The next two-year State Budget will fund State-supported services during a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The needs of New Hampshire residents will likely be fast-changing and difficult to anticipate, as public health risks associated with the virus may be volatile and economic forecasts are subject to substantial uncertainty. Significant federal support to individuals and families, as well as delayed demand for goods and services, may help boost the economy significantly during the coming State Budget biennium. However, Granite Staters with low incomes and limited resources have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 crisis, and the recovery may not fully reach those residents without intentional public policy support. The services funded during the next State Budget biennium will be key for helping ensure New Hampshire’s recovery from this crisis is robust and equitable.

The Governor’s budget proposal would provide additional funding for several key areas of health and social services in New Hampshire, including harnessing federal and state funds to support behavioral and mental health services. Certain social services would be allocated fewer dollars under the Governor’s proposal, including employment-related supports for child care, and transportation funding would also decline in aggregate. Local public education would see significantly fewer funds than under the current State Budget, reflecting both reduced enrollment and the decision to not repeat one-time grants to communities with less taxable property wealth per student and more children from families with low incomes. One-time aid to municipalities would also not be repeated under the Governor’s proposal, leading to an aggregate decline in general revenue to cities and towns relative to the current State Budget. Proposed tax policy changes would also significantly reduce revenue for services during the budget biennium, and the most significant revenue losses would occur in subsequent years.

This Issue Brief examines key components of the Governor’s State Budget proposal for the next two fiscal years, comparing the Governor’s proposed funding levels to those in the current State Budget and levels requested by State agencies in the fall of 2020. The Issue Brief also reviews revenue projections and proposed changes to State tax policy contained in the Governor’s State Budget proposal.[i]

The Topline Changes

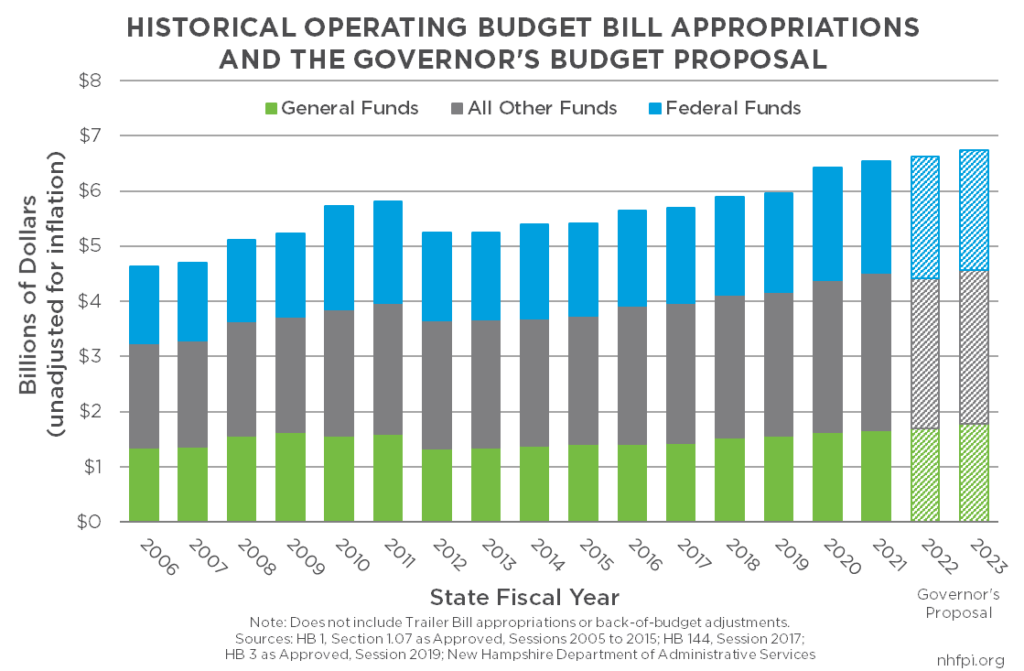

The Governor’s proposed budget for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2022 and SFY 2023 would continue the trend of increasing aggregate appropriations from budget cycles since the SFYs 2012-2013 State Budget. The Governor’s proposal, net of interagency transfers related to information technology services, would appropriate $13.36 billion during SFYs 2022 and 2023, a 3.1 percent increase from the comparable SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget total allocated in the final operating budget bill.[ii] The total State Budget grows by 1.3 percent from the amount appropriated in SFY 2021 to the SFY 2022 proposal, and 1.9 percent from SFY 2022 to SFY 2023.

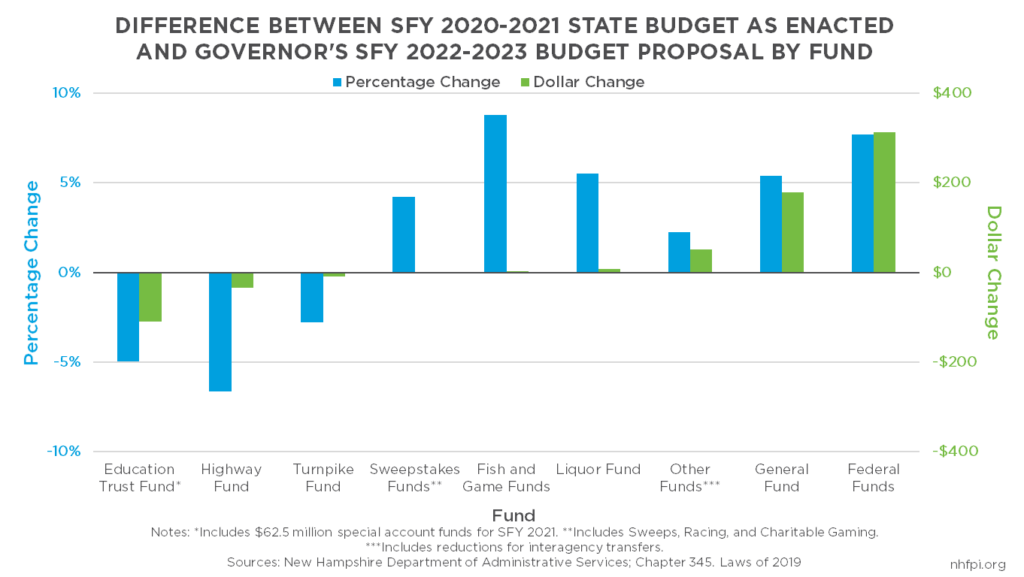

Not all funding areas would expand evenly under the Governor’s State Budget proposal. Of the State Budget’s major funds, which are the legal structures organizing State Budget appropriations, the Governor budgets for the largest dollar increase in Federal Funds. The Governor anticipates that transfers from the federal government to fund State Budget expenditures would increase $312.0 million (7.7 percent) in the upcoming biennium relative to the amounts anticipated by the current State Budget as passed in 2019. The current State Budget did not anticipate COVID-19-related aid, and the Governor’s budget proposal also does not appear to include new, unrestricted aid from the federal government related to COVID-19.

The Governor’s budget would expand the General Fund by $178.4 million (5.4 percent) relative to the prior biennium, constituting the second largest increase in dollars among the major funds. The Governor anticipates General Fund appropriations will be higher than originally budgeted during SFY 2021, which would lead to slightly lower General Fund appropriations in SFY 2022 than in SFY 2021. However, incorporating estimated lapses, which are planned amounts of underspending at State agencies, the Governor projects General Fund expenditures will be larger in SFY 2022 than in SFY 2021 and will grow again in SFY 2023.

The Governor would appropriate fewer dollars from two key funds related to transportation, the Highway Fund and the Turnpike Fund. The Highway Fund would decline by $34.7 million (6.6 percent) under the Governor’s budget proposal relative to the amounts budgeted in 2019 for the current biennium, while the Turnpike Fund would decline by $9.6 million (2.8 percent). These allocations likely reflect expected changes in revenue from taxes on gasoline sales and reduced traffic through Bureau of Turnpikes tolls.

The Governor also would appropriate less than the current State Budget to the Education Trust Fund, which holds the funding for grants for local public education to school districts. The total reduction in the Education Trust Fund would be $109.9 million (4.9 percent). This decline reflects both reduced enrollment, as grants are allocated on a per pupil basis, and the decision to not continue the targeted aid provided in the current State Budget to communities with less relative taxable property wealth and more students from low-income families.

