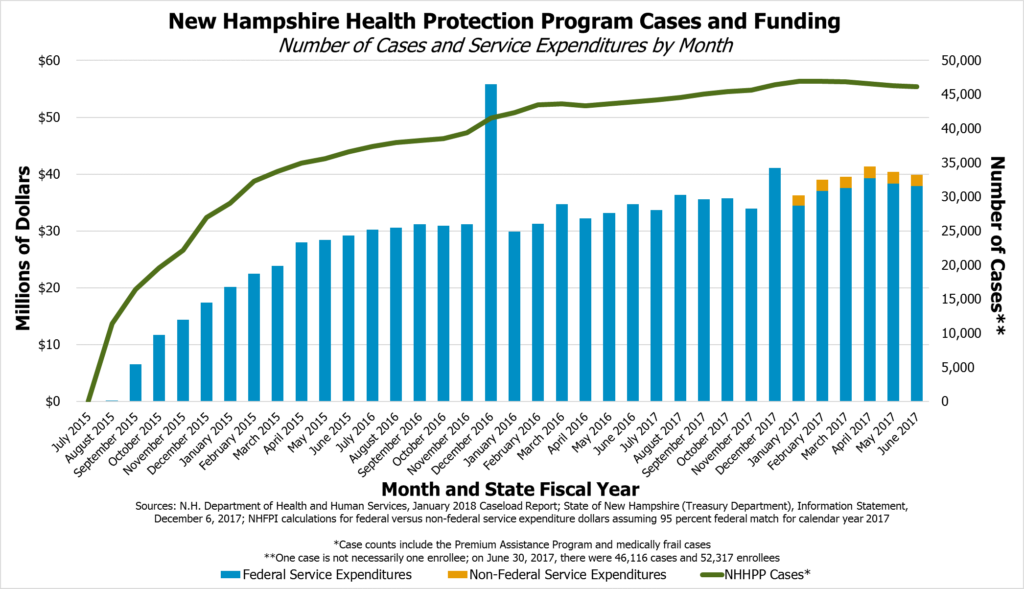

New Hampshire’s Medicaid expansion is an important program with impacts on the state’s public health and economy. Medicaid expansion provides health coverage to approximately 52,000 low-income people in New Hampshire, and more than 90 percent of program expenses have been funded by the federal government since the program began in 2014. Since that time, hundreds of millions of federal dollars have helped provide medical care for Granite Staters and contributed to the state economy, both through payments to medical providers and helping ensure a healthy, productive workforce, and assisting the state’s efforts to combat the ongoing opioid crisis. Federal dollars coming to New Hampshire through expanded Medicaid included $608.7 million for enrollee coverage in the first two State fiscal years of program operation.[i] Going forward under current federal law, for every one dollar New Hampshire pays for expanded Medicaid coverage, the federal government will contribute at least nine dollars. Without legislative action, the current program will expire at the end of December 2018.

This Issue Brief explains the framework of the existing Medicaid expansion program, considerations surrounding the program, and the State Senate’s proposed changes.

An Overview of Medicaid

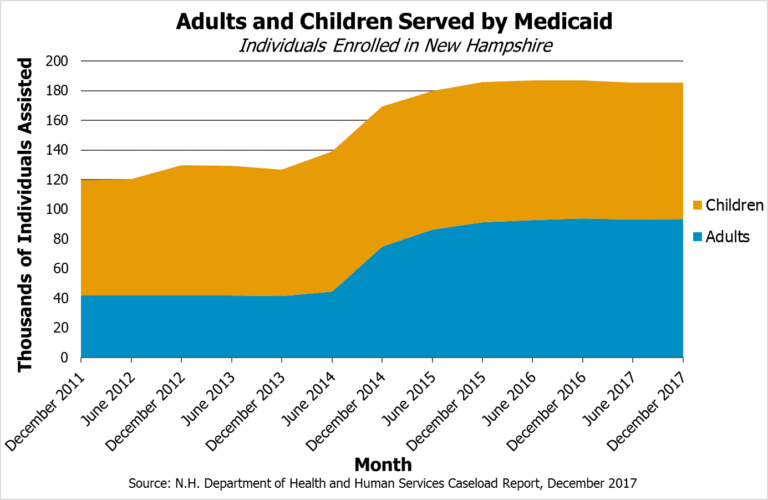

The Medicaid program is a partnership between the federal and state governments to eliminate or defray the costs of health coverage for specific populations with incomes below certain levels. Medicaid covers children, parents, pregnant women, people with disabilities, seniors and nursing home residents, and other individuals with low incomes. Certain portions of the Medicaid population are eligible for services through waivers granted to New Hampshire by the federal government, including services for those with developmental disabilities and certain seniors. Medicaid in New Hampshire serves over 180,000 people overall, about half of whom are children.[ii]

Medicaid is a major program in every state, with the federal government providing at least 50 percent of the funding for health coverage. Certain states and specific components of Medicaid have more favorable funding match rates for the non-federal share of costs, meaning the state has to contribute a smaller fraction of each dollar used to pay for health coverage costs through Medicaid.[iii]

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which became federal law in March 2010, the Medicaid program was expanded to cover adults who were not otherwise eligible for Medicaid and had incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline. Although originally required under federal law for a state to participate in the Medicaid program as a whole, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled participation in Medicaid expansion must be optional for states and must not be tied to participation in the remainder of the Medicaid program.[iv]

Expanded Medicaid in New Hampshire

In March 2014, the New Hampshire State Legislature passed and the Governor signed into law a bill establishing the New Hampshire Health Protection Program (NHHPP), which is New Hampshire’s version of expanded Medicaid. Initially, the program enrolled the newly-eligible population, which included previously-ineligible parents and childless adults under 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline, through the Medicaid managed care organizations (MCO), private firms that contract with the state to provide Medicaid health coverage management services. Most states that have expanded Medicaid enroll the newly eligible populations under a MCO model. However, New Hampshire sought a waiver from the federal government to permit these newly-eligible adults to use Medicaid funding to pay for premiums on the individual health insurance marketplace. The federal government granted this waiver in March 2015.[v]

The NHHPP was initially designed to require reauthorization to continue beyond December 31, 2016, with the authorizing statutes to be repealed if the Legislature did not intervene. The initial program services were funded entirely by the federal government, although certain administrative costs were paid in part by the state. When the program was modified and extended by the Legislature and Governor in April 2016, a funding mechanism was added to address the reduction in the federal share of service costs, and the program was extended through December 31, 2018. New Hampshire’s Medicaid expansion program requires reauthorization by the Legislature if it is to continue beyond this date.[vi]

The Medicaid program helps people access health care in the state, with 184,551 enrolled in the Medicaid program overall at the end of February 2018. That constitutes slightly under 14 percent of the New Hampshire’s entire population. Of those, the NHHPP specifically supported health coverage for at least 52,642 Granite State adults at the end of February 2018.[vii] As of November 28, 2017, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) reported that 130,900 individuals had been enrolled at some point since the start of the program.[viii] Qualifying enrollees must not otherwise be covered by a mandatory non-expansion Medicaid eligibility category, must not be enrolled in Medicare or be entitled to do so, and cannot be pregnant at the time of eligibility determination. Enrollees are aged 19 to 64 with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline, which was the equivalent of $16,643 for an individual, $22,411 for a household of two, and $28,180 for a household of three for 2017.[ix]

New Hampshire Medicaid Expansion’s Current Structure

NHHPP assistance is divided into three program areas based on enrollee eligibility.

