KEY POINTS

- The new State Budget appropriates $15.89 billion and funds most State agency operations with higher appropriations, unadjusted for inflation, but makes some reductions in services

- The most significant new funding initiatives include boosting retirement benefits for certain police and firefighting public employees, increasing funding for special education and lower-property value school districts, and increases in funding for Education Freedom Accounts, regional drinking water infrastructure projects, and nursing facilities

- Funding was reduced at the University System and for several key smaller health and justice agencies, including the Office of the Child Advocate, the Human Rights Commission, the Housing Appeals Board, the State Commission on Aging, and family planning, tobacco cessation, and prescription drug affordability efforts

- Expanding legalized gambling, including video lottery terminals, and increases in dozens of fees will bolster State revenue

- Work requirements and increased premiums and copayments for certain Medicaid enrollees, pending federal approval, may limit access to health care

- Other policy initiatives include expansions to maternal health supports, prohibitions on certain diversity, equity, and inclusion activities in governments, a cell phone ban in schools, and repealing vehicle inspections

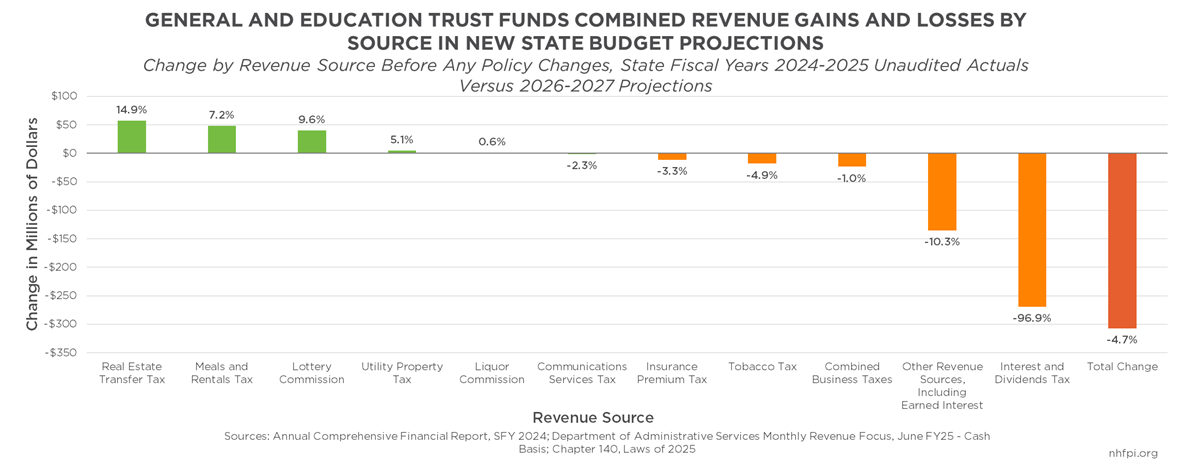

The new two-year State Budget will fund State-supported services in an uncertain financial and economic environment. Policymakers faced significant potential costs, and recent substantial decreases in State revenue required more tradeoffs in the new State Budget than when policymakers were crafting the prior budget in 2023. The revenue decreases have been primarily the result of slower growth in national corporate profits, which accelerated substantially in the years following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and State policy choices that have reduced revenue, including the elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax in 2025.[i]

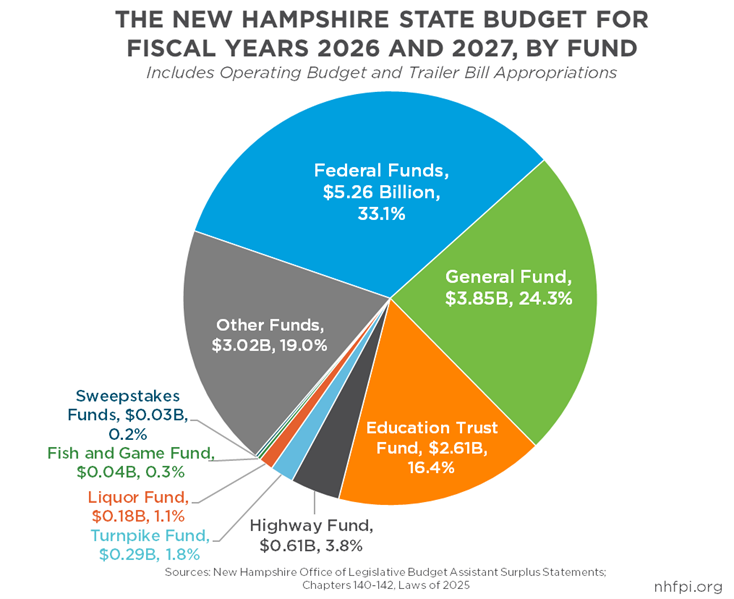

Policymakers also faced considerations of expenditure needs and federal policy changes that will impact Granite Staters over the next two years. While the costs for delivering existing State services continue to increase, other one-time and less predictable expenses could upend the new State Budget. These expenses include costs associated with both settlements and court cases stemming from decades of alleged abuses of children in the State’s care at the former Youth Development Center and contracted agencies, as well as any changes to federal funding that reduce resources available for the State of New Hampshire or its residents. Nearly one-third of the dollars funding the new State Budget are federal funds, totaling $5.26 billion during State Fiscal Years (SFYs) 2026 and 2027, which is a typical level of reliance on federal funds for the New Hampshire State Budget.[ii]

While federal policy changes and potentially consequential State Supreme Court decisions related to education funding came after the passage of the new State Budget, policymakers did include some consideration of certain looming expenses, as well as new initiatives, in the State Budget. Boosts to retirement benefits for certain police and firefighter public employees, increases in aid to local public schools, adding funding for Education Freedom Accounts, expansions of legalized gambling, and requiring specific maternal mental health supports are key examples of new initiatives in the State Budget. However, reductions in funding for certain public health and child wellbeing efforts, public higher education, and unspecified cuts in State agency budgets will impact services in ways that are difficult to predict. Additionally, both Medicaid premiums and work requirements will limit access to health care for Granite Staters with low incomes.

This Report examines the State Budget for State Fiscal Years (SFYs) 2026-2027 enacted in June 2025. This report reviews topline figures associated with expenditures in the new State Budget, as well as spending and policy changes in each key policy area of the State Budget. This Report provides context for key policy areas that receive support through the State Budget and reviews the revenue projections and policy changes supporting the State’s operations for the next two years.

While this Report focuses on the changes made in this State Budget relative to the prior State Budget, some funding comparisons are made only to the second year of the previous State Budget (SFY 2025) due to differences in the availability of figures that reflect actual appropriations. Specifically, the SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget’s accounting, as enacted, did not incorporate a significant State employee pay increase into individual agency budget lines, and also did not incorporate Medicaid reimbursement rate increases into relevant budget lines, so comparisons would artificially inflate appropriation increases in the new State Budget.[iii]

Summary of Significant Changes

The new State Budget for SFYs 2026-2027 maintains current, or near to the current, levels of services provided by most State agencies with $15.89 billion in appropriations. However, it includes some significant changes to programs and agency structures, particularly for some smaller agencies. Cost growth was relatively constrained across the entire new State Budget, relative to recent rates of inflation. Many one-time appropriations from the prior State Budget, including key investments in housing, were not repeated in the new budget. Several targeted funding increases will boost specific programs, but funding reductions in other areas and other restrictions on access to benefits could limit services for Granite Staters relative to the prior State Budget.[iv]

Changes to appropriations and policies in the new State Budget include:

- Boosting funds to the New Hampshire Retirement System to increase benefits for certain police and firefighting public employees, particularly those who had anticipated Retirement System benefits altered after modifications in 2011, with a $42.0 million appropriation during the biennium

- Expanding available Special Education Aid for school districts, allocating an additional $32.0 million (47.2 percent) toward Special Education Aid relative to the current State Budget’s appropriations for a total of $99.8 million over the biennium, and guaranteeing a higher funding level for school districts than prior law

- Increasing funding to Education Freedom Accounts after a policy change in separate legislation lifted the income limitations, and modifying a new cap on components of program enrollment

- Modifying the State’s education funding formula to provide more aid to schools with lower amounts of taxable property value per student in their communities

- Prohibiting initiatives, programs, and contracts related to diversity, equity, and inclusion for governments, including the State, city and town governments, county governments, and school districts, with a risk of the elimination of State funding for a publicly-funded school or academic institution if it is noncompliant

- Requiring school districts to prohibit cell phone use by students during the school day

- Decreasing the State Budget’s appropriated funding for the University System of New Hampshire by $35 million (17.6 percent) relative to the prior State Budget

- Reducing funding for the Office of the Child Advocate, the State Commission on Aging, the Human Rights Commission, the State’s Division of the Arts, and the Housing Appeals Board

- Defunding the Tobacco Prevention and Cessation Program, as well as repealing the Prescription Drug Affordability Board and certain State rulemaking authority related to vaccine requirements

- Adding premiums for some Medicaid enrollees, including Granite Advantage enrollees and Children’s Health Insurance Programs with certain income levels, and increasing copayments for prescription drugs for Medicaid enrollees, pending federal approval of these changes

- Adding work and community engagement requirements for adults enrolled in the Granite Advantage portion of the Medicaid program through the resubmission of a request to the federal government to permit requiring 100 hours per month of eligible activities for continued enrollment, which is more than the newly authorized work requirements in the federal reconciliation legislation

- Increasing funding for nursing facilities and drawing on dedicated funding for developmental services carried forward from unspent funds in prior years

- Decreasing payments to hospitals for uncompensated care relative to the prior State Budget

- Requiring Medicaid and private insurance to cover certain maternal health activities, including perinatal depression screenings and home visiting services, while also providing funding for rural maternal health emergency services training and requiring certain larger employers to provide up to 25 hours of protected unpaid postpartum care and pediatric appointments

- Increasing funding for housing shelter services, including at least $15 million for a combination of both higher reimbursement rates for shelters and support for individuals experiencing homelessness related to opioid addiction or another substance use disorder

- Eliminating 54 positions at the Department of Corrections

- Increasing motor vehicle registration fees, certain fees for projects or activities with environmental impacts, agricultural fees, court fees, and nursing facility licensing fees among a total of 131 increased fines, fees, and other charges associated with certain programs established in State law

- Repealing the State’s legal requirements for motor vehicle inspections in two phases during 2026, dependent in part on an agreement with the federal government regarding emissions regulations

- Appropriating funding for regional water infrastructure projects, including in the southeastern part the state with groundwater impacted by certain contaminants

- Allocating $20 million to the fund supporting settlements related to the Youth Development Center, as well as $10 million as part of an agreement from one Youth Development Center-related court case

- Expanding opportunities for legal gambling in New Hampshire, including video lottery terminals

- Prohibiting the sale or lease of land in New Hampshire to certain foreign governments or individuals or entities related to those governments in certain ways, including the governments of China, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and Syria

- Requiring State officials to find $112.7 million in budget savings during the biennium, including appropriation reductions for specific departments and a general requirement for finding savings or new revenues within the Executive Branch

