New Hampshire’s next two-year State Budget will support services during a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The needs of New Hampshire residents may continue to be fast-changing and difficult to anticipate, as public health risks associated with the virus may be volatile during the upcoming budget biennium. Governments may have to respond rapidly to shifting conditions, particularly those agencies providing public health and economic supports. Enacted federal policies will provide significant assistance to residents and the economy in the coming months and years. However, Granite Staters with low incomes and few resources have been disproportionately impacted by the crisis, and the recovery may not fully reach those residents without additional and intentional public policy support. The services funded during the next State Budget biennium will be key for helping ensure New Hampshire’s recovery from this crisis is inclusive, equitable, and sustainable.

The State Budget proposal approved by the New Hampshire State Senate makes significant changes to the version passed by the House of Representatives. The Senate’s budget proposal, which benefitted from substantially higher revenue estimates for the biennium, restores some of the funding reductions made by the House to health and social services, including a partial restoration of funding to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services closer to the levels proposed in the Governor’s budget. The Senate voted to increase funding for nursing homes and long-term care Medicaid reimbursement rates, close the Sununu Youth Services Center in early 2023, and appropriate funding to support a 24-bed forensic psychiatric hospital. The Senate also voted to establish a voluntary family medical leave insurance program, establish an adult dental benefit in Medicaid, and provide funding for affordable housing and homeless services. The Senate’s budget would also boost funding for local public education relative to the House’s proposal, including targeting more resources to school districts with a higher percentage of students from families with low-incomes and temporarily helping school districts that saw decreases in enrollment during the pandemic.

The Senate’s budget retained the major tax reduction provisions from the House’s version of the budget. However, the budget proposal would change two key components of taxes on businesses that are projected to further reduce revenue by about $89 million beyond the nearly $158 million in estimated tax reductions included in the House budget during the biennium. Future revenue reductions would occur beyond the next State Budget biennium, as most of the proposed phaseout of the Interest and Dividends Tax would occur after the biennium ends, providing the largest tax reductions to high-income earners and reducing resources available for future State Budgets.

This Issue Brief examines key components of the New Hampshire Senate’s State Budget proposal for the next two fiscal years and focuses on changes made relative to the House’s budget proposal, incorporating comparisons to the current State Budget and to the Governor’s proposal for context in certain areas. The Issue Brief also reviews revenue projections and proposed changes to State tax policy contained in the Senate’s State Budget proposal. For comparisons between the Governor’s proposal and the current State Budget, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief on the Governor’s State Budget proposal. For comparisons between the Governor’s proposal and the House’s proposed State Budget, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief on the proposal from the House of Representatives.[1]

The Topline Changes

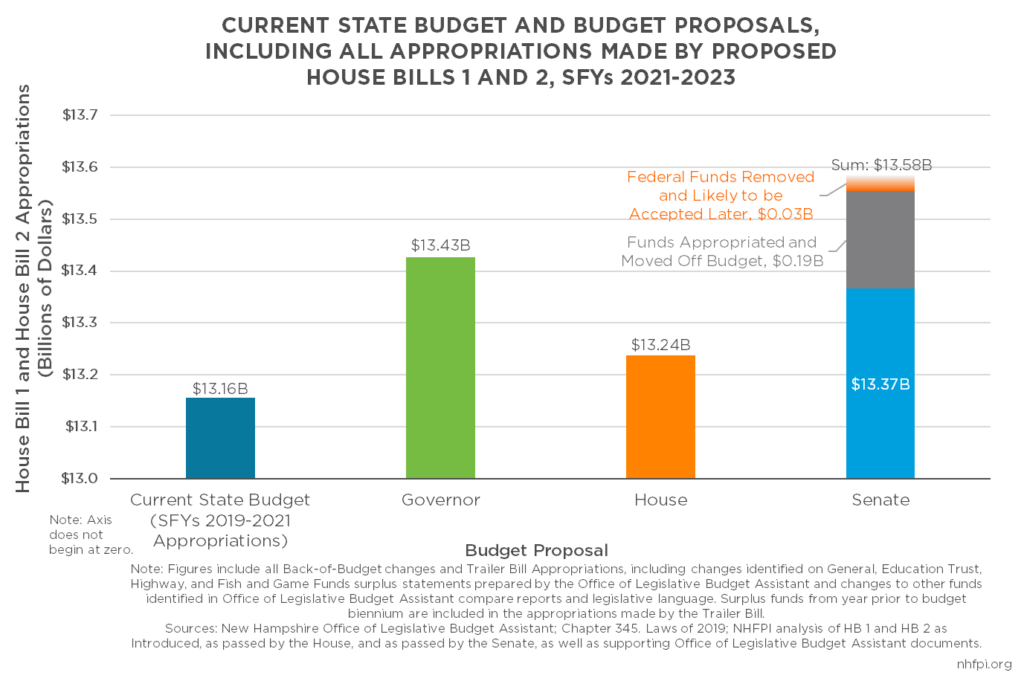

The Senate’s proposed budget for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2022 and SFY 2023, which also makes significant appropriations from the projected SFY 2021 surplus, would increase appropriations relative to the current State Budget and relative to the House’s proposal. The Senate’s budget, including appropriations made in the line items of the Operating Budget Bill, the adjustments to those appropriations made in the text of the Operating Budget Bill, and the Trailer Bill, would appropriate $13.366 billion.[2] This total is an increase, using the same calculation methods, of $209.6 million (1.6 percent) relative to the appropriations made in the last State Budget, across the two fiscal years and unadjusted for inflation.

The Senate’s budget proposal also moves $188.2 million in anticipated revenue sharing with municipalities and $30 million in federal matching funds for the Medicaid-to-Schools program out of the State Budget. For comparisons to the current State Budget and proposals from the Governor and the House, including those funds into the appropriations for the Senate’s version of the State Budget yields a total of $13.584 billion. This total is $427.8 million (3.3 percent) more than the current State Budget, without adjusting for inflation across the four-year period of the two budgets. The total is $158.0 million (1.2 percent) larger than the Governor’s proposal and $346.4 million (2.6 percent) more than the House’s version of the State Budget.

Expenditure by Category of Government Services

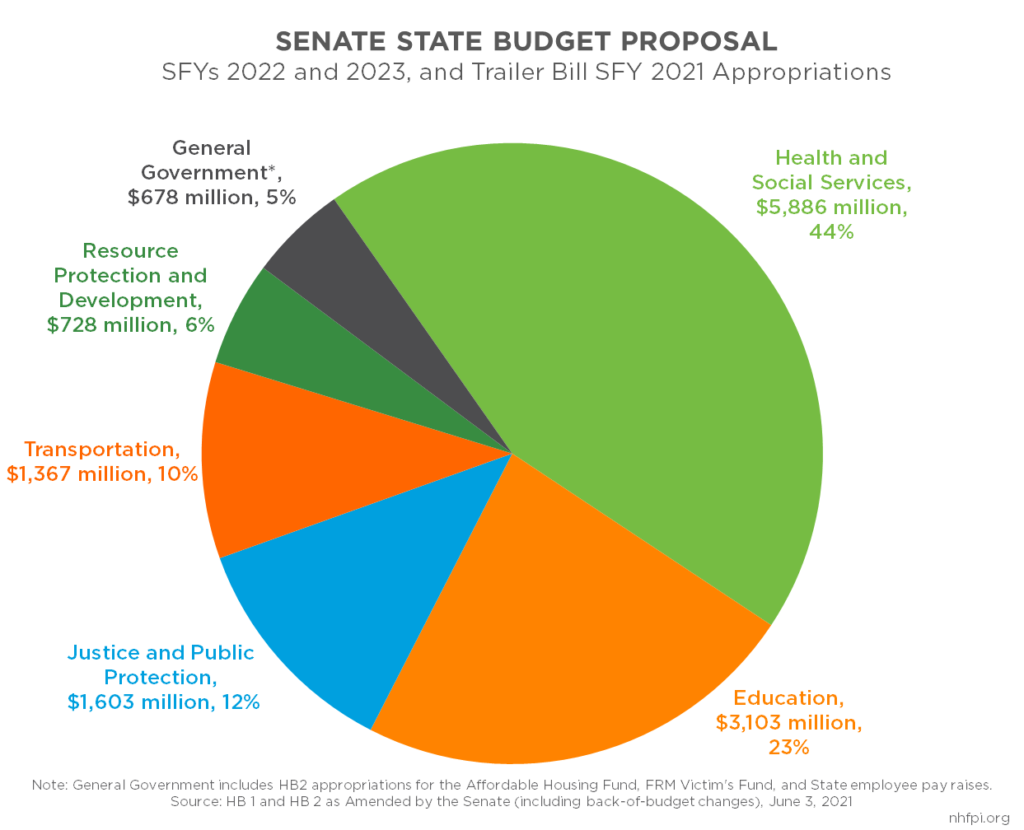

All State Budget expenditures are allocated to one of six categories based on the service area of each department. These six categories are intended to cover all areas of State government operations, and include General Government, Justice and Public Protection, Resource Protection and Development, Transportation, Health and Social Services, and Education.

