New Hampshire’s State Budget, approved by the Legislature on June 22 and signed by the Governor on June 28, provides the basis through which most State activities are funded for the next two years. While the overall growth in this budget is slightly less than the growth of its predecessor, revenues projected to be available enabled the Governor and the Legislature to fund certain state-level priorities. This State Budget, both through appropriations and policy changes, emphasizes care for children and youths, including through child protection, mental health care, substance use disorder treatment, and juvenile justice changes, relative to certain other priorities. Funding for certain health and human services operations received significant increases, and two departments underwent major structural reorganizations. Substantial tax cuts for businesses were enacted, with the potential for future revenue declines that are not likely to be fully offset by increased revenue from the expansion of lottery sales through the internet, which is also permitted by the State Budget.

This Issue Brief compares the State Budget, as approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor, to its predecessor as passed during the 2015 Legislative Session. For more on the iterations of the State Budget during different phases of the 2017 Legislative Session, see the “NH State Budget” web page at nhfpi.org.[1]

The Topline Numbers

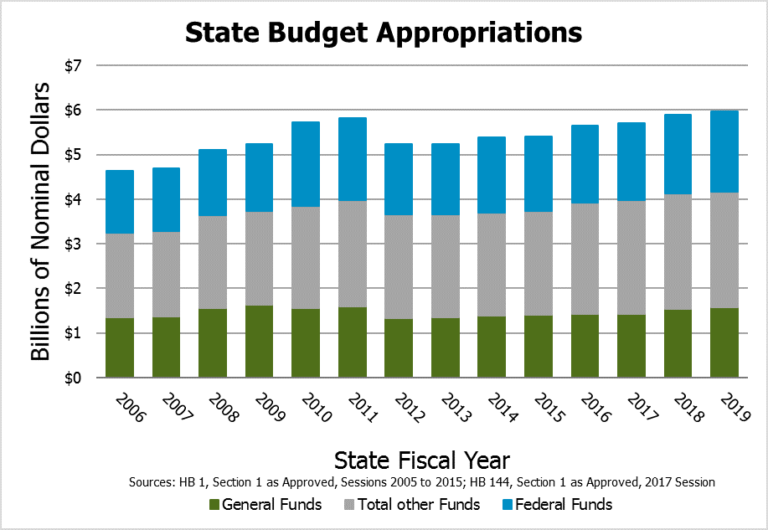

The State fiscal years (SFY) 2018-2019 State Budget appropriates $11.855 billion[2] for the biennium through Section 1 of House Bill 144, the primary budget bill, which authorizes the amount of money agencies may spend and source from certain funds. The $11.855 billion is split between $5.890 billion in SFY 2018 and $5.965 billion in SFY 2019, which continues a trend in incremental annual increases in appropriations through the State Budget since 2013, unadjusted for inflation. These two nominal dollar figures represent the first time the State Budget’s appropriations have surpassed the previous high of $5.815 billion (unadjusted for inflation) in SFY 2011, when the Great Recession[3] and the subsequent slow recovery had led to increased demand for anti-poverty and economic hardship programs and revenue increased through federal transfers from economic recovery programs.

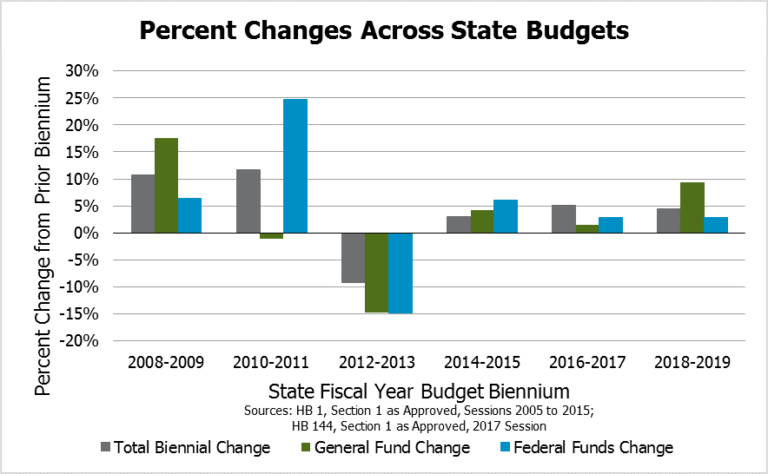

Relative to the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget as enacted in the 2015 Legislative Session, the SFYs 2018-2019 budget grows by 4.4 percent in overall appropriations. This percentage falls between the 5.1 percent growth of the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget relative to the SFYs 2014-2015 State Budget and that budget’s 3.0 percent growth relative to its post-Recession SFYs 2012-2013 predecessor. The General Fund, which makes up 26.2 percent of the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget and is the vessel holding unrestricted funds for legislators to appropriate, grew by 9.2 percent after two biennial budgets of slower growth relative to their predecessors (1.4 percent and 4.3 percent). The two budgets before those saw shrinking General Funds during and after the Great Recession (-14.8 percent and -1.1 percent). Federal funds, which provide revenue for 30.0 percent of the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget appropriations, grew roughly in line with the last biennial State Budget’s federal funds growth compared to its predecessor.