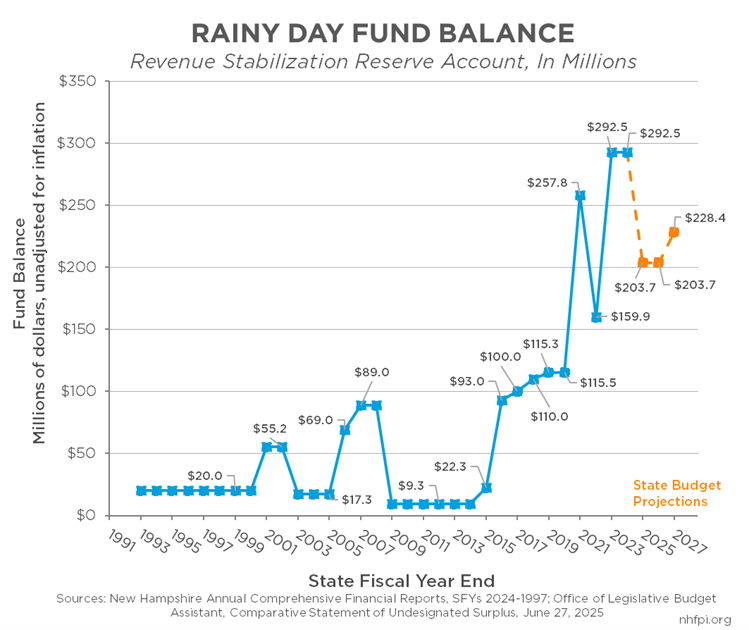

The State Budget funds these service changes with no major changes in existing taxes, but expanded revenues through gambling activities and fee increases support the increased expenditures. The new State Budget is projected to leave $24.7 million in unspent State funds to add to the Rainy Day Fund at the end of SFY 2027, which would bring the Rainy Day Fund to a projected balance of $228.4 million, the fourth-highest year-end total in the Fund’s history.

Changes to Budget Totals and By Category

The new State Budget authorizes $15.89 billion in expenditures from all funds for SFYs 2026 and 2027 combined. That total includes about $87.5 million in Trailer Bill and companion legislation appropriations, $112.7 million in unspecified back-of-budget reductions, and $80.0 million in funds authorized by an organization note in the Operating Budget Bill for use during the biennium out of the Developmental Services Fund, the Acquired Brain Disorder Services Fund, and the In-Home Support Waiver Fund.[v]

Total appropriations in this new two-year State Budget increase by $475.1 million (3.1 percent) from the $15.42 billion appropriated by the SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget, adjusted for accounting differences between the two budgets but unadjusted for inflation. While future inflation is difficult to forecast accurately, inflation faced by consumers in New England was 2.7 percent during SFY 2025 and 3.8 percent in SFY 2024.[vi] The SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget included significant one-time expenditures, but also funded certain ongoing services that the new State Budget either curtails or shifts to draw on funding sources outside of the new State Budget biennia.[vii]

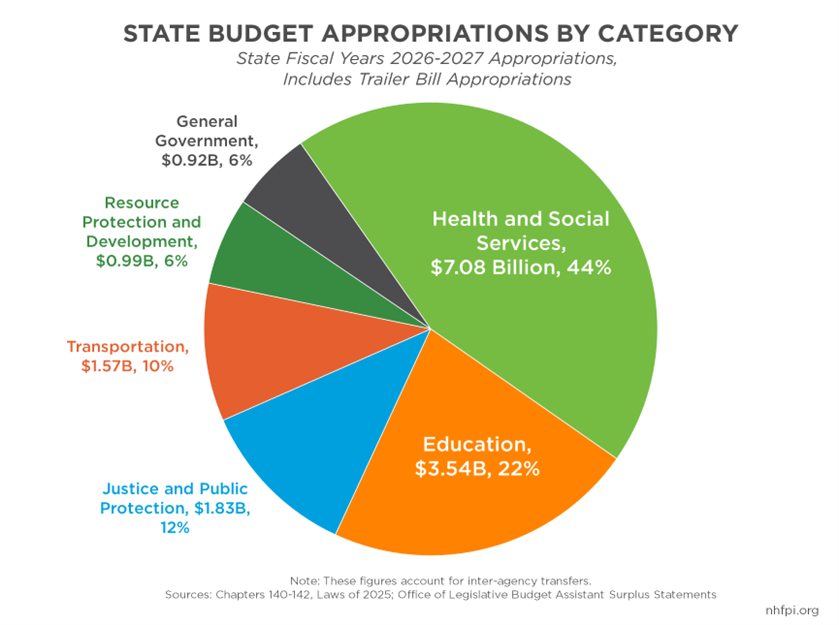

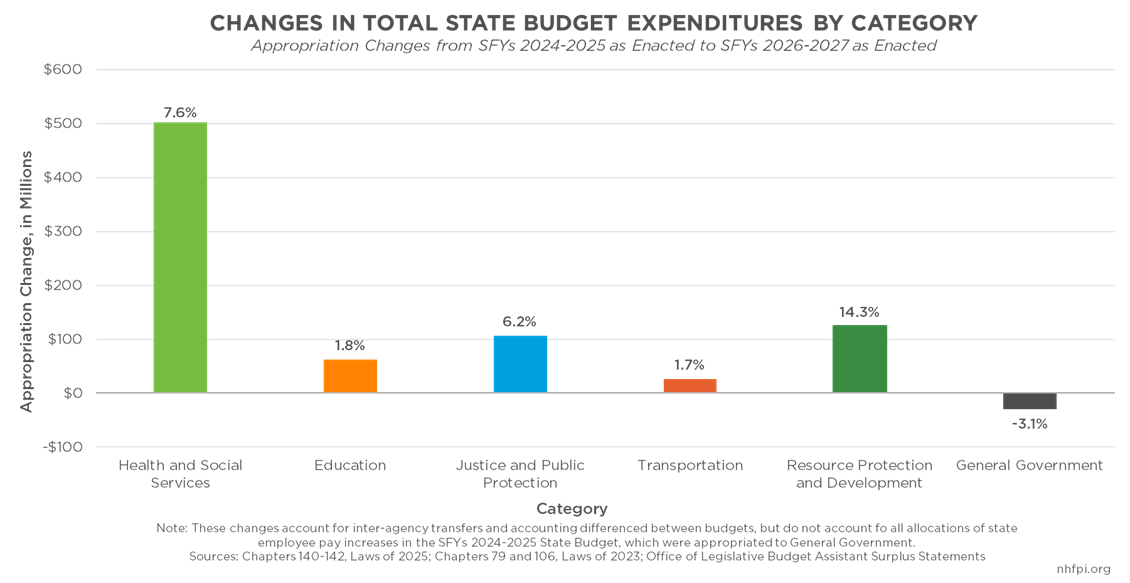

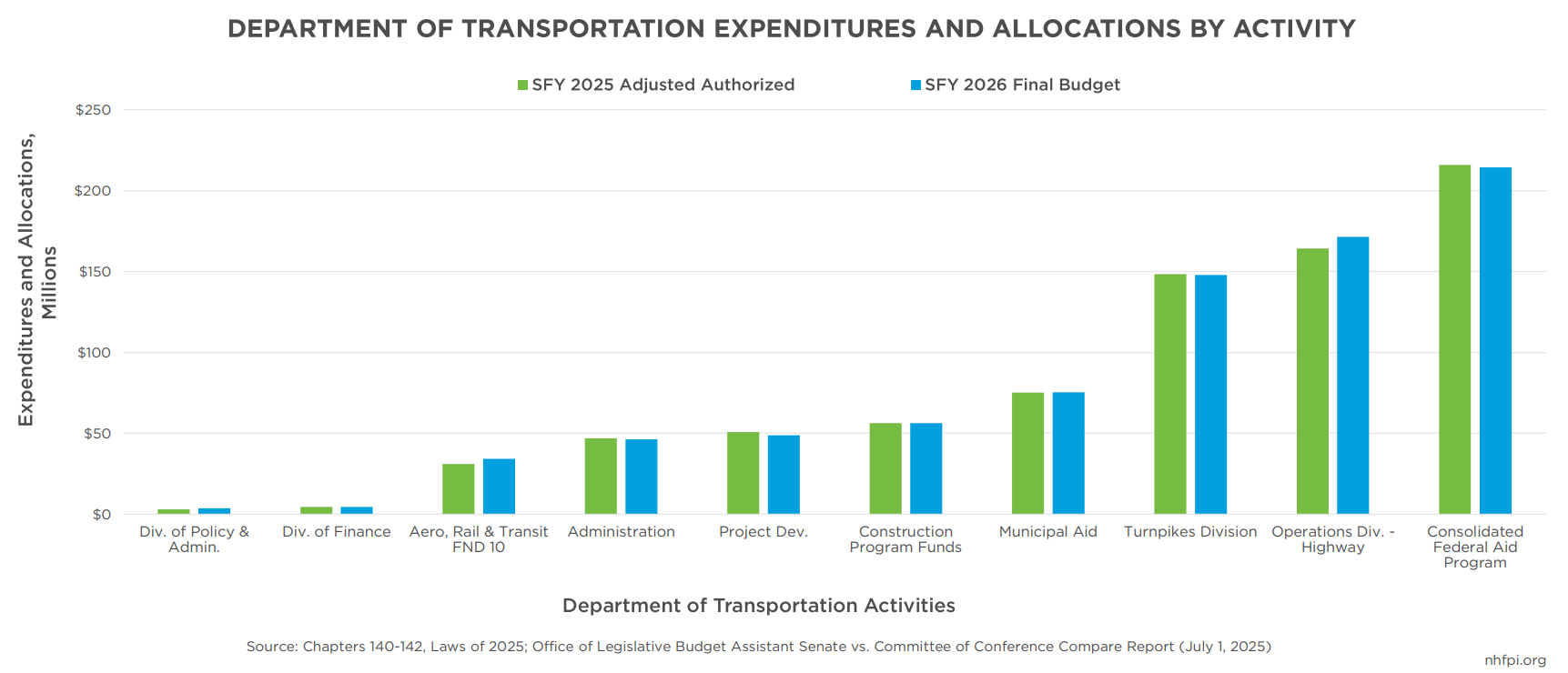

While the overall budget grows, not all service areas grew equally. All expenditures in the State Budget are divided into six categories covering broad service areas. Changes in these six categories provide a high-level indication of shifts in spending across government activities. The six categories, in order of appropriation size in the New Hampshire State Budget, are: Health and Social Services, Education, Justice and Public Protection, Transportation, Resource Protection and Development, and General Government. About two-thirds of State Budget appropriations are allocated to the Health and Social Services or Education categories.

