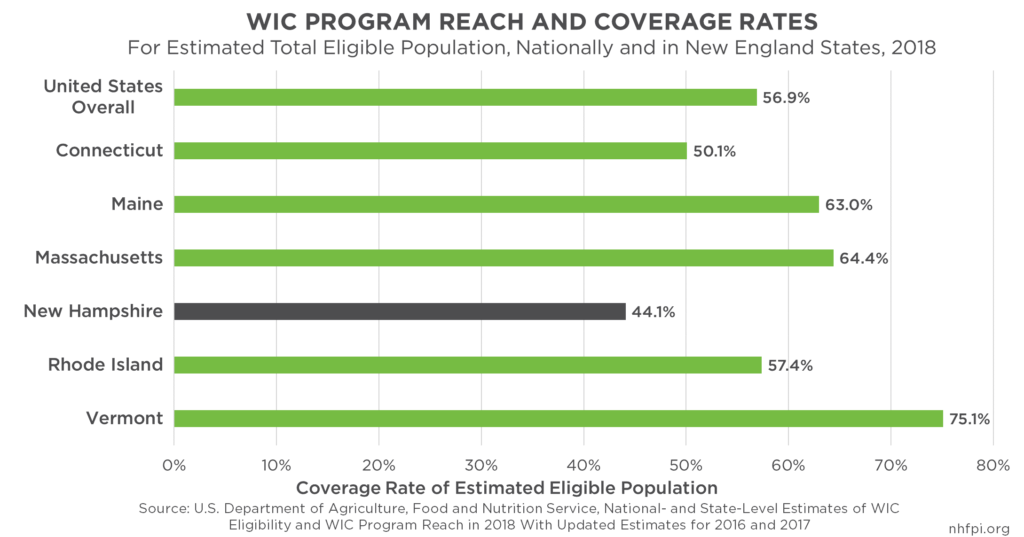

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) serves pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children under the age of five who have low incomes and who face nutritional risks. Eligible enrollees receive redeemable benefits for certain nutritious foods, as well as nutrition education services, referrals to other health or social services, or other supports. Access to the program was enhanced, through federal program waivers, starting in March 2020, and food benefits were expanded to enrollees who previously only received other services through WIC.

NHFPI analysis shows that despite this expansion, overall WIC redemption rates declined, suggesting enrollees may not be aware that they are eligible and receiving these electronically-delivered credits for food assistance. Additionally, WIC was estimated to reach 44.1 percent of the eligible population in New Hampshire in 2018, the lowest of any state except New Mexico, indicating families may need assistance connecting to the program.[76]

Reviews of existing research suggest WIC participation is associated with reduced infant mortality, improvements in birthweight and family diet, and better outcomes for the intellectual development of children.[77] The expanded eligibility for redeemable food benefits through WIC will be available until shortly after the end of the federal Public Health Emergency associated with the pandemic.[78]

Other Benefit Programs

Several other temporary or modified programs are available for eligible Granite Staters. These programs and policies address assistance in key areas of need, including:

- a funding increase and eligibility change to the federal Child Care and Development Block Grants to states, which makes certain essential workers eligible for assistance for child care regardless of income, and additional funding that can be used to support other expansions of eligibility at the state level[79]

- the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer program, which provides food assistance for students who did not receive free or reduced-price meals at school or in a child care setting because of pandemic-induced closures, reduced hours, or limited attendance, and is operational for the duration of the federal Public Health Emergency[80]

- the Low Income Household Water Assistance Program, which was first established by the December 2020 Consolidated Appropriations Act and is a temporary program designed to help people with low incomes pay their water and wastewater bills[81]

- boosted funding for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which more residents may need due to higher heating fuel prices this winter, and Moody’s Analytics estimated generated $1.31 of economic activity at the end of 2021 for every dollar invested early in the year[82]

- the recently-established Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides a discount of up to $30 per month and one-time credits for equipment to eligible households for internet connectivity, and the organization BroadbandNow estimated the enrollment rate for the predecessor program in New Hampshire was the fourth-lowest in the country[83]

Conclusion

New Hampshire has an opportunity to use the substantial, flexible federal resources currently available to promote long-term economic growth and upward mobility for Granite Staters. With significant numbers of New Hampshire residents still struggling to afford usual household expenses, assistance programs established or bolstered by the policy response to the pandemic could provide meaningful assistance to individuals and families at risk of being left behind in the recovery. As of late January 2022, about $579.7 million in flexible federal funds are still unappropriated in New Hampshire, providing State policymakers with the ability and opportunity to make substantial investments in New Hampshire’s people, economy, and future.

