The COVID-19 crisis has had widespread impacts on life in New Hampshire, but the negative effects have been most severe on people who were already the most vulnerable. Certain groups of Granite Staters have historically experienced disproportionate health and economic challenges. Vulnerable groups in New Hampshire include older adults, people with disabilities, individuals with chronic health conditions, individuals and families with lower incomes and who are economically disadvantaged, and people identifying as a race or ethnicity other than white and non-Hispanic. These groups encompass individuals and families with fewer resources available as well as those requiring additional care or support for their wellbeing. State Budget investments to provide support and aid to these Granite Staters helped address some key needs prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis; however, this crisis has further exacerbated the challenges faced by families, children, and individuals throughout New Hampshire and within these vulnerable groups.

The COVID-19 crisis has necessitated limits on physical interactions to reduce the spread of the virus. These measures have also led to interruptions in healthcare services, changes to education and work situations, significant effects on certain industries, historically high levels of unemployment, and a severe economic recession. Those unable to limit certain physical interactions due to their employment or living circumstances face heightened risks to their health or wellbeing.

The risks presented by this crisis, and the resulting effects on health, finances, and economic security have been severe for many Granite Staters. Additionally, the impacts on the State’s revenue streams may affect the ability to sustain continued and additional investments vital to support the wellbeing of vulnerable Granite Staters throughout this crisis and the subsequent recovery. While there have been key policy actions at both the state and federal level in response, the uncertainty surrounding the duration and severity of the impacts of this crisis may necessitate additional investments and policies. These investments would likely be most effective when targeted toward supporting those who have been historically vulnerable in New Hampshire and have experienced heightened challenges due to the crisis. Additional resources might also be focused on supporting those who are now facing new challenges and are directly impacted by, or are vulnerable to, serious health complications and economic hardships due to the COVID-19 crisis.

This Issue Brief explores the challenges certain groups of Granite Staters experience and how those vulnerabilities have been exacerbated as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. This Issue Brief outlines key policies and investments relevant to supporting these vulnerable populations in New Hampshire that had been implemented prior to the COVID-19 crisis, and the importance of key programs supported through state and federal funds administered by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. This Issue Brief also identifies the potential need for future policy changes and investments that may aid in supporting these populations throughout this crisis and the subsequent recovery period.

Vulnerable Groups in New Hampshire

Several groups in New Hampshire have faced challenges that disproportionately jeopardize their health and economic wellbeing, and which have made them particularly susceptible to the negative effects of the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated key health and economic challenges and emphasized the needs for additional care and supports.[i]

Older Adults and Individuals in Need of Long-Term Care and Support

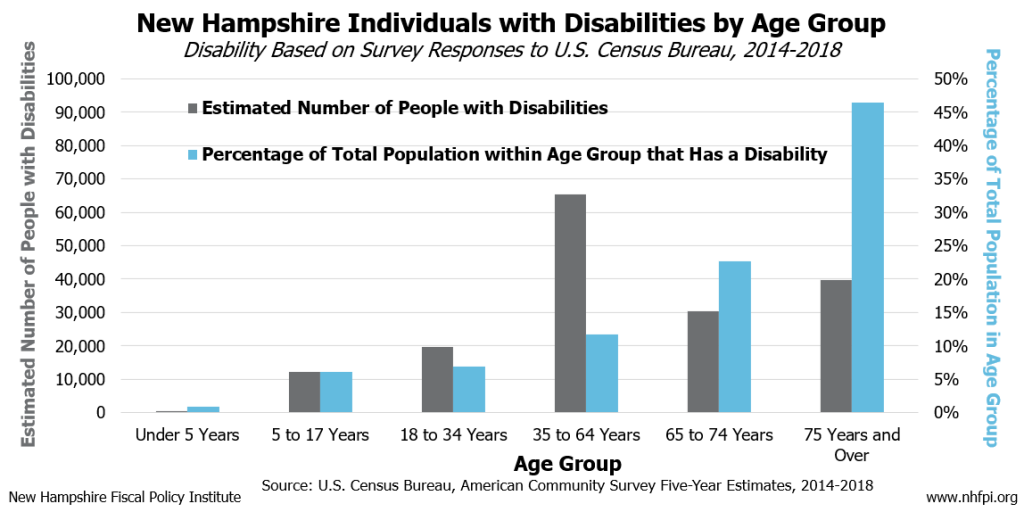

New Hampshire has a relatively high median age, which has been increasing over time. The median age in the state was estimated at 43.1 years old in 2019.[ii] From 2010 to 2019, the population under age 65 declined by about 32,000 people, while the population aged 65 and older grew by 74,000. Estimates for 2019 show that Granite Staters over the age of 65 totaled approximately 254,000 individuals, or about 18.6 percent of the overall population, compared to about 13.6 percent of the population in 2010.[iii] This growing subset of the population may be more likely to require long-term care, especially for a disability, as the estimated prevalence of disability increases with age.

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, funding availability for key Medicaid programs such as long-term care programs, along with workforce constraints for Medicaid providers in New Hampshire, may have limited health care services for certain Granite Staters. Long-term care programs for adults and children with limited means who are chronically ill, experiencing disability, or require developmental support may be provided by New Hampshire’s Medicaid program. Specifically, certain programs within Medicaid allow for direct care for those eligible within their own homes or communities through visitation.