The Senate’s budget proposal would, as the current State Budget does, allocate the plurality of funds to Health and Social Services, with Education receiving nearly a quarter of appropriations. Justice and Public Protection would receive the next largest appropriation, with slightly over $1.6 billion (12.0 percent) appropriated during the biennium, including General Fund and Federal Fund appropriations as well as appropriations from all other funds. Transportation would follow with $1.4 billion (10.2 percent), Resource Protection and Development with $727.5 million (5.4 percent), and General Government with $678.2 million (5.1 percent).

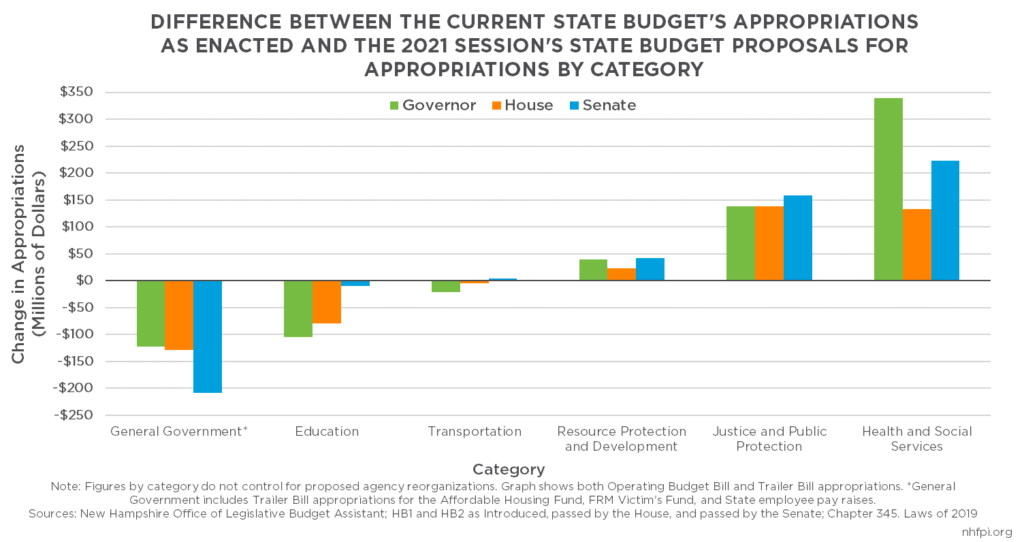

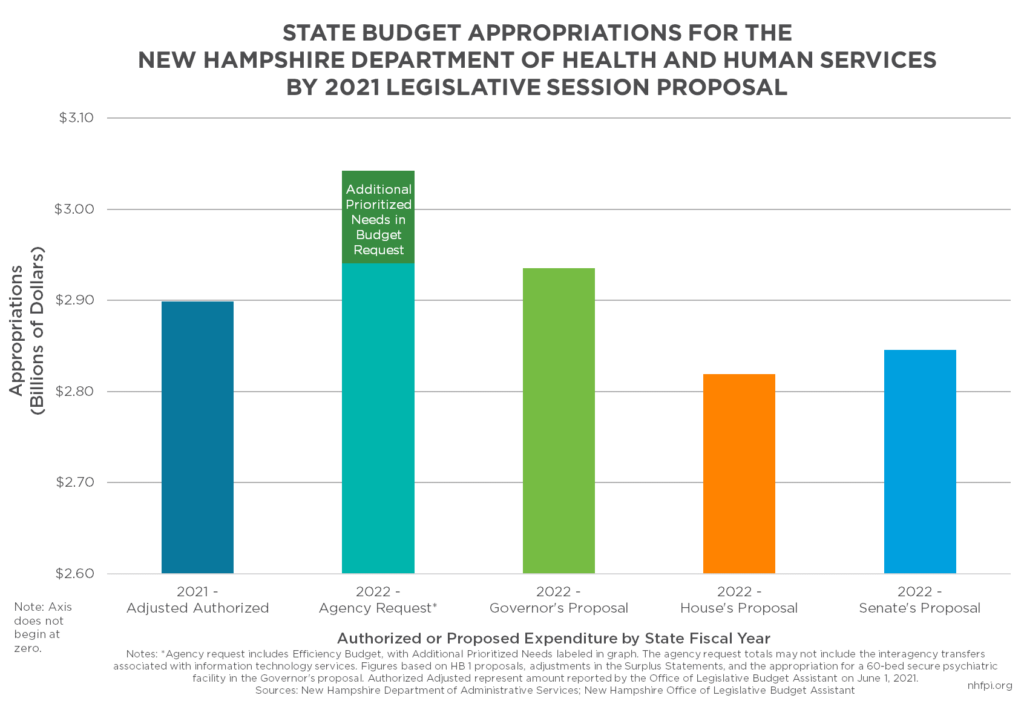

The largest dollar increases, relative to the current State Budget as passed and including Trailer Bill appropriation changes, would go to Health and Social Services, which is almost entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) budget. The Senate proposal would increase funding for Health and Social Services by $223.4 million (3.9 percent) over the current budget as enacted, less than the Governor’s proposed increase of $339.7 million but more than the House’s proposed increase of $133.0 million.

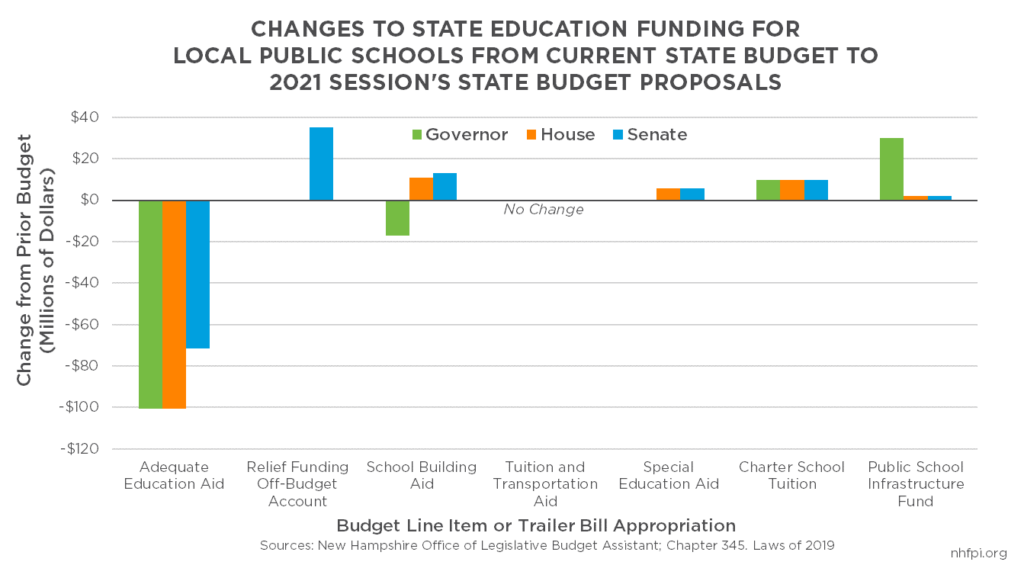

Education, the next-largest category in the State Budget, would see a lower level of funding relative to the current biennium under all three budget proposals from the 2021 Legislative Session thus far, although the decline would be smallest in the Senate’s proposal. The majority of expenditures in this category are driven by the Adequate Education Grants paid to local governments to fund public education on a per pupil basis; this category also includes funding for the University and Community College Systems, operations at the New Hampshire Department of Education, the Police Standards and Training Council, and the Lottery Commission, which generates revenue to support the Education Trust Fund. Relative to the Governor’s proposal and the House’s proposal, the Senate would add targeted aid for school districts with more students from families with low incomes and provide additional assistance to school districts that saw declines in enrollment during the pandemic. The Senate would reduce spending in the Education category by $10.0 million (0.3 percent), while the House would reduce spending by $79.4 million and the Governor would reduce appropriations by $104.3 million relative to the current State Budget in the Education category.

General Government would see the largest dollar decline relative to the current biennium in all three budget proposals to date, with the largest reduction coming in the Senate’s version of the budget. General Government appropriations would decline by $208.0 million (23.5 percent) from the current State Budget to the Senate’s proposal, while the Governor’s budget proposed a decline of $122.4 million and the House proposed a $129.1 million decline. The declines across all three budgets stem in part from one-time aid in the current budget of $40.0 million to municipalities not being repeated in the new proposals (this aid had been included in the New Hampshire Treasury Department’s budget) and reported one-time savings in State retiree health insurance benefits. The larger decline in the Senate is due to an estimated $188.2 million in expanded revenue sharing with municipalities being moved to a special, dedicated fund that would not be included in the State Budget.

Changes in appropriations associated with the creation of the Department of Energy, a proposal altered but largely retained by the Senate, and assigning court security reimbursement responsibility and funding to the Judicial Branch shift allocations from General Government to Justice and Public Protection relative to the current State Budget. Relative to the House’s proposal, Justice and Public Protection would see only a larger increase in the Senate’s proposal, with a $158.5 million (11.0 percent) increase in the Senate’s budget relative to current funding levels. The increase relative to the House is largely due to increases in funding at the Department of Safety for added positions in a variety of areas, and restoring funding for positions associated with law enforcement at the Liquor Commission that the House had eliminated.