The positive impact of these one-time federal funds could be maximized by helping ensure Granite Staters in need access programs to help them care for their families and better participate in the recovery. Public benefit navigators can help educate New Hampshire’s residents about the assistance available to them among the wide array of programs currently operating, and may be particularly helpful for enrolling eligible people for these benefits when programs are changing, newly-expanded, or temporary. Connecting Granite Staters to assistance programs for which they are already eligible can help them put food on the table, stay in their homes, support local businesses, and participate in the economy. Existing programs to help connect eligible people to resources may be insufficient, given the increased needs spurred by the pandemic and prior under enrollment in assistance programs; one-time federal funds could contribute substantially to these efforts and support new, multi-year initiatives.

Public benefit navigators can help contribute to a more equitable economy in the short-term, while also permanently building more human capital and economic prosperity in the years long after flexible federal funding has disappeared. Under enrollment in key assistance programs has potentially left Granite Staters struggling unnecessarily, and limited past economic recoveries. Educating people about these programs can both help them in hard times and bring more federal resources into the New Hampshire economy, returning federal tax dollars to the state in a manner that provides financial support and economic stimulus. A working infrastructure of navigators, with proven results, could also potentially be funded through other means after 2026. Enhancing awareness through publicly-funded navigators can also help build resiliency in historically underserved and disadvantaged communities, mitigating future economic downturns for both these typically disproportionately impacted communities and for the entire state. With significant resources available and rapidly changing public assistance programs, public benefit navigators can help lay the foundation for a future of more inclusive prosperity for all Granite Staters.

Endnotes

[1] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, data collection in Week 41 from December 29, 2021 to January 10, 2022. These results are substantially similar to results from the data collected from the Household Pulse Survey in New Hampshire between December 1, 2021 and December 13, 2021. See also NHFPI’s December 15, 2021 webinar presentation Pandemic Impacts on New Hampshire Families.

[2] For more information, see NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog post Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[3] To see the descriptions of these broad funding areas, see the U.S. Treasury Department’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds web page, accessed January 16, 2022. For more information on funding objectives, see also the U.S. Treasury Department’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Fact Sheet, published May 2021.

[4] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 8.

[5] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 37.

[6] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Final Rule, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77. Funds deployed while the interim final rule is in effect will not be recouped later if they were used in a manner consistent with the interim final rule. For more information, see the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule explainer More Information on the Conclusion of the Public Comment Period and the Interim Final Rule on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. More information regarding the federal government’s initial rule regarding the uses of these funds can be accessed through NHFPI’s May 2021 summary Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[7] For more information, see NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog post Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments and NHFPI’s September 1, 2021 blog post Nearly 20 Percent of State’s New Flexible Federal Funds Have Been Appropriated. See also the U.S. Treasury Department’s Final Rule, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77.

[8] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 37.

[9] For the expansion on the interim final rule, see the U.S. Treasury Department’s Final Rule, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, pages 92-93.

[10] See NHFPI’s November 17, 2021 post More Than One Third of the State’s Flexible Federal Funds for COVID-19 Recovery Appropriated.

[11] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 20 and the Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 93, 26791, May 17, 2021.

[12] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 20.

[13] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, page 18.

[14] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Interim Final Rule for the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, pages 19 and 30.

[15] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Final Rule, 31 CFR Part 35, RIN 1505-AC77, pages 92-93.

[16] For more information on the pandemic’s economic impacts in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s September 1, 2021 Issue Brief Uneven Employment Impacts and Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s April 9, 2021 blog post The COVID-19 Crisis After One Year: Economic Impacts and Challenges Facing Granite Staters, NHFPI’s September 23, 2020 Issue Brief New and Expanded Challenges Facing Vulnerable Populations in New Hampshire, NHFPI’s April 14, 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses, NHFPI’s January 20, 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s Economy, Household Finances, and State Revenues, NHFPI’s December 15, 2021 presentation Pandemic Impacts on New Hampshire Families, and NHFPI’s March 19, 2021 webinar Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis. For more information on the expansion of program eligibility and benefits, see NHFPI’s November 16, 2021 blog post Federal Funds Boost Home Heating Assistance Ahead of Expected Winter Price Increases, NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas, NHFPI’s May 28, 2021 blog post Unemployment Insurance and the Continued Economic Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services, NHFPI’s December 29, 2020 blog post New Federal Law Sends More Aid to Unemployed, Low-Income Granite Staters, NHFPI’s June 18, 2020 blog post CARES Act Economic Impact Payments May Not Automatically Reach 9,900 Eligible Granite Staters, and NHFPI’s March 27, 2020 blog post Federal CARES Act to Provide Relief to Residents, $1.25 Billion to New Hampshire State Government.