The Premium Assistance Program (PAP) uses federal Medicaid reimbursement funds to pay for private sector health care premiums for low-income adults buying health insurance on the individual marketplace. PAP is the formal name for the portion of the program that required a waiver from the federal government to move the majority of NHHPP participants out of the MCOs. Certain benefits, such as non-emergency medical transportation, are provided directly through fee-for-service Medicaid in cases where they are not provided by private health insurance. The DHHS reported that, as of February 28, 2018, the NHHPP had 45,325 PAP enrollees, constituting most of the people served through New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid framework.[x]

NHHPP enrollees who are medically frail, such as those with physical, mental, or emotional conditions that limit their ability to perform daily activities or those who live in a long-term care facility, are covered through MCOs and not through the PAP on the individual marketplace. According to the DHHS, as of February 28, 2018, the medically frail portion of the NHHPP served 7,320 individuals, and enrollment in this category has trended upward over the existence of the NHHPP.[xi]

The Health Insurance Premium Payment Program assists eligible individuals and families in paying for employer-provided insurance by providing reimbursements for certain premium, co-payment, and deductible costs. This program was established as part of the original expanded Medicaid program’s structure in New Hampshire and retained a small number of enrollees. The DHHS reported that on August 1, 2017, this program included 81 enrollees.[xii]

Characteristics of Population Served

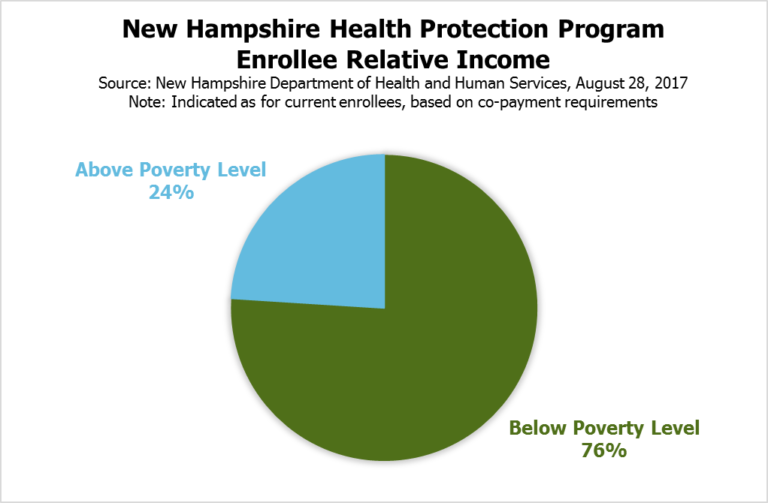

DHHS data, as presented on August 28, 2017, show that approximately 76 percent of NHHPP enrollees had incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty guideline. Enrollees with incomes greater than 100 percent of the federal poverty guideline are required to pay certain copayments for medical services. NHHPP enrollment is disproportionately young and includes a significant amount of turnover among participants. As of March 1, 2018, DHHS data indicate about 48 percent of current NHHPP enrollees are between 19 and 34 years old.[xiii]

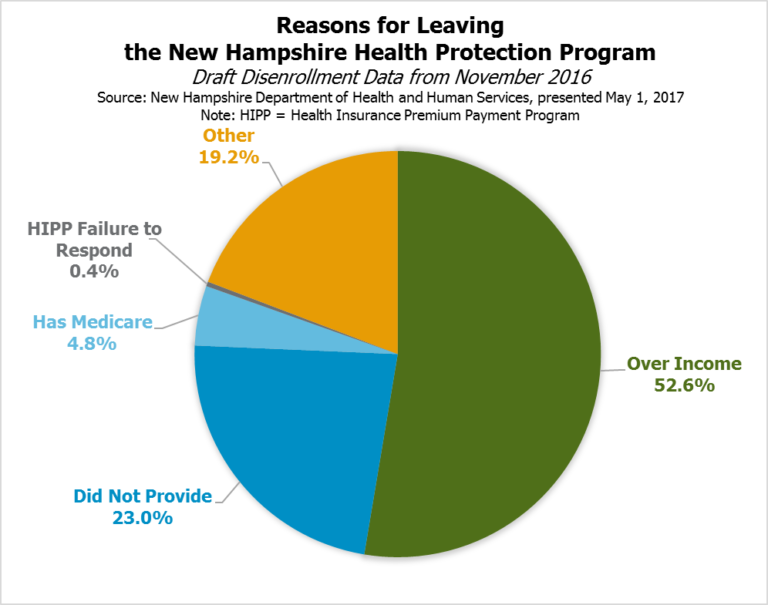

DHHS analysis of a two-year window, from April 1, 2015 to April 1, 2017, found 70.7 percent of recipients were not continuously enrolled throughout the time period. DHHS data from November 2016 indicate recipients tend to disenroll due to their incomes rising beyond the qualifying threshold; 52.6 percent reported disenrolling because of income, and the next largest group (23.0 percent) did not provide a reason for leaving the program. Historical data analysis from the Congressional Budget Office also suggests relatively high turnover and discontinuous enrollment rates among expanded Medicaid enrollees nationally. These fluctuations include people who are on the program for a period of time and never return as well as those who leave the program and return at a later date.[xiv]

Participation as a percentage of the population tends to increase with distance from southeastern New Hampshire, with a low of 2.72 percent of Rockingham County residents enrolled in NHHPP as of August 18, 2017, and a high of 6.17 percent of Coos County residents on the same date. Enrollment by municipality also shows similar geographic trends, with the highest number of enrollees as a percentage of the population in cities and towns from the Lakes Region north and the lowest percentages in the western Merrimack River valley, southeastern and Seacoast communities, and in certain places near Lake Sunapee, Lebanon, and Hanover. Considering New Hampshire’s three largest cities, Manchester had 7,717 enrollees on August 1, 2017, while Nashua had 3,951 and Concord had 2,253.[xv]

To learn more about the distribution of NHHPP enrollees and expenditures by municipality, see the Appendix in the PDF version of this Issue Brief.

Provided Services

In September 2017, the DHHS reported about 25,800 unique NHHPP enrollees completed preventative well care visits, 10,500 were screened for cervical cancer, 6,600 for breast cancer, and 4,700 for colorectal cancer since the program began. The DHHS also reported that approximately:

- 41,600 people received mental health services

- 23,400 received cardiovascular treatment services

- 16,000 received services for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- 11,000 received substance use disorder services

- 6,100 received treatment for diabetes

- 1,300 received cancer treatment services[xvi]

The New Hampshire Hospital Association reported, based on a survey of its membership, that while patient utilization of inpatient admissions, emergency visits, and outpatient hospital services increased between the periods of October 2013 to September 2014 and March 2016 to March 2017, use by uninsured patients dropped by over 40 percent in all three categories.[xvii]