Other Appropriations

Certain appropriations were made as part of the budget process outside of Section 1 of the primary budget bill, House Bill 144. House Bill 517, the omnibus budget trailer bill which includes supporting language and other policy changes, appropriates an additional $700,000 in SFY 2018 and $250,000 in SFY 2019 for certain expenditures.[4] House Bill 517 also authorizes the transfer of undesignated surplus money from SFY 2017, which reduces appropriated expenditures in House Bill 144 by sourcing funds from outside those collected under the SFYs 2018-2019 budget timeframe. From the SFY 2017 surplus, House Bill 517 appropriates $5.0 million to the Governor’s Scholarship Program, which reduced the total budget appropriations relative to earlier discussed versions of the budget. Additionally, House Bill 517 appropriates $2.25 million of SFY 2017 surplus to school building aid projects, which did not add to the total budget. House Bill 517 also allocated $13.9 million in SFY 2017 surplus funds to the Highway Fund to pay for expenditures budgeted in SFYs 2018-2019; those appropriations were included in House Bill 144, Section 1, as appropriations sourced through the Highway Fund.[5] The graphics and other analyses in this Issue Brief reflect figures from House Bill 144, Section 1 unless otherwise indicated. The Legislature also assumes a lapse, or an amount of money agencies will not spend from their legally authorized budget appropriations; the Governor and the State agencies are supposed to work together to meet this lapse target, but are not directed by statute to do so. The assumed lapse is not included in the analyses in this Issue Brief, as the lapse is not in statute nor are expected lapse amounts distributed among State agencies by the Legislature.

Several other bills this session appropriated dollars outside of the State Budget, including surplus dollars for infrastructure spending and closing budget shortfalls associated with Medicaid payments, and boosts for full-day kindergarten adequate education grants during the upcoming biennium. These bills are not discussed in this Issue Brief.[6]

Agency Funding Changes

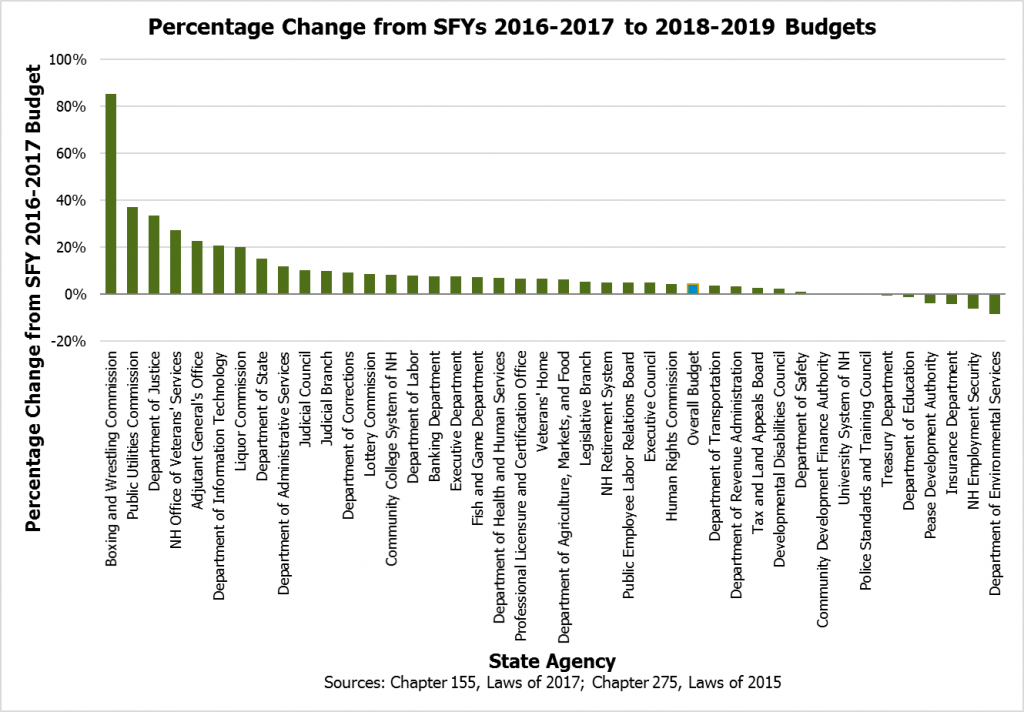

Although the overall State Budget grows by 4.4 percent relative to its predecessor, that growth is not evenly distributed throughout the State agencies. Some agencies are granted large percentage increases in their appropriations, while a handful face declines in budgeted appropriations. Changes in actual dollar appropriations reveal which agencies receive more of the new dollars appropriated, and convey a somewhat different story.