One such program is the Choices for Independence (CFI) program, which supports older adults and those with disabilities who have a chronic illness or disability or who are clinically in need of care at the level provided in a nursing home. This program allows for individuals to receive care in their own homes and communities. NHFPI analysis from early 2019 concluded that Medicaid reimbursement rates in New Hampshire for CFI services had not kept up with inflation in recent years, which may have contributed to worker shortages and unfulfilled services for those receiving care through this program. These challenges may have left individuals requiring long-term care in New Hampshire without services, or unable to receive needed services in a timely manner.[iv]

Individuals Requiring Mental Health Care or Substance Use Disorder Treatment

One in five Americans reported having a form of mental illness from 2017-2018. Over this period about 17 million adults and 3 million adolescents nationally reported major depressive episodes, and about 4.3 percent of the population reported having serious suicidal ideations, while in 2018, additional data show nearly a third of adults reported feeling anxious or worried on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis.[v] In New Hampshire, access to mental health care for children and adults has been limited in the past, and additional investments to enhance access to care were enacted in recent legislation. Restricted availability for critical intervention, emergency care, and rehabilitation services previously created waitlists for mental health care for children and adults. State legislation in 2017 emphasized that mental health care needs were not being met given the capacity of mental health services at the time, and required the development of a 10-Year Mental Health Plan by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, along with a task force to study the challenges in New Hampshire.[vi]

In addition to challenges for those requiring mental health services, the substance use disorder crisis in New Hampshire, fueled by the opioid crisis, has been difficult to mitigate due to a lack of rehabilitative treatment infrastructure. Similar to trends throughout the nation, the significant increase in opioid-related overdose deaths began in 2014. From 2012 to 2018, over 1,900 Granite Staters lost their lives due to opioid overdoses. Additional investments made into substance use disorder treatment have recently been appropriated, yet the need for services remains elevated. The ability to provide care for individuals impacted by substance use disorders had been hindered by a lack of sufficient recovery infrastructure throughout the state in the past, placing pressure on hospital emergency departments for certain care requiring rapid intervention.[vii]

Families and Individuals with Limited Economic Security

Before the COVID-19 crisis, lower- and middle-income Granite Staters had only recently seen their inflation-adjusted wages return to the levels experienced prior to the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, while wages for higher income earners had been impacted less negatively and recovered more rapidly. This delayed recovery in the purchasing power of lower- and middle-income Granite Staters occurred alongside a critical labor market shift. Throughout the last economic recovery, which ended at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, shifts in employment occurred relative to before the Great Recession. Increases in employment in large industries that paid lower-than-average wages, along with decreases in employment in certain key industries that paid higher-than-average wages, took place. The challenges of lower than average wages being paid to many workers in New Hampshire was combined with several other financial burdens. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, individuals and families faced elevated expenses, especially related to housing affordability and stability, depending on their resource levels. The most severe economic challenges were faced by those with very low incomes, and those living in poverty.[viii]

Food Insecurity and Poverty

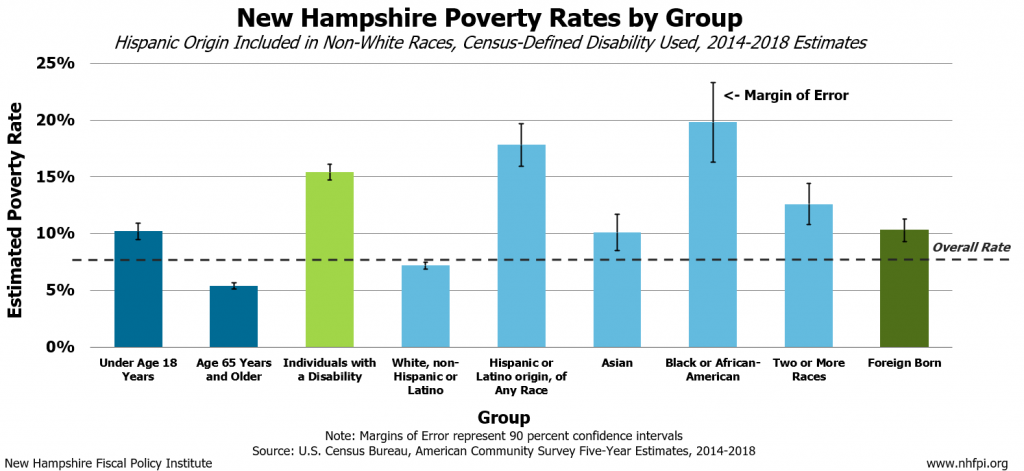

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, about 7.3 percent of residents in New Hampshire lived in poverty, based on data for 2019.[ix] These Granite Staters had incomes below the federal poverty thresholds. In 2019, these federal thresholds were $13,300 for a household with one adult under age 65 and no children, and $25,926 per year in income for a household with two adults and two children.[x] About 96,000 Granite Staters were estimated to live below these poverty thresholds before the COVID-19 crisis began.[xi] Poverty rates were different among Granite Staters as well; women, children, and individuals identifying as non-white and not Hispanic or Latino faced elevated levels of poverty. Poverty rates by family compositions were also quite different; for example, the poverty rate among households headed by a single female with a dependent child under the age of five was estimated at 35.4 percent before the crisis.[xii]

Many families and individuals navigating poverty also faced food insecurity, meaning that at times these households were unable to acquire adequate food because they had insufficient resources to purchase food. In New Hampshire, 6.6 percent of households were estimated to be food insecure during the 2017-2019 period. This represents about 35,500 households where food insecurity occurred at least once during the year prior to reporting.[xiii] Those Granite Staters experiencing poverty or food insecurity may be exposed to detrimental and long-term health impacts, and developmental and behavioral challenges among children.[xiv]

