This year has posed unprecedented challenges to New Hampshire’s workers and economy. The COVID-19 pandemic and crisis has contributed to significant changes in employment and has impacted the economic security of many Granite Staters. Despite positive trends in employment and the other indicators, which continued into early 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in New Hampshire created a severe public health emergency and has led to subsequent economic and employment fallout. This COVID-19 crisis is both a health and economic challenge, and continues to impact the lives of Granite Staters.

Unemployment in New Hampshire reached unprecedented levels in April 2020. This spike in unemployment levels was higher than any point during the Great Recession, which spanned 2007 to 2009. Unemployment continues to remain elevated throughout the state, and job losses have been greatest in certain service-based industries. These industries, which paid lower than average wages, along with regions of New Hampshire where large portions of employment are supported by tourism and leisure activities, have experienced the largest levels of employment loss, represented through claims for unemployment insurance.

These employment losses in New Hampshire have directly impacted the economic stability of many Granite Staters, particularly those who were earning lower or more modest incomes, and who worked in the most effected service-based industries. Many of those facing employment or income losses due to the impacts of this crisis have utilized key support programs, which have been temporarily expanded or created in an effort to help ensure individuals and families can make ends meet. Despite these expansions to certain support programs, other challenges in the state were both created and exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. The costs of housing and food have increased during this crisis, and limited access to and affordability of childcare has created additional financial and employment hardships for many New Hampshire residents and families.

This Issue Brief examines the recent employment landscape in New Hampshire, the employment impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on specific industries and regions of the state, comparisons of the current economic recession to past recessions, and discussions of the new and increased pressures facing Granite Staters who may be the most vulnerable and face the greatest risks to their economic stability.

Labor Landscape Overview Prior to the COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire

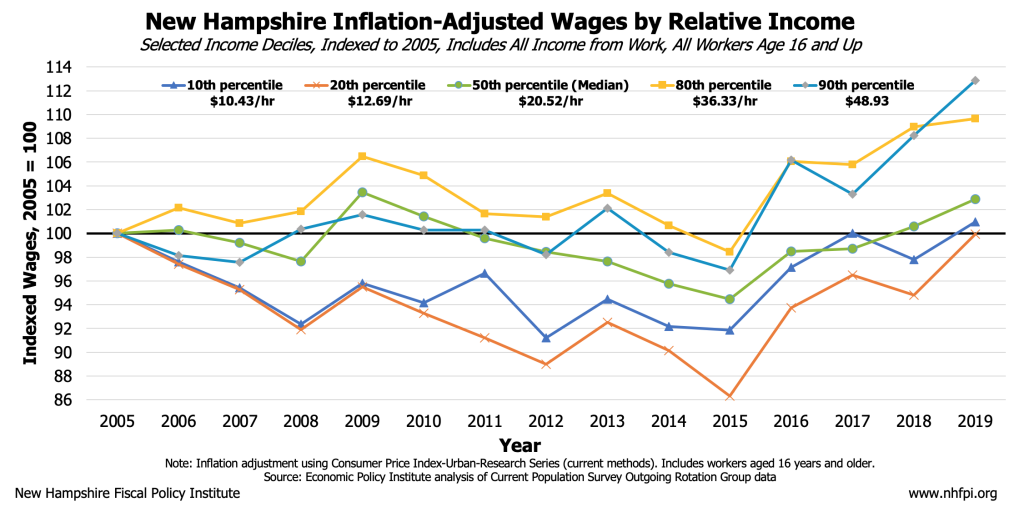

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, New Hampshire’s economy was experiencing positive growth based on several key measures. With unemployment at historically low levels, employment was increasing, albeit with higher levels of employment in certain lower-wage, service-oriented industries as compared to the years before the Great Recession.[1] Additionally, inflation-adjusted wages for nearly all workers had recovered to levels prior to the Great Recession. Notably, wages for individuals earning lower- and middle- incomes in New Hampshire only recently recovered to pre-Great Recession levels of purchasing power, while higher income earners experienced no clear decline in real wages during or after the Great Recession relative to before the downturn began.[2]