Percentage Changes in Agency Funding

Four agencies receive a more than 25 percent increase in funding relative to their SFYs 2016-2017 appropriations: the Boxing and Wrestling Commission (85.4 percent), the Public Utilities Commission (37.2 percent), the Department of Justice (33.7 percent), and the New Hampshire Office of Veterans’ Services (27.2 percent). The Boxing and Wrestling Commission is one of the smallest budget line items; the net increase for the biennium is $6,389, which translates into a large percentage increase relative to the SFYs 2016-2017 total appropriation of $7,477. The Public Utilities Commission’s funding boost of $15.9 million over the biennium stems primarily from increasing expenditure authority for the Energy Efficiency Fund ($6.5 million increase), which receives money through allowance sales through the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, and the Renewable Energy Fund ($7.0 million increase), which collects money from electricity providers that do not meet the State’s Electric Renewable Portfolio Standard. Neither of these appropriations are an increase in General Fund appropriations, but a change in expected agency income.[7] The Office of the Commissioner at the Public Utilities Commission received a

$1.6 million increase as well. The Department of Justice increase primarily stems from federal grants to aid crime victims. The New Hampshire Office of Veterans’ Services, financed by the General Fund, receives a $280,210 increase for the SFYs 2018-2019 biennium.

Other notable increases include a boost in funding for Corporate Administration and Securities Regulation at the Department of State, with decreased funding for the Elections Division. The Department of Administrative Services sees increased appropriations for State employee retiree health payments, including increased contributions from retirees themselves, and smaller declines in property and plant management and accounting services. The Administrative Services Commissioner’s office has increased appropriations partially due to the addition of the Office of the Child Advocate, a new entity that will exercise oversight of the Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) Division of Children, Youth, and Families. The Department of Corrections, which is mostly funded by General Funds, received a total increase of 9.4 percent; the Department is expected to open a new prison for women during this biennium. The Community College System of New Hampshire received an 8.4 percent boost in General Funds, while the University System was the only agency that was flat-funded from the previous budget. The DHHS, which is the largest State agency and accounts for 40.2 percent of spending in the SFYs 2018-2019 budget, sees its appropriations grow by 7.0 percent. The Executive Department grows in part due to the new Governor’s Scholarship Program adding $5.0 million for the biennium to the Office of Strategic Initiatives (formerly the Office of Energy and Planning and renamed by the State Budget) and a nearly $1.1 million increase to the Executive Office’s budget.

The decrease in appropriations at the Department of Environmental Services (DES) is primarily due to the removal of $80 million of federal grants and repayments from certain clean water and drinking water revolving loan funds, with the expectation that the funds will be authorized, accepted, and moved as needed by the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee during the biennium and therefore do not appear in the budget.[8] The DES Waste Management and Water Pollution Divisions receive substantial increases in funding. The net reduction in budgeted appropriations at the DES is $31.9 million relative to the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget.

Other significant percentage reductions include a 6.0 percent ($4.5 million) reduction at New Hampshire Employment Security, a 4.2 percent ($1.1 million) reduction at the Insurance Department, and a 3.9 percent ($52,242) reduction at the Pease Development Authority.