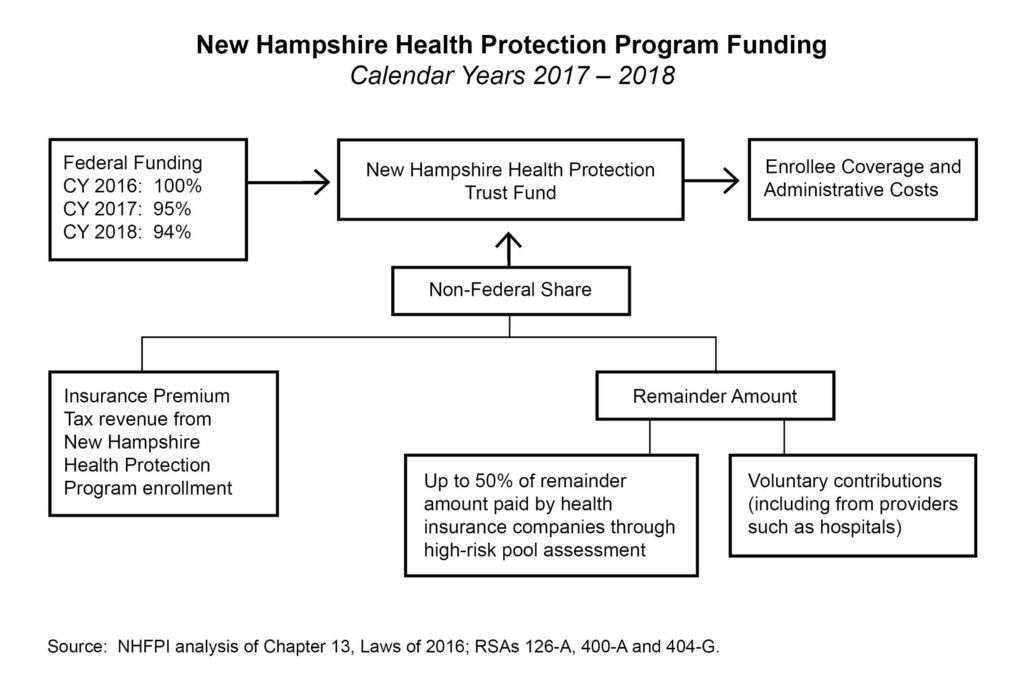

Funding the Non-Federal Share

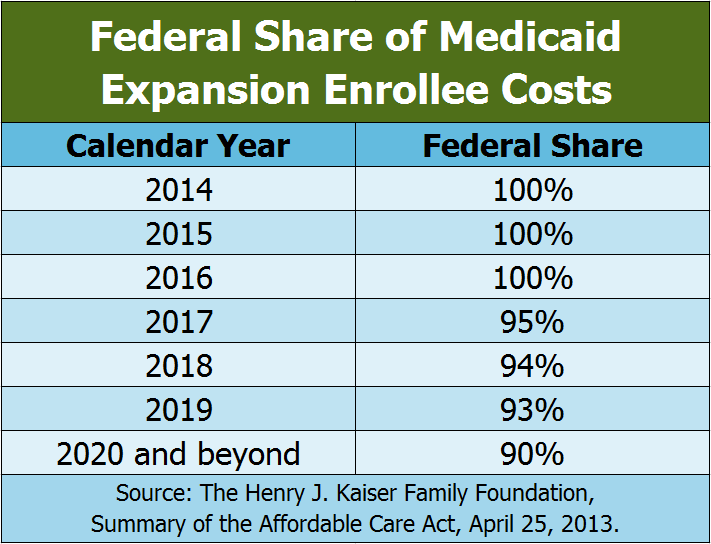

During calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016, the federal government paid for 100 percent of the NHHPP’s service expenditures. Starting in calendar year 2017, or halfway through the State fiscal year (SFY) 2017, which began July 1, 2016, the federal government paid for 95 percent of service expenditures, and the state was responsible for the remaining 5 percent. The percentage paid by the federal government is set to decline to 94 percent in calendar year 2018, 93 percent in 2019, and 90 percent for 2020 and all subsequent years; it does not drop below a 90 percent match under current law.[xviii]

To pay for the non-federal share as required in calendar years 2017 and 2018, the NHHPP draws on the New Hampshire Health Protection Trust Fund (NHHPTF). The Fund holds the federal revenue transferred to New Hampshire to pay for the NHHPP as well as the revenue to support the non-federal share. The non-federal share comes from a combination of the Insurance Premium Tax revenues attributable to the NHHPP population, an assessment paid by health insurance companies based on the number of individuals covered set at a fixed amount each year previously associated with a high-risk pool, and voluntary contributions to the NHHPTF. The last two sources are the “remainder” amount, which is essentially the non-federal share without the Insurance Premium Tax revenue. The assessment revenue is required to cover not more than 50 percent of the remainder amount. The voluntary contributions primarily come from hospitals and are delivered directly to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and not through the Department of Revenue Administration. Revenues deposited into the General Fund are not permitted to support the NHHPTF. If revenues are not sufficient, state law requires the DHHS to end the program.[xix]

In July 2017, the federal government identified concerns with the NHHPP reliance on donations from providers to fund the non-federal share and indicated New Hampshire may be out of compliance. The federal government indicated an expectation that the Legislature will make changes to the funding model, to be effective in SFY 2019, that will bring the state into compliance, and noted the state may face financial consequences if compliance is not achieved.[xx]

Program Expiration

Without action by the Legislature, the NHHPP will be repealed and cease to operate on December 31, 2018. To renew the program without increasing the risk of considerable disruption in the health insurance marketplace, and to permit time for any federal waivers required by State law to be reviewed and in place before January 2019, the Legislature is taking actions during the 2018 Legislative Session. Statute set forth in the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget requires a waiver from the federal government permitting certain work requirements to be in place by April 30, 2018. If the work requirements are not permitted by the federal government by April 30, the DHHS is required to “immediately, no later than April 30, 2018, notify all [NHHPP] participants that the [NHHPP] has not been reauthorized beyond December 31, 2018.”[xxi]

Premium Assistance Program Commission

The first reauthorization of the NHHPP, which became law in April 2016, established the Commission to Evaluate the Effectiveness and Future of the Premium Assistance Program (PAP Commission), which was required to evaluate the PAP’s financial metrics, program offerings, and impact on insurance premiums for individuals and small businesses. The PAP Commission was also required to make recommendations for future program modifications, including relative to the cost-effectiveness of the PAP model versus private market managed care, and evaluate longer-term non-General Fund options for supporting the NHHPP.[xxii]

The PAP Commission recommended reauthorizing the NHHPP to continue the expanded Medicaid program in New Hampshire. The PAP Commission also made six recommendations for changes and related additional data collection, summarized below:[xxiii]

- PAP participants should receive care through MCOs to reduce premium instability in the individual health insurance market and provide more opportunities to reduce premiums in 2019, remove the impact of those who are potentially medically frail on the individual market and better serve those who are medically frail, provide consistent benefits for all Medicaid recipients, and create a larger pool of participants in Medicaid to increase competition among MCOs.

- Reimbursement rates for medical service providers providing behavioral health services, including mental health services and substance use disorder services, should be higher than the existing Medicaid reimbursement rates, and higher rates in other service areas should also be considered.

- A transition period should be established to efficiently shift PAP participants into MCO care without any enrollees losing coverage due to this transition.

- MCOs should provide effective case management to ease transitions to health care exchanges when enrollee incomes rise beyond Medicaid expansion eligibility and continue to provide care and avoid member coverage lapses during these transitions.

- The DHHS, the New Hampshire Insurance Department, the Department of Revenue Administration, and the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant should work with PAP Commission members to provide information on possible changes in the levels of uncompensated care, Insurance Premium Tax revenue, and Medicaid Enhancement Tax revenue should all PAP enrollees be shifted to MCOs.

- New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program should be reauthorized for five years to be consistent with the timespan of federal waivers.

The PAP Commission did not explicitly or comprehensively compare or contrast differing funding options or make recommendations regarding funding options.