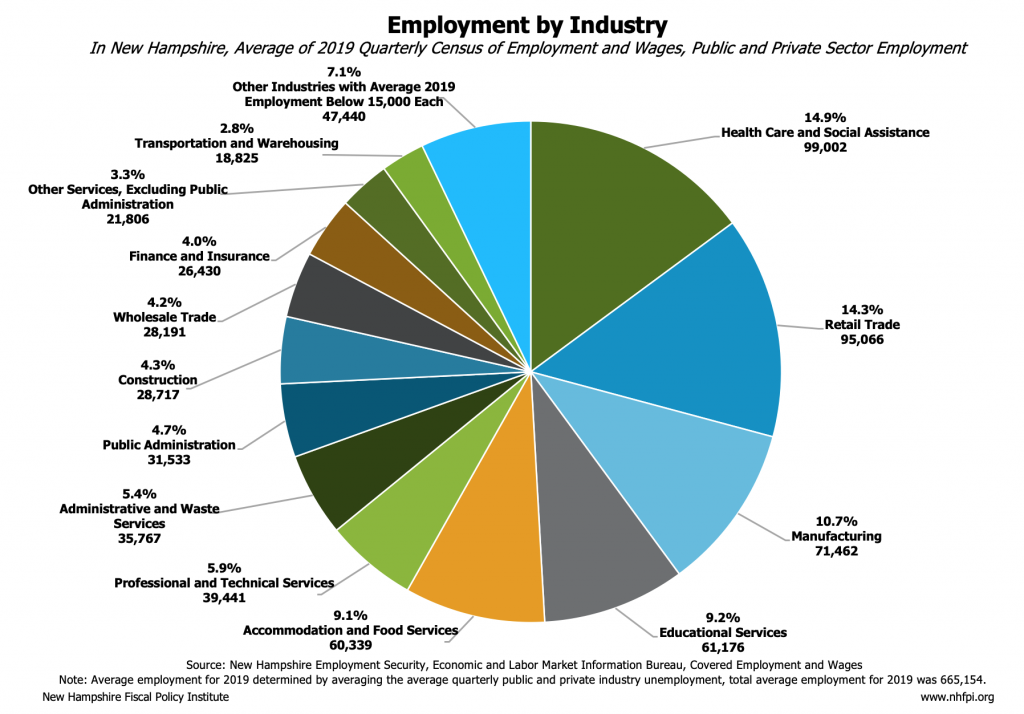

In 2019, overall employment in New Hampshire totaled 665,154 jobs, with an average public and private sector weekly wage in the state of $1,128. Of the top five largest industries, which comprised nearly 60 percent of employment in the state, only one of these industries had average weekly wages higher than the statewide average; that higher-wage industry was Manufacturing, with an average weekly wage of $1,404 and about 11 percent of total employment based in the state. The remaining four largest industries were Healthcare and Social Assistance, comprising nearly 16 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $1,123; Retail Trade, also comprising nearly 16 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $653 dollars; Educational Services, comprising nearly 10 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $1,121; and Accommodation and Food Services, comprising over 10 percent of employment in the state, with an average weekly wage of $434.[3]

The Economic and Labor Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis

The economic recession triggered by the COVID-19 crisis has led to more rapid declines in employment and economic activity than declines experienced during the worst of the Great Recession, which ended over a decade ago. With such considerable portions of employment in New Hampshire in service-based industries, the economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have been particularly acute among workers earning lower- and middle-income wages in such industries.[4] In an effort to understand how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting households, the U.S. Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey, which gathered data from April 23, 2020 through July 21, 2020, found that nearly half of all households in New Hampshire reported some loss of employment income since March 13, 2020. Additionally, estimates from this survey consistently found that at least one in five New Hampshire adults expected someone in their household to experience some loss of income from work in the subsequent four weeks.[5]