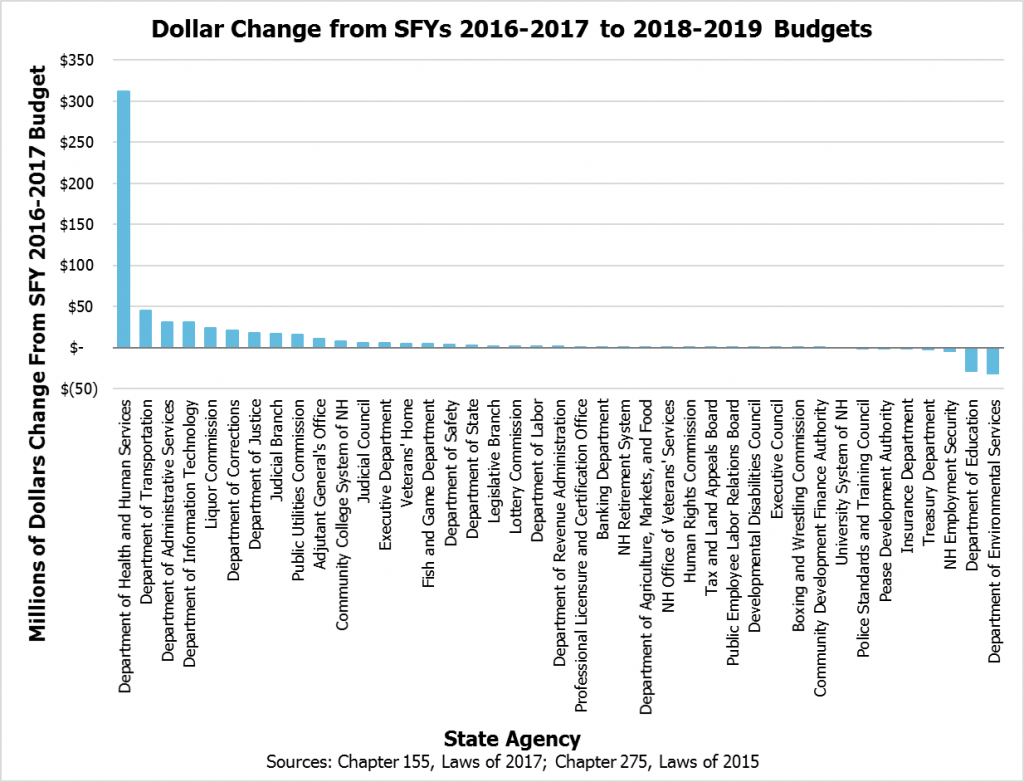

Dollar Amount Changes in Agency Funding

Examining changes in dollar amounts reveals the 7.0 percent increase in funding at the State’s largest agency dwarfs other changes. The DHHS sees an increase of $312.4 million to its budget to $4.762 billion for the biennium, which was less than the $4.897 billion the agency requested in its Efficiency Budget proposal but over $267.4 million more than the $45.0 million increase received by the next largest dollar increase at an agency, which was the Department of Transportation. (This Issue Brief explores more of the funding changes at the DHHS below.)

The largest dollar decreases are at the DES, due to the removal of federal revolving loan funds from the State Budget (as discussed above), and the Department of Education (DOE), which saw a 1.1 percent ($28.5 million) reduction. At the DOE, about $15.6 million in federal grants were in the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget for special education students in elementary and secondary education that are not present in the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget; in a similar move to the DES’s revolving loan funds, those dollars are expected to be authorized as necessary by the Fiscal Committee.[9] The DOE funding reductions are also due to revised expectations for adequate education grant payments resulting from declining student population and enrollment. Adequacy grants to non-charter public schools decline by $25.8 million in the SFYs 2018-2019 budget relative to the prior budget. Aggregate charter school payments are increased by $6.1 million over the biennium, but that increase also includes boosts in per-student tuition payments relative to SFY 2017 of $250 in SFY 2018 and $375 in SFY 2019, except for the Virtual Learning Academy Charter School.

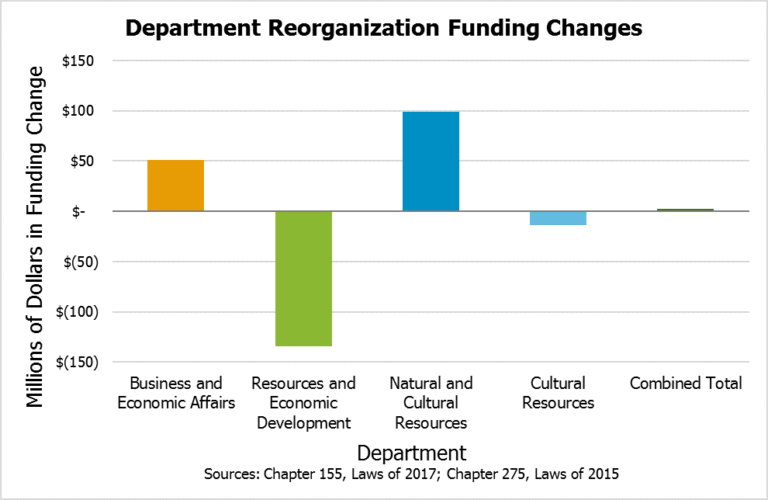

Department Reorganization

Two key departments are not included in the inter-budget funding graphical comparisons above due to a departmental reorganization required in the State Budget. The Departments of Resources and Economic Development (DRED) and Cultural Resources (DCR) are reorganized into the new Department of Business and Economic Affairs and the new Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. This change moves the Divisions of Libraries, Arts, Film and Digital Media, and Historical Resources from the former DCR to the new Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, where those divisions are joined by the Division of Forests and Lands and the Division of Parks and Recreation, both from DRED. The Department of Business and Economic Affairs gains the Division of Economic Development and the Division of Travel and Tourism, both formerly part of DRED.

Overall, this change results in reorganizing one $134.1 million per biennium department, DRED, and one $14.0 million per biennium department, DCR, into two departments closer to one another in size, the Department of Business and Economic Affairs ($51.3 million per biennium) and the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources ($99.3 million per biennium). The total increase in funding for the two new departments relative to the former departments in the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget is just under $2.5 million for the biennium, or 1.7 percent growth overall. The reorganization also includes a redistribution of the funds collected through the conservation plate program between the new departments, and the permitted uses for those funds expands.

DHHS Program Changes

Although changes in funding unit categorizations in the State Budget limit certain direct comparisons within the DHHS, certain activities receive significant increases in funding. The appropriation for payments to providers for those with developmental disabilities increases $53.9 million relative to the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget as passed, and the Office of Medicaid Business and Policy also receives a major funding boost associated with Medicaid payments and budget line reorganizations. The Bureau of Child Protection receives a $20.1 million funding boost between the two budgets (including a $1.0 million increase for domestic violence crisis centers), and the Child Development Bureau sees a funding increase of nearly $15.1 million. The DHHS Commissioner’s Office also receives a $19.6 million increase, $14.4 million of which is set aside specifically to increase compensation for individuals providing medical services paid through the DHHS. Other activity units receiving an increase of over $10 million over the prior biennium include the Bureau of Mental Health Services, the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services, the Bureau of Community Health Services, and the Division of Family Assistance. Declines in budgeted funds for the DHHS came through moving federal and other funds through different authorizing mechanisms outside of the State Budget, including $70.1 million for the Medicaid-to-Schools program and $32.0 million for the Bureau of Infectious Disease Control’s vaccine purchases.