Housing Affordability Challenges

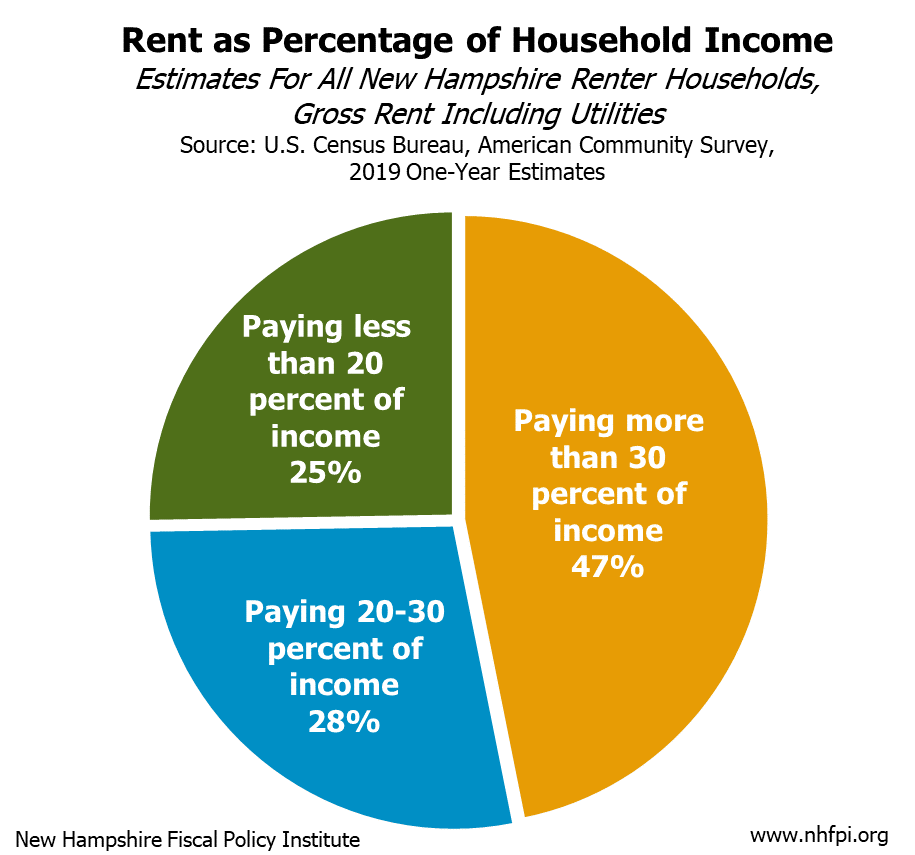

Housing affordability and stability has become a growing challenge for Granite Staters with lower- or more modest incomes. Those with lower incomes are more likely to live in rental housing; the median household income of renters in the state was estimated to be about $45,000 per year in 2019, which was only slightly more than half the median household income of homeowners.[xv] In 2019, the median rental costs for a two-bedroom apartment in the state was estimated at $1,347, and the median home price crested $300,000.[xvi] Individuals who are renters are particularly sensitive to income loss, mainly due to these high housing costs. In 2019, estimates show that about 47 percent of renters in New Hampshire were spending more than 30 percent of their incomes on rental costs. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development states that, “families who pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing are considered cost burdened and may have difficulty affording necessities such as food, clothing, transportation and medical care.” Nearly half of the renters in the state were considered cost burdened by this definition even before the current crisis began. Rising rental and purchase costs for housing may have strained the budgets of many Granite Staters and limited the resources they could use for food, health care, or saving for the future prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, and has impacted the housing stability of many Granite Staters.[xvii]

Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups

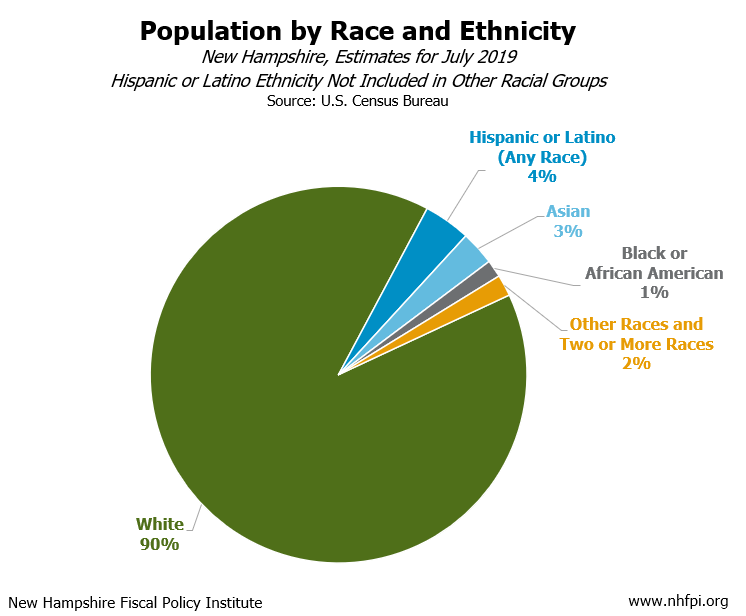

The growing subset of the population in New Hampshire identifying as something other than white and non-Hispanic have faced intersectional challenges that place additional risks on their wellbeing. In 2019, just under 90 percent of Granite Staters identified as non-Hispanic white, compared to just over 92 percent estimated in 2010, indicating the state has become more diverse over the past decade.[xviii] In New Hampshire, poverty was estimated to be more prevalent among certain racial and ethnic groups than others. In the five years from 2014 to 2018, about one in every five New Hampshire residents identifying as Black or African American were in poverty, as well as about one in six identifying as Hispanic or Latino. One in every ten Granite Staters identifying as Asian and one in eight identifying as two or more races were in poverty. For the overall New Hampshire population, about one in 13 individuals experienced poverty during this period. Higher rates of poverty among these groups is indicative of uneven access to employment opportunities, which may contribute to decreased access to health care, education, and stable housing.[xix]

Key Investments to Support Vulnerable Groups Prior to the COVID-19 Crisis

The State Fiscal Years 2020-2021 New Hampshire State Budget, along with additional state-level programs and initiatives, made several key investments to begin addressing some of the challenges faced by many groups of Granite Staters. Appropriations and aid that were key to assisting vulnerable Granite Staters before the COVID-19 crisis include increased investments for programs within Medicaid, greater access to mental health care and substance use disorder treatment, and additional funding for housing support programs to assist those with who were homeless or at risk of homelessness.

Medicaid Healthcare Services

The current State Budget made a key investment related to reimbursements rates for Medicaid programs, appropriating an additional $31 million for a rate increase for nearly all services, including within long-term care, to be matched by federal funds. Services not included in the reimbursement rate increase from that appropriation were supported through a separate rate increase.[xx] Despite these recent investments, care provided in congregate settings like long-term care facilities, and care provided to individuals in their homes, is more difficult due to the COVID-19 crisis. Older adults and those with chronic health conditions have been shown to be more susceptible to serious illness and negative health outcomes resulting from COVID-19.