In the new State Budget, the largest aggregate funding increase among the categories flows to the Health and Social Services category. While accounting decisions limit comparisons between the two budgets by categories and State agency detailed levels, approximately $502.2 million (7.6 percent) more has been appropriated to the Health and Social Services category for SFYs 2026-2027 than were in SFYs 2024-2025, unadjusted for inflation.[viii]

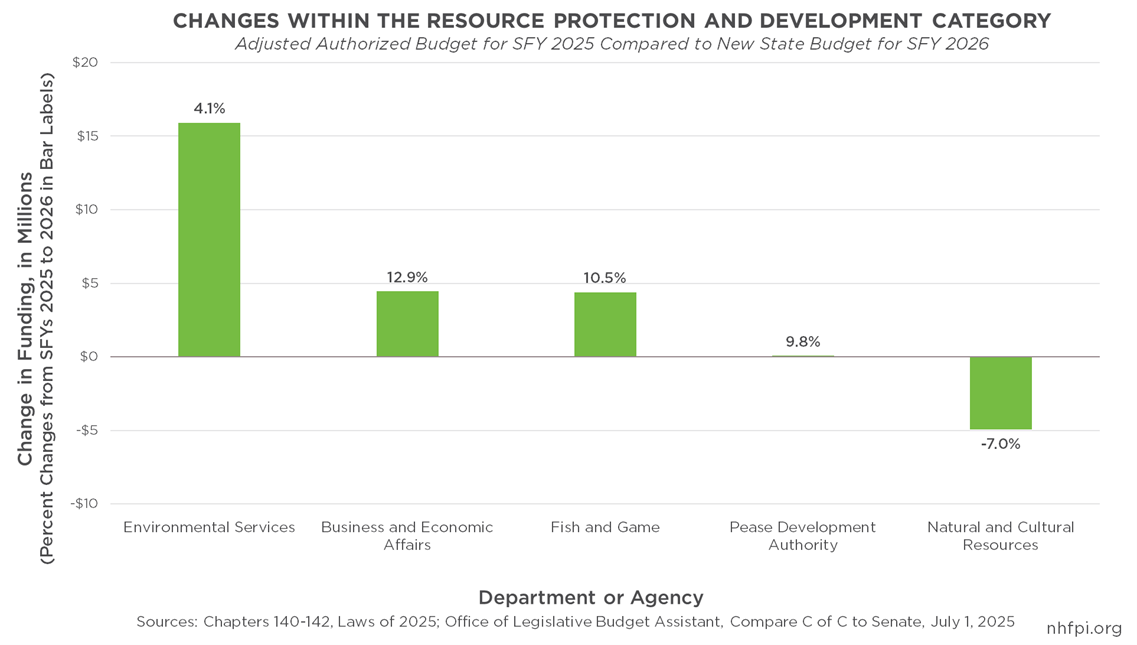

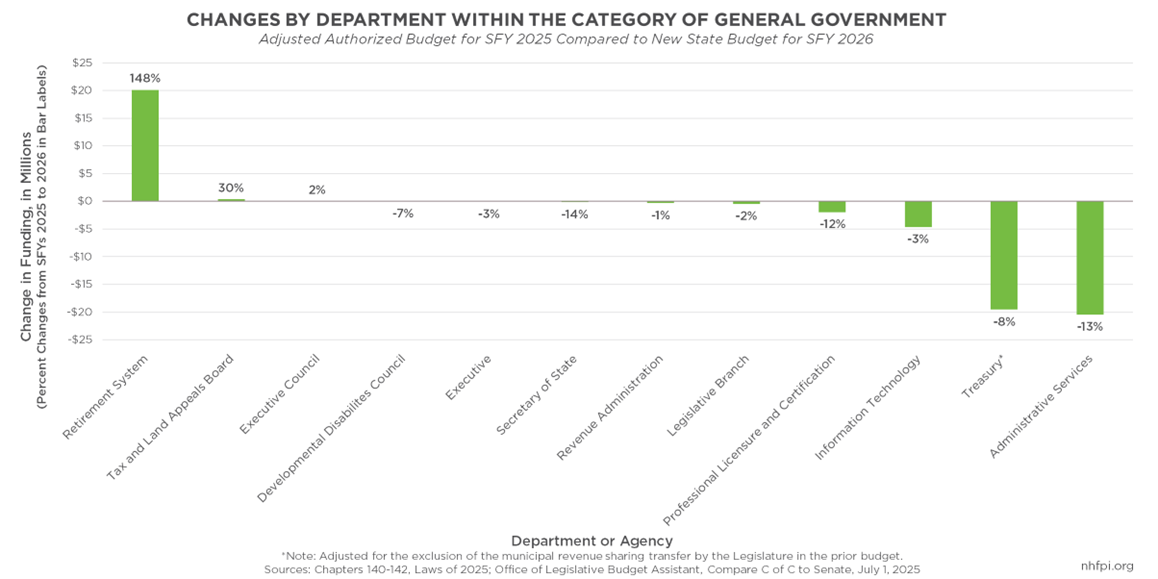

However, the largest percentage increase was in the Resource Protection and Development category ($124.5 million, 14.3 percent), which was boosted by appropriations for water infrastructure from a separate trust fund that flows through the new State Budget. The Justice and Public Protection category, including appropriations for settlements in Youth Development Center-related cases, grew by $106.2 million (6.2 percent). Both Education ($61.8 million, 1.8 percent) and Transportation ($26.5 million, 1.7 percent) had relatively limited rates of growth in the new budget, unadjusted for inflation. General Government appropriations declined by $29.4 million (3.1 percent).

To support these services, the State Budget expected about a third of State expenditures to be funded with federal transfers in the SFYs 2026-2027 biennium. State General Fund appropriations, which is the most flexible set of dollars policymakers have access to, totaled about $3.85 billion over the biennium or about 24.3 percent of the total State Budget. These figures are a reduction from the $4.27 billion and 28.1 percent expected by the prior State Budget’s plan. This decrease in General Funds reflects the relatively constrained tax revenues in this budget cycle and the extent to which the new State Budget draws on other funds to support its operations. The Education Trust Fund, which holds the revenues used for aid to local public schools and for several other purposes, would grow in dollar terms from the last State Budget, rising from $2.50 billion to $2.61 billion in appropriations, but decline slightly as a percentage of the total budget from 16.5 percent of the last State Budget to 16.4 percent in the new one.

Subsequent sections of this Report examine the details of the changes in each expenditure category.

Health and Social Services

The Health and Social Services category of the State Budget is comprised almost entirely of the State’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The DHHS is responsible for several vital programs, including Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program (NHCCSP), child protection, public health services, and many others.

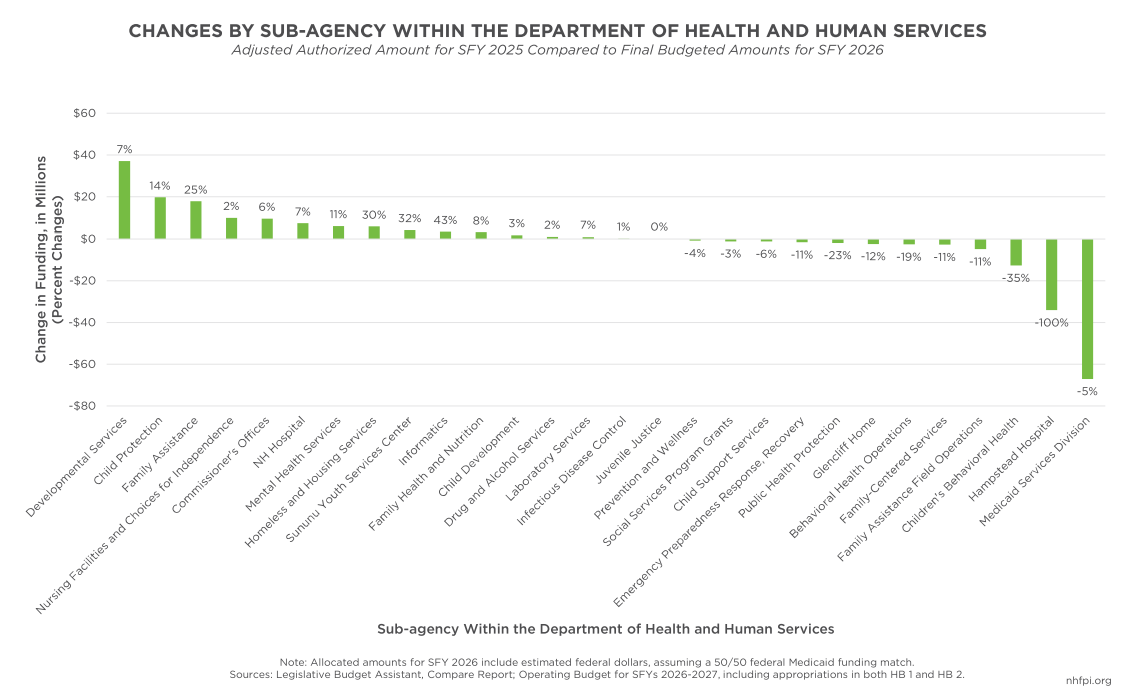

The new State Budget allocates a total of $7.1 billion for the DHHS across the biennium, which is an increase of 7.6 percent from the $6.6 billion allocated in the prior SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget, as enacted June 2023, excluding the allocation of State employee pay increases. Using the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized budget as a baseline, which includes State employee pay increases, Medicaid reimbursement rate increases, and other changes made to the agency’s budget since June 2023, appropriated funding declined by about $32.0 million (0.9 percent) in SFY 2026 before increasing by $85.9 million (2.4 percent) between SFYs 2026 and 2027. While the overall biennial DHHS Budget would increase under the new State Budget, unadjusted for inflation, 12 of the 28 sub-agencies, or activity units, within the DHHS would experience funding declines between the current Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026.

Outside of the DHHS, the State Veterans’ Home comprises the rest of the State Budget under the category of Health and Social Services. Under the new State Budget, the Veterans’ Home would receive about $103.4 million across the biennium, an increase of $18.0 million (21.0 percent) from the $85.4 million allocated in the prior State Budget, unadjusted for inflation or for the changes in State employee salaries in the previous budget.

Medicaid Funding Changes

When comparing the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 with the new State Budget’s amount for SFY 2026, the State’s Division of Medicaid Services experiences a decline of approximately $67.1 million (4.8 percent). Declines in the Medicaid budget are primarily due to changes to uncompensated care payments for hospitals, resulting from a newly established agreement formed between hospitals and the State during the State Budget process. These uncompensated care payments, also formally known as Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments, are funded by the Medicaid Enhancement Tax (MET), which is paid by hospitals and matched with federal Medicaid funds. DSH payments are allocated to hospitals that provide health care services for Granite Staters who are uninsured or receive coverage through Medicaid, which typically has lower reimbursement rates than private insurance or Medicare.[ix]

Under the new State Budget, budgeted allocations to the uncompensated care pool will decline by $408.9 million (90.2 percent) between the SFYs 2024-2025 biennium ($453.3 million) and the budgeted amount for SFYs 2026-2027 ($44.5 million). While there is a reduction in official budget lines, policymakers have identified that the new agreement reflects language in a separate piece of legislation outside of the State Budget, Senate Bill 249 introduced during the 2025 legislative session, with hospitals expected to receive back the same amount in aggregate as the prior agreement.[x] Although the details of this new agreement between hospitals and the State were not made public in text as part of the budget process, this language suggests that DSH payments across the next biennium will be funded with other resources outside of the State Budget.