Expenditure by Category of Government Services

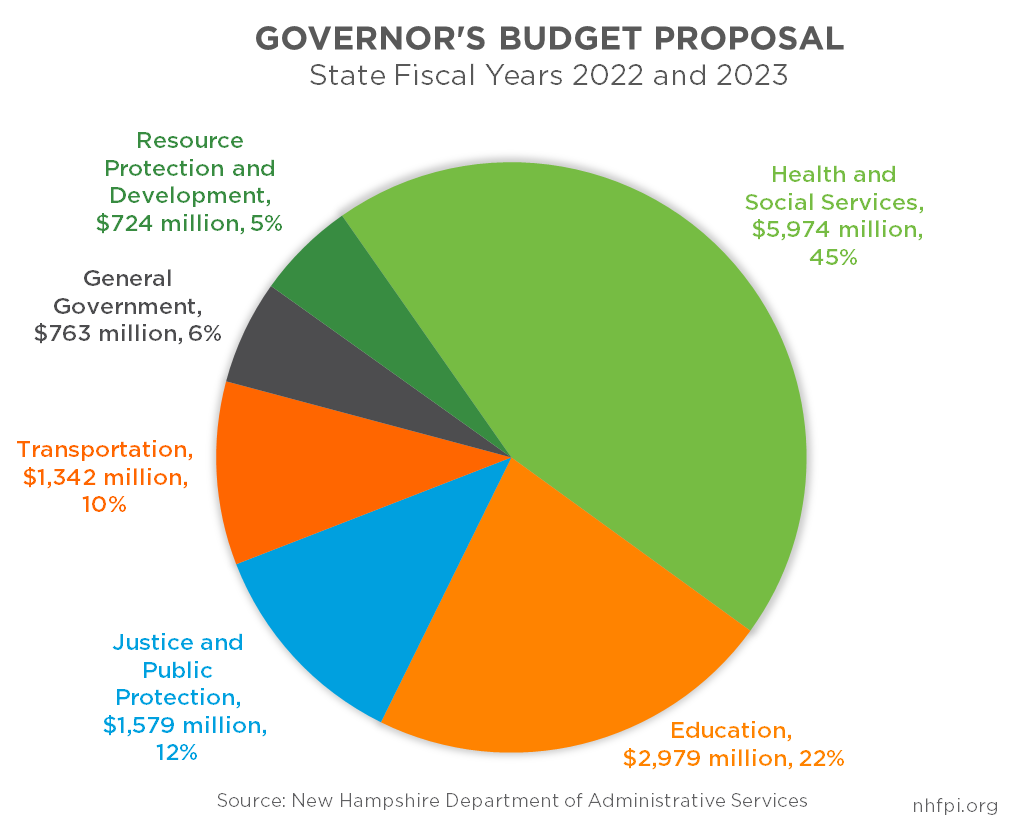

All State Budget expenditures are allocated to one of six categories based on the service area of each department. These six categories are designed to cover all areas of State government operations, and include General Government, Justice and Public Protection, Resource Protection and Development, Transportation, Health and Social Services, and Education.

The Governor’s budget proposal would, as the current State Budget does, allocate the plurality of funds to Health and Social Services, with Education receiving just over a fifth of appropriations. Justice and Public Protection would receive the next largest appropriation, with nearly $1.6 billion (11.8 percent) appropriated during the biennium, including General Fund and Federal Fund appropriations as well as appropriations from all other funds. Transportation would follow with $1.3 billion (10.0 percent), General Government with $763 million (5.7 percent), and Resource Protection and Development with $724 million (5.4 percent).

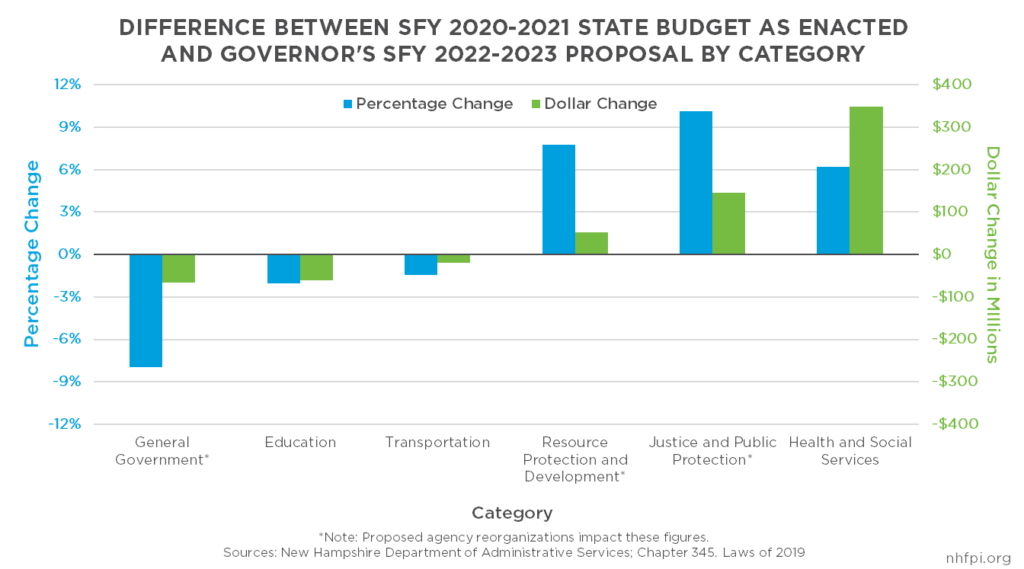

The largest dollar increases, relative to the current State Budget as passed, would go to Health and Social Services, which would grow as a percentage of the entire State Budget. Health and Social Services, which is almost entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services budget, would rise by $349.1 million (6.2 percent) and total slightly under $6.0 billion during the biennium, likely reflecting greater and more acute needs during and following the COVID-19 crisis, retention of enhanced Medicaid reimbursement rates, and both increases in support for services from both federal funding and the State’s General Fund.

Education, the next-largest category in the State Budget, would see a lower level of funding from the current biennium’s appropriations under the Governor’s proposal. The majority of expenditures in this category are driven by the Adequate Education Grants paid to local governments to fund public education on a per pupil basis; this category also includes funding for the University and Community College Systems and operations at the New Hampshire Department of Education, the Police Standards and Training Council, and the Lottery Commission, which generates revenue to support the Education Trust Fund. The Governor’s proposed reduction in funding to local communities comprises a significant portion of the $61.4 million (2.0 percent) decline in funding in the Education category, relative to the current biennium’s budget as enacted in 2019.

General Government would see the largest dollar decline, $66.0 million (8.0 percent) relative to the current biennium. A significant portion of this decrease, about $17.6 million, appears to be in State retiree health insurance benefits. Another component of this shift is due to the Office of Strategic Initiatives, formally the Office of Energy and Planning, moving in part to the newly-proposed Department of Energy and in part to the Department of Business and Economic Affairs. Both of those moves shift allocations from General Government to Justice and Public Protection, which would grow overall by $145.1 million (10.1 percent), and Resource Protection and Development, which would grow $52.0 million (7.7 percent) compared to the current State Budget in total. These two categories would also see funding increases at other agencies, including the Department of Environmental Services, the Department of Safety, and New Hampshire Employment Security.

Overall, the largest increase in funding would be in Health and Social Services, and the largest decrease would be in Education, after adjusting for agency reorganization shifts. These two expenditure categories in the State Budget, which together account for about two-thirds of all State Budget expenditures, experience the most significant movement of dollars in the Governor’s proposal relative to the current State Budget.

Proposed Changes by State Agency

State agency-level analysis provides additional insight into the changes proposed by the Governor’s budget. The previous analyses comparing budget categories and funds provide comparisons between the two-year budget proposed by the Governor and the two-year State Budget approved by policymakers in 2019. The analysis of State agency budgets in this section compares the SFY 2021 budget, with any adjustments or additional expenditure authorizations made since the State Budget was approved, with the Governor’s proposed budget for SFY 2022.

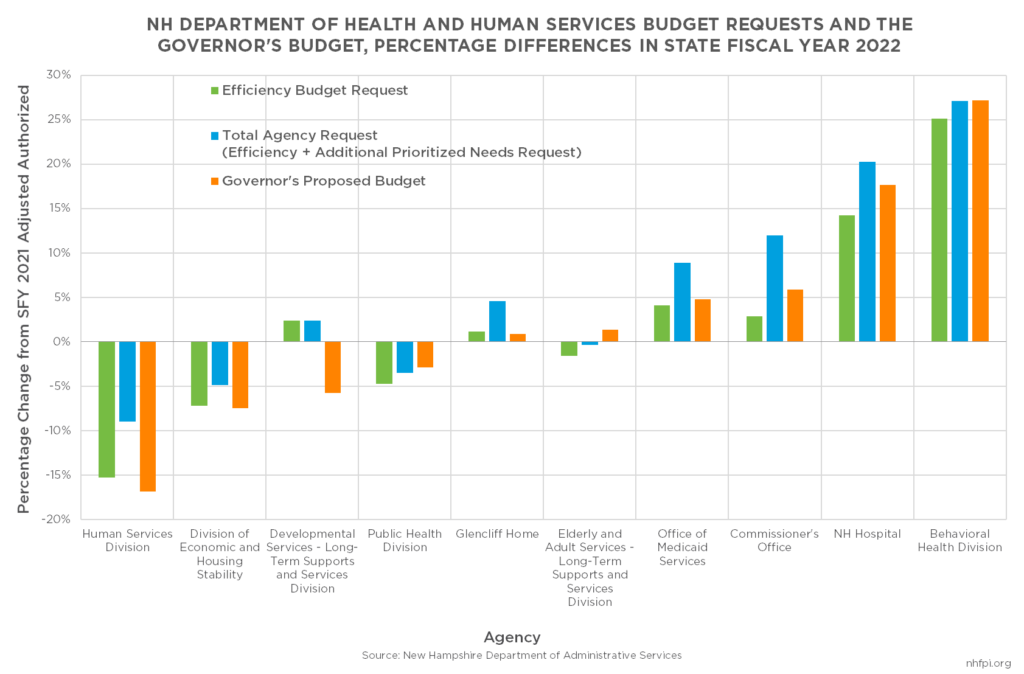

State agency-level comparisons also offer the opportunity to compare the Governor’s SFY 2022 proposed allocations to the levels State agencies submitted in their October 2020 budget requests. The requests included two levels: an Efficiency Budget request, based on targeted expenditure levels provided by the Governor’s office in August 2020, and an Additional Prioritized Needs request, which identifies any priorities that could not be funded under the Efficiency Budget expenditure target. Together, the Efficiency Budget and the Additional Prioritized Needs constitute the Total Request.