The challenge of providing care to vulnerable populations during this crisis stems from the risk of viral spread. Mitigating physical interaction may be extremely difficult among individuals who require direct care for chronic illnesses, disabilities, or developmental services. Certain services for those individuals may be delayed or altered during the crisis due to health concerns and workforce availability.[xxi]

Mental Health Care and Substance Use Disorder Services

Appropriations made in the current State Budget took steps to address the need for more infrastructure to increase access to mental health care and substance use disorder treatment. Substance use disorder services were appropriated $12 million in federal funds, and $1 million in State funds was appropriated for treatment and housing facilities. Another $450,000 was appropriated for shelter and stabilization services. Following several recommendations outlined in the 2018 Ten Year Mental Health Plan, mental health services received appropriations in the form of $8.75 million for a new secure psychiatric hospital, $5 million for a separate facility for children, $4 million to expand New Hampshire Hospital adult capacity, $5 million for 40 transitional housing beds, and the establishment of statewide mobile crisis unit response coverage for children.[xxii]

These actions were critical steps to provide much needed additional care and support to Granite Staters. However, mental health and substance use disorder challenges created and exacerbated during the COVID-19 crisis will require continued and likely increased investments as additional care or treatment services may be required during the COVID-19 crisis and in subsequent years.

Housing Affordability and Stability

The current State Budget also made several investments and policy changes in order to improve housing affordability, reduce homelessness, and promote new affordable home construction. An annual $5 million contribution to the Affordable Housing Fund was included in the State Budget. In addition, $2 million was appropriated for eviction prevention assistance through the provision of short- and medium-term rental assistance, along with $1 million in rapid re-housing programs to prevent homelessness, improve affordable housing, and increase transitional housing by collaborating with local organizations. The State Budget also included a $1 million appropriation for homeless shelter case management to connect clients to other supports, such as medical and mental health care and social service programs, and $400,000 was appropriated for outreach efforts to homeless youth.[xxiii]

While these appropriations were designed to help address the housing affordability and stability challenges that existed before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, they may not be sufficient to address needs during the COVID-19 crisis. Many renters were already cost burdened by housing before the pandemic began, and with lower income groups disproportionately impacted by the economic effects of the crisis, more individuals and families may struggle to afford housing.[xxiv]

New and Exacerbated Challenges Due to the COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 crisis has progressed quickly in New Hampshire. The immediate health implications and subsequent economic effects have been particularly concentrated among certain groups. While everyone is susceptible to contracting the 2019 novel coronavirus, some populations of Granite Staters face a higher likelihood of coming into contact with the virus, are at a heightened risk of more serious negative health outcomes of the virus, or are more susceptible to the negative economic impacts related to the pandemic. The negative health effects may be mitigated by limiting certain activities, yet not everyone is able to effectively practice social distancing due to their circumstances. Distancing may be particularly difficult among certain groups, especially those who require regular direct health care, have underlying health conditions, are members of historically marginalized groups, have limited incomes or resources, or work in a job that interacts with the public and where remote work is not possible. Many Granite Staters most at risk of the negative health and economic implications of the COVID-19 crisis were already facing disproportionate challenges due to resource limitations.

Health Challenges

Older Adults

Older adults have been shown to be more susceptible to serious illness and negative health outcomes resulting from COVID-19. Specifically, populations over the age of 65, including those living in congregate settings such as nursing homes and assisted living facilities, are at higher risk than the overall population. This growing population of older Granite Staters may be at greater risk for negative health outcomes of COVID-19 and require greater levels of care now and in the future. Populations over the age of 65, and those living in congregate settings such as nursing homes and assisted living facilities, are at higher risk than the population as a whole. Analysis from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that most deaths caused by COVID-19 have been among individuals over the age of 65.[xxv] Those with chronic health conditions, such as severe obesity, serious heart disease, asthma, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, or who are immunocompromised are also at elevated risk of serious negative health effects of the 2019 novel coronavirus.[xxvi]

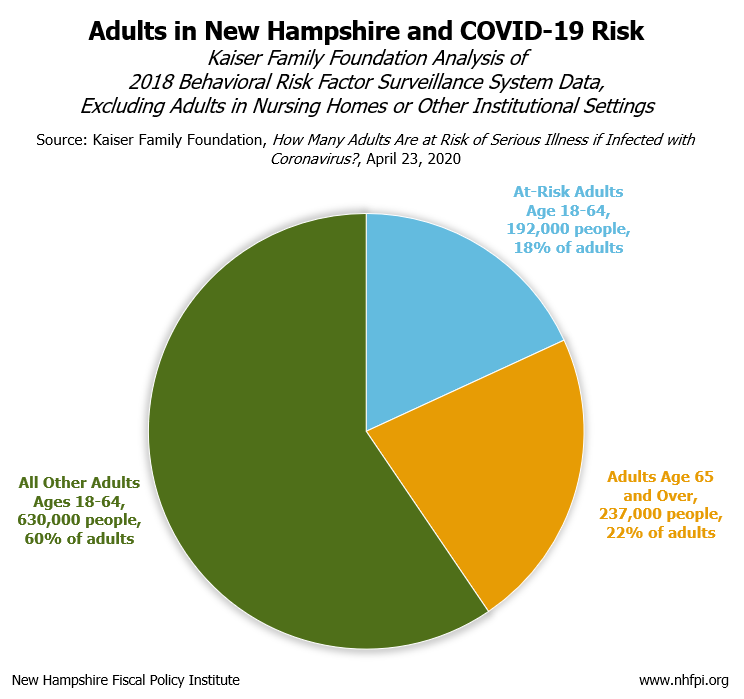

Individuals with Chronic Health Conditions or Disabilities

Survey data from 2018 suggest that many Granite Staters under age 65 were living with chronic health conditions before the COVID-19 crisis began. These health conditions include cancer, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or diabetes, and result in individuals being at risk of more serious health outcomes if they were to contract the 2019 novel coronavirus. Of New Hampshire adults under 65 years old, about 23 percent, or 192,000, of them were considered at a higher risk of more serious health effects of COVID-19 due to their underlying conditions. Another condition increasing the risk of serious negative health impacts of COVID-19 is asthma. Asthma is prevalent throughout the state, with disparities present based on income and ethnic and racial group.[xxvii]