The challenges of the COVID-19 crisis also had disproportionate impacts on different racial and ethnic groups, and on women. According the national-level research, employment compositions by race and ethnicity in many of the most impacted industries are disproportionately non-white individuals. This disproportionate concentration is partially reflected through higher national unemployment rates among certain groups, including Black or Hispanic individuals.[6] Additionally, in New Hampshire, the share of unemployment attributed to women is estimated to be higher than any time within the last 20 years. Data released by NHES show that, from April to June 2020, about 58 percent of the people unemployed in New Hampshire were women.[7]

Unemployment and Labor Force Changes

The economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis are represented most notability through employment losses and labor force changes. Due to the rapid onset of the economic effects of this crisis, these data are likely to be revised, potentially significantly, as additional data are collected monthly. Despite the potential for revisions, estimates for employment provide a high-level account of the impacts.

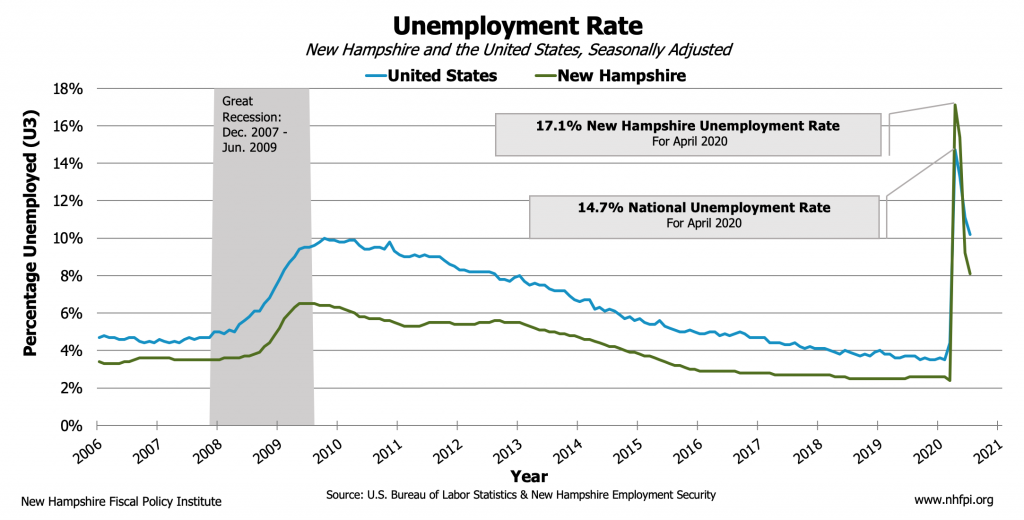

Overall levels of unemployment in New Hampshire increased rapidly after measures were taken in mid-March to respond to the pandemic at both the state and federal levels. The unemployment rate in New Hampshire increased to 17.1 percent in April 2020, much higher than any point during the Great Recession, and exceeding the 14.7 percent national unemployment rate for that month. Both rates have declined rapidly in the time since then. However, the unemployment rate for July 2020 in New Hampshire was estimated to be 8.1 percent, which is still higher than any point experienced during the Great Recession or the slow economic recovery that followed.[8]