The budget lines for the State’s contracts with Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) see an increase of about $141.1 million (16.9 percent) between the current SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized appropriation and the new State Budget’s SFY 2026 appropriation of $973.6 million. Despite increases during the first year of the biennium, the new State Budget postpones June 2027 Medicaid payments to MCOs until the beginning of SFY 2028, effectively shifting the disbursement of funds until the next biennium. While this adjustment is not expected to impact service delivery, it will delay the timing of payments outside the current budget cycle and assumes greater availability of funds during the next biennium. This provision will save $25.0 million in General Funds during SFY 2027, in addition to likely equivalent federal Medicaid matching dollars, impacting MCO payments for the Granite Advantage Program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and standard Medicaid.

Allocations towards the Adult Dental Program decline by $4.5 million (38.3 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 ($11.7 million) and the final budgeted amount for SFY 2026 ($7.2 million). The budgeted amounts for both SFYs of the 2026-2027 biennium are also lower than the SFY 2024 actual amount spent, which was reported as $11.7 million. While proposed funding will decline, the budgeted amount is in alignment with the agency’s requested amount submitted; enrollment in the program is expected to remain relatively flat, and the annual cost per beneficiary is projected to decline, from $3,041 in SFY 2025 to $1,876 in SFY 2026.[xi] In addition to funding declines, the new State Budget also establishes a research study to determine cost-effectiveness of the Adult Dental Program, with the DHHS required to submit a report of findings to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee by January 1, 2027.

The final State Budget adds three staff positions for Medicaid Recoveries, bringing in a net General Fund savings of approximately $271,000 in SFY 2026 and $534,000 in SFY 2027, after accounting for additional estimated recoveries resulting from the increased staff.

Another $3.8 million is also allocated to the DHHS’ Division of Economic Stability to support a tier-one call center to process Medicaid eligibility determinations.

In addition to funding adjustments, the new State Budget includes several policy changes impacting the state’s Division of Medicaid Services, as well as Medicaid providers and enrollees across New Hampshire. These include:

- The resubmission of a federal Medicaid waiver to establish work requirements already outlined in statute and require Granite Advantage adults to work or participate in an eligible community engagement activity at least 100 hours per month, which is more than the 80 hours per month included in the final federal reconciliation bill;[xii]

- The requirement of the DHHS to annually set cost-reflective rate parity for Medicaid managed care services, and an allocation of $2.3 million in SFY 2027 to establish those payment rates;

- Return to pre-COVID-19 pandemic regular eligibility redeterminations for Medicaid enrollees renewing their coverage, and allowing the expiration of temporary Section 1902e(14)(A) waivers approved by the federal government during the COVID-19 Medicaid continuous enrollment provision;[xiii]

- Policy changes around preferred pharmaceutical drugs for Medicaid beneficiaries from generics-first to the lowest-cost drug regardless of type, saving an estimated $3.9 million in General Funds across the biennium;

- Establishment of an incentive program among MCOs to encourage Medicaid recipients to seek the lowest cost outpatient procedure care when clinically appropriate, with the DHHS required to establish an implementation plan within 120 days of the budget’s passage;

- Termination of the Medicaid to Schools Program if current parental consent policies are ever changed at the federal, state, or local level; and

- Accelerated implementation of the at-home dialysis program for Medicaid recipients, saving an estimated $50,000 in General Funds during SFY 2027.

Premiums and Copayments for Medicaid Enrollees

Under the new State Budget, New Hampshire will seek a federal Medicaid waiver to establish premiums among Granite Advantage adults with incomes at or above 100 percent of the federal poverty guideline, which is $15,650 for a household of one in 2025.[xiv] Enrollees will be required to pay a monthly premium for coverage depending on household size, which will range from $60 for a household of one up to $100 for a household of four or more. According to DHHS testimony during a House Finance Committee work session, approximately 11,000 adults in the Granite Advantage program will be required to pay these premiums.

Households with children enrolled in the CHIP component of New Hampshire’s Medicaid program will also be required to pay a premium if they earn at or above 255 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $53,933 for a household of two in 2025.[xv] Similarly to premiums for Granite Advantage adults, monthly CHIP premiums will depend on household size, ranging from $190 for a household of two up to $270 for a household of four or more. In alignment with federal law regarding cost sharing for Medicaid beneficiaries, both Granite Advantage and CHIP premiums cannot exceed five percent of a household’s income.[xvi]

While the new State Budget will not require premiums for other populations enrolled in Medicaid, the Budget increases prescription drug copayments on preferred drugs from the current $1-2 up to $4 for beneficiaries, subject to any federal limitations and regulations. According to the DHHS, Granite Advantage and CHIP enrollees paying premiums will be excluded from these higher prescription drug cost shares.

The addition of cost shares for individuals enrolled in Granite Advantage will contribute an estimated $5.0 million in cost savings towards the Granite Advantage Healthcare Trust Fund for SFY 2027 alone, the first year of their planned implementation. Revenue collected from premiums for CHIP enrollees will supply $3.3 million in SFY 2026 and $11.0 million in SFY 2027, according to projections, as policymakers expected implementation starting in January 2026. Increased prescription drug copayments will add $750,000 in revenue for each year of the biennium and reduce the Medicaid federal match by an equivalent amount.[xvii] Cost savings from both CHIP premiums and higher pharmacy cost shares are factored into the General Fund portion of the Medicaid Budget, suggesting that revenue will not be held in a separate fund and, in turn, could be used to fund operations outside of DHHS. According to testimony from the DHHS, projected savings from premium revenue do not factor in additional administrative costs that may occur when establishing and implementing these cost shares.

State Medicaid Plan amendments are required to be processed on or before January 1, 2026 for both CHIP premiums and higher prescription drug cost shares, and on or before July 1, 2026 for Granite Advantage premiums. These amendments will likely include more information regarding how premiums will be collected, the procedures for when Medicaid enrollees are unable to pay cost shares, and other necessary details for implementing these structures during the biennium that were not included in the State Budget’s text.

Developmental and Acquired Brain Disorder Services

Within the DHHS’s Division of Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS), the Bureau of Developmental Services contracts with providers to supply services for Medicaid enrollees with developmental disabilities or acquired brain disorders. Among traditional budget lines for these services, the final State Budget allocates $9.3 million (2.1 percent) less for developmental services in SFY 2026 compared to the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025. Acquired brain disorder services also experience a decline of $21.4 million (37.9 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026.

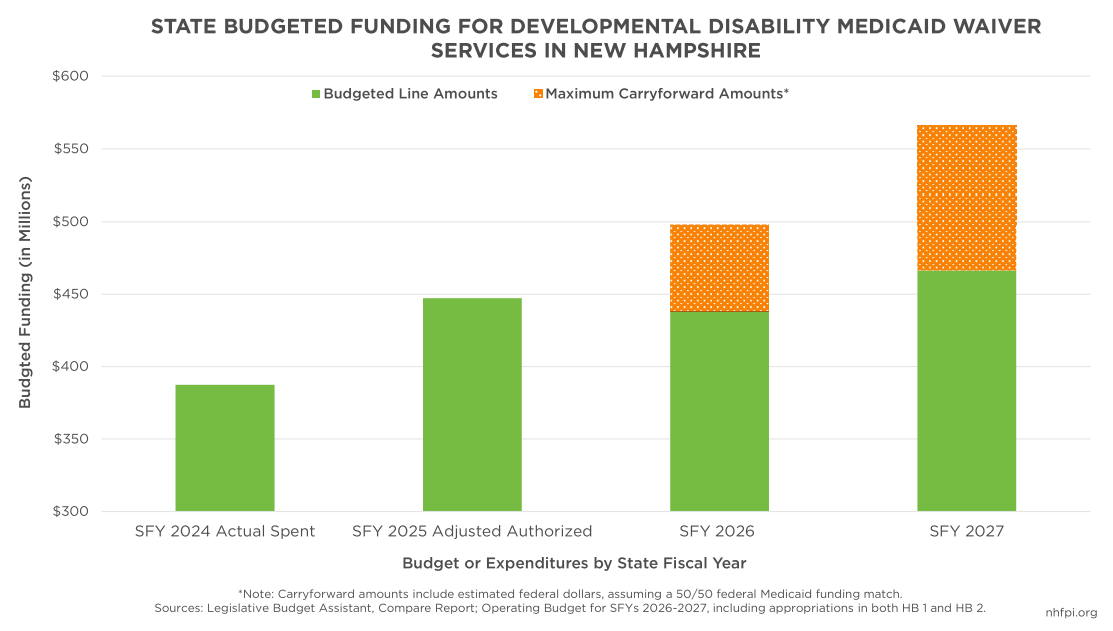

While fewer dollars are allocated in each budget line, the DHHS is authorized to use up to $30.0 million in funds for SFY 2026 and up to $50.0 million for SFY 2027, with likely equal amounts in federal Medicaid match dollars, carried forward from prior years’ unused funds. These additional funds will draw on available amounts in the Developmental Services Fund, the Acquired Brain Disorder Services Fund, and the In-Home Support Waiver Fund. The Division’s budgeted lines for developmental services increase in the second year of the biennium, with the budgeted amount for SFY 2027 ($466.3 million) higher than both the authorized amount for SFY 2025 ($447.3 million) and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026 ($438.0 million), even before the transfers from the carry-forward funds.

In addition to the carryforward of funds, the new State Budget also includes unique language allowing the Division of LTSS to request additional funding through the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee if expenditure needs exceed the allocated amounts. Increased allocations could help ensure there continues to be no waitlist for developmental disability services, including for children aging out of school-based services, people moving into New Hampshire requiring supports, and anyone currently receiving services that may require enhanced or additional aid during the biennium.

Within the Division of LTSS, the new State Budget also allows for the carryforward of $10.0 million in unspent funds from SFY 2025 to support additional funding for community-based residential services for people with disabilities. This allocation was included in the DHHS’ agency budget request following the establishment of a Room and Board payment calculation in SFY 2024 to help ensure full funding for residential services.[xviii]

The final State Budget also includes language allowing funds for the developmental disability pilot program to lapse on June 30, 2025, which was reportedly an estimated $2.0 million out of an original $2.8 million appropriation from 2022; to help fill the gap resulting from lapsed funding, the State Budget allocates $1.0 million towards the pilot program for the upcoming biennium.

Older Adults and Adults with Physical Disabilities

The Division of LTSS budget includes appropriations for both nursing home Medicaid reimbursements as well as the Choices for Independence (CFI) Medicaid Waiver program, providing home- and community-based supports for older adults and adults with physical disabilities.

Medicaid funding directly provided to the State’s nursing facilities will increase by $125.5 million (24.9 percent) between the SFYs 2024-2025 biennium and the budgeted amount for SFYs 2026-2027, which totals $629.1 million. Nursing facilities will also have an aggregate increase in funding resulting from the Nursing Facility Quality Assessment, a tax on nursing facilities that is then matched with federal Medicaid funds and paid in assistance to nursing facilities through Medicaid Quality Incentive Payments; these funds would rise $18.9 million (11.1 percent) between the SFYs 2024-2025 biennium the allocated amount for SFYs 2026-2027 ($190.0 million). ProShare payments to county nursing facilities will experience a decline, decreasing by $14.3 million (11.5 percent) between the prior biennium and the new State Budget, with ProShare payments also anticipated to be funded entirely with federal funds.[xix]

While nursing facilities will experience an aggregate increase in the State Budget across the three budget lines that appropriate resources to nursing facilities, Medicaid funding available for the CFI program will increase by a smaller amount.[xx] Under the new State Budget, funding for the CFI program will increase by $23.9 million (10.1 percent) between the SFYs 2024-2025 budgeted amount ($235.9 million) and the budgeted amount for SFYs 2026-2027 ($259.7 million). Despite increases in budgeted amounts across the two biennia, the amounts allocated for both SFY 2026 ($125.1 million) and SFY 2027 ($134.6 million) are lower than the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 ($141.6 million).

