New Hampshire’s ongoing early care and education (ECE) shortage is characterized by high tuition costs to families, low wages for ECE professionals, limited (if any) profits for providers, and adverse financial impacts for Granite State families, businesses, and economy.[1]

Data in this brief suggest that the characteristics of the Granite State’s child care shortage may not be improving, and in some cases, may be getting worse.

Child Care Tuition Remains Unaffordable to Many

Between 2022 and 2024, tuition for an infant and four-year-old in center-based care in New Hampshire averaged nearly $30,000 annually ($29,763).[2] Among families with children under 18 years old between 2019 and 2023, this equated to approximately 19.6 percent of a median-earning married couple’s income ($152,054), 40.6 percent of a median earning single father’s income ($73,233), and 60.0 percent of a median earning single mother’s income ($49,587).[3]

Many ECE Professionals Do Not Earn Living Wages

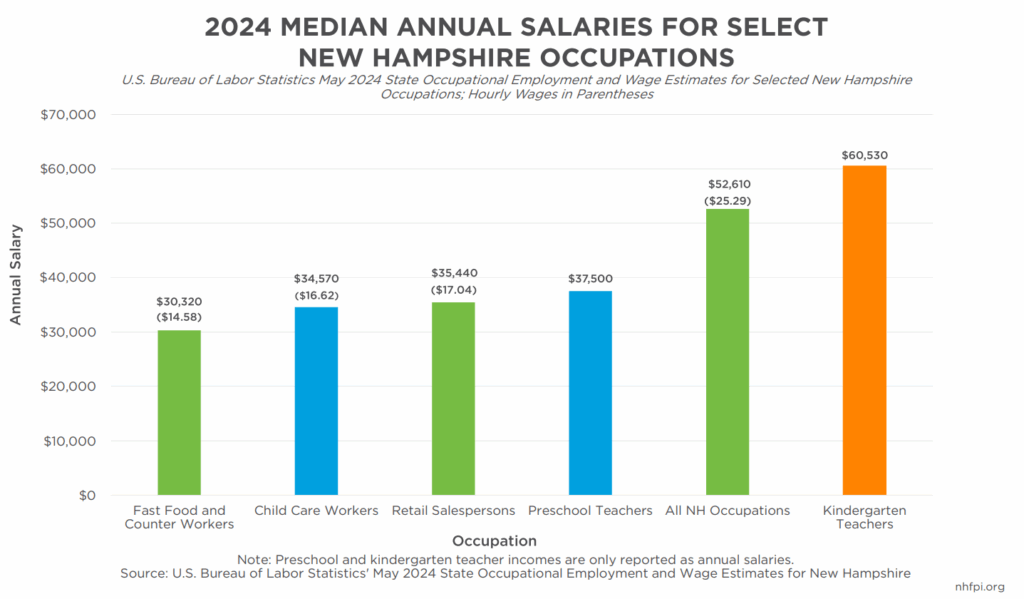

In 2024, ECE professionals categorized as “child care workers” earned a median annual salary of $34,570, over $2,000 more per year than in 2023. Hourly wages for these professionals increased to $16.62 per hour, $1.00 per hour more than in 2023.[4] Preschool teachers earned a median annual salary of $37,500, which was an estimated annual decrease of $150.00 between 2023 and 2024.[5] Completing college credits may not increase ECE professionals’ wages. Though the ECE workforce has a higher percentage of professionals with at least some college education compared to the overall New Hampshire workforce, ECE teachers with at least some college education do not earn significantly more than the overall ECE workforce.[6]

Wages for ECE professionals may be too low to meet basic living expenses in New Hampshire. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator, a single Granite State adult without children would need to earn $51,552 annually before taxes to support themselves. A single adult with one child would need to earn $93,451 while two working adults with one child would need to earn $104,373. These estimates do not include money set aside for emergency savings, retirement, or paying off student loan debt.[7]

In 2022, an estimated 9.4 percent of New Hampshire’s ECE professionals were living at or below the poverty line, compared to only 0.2 percent of elementary and middle school teaching professionals.[8] In 2021, 43 percent of ECE workforce families nationally participated in one or more public safety net programs, including the Earned Income Tax Credit, Medicaid for adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and either the Children’s Health Insurance Program or children’s Medicaid.[9]