Comparisons to the agency requests allow for some understanding of prior agency expectations around programs that were previously planned to change, whether there was a planned reorganization of duties within or between agencies, or agency expectations regarding service needs. However, during the COVID-19 crisis, expected needs have been changing quickly, and agency forecasts from October may not accurately reflect expectations in February, when the Governor’s budget proposal was released.

The year-over-year comparisons of funding, contrasting current SFY 2021 levels with SFY 2022 as proposed by the Governor, permits a comparison of continuity or changes in services that would happen next year, with adjustments that policymakers have already made for SFY 2021 incorporated into the comparison.

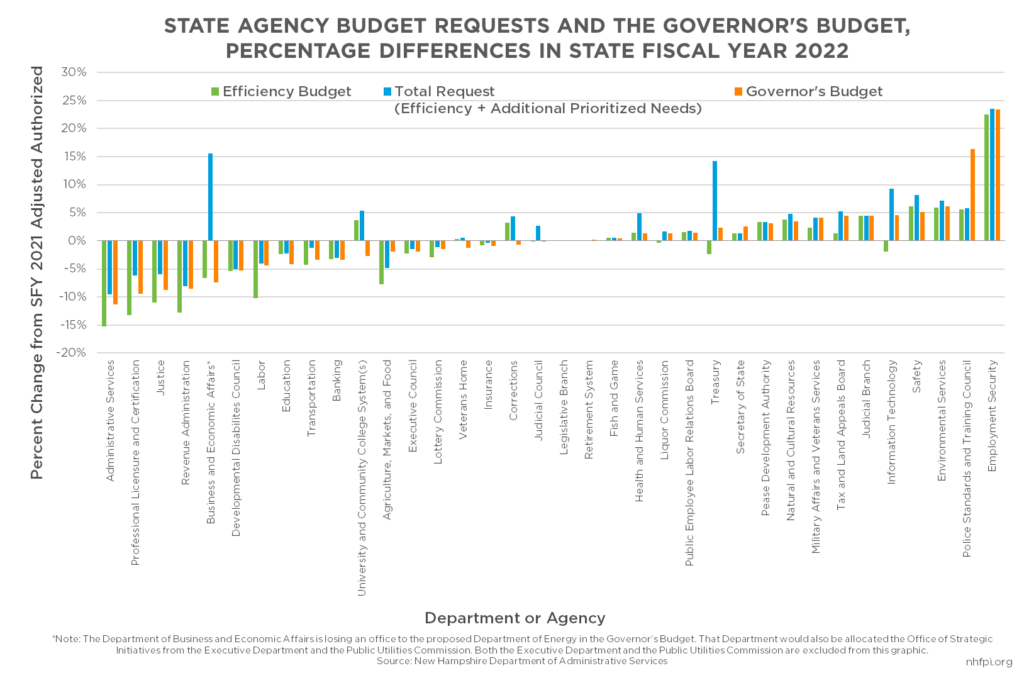

The percentage changes in State agency funding levels show 26 of the 36 agencies with comparable appropriations across the two years would have funding levels within five percent of their SFY 2021 appropriations in the Governor’s budget proposal. This analysis does not adjust for the Governor’s proposed agency reorganizations, and as such excludes the Governor’s proposed Department of Energy, the Public Utilities Commission (which would be absorbed into the new Department of Energy), and the Executive Department (which currently includes the Office of Strategic Initiatives in whole; the Governor’s proposal would divide the Office into two components and allocate them to other agencies). Slightly less than half, 17 of 36, agencies would see a funding increase, while 18 of 36 would see an aggregate decrease, and the Legislative Branch would be level-funded.

The largest percentage decreases from SFY 2021 to SFY 2022 would be in the Department of Administrative Services (-11.4 percent), the Office of Professional Licensure and Certification (-9.4 percent), the Department of Justice (-8.8 percent), the Department of Revenue Administration (-8.5 percent), and the Department of Business and Economic Affairs (-7.4 percent). All these agencies would be appropriated funding levels higher than their Efficiency Budget and lower than their total request under the Governor’s budget proposal, except for the Department of Business and Economic Affairs. The decrease at the Department of Administrative Services appears to be driven primarily by decreases in appropriations for State employee retiree health insurance benefits, although there are proposed reductions across many operations within the Department. The Office of Professional Licensure and Certification would undergo a reorganization in the Governor’s proposal, including transferring the Controlled Drug Prescription Health and Safety Program from the Office to the Department of Health and Human Services. Reduced appropriations to the Justice Department appear to be primarily due to a reduction in federal funding anticipated through the Victims of Crime Act.[iii] At the Department of Revenue Administration, the Governor would allocate less to software, following the Department’s implementation of a new software system, and reductions in other areas across the agency. About half of the decline at the Department of Revenue Administration is due to a more than 54 percent reduction in funding for the Low and Moderate Income Homeowner’s Property Tax Relief program; this program’s use has declined over time even while property tax levies have increased overall, likely reflecting a lack of awareness about, and updates to, the program.[iv] Reductions at the Department of Business and Economic Affairs appear in the marketing expenses budgeted for the Division of Travel and Tourism, with budgeted expenditures dropping from SFY 2021 appropriations and appearing to nearly match SFY 2020 actual expenditures. The Governor’s proposal would also implement similarly-structured reductions in the budgeted funding for highway rest areas and workers compensation within the Department of Business and Economic Affairs, and would also eliminate the Bureau of Film and Digital Media.

The largest relative percentage increases in funding to State agencies would occur in New Hampshire Employment Security (23.4 percent), the Police Standards and Training Council (16.4 percent), the Department of Environmental Services (6.1 percent), the Department of Safety (5.2 percent), and the Department of Information Technology (4.6 percent). New Hampshire Employment Security would be primarily boosted by federal funds, and both program services and software would see appropriations increase substantially. Both staff and contracts would increase at the Police Standards and Training Council, and the Department of Environmental Services would draw more loans and grants from the Drinking Water and Groundwater Trust Fund for use by the Waste Management Division, including to address contaminants.[v] Significant funding shifts between budget lines within the Department of Safety yield relatively little change in overall funding, with most of the increase due to boosts in federal assistance related to COVID-19.[vi] The Department of Information Technology would receive a substantial increase in its budget for software.

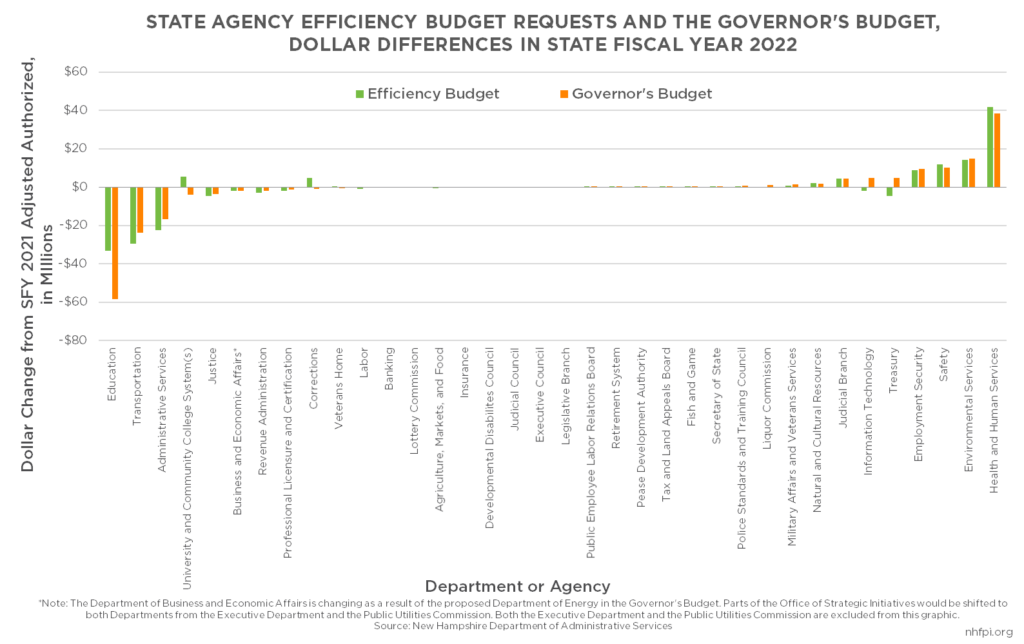

Examining the changes in dollars of agency funding levels between authorized SFY 2021 amounts and the Governor’s proposed SFY 2022 reveals similar shifts, but also where smaller percentage changes can reflect relatively large dollar changes at the largest State agencies. The agencies with the largest decreases in the number of dollars appropriated between the two years would be the Department of Education (-$58.5 million), the Department of Transportation (-$23.8 million), the Department of Administrative Services (-$16.9 million), the combined funding levels for the University System and Community College System (-$3.9 million), and the Justice Department (-$3.8 million).