Programmatically, these increases in funding are budgeted to provide certain expanded services. The DHHS is required to seek vendors to provide 20 transitional and community residential mental health beds in SFY 2018, and up to 40 beds in SFY 2019, with wrap-around support services for individuals. Up to 20 designated receiving facility mental health beds are also funded, as is one mobile crisis team and associated apartments for housing. The State Budget also funds a Medicaid home and community-based behavioral health services program for children with severe emotional disturbances whose needs cannot be met through traditional behavioral health services, which includes wrap-around care coordination and participation, in- and out-of-home respite care, and family and youth peer support. Additionally, the State Budget links the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families monthly cash benefit for families to a maximum of 60 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, with annual adjustments.

Excess capacity at the Sununu Youth Services Center will also be redeveloped to provide inpatient and outpatient drug treatment services for eligible individuals under age 18. Funding for the drug treatment facility at the Sununu Youth Services Center may be funded through the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund (AAPTF), and at the request of the Governor and with the approval of the Fiscal Committee, Center operations generally may be funded through the AAPTF. The percentage of Liquor Commission gross profits allocated to the AAPTF increases from 1.7 percent to 3.4 percent.

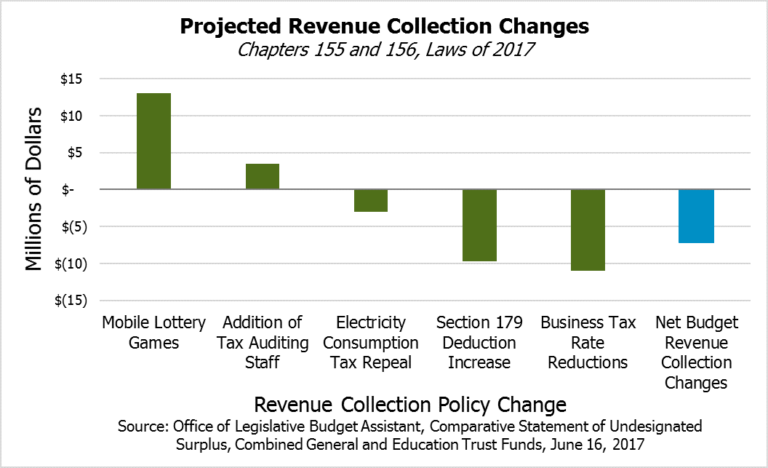

Revenue Policy Changes

The SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget makes some significant changes to revenue collection, the latest of which will not take effect until 2021. While certain other policy changes are projected to affect revenue collections, three major changes to taxation, the expansion of State-sanctioned gaming options, and changes to Department of Revenue Administration (DRA) staffing comprise the most notable changes. The net decline in revenue budgeted due to these changes during the SFYs 2018-2019 biennium is $7.2 million, although greater reductions in revenue are likely to result from these policy changes in future biennia.[10]

Gaming

The new policy projected to collect the largest amount of revenue is internet and mobile lottery ticket sales. The Lottery Commission is, under this State Budget, permitted to sell lottery tickets directly over the internet if players register for an account at a lottery retailer, which will include a verification of the player’s age as being at least 18 years. Transactions must be limited to purchases from within New Hampshire’s geographic boundaries, and there must be wager limits for daily, weekly, and monthly amounts for each player to address problem gambling. This revenue source is expected to bring in $13 million over the course of the biennium.

The legalization of Keno gaming, associated with the increase in the adequate education grants for municipalities with full-day kindergarten, is not included in the State Budget. Keno legalization was passed separately as Senate Bill 191.[11]

Department of Revenue Administration Auditors

The Legislature allocates more resources to the Department of Revenue Administration to establish three new positions that would focus on collecting taxes. Two audit positions, a field audit team leader and a multi-state auditor, will join a new compliance officer to collect an estimated additional $3.5 million during SFYs 2018-2019, which would provide substantial net revenue after the roughly $0.5 million required to pay for these positions.[12]

Tax Law Changes

Three tax law changes passed as a part of the State Budget affect revenue substantially during the biennium, and the impact of one set of changes grows in subsequent years.

First, the State Budget repeals the Electricity Consumption Tax. This tax of $0.00055 per kilowatt hour applied to all electricity users and produced approximately $6 million of revenue annually. The repeal takes effect January 1, 2019, which reduces State revenues by an estimated $3.0 million during the biennium.

Second, the State Budget expands a Business Profits Tax (BPT) deduction for businesses. The change permits expense deductions for certain allowable purchases of property, starting in 2018, to rise to $500,000. This follows an increase of this deduction from $25,000 to $100,000 for 2017, and is estimated to reduce revenues by $9.7 million during SFYs 2018-2019.