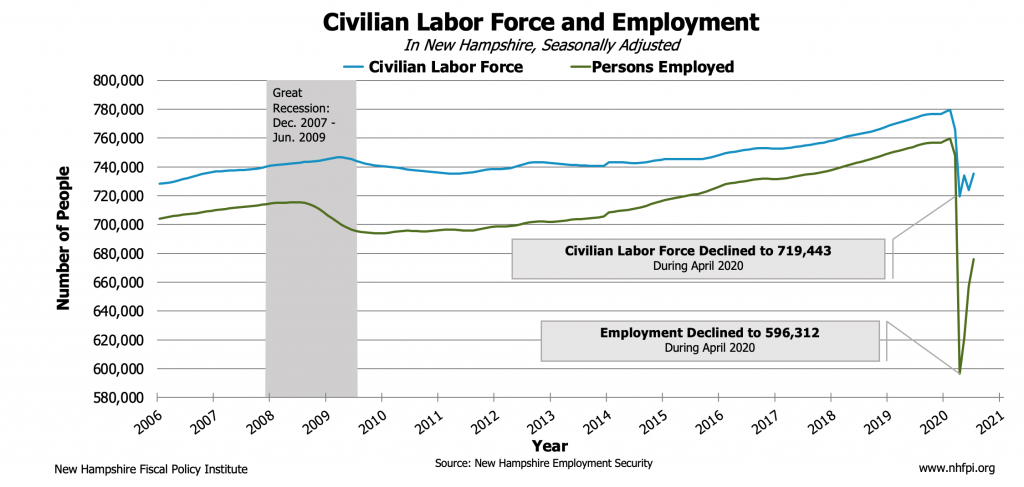

The labor force and total employment in New Hampshire have also declined significantly as a result of the COVID-19 crisis and recession, with the lowest levels experienced during April 2020. During that month, the civilian labor force, which represents all people age 16 and older who are employed or unemployed, declined to 719,443 persons, which is lower than any level in the last 15 years.[9] Unemployed individuals in the labor force, who are represented by the unemployment rate, only include those who are not employed, are available for work, and have actively searched for a job in the last 4 weeks or are expecting to be called back to work after a temporary layoff.[10]

The large decrease in the civilian labor force may indicate that a larger portion of workers in New Hampshire, potentially including some of those who experienced job losses, are not actively seeking new work, and are not expecting that their job losses are only temporary. Among other factors, this decline in the labor force’s size could be due to people who are at increased health risk from the virus seeking to avoid exposure at a workplace, or those who are caring for family members, such as children or older adults, who cannot provide such care and work at the same time. Additionally, as expected in conjunction with increased levels of unemployment, employment in New Hampshire declined to 596,312 jobs in April 2020, lower than any point in at least the last 15 years. As of July 2020, employment is still suppressed compared to prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis and any period experienced during or immediately after the Great Recession.[11]

Unemployment Insurance Utilization

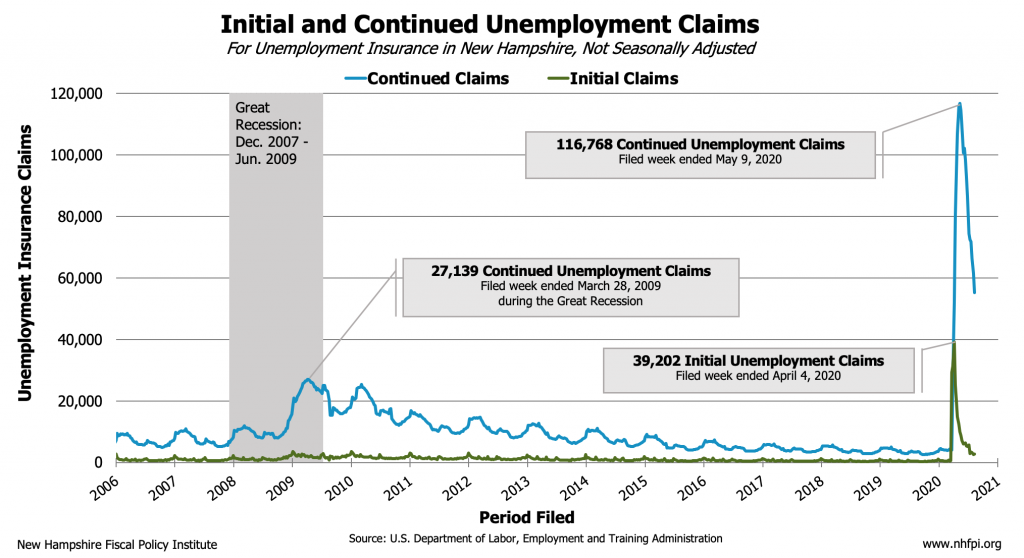

In response to the economic and employment impacts of the COVID-19 crisis and recession, unemployment insurance benefits eligibility was expanded to encompass more workers, including those working part time and those who are self-employed. These actions were designed to help support workers in New Hampshire, especially among industries that were most impacted due to the inability to adapt to a work model that limits physical interactions. Initial unemployment claims, which are reported weekly, peaked in New Hampshire for the filing week ending April 4, 2020. New claims during this week totaled 39,202. The most recent data available show that initial claims have tapered off, but still totaled over 2,000 new claims during the first week of August, compared to 467 initial claims during the first week August 2019.