Individuals with disabilities may also be more susceptible to contracting the 2019 novel coronavirus and be more vulnerable to the health impacts of COVID-19 for several reasons. Individuals with disabilities who receive care or support in congregate settings or require individual care from direct care staff may be at greater risk of exposure. Individuals with disabilities who have any underlying health conditions are at heightened risk for negative health effects, due to these factors. They may also have certain services delayed due to the pandemic for a variety of reasons, such as direct care workforce shortages or a lack of transportation.[xxviii] Estimates for 2019 show that about 13.1 percent of the overall population in New Hampshire was identified as having a disability, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.[xxix]

Individuals Requiring Mental Health Care and Substance Use Disorder Treatment

The COVID-19 crisis may exacerbate the need for more mental health care supports due to the uncertainty surrounding the crisis and effects of social isolation. Individuals who are older or who have chronic health conditions may be the most likely to experience social isolation; however, all individuals and children minimizing physical interactions with others are at risk of feeling isolated. Loneliness and feelings of isolation have significant psychological impacts, and are a major risk factor for suicidal ideation, especially among adolescents. Polling conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation throughout the COVID-19 crisis found that a majority of individuals practicing social and physical distancing and sheltering-in-place have reported negative mental health effects due to worry or stress, with about a quarter of those reporting their negative mental health effects were major.[xxx]

Uncertainty surrounding job and financial security present many challenges for the mental well-being of individuals. Over half of individuals who have lost their job or income due to the COVID-19 crisis have reported additional worry, stress, and overall negative impacts to their mental health. Such worry and stress may contribute to serious mental illnesses. Suicidal ideation and suicide have been shown to rise during times of heightened unemployment, and with unprecedented unemployment claims filed in New Hampshire since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, additional crisis interventions, support, and mental health care may be needed.[xxxi]

Substance misuse may also be exacerbated throughout this crisis. Treatment for those currently experiencing substance use disorders may be more difficult to access during the crisis, especially among those requiring group or community-based treatment. Substance use disorders have become more prevalent with higher levels of unemployment in the past, and other stressors may develop, including anxiety and general worry about the personal health and the health of loved ones requiring additional care and treatment in the future.[xxxii], [xxxiii]

Economic and Financial Challenges

Lower Income Earners and Individuals Experiencing Poverty or Food Insecurity

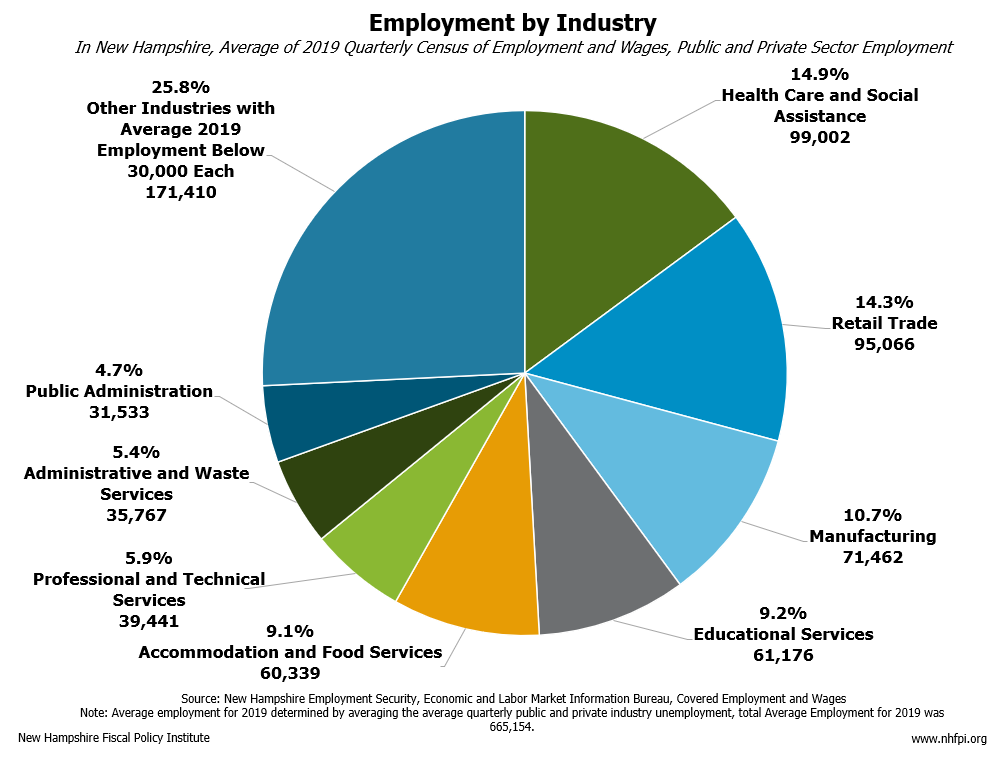

Individuals working jobs providing essential services during the pandemic, such as grocery store or health care operations, face increased risks of exposure to the virus and are more likely to be paid lower-than-average wages, based on statewide industry averages. For those working in industries unable to conduct business during this economic contraction, workplace shutdowns and job losses have affected workers, even with expanded and increased unemployment benefits. Workers with lower incomes are less likely to have sufficient resources to absorb any loss or lapse in income, or any additional expenses surrounding childcare, medical costs, or other increased expenses.