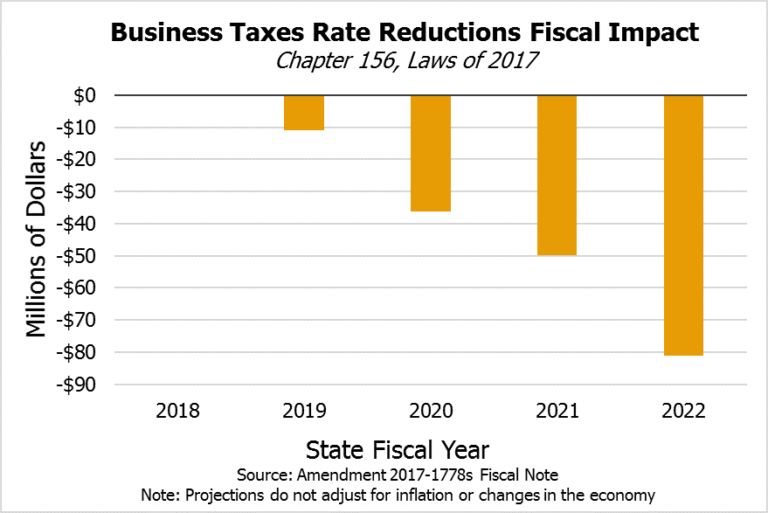

Third, phased reductions in two key business tax rates will likely produce the largest impact on future revenues of any of these changes. Approximately 90 percent of businesses use a calendar year as the tax year, so the revenue effects of tax law changes are often split across State fiscal years. The BPT, set at 8.2 percent for 2017, will be reduced to 7.7 percent in 2019, and 7.5 percent in 2021. The BPT is likely to be reduced from 8.2 percent to 7.9 percent for 2018, as a reduction in the rate would be triggered by a law passed in the 2015 Legislative Session and based on a revenue target for SFYs 2016-2017 that preliminary information suggests has been met.[13] The BPT was set to 8.5 percent in 2015, where it had been since 2001. BPT revenues are split between the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund, the latter of which receives revenues resulting from 1.5 percentage points of the BPT rate.

The Business Enterprise Tax (BET) rate also changes under the State Budget, dropping to 0.6 percent in 2019, and 0.5 percent in 2021, from the 2017 level of 0.72 percent. The revenue triggers discussed above will likely lead to a BET rate reduction for 2018 to 0.675 percent. The BET was set to 0.75 percent in 2015, where it also had been since 2001. The Education Trust Fund receives the first 0.5 percentage points of the BET rate, and the remainder goes to the General Fund for unrestricted use. Dropping the BET to 0.5 percent, 33 percent below where the rate was in 2015, will require all dollars collected by the BET to go to the Education Trust Fund, making this relatively stable and important revenue source for the General Fund disappear unless dollars are later transferred from the Education Trust Fund to the General Fund.[14]

The Department of Revenue Administration, using static revenue estimates (i.e., not accounting for inflation, changes in the economy, or other revenue volatility), estimated these business taxes rate reductions may reduce revenue by $11.0 million in SFY 2019, $85.9 million in the SFYs 2020-2021 budget biennium, and $81.1 million in SFY 2022 alone.[15] The dollar amounts foregone are likely to be larger due to inflation, and growth patterns in the economy are difficult to predict. Reducing tax rates substantially increases the risk that revenue sufficient to fund ongoing operating expenses will not be collected.

Other Policy Changes

The State Budget’s trailer bill, House Bill 517, also makes many policy changes that were not necessarily directly related to changes in appropriations for expenditures. However, certain changes alter funding streams for these appropriations.

New Hampshire Health Protection Program Work Requirements

Although the New Hampshire Health Protection Program (NHHPP), which is the State’s version of expanded Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, is not funded through the State Budget, House Bill 517 includes a requirement that the State apply to the federal government for a waiver to include work requirements for certain participants in the NHHPP. The State Budget language requires the DHHS to seek waivers to require newly eligible unemployed adults who do not meet certain conditions, including exemptions for certain situations related to illness and caring for children, to spend 20 hours per week employed, collecting work experience or on-the-job training, searching for jobs, or participating in certain education programs. The weekly hour requirement would increase to 25 hours after one year benefitting from the NHHPP and 30 hours after two years. Should the federal government not grant a waiver to permit New Hampshire to enact these work requirements by the end of April 2018, the NHHPP shall not be reauthorized and participants would be notified of the program’s end date, which is in December 2018.

Retired State Employee Health Premium Contributions

The State Budget requires that retired State employees contribute to their health insurance premiums, with an exemption for employees born in 1948 or earlier. Nonexempt retired employees eligible for Medicare Parts A or B due to age or disability would have to pay

10 percent of the total monthly premiums, with the Commissioner of Administrative Services having authority to increase the percentage with the approval of the Fiscal Committee. Those not eligible for Medicare would pay 20 percent of the health insurance premium cost, which is an increase from 12.5 percent set in statute prior to the passage of the budget.