New Hampshire's ECE Workforce Shrank Between 2023 and 2024

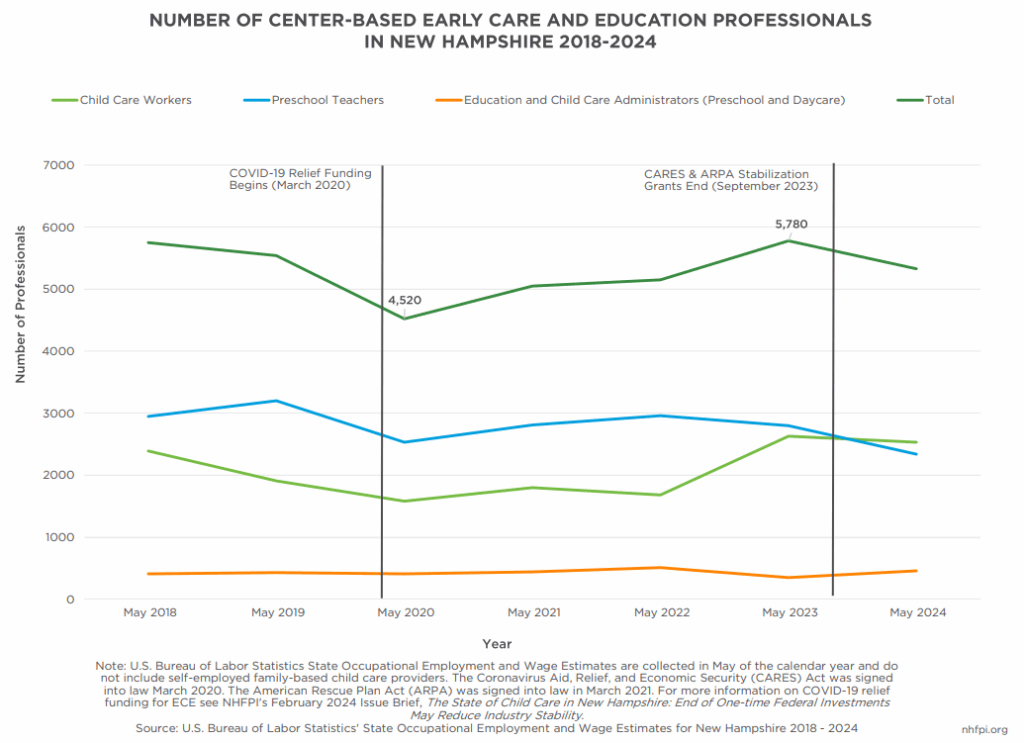

Low wages and lack of benefits may contribute to high turnover rates within the ECE profession and make recruiting new teachers difficult for providers. These challenges may have contributed to the approximately 8 percent reduction in the number of individuals employed in the New Hampshire ECE workforce between 2023 and 2024, despite the Granite State workforce experiencing a net increase of approximately 1 percent during the same period.[10] The decrease coincided with the end of several one-time COVID-19 pandemic federal aid programs including the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) stabilization grants which expired in 2023.[11] This decrease in ECE employees is based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) surveys to employers which do not include self-employed child care providers who often run family-based child care businesses from their homes. A recent analysis from the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy found Granite State family-based child care providers experienced a relatively larger closure rate between 2023 and 2024 (12.3 percent) than ECE center-based care providers (2.8 percent), suggesting the ECE workforce reduction may be larger than the BLS estimates indicate.[12]

ARPA Discretionary funds intended to support long-term stability and capacity building in the child care infrastructure, and $15 million in New Hampshire State General Funds allocated to ECE providers for recruitment and retention efforts were distributed during 2024. Potential effects from these additional funding sources are not captured in the current workforce data estimates based on allocation timelines. Future workforce data may demonstrate the full impact emergency COVID-19 funding had on the Granite State’s ECE workforce.

For more information about the impacts of ECE challenges and possible policy solutions, see NHFPI’s February Issue Brief, “The Economic Impact of the Granite State’s Child Care Shortage.”

Endnotes

[1] See NHFPI Issue Briefs The State of Child Care in New Hampshire: End of One-time Federal Investments May Reduce Industry Stability(February 2024), The Fragile Economics of the Child Care Sector (May 2024), and The Economic Impact of the Granite State’s Child Care Shortage (February 2025).

[2] Note: The average of tuition rates from 2022, 2023, and 2024 was used in these calculations because the 2024 Child Care Aware of America fact sheet for New Hampshire derived tuition averages from New Hampshire’s 2024 Child Care Market Rate Survey. The 2024 Child Care Market Rate survey had responses from about half of New Hampshire’s ECE providers and, as a result, may not have fully captured the range of possible tuition rates across the state. New Hampshire’s 2021 Child Care Market Rate survey had a final response rate of over 66 percent which is above the 65 percent response rate required by the National Center on Subsidy Innovation and Accountability to ensure representative samples and statistical validity of the survey’s results. Child Care Aware of America uses estimates and projections in years when market rate surveys are not administered. Averaging across the Child Care Aware of America estimates may provide a more accurate picture of tuition rates in New Hampshire.

[3] See U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates for Median Income in the Past 12 Months.

[4] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics for New Hampshire for May 2024 and NHFPI’s January 2025 factsheet, High Prices and Low Availability of Child Care in New Hampshire: Challenges Continue in 2025. Note: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics are employer-reported. These numbers do not capture the wages of self-employed individuals who run family child care businesses.

[5] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics for New Hampshire for May 2024.

[6] See the Carsey School of Public Policy’s September 2024 primer, New Hampshire’s Well Educated, Underpaid Child Care Workforce.

[7] See the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculation for New Hampshire.

[8] See the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment’s New Hampshire State Profile.

[9] See the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment’s Early Educator Pay & Economic Insecurity Across the States, Figure 2.2.8 Early Educator Families Participating in Public Safety Net Programs, 2021.

[10] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) Tables for New Hampshire from May 2018 to May 2024.

[11] See NHFPI’s February 2024 Issue Brief, The State of Child Care in New Hampshire: End of One-time Federal Investments May Reduce Industry Stability.

[12] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Overview and the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy and NHFPI’s Data Presentation and Discussion, slide 4.