In addition to allocations for nursing facilities and the CFI program, the new State Budget made several smaller investments to support older adults and people with disabilities in New Hampshire. These include:

- $3.0 million to support faster turnarounds for the backlog of Medicaid long-term care eligibility determinations, funded with temporarily increased annual nursing facility licensing fees for the upcoming biennium only;

- $700,000 to fund congregate housing under the Medicaid waiver program;

- $550,000 to establish 50 guardianship slots for individuals released from hospital settings who are legally incapacitated and require help making decisions around hospital discharge;

- $211,718 to institute two percent rate increases each year of the upcoming biennium to support Medicaid-funded intermediate care for children with disabilities; and

- $200,000 to increase funding for the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) caregiver grant program.

Counties are required to contribute a large portion of the non-federal Medicaid dollars used to provide long-term support for their residents, including older adults and adults with physical disabilities. State law requires that year-over-year growth in the county share of costs is limited to two percent annually. Under the new State Budget, the county cap will be raised to three percent for the SFYs 2026-2027 biennium only. With this change, counties will be required to contribute more funds towards the total cost of care, boosting the cap up to a statewide maximum of $135.8 million in SFY 2026 and $139.9 million in SFY 2027. This year-over-year increase follows the stagnation of county contributions in the prior State Budget, with counties required to contribute equal amounts in SFYs 2024 and 2025 ($131.8 million) and thus effectively not experiencing the two percent growth rate last biennium.

While the county cap will increase, under the new State Budget, counties will receive compensation for overpayments towards their share of Medicaid costs in SFYs 2020-2021. Approximately $5.6 million will be allocated annually among the counties for SFYs 2026-2029, equating to nearly $11.3 million across the new biennium. While the increasing caps would typically put more fiscal pressure on counties, these reimbursements will be larger than contribution increases and may help offset cost constraints during this biennium.

Lastly, the State Budget established a committee to study the potential integration of Medicaid-funded long-term care into the managed care system, with a report required to be submitted by the committee by October 1, 2025.

State Commission on Aging

The State Commission on Aging, established in 2019, exists to advise the Governor and the Legislature about policy and planning related to aging, and is attached to the Department of Administrative Services.[xxi]

In the new State Budget, the State Commission on Aging’s appropriations will shift from an SFY 2025 appropriation of $232,436 in budget line items to a flexible fund of $150,000 per year, which would support compensation for the Executive Director and the Commission’s activities.

The State Commission on Aging will have its terms for membership extended from two years to three years under the new State Budget. The Commission will also have an attached advisory council focused on the system of care for healthy aging in the state that will meet at least quarterly and make recommendations regarding the system of care.

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services

Under the new State Budget, the Bureau of Mental Health Services will experience an increase of approximately $6.0 million (11.2 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the proposed amount for SFY 2026. This rise is almost entirely due to an increase in General Fund allocations for uncompensated care at community mental health centers in the state, with an additional $5.0 million allocated in SFY 2027 for the same purpose.

The Bureau for Children’s Behavioral Health will experience a decline of around $12.7 million (35.2 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026. Approximately $9 million of this total decline was due to a reorganization of funds into Medicaid Services and the Division of Children, Youth, and Families, rather than a change in available services for youth. However, the Children’s Behavioral Health Resource Center (CBHRC) was not funded under the new State Budget, contributing to around $1 million of this total decline; the State’s CBHRC provided youth and families with wraparound services for locating providers, acquiring needed information, and other case management support.[xxii] Allocations for the Choose Love program are also reduced by $100,000 between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026, although allocations remain higher than the SFY 2024 actual spent amount.

Funding for the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services remained relatively flat between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026, increasing by $1.0 million (1.9 percent) between the two fiscal years. Funding appropriated to the Bureau includes an added $1.0 million across the biennium to support the Recovery Friendly Workplace Initiative, as well as an extension of prior funds for the Initiative that were scheduled to lapse on June 30, 2025. The new State Budget also changes the name of the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund to the Addiction, Treatment, and Prevention Fund; this change would provide more flexibility for the Fund to accept and use Opioid Abatement Funds, a more restricted form of revenue, in the future.

New Hampshire Hospital, which provides inpatient mental health treatment to residents with severe and persistent mental health concerns, will experience an appropriation increase of approximately $7.3 million (6.6 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budget amount for SFY 2026.

Hampstead Hospital, another facility providing inpatient mental health care, was removed from the State Budget following its recent approved lease, and operational oversight change, to Dartmouth Health.[xxiii] The Hospital had been under the DHHS’s operation since 2022, when the State purchased the facility with flexible federal funds to provide inpatient mental health treatment in an effort to bring down long wait times for care, particularly for children. The lease of Hampstead Hospital, and shifting the costs of operations off of the State Budget, equates to a decline of around $58.1 million between the amount appropriated during the prior State Budget for SFYs 2024-2025 and the new State Budget biennium.

The new State Budget calls for the sale of several State-owned properties used or formerly used to house individuals experiencing mental health challenges or housing instability. The proposed sale of the Philbrook Center will bring in an estimated $5.0 million in SFY 2027, with the Center currently being used as transitional housing for 16 people who were formerly receiving services at New Hampshire Hospital; the DHHS would be required to develop a transition plan for people currently receiving services at the Center ahead of the sale. The Tirrell House, which is currently used as a shelter for people experiencing homelessness in Manchester, will be sold for an estimated $300,000 in SFY 2026. Finally, unoccupied State-owned property at Hampstead Hospital will be sold, although no estimated savings were formally identified in the State Budget; portions or the property that will be used as a replacement facility for the Sununu Youth Services Center (SYSC) will not be included in the sale. All three properties will be first offered to the city or town in which they reside, then to each corresponding county government, before being placed on the open sale market by January 1, 2026.

Public Health Services

The new State Budget reduces funding to the Family Planning program, which provides low- to no-cost preventive and reproductive health care to approximately 2,500 people annually at health centers across the state. Budgeted allocations to the program are reduced by about $272,794 (15.4 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 ($1.8 million) and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026 ($1.5 million), although appropriation levels are higher than the SFY 2024 actual spend ($1.1 million). The new State Budget also includes unique language setting aside $75,000 in each year of the biennium specifically for family planning services provided at Coos County Family Health Services.

The new State Budget makes two key changes for the State Loan Repayment Program (SLRP), which helps to recruit and retain health professionals to commit to working in rural or medically underserved areas in New Hampshire. First, the budget allows new participants to enter into the program during the upcoming biennium only if General Funds are not used to support new applicants. Through testimony to the Senate Finance Committee, the DHHS identified additional federal funding available to support the SLRP, with the budget likely allowing for the use of those funds. Second, the final State Budget also appropriates $500,000 across the biennium to support a newly established Family Medicine Residency Program to recruit and train family physicians in the state’s North Country.

All General Funds for the Tobacco Prevention and Cessation program were eliminated under the new State Budget, with only $1 allocated each year of the biennium to keep the program in statute in the event that funds are available in the future. According to DHHS testimony, General Funds for the program supported a contract for the promotion of the state’s Quitline, providing services for both adults and youth seeking to reduce nicotine use. About $2.3 million in federal funds are allocated for the program across the new biennium; however, those funds are not likely to be available in the future due to potential federal changes.

The final State Budget also allocates available federal funds to help partially offset about $81.3 million in COVID-19 pandemic-related funding that was abruptly terminated by the federal government in March 2025.[xxiv] The total allocation of $1.9 million across the biennium will support various permanent and temporary positions within the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) Program, the immunization program, and other public health infrastructure.

Lastly, the new State Budget eliminates requirements for children to be vaccinated against Hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccinations after June 2026, and it repeals certain State rulemaking authority related to requiring vaccinations.

Sununu Youth Services Center

Under the new State Budget, the SYSC received an increase of approximately $4.1 million (32.3 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the proposed amount for SFY 2026. The majority of increased funds are allocated for overtime pay for employees, which total more than $3.0 million in actual spending in SFY 2024 while only having $500,000 originally budgeted for that year, as well as contracts for operational services at the SYSC.

The budget also calls for the sale of the SYSC during the new biennium, with a potential estimated $80.0 million of sale revenue to be deposited into the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund in SFY 2027. The Legislature has made several efforts to close the SYSC entirely, including in the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget, as the number of individuals served by Center has been a substantially smaller number than the facility’s capacity in recent years.[xxv]

While no new funds were allocated, the new budget also allows for the use of General Funds to support the construction of the new SYSC replacement facility, as long as appropriations are approved by the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. Under prior law, only federal funds could be used for that purpose.

Youth and Family Services

The new State Budget reduces funding for youth residential placements by a total of 10.0 percent across all budget lines, impacting both the Division for Behavioral Health and the Division for Children, Youth, and Families. While funding would be reduced, $5 million allocated to placements was shifted from SFY 2027 to SFY 2026 to support a larger anticipated need during that fiscal year. The new budget does allow the DHHS to request additional money through the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee in the event that spending exceeds budgeted amounts.

The final State Budget will also reduce funding for the Office of the Child Advocate by approximately $357,000 (32.3 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026. As a result of these funding reductions, four positions would be eliminated within the Office. Language was added that would affect the functioning of the Office, including:

- Language clarifying that there should be non-partisanship in oversight duties;

- A nomination process that involves a nomination by the Governor and approval by the Executive Council, rather than a gubernatorial appointment without Council approval;

- Requiring approval for out-of-state travel by the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee, except travel that is required to ensure children are receiving appropriate services; and

- Limiting the Office’s access to children’s files for investigations to include only those involved with the State’s Division of Children, Youth and Families or who are in residential treatment facilities in the state.