Transportation funding would increase by $3.8 million (0.3 percent) in the Senate’s proposal, while there would be a small decline of $4.2 million in the House’s proposal and a larger decline of $21.3 million in the Governor’s version of the budget.

Resource Protection and Development funding would increase by $41.9 million (6.1 percent) in the Senate’s version of the State Budget. The primary difference relative to the House budget in this category is the Senate’s appropriation of $15.6 million in State aid grants to municipalities for water pollution control and public water systems that the House voted to remove.

Proposed Changes by State Agency

State agency-level analysis provides additional insight into the changes proposed by the Senate relative to the House’s version of the State Budget. The previous analyses comparing budget categories and funds provide comparisons between the two-year budgets proposed by the Governor, House, and Senate relative to the two-year State Budget approved by policymakers in 2019. The analysis of State agency budgets in this section compares the Senate’s budget proposal to the House’s proposal only, and does not reflect the changes proposed by the House relative to the currently-enacted State Budget.[3]

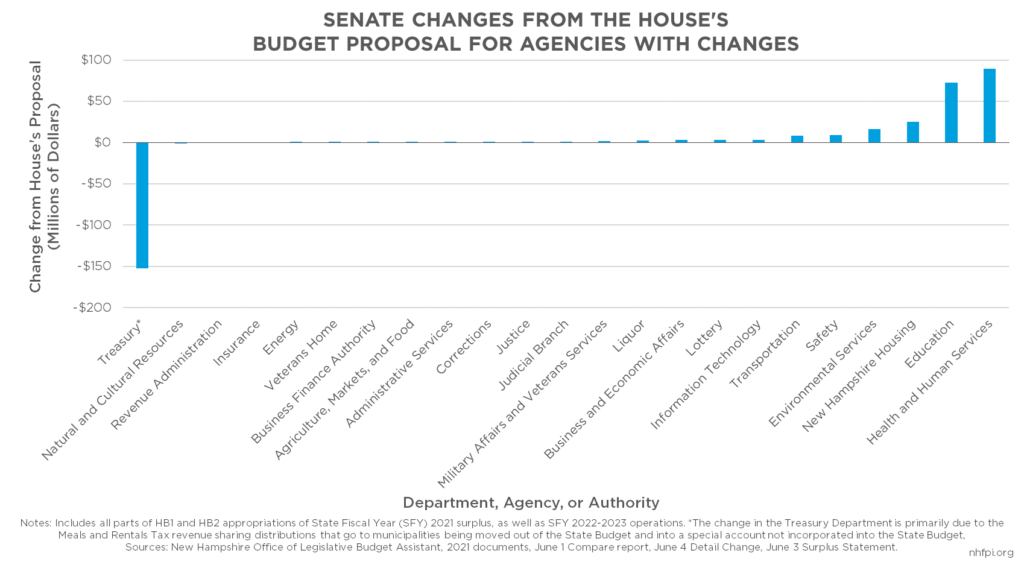

The Senate changed the House’s proposed levels of appropriations at 23 agencies, including the appropriation to the Affordable Housing Fund administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority (which is otherwise not included in the State Budget).

The largest decrease in funding proposed by the Senate relative to the House’s proposal is in the Treasury Department. As noted previously, the Senate removed approximately $188.2 million in appropriations made by policy changes in its budget proposal out of the State Budget; this change shifts approximately $152.6 million out of the State Budget that was included in the Governor’s and House’s proposal in the Treasury Department. This aid will still flow to municipalities, but will no longer be included in the State Budget.

Funding level adjustments at most other State agencies with any change in appropriations were small, and budget reductions were limited. Notable changes include the removal of two tax auditor positions at the Department of Revenue Administration that had been added by the House.

A significant amount of funding was added to the DHHS relative to the House version of the State Budget. One of the key changes the Senate made is removing the $50.0 million reduction in General Fund appropriations that the House added to the text of the Operating Budget Bill in a back-of-the-budget reduction. The Senate removed this provision, although it retained the back-of-the-budget reduction of $22.6 million in General Fund dollars that had been added by the House and that is focused on eliminating positions. The Senate also made several key appropriations to the DHHS from SFY 2021 surplus funds, including $30 million to help construct a forensic psychiatric hospital and $6 million to support more transitional housing beds and raise reimbursement rates for certain behavioral health services.

The Senate also voted to add funding to the Department of Education, including appropriations for targeted aid to local school districts. The Affordable Housing Fund, administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority, would receive a $25 million one-time appropriation under the Senate’s budget. There were also substantial increases at the Department of Environmental Services, which was an increase in grants to municipalities, the Department of Safety for more positions, and the Department of Transportation.

Agency Reorganizations

The Senate voted to retain much of the proposed creation of a Department of Energy that the Governor had introduced in his budget and the House modified. The Senate made modifications as well, but kept the basic structure of the new Department of Energy the same; the new Department would include the energy-related components currently in the Office of Strategic Initiatives, while the planning components of the Office would be shifted to the Department of Business and Economic Affairs. The Public Utilities Commission would also be administratively attached to the Department of Energy, and some of its responsibilities would be moved to the new Department.

The Senate removed the proposal to merge the University System and the Community College System. The Governor had proposed merging the two systems over the biennium, with the process beginning quickly. The House had voted to establish a study commission to examine whether a merger was the best option; if the commission decided going forward with the merger was in the best interests of New Hampshire, then the merger would have been completed by the end of the biennium. The Senate voted to remove both the language requiring the merger on a certain timeline and the study commission, with no envisioned merger in its version of the State Budget.

Health and Human Services

With the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacting the health and economic well-being of many Granite Staters, increased needs for health and social services over the next two years renders this already key area of State-supported services even more critical. The DHHS is the largest State agency and administers several critical programs, including Medicaid, the Food Stamp Program, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, all of which include significant amounts of federal funding support. Medicaid, which provided health coverage for more than 220,000 Granite Staters at the end of May 2021, totaled approximately $2.1 billion in expenditures in SFY 2020, with more than half of those expenditures funded by the federal government.[4]

The Senate’s budget proposal would increase funding to the DHHS by $89.2 million relative to the House’s budget proposal. The total funding appropriated to the DHHS by the Senate in SFY 2022 would be $53.3 million (1.8 percent) lower than the funding authorized in the DHHS SFY 2021 adjusted authorized budget.[5]

Back of the Budget Reduction for Positions

The Senate retained one of the House proposals to include a back-of-budget reduction to appropriations for the DHHS. This retained reduction focused on removing currently vacant but funded positions. The total reduction during the budget biennium would be $22.6 million in General Fund appropriations, without specifying amounts for individual budget years. The amendment would eliminate approximately 226 positions and limit the DHHS to having no more than 3,000 full-time authorized positions during the biennium. The DHHS would be required to report to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee as to which budget lines would be reduced in each September of the biennium for the reductions made in that fiscal year.

Long-term Care and Medicaid Reimbursements

The Senate made several key changes to the House version of the State Budget to support long-term care. In these budgeted increases in appropriations, the Senate avoided adding costs to counties, which are responsible for helping fund long-term care Medicaid costs for county residents.[6]

The Senate’s budget boosts Medicaid reimbursement rates for the Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver (CFI) program, which provides care to individuals in their homes or communities and is designed to be an alternative to nursing home care.[7] The Senate voted to boost most of the reimbursement rates for CFI services by five percent. Services that are market- or manually-priced would not receive an increase. Personal care services, homemaker services, case management services, and adult day medical care would receive boosts of more than five percent. Certain unspent funds from the current budget biennium would also be used to support the direct care CFI workforce with stipends, benefits, or other forms of direct compensation to staff.

The Senate would also appropriate an increase of funds to nursing homes of five percent, totaling approximately $21.4 million in both General Fund contributions and matching federal dollars, and not requiring counties to provide additional dollars; had the counties been required to contribute, those funds would have likely had to be raised from property taxes.

To help fund some of these changes, the Senate voted to make an estimated $11.0 million in appropriations from the current State Budget that have not been fully expended available for both CFI and nursing home services in SFY 2022.

The Senate voted to add a total of $4.0 million, including both State and federal funds, available for adult medical day services. Separately, the budget proposal includes a five percent Medicaid reimbursement rate increase to skilled nursing facilities and facilities providing intermediate care to people with intellectual disabilities.

The Senate also proposed establishing a committee to study reimbursement rate parity in several Medicaid waiver programs.

Closure of the Sununu Youth Services Center

The Senate’s budget proposal would close the Sununu Youth Services Center (SYSC) by March 1, 2023. The House had proposed closing the SYSC by July 1, 2022. The SYSC is a secure institutional setting for individuals under age 18 who have been court ordered to such a setting and participate in behavioral programs.[8] In recent years, the number of individuals served by SYSC has been declining to a substantially smaller number than the facility’s capacity.[9]

The Senate modified the House’s proposal, which included specific appropriations for different phases of the closure, including sums for closure, job training for State employees currently working at SYSC, and a study commission. The Senate voted to shift all appropriations for the SYSC to the Trailer Bill, making the appropriations for more general purposes, and reformed the commission into a committee with different membership. The committee would have to develop a plan for the closure and replacement of the SYSC, would have to determine the cost of a replacement facility that could serve up to 18 individual youths at a time, and would create legislation to accomplish these goals to be considered during the 2022 Legislative Session.