The largest dollar increases year-over-year would be in the Department of Health and Human Services ($38.3 million), the Department of Environmental Services ($14.8 million), the Department of Safety ($10.0 million), New Hampshire Employment Security ($9.3 million), and the Treasury Department ($4.7 million).

These increases and decreases in dollar amounts appropriated reflect changes at some of the largest agencies, including some overlap with the agencies that would see large percentage changes in funding. Many smaller agencies are dwarfed by others in the dollar-level changes analysis, however, despite distinct and important roles, which emphasizes the value of both comparisons.

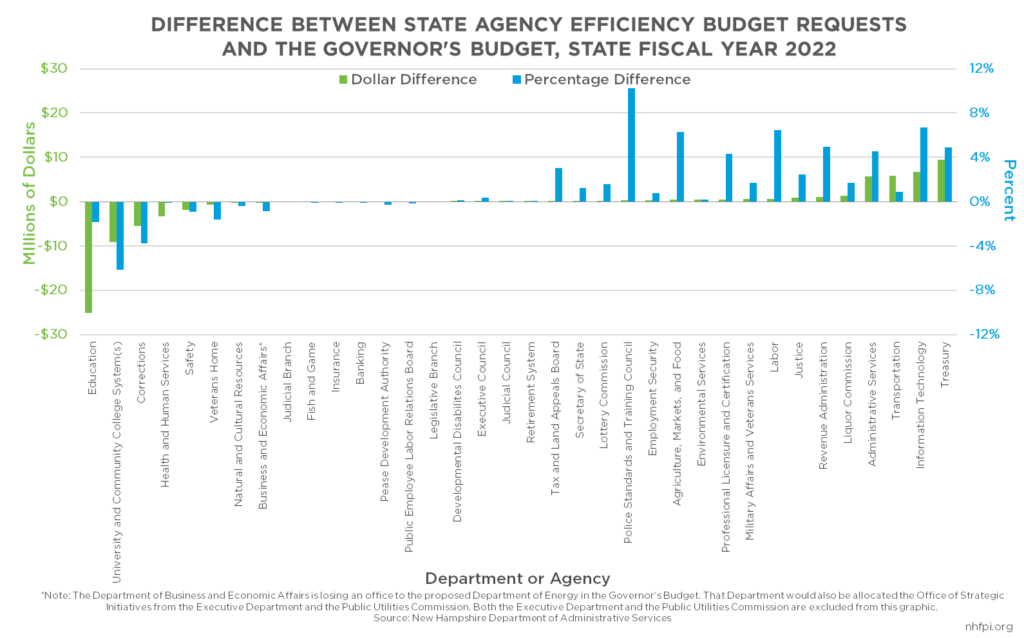

The Efficiency Budget requests provide additional context for the Governor’s proposal. Although the Efficiency Budgets are based in part on spending targets provided by the Governor’s office, deviations from the Efficiency Budgets in the Governor’s proposal provide insights into shifts in prioritization, different evaluations of need, or new information collected by the Governor’s office during the budget creation process.

While some smaller agencies would see significant percentage changes from their Efficiency Budget requests in the Governor’s budget proposal, the largest dollar shifts from the Efficiency Budget requests for SFY 2022 would be in a few key agencies. The largest dollar decreases for SFY 2022 relative to the Efficiency Budget requests in the Governor’s proposal would be in the Department of Education (-$25.1 million), the combined University and Community College Systems (-$9.2 million), the Department of Corrections (-$5.6 million), the Department of Health and Human Services (-$3.4 million), and the Department of Safety (-$1.8 million). The largest increases relative to the Efficiency Budget requests would come in the Treasury Department ($9.5 million), the Department of Information Technology ($6.7 million), the Department of Transportation ($5.8 million), and the Department of Administrative Services ($5.7 million).

Agency Reorganizations

Agency-level comparisons are complicated by the Governor’s proposed reorganizations of several key agencies. The Governor proposed similar reorganizations in both his 2017 and 2019 budget proposal, both shifting key components of departments into reformed entities and making smaller agencies administratively attached to larger ones to seek organizational efficiencies.[vii]

The Department of Energy

The Governor has proposed the creation of the Department of Energy, which would be the result of combining several existing organizations within State government. The new Department of Energy would be created from the energy-related components of the Office of Strategic Initiatives (OSI), the re-established Office of Offshore Wind Industry Development, and the Public Utilities Commission (PUC).

OSI currently resides in the Executive Department, which houses the Governor’s office, and was previously called the Office of Energy and Planning before being renamed as a result of the Governor’s 2017 budget proposal. OSI would be split into its energy and planning components, with the energy staff shifting to the new Department of Energy, and the planning staff moved to the new Office of Planning and Development in the Department of Business and Economic Affairs.

The PUC, currently a separate entity, would be an independent entity administratively attached to the Department of Energy. Certain powers and duties would be split between the new Department of Energy and the PUC, and other powers would be shared between the two entities in law. The State’s Site Evaluation Committee would expand from nine members to ten, including the newly created Commissioner of the Department of Energy, and the Site Evaluation Committee would be administratively attached to the new Department.

The new Department would be responsible for New Hampshire’s ten-year State Energy Strategy, negotiating with the Power Authority of the State of New York and with Canadian officials to contract for purchase of electricity, and advocating for New Hampshire’s interests before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and other national and regional entities.

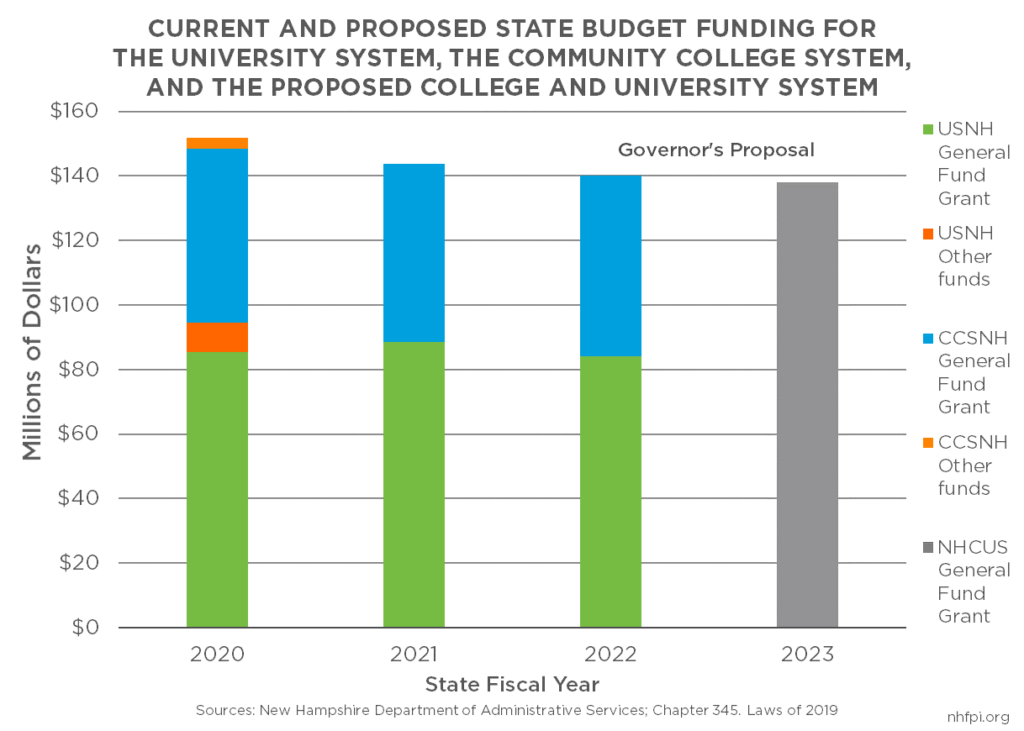

The University System and the Community College System

The Governor’s budget proposal would combine the University System of New Hampshire and the Community College System of New Hampshire. These entities are currently incorporated separately in statute and have separate grants of General Fund money to support their operations. There are four schools within the University System of New Hampshire: the University of New Hampshire, Plymouth State University, Keene State College, and Granite State College, all of which offer four-year degrees.[viii] The Community College System of New Hampshire includes seven colleges with 12 locations: White Mountains Community College, River Valley Community College, Lakes Region Community College, NHTI – Concord’s Community College, Great Bay Community College, Manchester Community College, and Nashua Community College.[ix]

The Governor’s budget would first combine the two Boards of Trustees into a single, fifteen-person body, all appointed by the Governor. Five members would be drawn from nominations by the four-year institutions in the system, five members drawn from the two-year institutions, and five members selected by the Governor without nominations. The Board would also include eight ex-officio members that would include elected state officials, heads of state departments, and the Chancellor of the combined University and Community College System.