To reach these recommendations, the PAP Commission discussed a variety of topics.[xxiv] Policy options for screening for the medically frail categorization, rather than using the current policy of self-attestation, were considered to avoid having individuals who may have higher needs on the individual marketplace. The potential effects on premiums of different policy options for those who are not enrolled in the PAP or subsidized by the federal government were also considered in PAP Commission discussions. PAP enrollees accounted for approximately 44 percent of the individual marketplace in August 2017.[xxv] Strategies to alleviate some of the transition impacts of many individuals entering and exiting the program, particularly if moving from the PAP to an MCO model, and to reduce emergency room use relative to other venues to reduce expenses were also discussed.[xxvi]

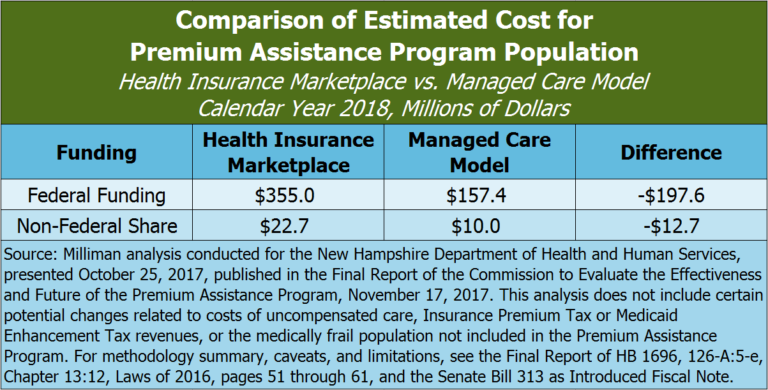

Cost-effectiveness was a key consideration for the PAP Commission. A DHHS-contracted actuary produced a cost analysis that modeled, for calendar year 2018, the estimated per member per month cost of having Medicaid expansion participants in the purview of the MCOs rather than on the individual health insurance marketplace under the PAP would be approximately 56 percent lower. This lower cost would be primarily due to the lower reimbursement rates for services that would be offered to medical service providers under a more traditional Medicaid arrangement through the MCOs than would be offered under the PAP, according to the analysis. The analysis projected, with certain caveats and limitations, that the non-federal share for the PAP population would be $10.0 million in the MCO model, rather than $22.7 million in the PAP model, for calendar year 2018. This analysis also showed a corresponding decline of $197.6 million in projected federal revenue flowing to New Hampshire from the change. The analysis did not include potential impacts to uncompensated care costs and disproportionate share payments to hospitals, the medically frail population currently served by the MCOs, Insurance Premium Tax revenue, or Medicaid Enhancement Tax revenue.[xxvii]

The State Senate’s Proposal

On March 8, 2018, the State Senate passed a revised version of Medicaid expansion called the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program (NHGAHCP). This program would replace the NHHPP, be authorized for five years, eliminate the current PAP and move current enrollees under the management of the MCOs, require the MCOs to take certain steps to provide incentives and continuity of care to program enrollees, implement work requirements for certain enrollees, and change the state-level funding structure.[xxviii]

Shift to Managed Care

Under the proposed NHGAHCP, enrollees would choose coverage from the MCOs and no longer participate in the PAP.

The MCO contracts with the state would be required to include cost transparency measures, ensure patients are utilizing the most appropriate level of care, offer cash and other incentives to enrollees to choose the lowest cost medical providers, set maximum payable amounts for certain medical procedures, and assist enrollees who are over the income limitations with applying for coverage in the individual insurance marketplace while maintaining care and coverage while the application is pending. To avoid loss of coverage during the transition period from the PAP to a MCO, which is required to be at least 90 days, no individual would be permitted to lose coverage solely because of the transition and MCOs would be required to honor pre-existing care plans and treatments for that transition period.

The State Senate’s proposal highlights specific areas for potential cost savings under the MCO contracts, including shared incentive pools, differential capitation rates, improving use of emergency departments, reducing preventable admissions and short-term readmissions, timely follow-up after a mental illness or substance use disorder visit, and improvements around prenatal care and neonatal abstinence births. The MCOs would be required to arrange a wellness visit for enrollees with a primary care provider that would include assessments of both physical and mental health. The MCOs would also be required to promote personal responsibility through incentives and case management.

Changes in Reimbursement Rates

The State Senate’s proposal would require the DHHS to establish behavioral health reimbursement rates for providers “sufficient to ensure access to, and provider capacity for all behavioral health services” and potentially establishing specific rates for substance use disorder services. The proposal identifies this step as a method to combat the opioid and heroin crisis. The proposal does not provide details, definitions, or a quantified minimum rate increase, nor does it specifically appropriate funding to support these increased rates.

Work Requirements for Certain Enrollees

Certain NHGAHCP enrollees would be required to engage in at least 100 hours per month of a qualifying work or other community engagement activity. Qualifying activities under the State Senate’s proposal include:

- Unsubsidized or subsidized employment in the private or public sectors

- On-the-job training

- Job skills training related to employment, with academic credit hours earned from an accredited college or university in New Hampshire, or, in the case of an enrollee who has not received a high school diploma or equivalent, education directly related to employment

- Vocational educational training not to exceed 12 months

- Attendance at secondary school or studies leading to an equivalent certificate for recipients who have not completed secondary school or the equivalent

- Job search or job readiness assistance, including engaging in certain services offered through the New Hampshire Department of Employment Security

- Participation in substance use disorder treatment

- Community service or public service

- Caregiver services for a nondependent relative or other person with a disabling medical or developmental condition

Enrollees exempt from the work requirements under the State Senate’s proposal are those who do not qualify as able-bodied adults under the federal Social Security Act, pregnant women, parents or caretakers with dependent children under 13 years of age or any child with developmental disabilities living with the parent or caretaker, and drug court participants. Certain enrollees with a disability or identified as medically frail, those with certification from a recognized health professional of their own or a dependent’s illness or incapacity, and those who are already compliant with the employment initiatives under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families would also be exempt.[xxix]

For generally nonexempt enrollees, situation-specific good cause exemptions for failing to meet the work requirement would be set forth by the DHHS in rules and must include the birth or death of a family member living with the beneficiary, severe inclement weather or natural disaster preventing completion of the work requirements, family emergency or life-changing event such as divorce, or being the victim of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking.

Notably, the State Budget for SFYs 2018-2019 includes work requirements for NHHPP enrollees that are structured differently than those in the State Senate’s proposal. The work requirements in the State Budget were drafted before the federal government had approved any Medicaid work requirement waivers for other states.[xxx]

Savings generated as a result of individuals being disenrolled from the NHGAHCP for failing to meet the work or community engagement requirements would not, under the State Senate’s proposal, be used in calculations to show budget neutrality for any federal waivers.

The State Senate’s proposal also includes an asset test for eligibility that would take effect if allowed following a future change in federal law. The asset test would set a threshold of $25,000 and exempts the individual’s home, furniture, and one vehicle from the threshold calculation.

Granite Workforce Pilot Program

Attached to the provisions directly affecting New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program, the State Senate’s proposal would establish the Granite Workforce pilot program, which was discussed as a potential component of several pieces of legislation during the 2017 Session. Funded separately from Medicaid expansion, this pilot program would expend no more than $3 million of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families grant dollars through the end of SFY 2019 to subsidize employers hiring eligible program participants. The employers would receive a $2,000 subsidy from the New Hampshire Department of Employment Security once the hire is verified and another $2,000 after at least three full months of verified participant employment.

Eligible individuals must be in a household with incomes of 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline or less and be parents aged 18 through 64 years with children under 18 years old, or a childless adult aged 18 through 24 years. No cash assistance would be provided to these adults though this program. Referral for services to reduce barriers to employment, such as transportation, child care, substance use, mental health, or domestic violence, shall be made by the New Hampshire Department of Employment Security; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds may be used to pay for these services that eliminate barriers to work in accordance with federal guidelines. Individuals shall also be referred to additional education and training opportunities based on a needs assessment and guided to priority employment areas identified in the proposal, including health care, manufacturing, construction, information technology, and hospitality. Certain outcome measurements for the Granite Workforce program would be required in a report by December 2019.

