The Governor’s February 2023 proposal for the next two-year State Budget arrived in an environment of potentially increased overall need for services, particularly with looming economic uncertainty and the end of key federal COVID-19-related fiscal supports for programs and the economy. The next State Budget will fund State-supported services during the upcoming two fiscal years. With State finances buoyed following a period of substantial increases in State revenue, State policymakers enter this new period of uncertainty with considerable financial capacity. These recent revenue increases, primarily driven by a significant upswing in national corporate profits that has accelerated since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, have provided the State with substantial opportunities to address immediate needs and longstanding challenges. However, the corporate profits fueling business tax revenues may decline if an economic slowdown or recession occurs during the next State Budget biennium. Concurrently, a slowing economy may increase public service needs as more people lose employment or income. If the economy weakens substantially, continuing to provide key public services during the next State Budget biennium will be essential for directly supporting individuals and families as well as for providing economic stimulus. Reducing State revenue could put these key services at risk.[1]

The House voted to substantially change the Governor’s State Budget proposal. Both proposals would allocate significantly more funds to State services than were approved for the current State Budget biennium in 2021. The increases in this proposal reflect an acceleration in inflation that has raised the costs of providing services, the reduced availability of federal COVID-19 funds, and several new initiatives to support Medicaid services, access to child care and food, and significant revisions within the State’s education funding formula.

Relative to the Governor’s State Budget proposal, the House proposed adding significantly more funding for Medicaid reimbursement rates. With lower revenue estimates, the House would also add less revenue to the State’s Rainy Day Fund than the Governor, although it would devote surplus funding to marginally helping pay down the State’s unfunded pension liability. The House also would retarget school funding increases relative to the Governor, adding provisions to the funding formula for local public education that would focus more resources on municipalities with less fiscal capacity. The House removed most of the Governor’s proposed reforms to professional licenses in the State. The House Budget would retain the Communications Services Tax, which the Governor would have repealed, and the House voted to accelerate the planned elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax.

This Issue Brief examines key components of the New Hampshire House of Representatives’ State Budget proposal for the next two fiscal years and focuses on changes made relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, incorporating comparisons to the current State Budget for context for certain changes. The Issue Brief also reviews revenue projections and proposed changes to State tax policy in the House’s State Budget proposal. For comparisons between the Governor’s proposal and the current State Budget, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief on the Governor’s State Budget proposal.[2]

The Topline Changes

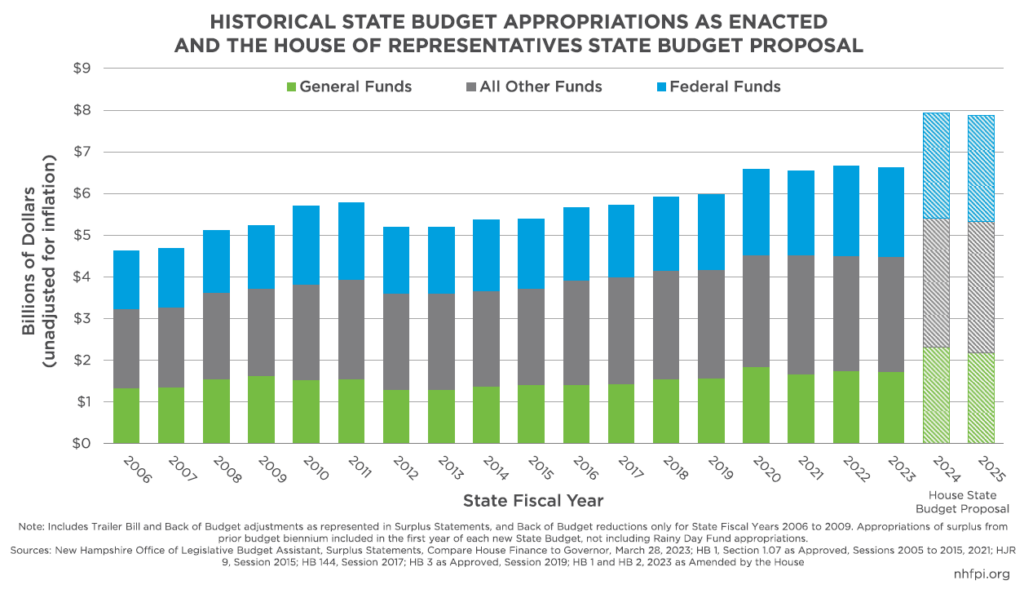

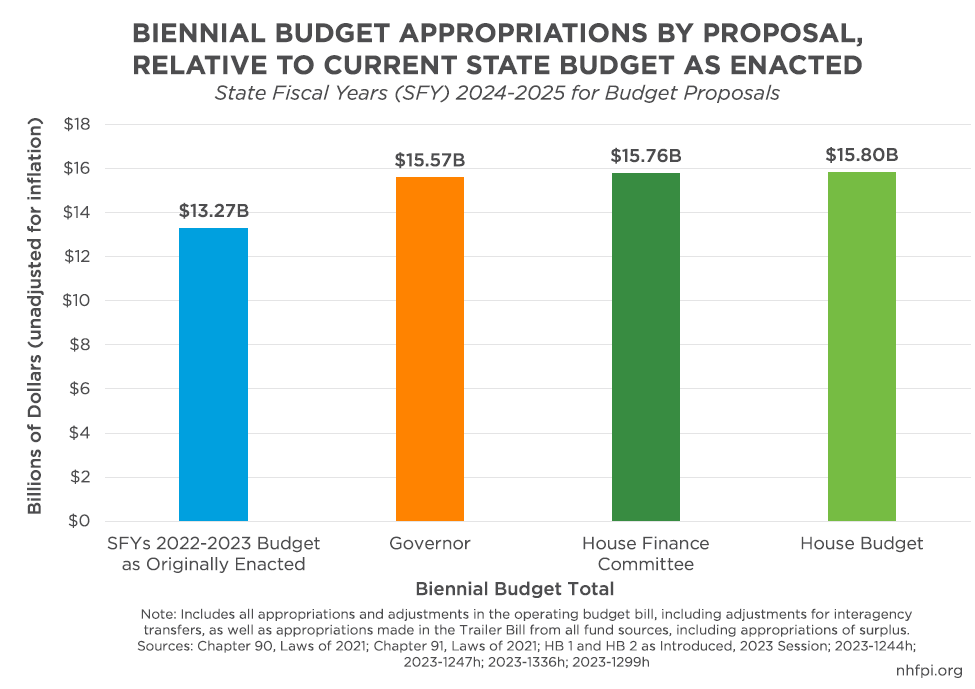

The House’s proposed budget for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024 and SFY 2025 would spend substantially more, unadjusted for inflation, than prior State Budgets and continue the trend of increasing aggregate appropriations from budget cycles since the SFYs 2012-2013 State Budget. The House’s proposal, net of interagency transfers related to information technology services, would appropriate $15.8 billion during SFYs 2024 and 2025, a 19.1 percent increase from the comparable SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget total as enacted in June 2021, and a 1.5 percent increase from the Governor’s proposal.[3] Some of this increase likely reflects faster growth in the cost of providing the same services due to inflation.[4]

The proposed increase passed by the House was enabled by changes made to the House Finance Committee’s proposal. The House Finance Committee appropriated $15.76 billion relative to the Governor’s $15.57 billion and the final State Budget proposal from the House of Representatives was $15.80 billion.

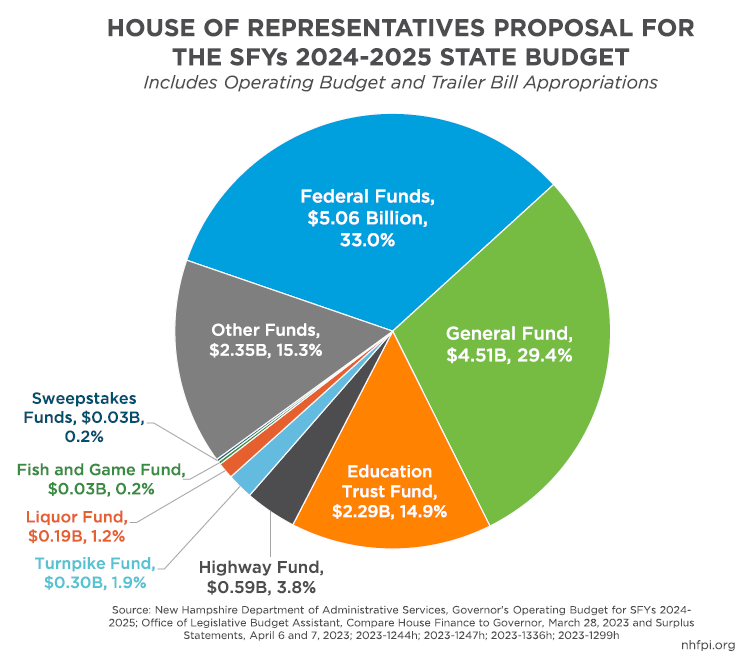

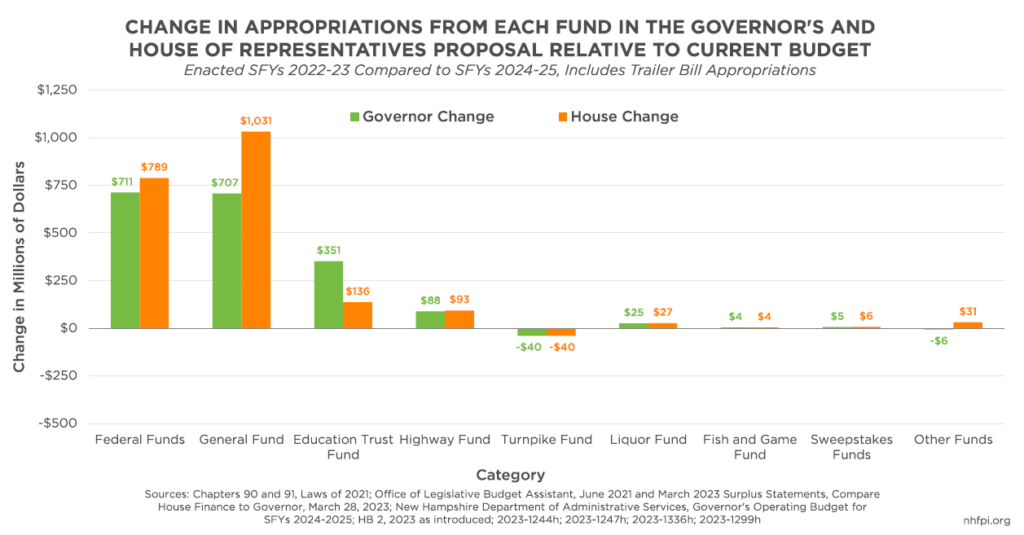

Not all funding areas would expand evenly under the House’s State Budget proposal relative to the Governor’s appropriations. Of the State Budget’s major funds, which are the legal structures organizing State Budget appropriations, the House proposal budgets larger increases than the Governor’s in both Federal Funds and General Funds, with General Funds leading the increase. While the Governor anticipates that transfers from the federal government to fund State Budget expenditures would increase by $711.4 million (16.7 percent) in the upcoming biennium relative to the amounts anticipated by the current State Budget as passed in 2021, the House anticipates $788.5 million (18.5 percent). Neither State Budget proposal appears to explicitly budget the flexible aid to the State provided by the federal American Rescue Plan Act, which has been allocated outside of the lawmaking process and through the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Executive Council, although the House Budget has a provision that would draw upon those funds for an expense accounted for outside of the State Budget.[5]