This new, combined Board would be required to elect the Chancellor of the combined University and Community College System and, by January 2022, recommend legislation to combine the two systems into one by no later than July 2023. Before that time, the combined Board would be required to govern the two systems under existing statutes.

The Governor’s proposed budget would combine the budget lines for the Community College System and the University System starting in SFY 2023, which begins July 1, 2022. The Governor would appropriate less money to the two systems overall in each year of the budget biennium than in the current State Budget. The current State Budget includes higher levels of general operating funding, as well as additional one-time, purpose-specific appropriations, than the budget proposed by the Governor.

Health and Human Services

With the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacting the health and economic well-being of many Granite Staters, increased needs for health and social services over the next two years renders this already key category of State-supported services even more critical. This category is almost entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) budget, which is the largest State agency and includes several critical programs, including Medicaid, the Food Stamp Program, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, all of which include significant amounts of federal funding support. Medicaid, which provided health coverage for more than 214,000 Granite Staters at the end of January 2021, totaled approximately $2.1 billion in expenditures in SFY 2020, with more than half of those expenditures funded by the federal government.[x]

The Governor’s budget proposal would increase funding to the DHHS in each year of the biennium. Total funding in the Governor’s proposal, relative to the current State Budget as passed in 2019, would increase $360.9 million over two years. About $174.6 million of that increase would be General Fund dollars, and $180.0 million would come through an increase in Federal Funds. The Governor would retain a recent increase in provider Medicaid reimbursement rates, most of which are funded with General Fund dollars matched by federal funding, which would result in corresponding increases in each funding source. However, several federal grants are also anticipated to expand in the Governor’s budget proposal.

Within the budget of the DHHS are separate agencies, including divisions, offices, and institutions. These agencies each operate significant portions of the services provided by the DHHS, but vary in size substantially. While the DHHS budget would increase overall under the Governor’s budget proposal, not all areas of the DHHS budget would increase, with both significant funding shifts and changes to services contributing to funding changes.

Human Services, Child Protection, and Child Care

The largest percentage decreases in funding at the agency level within the DHHS come in the Human Services Division, which would see a decline in funding by $38.8 million (16.8 percent) in SFY 2022 under the Governor’s proposal relative to the SFY 2021 authorized amount. The Efficiency Budget request was also lower, by $35.2 million (15.3 percent). A key change in this division comes within the Division of Children, Youth, and Families, which is accounted for within the Human Services Division in the State Budget’s organization. Approximately $52.5 million that would likely have been in the Human Services Division budget for Out of Home Placement and Community Based Services appears in the Office of Medicaid Services budget as part of an apparent reorganization of line items. However, the Child Development Program in the Human Services Division also saw about $15.2 million less allocated during the Governor’s proposed budget biennium than in the current State Budget, with the reductions concentrated in employment-related child care funding. These dollars do not appear to be offset elsewhere by funding increases. As the public health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis recede and more workplaces open, child care will provide a critical service, enabling more Granite Staters to return to work.[xi]

The Governor would also establish an Emergency Services for Children, Youth, and Families Fund to support DHHS efforts to avoid the removal of children from families and support reunification when no other supports or services are available to meet immediate needs. Parental reimbursement requirements for certain charges associated with children involved with DHHS programs or evaluations would also have timelines changed, and certain charges could be waived by the DHHS.

In an appropriation separate from the DHHS budget, the Governor proposed adding $500,000 to the Internet Crimes Against Children Fund during the biennium.

Economic and Housing Stability

The Division of Economic and Housing Stability also saw a decrease relative to SFY 2021 adjusted authorized funding levels. This decrease of $9.0 million (7.4 percent) appeared to stem in part from a reduction in funding for employment services, as well as a decline in expected payments to clients in the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program. The Governor’s proposal would increase grant funding for the Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled program. Available affordable housing, both for rent and purchase, was severely constrained prior to the COVID-19 crisis; during the pandemic, housing prices have increased substantially and inventory has declined, leading to even fewer options for people with low and moderate incomes. Income losses have led many New Hampshire households to fall behind on rent and housing payments, which may lead to increased need for economic and housing assistance.[xii]

Developmental Services

Although the DHHS requested an increase in funding in its Efficiency Budget for developmental services, the Governor’s budget appears to reduce funding in SFY 2022 relative to the amount authorized for SFY 2021. Comparing the current State Budget biennium to the Governor’s two-year proposal, the Governor would increase funding by $26.8 million (4.2 percent). However, funding in SFY 2022 would be $9.6 million less than the originally enacted SFY 2021 amounts. For comparison, the current State Budget increased funding by $127.8 million (25.0 percent) over the SFYs 2018-2019 State Budget. A new funding mechanism may be affecting the presentation of these figures in the State Budget, but available materials indicate the Governor’s proposal would be a reduction in funding.

Medicaid Funding

Funding would substantially increase in the Office of Medicaid Services, which includes the budget lines for the State’s contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations.[xiii] Medicaid services are funded with federal matching dollars, which are included in the State Budget, resulting in increases in State General Fund support for Medicaid being matched dollar-for-dollar by corresponding increases in federal funds in most cases. Funding would increase a total of $58.7 million (4.8 percent) between the currently authorized amount for SFY 2021 and SFY 2022 as proposed. Some of this increase would likely be due to Medicaid enrollment changes, and a significant portion is due to the shift of Medicaid-related budget lines from the Human Services Division to the Office of Medicaid Services. Significant funding lines would be reorganized within the Office of Medicaid Services under the Governor’s budget proposal.

The Governor’s budget would also implement a policy change associated with funding the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program for adults aged 19 to 64 years old with low incomes. The Governor proposes using revenue from the Medicaid Enhancement Tax to support the State’s required portion of funding for this program.[xiv]

Additionally, the Governor’s budget would limit public funding for certain reproductive health care but maintain compliance with the State’s participation in the federal Medicaid program. The Governor’s proposed budget would also require the DHHS to provide quarterly reports on Medicaid costs, payments, and other information as required by the Governor.

Mental Health Services and New Hampshire Hospital

The proposed increase in funding at New Hampshire Hospital would be driven primarily by an increase in the budget for Acute Psychiatric Services. The $15.3 million (17.6 percent) increase between authorized SFY 2021 totals and the proposed SFY 2022 budget would be supported in part by a General Fund increase, and would also be supported by agency income and transfers from other State agencies. The Governor also proposes setting aside $17.25 million in any federal assistance for revenue replacement or budget relief that comes to the State to construct a 60-bed forensic psychiatric hospital on the grounds of New Hampshire Hospital. If federal relief does not arrive by the end of December 2021, the Governor would authorize use of other State funds or borrowing to construct such a facility. This facility would be considerably larger than the 25-bed facility envisioned in the current State Budget.

The Governor would also appropriate $1.5 million to support veterans struggling with mental health and social isolation, which could be used by veterans’ organizations to perform safety upgrades or other capital improvements to their facilities. Separately, the Governor would appropriate an additional $1.5 million for mental health and social isolation services for older adults.

Substance Use Disorder Services

The Division of Behavioral Health Services would see an increase in funding of $24.8 million (27.2 percent) between the authorized SFY 2021 appropriation and the SFY 2022 amounts proposed by the Governor. While there would also be increases to the Bureaus of Children’s Behavioral Health and Mental Health Services within the Division, $21.8 million of the increase occurs in the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services. The increase would be driven almost entirely by a boost in funding through the State Opioid Response Grant from the federal government, although the Governor’s budget would also increase General Funding to the Bureau by a smaller amount.

Additionally, the Governor’s budget proposal would transfer and re-establish the Controlled Prescription Drug Health and Safety Program within the DHHS, shifting it from the Office of Professional Licensure and Certification.[xv]

Older Adults

The Governor proposes that, during the budget biennium, the income eligibility threshold for adult clients of the Social Services Block Grant program would increase annually. That increase would correspond to the cost-of-living adjustments made to social security benefits under federal law. As noted previously, one of the Governor’s proposed $1.5 million allocations would target help to older adults struggling with mental health and social isolation.

The Governor’s budget envisions an increase in Medicaid services appropriations for nursing home and in-home supports, but would fund this support with a $47.5 million (19.8 percent) increase in county obligations and corresponding federal matching funds, offset by a significant reduction in State General Fund support, likely meaning the Medicaid increase would be funded in whole or part by county property tax payers.