Continued claims, which are also reported weekly, represent the unemployment claims that were recertified each week to continue benefits. The highest level of continued claims occurred for the filed week ending May 9, 2020, where 116,768 unemployed workers in New Hampshire had filed continued claims for benefits. This represented a 2,857 percent increase in continued claims compared to those filed during the week before the economic and employment impacts of the COVID-19 crisis began. Continued claims this week were over 330 percent higher than the peak number filed during any week of the Great Recession or its aftermath. Continued claims have declined significantly since the peak in early May, but are still elevated in mid-August. Recent weekly data shows that, for filed week ending August 15, 2020, continued claims totaled 49,836, which is still about 83 percent higher than the peak number of continued claims filed during any week of the Great Recession.[12]

Differing Impacts on Industries and Counties

While unemployment rose to unprecedented levels across the nation and in New Hampshire initially during April 2020, the impacts of the crisis were targeted more acutely among certain industries and regions. The recession caused by the COVID-19 crisis has been more swift and severe than economic downturns in the recent past, as unemployment and income losses increased immediately as a result of actions taken to mitigate health risks for many Granite Staters. Key support programs, like expanded unemployment insurance, provided supplemental income to assist workers to make ends meet.[13]

Service-Based Industries Most Affected

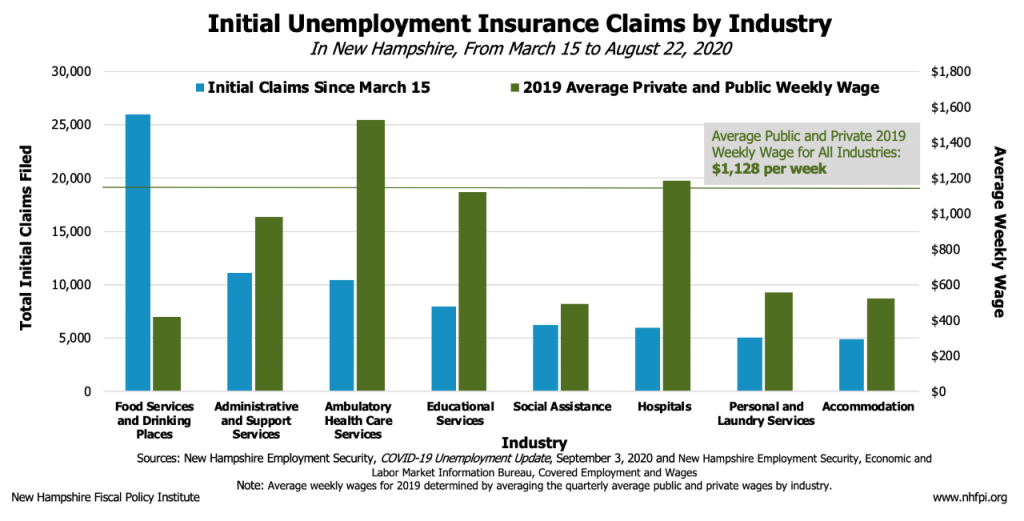

Nationally, research on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis and recession shows that most of the direct effects have been among key service-based industries, where transitions to remote work have not been feasible given the type of services provided, or among service-based industries where demand for services declined.[14] A significant portion of the jobs in New Hampshire are in industries dependent on physical interactions with the public, including industries that pay lower average wages, such as food services. With physical interactions curtailed to slow the spread of the virus, the negative economic consequences of the crisis are most concentrated in these industries.[15] To understand the magnitude of the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis and recession in the state, New Hampshire Employment Security (NHES) has released weekly updates regarding

unemployment claims broken down by industry.