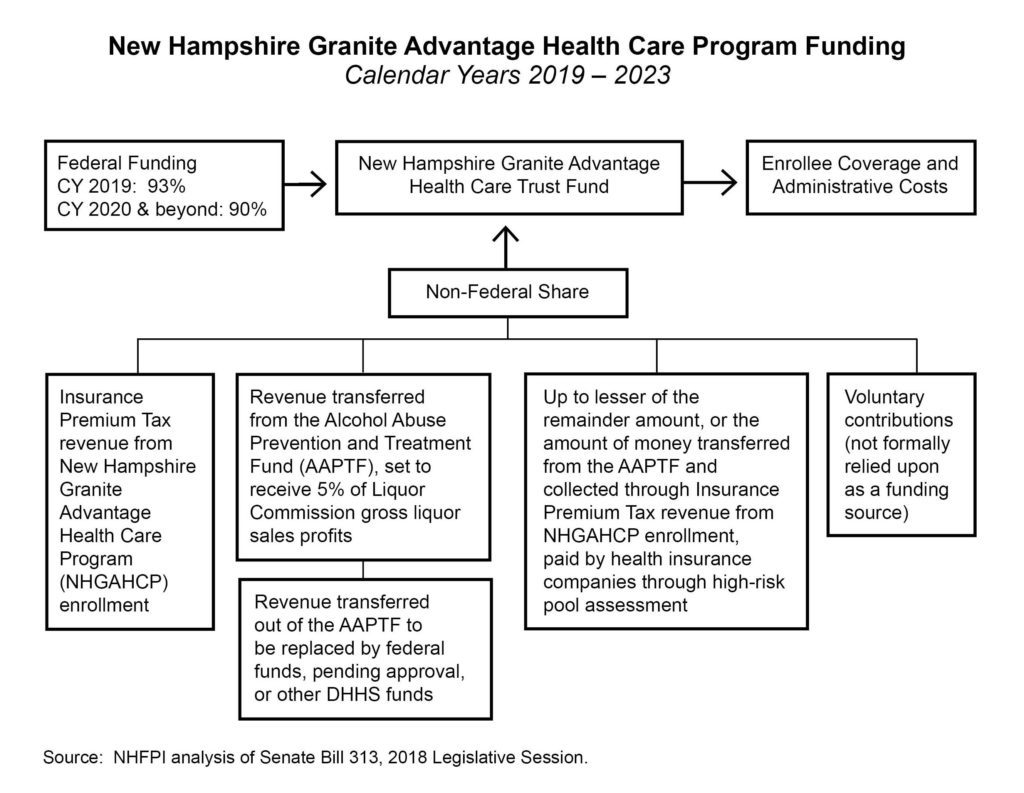

Funding the Non-Federal Share

The State Senate’s proposal makes several important changes to the mechanisms funding the non-federal share of the NHGAHCP. It retains the use of Insurance Premium Tax revenues attributable to new enrollees through Medicaid expansion as a funding source, but that source is not expected to generate enough revenue to support the non-federal share on its own. Starting in 2020, the federal share is 90 percent of the program’s cost. One official estimate indicates Insurance Premium Tax revenue would cover about 2 percent of the NHGAHCP costs in 2020, leaving a remaining 8 percent of the total NHGAHCP dollar value for the non-federal share.[xxxi]

The proposal adds a new funding source, which is money from the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund (AAPTF). The AAPTF currently receives 3.4 percent of gross Liquor Commission profits derived from the sale of liquor, raised from 1.7 percent in SFY 2017, with the remainder of Liquor Commission profits supporting the General Fund. The AAPTF share of liquor sales profits would increase to 5 percent under the proposal, and those funds would be transferred from the AAPTF to the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Trust Fund (GAHCTF). The proposal states this transfer to the GAHCTF would be used for ensuring substance use disorder and other behavioral health services delivery through the NHGAHCP, but requires that existing programs and services already approved for funding through the AAPTF would be supported through federal funding or other resources available within the DHHS. Federal fund use would require federal approval, which is not certain.

To fund the NHGAHCP for the first six months of operation in 2019, the State Senate’s proposal requires the transfer of $5.1 million from the AAPTF to the GAHCTF by December 2018. For context, the Liquor Commission transferred $3.3 million to the AAPTF from SFY 2017 profits, under the previous requirement that 1.7 percent of Liquor Commission profits be transferred to the AAPTF; 5 percent of Liquor Commission gross profits from liquor would have totaled $10.0 million. The State Senate’s proposal requires a $5 million deposit in the AAPTF by November 30, 2018, to then be moved to support the GAHCTF.[xxxii]

The NHGAHCP as proposed would continue to use the assessment on health insurance companies associated with collecting revenue to support a high-risk pool. While the NHHPP as currently established requires this assessment on health insurance companies to cover up to 50 percent of the non-federal share uncovered by Insurance Premium Tax revenues from enrollees, the State Senate’s proposal would require the assessment to cover the lesser of two amounts:

- the remainder amount, which is the total cost of the program, including administrative expenses, minus the federal share (90 percent of the service expenditures starting in 2020 and 93 percent in 2019), the contributions from the AAPTF, and Insurance Premium Tax revenues attributable to enrollees; or

- the sum of the revenues transferred from the AAPTF and attributable to new enrollees under the Insurance Premium Tax.

This arrangement may require the revenues from the Insurance Premium Tax and the AAPTF to equal half of the non-federal share or more, as a total of less than half of the non-federal share may result in these three funding sources not covering the full non-federal share. Both the AAPTF and the GAHCTF are permitted to accept gifts, grants, donations, or other money from any source.

If at any time federal funding falls below 93 percent in 2019 or 90 percent in 2020 and any following year, or if the DHHS determines as part of a regularized six-month review of funding sufficiency that a shortfall exists, the DHHS would be required to terminate the NHGAHCP in accordance with federal terms and conditions.

The State Senate’s proposal requires the DHHS to apply for necessary waivers to reduce or eliminate the non-federal share payments if the federal government permits other states to have solely federally-funded Medicaid expansion programs or use savings within the Medicaid programs to pay for the non-federal share.

Federal Waivers and Severability

Several sections of the State Senate’s proposal would likely require waivers from the federal government regarding existing sections of federal Medicaid law. Sections that specifically call for a waiver or are specifically contingent upon allowance under federal law and agreements include those related to the work requirements and the asset test, as well as certain situations that would trigger an end to the program. The State Senate’s proposal includes a severability clause, which would permit other sections of law to go forward even if specific sections are held invalid.

Evaluation Commission

The State Senate’s proposal would establish the Commission to Evaluate the Effectiveness and Future of the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program. The Commission would be similar to the PAP Commission, tasked with evaluating potential future program modifications, and be required to make an interim report by December 2020 and a final report by December 2022. Additionally, the Commission would be required to make a recommendation by February 2019 regarding monitoring and evaluation requirements for the work and community engagement requirements, including potential metrics for quarterly and annual reporting.

Fiscal Considerations Going Forward

In addition to the plethora of factors lawmakers must consider related to continuing Medicaid expansion in New Hampshire, including its value in combating the substance use disorder crisis and providing access to coverage for low-wage workers and parents who may not be able to access or afford insurance through other means, continuing Medicaid expansion is a fiscal and economic policy decision.

Non-Federal Share Funding

The State Senate’s proposal uses three sources of funding to support the non-federal share of the NHGAHCP, with donations comprising a potential fourth source. As a percentage of total costs, the non-federal share stays fixed at 10 percent in the years 2020 and beyond according to existing federal law, so the federal government will continue to pay nine out of every ten dollars used to pay for enrollee service expenditures. As health care costs increase, the non-federal share must increase as well. The overall dollar value of the NHGAHCP will likely fluctuate with enrollment; an improving economy may lead to enrollment declines, as individuals exceed the income threshold, while a worsening economy may have the opposite effect.