Maternal Health and Adverse Childhood Experiences Initiative

The State Budget included language from a separate bill, which was also known as “Momnibus 2.0” as it followed an earlier piece of multifaceted legislation related to maternal health. This policy language was designed to help address needs resulting from the closure of labor and delivery units across the state and create perinatal mental health supports for Granite State women. This collection of maternal health policies includes allocations of $150,000 for rural maternal health Emergency Medical Services training and $30,000 to support a study on reducing barriers and examining sustainability for independent birth centers during the biennium. Additionally, insurance companies would be able to waive copays for mental health and substance use treatment for perinatal patients. The perinatal care and supports portion of this package also requires:

- Depression screens during well-child visits for pregnant or postpartum patients to be covered by private insurance and Medicaid

- Home visiting services during pregnancy and up to 12 months postpartum to be covered by commercial insurance plans

- The creation of a perinatal psychiatric provider consult line in statute starting SFY 2028, with a $275,000 appropriation that year

- DHHS to examine the development of a perinatal peer support certification program

- Employee protection for unpaid time off to attend up to 25 hours of postpartum care and pediatric appointments during the infant’s first year of life for employers with 20 or more employees

The State Budget also includes language for an Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Prevention and Treatment Program. ACEs can include physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, neglect, witnessing violence, or experiencing homelessness, food insecurity, and household instability.[xxvi] Over the biennium $300,000 will be allocated to support children ages birth through age six who have experienced ACEs or other “severe emotional disturbances” through:

- Increases in Medicaid reimbursement for early childhood mental health care

- Increased salary levels or reimbursement rates for individuals with an early childhood and family mental health credential

- Funding for training and professional development in early childhood mental health care

- Creation of a five-year plan by DHHS to increase state workforce capacity for child-parent psychotherapy supports

Other Health-Related Services

The new State Budget includes two key changes around services for Granite Staters experiencing food insecurity, including a $30,000 allocation towards the WIC Farmer’s Market Nutrition Program, as well as $105,000 to support two positions to administer the newly established Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) Program.

The budget also repeals the Prescription Drug Affordability Board (PDAB) in its entirety. The PDAB was formed in 2020 to help find prescription cost savings for public payers, while also ensuring that providers can still access the prescriptions they need to treat their patients. While it has been eliminated, the State Budget retains $2.5 million in generated revenue from prescription drug cost savings in SFY 2027, resulting from recommendations given by the PDAB.

Lastly, the new State Budget also changes the name of the Office of Health Equity to the Office of Health Access, and keeps a hiring freeze in place for the Office throughout the biennium, even if the Governor’s current hiring freeze is lifted. According to information provided during the House phase of the budget process, this would impact four positions within the Office that are currently vacant.

Early Care and Education

Overall expenditures for DHHS’s Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration (BCDHSC) increased by approximately $1.2 million (2.1 percent) for SFY 2026 compared to SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized amount. This Bureau includes most early care and education (ECE) funding and administrative supports, and it also distributes funds for New Hampshire’s Child Care Scholarship Program (NHCCSP), a state-federal partnership that provides child care assistance to families with low and moderate incomes.

The new State Budget includes language that would appropriate $7.5 million in federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) reserve funds each fiscal year to the Child Care Workforce Grants if permitted by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; however, based on information from NH DHHS, in consultation with the U.S. DHHS, grants to child care providers for the purpose of supporting the recruitment and retention of the ECE workforce is not an allowable use of TANF reserve funds.[xxvii] As such, the $7.5 million allocation each fiscal year to the Child Care Workforce Grants in the SFY 2026-2027 budget will likely not be able to be allocated. Without the inclusion of the Child Care Workforce Grants, funding to the BCDHSC decreases in SFY 2026 compared to the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized amount by approximately $6.3 million (10.9 percent).

The largest share of BCDHSC funding is proposed for the Child Development Program, the funding mechanism for the NHCCSP. The SFY 2026 amount ($44.8 million) is over $10 million more than the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and reflects an increase of more than $10 million in the “Employment Related Child Care” line, which funds the NHCCSP. There were, however, reductions of $3.5 million in “Protect & Prevent Child Care” funds that will be relocated to the Division of Children and Families and a new $3 million allocation added to “contracts for program services.” The substantial increase in funding for the NHCCSP likely reflects a projected rise in the number of children qualifying for and using NHCCSP. As a result of the eligibility expansion, between in January 2024 and April 2025, NHCCSP utilization increased by over 65 percent, from 2,660 children in December 2023 to 4,401 children in April 2025.[xxviii]

The average cost per child enrolled in the NHCCSP in SFY 2024 was $9,502.[xxix] Over 55,000 children under 13 years old may be eligible for the NHCCSP, or approximately 32 percent of all children under 13 in New Hampshire in 2023, the most recently available data from the U.S. Census Bureau.[xxx] If all eligible children were utilizing funds from NHCCSP at the 2024 average cost per child rate, the annual cost for the program would be over $522.6 million.

Education

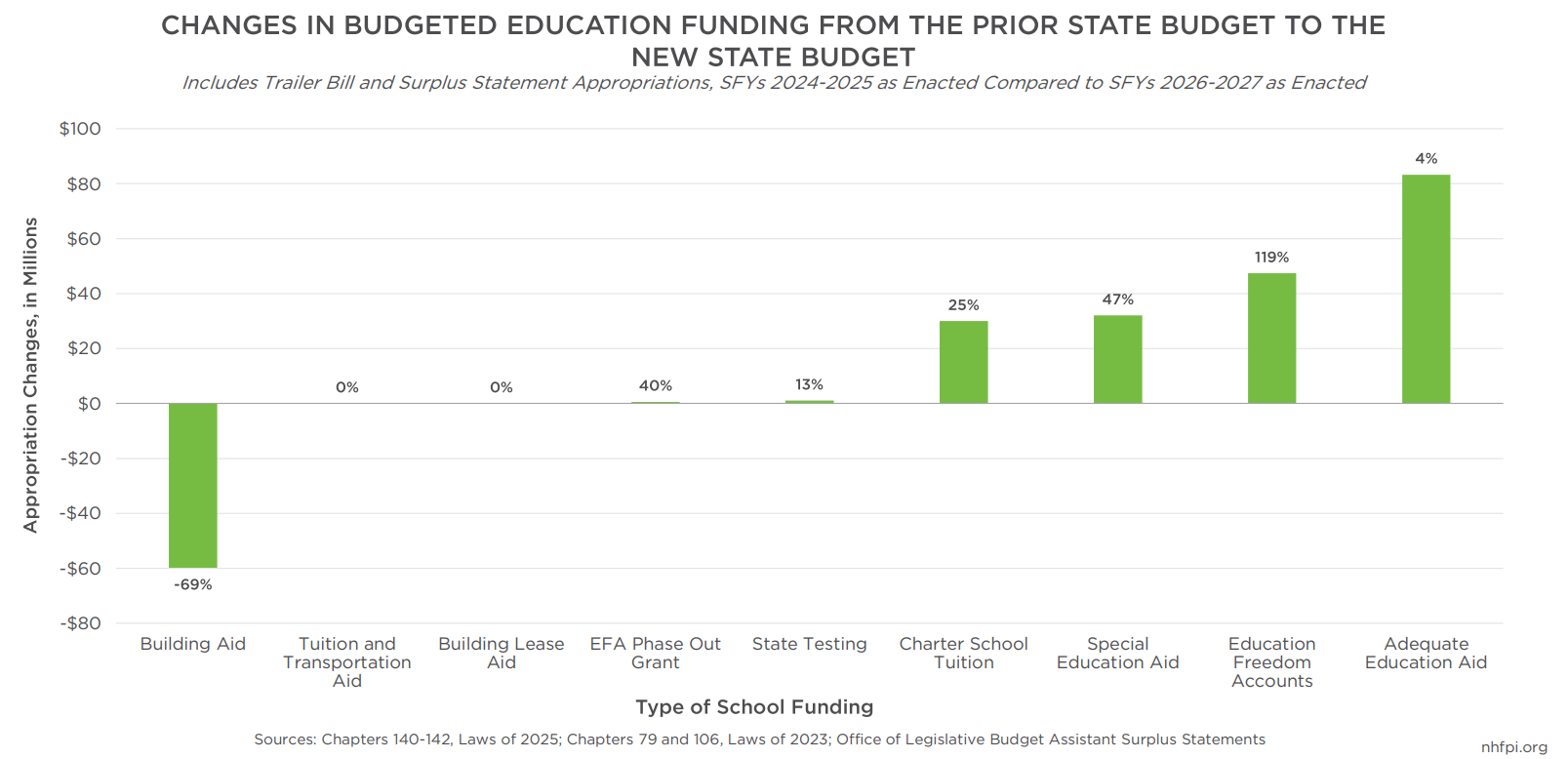

The State Budget includes modest increases for both K-12 education and the Community College System of New Hampshire (CCSNH), but a substantial decrease for the University System of New Hampshire (USNH), relative to the SFYs 2024-2025 budget. Changes in K-12 education funding reflect increases in Adequate Education Aid to local public schools, Special Education Aid, Education Freedom Account funding, and charter school tuition payments.

Adequate Education Aid

The primary mechanism through which State funding is supplied to local public schools for supporting education is Adequate Education Aid. Most of this assistance comes in the form of per pupil Adequate Education Grants, will include base grants of $4,351 per full time student in SFY 2027 (academic year 2026-2027), under current law, with additional per pupil funding for students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, students receiving special education assistance, and English language learners. These differential payments will follow current policy, as established in the new State Budget, and be rounded up to the nearest dollar. [xxxi] Additional funding for students who do not meet third grade reading proficiency scores was eliminated as part of changes in the SFYs 2024-25 State Budget.

In SFY 2025, the Adequate Education Aid funding formula distributed an average of $5,279.81 for each public school student in New Hampshire.[xxxii] This figure includes the base adequacy amount as well as differentiated aid for students qualifying for free or reduced priced meals, special education, and as English language learners. A December 2020 report from the legislatively-established Commission to Study School Funding identified that, “[o]n average, New Hampshire provides approximately $5,900 per student from state funding sources, or about 32 percent of total spending per student.”[xxxiii] In the 2023-2024 school year, New Hampshire local public school districts reported average operating expenses of $21,545.17 per pupil, with added costs of tuition, transportation, facility purchase or construction, capital costs, and interest bringing the total average per student cost to $26,320.12.[xxxiv] The difference between resources provided by the State and average school district costs per pupil is largely bridged by funding from local property taxes.[xxxv] Property taxes raised and retained locally accounted for 70 percent of all reported school district revenue in the 2023-2024 school year.[xxxvi]

On July 1, 2025, after the State Budget process was completed, the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Contoocook Valley School District, which had sued the state for failing to meet its constitutional obligation to provide sufficient funding to give New Hampshire students the opportunity for a constitutionally adequate public education.[xxxvii] The NH Supreme Court, however, did not uphold a lower court’s ruling that adequacy aid should be immediately $7,356.01 per student, but stated that the figure determined by the Superior Court was a conservative minimum threshold. The NH Supreme Court went on to note, “It is now incumbent upon the legislative and executive branches to remedy the constitutional deficiency that we have identified.”

The final budget increases Adequate Education Aid by approximately $83.3 million across the biennium. This figure likely reflects an estimate of changes in public school enrollment, and the anticipated need of enrolled students, to meet the required 2 percent annual increase that went into effect at the start of SFY 2024.

Outside of Adequate Education Aid, the new State Budget appropriates $3.0 million from the Education Trust Fund to support learning platforms to provide instructional materials across all content areas for K-12 students.

Special Education Aid

Special Education Aid is separate from the differentiated special education funding provided through the Adequate Education Aid funding formula, and is based on the number of students with Individualized Education Plans. Special Education Aid funding is in addition to the adequacy formula aid and is intended to help schools pay for the education of students who have significant special education costs beyond the average cost per pupil.