State retiree health insurance benefits appear to also see a $17.6 million decrease in funding, under the Governor’s proposal. In addition, the Governor would eliminate the Senior Volunteer Grant Program, which provides stipends and covers expenses for volunteers in senior companion and foster grandparent programs.[xvi]

Appropriation for Financial Review Recommendations

In the Governor’s proposal, the DHHS would receive approximately $10.0 million to implement certain recommendations from the financial review conducted by the management consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal. These funds would support the streamlining of certain agency operations to support greater efficiency and accountability, according to the statutory language proposed by the Governor. The language also identifies certain transformation projects over a four-year period, although the funding would be available only through the State Budget biennium, and could be supported by applicable federal funds and any gifts, grants, or donations for this purpose. Alvarez & Marsal began working with the DHHS during 2020 to conduct a strategic assessment of DHHS operations, produce cost savings, increase efficiency, improve service delivery, and consider the operational and financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.[xvii]

Family Leave Insurance

The Governor proposes establishing the Granite State Family Leave Plan, which would be a required plan for State employees and a voluntary plan for other entities, including businesses and individuals, seeking to join. State employees would participate with the State paying the costs, and an unspecified transfer of funds would occur to set up the program. Non-state employers may join under certain conditions, and may choose the extent to which their employees are required to contribute to the cost of participation. The program would be overseen by the Department of Administrative Services, which would contract with a private accident or life insurance carrier to run the program.

Eligible employees would receive 60 percent of their average weekly wage for a maximum of six weeks per year, with a cap on the wage calculation for higher income earners. Employees would be eligible as the result of the birth of a child or placement of a foster or adopted child within the past year, a serious health condition of a family member, or for certain military-related care. The health condition of the employee would not be cause of eligibility, although caring for ill children, parents, or a spouse would trigger eligibility.

The insurance program’s stabilization would be supported in part by diverting Insurance Premium Tax revenues associated with this family medical leave insurance. The Governor’s proposal would also offer a tax credit against the Business Enterprise Tax for participating businesses for up to 50 percent of the premium paid by a sponsoring employer.

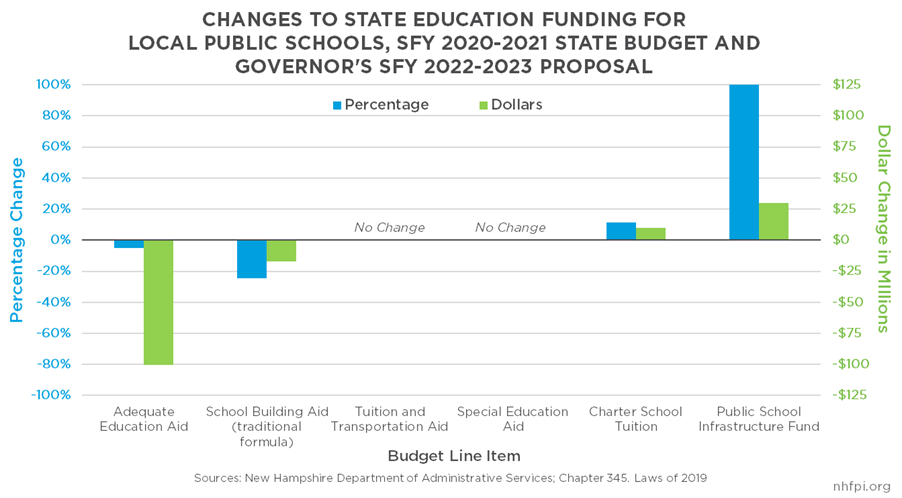

Local Public Education

The Governor’s budget proposes significant reductions in funding for local public education relative to the current biennium. Several key changes would be due to both anticipated lower public school enrollment and the discontinuation of funding targeted at communities with more children from low-income families and lower taxable property values per student.

The Governor anticipates the Education Trust Fund would have a projected $32.2 million surplus at the end of the budget biennium, and indicates the surplus would leave the State better prepared than before to weigh the recommendations of the Commission to Study School Funding. That Commission, which provided its report and recommendations in December 2020, constituted the most recent in a series of ongoing efforts to address inequities and disparities in the State’s effort to support an adequate public education at the local level.[xviii]

The Governor’s budget adds funding for local school infrastructure and public charter schools relative to the current State Budget. The Governor’s proposal would also enable schools that would otherwise have been disadvantaged by the effects of changes to free and reduced-price school meal programs during the pandemic to access expanded resources through the education funding formula, but otherwise does not alter the underlying structure for funding most local public schools.

Adequate Education Aid

The primary mechanism through which State funding is supplied to local public schools for supporting education is Adequate Education Aid. The majority of this assistance comes in the form of per pupil Adequate Education Grants, which include base grants of $3,786.66 per full time student in SFY 2022, under current law, with additional per pupil funding for students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, students receiving special education assistance, and English language learners.[xix] In the 2019-2020 school year, New Hampshire local public school districts reported average operating expenses of $16,823.88 per pupil, with added costs of tuition, transportation, facility purchase or construction, capital costs, and interest bringing the total average per student cost to $19,788.15.[xx]

Adequate Education Aid also includes Stabilization Aid, which was established as a method of offsetting the negative impacts on some communities of a significant revision of the per pupil education formula that took effect in SFY 2012.[xxi] For SFY 2021, the current State Budget expanded Adequate Education Aid to include additional resources, allocated on a per pupil basis but based on community factors. This assistance, which was estimated to add about $62.5 million in Adequate Education Aid when it was enacted, came in two forms. The majority of the additional aid came in the form of grants targeted at communities with smaller amounts of taxable property wealth per student, with a sliding scale increasing aid up to $1,750 per student as the equalized valuation per pupil declined. The remaining aid was allocated based on the concentration of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals in a community, which is determined based on family income being below or near poverty levels, or enrollment in certain programs, such as the Food Stamp Program. Communities with a higher percentage of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals receive additional aid per student, with a sliding scale of up to $350 per pupil added for eligible students in these communities.[xxii]

The Governor’s budget proposal would continue Stabilization Aid at current levels, but does not extend the targeted aid for communities with higher concentrations of students from low-income families or with less taxable property wealth per student. The budget proposal also appears to project lower total student enrollment, reducing the number of per pupil grants, but also projects higher student enrollment at public charter schools. Overall public school student enrollment in New Hampshire peaked in the 2002-2003 school year and has been declining in each subsequent year, with a more pronounced decline in enrolled students and an increase in home educated students during the pandemic.[xxiii] In aggregate, the Governor’s budget would reduce funding in the Adequate Education Aid line by $100.7 million (5.1 percent) in SFYs 2022-2023 relative to the amount appropriated for SFYs 2020-2021 in the current State Budget.

Public charter school aid would increase by $9.7 million (11.2 percent) in the two years of expenditures proposed by the Governor’s budget relative to the amount allocated in the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget as enacted.

Special education aid outside of the Adequate Education Grants, which provide assistance to schools for students with special education assistance needs totaling more than 350 percent of the estimated average state expenditure per pupil, would be funded at the same levels in the Governor’s proposal as in the current State Budget. The Department of Education reported this funding level, $30.8 million per year, met 94.5 percent of obligations in SFY 2020 and 100 percent in SFY 2021.[xxiv]

Tuition and transportation aid to school districts would also remain level in the Governor’s budget proposal, at $9 million per year. This assistance is designed to support enrollment for out-of-district students attending career and technical education programs at other schools.[xxv]

Free and Reduced-Price School Meal Enrollment Metric

Greater flexibility in federal free and reduced-price school meal programs, which was granted during the pandemic, broadened eligibility and allowed school districts to provide meals to students, often in their homes, without the previously required processes for verifying family income eligibility. As a result, the official counts for free and reduced-price school meal eligibility, which is used to distribute more aid to communities with more children from families with low incomes, dropped significantly even as household incomes from work also dropped in New Hampshire.[xxvi] Between the 2019-2020 school year and the 2020-2021 school year, State-identified free and reduced-price school enrollment eligibility dropped by 11,058 students (24.2 percent).[xxvii] The Governor proposes permitting, for SFY 2022, school districts and municipalities to use the percentage of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals in the 2019-2020 school year as a basis for aid in SFY 2022 if that percentage is higher. If a State of Emergency related to COVID-19 is still in effect for SFY 2023, or if federal waivers continue to provide aid without previously-required paperwork, school districts would be able to use the highest percentage of the school years including and since 2019-2020 as a basis for calculating State aid.

Public School Building and Infrastructure Aid

The Governor’s proposed budget includes a reduction in school building aid in the traditional school building aid formula, which provides State matching funds to support eligible school building projects. The New Hampshire Department of Education identified approximately $104.2 million in school building aid applications for SFYs 2022 and 2023. The Governor’s budget proposal would reduce aid in the SFYs 2022-2023 biennium by about $17.1 million (24.7 percent) to $51.9 million, compared to the $69.0 million allocated during the current biennium. The total appropriated in the current State Budget permitted funding for three new projects, as well as paying for ongoing debt service commitments; the Governor’s budget appears to continue paying debt service, but also appears to not incorporate any new school building projects.[xxviii]

However, the Governor’s proposed budget would appropriate $15.0 million each year, for a total of $30.0 million during the biennium, to the Public School Infrastructure Fund. Created in 2017 as a result of an amended infrastructure fund proposal in the budget recommended by the Governor that year, the aid provided to local school districts by the Public School Infrastructure Fund is directed by the Governor, in consultation with the Public School Infrastructure Commission, which is comprised of elected and appointed public officials. The Fund’s resources are deployed for certain types of projects, including safety upgrades, fire code compliance changes, fiber optic connections, compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and emergency readiness. Most of these projects have been relatively small projects, compared to the school building aid requests, that were designed to improve the security of school buildings.[xxix] The Governor proposes explicitly expanding the scope of projects funded by the Public School Infrastructure Fund to include energy efficient school buses.