Child Care and Protection

In the Governor’s budget proposal, the Child Development Program in the Human Services Division also saw about $15.2 million less allocated during the Governor’s proposed budget biennium than in the current State Budget, with the reductions concentrated in employment-related child care funding. These dollars were not offset by funding increases for the same or similar services elsewhere in the budget proposal.

As the public health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis recede and more workplaces open, child care services will be critical to enabling more Granite Staters to return to work.[10] The House did not add funding for employment-related child care relative to the Governor’s proposal, but did vote to authorize the DHHS to draw funding from available Temporary Assistance to Needy Families federal funds if needed to avoid a waitlist for services. The Senate added language requiring that any additional funds required to avoid a waitlist for enrollment-based reimbursements not be drawn from the General Fund.

The Senate also added $3.0 million in State funds for child care services directed to serve families that had previously been involved with the DHHS’s Division of Children, Youth, and Families. Families who had previously been involved with preventive or protective cases, but have had their cases closed, could have their child care services supported with these funds.

The Senate budget would also fund an additional 10 child protective service worker positions at the Division of Children, Youth, and Families. The Senate’s Trailer Bill includes accompanying language expressly permitting the DHHS, if the 10 positions are all filled, to come to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee with a request to fund up to an additional 12 child protective service worker positions.

Separately, the Senate voted to approve $3.0 million in State and federal funds to support home visiting programs for Medicaid-eligible children and their families, as well as Medicaid-eligible pregnant women.

Forensic Psychiatric Hospital and Mental Health Care

The Senate appropriated $30.0 million from SFY 2021 surplus General Fund dollars to support the construction of a forensic psychiatric hospital. This allocation would add funding to the $8.75 million appropriation in the currently-enacted State Budget, set aside to construct a 24-bed facility on the grounds of New Hampshire Hospital; cost estimates for this facility have reportedly increased. This new hospital would include space for individuals currently held at the Secure Psychiatric Unit at the State prison. The Governor had proposed using $17.25 million in federal funds to build a 60-bed facility in his budget proposal, and the House had removed the appropriation for the facility entirely.

The Senate’s budget would allocate $6.0 million during the biennium, also drawing from SFY 2021 surplus funds, to support enhanced reimbursement rates for transitional housing beds and to support new transitional housing beds for forensic patients and those with complex behavioral health conditions. The DHHS could also draw on certain past appropriations from the current State Budget to fund these supports as well.

The Senate also voted to add $3.0 million for community mental health program stabilization services, and approximately $5.2 million the system of care funds to support mobile crisis response team costs and non-Medicaid payments.

Restrictions on Abortions

Although not within the purview of the DHHS or necessarily having a direct impact on State finances, the Senate voted to include restrictions on certain reproductive health care services in the Trailer Bill of the State Budget. The Senate’s State Budget would ban all abortions after 23 weeks of pregnancy, except in cases of a medical emergency that presents serious risk of substantial and irreversible impairment of major bodily function of the pregnant woman, including death. Health care providers who knowingly perform an abortion 24 weeks or later into a pregnancy would be guilty of a felony. Providers would face reporting requirements associated with performing abortions, and the language includes a severability clause that would maintain other portions of the statute if portions of the law are ruled invalid.

The Senate removed language proposed by the House that would have required family planning operations that receive State funds to be separate, both physically and financially, from certain reproductive health facilities.

Other Health and Human Services Changes

The Senate voted to make several other changes to funding and policy at the DHHS, including:

- adding a dental benefit to Medicaid for adults aged 21 years and older, beginning no later than January 2023

- creating and funding an incentive for enrollees in the Food Stamp Program, also known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), by providing a dollar-for-dollar match for SNAP beneficiaries for fresh fruits and vegetables, with an emphasis on locally grown food, at farmer’s markets, farm stands, and other food retailers

- adding $3.0 million for funding shelter programs to assist people experiencing homelessness

- funding a youth outreach program relative to tobacco use prevention and cessation

- limiting expansion of closed loop referral systems until the use of these systems and privacy concerns can be addressed by a legislative oversight committee

Local Public Education

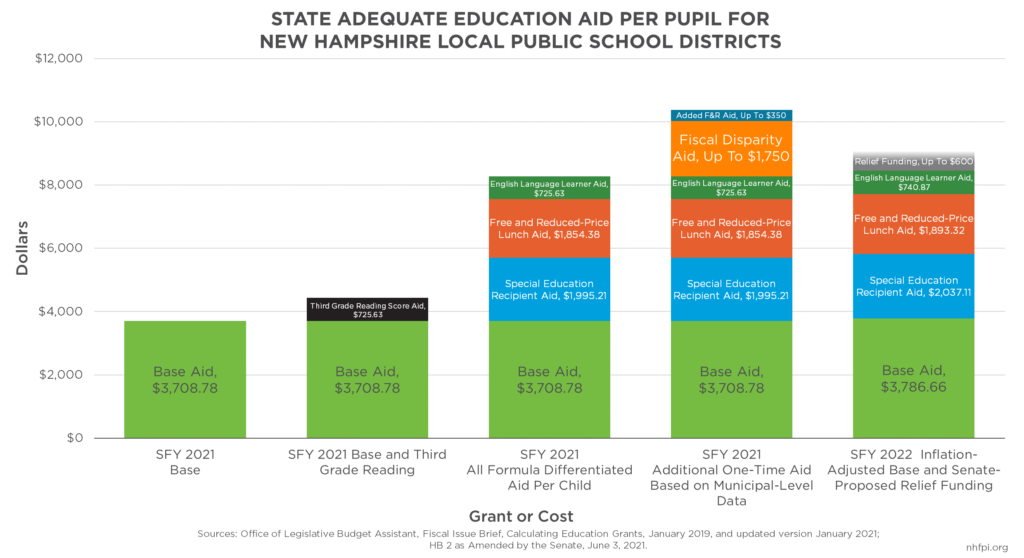

The Senate’s version of the State Budget included significant changes to funding for local public education. The Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s proposal both had significant drops in local public education funding, although the House added resources to support special education students and altered funding for school building construction. The Senate retained the lower student enrollment projections that the Governor and the House used in their versions, and also would discontinue the funding targeted at communities with lower taxable property values per student included in the current State Budget. While those changes would continue to reduce funding for local public education in aggregate in the Senate’s budget relative to the current State Budget, the Senate’s version would add significant new targeted aid funding for school districts with higher concentrations of low-income students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, and add resources for temporary adjustments to funding for districts that experienced lower enrollment during the pandemic.

Temporary Boost to Enrollment-based Aid

The Senate Finance Committee voted to limit the financial impact of the drop in enrollment in public schools on State-provided aid. The total number of pupils in New Hampshire public schools declined about 4.2 percent between the 2019-2020 school year and the 2020-2021 school year.[11] State aid to local public schools in New Hampshire is largely based on enrollment, as the Adequate Education Aid formula allocates funding on a per pupil basis.[12] This drop in enrollment, which continues a trend of declining overall enrollment but was likely substantially exacerbated by the pandemic in a temporary fashion, has the potential to reduce funding to school districts significantly if the formula is not altered.

The Senate voted to permit schools to use the higher enrollment figures of either the 2019-2020 school year, before the pandemic, or the 2020-2021 school year for determining enrollment-based State aid for the 2021-2022 school year. The Senate’s budget also includes provisions for using a modified baseline for measuring third-grade reading scores for the purposes of State education aid, and proposes policy language that would extend the enrollment-based hold-harmless policy for funding specific to free and reduced-price school meal enrollment into SFY 2023; if a federal waiver on certain enrollment-related requirements for free and reduced-price meal programs is extended, then enrollment figures could be artificially suppressed, and school districts would be able to continue relying on pre-pandemic figures for State funding under the Senate’s proposal. These enrollment-based provisions would add approximately $29.0 million in appropriations for local public schools in SFY 2022.[13]

Relief Funding

The Senate also voted to establish “Relief Funding” for school districts in addition to the baseline Adequate Education Aid funding formula. This Relief Funding would be constructed in a similar method to a component of the one-time aid in SFY 2021 under the current State Budget. The Relief Funding would target more aid to school districts with higher concentrations of free and reduced-price school meal-eligible students. These students come from families with low incomes, typically with incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or less than $40,626 for a family of three in 2021, to be eligible.[14] The additional amount of aid to school districts per student aid would be allocated on a sliding scale, and could be as high as $600 per eligible pupil for districts with more than 48 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals. Districts with less than 12 percent of students eligible for this assistance would not receive additional aid. The total appropriations are capped at $17.5 million per year in aggregate, with amounts to each individual district pro-rated to match that total, so the additional amount per student may not reach $600. The one-time aid in SFY 2021 that is similarly structured also used a sliding scale from 12 percent to 48 percent, and provided a maximum amount of additional aid of $350 per eligible student; this formula provided an additional $11.7 million in targeted aid to school districts in SFY 2021.[15]

The $35.0 million appropriation to support this Relief Funding would be shifted out of the Education Trust Fund’s SFY 2021 surplus and moved to a special account. As a result, it does not appear in the bottom-line figures for the SFY 2022-2023 budget proposal from the Senate.