Education

The trailer bill includes many other education-related provisions, including:

- The Governor’s Scholarship Program is established under the Office of Strategic Initiatives to provide funds to support certain eligible students who receive scholarships from in-state post-secondary institutions, which then apply for funds from the Program.

- The Community College System, the Department of Education, and school boards in each school district are required to create and facilitate a dual and concurrent enrollment program to permit qualified students in grades 11 and 12 to enroll in Community College System-designated science, technology, engineering, math, and related courses for high school and college or university credit while still attending high school or a career technical education center. Tuition costs for Community College System enrollment are paid through the Governor’s Scholarship Program.

- The State Budget establishes and financially supports a Robotics Education Fund, which is expected to receive donations for encouraging education in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Child Protection and Justice

The trailer bill also includes several non-appropriations provisions related to the care and management of young people in various situations. A few of these include:

- A joint legislative committee is established, with three members of the House and three members of the Senate, to examine the independent review of the Division of Children, Youth, and Families, and propose any recommended legislation.

- Certain definitions within the Child Protection Act are clarified, including the definition of an “unfounded report.” The State Budget modifies statute to permit those unfounded reports to be admissible in proceedings to establish a pattern of conduct.

- The extent to which minors may be committed to facilities for drug possession violations is limited, and minors may be retained for only 21 days or less while awaiting placement or hearing except in certain, court-approved circumstances. Other than cases involving serious violent offenses and where the minor consents to continued jurisdiction, all cases shall be closed within two years. Certain commitments of children for offenses which would be misdemeanors if committed by an adult also have additional limits posed on their durations.

- The DHHS must, by September 2017, develop a plan to move at least 35 minors who are not serious violent offenders from the Sununu Youth Services Center to Medicaid-eligible settings; the new settings must be available by January 2018. An advisory group to assist with juvenile justice reforms in the State Budget must also be formed and meet monthly.

Other Provisions

The trailer bill includes a multitude of other provisions, such as changes to the management of a wide variety of State government operations, clarifications in definitions, the establishment of small funds, and other directives. These wide-ranging and numerous provisions include:

- Revenue sharing with cities and towns continues to be suspended through the biennium. Meals and Rentals Tax revenue distributions to municipalities are held at SFY 2017 levels.

- Caps on county payments to the State for long-term care services are raised.

- For agencies receiving federal funds outside of the State Budget appropriations for conducting law enforcement activities that may result in increased court-determined indigent defense costs, five percent of such funds must be transferred to the Judicial Council to pay for resulting increased indigent defense costs.

- The Office of Strategic Initiatives is required to study biomass electricity generation in New Hampshire as it relates to the Electric Renewable Portfolio Standard and economic activity in the state.

- The Department of Transportation is authorized to study, in conjunction with the Liquor Commission, and acquire land for placing a service plaza at the location of the existing State liquor stores on Interstate 95 in Hampton. The language in the State Budget is modeled after the study of the Hooksett service plaza on Interstate 93.

- Provisions of law permitting the DHHS to pay for funeral expenses for certain eligible public assistance recipients are repealed.

- The number of judges serving on the Superior Court is capped at 21 and the number of full-time Circuit Court judges is capped at 33.

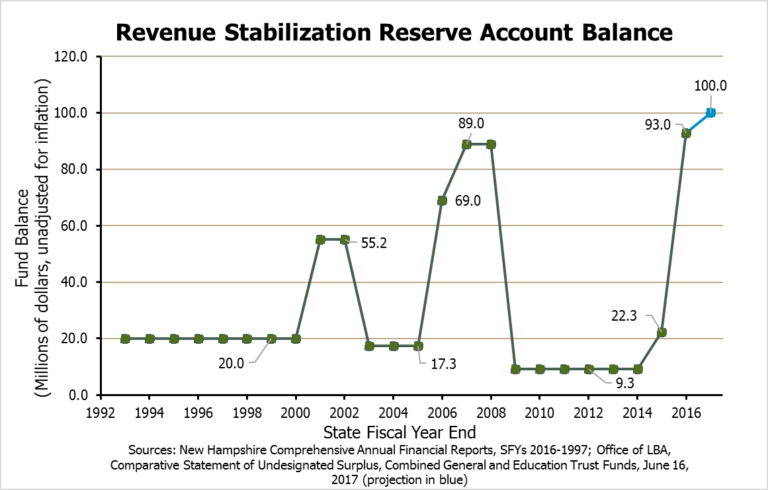

The Rainy Day Fund and Surplus Spending

The State Budget permits the Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account, also known as the “Rainy Day Fund,” to rise to a $100 million value with surplus dollars available from the SFYs 2016-2017 State Budget. The State Budget also modifies the Rainy Day Fund to permit transfers from legal settlements deposited in the Fund to exceed the current statutory cap, which is 10 percent of unrestricted General Fund revenues from the prior fiscal year.[16]