The funding sources identified in the State Senate’s proposal respond differently to potential changes. Insurance Premium Tax contributions would likely increase with NHGAHCP enrollment increases. Liquor Commission profits may change with the economy, but may not change in the same direction or magnitude as enrollment. Other needs that could be funded through the AAPTF may also change. The high-risk pool assessment amount is established based on predicted funding needs and adjusted annually.[xxxiii]

Potential General Fund Savings

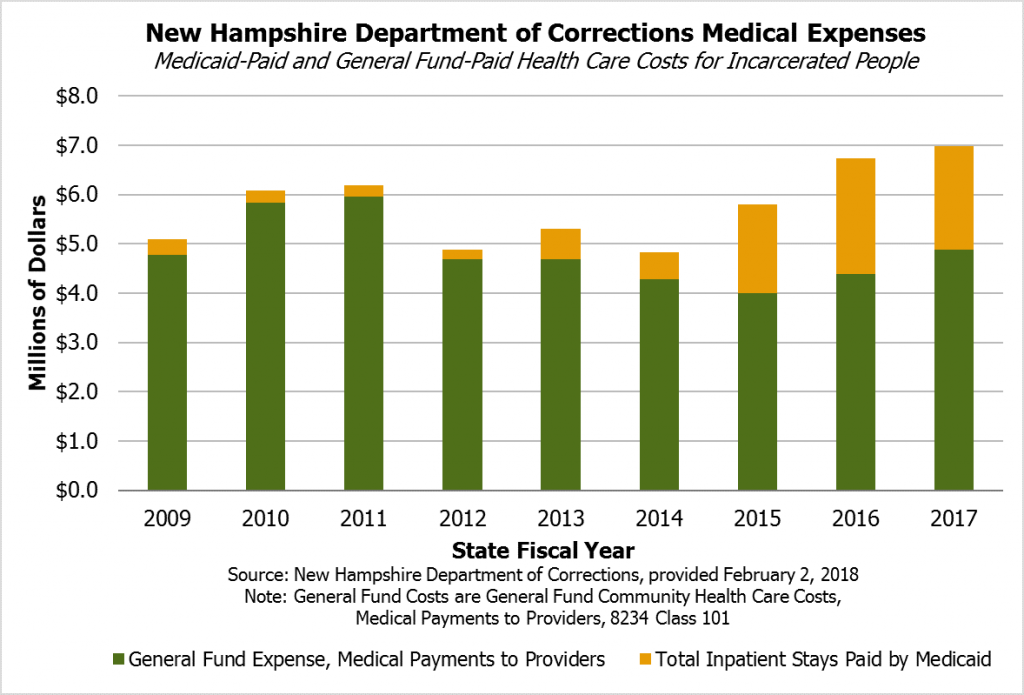

Continuing the Medicaid expansion program likely decreases costs in certain areas of the State Budget relative to not having a Medicaid expansion program. The New Hampshire Department of Corrections is one example. A larger percentage of health care payments for incarcerated individuals has been paid through the Medicaid program since SFY 2015, whereas the Medicaid program played a small role relative to the Department’s General Fund community health care expenditures in prior years. This increase, which may offset General Fund costs that would have been incurred by the Department of Corrections, coincides with the expansion of Medicaid.[xxxiv]

Expanding the MCO-served population by shifting PAP enrollees to the MCOs may also attract more competition, potentially increasing the number of MCOs contracting with the state from two to three. This change may lead to different levels of state expenditure if increased competition reduces contract costs relative to where MCO Medicaid contract costs would have been with a continuation of the PAP.

Hospitals may experience an increase in uncompensated care costs under the State Senate’s proposal, as the shift to MCOs would very likely result in lower reimbursement rates for services than under the existing PAP. These higher uncompensated care costs may increase the state’s disproportionate share hospital payments, but those increased payments in the near-term would likely not be made directly with General Funds; while they may increase future General Fund obligations indirectly through offset costs, the actual payments resulting from a near-term increase would likely be made with revenue generated through the Medicaid Enhancement Tax.[xxxv]

Experiences from other states and national studies provide examples of likely areas of New Hampshire General Fund savings. However, savings in another state, or lack thereof, do not necessarily indicate New Hampshire would have the same experience with an expiration or alteration of Medicaid expansion. General funds include different sets of services and expenditures in different states.[xxxvi]

- A report by the Louisiana Department of Health indicated Louisiana’s Medicaid expansion, which enrolled over 433,000 adults as of June 2017, saved the State $199 million in Fiscal Year 2017, and savings were projected to grow in Fiscal Year 2018. The report indicated savings to Louisiana’s General Fund stemmed from additional premium tax revenue on MCOs, some Medicaid populations that were covered under the higher state share match were covered under Medicaid expansion with the higher federal percentage contribution, lower disproportionate share payments to hospitals with a lower uninsured population and less uncompensated care, lower supplemental payments to hospitals associated with match rates, and inpatient hospital savings because newly released prisoners were eligible for Medicaid expansion.[xxxvii]

- Researchers affiliated with the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana reported, in March 2018, that Medicaid expansion in Montana, which provided insurance to over 91,000 people in January 2018, had a positive fiscal impact on the state budget due to reductions in state spending and higher revenues from increased economic activity generated by the infusion of federal dollars to the Montana health care industry. Reductions in state spending occurred in the non-expansion portion of the Medicaid program (approximately $40 million from January 2016 to the study’s reporting) and reduced spending on health care for inmates ($7.66 million in savings in Fiscal Year 2017); the study identified potential savings related to substance use disorders, mental health, and uncompensated care payments to hospitals, but did not identify specific figures. Budgetary savings were not projected to meet costs in 2019 and 2020, according to the study, but additional revenues from increased economic activity were projected to more than offset the remainder.[xxxviii]

- Michigan’s expanded Medicaid program, which covered about 600,000 residents in 2016, is required to sunset if annual state savings and other non-federal net savings are not sufficient to cover the costs of the program. Researchers for the Michigan House of Representatives House Fiscal Agency found that expanded Medicaid offset a total of $235 million in costs that would have been funded through state funds, including non-Medicaid mental health funding and prisoner health care costs as well as increased revenues from insurer and provider assessments; the House Fiscal Agency also projected a net budgetary savings through Fiscal Year 2020 to 2021 and noted additional savings may result from decreases in disproportionate share payments stemming from uncompensated care reductions and various reduced costs to local governments. Authors from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, writing for the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2017, projected that additional state tax revenue from the increased economic activity stemming from Medicaid expansion would cover almost all the 2017 state share costs and 37 percent of those costs in 2021, with the additional revenues from health plans and hospitals and state budget savings from other areas offsetting all the costs from 2017 to 2021.[xxxix]

Studies including multiple states have also found savings or limited budget impacts.[xl] A March 2016 review of 11 states and the District of Columbia by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network found states that expand Medicaid can expect to see savings from previously-eligible Medicaid populations moving to the expansion program with a higher federal reimbursement rate, a reduction in spending on programs for the uninsured, and additional revenue from existing provider or insurer taxes. This study also provides detailed tables for the 11 states showing categories of savings.[xli] A May 2017 study published in Health Affairs examined state budgets from 2010 to 2015 and found that, while Medicaid expansion was still paid for entirely by the federal government, there were no significant increases in spending from state funds resulting from the expansion or reductions in spending on education or other programs; notably, the study did not examine operations beyond the Medicaid programs in states.[xlii] The National Association of State Budget Officers also surveyed state officials in Spring 2017 and found that about two-thirds of Medicaid expansion states experienced savings in uncompensated care expenses, and half reported savings in behavioral health and corrections programs. States also reported savings in general assistance programs, other areas of health programs, and additional tax revenues from premium taxes and expanding economies.[xliii]