New Hampshire workers employed at Food Services and Drinking Places, such as restaurants and bars, generated the largest number of claims from any industry over the period beginning on March 15, 2020, when the economic and employment effects of the crisis began, through August 22, 2020. Over this period, 25,986 initial claims were filed solely in this industry. The average weekly wage among workers in this industry was only about $419, compared to the statewide 2019 public and private sector average weekly wage of about $1,128. The industry with the next largest number of initial unemployment insurance claims generated was Administrative and Support Services, with 11,127 claims. The average weekly wage in this industry during 2019 was $982, also below the statewide 2019 public and private sector average weekly wage. According to the data released by NHES, of the eight industries that generated the most initial unemployment claims, six paid lower than average wages. This may indicate that most of the employment impacts felt by workers in New Hampshire were among those earning lower than average wages.[16],[17]

County-Level Disparities

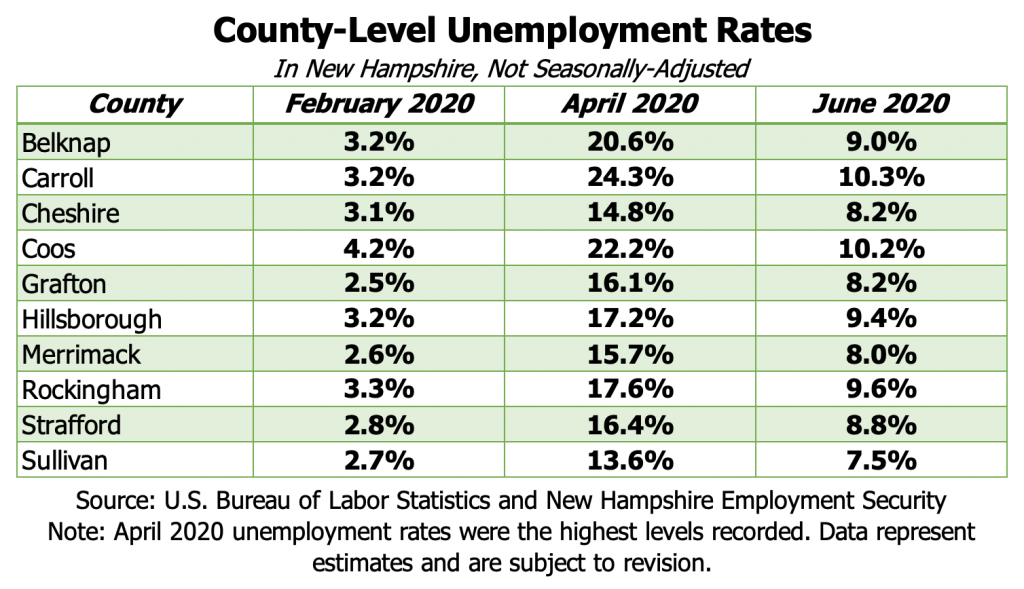

Industry-level economic and employment impacts have not been uniformly distributed throughout the state. Given the economic differences between New Hampshire’s counties, along with the differing compositions of employment within in each county, some regions of the state may have been more intensely impacted than others. Northern and western regions of the state, which rely more heavily on tourism to support their economies, experienced higher peak unemployment rates during April 2020. Carroll County, which experienced the highest levels of seasonally unadjusted unemployment during the crisis so far, had over 20 percent of county employment in the Accommodation and Food Services industry in 2019. This large employment sector, which paid weekly wages far below the statewide average, was more susceptible to the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. Counties which had lower levels of employment in certain service-based industries, including Accommodation and Food Services, experienced lower levels of unemployment during April 2020.[18]

Risks to the Economic Stability of Workers

The severity of the COVID-19 crisis and recession has resulted in swift negative impacts on the economic wellbeing of many workers in New Hampshire. Prior to this crisis and recession, individuals earning lower- and middle- incomes in New Hampshire had only recently experienced wage growth that pushed inflation-adjusted wages back to levels seen prior to the Great Recession, while individuals earning higher incomes experienced no significant aggregate wage decline during the recovery from the Great Recession and had significant wage growth in the final years of the recovery.[19]

This combination of a latent wage recovery and growth for lower- and middle-income workers in New Hampshire, along with employment shifts during the economic recovery from the Great Recession, may indicate that significant portions of workers in New Hampshire are vulnerable to the impacts of this crisis. Those directly impacted by a job loss, or indirectly impacted by other negative economic effects of this crisis who work in a lower-paying industry, may have been the least prepared to weather this crisis and may face the greatest risks to their economic stability.[20] Additionally, several key economic challenges present before the COVID-19 crisis and exacerbated by it, as well as those created by the COVID-19 crisis, may present particular hardships for those most effected by employment or income losses.