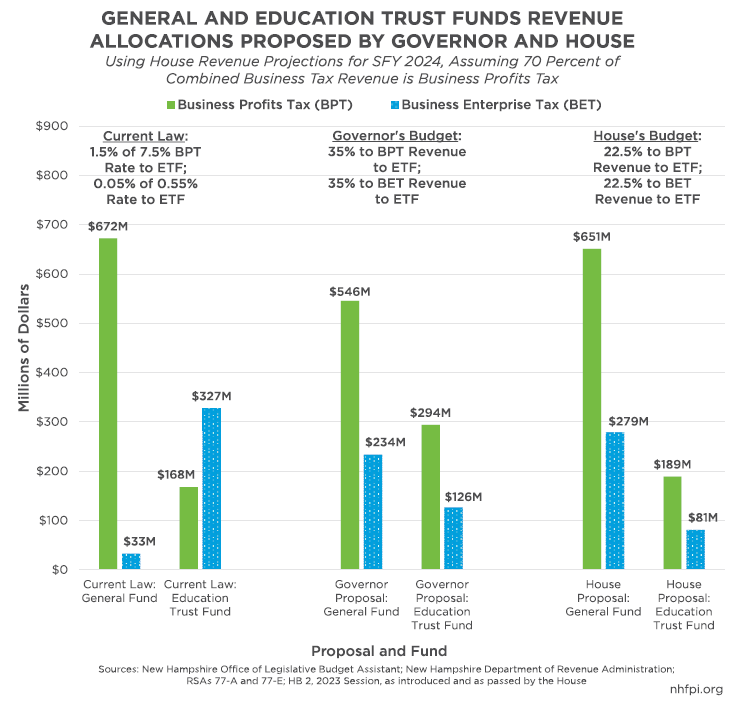

The House budget would expand General Fund expenditures by $1.031 billion (29.6 percent) relative to the prior biennium, constituting the largest increase in dollars among the major funds. The Governor’s proposed increase was $707.1 million (20.3 percent) from the prior biennium. The percentage increase in General Funds proposed by the House budget is larger in part because of the House’s decision to divert a substantial amount of revenue from the Education Trust Fund to the General Fund relative to both the current State Budget and the Governor’s proposal. Despite substantial new investments in local public education through the education funding formula in both the Governor’s and the House’s proposals, Education Trust Fund appropriations in the House’s State Budget proposal would increase by $136.0 million (6.3 percent) over the biennium relative to appropriations under the current State Budget, compared to the Governor’s $351.4 million (16.3 percent) increase in Education Trust Fund appropriations.

These appropriations include allocations of General and Education Trust Funds surplus revenue over expenditures in the current State Budget. These surpluses and revenue projections for the next budget biennium reflect the substantial increase in revenues since SFY 2020, supported by the rebounding economy following the worst periods of the COVID-19 pandemic and soaring national corporate profits that have boosted Business Profits Tax receipts.[6]

The House would increase expenditures from the Highway Fund by slightly more than the Governor’s proposed $88.0 million (17.8 percent) increase. The House’s $93.4 million (18.9 percent) boost is enabled in part by a proposed transfer of $10.0 million from the General Fund to the Highway Fund. The House retained the Governor’s suggested appropriations from the Turnpike Fund, which would decline by $39.7 million (11.8 percent) relative to the current State Budget as enacted.

Expenditure by Category of Government Services

All State Budget expenditures are allocated to one of six categories based on the service area of each department. These six categories are designed to cover all areas of State government operations, and include General Government, Justice and Public Protection, Resource Protection and Development, Transportation, Health and Social Services, and Education.

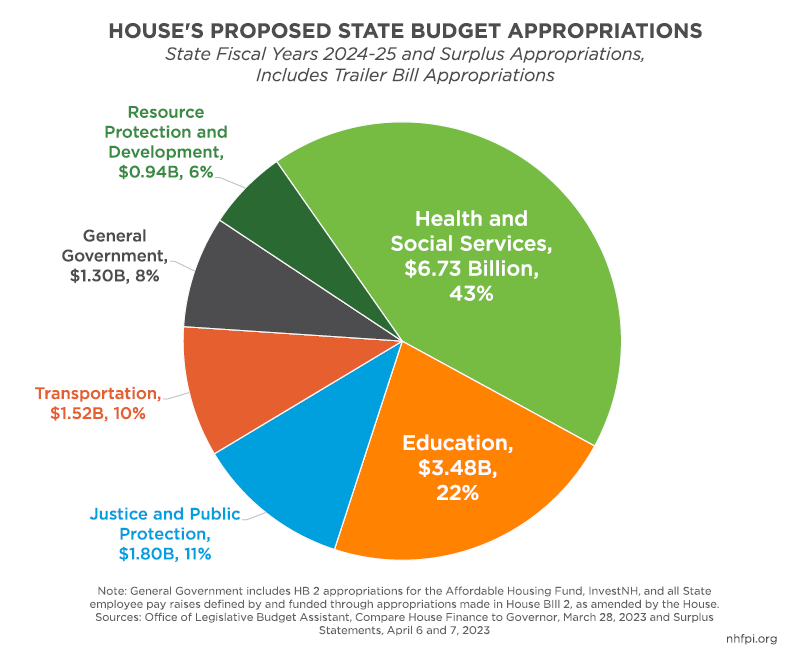

Similarly to the current State Budget, the House’s budget proposal would allocate the plurality of funds, totaling $6.73 billion (42.7 percent), to Health and Social Services, including General Fund and Federal Fund appropriations as well as appropriations from all other funds. Education would receive just over a fifth of appropriations, totaling $3.48 billion (22.1 percent). Justice and Public Protection would receive the next largest appropriation, with $1.80 billion (11.4 percent) appropriated during the biennium. Transportation would follow with $1.52 billion (9.6 percent), General Government with $1.30 billion (8.3 percent), and Resource Protection and Development with $941.5 million (6.0 percent).

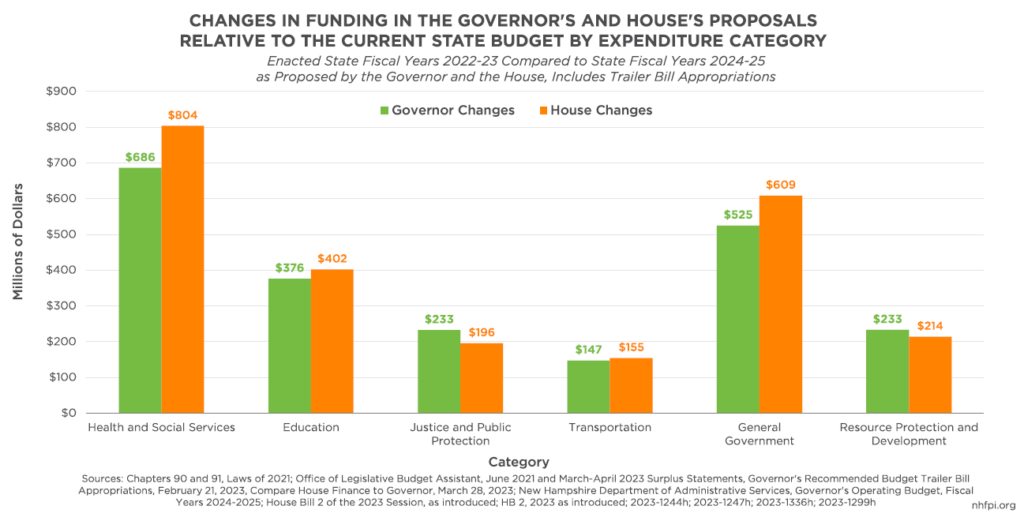

The largest dollar increases, relative to the current State Budget as passed, would go to Health and Social Services, although the category would decline as a percentage of the entire State Budget. Health and Social Services, which is almost entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) budget, would rise by $803.7 million (13.7 percent), a larger increase than the Governor’s proposal. Among other factors, the House’s proposed increase relative to the Governor’s budget is due to the House adding funding for targeted Medicaid reimbursement rate increases and recognizing federal funds that would be drawn down associated with Medicaid information technology infrastructure investments.

Education, the next-largest category in the State Budget, would see a higher amount relative to funding from the current biennium’s appropriations under the House’s proposal as well. The majority of expenditures in this category are driven by the Adequate Education Aid paid primarily based on per pupil grants to local governments to help fund public education. This category also includes funding for the University and Community College Systems and operations at the New Hampshire Department of Education, the Police Standards and Training Council, and the Lottery Commission, which generates revenue to support the Education Trust Fund. Relative to the Governor, the House added targeted funding for initiatives at the Community College System, funding for expanded enrollment of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals associated with policy changes, and for other education initiatives while reducing funding for Education Freedom Accounts and funding for an incentive and professional development program for educators in computer science. The House’s changes to the Adequate Education Aid formula proposed by the Governor resulted in a change of only approximately $800,000 in expenditures during the biennium, although the funds would be directed differently among communities. In total, funding for Education would rise $402.4 million (13.0 percent) relative to the current State Budget as enacted under the House’s proposal, $26.5 million more than the Governor’s proposed increase.

General Government would see the largest percentage increase and the second-largest dollar increase, rising $608.6 million (89.7 percent) over the prior State Budget biennium as enacted in the House’s proposal. This increase is $84.0 million more than the boost proposed by the Governor, due primarily to a $100 million increase in investments in the New Hampshire Retirement System and declines in funding related to the construction of a new legislative parking garage, which was shifted to a separate piece of legislation outside of the State Budget.