Special Education Aid is allocated to schools based on students with special education costs that exceed 3.5 times the estimated State average cost per pupil based on the preceding school year. The school district is responsible for all costs below 3.5 times the average amount, but the State will pay 80 percent of the costs between 3.5 times and ten times the state average per-pupil expenditure. If the cost rises above ten times the amount, the State pays the entire cost beyond that threshold.

Another type of related assistance outside the Adequate Education Aid formula was added as part of the SFYs 2024-2025 budget cycle and addresses the costs for educating students who require an “episode of treatment,” which is defined in statute as “when a child needs to be placed by the [DHHS] in a DHHS-contracted and/or certified program to receive more intensive treatment and supports and has the objective of helping children in crisis avoid or reduce the use of psychiatric hospitals or emergency rooms.”[xxxviii] Special education costs related to an episode of treatment and the determination of placements by New Hampshire DHHS are to be covered in full by the State under the law.[xxxix] The current budget will draw funding for this purpose from the Education Trust Fund.

The new State Budget appropriates $99.8 million to Special Education Aid, of which any unused funds will roll forward into the next State Budget and be transferred to court ordered placements in accordance with RSA 186-C: 18, III. The new State Budget also eliminates the provision that prorates all Special Education Aid funding to school districts based on available budgeted funds, and instead guarantees at 80 percent of the amount the school district is entitled to, prorating only between 80 percent and 100 percent of funding that would be appropriated if the State Budget’s funding threshold had not been reached.

Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid

The new State Budget reinstates a form of Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid, which had been established in prior iterations of the State’s Adequate Education Aid funding formula. This aid will be allocated to municipalities that have relatively low taxable property values per student and would total up to $1,250 per student. There would be a sliding scale reduction for this aid that disappears for municipalities with more than $1.6 million in taxable property value per pupil. This aid would be in addition to funding through Extraordinary Needs Grants, which are provided by the State based on community-level characteristics, rather than those of individual students. These funds are calculated using the amount of taxable property value in a community per student eligible for free and reduced price meals, adding a maximum of $11,500 per eligible student with a sliding scale reduction as taxable community property value increases.[xl]

However, these two forms of targeted aid would be capped for the largest communities in the state. In municipalities with more than 5,000 resident students, the total amount of Extraordinary Needs Grants and Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid combined would be limited to $3,750 per student. Currently, only the cities of Nashua and Manchester exceed 5,000 resident students, and only Manchester is projected to be impacted, with an expected reduction of about $10 million in SFY 2028. Policymakers considered implementing this reduction during SFY 2027; however, an amendment to a separate bill modified the State Budget Trailer Bill and delayed the implementation of this reduction by a year, into the next State Budget cycle, to give the City of Manchester and the Manchester School District time to prepare for the reduction in their school budget.

SFY 2026 Adequate Education Aid estimates project that districts will also receive funding at a rate of 0.15 of full-time student aid for each course credit taken by a local community student who is home schooled. Hold Harmless Grants, first instituted in SFY 2024 to ensure school districts did not receive less funding after the funding formula changes that year, will be reduced to 80 percent of their original value in SFY 2026, a pre-existing law that was not altered by the new State Budget.[xli]

Education Freedom Accounts

Education Freedom Accounts (EFAs), enacted as part of the SFYs 2022-2023 biennium budget, allow families with children who are not enrolled in school districts to apply for and receive the Adequate Education Aid that would have been granted to the local school district if the student had attended school there. Money in EFAs may be used by parents for a wide variety of education-related expenses, including tuition and fees at a private school, internet services and computer hardware primarily used for education, non-public online learning programs, tutoring, textbooks, school uniforms, certain therapies, and other expenses approved by a State-recognized scholarship organization.

Under the separately-passed Senate Bill 295, EFAs were made universally available to all New Hampshire residents eligible to enroll in public K-12 schools. The new State Budget includes language that would remove the EFA enrollment cap, which would initially be set at 10,000 students, if the cap is not increased for two consecutive years. Students meeting “priority guidelines” will be eligible for an EFA even if the enrollment cap has been met. “Priority guideline” students are defined as students who:

- Currently receive an EFA

- Have a sibling receiving an EFA

- Experience a disability

- Are in a family with income less than or equal to 350 percent of the federal poverty guidelines

The Department of Education reported that $22.1 million was spent on EFAs in SFY 2024, while the cost was approximately $27.7 million in SFY 2025, totaling $49.8 million during the biennium.[xlii] The new State Budget appropriates $87.1 million in total for SFYs 2026 and 2027, or 119 percent more than the amount allocated in the past State Budget, and approximately 75 percent more than what was spent on EFAs during SFYs 2024 and 2025 combined. As with Adequate Education Aid, spending on EFAs matches the amount provided in law regardless of the number of students, and is not capped based on the amount of expenditures projected in the individual State Budget appropriation lines.

School districts no longer receive Adequate Education Aid associated with a student who leaves the district and enrolls in the EFA program; however, the State supplies two years of transitional funding after a student departs the district. Districts receive 50 percent of the original aid for a newly-disenrolled student in the year following a student’s departure, and 25 percent in the second year. The transition grants will not be provided to school districts for students who disenroll after July 1, 2026. The current budget includes $2.1 million to support these “phaseout grants” during SFYs 2026 and 2027.

A change in the new State Budget sends any unused budgeted EFA appropriations to the Education Trust Fund, rather than reinvesting them specifically in the EFA program.

School Building Aid

The new State Budget allocates approximately $14.8 million in SFY 2026 and $12.0 million in SFY 2027 toward school building aid, which would reduce this funding line by about $60 million (69 percent) from the SFYs 2024-2025 budget. The amounts appear to align with obligated payments to schools for SFYs 2026-2027 but would not allocate additional funding for new school building aid during the upcoming biennium.[xliii]

Cell Phone-Free Education

The new State Budget includes a requirement that school districts prohibit students from using cell phones and other personal electronic devices during the school day, from the beginning to the end of the day. The budget contains language that requires exceptions to the policy when cell phones are needed as part of students’ individualized education or 504 plans, or to support English language learning students.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiative Restrictions

The new State Budget includes language that creates a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) prohibition in public schools, including K-12, academic institutions, and institutions of higher education. The language defines DEI as “…characteristics identified under RSA 354-A:1…” Characteristics identified under RSA 354-A:1 include, “age, sex, gender identity, creed, color, marital status, familial status, physical or mental disability…national origin…[or] sexual orientation.” The Department of Education is directed to report to the Legislature about all existing DEI-related contracts in public schools, review all contracts, and report on the process for eliminating DEI-related provisions. Schools and institutions that do not comply with the prohibition may lose access to public funding until the violation is resolved.

Municipalities are also included in this provision. However, the new law does not indicate towns and cities would lose access to any funding if they do not comply with the DEI prohibition.

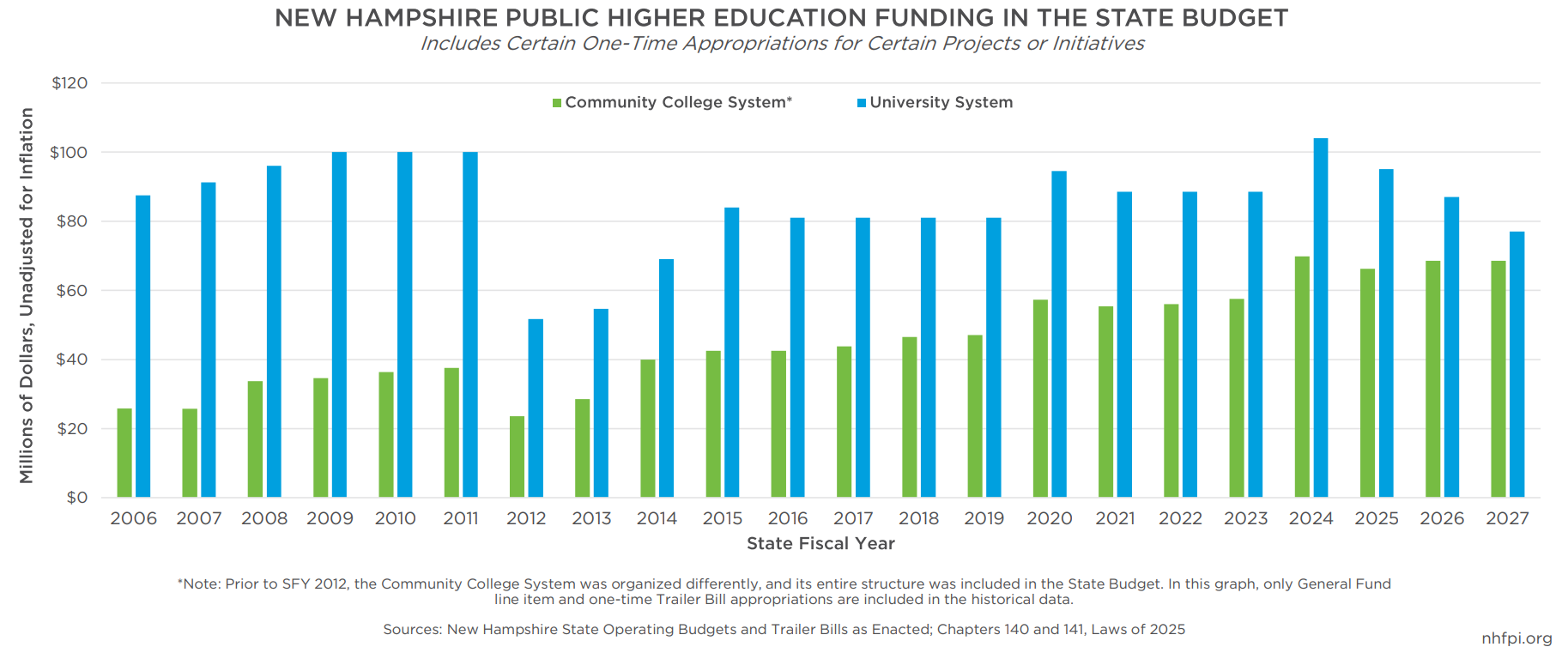

Higher Education

The new State Budget modestly increases funding for CCSNH by about 1 percent ($940,000) but decreases funding for USNH by 17.6 percent ($35.0 million) compared to the last biennium. The budget specifically allocates $3 million in CCSNH funding each fiscal year to dual and concurrent enrollment programs, which provide high school students in grades 10-12 with opportunities to take college courses. Additionally, $200,000 is allocated each year to math learning communities, allowing districts to offer certain CCSNH math courses at their schools. In SFY 2025, New Hampshire trailed all other states in public higher education funding when measured on a per capita basis as well as relative to the amount of personal income in the state.[xliv]

Housing

Despite appearing in multiple expenditure categories of the State Budget, funding dedicated to providing and expanding housing options makes up a relatively small portion of regular expenditures. State actions regarding zoning regulations, permitting changes, purchases of land, and other policy-related decisions can impact housing. However, there are only three areas where funding flows directly through the State Budget for initiatives that support resident access to housing or housing construction efforts each biennium in an ongoing fashion. They include:

- $5 million each State fiscal year in transfers from the Real Estate Transfer Tax to the Affordable Housing Fund, which provides grants and loans to developers looking to construct or rehab affordable housing for those with low and moderate incomes.