By 2019, before the COVID-19 crisis began, the average public and private sector weekly wage in the state was about $1,128. Of the top five largest industries, which comprised nearly 60 percent of employment in the state, four paid average wages lower than the statewide average. These industries were Healthcare and Social Assistance, comprising nearly 16 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $1,123; Retail Trade, also comprising nearly 16 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $653 dollars; Educational Services, comprising nearly 10 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $1,121; and Accommodation and Food Services, comprising over 10 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $434. Lower-than-average wages may result in these individuals being less able to build savings and, subsequently, less likely to recover from reduced income or job loss. Individuals earning lower wages are more likely to have fewer resources and may face additional challenges during these times in addition to increased exposure risk to the virus or employment loss. In New Hampshire, unemployment insurance claims data show that a majority of claims were generated by those working in industries which paid lower-than-average wages. This indicates that the negative employment and economic effects of the crisis have been most concentrated on individuals earning lower wages in New Hampshire.[xxxiv]

In April, the U.S. Census Bureau collected the first phase of weekly survey data targeted at understanding the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on households. This first phase of the weekly Household Pulse Survey was conducted from April 23 to July 21; during this phase, the data were released weekly and sought to measure the impacts of this crisis. Data collected through the first phase of the U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey estimated widespread income losses among Granite Staters since the pandemic began. Over these initial 12 weeks, nearly half of New Hampshire respondents reported a reduction in household income from employment since March 13, 2020. In mid-July, about one in five households expected a decline in income during the next four weeks because of the pandemic.[xxxv]

Individuals and families may be more likely to experience poverty or food insecurity, housing instability, limited access to health care, and other challenges moving forward. Along with the estimates for widespread income losses, the cost of many essentials, including food, has increased, and the access to other key services like childcare have been limited, due to the COVID-19 crisis.[xxxvi] Estimates for 2020 show the average rental rate for a two-bedroom apartment in the state rose to $1,413, with variations dependent on region, compared to the average rental rate for a two-bedroom apartment in 2019 of $1,347 per month.[xxxvii] The median home sale price increased 9 percent between May 2019 and May 2020 as well.[xxxviii] Additionally, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Consumer Price Index, which measures the prices paid for goods and services throughout the nation, food prices increased substantially relative to overall price changes. During the month of April 2020, the average price of food, specifically food purchased to prepare meals at home, increased 2.6 percent relative to the preceding month. In August 2020, the prices for food to prepare meals at home was 4.6 percent higher compared to the last 12 months. Additionally, in August 2020 the cost of medical care services increased by 5.3 percent compared to the last 12 months.[xxxix]

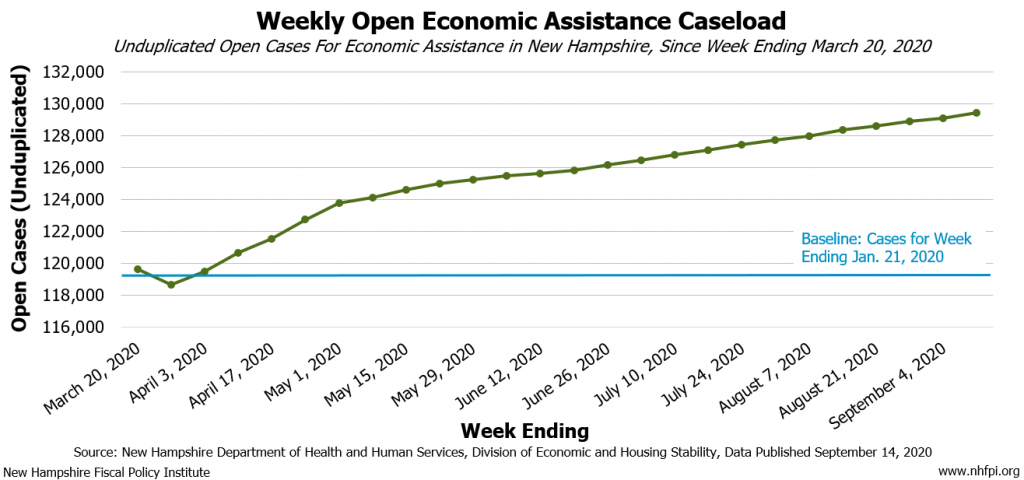

Increased Enrollment in Safety Net and Aid Programs

Changes in caseloads and enrollment in support programs in New Hampshire is a key indicator of the increased need for assistance as a result of the pandemic’s effect on lower-income Granite Staters. The number of unduplicated open cases for economic assistance has increased by nearly 10,000, from 119,424 on January 31, 2020, to 129,107 by September 4, 2020, representing an increase of over 8 percent. Economic assistance programs include Medicaid, nutritional aid, and other cash assistance.[xl]

Enrollment in Medicaid, which provides health care services to adults and children with limited resources, has increased during the COVID-19 crisis, indicating economic challenges are severe among these Granite Staters. Unduplicated cases for Medicaid in New Hampshire increased from 107,305 on January 31, 2020, to 117,527 by September 4, 2020, representing an increase of about 9.5 percent. The most recent breakdowns of Medicaid enrollment data show that individual enrollment in Medicaid has increased by 17,099 individuals, or nearly 10 percent, from January 31, 2020 to July 31, 2020. Notably, Medicaid enrollment among children increased by 4,559 children, or over 5 percent, over the same period. Enrollment specifically in expanded Medicaid, which covers adults aged 19 to 64 with low incomes, increased from January 31, 2020 to July 31, 2020 by 8,857, or over 17 percent, indicating that a significant portion of individuals earning lower incomes experienced negative economic impacts from the crisis severe enough to make them income-eligible for this program.[xli]

Enrollment in key components of another economic assistance program, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, increased as well. From the end of February to the end of August, the New Hampshire Employment Program, the largest cash assistance component of TANF designed to support those seeking work and training and their families, saw enrollment increase by 5.9 percent.[xlii] Other State TANF cash assistance programs for specific eligibility groups saw enrollment hold steady or decline. Alongside other components of the TANF program, TANF cash assistance provides help to families with incomes up to 60 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $1,086 per month for a family of three in 2020.[xliii]

Impacts on People of Color and Populations in Cities

People of color, including individuals identifying as Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, another non-white race, or two or more races are at heightened risk of negative health and economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis. Historic structural marginalization of groups identifying as non-white has contributed to higher numbers of individuals within these populations less able to mitigate physical interactions and less financially bolstered to weather economic downturns.[xliv] Median wages among individuals identifying as non-white or Hispanic are lower than those identifying as white and non-Hispanic, suggesting more individuals identifying as non-white work in lower wage industries that may leave workers more susceptible to negative effects of the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, certain non-white populations may be predisposed to certain chronic underlying health conditions, including asthma, making them particularly vulnerable to negative health effects of the 2019 novel coronavirus.[xlv]