School Building Aid

The Senate voted to provide an additional $30.0 million for the school building aid program. The House had appropriated an additional $27.8 million in its budget proposal, and divided the total between new projects and paying off debt from previous projects more quickly. The Senate changed the appropriation to be dedicated to funding new projects, rather than dedicating any of these funds to paying off debt. The Senate voted to draw these funds from the SFY 2021 surplus, resulting in this appropriation not appearing in the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget’s totals. The Department of Education reports there are about $104.2 million in school building aid applications for SFYs 2022 and 2023, and substantially more from applications ranging from 2011 to 2020 that have not been funded by the State.[16]

Compliance with Federal Requirements

Under the Senate’s budget, the State would be required to comply with federal maintenance of effort and equity requirements associated with school funding and required by the American Rescue Plan Act.[17] No additional funding was budgeted to maintain this compliance, which is based on funding levels from prior years and is a requirement of receiving certain federal assistance. The State Budget proposal would establish a mechanism through which the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the New Hampshire Department of Education could make adjustments during the biennium to maintain compliance.

Education Freedom Accounts

The Senate also voted to include a major shift in education funding policy to the State Budget. This policy would permit parents, who disenroll their children from school districts, to apply for and receive the Adequate Education Aid funding the school district would have received to support that student in an “Education Freedom Account.” Money in this Account could be used by parents for a wide variety of education expenses, including tuition and fees at a private school, Internet services and computer hardware primarily used for education, non-public online learning programs, tutoring, textbooks, school uniforms, certain therapies, and other expenses approved by an approved scholarship organization.

To be eligible, a student must be a state resident eligible for public school from a household with an annual household income at 300 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or below at the time of application. However, that student’s household does not need to maintain incomes below that level to continue to be enrolled and receive funding through the Education Freedom Account.

School districts would no longer receive this Adequate Education Aid, but the State would supply two years of transition funding after the student departs the district and begins receiving funding in an Education Freedom Account. Districts would receive 50 percent of the original amount for the newly-disenrolled student in the first following school year, and 25 percent in the second year. The grant would disappear after the second year following a student’s transition to using an Education Freedom Account. These transition grants would not be provided to school districts for students who disenroll after July 1, 2026.

The potential cost of this Education Freedom Account policy is difficult to project, as it is dependent on the number of currently homeschooled and private-school pupils that are eligible and apply for an Education Freedom Account as well as the number of students whose parents disenroll them from public schools and transition to use of these Accounts. The Department of Education assumes relatively low enrollment in Education Freedom Accounts during the next two years, which results in a projected cost to the Education Trust Fund of $3.45 million during the biennium.

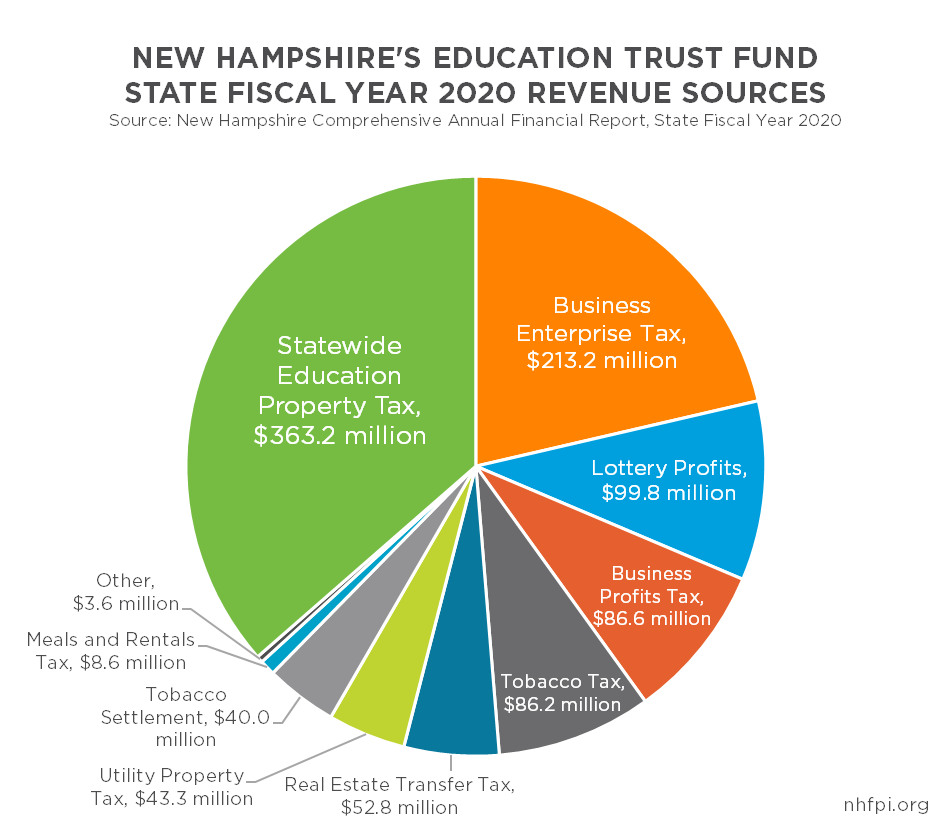

Statewide Education Property Tax Reduction and Refunds

The Senate voted to maintain the Statewide Education Property Tax (SWEPT) reduction of $100 million for SFY 2023 that had been proposed by the House. The SWEPT is a State tax that supports the Education Trust Fund. The State requires local governments to apply this property tax in their jurisdictions, based on calculations conducted by the Department of Revenue Administration, to raise money to support local public education and offset a certain portion of the State’s statutory obligation to fund local public education under the education funding formula. The State does not collect any revenue from the SWEPT; all money is raised and retained locally. The State calculates the amount to be collected by each jurisdiction based on an estimate of taxable property value statewide and the target amount to be collected statewide.[18]

While the reduction of $100 million in the targeted amount to be raised by the SWEPT is primarily a revenue source change for the Education Trust Fund, it functionally provides more resources from other Education Trust Fund revenue sources to local governments, potentially relieving upward pressure on local property taxes.

The Senate’s version of the State Budget includes a provision, carried forward from the House, that provides an estimated $15.3 million to communities that have substantial amounts of property wealth per student.[19] These are communities that generate more revenue than is needed to support the State’s Adequate Education Aid obligations when the SWEPT statewide rate is applied to their communities. Under current law, these communities can keep those excess SWEPT dollars locally, rather than paying them to the State under this tax, as long as the dollars are used to support education. The estimated $15.3 million appropriation in the Senate’s version of the State Budget would provide aid to these relatively property-wealthy communities to offset the loss of excess SWEPT revenue, which is beyond the amount obligated to these communities by the State under the Adequate Education Aid formula.

Non-Education Aid to Municipalities

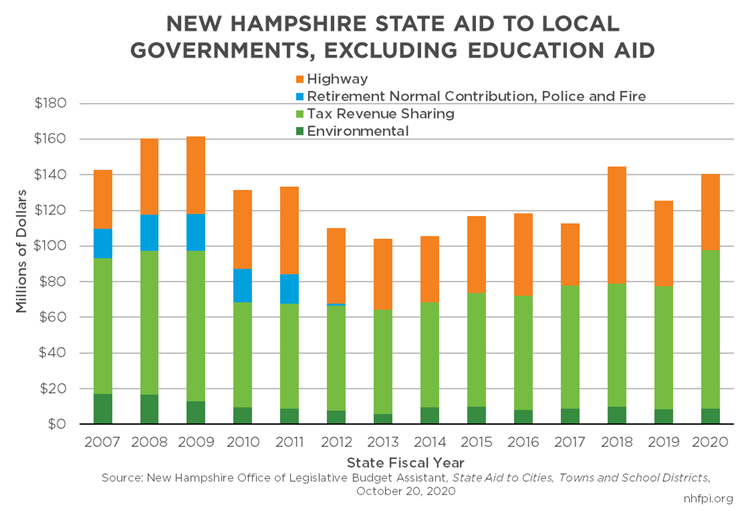

The Senate voted to substantially increase non-education aid to local governments relative to the Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s proposed increases.

The Senate voted to distribute more aid to municipal governments through the Meals and Rentals Tax revenue sharing. Current statute requires that a catch-up formula be used to eventually share 40 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax revenue with municipal governments on a per capita basis, as the State has shared much less than that 40 percent amount during the last decade. Both the Governor and the House proposed letting the catch-up formula resume, rather than suspending it, as it has been for most years since the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

The Senate voted to eliminate that catch-up formula and the 40 percent pledge, instead setting the shared amount to 30 percent and fully funding that smaller share. This change would result in approximately $35.6 million more in Meals and Rentals Tax revenue distributed to cities and towns during the biennium than the amounts budgeted by the Governor and the House, and would be approximately $50.6 million more than was distributed through this mechanism in the current State Budget.