Other shifts made by the House relative to the Governor’s proposal are smaller in magnitude. All categories would see appropriations grow relative to the current State Budget, but the House reduced funding for Resource Protection and Development and for Justice and Public Protection relative to the Governor’s proposal. The reductions in Resource Protection and Development funding were due in part to the House reducing the Governor’s proposed allocations for the InvestNH housing development fund, for New Hampshire Public Television, and for the proposed Office of Regulatory Review, Reduction, and Government Efficiency. Justice and Public Protection received smaller allocations relative to the Governor due in part to reductions in funding for a new State prison for men, in the judicial branch, and the Governor’s proposed northern border enforcement program.

Proposed Changes by State Agency

State agency-level analysis provides additional insight into the changes proposed by the House relative to the Governor’s budget. The previous analyses in this Issue Brief comparing budget categories and funds provide comparisons between the two-year budgets proposed by the Governor and the House as well as the two-year State Budget approved by policymakers in 2021. The analysis of State agency budgets in this section compares the appropriations in the Governor’s budget proposal by State agency, including appropriations for the entire biennium, with the changes made and proposed by the House of Representatives in its State Budget proposal. These comparisons do not include the application of the proposed 10 percent pay increase in SFY 2024 and subsequent 2 percent increase in SFY 2025 for all State employees; this policy change will translate into higher budgets for departments once the pay increase is incorporated into individual agency budgets, but these changes are not currently parsed out between agencies in the published agency-level appropriations.[7]

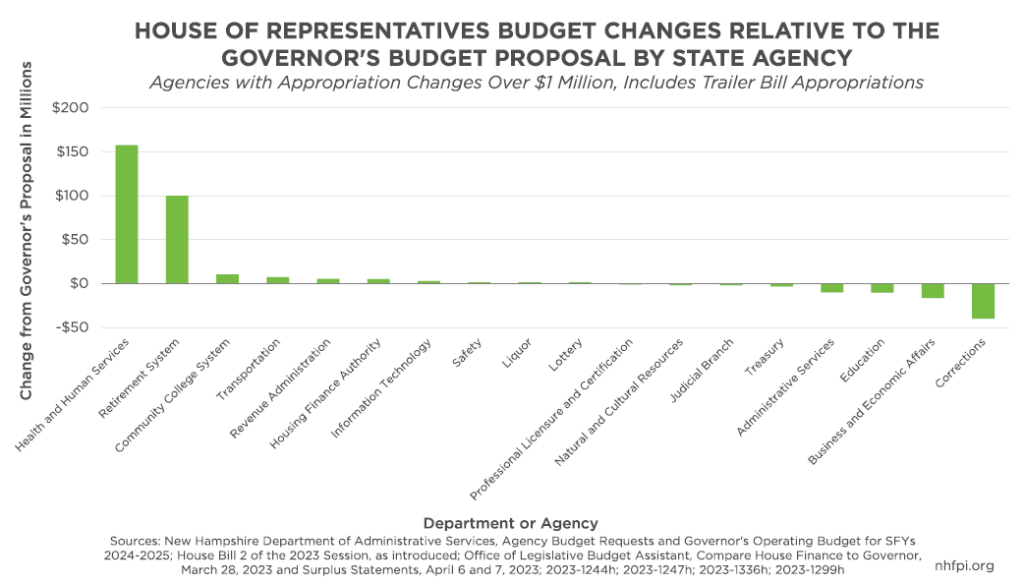

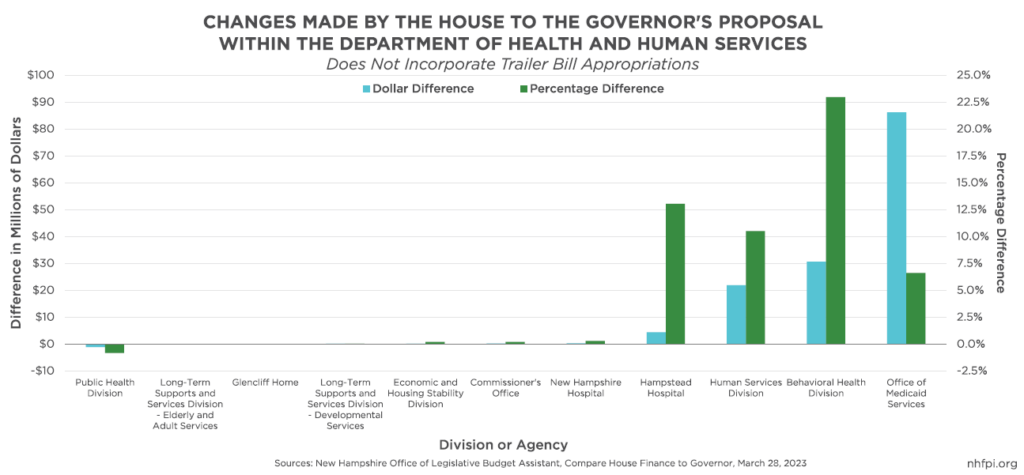

Relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, the House voted to change funding levels at 25 of 40 State agencies as categorized in the State Budget. The largest increase was a $157.7 million boost at the Department of Health and Human Services, followed by a $100 million increase at the New Hampshire Retirement System, and a $10.5 million boost for targeted projects at the Community College System. Seven State agencies had proposed funding changes of less than $1 million relative to the Governor’s budget proposal.[8]

Health and Human Services

The House included substantial increases to funding for health services relative to the Governor’s State Budget proposal. The House’s budget would add significant targeted rate increases to the smaller, general rate increase included in the Governor’s proposal, while also expanding Medicaid coverage for key populations, including with a two-year extension of the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program.

Medicaid Reimbursement Rate Increases

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership that helps ensure people with low incomes, limited resources, or in need of long-term care have better access to health services. Medicaid typically behaves like private insurance, reimbursing health care providers for services to enrollees who would likely not be able to afford them otherwise. However, Medicaid reimbursement rates are commonly lower than those funded by private insurance or the federal Medicare program for older adults. NHFPI research published in July 2022 determined that key New Hampshire reimbursement rates for home and community-based long-term care, as well as overall funding for these services, fell behind inflation in costs between SFYs 2011 and 2021; lower funding levels may have contributed to lower wages, reducing the capacity of providers to deliver needed Medicaid services.[9]

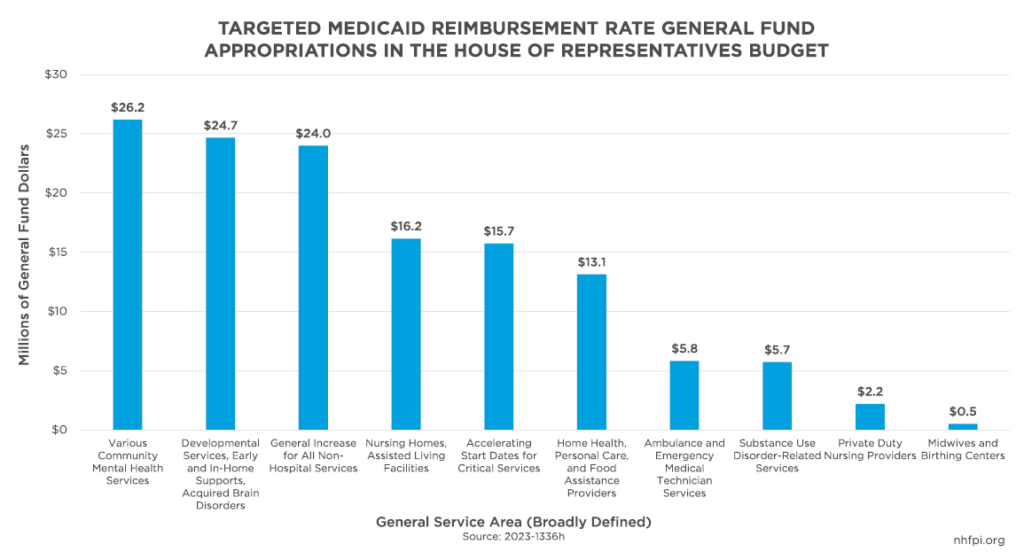

The House’s budget includes $24 million in State funds for rate increases generally, appropriated through a $12 million allocation in each year, to support Medicaid provider rates excluding hospital inpatient and outpatient services. This amount is a reduction from the Governor’s budget, which did not carve out hospital services from the reimbursement boosts. However, this general rate increase is complemented by an additional targeting of $110.2 million in State funds specifically for reimbursement rate increases in identified service areas. State fund totals allocated toward this purpose will be at least doubled by federal matching dollars, with a higher matching rate in certain programs.

The $110.2 million in State funds dedicated to Medicaid reimbursement rates proposed by the House would vary across service area, and would take effect in January 2024. The largest aggregate increases would be in various forms of community mental health services, including providers, mental health centers, housing services, and increasing rates to be on par with similar Medicare reimbursement rates. The next-largest amount of funding would be allocated collectively for developmental services, early supports and services, in-home supports, and acquired brain disorders. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities would also receive funding boosts, as would home health and personal care assistance through the Choices for Independence Medicaid waiver program and Meals on Wheels programming. Medicaid rates would also be increased, funded by smaller dollar amounts, for ambulance and emergency medical technician reimbursement, substance use disorder related services, private duty nursing providers, birthing centers, and midwives.

The House budget also sets aside $15.7 million for the DHHS to target certain services for accelerated start dates. Recognizing these enhanced reimbursement rates would not begin until January 2024, the House budget provides flexibility in this funding for the DHHS to fund earlier start dates from among the services identified for targeted rate increases by legislators.

Expansions of Medicaid Eligibility

The House included three expansions of Medicaid eligibility in its budget proposal.