Federal Dollars in the State Economy

Federal contributions through the expanded Medicaid program to New Hampshire’s ability to provide services, and generally to the state’s economy, are substantial. The State received $202.4 million in SFY 2015, as the NHHPP was starting, and $406.3 million in SFY 2016 in federal funds to provide health coverage.[xliv] Some states, such as Michigan and Montana (see above), that have expanded Medicaid have experienced an overall positive impact on their state economies from the influx of federal funds.[xlv]

Shifting from the PAP, which generally has higher reimbursement rates than traditional Medicaid, to MCO services would likely reduce payments to providers in the state. This reduction may decrease the size of the non-federal share relative to the amount it would have been under PAP, and would likely reduce the amount of federal dollars coming to the state to pay for services and contribute to the state’s economy. This reduction may be as high as $200 million.[xlvi] Ending the Medicaid expansion program would potentially reduce the amount of federal funding by more than $400 million, relative to estimated payments for calendar year 2018 and based on reported SFYs 2016 and 2017 payments.[xlvii] There would also likely be negative economic effects associated with more than 50,000 people losing health coverage, which would diminish their abilities to address health conditions and remain able to participate in the workforce or care for family members.

Reauthorizing Medicaid expansion provides an opportunity to continue bringing additional federal resources to the state. Continuation of the program would help ensure more federal tax dollars return to New Hampshire to support a healthy population and a strong economy in the state.

Conclusion

New Hampshire’s Medicaid expansion program helps around 52,000 low-income adults access medical care, making it an important program for both the health of a population with limited resources and for supporting the state’s economy. The program has delivered more than $400 million in federal funds to the state in each of the last two state fiscal years, and it has played an important role in ensuring health access in communities across the state. Medicaid expansion enables individuals to receive preventative screenings and primary care as well as behavioral health and substance use disorder treatment and services, which are an essential component of the state’s efforts to combat the opioid crisis. Extending the program would ensure federal dollars would continue to flow to New Hampshire’s economy and support the state’s workforce.

Important policy questions remain regarding funding for the non-federal share, provider reimbursement rates, enrollee transitions to the individual market under proposed reforms, and various federal permissions for certain state-level initiatives. Proposed work requirements may cause some Medicaid expansion beneficiaries to lose access to the care that enables them to address their health needs. Some may have trouble meeting the necessary hours due to barriers such as transportation, while others may have difficulty with verification processes.

As policymakers continue to carefully consider reauthorization of New Hampshire’s Medicaid expansion program, they should examine these issues while determining the best policies to help ensure optimal outcomes for all New Hampshire’s residents.

Appendix

The data presented below, provided by the DHHS, represent the benefits disbursed through the NHHPP on a municipal basis. The columns show the number of residents enrolled (referred to as members) in the NHHPP by municipality as of August 1, 2017, the sum total number of months unique individuals were enrolled in the program by municipality during SFY 2017, and the number of dollars expended through the NHHPP during SFY 2017 in service expenditure payments or health plan premiums paid by municipality based on member addresses.[xlviii] SFY 2017 encompasses the second half of calendar year 2016, during which the federal government paid for 100 percent of the NHHPP service expenditures (including PAP payments), and the first half of calendar year 2017, during which the federal government paid 95 percent of NHHPP enrollee costs.

The dollar values in the Payments column do not necessarily represent dollars expended within the boundaries of the municipality itself for services, but show the number of dollars used to provide these enrollees with services. For example, if an individual whose address is in Francestown were to receive care in a hospital in Nashua, the dollars would appear under Francestown in this table; the service expenditures may have taken place in Nashua, but the benefits were tied to a person who lives in Francestown. If the dollars reflect payments for health plans, it is the health plan premium payment for enrollees by their address municipality. These figures include administrative costs built into the health plan premiums but not overall NHHPP administration costs. These figures are also subject to revision following future adjustments to payments and include both the federal and non-federal shares, with all expenditures covered at least 95 percent by the federal government during this time period. Note these dollar figures are indicative of past payments and not projected payments under the State Senate proposal.[xlix]

To view the distribution of NHHPP enrollees and expenditures by municipality, see the Appendix in the PDF version of this Issue Brief.

Endnotes

[i] See State of New Hampshire (Treasury Department), Information Statement, March 2017, page 50.

[ii] For more on New Hampshire’s Medicaid waivers, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Office of Medicaid Services presentation to the Senate Finance Committee on May 1, 2017. For more on the populations served by Medicaid in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s Common Cents posts Medicaid Assists More Than 185,000 New Hampshire Residents, July 25, 2017; Demographic Changes Likely to Increase Demand for Medicaid, August 3, 2017; and Medicaid to Schools: A Small Aspect of Medicaid but an Immense Resource for NH Schools, August 14, 2017. For more on Medicaid in New Hampshire, see the University of New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice, “NH Medicaid Today and Tomorrow: Focusing on Value,” May 31, 2017. For more on Medicaid generally, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid, August 16, 2016.

[iii] See State of New Hampshire (Treasury Department), Information Statement, December 6, 2017, page 44, and from The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Understanding How States Access the ACA Enhanced Medicaid Match Rates, September 29, 2014, and Medicaid Financing: An Overview of the Federal Medicaid Matching Rate (FMAP), September 2012.

[iv] For more on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, see The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of the Affordable Care Act, April 25, 2013, and La Follette Policy Report, “U.S. Health-Care Reform: A Primer and an Assessment,” Spring 2011. For more on federal poverty guidelines, thresholds, and levels, see Poverty Guidelines from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Note that the federal poverty guideline threshold of 138 percent is the 133 percent set in the Affordable Care Act combined with a 5 percent income disregard in the Medicaid coverage calculation.

[v] See Chapter 3, Laws of 2014 and docket for Senate Bill 413 of the 2014 Session. See also The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Fact Sheet: Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire, March 2015, and Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision (updated January 16, 2018). See also the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment and Program Characteristics, Winter 2016, page 11.

[vi] Medicaid expansion repeals were written into law in Chapter 3, Laws of 2014 and Chapter 13, Laws of 2016.

[vii] For Medicaid enrollee counts, see the DHHS New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography (February 2018), March 2, 2018. Population estimates for New Hampshire used were from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 Population Estimates.

[viii] Provided in an email from the DHHS on November 28, 2017. As of December 1, 2016, 107,430 unique individuals had been enrolled in the NHHPP at one point in time; see the DHHS presentation on the Premium Assistance Program (PAP) dated December 12, 2016. In testimony to the New Hampshire House Health, Human Services, and Elderly Affairs Committee on March 20, 2018, the DHHS Commissioner reported about 130,000 people have benefitted from the program since its inception.

[ix] To calculate the income levels required for eligibility, see the income levels and savings calculator on HealthCare.gov. For more on New Hampshire Health Protection Program (NHHPP) enrollment criteria, see the DHHS December 12, 2016 presentation on the Premium Assistance Program and the May 1, 2017 presentation on the Office of Medicaid Services.

[x] See the DHHS Premium Assistance Program web page, as well as the DHHS’s Frequently Asked Questions for NHHPP Premium Assistance Program and Important Information About the Premium Assistance Program documents, both from September 2015.

[xi] More information on the services under the NHHPP for those who are medically frail can be found in the DHHS’s Frequently Asked Questions for NHHPP Premium Assistance Program and Important Information About the Premium Assistance Program documents as well as the DHHS’s Premium Assistance and the Medically Frail, May 1, 2017 Office of Medicaid Services, and December 12, 2016 Premium Assistance Program presentations.

[xii] For more information, see the DHHS’s Health Insurance Premium Payment Program web page. See also Chapter 3, Laws of 2014 and RSA 126-A:5.