The current State Budget included targeted one-time grants totaling $40.0 million in municipal aid through a different formula; the Senate’s proposed State Budget would not repeat those payments.

In the Senate’s State Budget proposal, all Meals and Rentals Tax revenue shared with cities and towns would be deposited into a separate fund. This change would move a total of approximately $188.2 million in expenditures that would otherwise appear in the SFYs 2022-2023 expenditures out of the State Budget entirely.

The Senate voted to use $15.6 million from SFY 2021 General Fund surplus dollars to support State aid grants for payments on existing grants for municipal water and pollution control infrastructure projects. These funds had been removed from the Operating Budget Bill in the House’s version. The Senate’s budget also added $2.4 million in grants to county and local law enforcement agencies from the Department of Safety from SFY 2021 surplus dollars.

The Senate also voted to alter State law to permit municipalities to accept funds from the federal government provided by the American Rescue Plan Act.[20]

Housing and Homelessness

The Senate voted to appropriate $25.0 million to the Affordable Housing Fund in a one-time appropriation. The Fund will receive an additional $10.0 million in the two years of the State Budget from a dedicated $5.0 million per year appropriation from the Real Estate Transfer Tax, a policy that was first established in the current State Budget. The Fund, which is administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority, provides grants and low-interest loans for building or acquiring housing affordable to people with low-to-moderate incomes. This $25.0 million appropriation would be made out of the SFY 2021 General Fund surplus, and would not appear in the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget totals as an expenditure.

The Senate also voted to boost funding for the Shelter Program at the DHHS Bureau of Homeless and Housing Services by $3.0 million in General Funds during the biennium.

The Housing Appeals Board also would receive a boost in funding relative to the House’s version of the State Budget to support the Board’s operations.

Transportation

The pandemic’s negative impacts on transportation-related revenues have been more durable than those on other key revenue sources for New Hampshire, including General Fund and Education Trust Fund revenue sources. The Governor’s budget proposal had allocated less for the Department of Transportation, as revenue streams based in part on traffic volume and dedicated to transportation expenditures were projected to be diminished. The House made significant boosts to funding at the Department of Transportation by deploying General Fund dollars for specific purposes. The Senate voted to revise those General Fund appropriations and made a significant deposit into the Highway Fund to support future solvency.

The Senate added a total of $8.1 million (0.6 percent) to the appropriations for the Department of Transportation relative to the House’s budget, bringing the total to just above the expenditures in the current State Budget. While some line-item changes were made in the Operating Budget Bill, most of these changes were made in the Trailer Bill and were for specific appropriations of General Fund dollars.

The House voted to appropriate $19.0 million in General Fund dollars to the Department of Transportation for four purposes. The House would allocate $6.0 million for purchasing fleet vehicles and equipment, $5.0 million for construction and repairs through the highway and bridge betterment program, $4.0 million for block grants to cities and towns for highway purposes, and $4.0 million for winter maintenance. The Senate voted to remove the latter two appropriations, leaving $11.0 million out of the $19.0 million appropriated by the House for these four purposes.

However, the Senate voted to appropriate an additional $5.0 million to the Department of Transportation to leverage federal grants that require a State cash match. The Senate also voted to appropriate $7.0 million to the Department to pay back funds drawn from the federal government to support the Conway Bypass right-of-way; the Conway Bypass project has been abandoned.

The Senate allocated $3.25 million to reconstruct and reclassify nearly two miles of Calef Hill Road in Tilton. The Senate also voted to permanently remove the toll booths from the northbound and southbound ramps of Exit 10 on the F.E. Everett Turnpike in Merrimack.

Finally, the Senate appropriated $50.0 million in General Fund SFY 2022 dollars to the Highway Fund. The Highway Fund would have balanced over the biennium, according to the Highway Fund Surplus Statement, but would have been diminished to a total of approximately $604,000. This appropriation boosts the estimated total at the end of the biennium to $50.6 million.[21]

Other Initiatives

The Senate proposed significant policy changes in other areas, including substantial modifications to the policies proposed by the House. As with most other sections of this Issue Brief, the focus of this section is on the changes to the House’s budget proposal made by the Senate.

Liquor Commission Law Enforcement Authority Restored

The New Hampshire Liquor Commission, which operates the State’s liquor stores, is required to enforce State laws and regulations governing the purchase, consumption, and proper control of alcoholic beverages, as well as overseeing access to tobacco products.[22] The House proposed removing this authority and 21 law enforcement positions at the Liquor Commission. Under the House’s proposal, enforcement would be conducted by county or city attorneys, sheriff’s departments, or town police, and the focus of the Liquor Commission would shift to education and licensing. The Senate voted to remove the House’s proposed changes, restoring the Liquor Commission’s law enforcement authority in the proposed budget and 20 law enforcement positions.

Family Medical Leave Insurance

In his budget, the Governor proposed establishing the Granite State Family Leave Plan, which would be a required plan for State employees and a voluntary plan for other entities, including businesses and individuals, seeking to join. Eligible employees would receive 60 percent of their average weekly wage for a maximum of six weeks per year, with a cap on the wage calculation for higher income earners. Employees would be eligible as the result of the birth of a child or placement of a foster or adopted child within the past year, a serious health condition of a family member, or for certain military-related care. The Governor’s proposal also included a tax incentive for businesses to join. The House voted to remove the Governor’s family medical leave insurance plan. The Senate added it back in, delaying the start date and making different procedures for participation in the plan for employers with fewer than 50 employees. Neither the Governor nor the Senate included an appropriation to support this insurance in their proposals.

Elimination of Unfilled State Employee Positions

The Senate’s budget would require that State agencies abolish all classified, full-time positions that were vacant prior to July 1, 2018 and remain vacant as of July 1, 2021. If someone is about to be hired into one of those positions and an offer for employment has been accepted, that position would not be eliminated. Executive branch agencies would have to supply the list of positions to be abolished to the Department of Administrative Services by September 1, 2021. The Department would then have to supply a written report of the positions abolished and the funds transferred, some of which would be required to support funds related to employee salaries and benefits, to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee. The Governor may grant individual exemptions to this policy.

Certain Restrictions on Teachings and Trainings

In its budget proposal, the House included a restriction on State officials, teachers in State-funded school districts, and contractors with the State government performing employee trainings related to certain aspects or concepts tied to race, sex, racism, sexism, oppression or stereotypes based in those concepts, and associating actions with someone based on their identity. The Senate modified this language.

The Senate narrowed the prohibitions on certain teachings or trainings related to aspects of systemic racism or sexism to remove the requirement for contracted entities. The Senate also substantially revised the language, and proposed inserting it into the state’s anti-discrimination statutes. The Senate’s proposal would forbid public employers, government programs, and school districts from teaching that an individual, by virtue of his or her age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, creed, color, or certain other characteristics, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Other Provisions

The Senate voted to make several other key changes to the House’s budget proposal, including:

- raising pay for certain State employees, including legislative and judicial staff and certain officials and employees in the Executive Branch, as well as a boost in longevity bonus pay for State officials, Troopers, and classified employees

- appropriating $10.0 million to help people who suffered financially due to Financial Resources Mortgage fraud

- adding $6.0 million to the Governor’s Scholarship Fund

- appropriating $3.0 million to the Department of Education for a State student data collection and reporting system

- allocating a total of $2.2 million additional funds to travel and tourism development and marketing efforts in two separate lines at the Department of Business and Economic Affairs

- removing the proposed limitations on the Governor’s emergency powers, which have been incorporated into a separate bill

- establishing two funds, likely to serve as frameworks for providing flexible federal aid from the American Rescue Plan Act, for businesses with 10 or fewer employees and for public venues