Increased Housing Costs

Affordable housing has become increasingly difficult to secure in New Hampshire in recent years. The challenge of securing stable and affordable housing has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, as the prices for apartments and homes have risen dramatically, due to both decreased supply and shifts in market demand. Estimates for 2020 show the average rental rate for a two-bedroom apartment in the state was $1,413, with variations dependent on region, compared to the average rental rate for a two-bedroom apartment in 2019 of $1,347 per month.[21] Additionally, the median home sale price increased 9 percent between May 2019 and May 2020 as well.[22]

Childcare Access and Affordability

Childcare availability and affordability were existing challenges in the state, and have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis.[23] According to national research, schools transitioning to remote learning and a lack of childcare opportunities place additional burdens on working parents, typically requiring reductions to work and employment. The same research also shows that this reduction in work due to childcare limitations disproportionately falls on women.[24] In New Hampshire, the share of unemployment attributed to women is estimated to be higher than any time over the last 20 years, suggesting this factor may contribute to higher unemployment among women. Data released by NHES show that, from April to June 2020, about 58 percent of the people unemployed in New Hampshire were women.[25] Additionally, national estimates show about one in five childcare workers have lost their job, potentially leading to a more limited supply of childcare in the future and creating further hardships for parents.

Rising Cost of Key Goods and Services

The increased cost of food and key goods presents another significant challenge to Granite Staters. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Consumer Price Index, which measures the prices paid for goods and services throughout the nation, food prices increased substantially relative to overall price increases. During the month of April 2020, the average price of food, specifically food purchased to prepare meals at home, increased 2.6 percent relative to the last 12 months. By July 2020, the prices for food to prepare meals at home increased by 4.6 percent compared to a year earlier. Additionally, in July 2020 the cost of medical care services increased by 5.9 percent compared to a year earlier.[26] These increases in the costs of key goods and services may indicate additional financial challenges for lower- and middle-income Granite Staters during a time of increased and unprecedented levels unemployment, heightened risk of economic instability, and health risks.

Concluding Discussion

The COVID-19 crisis has impacted the New Hampshire economy and workers in unprecedented ways. Employment in New Hampshire over the past year has shifted rapidly from expanding with a growing economy to a severe crisis and recession. The economic stability of many Granite Staters, particularly those with lower incomes and fewer resources who have only recently recovered from the Great Recession, may be significantly impacted. This crisis has spurred a sharp recession, which has drastically impacted the employment and incomes of many Granite Staters. Survey data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that nearly half of all households in the state have reported a loss of income from employment since the onset of the crisis in mid-March, and a smaller portion of households expected to lose income in the subsequent month.

While indicators of risks to worker well-being, such as unemployment and unemployment insurance claims, have begun to decline since the unprecedented peak levels were reached in April 2020, the number of Granite Staters out of work remains elevated. Recent data indicates fewer people are employed, and fewer of those who are unemployed are expecting their job to return or searching for a job. Additionally, the industries and regions of the state that were most impacted, in terms of employment loss, were those industries which paid lower than average wages and those regions where employment was comprised of larger portions of certain service-based industries. This may indicate that most of the employment impacts felt by workers in New Hampshire were among those earning lower than average wages.

The challenges facing many Granite Staters have continued as industries most impacted by the COVID-19 crisis began recovering. Employees in these industries continue to face economic and health risks and may rely on key support programs, including expanded unemployment insurance and additional nutritional aid, to provide vital support. However, the expirations and reductions in aid of these key support programs may be detrimental to the economic stability of many Granite Staters.