[17] For examples, see NHFPI’s December 16, 2021 Issue Brief The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children: Enrollment Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s October 25, 2019 blog post Pending Federal Proposals Would Reduce SNAP Benefits, Including Enrollment of Households with Children, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ September 29, 2016 report SNAP Works for America’s Children. See also the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Research on Poverty’s June 2019 Fast Focus The Brain Science of Poverty and Its Policy Implications.

[18] For more information and discussion, see NHFPI’s August 25, 2021 Issue Brief Greater Investments Key for Students Facing Inequities Across New Hampshire, NHFPI’s January 14, 2021 Fact Sheet Resource Inequities by Population Group, and NHFPI’s June 30, 2020 Issue Brief Inequities Between New Hampshire Racial and Ethnic Groups Impact Opportunities to Thrive.

[19] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities May 7, 2021 Issue Brief Priorities for Spending the American Rescue Plan’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds.

[20] For more detail on the timelines for appropriating and using the CSFRF, see NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog post Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[21] For example, the New Hampshire Emergency Rental Assistance Program is administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority in partnership with New Hampshire’s five Community Action Partnership agencies, while the Homeowners Assistance Fund is administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority itself. Granite United Way administers the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program. The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services also conducts certain outreach related to SNAP and WIC. The NH Navigators program helps residents enroll in health coverage through the Affordable Care Act. The NH Works System helps connect residents to education and training resources. City and town welfare offices may also help connect individuals to resources and services for which they are eligible.

[22] The program approved by the New Hampshire Executive Council is described in a September 13, 2021 letter from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Economic and Housing Stability, approved at the October 13, 2021 Executive Council meeting.

[23] For more information and citations, see NHFPI’s February 8, 2021 Issue Brief Designing a State Budget to Meet New Hampshire’s Needs During and After the COVID-19 Crisis. For specific Congressional Budget Office analyses, see The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output, September 2020, and Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in 2012 and 2013, November 15, 2011.

[24] See the Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon.

[25] For prior assessments from Moody’s Analytics, see Blinder and Zandi How the Great Recession Was Brought to an End, July 27, 2010, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities October 15, 2015 publication by Blinder and Zandi, The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

[26] For more information on the American Rescue Plan Act, see NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services.

[27] For more information on free and reduced-price school meal enrollment as an indicator of local poverty, see NHFPI’s August 17, 2021 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023, NHFPI’s November 4, 2021 presentation Measuring Student Hardship by Municipality: Free and Reduced-Price School Meal Eligibility and Other Metrics for Understanding Local Poverty and Income, NHFPI’s April 9, 2021 presentation Education Funding in New Hampshire: A Brief Overview, and NHFPI’s May 6, 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[28] For example, the New Hampshire Community Development Finance Authority uses Community Progress Indicators, which were developed with assistance from NHFPI, to help guide funding and investment decisions. Inputs for these Community Progress Indicators include SNAP enrollment and free and reduced-price school meal eligibility for each community.

[29] See NHFPI’s September 18, 2020 Fact Sheet Census Bureau 2019 Estimates for Income, Poverty, Housing Costs, and Health Coverage.

[30] See NHFPI’s Issue Briefs from September 1, 2021, Uneven Employment Impacts and Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, and September 4, 2020, Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[31] For more information of the impact of public policy on food insecurity, see NHFPI’s October 1, 2021 blog post Recent Data Show Food Insecurity Increases Mitigated by Expanded Aid During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[32] For comparisons to prior tax law, see the U.S. Internal Revenue Service Publication 972, Child Tax Credit and Credit for Other Dependents, for 2020 Returns, published January 11, 2021.

[33] To learn more about the Child Tax Credit expansion, see the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Looking Ahead: How the American Rescue Plan Affects 2021 Taxes, Part 2 (COVID Tax Tip 2021-79), June 3, 2021. See also NHFPI’s May 19, 2021 webinar presentation Federal Aid and the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services, the Congressional Research Service’s May 12, 2021 report The Child Tax Credit: Temporary Expansion for 2021 Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117-2), and the Congressional Research Service’s July 12, 2021 report The Child Tax Credit: The Impact of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA; P.L. 117-2) Expansion on Income and Poverty.