Revenue Projections and Tax Policy Changes

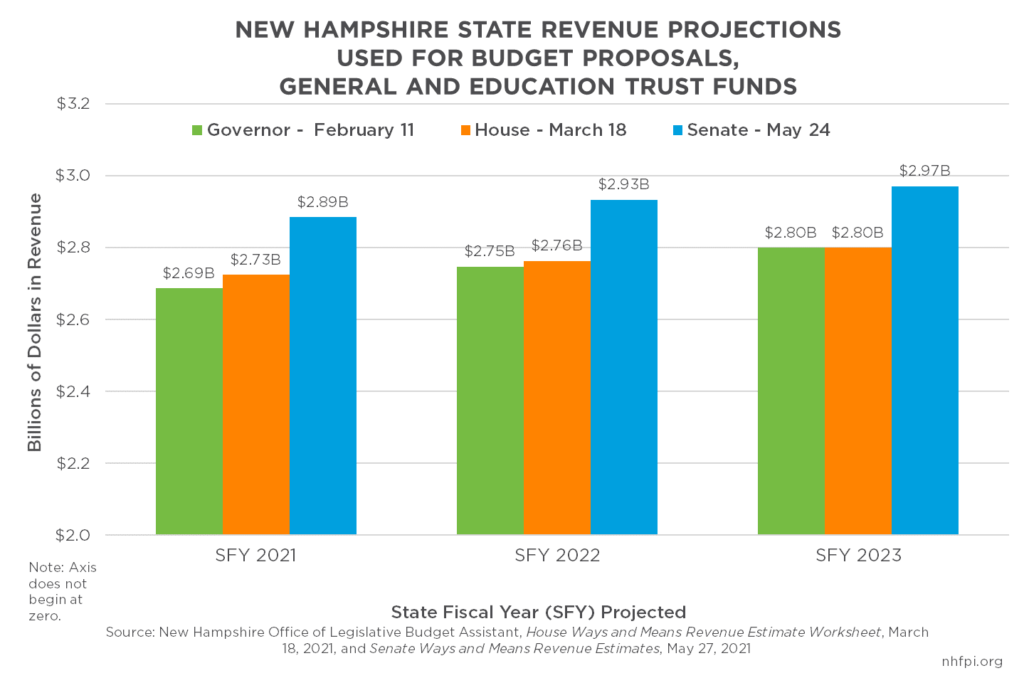

The Governor, House, and Senate all used separate sets of revenue projections for both existing policies and proposed revenue policy changes as a basis for funding decisions in their State Budget proposals. With a dynamic economic landscape and a fast-changing outlook, particularly following the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act, revenue projections have changed significantly since the COVID-19 crisis first struck New Hampshire. The Senate used substantially higher revenue estimates and proposed reducing revenue collections even further than the reductions proposed by the Governor and the House.

Revenue Projections

The Governor started the State Budget process with revenue projections provided in his February 11, 2021 State Budget proposal. The House adopted the estimates of the House Ways and Means Committee, which met to create an initial set of estimates and subsequently revised them upward following the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act. The March 18, 2021 projections for the General and Education Trust Funds used in the House’s version of the State Budget exceeded the Governor’s original revenue projections for the biennium. The Senate Ways and Means Committee met on May 24, 2021 to finalize their projections, which benefited from knowledge of the April 2021 State revenue receipts.

The Senate Ways and Means Committee’s revenue projections, which were adopted into the Senate’s version of the budget, were a total of $501.4 million higher than the House’s projections for the General and Education Trust Funds across three fiscal years. State Budget writers can deploy surplus SFY 2021 dollars to fund services during the SFYs 2022-2023 budget biennium, so higher revenue estimates for the remainder of SFY 2021 are a key consideration when estimating revenues.

None of the three sets of revenue projections, as presented in this section, include proposed revenue policy changes; the Governor’s revenue projections were adjusted to remove the impacts of his proposed tax policy changes, and the House and Senate Ways and Means Committees assume a baseline of current law in their revenue-projection processes.[23]

Revenue Policy Changes

The Senate retained the Governor’s and House’s proposed tax policy changes, and added two significant new tax policy changes into its proposal. The Senate left unchanged the Governor’s proposals to reduce the Business Enterprise Tax from 0.60 percent to 0.55 percent and to raise the two filing thresholds for the Business Enterprise Tax. The Senate also retained the Governor’s proposal to reduce the Meals and Rentals Tax from 9.0 percent to 8.5 percent, and to begin the phased elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax by the end of the State Budget biennium. The Senate also voted to retain the House-added proposal to reduce the Statewide Education Property Tax for one year, SFY 2023, by $100 million, and the House’s proposal to reduce the Business Profits Tax rate from 7.7 percent to 7.6 percent.

The Senate included two changes relative to the House version of the State Budget that substantially reduced projected revenues relative to the House. First, the House voted to delay the implementation of a change to the apportionment formula for business taxes. Apportionment is the process through which the State determines which portion of a multi-state business’s activities are attributable to New Hampshire, and thus become a part of the business tax base. The apportionment formula was set to move from a formula based on the proportions of a business’s property, personnel, and sales that were based in New Hampshire to a formula based only on sales. The House had voted to delay this transition, which is already prescribed in State statute, to 2026. The Senate’s version of the State Budget removed the delay, bringing the change to single sales factor earlier, and as a result reduced revenues in the official estimates by $20.0 million.

The Senate also voted to exempt federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) grants to businesses from the calculations of business income for purposes of the Business Profits Tax. Many businesses applied for PPP loans, most of which were turned into grants, during 2020. Many of those businesses also made a profit during 2020. Under current New Hampshire law, businesses must count PPP grants as income for the purposes of calculating profit. Businesses that made a profit, after other credits such as Business Enterprise Tax payments, would be taxed based in part on those PPP grant revenues. The Senate’s budget would exempt the PPP grants from the calculation of business income for the purposes of the Business Profits Tax. This provision is estimated to cost New Hampshire approximately $69.4 million during the biennium.

In total during the budget biennium, the Senate’s budget would reduce revenues to the General and Education Trust Funds by $247.1 million, according to the official estimates.

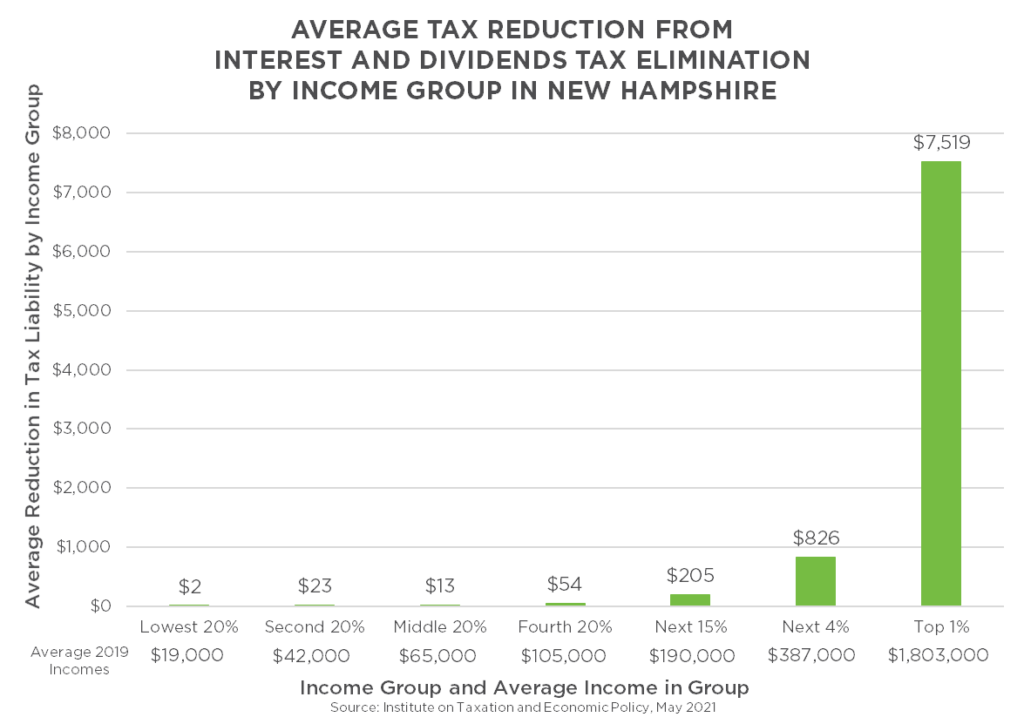

This projection, however, does not include significant future revenue reductions associated with the elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax, which would start in SFY 2023, near the end of the budget biennium. The Interest and Dividends Tax is a 5 percent tax on income earned by individuals and certain business entities from the ownership of certain assets. All three budget proposals would phase out the Interest and Dividends Tax by 2027, achieved by lowering the rates on an annual basis starting in 2023. The estimated total revenue lost due to this provision, using a static analysis conducted by the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, may be $368.9 million during the phaseout period through State Fiscal Year 2028, and then another $116.9 million annually thereafter.[24] The static analysis does not account for inflation or growth in the revenue base, such as positive performance in the stock market, which may make the actual revenue losses larger. The primary beneficiaries of this tax reduction would be high-income earners; an analysis from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy shows the change in 2019 tax liability for the bottom 20 percent of Granite State income earners was an average of $2 per person, while the highest-income one percent of New Hampshire residents would see a tax reduction of $7,519 per person on average. Nearly nine out of every ten dollars in the tax reduction would flow to the top 20 percent of income earners.[25]

The Senate also voted to remove two tax auditor positions at the Department of Revenue Administration that had been added by the House. This change results in an estimated $3.0 million less revenue collected, as a result of not employing these auditors who would have collected the revenue, to the General and Education Trust Funds during the State Budget biennium relative to the House’s revenue estimates.

Conclusion

The next State Budget will be supporting public services at a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, which may be a dynamic period for both public health conditions and the economy. New Hampshire residents will likely have higher needs for services early in the biennium, and many households continue to face difficulty covering usual expenses in New Hampshire.[26] Both federal assistance flowing to New Hampshire and State-based efforts will be needed to help ensure the recovery reaches the people, businesses, and communities who have been the most impacted by the pandemic.