- Funding for the Judicial Branch’s Community Housing Program, which provides temporary housing to individuals involved with the criminal legal system who are also experiencing substance use disorders (SUD), including those participating in a drug court program or entering back into the community under parole or probation.

- Funding for the Bureau of Homeless Services, which provides support and resources for those experiencing homelessness or at risk of being unhoused, largely known as the Continuum of Care.

When combined, these three allocations total approximately $61.7 million across the $15.89 billion State Budget biennium for SFYs 2026 and 2027, or approximately 0.4 percent for all appropriations.

Included in the new State Budget is the maintenance of increased rates paid to shelters providing services; rates were first increased from $20 to $27 per day during the SFYs 2024-2025 biennium. According to the DHHS Division for Behavioral Health, $5 million will be allocated across the SFY 2026-2027 biennium for the preservation of these increased rates, which aligns with the DHHS’ agency budget request.

In addition to the $2.5 million each State fiscal year for increased rates paid to shelter programs, the new State Budget adds $10 million across the biennium from the State’s Opioid Abatement Trust Fund to expand services for people experiencing homelessness who are also experiencing opioid use disorder. All funding for homelessness services is located under the Bureau for Homeless Services’ budget lines, which will increase by $5.8 million (30.0 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026.

While new funding appropriated for the Housing Champions Program in the prior State Budget has not been repeated in the new biennium, the new State Budget extends funds appropriated during the SFYs 2024-2025 biennium that were set to lapse on June 30, 2025. In conversation with policymakers, Department of Business and Economic Affairs staff indicated that these remaining funds would be used up very quickly, although the extension may avoid any timing issues with contracts. The budget also establishes the Partners-in-Housing Program to promote the construction of affordable and workforce housing, although no funds were allocated for the program.

Housing Appeals Board Changes

The new State Budget reduces funding for the Housing Appeals Board, which was established in 2020 to serve as a parallel structure to the Superior Court System, focusing specifically on housing-related cases and disputes. Under the changes in the new State Budget, allocations for the Board would be reduced by $141,778 (24.3 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 ($584,410) and the budgeted amount for SFY 2026 ($442,632). Reductions in funding are primarily due to the elimination of a Board member, as the new Board will be reduced from three to two permanent members under the latest State Budget.

In addition to a reduction in funding, the budget also introduces administrative changes to the Housing Appeals Board, which will be housed under the Board of Tax and Land Appeals. Under the new structure, each Board will share decision-making processes, with members from opposite Boards able to make decisions and serve as tiebreakers if a consensus cannot be reached.

Expedited Permitting

The State Budget modifies the State’s permitting process for permits, approvals, or written authorizations related to shorelands, wetlands, water quality, and the construction of driveways off public roads, which may involve the development of new housing. Via policy language incorporated into the new State Budget, State departments reviewing environmental permit applications will be required to provide decisions within 60 days or less after receipt of a completed application. If a department is unable to provide a determination within 60 days, then the permit would be considered not an appreciable risk to a threatened or endangered species.

Applicants are able to provide written approval for extending the State timeline if they do not need a determination within the 60-day window. Any allotted time needed to collect additional information from applicants will not count against the State’s 60-day timeline.

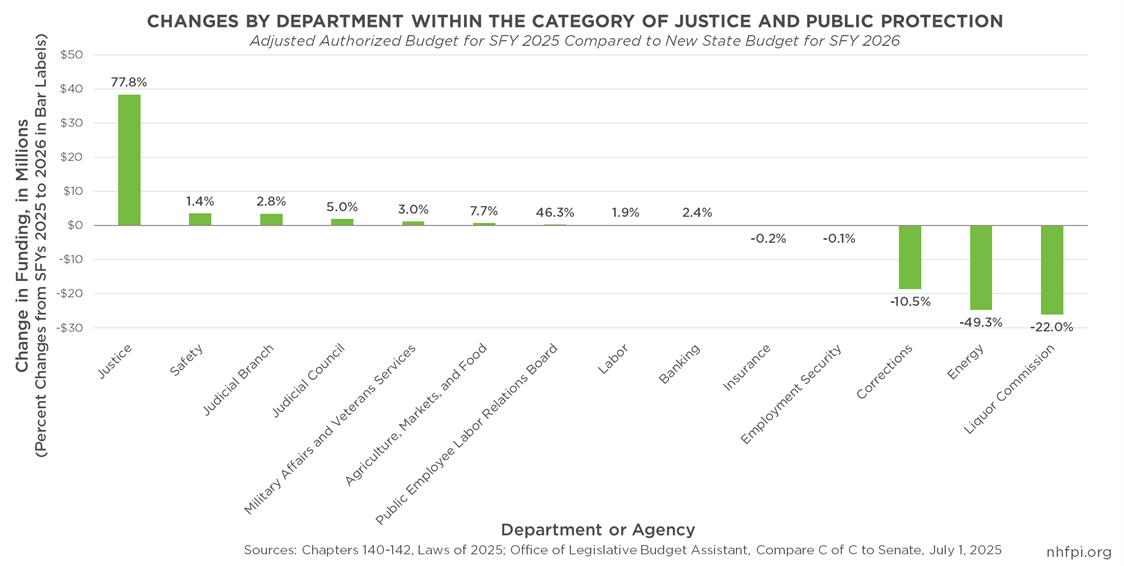

Justice and Public Protection

Key agencies within the Justice and Public Protection category of the State Budget include the judicial branch of State government, the Departments of Justice, Insurance, Safety, Banking, Military Affairs and Veterans Services, Energy, Labor, Corrections, Employment Security, and Agriculture, Markets, and Food. The Liquor Commission, Human Rights Commission, Judicial Council, and several other boards and offices are also within this category. Among the fourteen State departments and other agencies that are within the expenditure category of Justice and Public Protection, four have appropriation declines relative to the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized budgeted amounts in the new SFY 2026 budget. There are significant changes in appropriations in both directions.

The largest increase was in the Department of Justice, with a boost of $38.4 million (77.8 percent) between the two years. This increase was driven primarily by $30.0 million in appropriations related to the continued legal liability facing the State associated with the decades of alleged abuses of children in the State’s care at the former Youth Development Center and contracted agencies. The increase also includes $3.0 million designated for New Hampshire Child Advocacy Centers, $800,000 for the New Hampshire Internet Crimes Against Children Fund, and $3.5 million in federal funds from the Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Use Program during the biennium.[xlv]

The largest percentage increase in appropriations is at the Public Employee Labor Relations Board, a $261,331 (46.3 percent) increase from SFY 2025’s Adjusted Authorized appropriation to SFY 2026. A policy change attached to the State Budget increased the per diem payments to members of the Board from $50 to $250.

The Department of Safety was appropriated $600,000 specifically for the Northern Border Alliance to support law enforcement efforts near the Canadian border, and $75,000 in each year of the biennium to support training for Emergency Medical Services personnel to address rural maternal health concerns. The Department of Safety was also appropriated $3.5 million from the Opioid Abatement Trust Fund to support local law enforcement substance abuse enforcement program efforts in Carroll, Coos, Grafton, and Sullivan counties.

The largest decreases were at the Liquor Commission (-$26.1 million, -22.0 percent), the Department of Energy ($24.7 million, 49.3 percent), and the Department of Corrections (-$18.6 million, -10.5 percent). The changes at the Liquor Commission stem almost entirely from the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized budget showing funding transfers to other State agencies, including the DHHS to help fund the non-federal share of Medicaid expansion and to addiction recovery services, that the SFY 2026 budget did not include among appropriated transfers.

The Department of Energy’s funding reduction is the result of transferring or diverting a total of $24.0 million away from the Renewable Energy Fund during SFY 2026. The Department of Corrections budget has both a $10.0 million back-of-budget reduction and 54 positions eliminated during the biennium.

Department of Corrections Changes

The total of 54 jobs across the Department of Corrections are eliminated in the new State Budget includes a wide array of State positions. The largest number of positions eliminated within the Department are in mental health services (6 positions), dental services (5), human resources (5), and at the State prison for men (5). Positions were also eliminated at the pharmacy, residential treatment program, transitional work center, business information unit, maintenance, inventory, and at the district offices and the Northern New Hampshire Correctional Facility and the correctional facility for women.

The Department will also have to identify $10.0 million in savings to comply with a back-of-budget reduction. The new State Budget specifies the components of the Department’s budget within which $2.0 million of those $10.0 million in savings have to be identified, unlike the other back-of-budget reductions in the State Budget, which provide only a broad mandate for reductions without specificity.

Youth Development Center Settlement Funding and Policy

The new State Budget will appropriate $20.0 million to the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund. This Fund is designed to help address legal claims against the State by victims of alleged abuse over decades at the Youth Development Center. Based on current State law, the Fund may pay up to $75.0 million per year in settlements, so these appropriations will provide support for only a portion of that liability.[xlvi]

The new State Budget would also require the sale of the physical buildings and location currently named the Sununu Youth Services Center in Manchester, and direct the proceeds from that sale to the Fund. The amount expected from the sale was not specified in the State Budget, although some policymakers discussed a figure as high as $80.0 million during budget negotiations.

According to a July 24, 2025 report from the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund’s administrators, as of June 30, there were 1,530 claims against the State made through the program, and 386 claims had been settled with a total cost of $221.7 million to the State, including interest costs. The total pending claims requested by individuals seeking settlement with the State was about $1.84 billion.[xlvii]

Separately, the new State Budget appropriates $10.0 million to address a single case from a former Youth Detention Center resident who had sued the State in court, rather than using the Settlement Fund process.

The new State Budget also shifts the responsibility for the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund’s management and oversight from the Judicial Branch to the Executive Branch, putting it under the purview of the Governor.

Human Rights Commission

The Human Rights Commission is authorized by a statute passed in 1992. Per that statute, the Human Rights Commission exists “to eliminate and prevent discrimination in employment, in places of public accommodation and in housing accommodations because of age, sex, gender identity, race, creed, color, marital status, familial status, physical or mental disability or national origin…” This seven-member commission, administratively attached to the Department of Justice, receives complaints, holds hearings, conducts investigations, and issues publications related to the State’s laws against discrimination. In SFY 2023, the Commission reported receiving 767 inquiries and filing 243 charges.[xlviii]

The new State Budget includes a $521,000 back-of-budget reduction for the Human Rights Commission, which is the equivalent of 29.5 percent of its SFY 2026 approved budget of nearly $1.8 million. Because the back-of-budget reduction does not specify where savings must be found, agency personnel are required to decide which services and programs to cut.

The new State Budget also establishes a one-year advisory committee to be attached to the Human Rights Commission and study, monitor, and support the Commission in implementing corrective actions identified in a 2025 audit by legislative staff. Policy language also requires an annual report from the Human Rights Commission, requires that administrative rules for the Commission do not expire, adds oversight from the Department of Justice, and requires that the chair of the Commission be an attorney eligible to practice law in New Hampshire.

Renewable Energy Fund

The Department of Energy includes the Public Utilities Commission and its regulatory authority, and thus the Department falls into the Justice and Public Protection category of the State Budget.