First, the House would extend the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, typically referred to as Medicaid Expansion, for adults with low incomes as enabled by the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The House would reauthorize this program, which served 81,052 Granite State enrollees with low incomes at the end of April 2023, for a two-year period.[10] The current reauthorization, which is a five-year reauthorization, expires at the end of calendar year 2023. The House would also alter the funding structure for the non-federal share of the Granite Advantage program, which accounts for ten percent of program costs to match the ninety percent of funding received from the federal government. The House would cap the amount of State-raised funding coming from insurance companies through an assessment while removing the required contributions from the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund and increasing reliance on revenues collected and directly transferred from the Liquor Commission, which are generated largely by State liquor store sales.[11] The State Senate has passed a separate bill that would permanently reauthorize the program.[12]

Second, the House’s budget would expand Medicaid to make 12 months of postpartum coverage available to anyone who received Medicaid-funded services for all pregnancy-related care. Current policy provides this coverage for 60 days, but the federal government recently enabled federal matching dollars for the year following childbirth.[13]

Third, the House expanded coverage to include certain immigrant children and pregnant women who are lawfully in the United States and are otherwise eligible for Medicaid. This expansion would include children up to age 19 years and pregnant women for the postpartum period.[14]

Sununu Youth Services Center

The House removed the appropriation in the Governor’s State Budget proposal that would have allocated $10 million to the Department of Administrative Services to help fund the successor facility to the Sununu Youth Services Center. Instead, the House would require that any funds used in the construction of such a facility would be drawn from flexible federal funds allocated to the State through the American Rescue Plan Act. The House also shifted funding for the Sununu Youth Services Center during the budget biennium to be reflected in a different manner in the State Budget, including the appropriations in the regular budget lines rather than in a separate appropriation.[15]

Other Health and Human Services Funding and Policy Changes

The House voted to make several other key changes to the Governor’s budget proposal relative to the DHHS, including:

- increasing funding for behavioral health services by $28.1 million during the biennium to support children’s residential rates and bolster provider capacity within the system of care

- appropriating $5 million to support residential treatment provider rates as part of the system of care

- rolling $28.6 million from the current State Budget forward to the next biennium to fund developmental services from the expected lapse generated by underutilization of these services during this biennium, likely due to workforce constraints

- halting increases in expected county payments for the non-federal share of Medicaid long-term services and supports, which typically increase every year, and adding $18.5 million in State funds to offset county costs

- providing an additional $4.4 million to support operations at Hampstead Hospital during the biennium

- adding $2.1 million in funding to the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention, Treatment, and Recovery

- shifting Medicaid information technology upgrades in State Budget accounting to account for an expected $65.7 million in federal revenue

- funding of $500,000 for a kidney cancer study for the Town of Merrimack

- adding $400,000 in appropriations for five specific youth substance use prevention programs

- supporting the Office of Child Advocate with $200,700 in funding for a case management system upgrade

- eliminating the Governor’s proposed requirement that hospitals have Designated Receiving Facility beds as a condition of licensure

- removing funding for juvenile peer grief support, as well as for recovery-friendly workplaces

- reducing funding for the Division of Public Health due to adjustments associated with family planning services to match an expected federal grant amount

- establishing a new Data Privacy and Information Technology Security Governance Board within the DHHS

- suspending aspects of State Health Care Facility Workplace Violence Prevention Program for the biennium, and changing requirements regarding rules for the program

- adding new reporting and competitive bid requirements to the Prescription Drug Affordability Board, and establishing a new dedicated fund for the Board

- removing a proposed audit of the integrated eligibility system

Back of the Budget Funding Reduction

Funding for the DHHS in the House’s budget proposal would be reduced by $23.4 million in General Fund appropriations during the biennium. The DHHS is directed to find these savings within appropriations made in the agencies operating budget lines, but does not specify where these reductions should occur. The DHHS would be required to report on these reductions annually. Associated with this provision, the DHHS would be limited to 3,000 filled, full-time, authorized positions at all times during the biennium.

Child Care

The House proposed three significant changes to child care funding relative to the Governor’s budget. All three would help support enhanced access to child care.

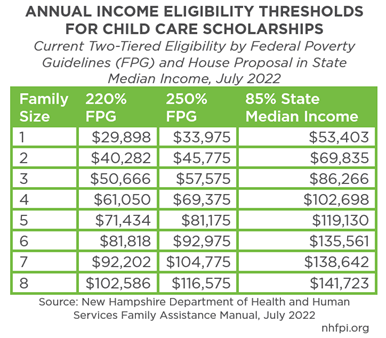

First, the House’s State Budget proposal would increase the income eligibility threshold for Child Care Scholarships for the biennium. These Scholarships are subsidies for families to help them afford child care. Families receive assistance to pay child care costs, and have a required family contribution that increases with family income; parents or cohabitating adults must be working, seeking work, receiving certain mental health or substance misuse-related services and participating in certain other services funded by federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) resources managed by the State, or participating in eligible training or educational programs to qualify for assistance.[16] Under current law, families must have incomes below 220 percent of the federal poverty guidelines when they apply, or about $50,666 for a family of three, to be eligible to receive any subsidy through the Child Care Scholarship program. Families already on the program whose incomes rise may temporarily remain eligible up to 250 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $57,575 for a family of three. The House budget would, during the next budget biennium, raise the income threshold for eligibility to 85 percent of State Median Income, which the DHHS identified as $86,266 for a family of three in July 2022.[17] This increase would likely make many more families eligible for some form of subsidy. In 2021, approximately 51,700 New Hampshire families, or about 14 percent of all families in the state, had an annual income between $50,000 and $74,999, and another 46,600 (13 percent) had incomes between $75,000 and $99,999.[18]

Second, the House budget would increase the reimbursement for child care providers who are serving children with Child Care Scholarships. Currently, the reimbursement provided by the State is determined by a market rate survey. Reimbursements to providers are set at the 60th percentile of the market rate for children up to age three years, and the 55th percentile for children ages three and over.[19] The House budget would increase this reimbursement to the 75th percentile of the market rate survey for the biennium, or would set reimbursements based on a “true cost of care” mechanisms that has not yet been established, but would be defined by the DHHS. Increases in payments to providers have the potential to help ease workforce shortages and enhance the availability of child care.

Third, both of these expansions in eligibility and in payment would be funded through the State Budget, but would also have a backstop. To avoid or mitigate child care waitlists associated with State funding limitations, both these new initiatives and certain other employment-related child care services in the State Budget would be backstopped by TANF dollars.

Education

The Governor‘s budget included substantial changes to education funding, including both significant changes to the funding formula for local public education and the expansion of eligibility for Education Freedom Accounts, which are accessible for private use by families on education-related expenses such as private school tuition and homeschooling expenses. The House significantly altered the Governor’s proposed changes to the education funding formula in its State Budget proposal, while still substantially changing the existing formula, and removed the expansion of Education Freedom Account eligibility from the budget proposal. The House also added targeted funding for projects at the Community College System while shifting certain funds for the University System.

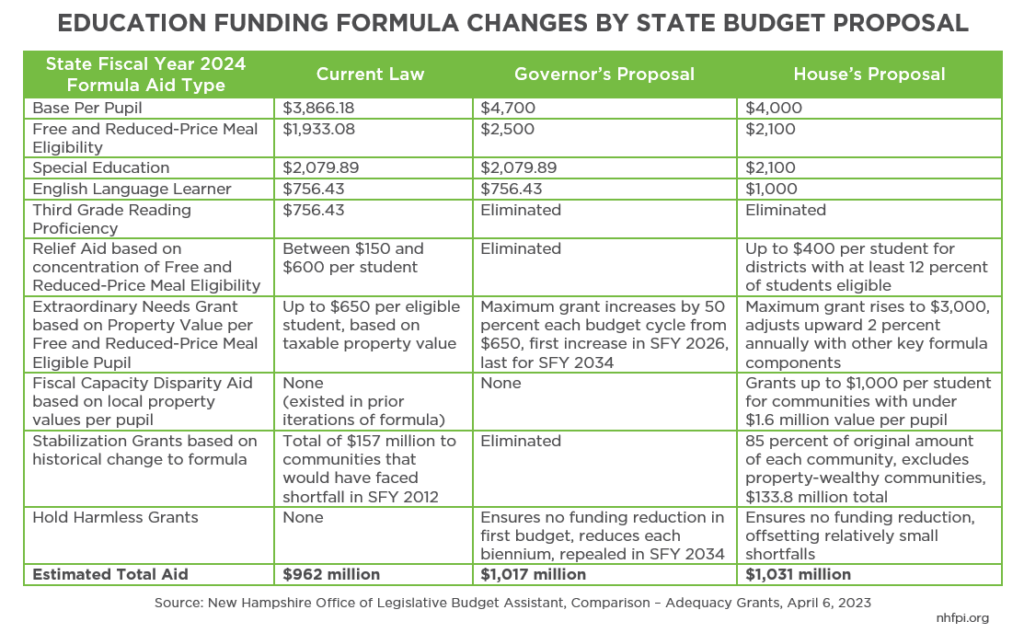

Adequate Education Aid for Local Public Schools

The primary mechanism through which State funding is supplied to local public schools for supporting education is Adequate Education Aid. The majority of this assistance comes in the form of per pupil Adequate Education Grants, which include base grants of $3,866.18 per full time student in SFY 2024, under current law, with additional per pupil funding for students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, students receiving special education assistance, and English language learners. School districts also receive additional funds based on community characteristics, including based on the concentration of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, typically due to low household incomes at home, and taxable property value within a community for each economically disadvantaged student.[20]

The House proposed substantially reducing the amount of funding the Governor recommended as the baseline amount per student, while also providing an increase from current law. In SFY 2024, per pupil funding would be $3,866.18 under current law; the Governor had proposed a boost to $4,700, with an inflation adjustment every year. The House budget proposal would bring base per pupil funding up to $4,000 and establishes a planned 2 percent annual increase in the base amount and in other key parts of the formula. The savings associated with lower base per pupil funding relative to the Governor was used by the House to target more aid to communities with lower property values and more free or reduced-price school meal eligible students.

While both the Governor and the House would eliminate additional funding in the current formula for students who scored below proficient on their third-grade reading tests, the House would boost all other types of aid targeted based on the characteristics of individual students. Free and reduced-price school meal eligible students would receive $2,100 from the State for their districts, a drop from $2,500 in the Governor’s proposal but a boost relative to the current $1,933.08 for SFY 2024. The House would also slightly increase aid for Special Education students, and substantially boost aid for students who are English language learners, relative to both current policy and the Governor’s proposal.

The House’s more targeted aid, however, comes in the form of assistance based on community characteristics. The Governor’s proposal would have simplified the school funding formula, eliminating aid based solely on community-level free and reduced-price school meal eligibility, as well as eliminating Stabilization Grants, which offset funding losses for communities that would have otherwise had reductions based on historic changes in the funding formula between SFYs 2011 and 2012. The Governor would have relied on Extraordinary Needs Grants alone, which are determined based on a combination of free and reduced-price meal eligibility and the taxable property value per student within a district. The Governor would have grown these Extraordinary Need Grants over time, making them the only form of aid based on community characteristics by SFY 2034. In the interim, the Governor’s proposed Hold Harmless Grants would prevent a drop in assistance to any communities based on the current formula during the next budget biennium, and then ramp down assistance for districts that do not receive the same amount of assistance or more in Extraordinary Needs Grants over time during the next decade.

Instead of eliminating forms of aid based on community-level indicators, the House would retain those aid mechanisms and reinsert another mechanism used in past iterations of the formula. The House would retain Relief Aid based on the concentration of free and reduced-price meal eligible students within a community. The House would also re-establish Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid in the education funding formula, which is aid based only on the taxable property value per pupil within a community.[21] The budget proposed by the House would also retain Stabilization Grants at 85 percent of their original levels, reducing the contribution from $157 million to about $134 million.