Population density may have a major role in the spread of the virus. Individuals living in areas with greater population densities, where physical distancing is more difficult, may be more susceptible to contracting the virus. New Hampshire’s largest cities, Manchester and Nashua, have higher population densities than the state overall, and also face other challenges that may leave their populations more susceptible to the COVID-19 crisis. Compared to the state as a whole, these two cities had higher overall levels of poverty as well. While the poverty rate in the state was just under 8 percent in the 2014-2018 time period, the poverty rate in Nashua was nearly 10 percent, and in Manchester was nearly 15 percent.[xlvi] These elevated estimated poverty rates indicate that Granite Staters living in these cities have fewer resources to weather the economic effects of the crisis and are at elevated risk of contracting the virus. The most recent aggregated five-year data show that residents of Manchester and Nashua included approximately half of the total statewide population of individuals and families identifying as Black or African American and nearly half the population identifying their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino.[xlvii]

When analyzing COVID-19 cases in the state, the disproportionate impacts among certain non-white populations are apparent, similar to national trends.[xlviii] Despite estimates from 2019 showing those identifying as Black or African American and not Hispanic comprised about 1.5 percent of the state population, about 5.4 percent of all New Hampshire cases of COVID-19 were among Black or African American Granite Staters. A similar trend appears among individuals identifying as other non-white races, where COVID-19 cases are disproportionately prevalent.[xlix]

Current Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis

Federal and state policymakers have taken unprecedented steps to curb the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus, many of which have since expired. At the state level, initial actions to protect public health included: transitioning public schools to remote instruction during Spring 2020; closures of non-essential businesses; requiring residents to stay in their homes, with exemptions for certain activities related to food, caring for other individuals, and most outdoor recreation; prohibiting gatherings that exceed specified numbers of people; expanding access to telehealth services; providing additional funding to health care centers and certain health care workers; and establishing additional funding for social services programs focused on child care and victims of domestic violence. As of mid-September, the state has allowed several of these policies to sunset, including the stay at home order, the requirement for remote education, and limits on the sizes of public gatherings.

Additional actions taken at the state level provided support to those affected by the economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis and the efforts to mitigate the public health risk. Key gubernatorial orders included altering and waiving certain criteria for unemployment benefits and expanding these benefits to many more Granite Staters directly affected by the crisis throughout 2020, prohibiting most initiations of rental property eviction processes during the State of Emergency, forbidding foreclosures during the State of Emergency, and prohibiting disconnection or discontinuation of utility services. However, these key housing support programs were allowed to sunset at the beginning of July 2020.[l]

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services has also implemented additional temporary changes to programs that support lower income Granite Staters. These temporary changes aim to help ensure individuals and families can stay enrolled in programs including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or Food Stamp Program, TANF, and child care assistance throughout the crisis with a lowered risk of disenrollment due to program technicalities as incomes fluctuate, and difficulties in program redeterminations due to social distancing recommendations.[li]

Federal responses to the COVID-19 crisis have come in the form of four major pieces of legislation. These acts have provided additional support and funding for public health and direct aid to states; at least $1.6 billion from these four acts have been appropriated to the State and local governments in New Hampshire as of September 15, 2020.[lii] Additional federal actions include temporary expansions of unemployment eligibility, benefits, and family and medical leave; waivers allowing temporary benefit and continued eligibility changes to nutrition assistance programs; direct aid payments to many individuals; and emergency loans for small businesses, among other provisions.[liii] Upcoming federal and state level legislation may provide additional measures to support the health and economic wellbeing of individuals and families, and aid in an economic recovery.

Sustained Support Needed for Vulnerable Populations

Many Granite Staters were in need of additional care or support prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, and actions and investments made in the State Fiscal Years 2020-2021 New Hampshire State Budget were critical steps to help address some of the challenges faced by vulnerable population groups in the state. However, the COVID-19 crisis has extraordinarily exacerbated the necessity of support for these and other groups in the state.

The health risks and economic hardships may be the greatest on the most vulnerable groups of Granite Staters, such as individuals who are older, those with chronic health conditions, people with disabilities, individuals and families with lower incomes who are economically disadvantaged, and people of color. The COVID-19 crisis has also created a need for additional mental health care and substance use disorder treatment services. The extended economic shock has significantly impacted the revenues used to plan and fund State Budget expenditures. Significant efforts to raise additional revenue, along with the potential for additional federal aid, will be key to helping ensure continued and increased support needed for the vulnerable populations most impacted by this crisis.

New challenges and those exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis may be particularly acute on the health and economic wellbeing of many vulnerable Granite Staters. Ensuring Granite Staters in need continue to receive key support, including continuing previous investments in their access and quality of health care and vital aid programs as well as expanding aid to meet needs, will be essential during and after the crisis. Continued services to individuals and families affected by the COVID-19 crisis, through bolstered assistance and safety net programs, will help many Granite Staters in need weather this crisis and help create an equitable economic recovery.[liv]

Endnotes

[i] See NHFPI’s April 14, 2020 Issue Brief titled The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses, NHFPI’s June 30, 2020 Issue Brief titled Inequities Between New Hampshire Racial and Ethnic Groups Impact Opportunities to Thrive, and NHFPI’s September 4, 2020 Issue Brief titled Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[ii] Population age estimates are U.S. Census Bureau data prepared and published by the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau of New Hampshire Employment Security.

[iii] Yearly age demographic estimates are provided by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey’s Demographic and Housing Estimates.

[iv] See NHFPI’s March 15, 2019 Issue Brief titled Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Care Service Delivery Limited by Workforce Challenges.

[v] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Mental Health web page and the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 21, 2020 Issue Brief titled The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use for additional background on reported mental illness, depression, and other factors prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

[vi] Information on New Hampshire’s 10-Year Mental Health Plan is available from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

[vii] More information on substance use disorder in New Hampshire and the opioid crisis and response is available from the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Other Drugs.