[xiii] DHHS data on the poverty status of enrollees is from the New Hampshire Health Protection Program presentation dated August 28, 2017. For NHHPP enrollment data, see the DHHS NH Health Protection Enrollment Demographic Reports.

[xiv] For DHHS data on enrollment continuity, see the Office of Medicaid Services presentation to the Senate Finance Committee on May 1, 2017. Draft data indicating reasons for leaving the NHHPP may be reviewed in the DHHS Office of Medicaid Services presentation to the Senate Finance Committee on May 1, 2017. For federal projections of enrollment churn based on proposed changes to the Medicaid expansion program, see the Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate: American Health Care Act, March 13, 2017, page 10.

[xv] DHHS geographic data by county, city, or town is available in table or map form. For information on required copayments, see the December 12, 2016 DHHS presentation on the NHHPP and RSA 126-A:5, XXX (b).

[xvi] See the DHHS presentation on the New Hampshire Health Protection Program, September 27, 2017.

[xvii] Data presented to the HB 1696 Commission to Evaluate the Effectiveness and Future of the Premium Assistance Program (PAP Commission). See similar data covering a different period presented to the PAP Commission by the New Hampshire Hospital Association, New Hampshire Acute Care Hospitals Coverage Expansion Summary.

[xviii] See The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of the Affordable Care Act, April 25, 2013.

[xix] See RSAs 126-A:5-b, 126-A:5-c, 400-A:32, III(b), and 404-G. For more information about the Insurance Premium Tax, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource. To learn about the General Fund, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource.

[xx] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services July 25, 2017 letter to the New Hampshire DHHS. See also the August 14, 2017 statement from the Governor of New Hampshire following the letter.

[xxi] See Chapter 156, Laws of 2017, page 99. See also NHFPI’s Common Cents post Medicaid Expansion Work Requirements Hinge on Federal Approval from September 5, 2017. For more on the State fiscal years 2018-2019 State Budget, see NHFPI’s July 2017 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019.

[xxii] Requirements, included in RSA 126-A:5-e, II(a), are set forth in Chapter 13, Laws of 2016.

[xxiii] For the full text of the PAP Commission’s recommendations, see the PAP Commission’s Memorandum, Final Report of HB 1696, 126-A:5-e, Chapter 13:12 – Laws of 2016, November 17, 2017.

[xxiv] For more on the discussions of the Commission to Evaluate the Effectiveness and Future of the Premium Assistance Program (PAP Commission), see Memorandum, Final Report of HB 1696, 126-A:5-e, Chapter 13:12 – Laws of 2016, November 17, 2017.

[xxv] The individual health insurance marketplace in New Hampshire is comprised of three groups: 1) those in the PAP, 2) those with higher incomes than those in the PAP but still below 400 percent of the federal poverty guideline, who receive federal subsidies to purchase health insurance, and 3) those with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty guideline who do not receive subsidies to purchase insurance. See Gorman Actuarial, Inc., Individual Market and NH Premium Assistance Program 2018 Projections, 2018 Projections.

[xxvi] See PAP Commission Meeting Minutes, September 6, 2017.

[xxvii] See the PAP Commission’s Memorandum, Final Report of HB 1696, 126-A:5-e, Chapter 13:12 – Laws of 2016, November 17, 2017 and the Fiscal Note for Senate Bill 313 as Introduced.

[xxviii] To see the entire text, see Senate Bill 313 of the 2018 Session as Amended by the Senate.

[xxix] For more on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, see NHFPI’s Fact Sheet The New Hampshire Food Stamp Program.

[xxx] For more on the work requirements included in existing New Hampshire statute and pending approval from the federal government, see NHFPI’s Common Cents post Medicaid Expansion Work Requirements Hinge on Federal Approval from September 5, 2017. For more on federal guidance on Medicaid work requirements and actions in other states, see The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid and Work Requirements: New Guidance, State Waiver Details and Key Issues, January 16, 2018.

[xxxi] For more information, see the Senate Bill 313, 2018 Session as Introduced Fiscal Note.

[xxxii] See the 2017 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the New Hampshire Liquor Commission, page 6 for the State fiscal year (SFY) 2017 gross profit from liquor sales of $200.0 million. The State Senate’s proposal sets forth that half of the amount that would have been 5 percent of SFY 2017 sales must be deposited by November 30, 2018.

[xxxiii] See RSA 404-G:5-a.

[xxxiv] Information provided by the Department of Corrections via email on February 2, 2018. See also the House Bill 1696, 2016 Session as Introduced Fiscal Note.

[xxxv] Information provided by the DHHS via email in February 2018.

[xxxvi] For more on the fiscal and economic experiences of other states with Medicaid expansion, see The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review, September 25, 2017, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Medicaid Expansion Producing State Savings and Connecting Vulnerable Groups to Care, June 15, 2016. See also The Brookings Institution, “Do states regret expanding Medicaid?” March 26, 2018.

[xxxvii] See the Louisiana Department of Health, Medicaid Expansion Annual Report 2016/17.

[xxxviii] See University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research, The Economic Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Montana, March 2018.

[xxxix] See Michigan House Fiscal Agency memorandum from September 14, 2016 to the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Health and Human Services. See also The New England Journal of Medicine, “Economic Effects of Medicaid Expansion in Michigan,” February 2, 2017.

[xl] See The Brookings Institution, “Do states regret expanding Medicaid?” March 26, 2018.

[xli] See the State Health Reform Assistance Network, “States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains,” March 1, 2016.

[xlii] See Health Affairs, Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets from Increased Spending Related to Medicaid Expansion, May 2017, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities Off the Charts post “More Evidence that Medicaid Expansion Hasn’t Hurt State Budgets,” April 18, 2017.

[xliii] See The National Association of State Budget Officers, The Fiscal Survey of the States, Spring 2017, page 69.

[xliv] See State of New Hampshire (Treasury Department), Information Statement, March 2017, page 50.

[xlv] See The National Association of State Budget Officers, The Fiscal Survey of the States, Spring 2017, page 69. See also information in the “Potential General Funds Savings” section.

[xlvi] See State of New Hampshire (Treasury Department), Information Statement, March 27, 2018, page 48 and the PAP Commission’s Memorandum, Final Report of HB 1696, 126-A:5-e, Chapter 13:12 – Laws of 2016, November 17, 2017, page 53.

[xlvii] See State of New Hampshire (Treasury Department), Information Statement, December 6, 2017, page 49 and Information Statement, March 27, 2018, page 48. See also the DHHS presentation to the PAP Commission on the New Hampshire Health Protection Program presentation dated August 28, 2017.

[xlviii] For August 1, 2017 snapshot data of NHHPP enrollment, see the DHHS NH Health Protection Program (NHHPP) Enrollment by City or Town, 8/1/2017, published August 25, 2017. DHHS payment data by municipality supplied via email on March 4, 2018.

[xlix] Payment and member month data provided by the DHHS via email on March 4, 2018; data as of November 15, 2017. Towns with fewer than five average members, no members, unknown or out-of-state members are not shown. Payments are fee-for-service payments and health plan capitation payments. Out-of-state members are those who are being treated at an out-of-state facility, including those who have moved and are in the process of being confirmed as ineligible, or show a difference between mailing addresses and residence addresses; the DHHS reports this is typically about ten people. These figures are subject to revision, as they are unadjusted for any future adjustments to health plan premiums based on performance or retrospective adjustments to capitation payments based on actual costs several months after the program year ends. These DHHS data do not include $17,812,744 in NHHPP expenditures, as those expenditures were incurred by enrollees who joined the program after the first of a month; these data only show expenditures based on enrollee addresses on the first of the month.