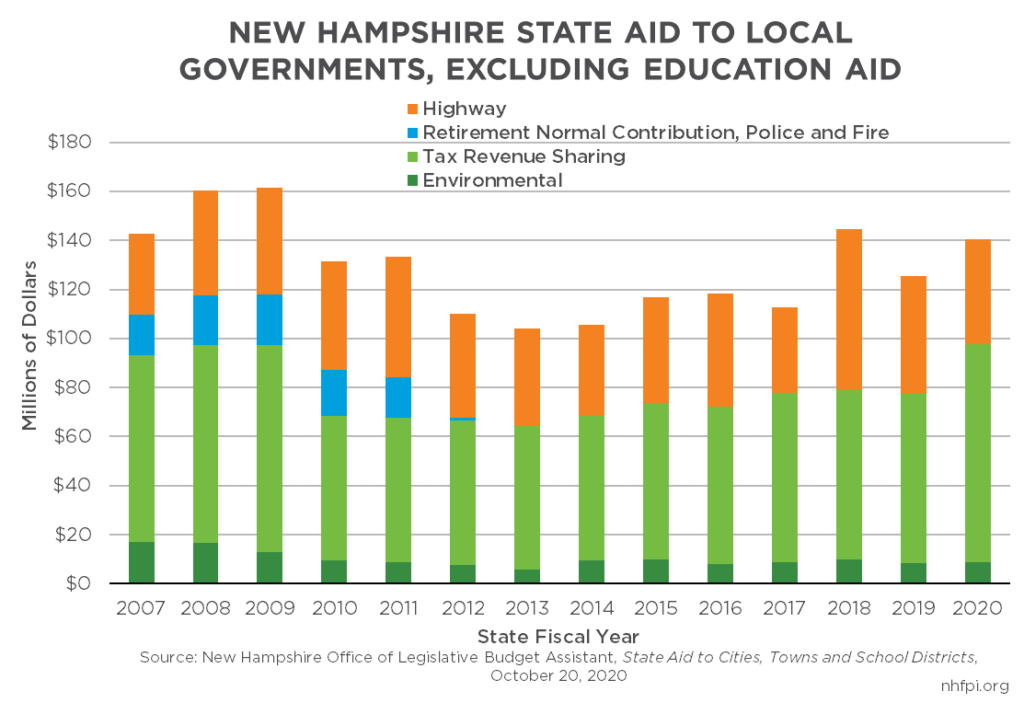

Non-Education Aid to Local Governments

Aid for local public education is the most significant transfer of resources from the State to local governments, but other assistance to municipalities and counties has a significant role in local budgets. Local property taxes account for more than half of all local government revenue in New Hampshire, while State grants constitute about a quarter of all revenue, and federal funding has a much smaller role. The total statewide tax commitment for local property taxes in Tax Year 2020 was about $3.7 billion; the State’s single largest tax revenue source, the Business Profits Tax, only collected about one-eighth of that amount of revenue in SFY 2020.[xxx] State aid to local governments that is not related to education includes aid for highway and bridge construction and highway block grants; environmental aid associated with water systems, pollution and flood control, and landfill closures; and general revenue sharing from Railroad Tax and Meals and Rentals Tax revenues. State aid to local governments for education totaled $1,048.3 million in SFY 2020, while non-education aid totaled about $140.5 million.[xxxi]

The Governor’s budget proposal would increase revenue sharing with municipalities through the Meals and Rentals Tax. The Meals and Rentals Tax is set to distribute 40 percent of collected revenue to municipalities on a per capita basis, but intervening statutes have suspended that provision. As a result, the Legislature established a catch-up formula to gradually increase the amount of revenue shared through the Meals and Rentals Tax by up to $5 million each year. However, that formula has also been suspended for all but two years between SFY 2011 and SFY 2021. In SFY 2019, the $68.8 million distribution to municipalities from the Meals and Rentals Tax was the equivalent of approximately 19.7 percent of the revenue collected by the tax.[xxxii]

The Governor proposed allowing the catch-up formula to function over the next two years, permitting a potential $5 million per year increase in aid to cities and towns for a total of up to $15 million in aid. The Governor’s proposal appropriates an increase of $5 million per year in the relevant budget line. However, the amount distributed depends on year-over-year increase in revenue collected through the Meals and Rentals Tax, which has been the major tax revenue source most directly negatively impacted by the pandemic.[xxxiii]

The current State Budget granted municipalities a total of $40 million in unrestricted revenue in addition to the existing Meals and Rentals Tax distribution. While aid through the Meals and Rentals Tax distribution would likely be increased, these annual revenue distributions of $20 million per year in the current State Budget would not continue under the Governor’s budget proposal. Revenue sharing based on the formula used in the first decade of this century would also be suspended, as it has been in State Budgets for the last ten years.

Under the Governor’s proposal, the State would also increase the amount expected to be paid by county governments for long-term supports and services delivered via Medicaid for adult county residents. The State and county governments split these costs for nursing home and community-based services for residents, with the federal government matching the combined contributions of the county governments and the State government. The Governor’s budget projects an overall increase in the cost of these services, but reduced the State’s contribution by $20.8 million (67.5 percent) in the two years relative to the amount budgeted in the SFYs 2020-2021 State Budget as enacted. These two changes, and proposed statutory increases in caps on county payments in the Governor’s budget proposal, would increase expected payments from the ten counties by $47.5 million (19.8 percent) in aggregate, adding significant upward pressure on county property taxes.[xxxiv]

The Governor’s budget proposal would also continue a suspension of certain environmental infrastructure grants to local governments and the general revenue sharing program with cities and towns.

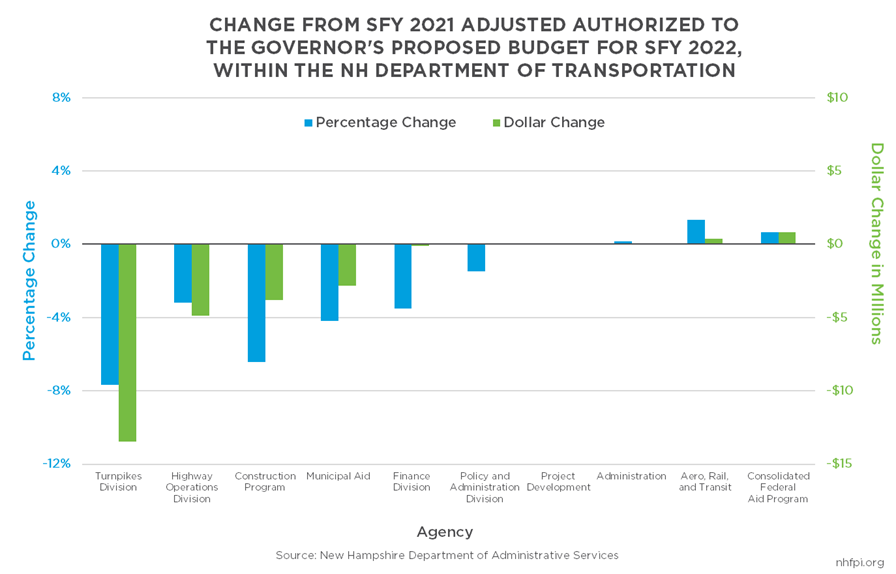

Transportation

The impacts of the pandemic have been significant for highway funding, as reduced traffic volume has resulted in lower revenues. Although General Fund and Education Trust Fund revenue sources are projected to recover relatively quickly, revenues associated with the Highway Fund and the Turnpike Fund, particularly tax revenues from motor fuel purchases and turnpike tolling, are expected to recover more slowly. As a result, activities supported by the Highway Fund and the Turnpike Fund would be budgeted less under the Governor’s proposal.

Funding for Turnpike construction and repair materials would drop from about $24 million per year to $17 million annually. Funding for toll collection operations would increase, including costs for both technology hardware and software and contracts for services. Funding for equipment replacement would also be boosted for the Bureau of Turnpikes.

Budgeted aid for municipal governments from the Highway Fund would decline under the Governor’s budget proposal. Certain construction material costs and operations related to highways would also be appropriated fewer funds than previously authorized.

The Governor’s budget proposal would also enable remaining funds from a $20 million appropriation to address structurally deficient bridges, originally made in 2018 from General Fund surplus, to lapse to the Highway Fund at the end of SFY 2021. Lapsing this revenue to the Highway Fund would enable these dollars to be used for other road and highway-related costs.

Other Initiatives

The budget presented by the Governor includes both proposed funding and policy changes, including many significant new initiatives that interact with many areas of State operations and services.