[34] For additional information on the structure of the Child Tax Credit, see the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s web pages Advance Child Tax Credit Payments in 2021 and 2021 Child Tax Credit and Advance Child Tax Credit Payments Frequently Asked Questions.

[35] For the full research findings, see the Congressional Research Service’s July 12, 2021 report The Child Tax Credit: The Impact of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA; P.L. 117-2) Expansion on Income and Poverty.

[36] For the Urban Institute analysis estimating 11,000 children would be lifted out of poverty in New Hampshire by extending the current Child Tax Credit expansion, see the August 2021 report Expanding the Child Tax Credit Could Lift Millions of Children Out of Poverty. For the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimate of 8,000 New Hampshire children being lifted out of poverty by an extended expansion of the Child Tax Credit, see the May 24, 2021 report Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent.

[37] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities May 24, 2021 report Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent.

[38] For the full dataset, including analysis by ZIP code, see the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s web page 2021 Child Tax Credit and Advance Child Tax Credit Payments: Resources and Guidance.

[39] See the Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon.

[40] See The Niskanen Center’s August 2, 2021 report Measuring the Child Tax Credit’s Economic and Community Impact. See also The Niskanen Center’s About web page.

[41] For more information, see the Congressional Research Service’s May 3, 2021 report The “Childless” EITC: Temporary Expansion for 2021 Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117-2). See also the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities March 12, 2021 report American Rescue Plan Act Includes Critical Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC.

[42] Estimate provided by email to NHFPI by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[43] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities May 24, 2021 report Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent.

[44] For more information on Economic Impact Payments, see NHFPI’s June 18, 2020 blog post CARES Act Economic Impact Payments May Not Automatically Reach 9,900 Eligible Granite Staters.

[45] For more information, see the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s web pages Experiencing Homelessness? You Can Still Receive Advance Child Tax Credit Payments, Third Economic Impact Payment, How to Get Advance Child Tax Credit Payments if You Don’t Have a Bank Account, Child Tax Credit Non-Filer Sign-Up Tool, and How to Claim the Earned Income Tax Credit.

[46] See the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s web page EITC Participation Rate by States Tax Years 2011 through 2018.

[47] See the Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon.

[48] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s March 15, 2021 Data Note Impact of Key Provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 COVID-19 Relief on Marketplace Premiums.

[49] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities March 11, 2021 report Health Provisions in American Rescue Plan Act Improve Access to Health Coverage During COVID Crisis.

[50] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s March 15, 2021 report Impact of Key Provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 COVID-19 Relief on Marketplace Premiums.

[51] For more information on Medicaid in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s July 25, 2017 blog post Medicaid Assists More Than 185,000 New Hampshire Residents and NHFPI’s March 30, 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes. See also the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid.

[52] For more information, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and the University of New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice July 29, 2021 presentation DHHS Preparation for End of Federal Public Health Emergency Impact on Medicaid and Other Benefits.

[53] Data from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Monthly Caseload Reports. Learn more about monthly Medicaid enrollment in New Hampshire on the Department’s Medicaid Enrollment Data website.

[54] Data based on data provided in the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and University of New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice January 19, 2022 presentation Medicaid Continuous Coverage During the Pandemic. See also the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and the University of New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice July 29, 2021 presentation DHHS Preparation for End of Federal Public Health Emergency Impact on Medicaid and Other Benefits.

[55] For information regarding this appropriation, see Fiscal Item FIS 21-169, June 14, 2021.

[56] For more information, see the Kaiser Family Foundation’s December 16, 2021 publication Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker. See also The Commonwealth Fund’s August 11, 2021 post State Options for Extending Medicaid Postpartum Coverage and The Pew Charitable Trusts May 5, 2021 Stateline article States Push to Extend Postpartum Medicaid Benefits to Save Lives.

[57] See House Bill 1536 and Senate Bill 407, both of the 2022 Legislative Session.

[58] For more information, see NHFPI’s December 29, 2020 blog post New Federal Law Sends More Aid to Unemployed, Low-Income Granite Staters, NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services, the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s web page The NH Emergency Rental Assistance Program, the New Hampshire Emergency Rental Assistance Program Frequently Asked Questions for Renters/Tenants About NHERAP document, the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s tracking document Federal COVID-19 Funds – New Hampshire Allocations as of December 28, 2021, and the U.S. Treasury Department’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program web page.