The remainder of the surplus available after other appropriations have been made are allocated to the newly-created Public School Infrastructure Fund. This Fund will be used by the Governor, in consultation with the Public School Infrastructure Commission and with the approval of the Fiscal Committee and the Executive Council, to provide school building aid to: 1) improve structures which are a clear and imminent danger or substantial risk to occupants, 2) support fiber optic connections to schools if matching funds are available, 3) provide funding for emergency readiness in schools, and 4) fund other school building or infrastructure needs not otherwise prohibited by law. The amount estimated to be included in the Public School Infrastructure Fund after the appropriations of surplus money from SFY 2017 for other purposes are completed is approximately $8.6 million.[17]

Looking Ahead to the Next Budget Cycle

With the State Budget enacted for SFYs 2018-2019, most State agencies will begin working on their SFYs 2020-2021 budget requests by the summer of 2018, with an October 1 deadline for agencies to submit their expenditure requests.[18] The Governor elected or re-elected in the 2018 elections will then submit a proposed budget to the new Legislature by February 15, 2019. In the interim, the Fiscal Committee will meet to manage the budget as necessary, and the Legislature may pass additional bills altering appropriations. All of these actions will inform the development of the next State Budget.

The State Budget represents New Hampshire’s priorities; the decisions and investments the Governor and Legislature make with public resources should reflect the values and desires of the people represented by these elected officials. While the two-year cycles of the budget process hamper certain efforts at long-term planning, key investments and policy decisions should be made as part of the biennial budget process. As planning begins for the next budget, policymakers should research, understand, and determine the best ways to lay the groundwork for a healthy and prosperous future for all New Hampshire residents, and incorporate those priorities into their decisions while building the next budget.

Endnotes

[1] See the NH State Budget web page.

[2] The $11.855 billion total does not reflect changes in House Bill 517, the trailer bill, and does not reflect the lapse amounts. The lapse is an assumption and is not in statute as a limitation on State agency spending. Including the estimated lapse and the House Bill 517 changes, the total size of the State Budget is $11.727 billion. For a breakdown of these topline numbers, see the HB 144 and HB 517 Committee of Conference Budget Briefing, June 20, 2017.

[3] Referencing the December 2007 to June 2009 recession, see the National Bureau of Economic Research, Business Cycle Dating Committee, September 20, 2010.

[4] House Bill 144, as approved by both the House and the Senate, became Chapter Law 155, Laws of 2017. House Bill 517, as approved by both bodies, became Chapter Law 156, Laws of 2017.

[5] See the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus, Combined General and Education Trust Fund, June 16, 2016 and Surplus Snapshot, Combined General and Education Trust Fund Surplus Statement Summary, June 14, 2017.

[6] For more on these bills and earlier iterations of the SFY 2018-2019 budget, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief on The State Senate’s Proposed Budget and NHFPI’s Common Cents blog posts on the Senate passage of its State Budget and the changes from the Committee of Conference.

[7] See RSAs 125-O:23 and 362-F:10, as well as Chapter 155, Laws of 2017, pages 222 and 223.

[8] See the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s HB 1, Section 1 Amendment, Appropriations Reductions, March 27, 2017, and Detail Change, Senate Passed (HB 144) vs. Governor Recommended (HB 1), All Categories, June 1, 2017.

[9] See Endnote #8 above, Chapter 155, Laws of 2017, page 778, and Chapter 275, Laws of 2015, page 782.

[10] For a list of changes in revenue sources for the General and Education Trust Funds, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Surplus Snapshot, Combined General and Education Trust Fund Surplus Statement Summary, June 14, 2017. For more on New Hampshire’s mechanisms for collecting revenue, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[11] See Senate Bill 191, 2017 Session.

[12] For more information on this change, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Senate Finance Committee Budget Recap Sheets and Amendments, May 15, 2017, page 36, and the Surplus Snapshot, Combined General and Education Trust Fund Surplus Statement Summary, June 14, 2017.

[13] For the triggered tax changes to the BPT and the BET, see RSAs 77-A and 77-E. The trigger amount for reducing the BPT and BET rates was set at $4.64 billion in General and Education Trust Fund unrestricted revenue for the SFYs 2016-2017 biennium. The June 2017 Monthly Revenue Focus suggests the State collected more than $4.8 billion in these two funds for this period. Per statute, the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, due to be finished by the end of December 2017, will provide the information necessary to make the final decision regarding tax rate changes for both the BPT and the BET.

[14] To learn more about these changes in business tax rates, see NHFPI’s Common Cents blog posts on proposed Business Enterprise Tax changes and the General Fund and the potential for business tax changes to increase certain revenue volatility. To see that the Education Trust Fund has only transferred money to the General Fund in two of the last ten years, see the State’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2016, page 136.

[15] See the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Business Tax Rate Reductions (HB 517), June 20, 2017.

[16] For more on the Rainy Day Fund, see NHFPI’s Common Cents blog post about the Rainy Day Fund.

[17] See the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus, Combined General and Education Trust Fund, June 16, 2016 and Surplus Snapshot, Combined General and Education Trust Fund Surplus Statement Summary, June 14, 2017.

[18] See RSA 9:4 and NHFPI’s Common Cents blog post on the efficiency budget process.