Extraordinary Needs Grants would also be included in the House’s formula, but would start at a much higher level in SFY 2024. While the Governor would set these grants at a maximum of $650 per student and increase that cap by 50 percent each biennium over ten years, the House would begin SFY 2024 with a maximum grant of $3,000, which would be adjusted upward annually by 2 percent each year, as would all other parts of the education funding formula besides Stabilization Aid. Finally, the House would also introduce a Hold Harmless Grant for SFYs 2024 and 2025 to ensure no community received less funding in SFY 2024 than in SFY 2023 due to the formula changes. Because of the House’s other community-level supports, the Hold Harmless Grants would be much smaller than the Governor’s Hold Harmless Grants, falling from an estimated $87.1 million in SFY 2024 to $638,000 statewide.[22]

Education Freedom Accounts

When it was enacted, the current State Budget established the Education Freedom Account (EFA) program. This program permits parents who have children that are not enrolled in school districts to apply for and receive the Adequate Education Aid funding that a school district would have received to support that student in an EFA. Money in this EFA may be used by parents for a wide variety of education expenses, including tuition and fees at a private school, Internet services and computer hardware primarily used for education, non-public online learning programs, tutoring, textbooks, school uniforms, certain therapies, and other expenses approved by a State-recognized approved scholarship organization.[23]

To be eligible, a student must be a state resident eligible for public school from a household with an annual household income at 300 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or below at the time of application. However, that student’s household does not need to maintain incomes below that level to continue to be enrolled and receive funding through the EFA program.[24]

The Governor’s office and the Department of Education reported that $9.0 million was spent on Education Freedom Accounts in SFY 2022, while the cost was $14.7 million in SFY 2023, totaling $23.7 million during the biennium. The Governor’s budget proposal as introduced would appropriate $59.7 million in total for SFYs 2024 and 2025, or 151.9 percent more than the amount spent in the first two years of the EFA program.

The House reduced appropriated funding by $20 million in total, reallocating those funds to other purposes. However, eligible families will still be able to receive EFAs, as they are not subject to budget limitations and are granted out of the Education Trust Fund, which is backstopped by the General Fund, even if the budget line for EFAs is exceeded.

The House also eliminated the Governor’s proposed expansion of EFA eligibility. The Governor’s proposal would have kept the 300 percent of federal poverty guidelines threshold requirement for the family at the time of application, but also made certain students household incomes up to 500 percent of the federal poverty guidelines eligible if they faced defined circumstances, such as if they are homeless, in foster care, have a disability, are an English language learner, are eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, are a victim of documented and repeated bullying, or have a documented manifest educational hardship. The House, however, removed these proposed eligibility expansions in its version of the State Budget, retaining the existing eligibility standards.

Medicaid Direct Certification, Funding for Free and Reduced-Price Meal Students

The House budget includes a provision that would shift the State to relying on Medicaid enrollment information to determine which students are eligible for free and reduced-price school meals. Students typically provide written paperwork to show their eligibility for free and reduced-price school meals, or they are automatically enrolled through direct certification from their participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The House budget would require the State to attempt direct certification of students based on information collected through Medicaid enrollment. Overall Medicaid enrollment among children in New Hampshire is much higher than SNAP or free and reduced-price school meal enrollment, suggesting Medicaid direct certification may lead to more students who are already eligible for free and reduced-price school meals to be enrolled in the program.[25] This change would also boost funding for local public schools with students who would be newly recognized as eligible.

The House appropriated $30 million to fund potential changes in free and reduced-price school meal enrollment.

Additional Funding for Charter Schools

The Governor’s budget proposal includes language that would increase the per pupil State grant to public charter schools on top of the aid received through the State’s education funding formula, by $141.28 to a total of $3,552.28 for each student. The House’s proposal includes a significant boost to charter school funding relative to both current policy and the Governor’s proposal, increasing per pupil aid to $5,000 per student above the State’s regular education funding formula allocations.

School Building Aid

As well as increasing the regular budget lines for State aid to local public schools for building construction, the Governor proposed adding $75 million in one-time aid for local school construction at the end of SFY 2025. The Governor’s budget would create a separate State Building Aid Fund within the Education Trust Fund for this purpose. The House removed these proposals from its version of the State Budget, resulting in $75 million fewer dollars devoted to school building aid of any form relative to the Governor, but retaining the increase in school building aid in the regular State Budget appropriation line as allocated by the Governor; that budget line would increase by $34.7 million (66.7 percent) over the amounts enacted in the current State Budget as passed in 2021.

Under the House proposal, public charter schools would also become eligible for school building aid previously restricted to district public schools.

Education Trust Fund Tax Revenues

The House also altered the Governor’s proposed changes to the manner in which revenues from the two primary business taxes are split between the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund. Currently, the Business Profits Tax primarily funds the General Fund, but the revenue estimated to be generated by 1.5 percentage points of its 7.5 percent rate is directed to the Education Trust Fund. The Business Enterprise Tax rate is also split, with the first 0.5 percentage points of the Business Enterprise Tax rate dedicated to the Education Trust Fund, leaving 0.05 percentage points of the 0.55 percent rate for the General Fund.[26]

The Governor proposed simplifying the split, requiring 35 percent of the revenue from the Business Profits Tax flow to the Education Trust Fund, and the rest to the General Fund. The Business Enterprise Tax would have the same split, with 35 percent of revenue flowing to the Education Trust Fund and the balance going to the General Fund.

The House would keep the same concept of splitting revenues in a different manner than currently used, but it would reduce the percentage of revenue flowing to the Education Trust Fund substantially. Rather than 35 percent as the Governor proposed, only 22.5 percent of each of the two business taxes would flow to the Education Trust Fund. Certain expenses that draw on the Education Trust Fund currently, including school building aid, tuition and transportation aid, and certain forms of targeted special education aid, would instead draw on the General Fund in the House proposal.

Despite these shifts in expenses to the General Fund, the reduction in revenue to the Education Trust Fund would quickly drain its current surplus. The House estimated the Education Trust Fund would end SFY 2023 with a surplus of $183.3 million; by the end of SFY 2025, that surplus would be transformed into a $42.6 million deficit. The money that would have gone to the Education Trust Fund, and remained in that Fund for education-related purposes, instead would flow to the General Fund in the House budget, and would largely be deployed for other purposes through General Fund appropriations.

Per State law, the Education Trust Fund is backstopped by the General Fund.[27] As a result, changing the funding flows does not change the actual payments for education aid to communities, individuals, or schools in any of the forms that are established in statute. Altering the split between the Education Trust Fund and the General Fund changes the flow of dollars, and how these resources are accounted for in State documentation, but separate changes to law would be required to alter the amount of aid flowing to recipients.

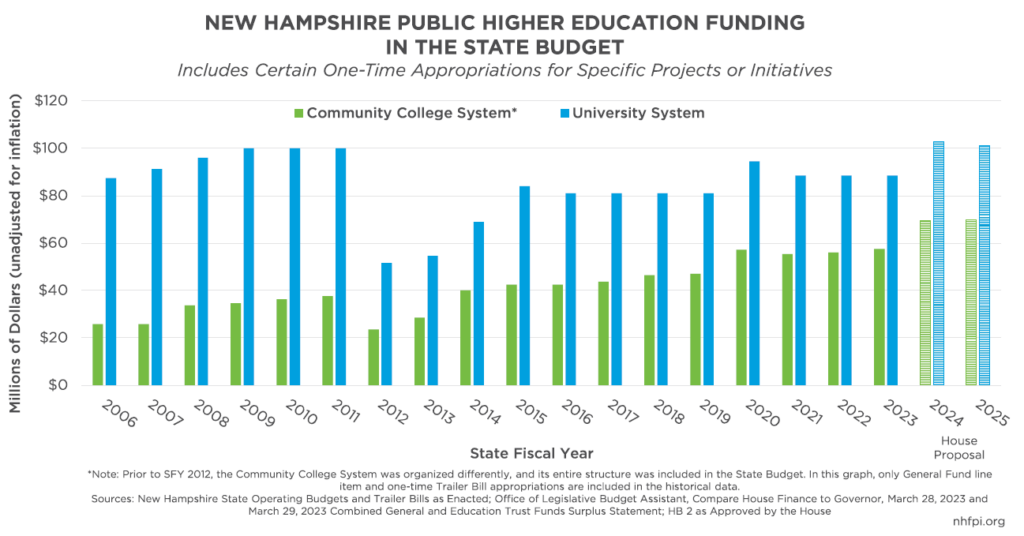

Higher Education

The House made some limited changes to the higher education funding policies proposed by the Governor. At the Community College System of New Hampshire, the House added targeted funding and policy changes by:

- boosting funding for the dual and concurrent enrollment program, expanding the potential scope for students relative to the Governor’s proposal by including more opportunities for coursework and fewer restrictions on fields of study, and adding $1.5 million in appropriations

- expanding workforce credential programs with a $2 million appropriation

- enhancing accessibility and affordability of postsecondary education through the Promise Program, with an appropriation of $6 million during the biennium

- establishing a Math Learning Communities Program designed to engage high schools in teaching children advanced mathematical and quantitative reasoning courses, with a $400,000 appropriation

The House also reduced the appropriation to support renovations at the Whittemore Center Arena at the University of New Hampshire from $8 million to $6 million. Instead, the House appropriated another $2 million to the General Fund operating support for the University System in SFY 2025 above the Governor’s proposed levels.

Other Education Policy Changes

Relative to the Governor’s State Budget proposal, the House made a few key additional changes related to Education policy and funding, including:

- eliminating the Governor’s proposed student debt relief program

- retaining the ability of Community College System employees to have access to the New Hampshire Retirement System, which the Governor had proposed restricting

- defunding the New Hampshire Commission on Civics, which is required to produce a textbook on New Hampshire’s constitution and government, and had been granted a $2 million appropriation by the Governor

- removing the Governor’s proposed Computer Science Education Program, which would have incentivized both experts in the field to become computer science educators and existing educators to get credentials

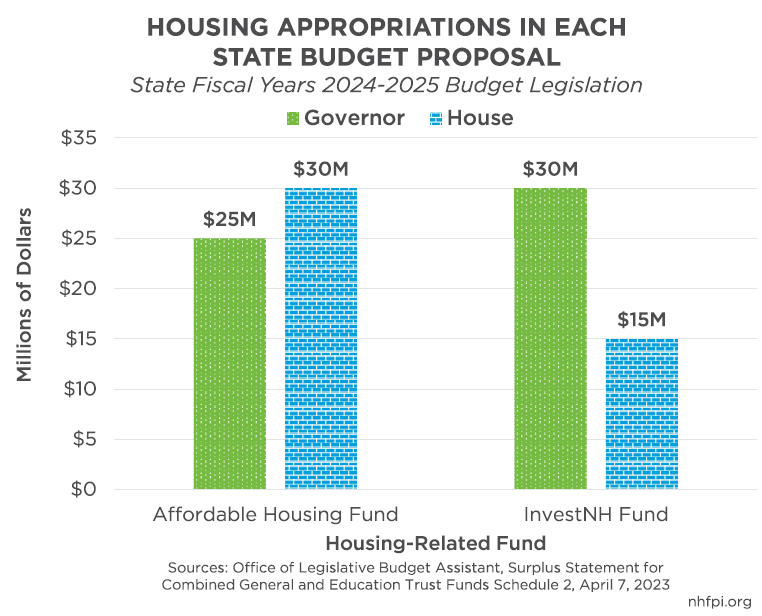

Housing

Both the Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s approved budget included language allocating resources to the Affordable Housing Fund and both establishing and contributing to the InvestNH Fund.