[59] See the HomeHelpNH web page about the New Hampshire Emergency Rental Assistance Program.

[60] Periodically updated data are available on the New Hampshire House Finance Authority website for the New Hampshire Emergency Rental Assistance program. See also the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority November 1, 2021 web posting Emergency Rental Assistance for Rent and Utilities is Available.

[61] See the U.S. Treasury Department’s Homeowner Assistance Fund web page, as well as NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services.

[62] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s tracking document Federal COVID-19 Funds – New Hampshire Allocations as of December 28, 2021.

[63] See NHFPI’s September 1, 2021 Issue Brief Uneven Employment Impacts and Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s September 23, 2020 Issue Brief New and Expanded Challenges Facing Vulnerable Populations in New Hampshire, NHFPI’s April 14, 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses, NHFPI’s January 20, 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s Economy, Household Finances, and State Revenues, NHFPI’s December 15, 2021 presentation Pandemic Impacts on New Hampshire Families, and NHFPI’s March 19, 2021 webinar Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis.

[64] See the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey median household incomes of renters and homeowners in New Hampshire in 2019.

[65] See NHFPI’s June 8, 2021 Data Byte Nearly Half of Renter Households in New Hampshire Cost-Burdened Before Pandemic.

[66] For more research on the long-term benefits of housing assistance and reduced housing instability, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities December 5, 2019 report Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families.

[67] See NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas.

[68] See NHFPI’s April 3, 2020 blog post New Hampshire Expands Access to Safety Net Programs and Supports During the COVID-19 Crisis, NHFPI’s December 29, 2020 blog post New Federal Law Sends More Aid to Unemployed, Low-Income Granite Staters, NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog post Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services, and NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas.

[69] See NHFPI’s July 15, 2021 Issue Brief The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: An Overview of Potential Under Enrollment in New Hampshire.

[70] See NHFPI’s October 7, 2021 Issue Brief The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: State Outreach to Eligible Populations.

[71] See NHFPI’s July 15, 2021 Issue Brief The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: An Overview of Potential Under Enrollment in New Hampshire.

[72] For more information, see NHFPI’s July 15, 2021 Issue Brief The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: An Overview of Potential Under Enrollment in New Hampshire, NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas, Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities October 15, 2015 publication by Blinder and Zandi, The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

[73] See the Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon.

[74] See NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas.

[75] See NHFPI’s July 15, 2021 Issue Brief The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: An Overview of Potential Under Enrollment in New Hampshire, NHFPI’s November 9, 2021 blog post Federal Increases to SNAP Benefits May Aid the Recovery from the COVID-19 Crisis More in Rural Areas, Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities October 15, 2015 publication by Blinder and Zandi, The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

[76] For more information on WIC enrollment and eligibility in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s December 16, 2021 Issue Brief The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children: Enrollment Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[77] For more information and research on WIC, see NHFPI’s December 16, 2021 Issue Brief The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children: Enrollment Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[78] See the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service September 21, 2020 WIC Policy Memorandum #2020-6 Extension for Certain Approved COVID-19 Waivers.

[79] See the Bipartisan Policy Center’s March 24, 2021 post Child Care in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and the Federal Reserve System’s Community and Economic Development, Early Care and Education Work Group July 16, 2021 report Considerations in Deploying ARPA Funds for Childcare.

[80] See the United States Department of Agriculture Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer Program (P-EBT) Approval of New Hampshire’s State Plan for Summer 2021 from October 21, 2021.

[81] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Low Income Household Water Assistance Program web page, the U.S. Administration for Children and Families presentation Low Income Household Water Assistance Program Information and Feedback Session, Tuesday, April 20, 2021, and the National Association of Counties June 7, 2021 post HHS launches new Low-Income Household Water Assistance Program (LIHWAP).

[82] See NHFPI’s November 16, 2021 blog post Federal Funds Boost Home Heating Assistance Ahead of Expected Winter Price Increases and Moody’s Analytics January 15, 2021 publication The Biden Fiscal Rescue Package: Light on the Horizon.

[83] For more information on the Affordable Connectivity Program, see the U.S. Federal Communications Commission web page on the program. For the BroadbandNow state-by-state analysis of uptake in the Emergency Broadband Benefit program, the predecessor to the Affordable Connectivity Program, see the BroadbandNow analysis Emergency Broadband Benefit Recap: 7.1 Million Households Enrolled, Adoption Varies Significantly by State, published December 6, 2021.