The Senate proposed increasing overall levels of appropriations relative to the current State Budget, with significantly more resources deployed to the Department of Health and Human Services and non-education aid to local governments. The Senate would also boost aggregate funding for local public education relative to the budget proposals from the Governor and the House, but funding would remain lower in dollar terms than the current biennium due to both declines in enrollment and a decision to not repeat significant one-time aid in the current budget.

The Senate’s version of the State Budget provides more overall assistance, but less-targeted relief, to local governments in New Hampshire than either the current budget or the budgets proposed by the Governor and the House. The Senate’s revision of the Meals and Rentals Tax revenue-sharing statute would increase per capita assistance to New Hampshire municipalities substantially, even though it would lower the topline pledge from 40 percent of collected tax revenues to 30 percent. Meals and Rentals Tax revenues overall would be notably lower under the Senate’s proposal, however, because of the tax rate reduction. The per capita aid is less targeted to communities with lower incomes than the current State Budget’s $40.0 million in one-time aid, but is a larger amount overall.

Assistance for long-term care also avoids creating additional upward pressure on county property taxes while providing more funding for key services. The increases in nursing home funding and reimbursement rates for home and community-based care providers as an alternative to nursing home care will provide additional resources for those services that have been very critical during the pandemic and will continue to be both as variants of the virus circulate and New Hampshire’s population ages in the long-term. Certain key home and community-based services reimbursement rates have not kept pace with inflation in recent years, and bolstering these services represents an opportunity to both attract and retain the necessary workforce for their successful continuation and to save resources elsewhere by engaging in less expensive forms of care.

The Senate also made changes to property taxes relative to education funding with a one-time reduction to the Statewide Education Property Tax. This reduction would result in more resources flowing to communities from other State tax revenue sources, but would provide resources in a less targeted manner than the fiscal capacity disparity aid in the current State Budget. The proposed budget would also send additional aid to communities with relatively high property wealth and low numbers of students, associated with and in addition to the tax reduction itself.

The Senate added a separate provision that would target more aid to communities with more students from families with low incomes, helping those who may have the least income to support services in their local communities. The Senate’s changes to provide a funding buffer for those school districts that saw steep declines in enrolled students will also assist communities that may face more difficulty recovering from the COVID-19 crisis. However, the Senate proposed adding a key variable that makes future education funding for school districts and the expected expenses for the State’s Education Trust Fund considerably less certain; the addition of Education Freedom Accounts will require more resources from the Education Trust Fund for each student who would be newly funded through one of these Accounts.

The Senate’s budget also makes key appropriations to support housing for residents in need of mental health care and for housing infrastructure more generally. Investments in mental health services and enhanced reimbursement rates for transitional housing beds are made in addition to funding for a psychiatric hospital. The Senate also supported a significant one-time appropriation to the Affordable Housing Fund.

Tax reductions proposed by the Senate may hinder the State’s ability to fund public services in both this biennium and the long-term. The Senate’s budget includes permanent rate reductions for the State’s largest, third-largest, and fifth-largest tax revenue sources, and a significant temporary reduction for the second-largest tax revenue source. In addition, the Senate’s proposal would completely phase out the tenth largest tax revenue source, the Interest and Dividends Tax, which provided about one out of every twenty dollars in all revenue collected by the General and Education Trust Funds last year.[27] The elimination of this tax would disproportionately benefit individuals with high wealth and high incomes, who have been among the least impacted by the economic disruptions of the pandemic.

The budget proposed by the Senate includes some significant, non-financial policy changes. Limitations on certain reproductive health care do not have a direct budgetary impact, and restrictions on certain speech related to systemic racism and sexism in schools and public employment does not alter any funding lines while risking diminishing the value of public programs and training.

Public policy can help build an inclusive, equitable, and sustainable economic recovery. Assistance to individuals and families with low incomes can both help enable those households to make ends meet and effectively boost economic growth. Significant federal assistance supplemented by investments, coordination, and intentional public policy choices by State policymakers can help bolster the recovery. Maximizing federal assistance to Granite Staters, through both State policy choices and connecting eligible individuals to services, can enhance New Hampshire’s recovery and help ensure Granite Staters have the resources to support their families, engage in the economy, and help New Hampshire’s businesses and communities emerge stronger from the pandemic. The next State Budget can deploy resources thoughtfully and effectively to foster a healthy economy and support Granite Staters in the pivotal years following the COVID-19 crisis.

Endnotes

[1] The analysis in this Issue Brief is based primarily on House Bill 1, as Amended by the Senate, and House Bill 2, as Amended by the Senate, both of which were passed by the New Hampshire Senate on June 3, 2021. This Issue Brief also draws on analysis provided by the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s June 3, 2021 Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus for the Combined General and Education Trust Funds, June 7, 2021 Compare Senate to House Report, and June 4, 2021 Detail Change Senate Vs. House Report. To understand key differences between the Governor’s budget proposal and the current State Budget, see NHFPI’s March 11, 2021 Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023. To understand key differences between the Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s version of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s April 26 Issue Brief The House of Representatives Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023. For relevant background on the economy and likely needs during the upcoming budget biennium, see NHFPI’s February 8, 2021 Issue Brief Designing a State Budget to Meet New Hampshire’s Needs During and After the COVID-19 Crisis.

[2] These totals are net of interagency transfers, which are removed from the State Budget line items because they are double-budgeted appropriations associated with payments to the Department of Information Technology by other agencies.

[3] To learn more about the changes proposed by the Governor relative to the current State Budget, see NHFPI’s March 11 Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023. To understand key differences between the Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s version of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s April 26, 2021 Issue Brief The House of Representatives Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023.

[4] Medicaid enrollment data from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography, May 2021. For the cost of Medicaid, see NHFPI’s December 7, 2020 presentation The COVID-19 Crisis and State Budget Implications for New Hampshire.

[5] The Authorized Adjusted amount referenced is the figure reported by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant in the Senate Finance Committee Budget Briefing, June 1, 2021.

[6] For more information on county roles in Medicaid under current State law, see NHFPI’s August 1, 2019 Fact Sheet County Medicaid Funding Obligations for Long-Term Care.

[7] To learn more about the Choices for Independence Medicaid Waiver program, see NHFPI’s March 15, 2019 Issue Brief Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Care Service Delivery Limited by Workforce Challenges.

[8] For more information, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Sununu Youth Services Center.

[9] For an example of declining average census counts, see Table 6 of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Operating Statistics Dashboard, November 2019.

[10] For information and research related to the importance of child care in the economy and the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, see the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Community Development Research Brief, Child Care, COVID-19, and Our Economic Future, September 2020.

[11] To understand the changes in enrollment between the 2019-2020 school year and the 2020-2021 school year by the municipality of the student’s home, see the New Hampshire Department of Education’s State Adequacy Aid Documents packet presented to the House Finance Committee on March 3, 2021.

[12] For more details on the State’s Adequate Education Aid formula, see NHFPI’s May 6, 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget. See also the New Hampshire Department of Education’s November 15, 2020 publication FY2022 Adequate Education Aid.

[13] For this cost estimate, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant-drafted amendment to House Bill 1 corresponding to House Bill 2 amendment 2021-1752s.

[14] For the 2021 federal poverty guidelines figures, see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2021 Poverty Guidelines Computations. For more on free and reduced-price school lunch eligibility, see NHFPI’s May 6, 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[15] See the New Hampshire Department of Education’s State Adequacy Aid Documents packet presented to the House Finance Committee on March 3, 2021. For more information on the policy’s structure, see NHFPI’s December 20, 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[16] For more information, see the New Hampshire Department of Education’s School Building Aid Summary, March 3, 2021, provided to the House Finance Committee’s Division II.

[17] To learn more about the American Rescue Plan Act, see NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services.

[18] Read more about the House’s proposed SWEPT reduction in NHFPI’s April 26, 2021 Issue Brief The House of Representatives Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023 and NHFPI’s May 11, 2021 blog Statewide Education Property Tax Change Provides Less Targeted Relief.

[19] A town-by-town estimated breakdown was produced by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant on June 2, 2021.

[20] To learn more about these funds, see NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[21] To see the expected Highway Fund balance at the end of the biennium, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s June 3, 2021 Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus for the Highway Fund.

[22] For more information, see the 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the New Hampshire Liquor Commission.

[23] To see more information regarding the House Ways and Means Committee revenue estimates and process, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, House Ways & Means Revenue Estimate Documents – February 2021. For Senate Ways and Means Committee revenue estimates, see the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Senate Ways & Means Revenue Estimates – May 27, 2021.

[24] See the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s February 22, 2021 document titled I&D Tax Rate Phase Out.

[25] Read more about the potential revenue and distributional impacts of eliminating the Interest and Dividends Tax in NHFPI’s May 21, 2021 blog Elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax Would Disproportionately Benefit High-Income Individuals.

[26] For more information on the ongoing economic impacts of the pandemic, see the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey and NHFPI’s April 9, 2021 blog The COVID-19 Crisis After One Year: Economic Impacts and Challenges Facing Granite Staters.

[27] For more information on State tax revenue sources, see NHFPI’s May 13, 2021 presentation How Public Services are Funded in New Hampshire at the State and Local Levels.