Recovering from the economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis will require supporting those with the fewest resources and those who are most impacted. Additional programs to help ensure that Granite Staters can access sufficient aid, through programs such as expanded unemployment insurance and nutritional programs, should be paramount. Assisting those with the fewest resources and those most impacted may have another significant impact through the form of economic stimulus to hasten the recovery of the economy overall.[27] Policies to help ensure Granite Staters can make ends meet may stimulate the economic recovery, reduce the potential for downward economic mobility, and build a more equitable economy for New Hampshire.

Endnotes

[1] For more information on trends and analyses of the recovery period after the Great Recession, see NHFPI’s August 2019 Issue Brief titled New Hampshire’s Workforce, Wages, and Economic Opportunity and NHFPI’s April 2019 Issue Brief titled The COVID19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[2] State-level data used to analyze these figures have been compiled by the Economic Policy Institute and represent analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group data.

[3] Average employment and industry-level weekly wages for 2019 were determined by averaging the average quarterly public and private industry unemployment and wages for the four quarters of 2019. Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Covered Employment and Wages.

[4] See the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Issue Brief titled The Effects of the Novel Coronavirus Pandemic on Service Workers in New England, published March 31, 2020.

[5] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic – Household Pulse Survey.

[6] Information on the disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 crisis by race and ethnicity is available in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ June 2, 2020 report titled The Impact of the COVID19 Recession on the Jobs and Incomes of Persons of Color and the Urban Institute’s May 6, 2020 UrbanWire post titled How COVID-19 Is Affecting Black and Latino Families’ Employment and Financial Well-Being.

[7] For more information see New Hampshire Employment Security’s August 20, 2020 COVID-19 Unemployment Update.

[8] Unemployment data compiled from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics program and Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, and Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Labor Force and Unemployment.

[9] Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Labor Force and Unemployment. Data for 2020 is are subject to revision and are not yet benchmarked.

[10] Labor Force definitions are available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[11] Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Local Area Unemployment Statistics. Data for 2020 are not yet benchmarked.

[12] Updated advance and initial unemployment claims are released by the U.S. Department of Labor each Thursday.

[13] For discussions on unemployment changes and overall utilization and importance of unemployment insurance for financial support, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ June 9, 2020 report titled CARES Act Measures Strengthening Unemployment Insurance Should Continue While Need Remains.

[14] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ analysis of Goldman Sacs projections for industries most impacted by the onset of the COVID-19 crisis.

[15] For more information see NHFPI’s April 2019 Issue Brief titled The COVID19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[16] Data on unemployment claims by industry and other key employment and unemployment data are published weekly by New Hampshire Employment Security.

[17] Average employment and industry level weekly wages for 2019 were determined by averaging the average quarterly public and private industry wages for the four quarters of 2019.

[18] County level unemployment statistics and employment by industry estimates are published by New Hampshire Employment Security. Data are subject to revision.

[19] State-level data used to analyze these figures have been compiled by the Economic Policy Institute and represent analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group data.

[20] See NHFPI’s April 2019 Issue Brief titled The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[21] Median rental costs are calculated by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority based on the annual residential rental cost survey. See the 2020 New Hampshire Residential Rental Cost Survey Report.

[22] For more information, see the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s Housing Market Snapshot for June and July 2020.

[23] For more information on childcare access and affordability challenges, see the University of New Hampshire Carsey School for Public Policy’s August 24, 2020 report titled COVID-19 Didn’t Create a Child Care Crisis, But Hastened and Inflamed It.

[24] See the National Women’s Law Center’s August 2020 Fact Sheet titled One in Five Child Care Jobs Have Been Lost Since February, and Women Are Paying the Price.

[25] For more information see New Hampshire Employment Security’s August 20, 2020 COVID-19 Unemployment Update.

[26] See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Summary updated August 12, 2020.

[27] For more information on the effectiveness of public support programs at creating economic stimulus, see NHFPI’s April 21, 2020 Common Cents post titled Food Assistance Programs Provide Critical Relief and Boost the Economy and April 29, 2020 post titled Key Policies Provide Short-Term Relief and Long-Term Recovery in COVID-19 Crisis.