The Affordable Housing Fund, administered by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority, provides grants and low-interest loans for the construction, rehabilitation, or acquisition of housing affordable to families and individuals with low or moderate incomes. State funds contributed to the Affordable Housing Fund may be used in conjunction with federal funds and operates in compliance with federal rules, although these dollars can provide more flexibility than other federal resources.[28] The Governor proposed adding $25 million to the Affordable Housing Fund, and the House voted to increase that contribution to $30 million.

Using resources provided by the federal American Rescue Plan Act, the Governor previously established the InvestNH program to support housing development in the state. Approved in May 2022, the Governor used $100 million in relatively flexible federal American Rescue Plan Act funds to create the InvestNH program, which includes:[29]

- $50 million for developers of multifamily rental housing units in the state to cover funding gaps in projects that are already permitted or under construction

- $10 million for the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s programming to support capital projects, including resources that may flow through the Affordable Housing Fund

- $30 million to municipalities to provide an incentive of $10,000 per multifamily housing unit permitted within municipal borders less than half a year after the application for construction was submitted

- $5 million to support municipal efforts to establish or update local zoning rules and regulations, granted to municipalities for the use of hiring third party entities to review regulations and understand housing options with the goal of adding housing stock

- $5 million to aid municipalities in demolishing buildings that are vacant or dilapidated, with the goal of adding new housing stock

None of the above funds are General Funds, and the InvestNH program does not currently exist in State law. The Governor and the House both proposed statutory changes that would establish the program, and both proposed relatively limited language, leaving considerable discretion of the Department of Business and Economic Affairs to establish the details of the program within the broad goals of accelerating the approval and construction of workforce housing. However, the House limited grants to be paid from the newly-established InvestNH Fund to only go to municipalities, rather than also to developers as the Governor had proposed. Effectively, that would limit the existing program to the municipal incentives, zoning code reform supports, and demolition aid, and not permit any future funding to flow to developers for capital projects. This change would not impact the scope of the Affordable Housing Fund’s activities.

The Governor proposed a $30 million contribution to the InvestNH Fund, while the House proposed a contribution of $15 million to its more narrowly-targeted version that would solely support municipalities.

The House’s budget proposal would permit the Supreme Court to establish a land use review docket in Superior Court that would have authority to hear appeals related to decisions from local zoning boards, municipal planning boards, or historic or conservation commissions. The Superior Court would add an associate justice to be the presiding justice for this docket.

The House’s State Budget did not include the Governor’s proposed Historic Housing Preservation Tax Credit.

Transportation

Relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, the House would bolster funding for transportation by making a one-time appropriation of $10 million in General Fund SFY 2023 surplus to the Highway Fund. This transfer reflects an ongoing revenue shortfall in the Highway Fund that the Legislature has repeatedly backfilled with surplus from the General Fund. While revenues to the General Fund are based on key revenue sources that are more likely to grow relative to inflation, including tax revenues based on percentages of corporate profits, business compensation, restaurant meals or property sales, and interest, dividend, and distribution income, the Highway Fund is primarily funded by motor fuels tax revenue, which is a fixed dollar amount of 22.2 cents per gallon for gasoline and diesel fuel, and vehicle registration fees.[30] In the last three budget cycles, legislators have contributed General Fund surplus to the Highway Fund to temporary address this structural imbalance, including approximately:

- $13.9 million in General Fund contributions to the Highway Fund in the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget[31]

- $4.0 million in General Fund contributions to the Highway Fund and diverting $8.4 million in Department of Safety operations revenue that may have lapsed to the General Fund to directly flow to the Highway Fund in the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget[32]

- $50.0 million in General Fund dollars to the Highway Fund, and permitting certain General Fund dollars made in an earlier appropriation for structurally deficient bridge work to lapse to the Highway Fund in the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget[33]

These repeated appropriations do not include potential cost offsets associated with one-time, off-budget appropriations of General Funds to transportation-related projects, such as $66.0 million in General Funds to local governments for road and bridge work appropriated in SFY 2022, which followed $36.8 million in General Funds for these same purposes in SFY 2017 and $10.4 million specifically for municipal bridges in SFY 2018, as well as $20.0 million for structurally deficient State bridges in SFY 2018.[34]

The House’s decision to continue General Fund appropriations to the Highway Fund, and more favorable Highway Fund revenue estimates, would support about $4.8 million in additional support for purchasing new and replacement equipment at the Department of Transportation relative to the Governor’s budget proposal. The House’s budget proposal would also add nearly $1.9 million in General Funds to access additional available federal investment funding for urban and rural transit operations through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The House would add more Highway Fund revenue for local governments, due to enhanced Highway Fund revenue estimates. The House also would modify the Governor’s proposed revolving fund for over-length, over-width, and over-height vehicles, which would collect revenues from the permit fees for those vehicles, to include over-weight vehicles. Finally, the House removed from the Governor’s budget a suspension on the limitation on the percentage of total Highway Funds that can go to the Department of Safety; the House would keep the limitation in place for the biennium.

Other Initiatives

The House’s version of the State Budget proposed key changes to the Governor’s policy initiatives, and also made State programmatic and operational changes beyond responding to the Governor’s proposals.

New Hampshire Retirement System Changes

Relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, the House proposed three changes to the New Hampshire Retirement System, all with significant one-time or ongoing costs.

The House proposed a one-time contribution of $50 million to the unfunded accrued actuarial liability in the New Hampshire Retirement System. The total unfunded liability totaled nearly $5.7 billion in June 2022, and reported projections suggest this one-time investment may save $105 million over a twenty-year period.[35]

The House also appropriated an annual contribution of $25 million each year, totaling $50 million during the biennium, by adding a separate House bill to the State Budget. This appropriation would fund retirement contributions and support subsequent benefits policy changes for approximately 1,824 State and local fire and police employees who were not vested into the New Hampshire Retirement System prior to 2012, when significant changes were made to retirement benefits; these employees would have been vested prior to 2013.[36] The change would also define “vested” explicitly in State law with regard to State and local employees relative to the New Hampshire Retirement System. This policy change would also set the maximum retirement contribution amount for State and local police and fire employees to $125,000 annually, an increase from the maximum possible of $120,000 under current law.

The House also added a one-time supplemental payment to the retirement benefits of State and local police and fire employees who have been retired for more than 15 years. For those employees retired between 15 and 20 years, the increases would be based on the number of years an employee has been retired, rising to a maximum of $900. For former employees who have been retired for more than 20 years, the supplement would total $3,000. Both allowances would not be permitted to boost total annual retirement benefits for any employee to over $100,000 per year, under the House’s proposal. The estimated cost of these supplemental payments totals $9 million, which would be funded from SFY 2023 surplus in the House’s budget proposal.

Licensing Reform Overhaul

The House removed most of the proposed licensing reforms that were attached to the Governor’s State Budget. The Governor had proposed eliminating 34 licenses, as well as eliminating eight governing boards associated with industry licensing or regulation and shifting parts of the duties of others to the Office of Professional Licensure or Certification (OPLC).

The House removed almost all these proposed changes. The House would eliminate the licenses for athlete agents, itinerant vendors, and hawkers and peddlers. Regulatory oversight of professional bondsmen was shifted to OPLC.

Certain other boards and governing entities would be substantially modified or have parts of their responsibilities shifted to OPLC as well, including the:

- Assessing Certification Board, which would shift to an advisory role

- Real Estate Appraiser Board

- State Board of Auctioneers

- Allied Health Professionals, which would have its oversight and operational duties relative to other boards in specific health industries shifted to OPLC

- Boxing and Wrestling Commission, which would also be expanded from three to five members

- Electricians’ Board

- Genetic Counselors Governing Board

- Pharmacy Board, which would also have its membership reduced from seven to five

Food Waste Mitigation

The House added new provisions to the State Budget that would regulate food waste. Any person generating more than one ton of food waste per week would face new regulatory requirements after February 2025.

Food waste would be required to be separated from other forms of solid waste and could not be deposited in a landfill or incinerator, and would be sent to an alternative facility with capacity to accept the food waste, when such a facility is within 20 miles of the person generating the waste.

The Department of Environmental Services would also be appropriated $98,000 in SFY 2025 for a new waste management specialist position.

Enhanced Food Assistance Through Access to School Meals

The House voted to expand access to food for children at school. The House’s budget includes language that would increase the income cap for eligibility in nutrition programs at school. Currently, the cap is 185 percent of the federal poverty level for reduced price meals, or about $45,991 for a family of three, and 130 percent for free meals. The House proposal would expand eligibility for free meals to all students with household incomes below 300 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $74,580 for a three-person family. This expansion would enhance access to food for more students, as about 17.2 percent of families had incomes lower than $50,000 in 2021, while nearly one-third of families had incomes below $75,000 that year.[37]

This eligibility boost is separate from free and reduced-price school meal eligibility as defined by the State’s education funding formula, however. While the State would provide funding to support school districts providing more meals for free, it would not provide additional funds through the education funding formula.