[viii] See NHFPI’s September 4, 2020 Issue Brief titled Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[ix] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s recent release of various social and economic estimates representing 2019 titled Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2019.

[x] Information regarding poverty thresholds are published by the U.S. Census Bureau.

[xi] See estimates provided by the U.S. Census Bureau for 2019 in the report titled Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2019.

[xii] Poverty estimates for subsets of Granite Staters are representative of the five-year span from 2014-2018 to improve data reliability beyond the level of certainty provided by single-year estimates. The 2014-2018 five-year period is the most recent available five-year data published by the U.S. Census Bureau; additional information is available in NHFPI’s 2020 Conference Handout.

[xiii] See the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s September 2020 report titled Household Food Security in the United States in 2019 for additional discussion of the definitions of food insecurity and the most recent food insecurity estimates.

[xiv] See NHFPI’s October 9, 2019 Issue Brief titled The Potential Impacts of Proposed SNAP Eligibility and Work Requirement Changes on Food Insecurity for additional details on the negative impacts of food insecurity.

[xv] See the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey median household incomes by of renters and homeowners in New Hampshire in 2019.

[xvi] See the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s March 2020 Housing Market Report.

[xvii] See U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey median household incomes by of renters and homeowners in New Hampshire in 2019 and the cost burden definition provided in 2019 by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

[xviii] See the U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates Program.

[xix] Poverty estimates for subsets of Granite Staters are representative of the five-year span from 2014-2018 to improve data reliability beyond the level of certainty provided by single-year estimates. The 2014-2018 five-year period is the most recent available five-year poverty estimate data published by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey.

[xx] See NHFPI’s December 20, 2019 Issue Brief titled The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxi] For more information on the risks facing the health care and long-term care workforce, see the Kaiser Family Foundation’s April 23, 2020 Issue Brief titled COVID-19 and Workers at Risk: Examining the Long-Term Care Workforce.

[xxii] See NHFPI’s December 20, 2019 Issue Brief titled The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxiii] See NHFPI’s December 20, 2019 Issue Brief titled The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxiv] See NHPFI’s August 9, 2019 Common Cents post titled Continued Rise of NH’s Rental Costs Increases Financial Burdens on Residents.

[xxv] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Resource web page for older adults.

[xxvi] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Resource web page for individuals with certain medical conditions.

[xxvii] For an analysis of the number of adults at additional risk of negative health outcomes of COVID-19, see the Kaiser Family Foundation’s publications from April 23, 2020 titled How Many Adults Are at Risk of Serious Illness If Infected with Coronavirus? Updated Data.

[xxviii] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Resource page for people with disabilities.

[xxix] Disability estimates are published by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey’s Disability Characteristics for 2019.

[xxx] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 21, 2020 Issue Brief titled The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use for additional information on the additional challenges and risks for individuals requiring mental health care or substance use disorder treatment.

[xxxi] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 21, 2020 Issue Brief titled The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use for additional information on the additional challenges and risks for individuals requiring mental health care or substance use disorder treatment.

[xxxii] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 21, 2020 Issue Brief titled The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use for additional information on the additional challenges and risks for individuals requiring mental health care or substance use disorder treatment.

[xxxiii] For more information on the risks of increased substance misuse associated with unemployment, see Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Volume 142, September 2014 and Unemployment and Substance Use: A Review of the Literature (1990-2010), Current Drug Abuse Reviews, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2011.

[xxxiv] See NHFPI’s September 4, 2020 Issue Brief titled Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xxxv] See NHFPI’s September 10, 2020 Common Cents post titled New Data Show Food Insecurity Levels Declining Prior to the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xxxvi] See NHFPI’s September 4, 2020 Issue Brief titled Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xxxvii] Median rental costs are calculated by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority based on the annual residential rental cost survey. See the 2020 New Hampshire Residential Rental Cost Survey Report.

[xxxviii] For more information, see the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s Housing Market Snapshot for June and July 2020.

[xxxix] See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Summary updated September 11, 2020.

[xl] Economic assistance caseload data is published by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

[xli] Medicaid enrollment data is published by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

[xlii] Additional information on the New Hampshire Employment Program is available from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

[xliii] See the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Family Assistance Manual 601, Table B. Enrollment data provided in the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Caseload Reports.

[xliv] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Resource web page on Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups.

[xlv] Research conducted by Kaiser Health News provides insights into predispositions to certain conditions by race and ethnicity that increase the likelihood of negative health outcomes from COVID-19.

[xlvi] Poverty estimates for regions of New Hampshire are estimated over the five-year span from 2014-2018 to improve data reliability beyond the level of certainty provided by single-year estimates. The 2014-2018 five-year period is the most recent available five-year data published by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, and provides poverty estimates for 2014-2018 for Manchester and Nashua.

[xlvii] Demographic estimates for regions of New Hampshire are estimated over the five-year span from 2014-2018 to improve data reliability beyond the level of certainty provided by single-year estimates. The 2014-2018 five-year period is the most recent available five-year data published by the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, and provides demographic and housing estimates for 2014-2018 for Manchester and Nashua.

[xlviii] Analysis conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows the disproportionate health impacts of COVID-19 by racial and ethnic group.

[xlix] Population estimates by race and ethnicity in New Hampshire are published by the U.S. Census Bureau and COVID-19 infections, and COVID-19 cases are tracked on the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services COVID-19 Summary Dashboard, with these data reflecting information as of September 22, 2020.

[l] See the 2020 COVID-19 Emergency Orders page for a full list of the emergency orders enacted.

[li] Temporary eligibility and program changes to safety net programs have been published by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, and are discussed in an NHFPI Common Cents post published on April 3, 2020 and titled New Hampshire Expands Access to Safety Net Programs and Supports During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[lii] A full breakdown of COVID-19 federal funds as of September 15, 2020 has been published by the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant.

[liii] See NHFPI’s April 14, 2020 Issue Brief titled The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[liv] See NHFPI’s Common Cents post published April 29, 2020 and titled Key Policies Provide Short-Term Relief and Long-Term Recovery in COVID-19 Crisis.