Changes to Other Provisions

The House made other key changes to the Governor’s State Budget proposal, including:

- reducing the amount of funding devoted to the construction of a new State prison for men in the State Budget from $50 million to $10 million, and emphasizing the need to select a location

- deleting the Governor’s proposed State Historic Sites Fund and shifting the funding structure for existing operations related to historic sites

- appropriating $4.8 million to State building maintenance and renovation work, as well as for the use of temporary space associated with moving State offices between buildings

- removing funding of $15 million for a new legislative parking garage, instead setting aside $25 million in revenue to fund an appropriation in a separate piece of legislation

- adding funding of $2.6 million and re-establishing a total borrowing authority cap of $30 million for the Winnipesauke River Basin Control program

- eliminating the newly-proposed Northern Border Alliance Program, which under the Governor’s proposal would reimburse and make grants available to State, county, and local law enforcement for working to reduce crime and illicit activities within 25 air miles of the Canadian border

- permitting funding related to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to be used for grants as well as loans, and expands the purposes for which these funds can be used

- reducing funding for polychlorinated bi-phenyl contamination mitigation and research by $5 million, reducing the Governor’s proposed $6 million to $1 million

- establishing a Cyanobacteria Mitigation Loan Program to assist municipalities and non-profit associations

- eliminating the Governor’s proposed Office of Regulatory Review, Reduction, and Government Efficiency within the Department of Business and Economic Affairs

- modifying the Department of Corrections and National Guard recruitment and retention programs

- eliminating an appropriation of $1 million to NH Public Television

- requiring the Governor’s State Budget Trailer Bill transmission to the Legislature to be publicly posted by February 15 deadline

Revenue Projections and Tax Policy Changes

In the process of developing its own version of the State Budget, the House produced a set of revenue estimates. The House also altered the Governor’s proposed tax policy changes, retaining the Communications Services Tax and adding revenue during the biennium while accelerating the planned repeal of the Interest and Dividends Tax, which would significantly reduce available revenue during the next budget biennium.

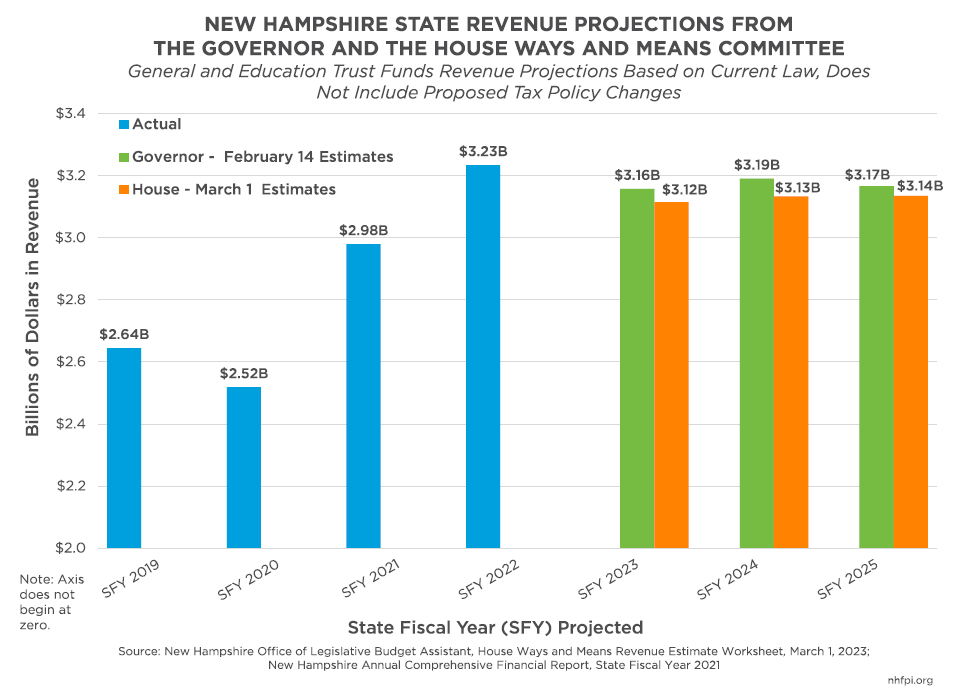

Revenue Projections

The Governor proposed revenue projections that suggest relatively limited economic growth, and the House generally agreed with those revenue projections. However, the House was more pessimistic, projecting lower revenues from the combined business taxes as well as the Real Estate Transfer Taxes compared to the Governor. Both the Governors’ and the House’s revenue projections are relatively static, with revenues falling due to reduced Interest and Dividends Tax income and total revenues behaving similarly in SFYs 2023, 2024, and 2025.

The Governor’s revenue projections show an approximately $67.8 million loss due to the previously-enacted phaseout of the Interest and Dividends Tax, which would also reduce revenues in future biennia. The Governor also anticipated combined Business Profits Tax and Business Enterprise Tax revenues would decline between SFYs 2023 and 2025, and both Meals and Rentals Tax and Tobacco Tax revenues would be flat across the next biennium. The Governor estimated growth in the Real Estate Transfer Tax would stall, but that higher levels would be maintained.

The House’s revenue estimates for the budget biennium project about $131.0 million less for the General and Education Trust Funds than anticipated by the Governor across SFYs 2023, 2024, and 2025. The House was more optimistic than the Governor relative to receipts from the Meals and Rentals Tax. However, the House projected that Real Estate Transfer Tax revenues would slow considerably, and that the revenue from the two primary business taxes would drop further than the Governor projected. The Committee was also less optimistic with regard to revenues from the Tobacco Tax and the Utility Property Tax.[38]

While the Governor’s revenue estimates suggested no revenue growth, the Governor’s plan does envision that, by the end of the next State Budget biennium, an additional $181.4 million in surplus General Fund revenues would be available to deposit into the Rainy Day Fund. The House’s State Budget plan, however, envisions adding only $40.8 million to the Rainy Day Fund by the same June 30, 2025 end date.

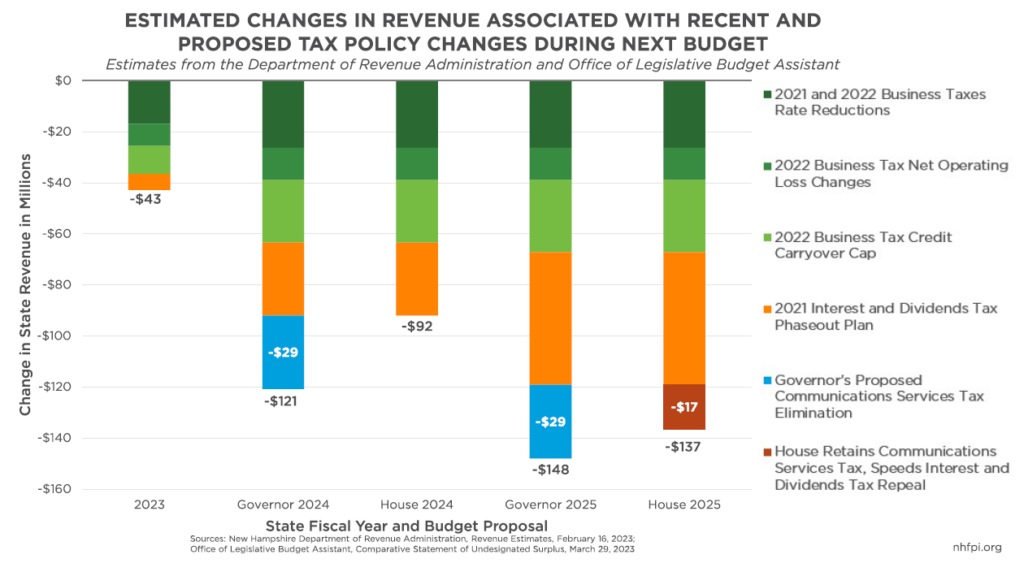

Tax Policy Changes

The Governor’s State Budget proposal included the elimination of the Communications Services Tax, which is charged on certain two-way communications services, including both landline and cellular phone bills. The Governor would eliminate this tax starting on July 1, 2023. As a result of that elimination date, the Governor did not project this tax would bring in any revenue during the State Budget biennium with this policy change, resulting in a loss of approximately $57.8 million in General Funds during those two years.

The House retained the Communications Services Tax in its proposal as part of its effort to fund changes in the retirement system expected to cost $25 million per year. That increased revenue collected during the SFYs 2024 and 2025 biennium by $57.8 million.

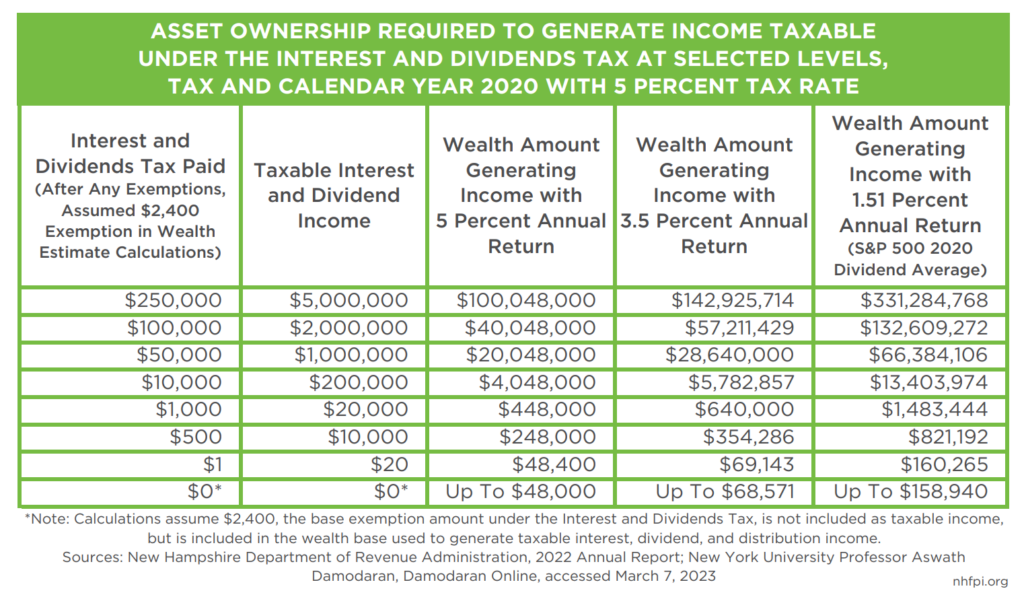

However, the House would accelerate the repeal of the Interest and Dividends Tax. Under current law, the Interest and Dividends Tax is being phased out with successive rate reductions, and is due to be eliminated entirely in 2027. The House would eliminate this tax two years early, in 2025. Official State estimates suggest that this proposed accelerated elimination would cost the State Budget $17.4 million during this biennium. Critically, it would also reduce revenues by $82 million during the next biennium, more than offsetting expected revenue gains associated with the change to retain the Communications Services Tax.

The Interest and Dividends Tax collects revenue from income generated by wealth. Taxed income does not include money collected from the sale of assets, such as capital gains, or through salaries and wages. Information published by the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration indicates more than half of the tax revenue was paid by households with more than $200,000 in interest, dividend, and distribution income in Tax Year 2020. The underlying wealth required to generate $200,000 of income taxable under the Interest and Dividends Tax would range from $4 million to $13.4 million, assuming rates of return on investments range from 1.51 percent, which was the average S&P 500 stock dividend yield in 2020, to a more robust 5 percent annual return rate. Economic modeling also indicates that more than nine of out every ten forgone tax dollars would benefit the top 20 percent of households by income, and more than half of the tax reduction would benefit the top 1 percent of households.[39]

These tax policy changes follow substantial recently enacted reductions in revenue. Estimates from the Department of Revenue Administration indicate that tax policy changes to the State’s two primary business taxes and to the Interested and Dividends Tax that took effect in SFYs 2021 and 2022, not including tax rate reductions and policy changes prior to SFY 2021, would have reduced General and Education Trust Funds revenues by $91.9 million in SFY 2024 and $119.1 million in SFY 2025.[40] The additional tax policy changes proposed would further reduce revenue for services.

Conclusion

The next State Budget will fund public services during an economically uncertain time, with both the State government and Granite State families and individuals facing higher costs for the same goods and services and an economy that continues to be unsettled following the COVID-19 pandemic. The House’s budget proposal includes substantial service increases that could help families weather an economic storm while reducing revenue available for policymakers to fund these services in the subsequent State Budget cycle.

The House proposed an increase in total expenditures relative to the Governor’s proposal and the current State Budget, changing funding for a majority of State agencies relative to the Governor’s recommended levels. The largest increases, at the Department of Health and Human Services and within the New Hampshire Retirement System, reflect some of the key changes proposed by the House.

The budget approved by the House includes key provisions that could effectively help bolster New Hampshire’s workforce and support financially strained Granite Staters. Expansions of Medicaid to maintain enrollment for parents who have recently given birth and their children, as well as for certain immigrant women and children legally residing in New Hampshire, would help draw down federal funds to support both these potentially vulnerable residents and the state’s economy. The two-year extension of the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program would help ensure tens of thousands of adults with low incomes in the state would continue to have access to health coverage, largely funded by the federal government, although a two-year extension presents less certainty than the current five-year extension or a proposed permanent reauthorization. Boosts in Medicaid reimbursement rates may help health care providers attract and retain staff to deliver needed services. Supports for housing construction could also enable more workers to move into New Hampshire, or between regions within the state to pursue job opportunities, while easing upward pressure on housing costs for residents.

Additionally, the House budget would enhance food security for children and income security for the families seeking care for them. The Medicaid direct certification provision and the expansion of food assistance eligibility likely would lead to more children being identified and served food for free at school with fewer paperwork requirements, while a higher income threshold means a greater percentage of students, who may still face acute financial resource constraints at home, would be eligible should they seek to enroll in these food assistance programs. For families with children younger than school ages, enhanced access to child care subsidies could help offset a major, and sometimes prohibitive, cost that can create tradeoffs in employment and other key decisions.

The proposed changes to the education funding formula made by the House, following the Governor’s proposed reconsideration of key parts of the formula, presents a continuing opportunity to re-examine the State’s methods of funding local public education. The House largely rejected the Governor’s simplification of the formula, instead proposing additional targeting of aid to communities with higher needs. The House proposed layering in more mechanisms, rather than fewer, to target this aid, bolstering existing methods with more resources while retaining or reinserting older parts of prior iterations of education funding formulae with altered parameters. The House’s targeting of aid would change the outcomes for this biennium and would not embrace the Governor’s proposed ten-year transition to a simpler model, instead seeking to ensure that multiple aid-targeting methods are used in concert.

The House deployed more resources than the Governor for operations during the biennium despite having lower revenue estimates. The House accomplished this feat by reducing planned contributions to the Rainy Day Fund relative to the Governor, diverting revenue from the Education Trust Fund to the General Fund, raising more revenue through retaining the Communications Services Tax the Governor had proposed eliminating, and making accounting decisions that provided a more complete picture of expected federal resources that would be accessed during the biennium.

However, the House also potentially set up a key fiscal constraint for the next budget biennium. The accelerated repeal of the Interest and Dividends Tax, which generates the majority of the revenue it collects from individuals and households who likely have millions of dollars in assets and higher incomes, will substantially reduce General Fund revenues available during the SFYs 2026-2027 biennium. If other revenue sources slip in an uncertain economic environment, then the elimination of a major State tax revenue source will jeopardize the ability of the State to fund needed and expanded services.

Public policy can help build an inclusive, equitable, and sustainable economy. Assistance to individuals and families with low incomes can both permit those households to make ends meet and effectively boost economic growth. Both direct services from the State government and assistance to local communities and organizations providing these services can help support a strong recovery and help ensure it reaches all Granite Staters. As the state continues into a period of potential economic uncertainty, the next State Budget will need to wisely and purposely deploy sufficient resources to successfully help foster an equitable and inclusive economy for all New Hampshire residents.

Endnotes

[1] For more information on the economic impacts on different policies stimulating the economy, see NHFPI’s March 14, 2023 blog Households with High Incomes Disproportionately Benefit from Interest and Dividends Tax Repeal and NHFPI’s February 8, 2021 Issue Brief Designing a State Budget to Meet New Hampshire’s Needs During and After the COVID-19 Crisis.

[2] Read NHFPI’s March 27, 2023 Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025 for explanations of the differences between the Governor’s State Budget proposal and the current State Budget as enacted for SFYs 2022-2023. Unless otherwise noted, the source material for this Issue Brief includes material collected by the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant for the SFYs 2024-2025 Operating and Capital Budget and SFY 2024-2025 Revenues.

[3] These comparable amounts include the appropriations allocated in the State Budget’s Trailer Bill in the current State Budget, in the Governor’s proposed Trailer Bill, and in the House’s Trailer Bill. For example, the Governor’s Trailer Bill, which is House Bill 2 for the 2023 Session as Introduced, included nearly $684.3 million not included in House Bill 1 for the 2023 Session as Introduced, the Operating Budget Bill, which appropriates $14.88 billion. In the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget as enacted, changes outside of the State Budget lines in House Bill 1 totaled about $192.6 million, and were about $161.2 million in the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget.

[4] For national context, see the Pew Charitable Trusts January 11, 2023 research article Elevated Inflation Raises Risk of Fiscal Stress for States.

[5] For more information, see NHFPI’s December 6, 2022 presentation Federal Pandemic-Related Funding in New Hampshire: Impacts, Opportunities, and Benefits.

[6] Learn more about State revenues since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in NHFPI’s January 17, 2023 presentation New Hampshire State Revenues and the Economy and NHFPI’s April 19, 2023 presentation The New Hampshire Economy and State Revenues.

[7] Other Trailer Bill appropriations are included in these figures, based on the department or agency they are assigned to by the Trailer Bill language.

[8] These agencies, not shown in the graphic, include the Department of Justice (+$0.602 million), the Department of Agriculture, Markets, and Food (+$0.555 million), the Police Standards and Training Council (+$0.15 million), the Department of Fish and Game (+$0.131 million), the Tax and Lan Appeals Board (+$19,500), the Secretary of State (+$4,000), and the Department of Environmental Services (-$0.736 million).

[9] See NHFPI’s July 2022 publication Long-Term Services and Supports in New Hampshire: A Review of the State’s Medicaid Funding for Older Adults and Adults with Physical Disabilities.

[10] April 2023 figures reported by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Monthly Caseload Report. For historical enrollment data, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography report.

[11] For more information on the Granite Advantage program, see NHFPI’s January 2023 Issue Brief The Effects of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire.

[12] See Senate Bill 263, 2023 Session.

[13] For more information, see the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute January 2023 analysis Permanent Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Option, Maternal Health Infrastructure Investments in 2022 Year-End Omnibus Bill.

[14] See House Bill 282, 2023 Session, which has identical language to this proposed State Budget section.

[15] The House shifted funding for Sununu Youth Services Center operations from House Bill 2, the Trailer Bill, to House Bill 1, the Operating Budget Bill.

[16] For more information on Child Care Scholarships, see the September 2021 New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services presentation NH Child Care Scholarship Program 101, the Department’s Family Assistance Manual, the NH Connections Child Care Scholarship webpage, and the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy brief Why Interstate Child Care Scholarship Policy Choices Matter in the Upper Valley, March 7, 2023.

[17] See the Department of Health and Human Services’ Family Assistance Manual, Section 935, for details.

[18] Income data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2021, Table S1901 for New Hampshire.

[19] See the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy brief Why Interstate Child Care Scholarship Policy Choices Matter in the Upper Valley, March 7, 2023 and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan For New Hampshire FFY 2022-2024.

[20] For more details, read NHFPI’s March 27, 2023 Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025.

[21] To learn more about prior uses of Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid in the State’s education funding formula, see NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[22] For a more detailed analysis of each component of the changes in the education funding formula relative to current law as proposed by the House and the Governor, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, Comparison – Adequacy Grants, April 6, 2023.

[23] See NHFPI’s August 2021 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023.

[24] See NHFPI’s August 2021 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023.

[25] See Medicaid Enrollment Data compiled by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and 2022 – 2023 Free Reduced School Lunch Eligibility Rate by District published by the New Hampshire Department of Education. SNAP enrollment by age provided in the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services monthly caseload reports.

[26] See RSA 77-A:20-a and RSA 77-E:14.

[28] For more information on the Affordable Housing Fund, see the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s Other Financing Programs webpage and the Authority’s New Hampshire Affordable Housing Fund Fact Sheet.

[29] For more information on the InvestNH program, see the fiscal item approved by the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Executive Council that approved the program dated April 6, 2022 and the supporting policy framework provided by the Department of Business and Economic Affairs dated April 29, 2022.

[30] For more on the motor fuels tax and Highway Fund revenues, see NHFPI’s May 2017 Revenue in Review resource and the New Hampshire Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for SFY 2022, page 119.

[31] See NHFPI’s July 2017 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019.

[32] See NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[33] See NHFPI’s August 2021 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023.

[34] See Chapter 227, Laws of 2017, Chapter 162, Laws of 2018, and Chapter 338, Laws of 2022.

[35] Information from the New Hampshire Treasury Department, General Obligation Bond 2023 Series A and B Information Statement, page 79, and information provided from the New Hampshire Municipal Association analyzing projections from the New Hampshire Retirement System.

[36] Information provided by the New Hampshire Retirement System to the House Finance Committee on March 27, 2023.

[37] Income data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2021, Table S1901 for New Hampshire.

[38] For summaries of State revenue projections from both the Governor and the House Ways and Means Committees, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, House Ways and Means 3-1-23 Estimates and Governor 2-14-23 General Fund and Education Trust Fund Estimates.

[39] To read more about the Interest and Dividends Tax, see NHFPI’s March 2023 blog Households with High Incomes Disproportionately Benefit from Interest and Dividends Tax Repeal.

[40] To see the estimates from the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, see the Department’s presentation to the House Ways and Means Committee from February 16, 2023.