Student Debt Assistance

The Governor’s budget proposal would alter the New Hampshire Excellence in Higher Education Endowment Trust Fund, which collects revenue from two 529 College Tuition Savings Plans sponsored by the State of New Hampshire, to expand from supporting scholarships for students to also helping to alleviate the education debt of former students.[xxxv] The Governor would direct the majority of the disbursements from the renamed New Hampshire Excellence in Higher Education Trust Fund to the Workforce Development Student Debt Relief Program. This program would provide debt relief for a person working full time in New Hampshire, with a degree from a regionally-accredited institution, who is not participating in any other student debt forgiveness program, and is working in biotechnology, in a licensed medical profession, in an industry determined to be eligible though periodic evaluation by the Department of Business and Economic Affairs, or as a nurse at New Hampshire Hospital, the State’s Glencliff nursing home, or the State’s veterans’ home.

The Department of Education would also be permitted to accept gifts and contributions from individuals or organizations to the New Hampshire Scholar’s Program, which would not receive General Fund support in the Governor’s budget proposal.

Rainy Day Fund Limit

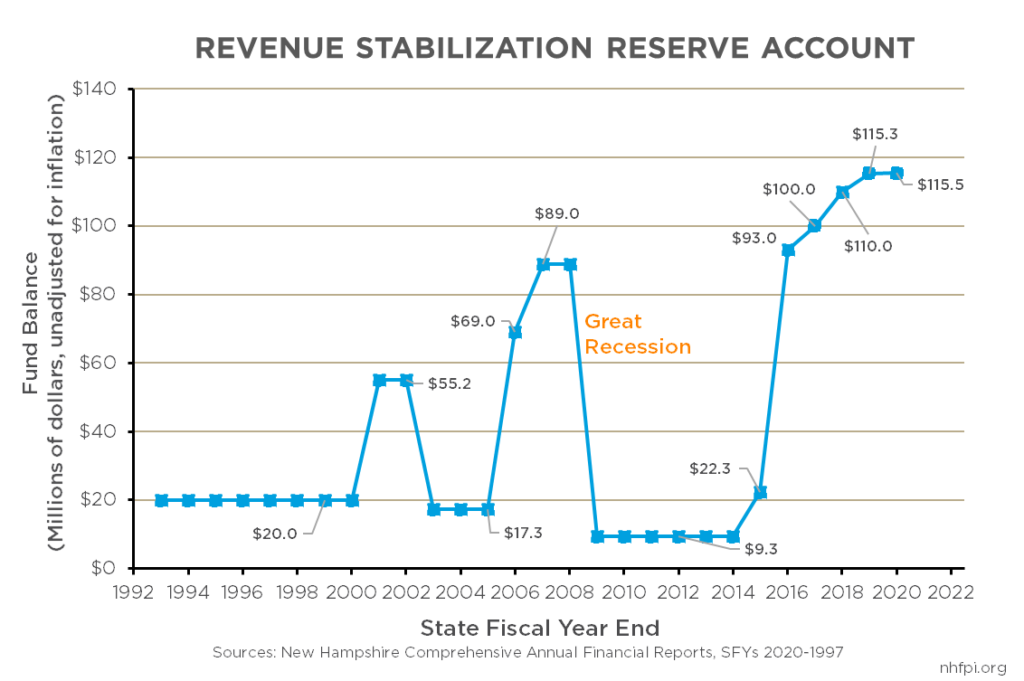

The Revenue Stabilization Reserve Account, also known as the Rainy Day Fund, is designed in statute to fill a State Budget’s revenue shortfall at the end of a budget biennium. The amount than can be stored in the Rainy Day Fund from previous revenue surpluses is capped at 10 percent of the General Fund revenue collected in the previous year, and any additional surplus above that cap would lapse to the General Fund. State revenues collected as part of large legal settlements, of which 10 percent go to the Rainy Day Fund, are not subject to the cap. The Rainy Day Fund held $115.5 million at the end of SFY 2020, which was $46.7 million below its cap, based on SFY 2019 revenues; the cap based on SFY 2020 revenues would be lower, but still about $37.0 million above the Rainy Day Fund’s most recently audited total.[xxxvi] The Governor has proposed basing the cap on the total revenues to the General Fund from the most recently completed biennium, which would significantly increase the cap relative to current policy, barring dramatic changes in revenue on a year-over-year basis.

Other Provisions

The Governor’s budget proposal includes a wide variety of additional policy changes and shifts in funding, including:

- establishing a body-worn and dashboard camera fund to provide matching dollars for local law enforcement agencies purchasing camera equipment, and providing $1.0 million in funding for SFY 2022

- creating a commission to craft proposed legislation for an independent statewide entity to receive complaints regarding sworn and elected law enforcement officers, with a $517,250 appropriation for the commission

- appropriating $1.0 million during the biennium to the FRM Victims’ Contribution Recovery Fund

- reducing the number of Adult Parole Board members from nine to five, and add qualification requirements in statute for the four members who are not the gubernatorially-appointed chair

- suspending certain aid payments to hospitals with an amendment to the State Medicaid plan

- requiring any revenue that results due to an increased federal match in a DHHS program beyond the amount expected in the State Budget to lapse to the General Fund

- adjusting the membership of the Hearing Care Provider Governing Board, and changing statutes governing hearing care professionals

- allocating more than $2.0 million to specific projects in two State Parks, an historic site, and a State campground

- extending funding availability for studying, investigating, testing, and designing preliminary treatment for perfluorinated chemicals in water

- altering laws directing reimbursements for property damage inflicted by bears on agricultural operations

- limiting the ability of the Public Utilities Commission to implement an energy efficiency resource standard

- exempting the Department of Administrative Services from complying with the recommendations of certain performance audits conducted by legislative staff and requirements in existing Executive Orders regarding energy efficiency and monitoring of energy use, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions

- maintaining expanded powers for the Department of Administrative Services to consolidate human resources, payroll, and business processing positions and functions across the State’s departments

- authorizing the sale of State property formerly known as the Laconia State School

- establishing a Director of Intergovernmental Affairs in the Department of Business and Economic Affairs

- limiting the powers and responsibilities of the State Apprenticeship Advisory Council and certain minimum standards for apprenticeship agreements

- suspending the distribution of 3.15 percent of Meals and Rentals Tax revenues to the Division of Travel and Tourism Development during the biennium

- permitting the Business Finance Authority to support biotechnology manufacturing or industrial projects and setting the maximum bond guarantee authority thresholds for the Business Finance Authority related to this purpose to $100 million, but with no guarantees offered after 2023

Revenue Projections and Tax Policy Changes

As part of the proposed State Budget, the Governor provided both revenue projections and suggested changes to tax policy for the upcoming biennium. The tax policy changes include both changes to take effect during the budget biennium and some changes beyond the end of the next biennium, substantially affecting State revenues beyond June 2023 when the next State Budget will end.

Governor and House Revenue Projections

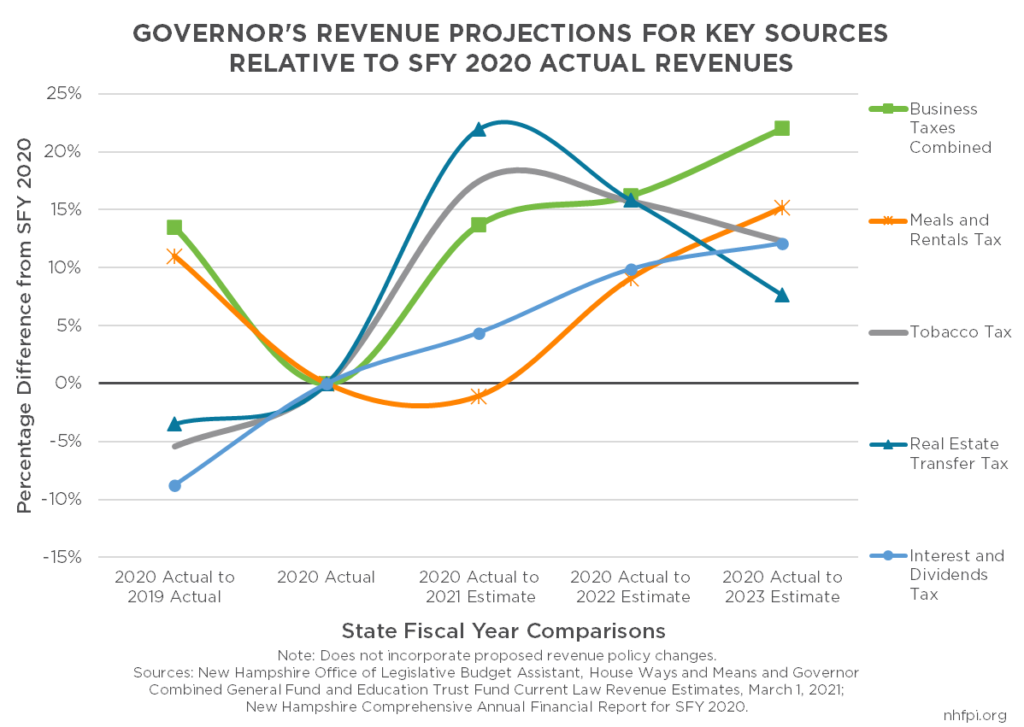

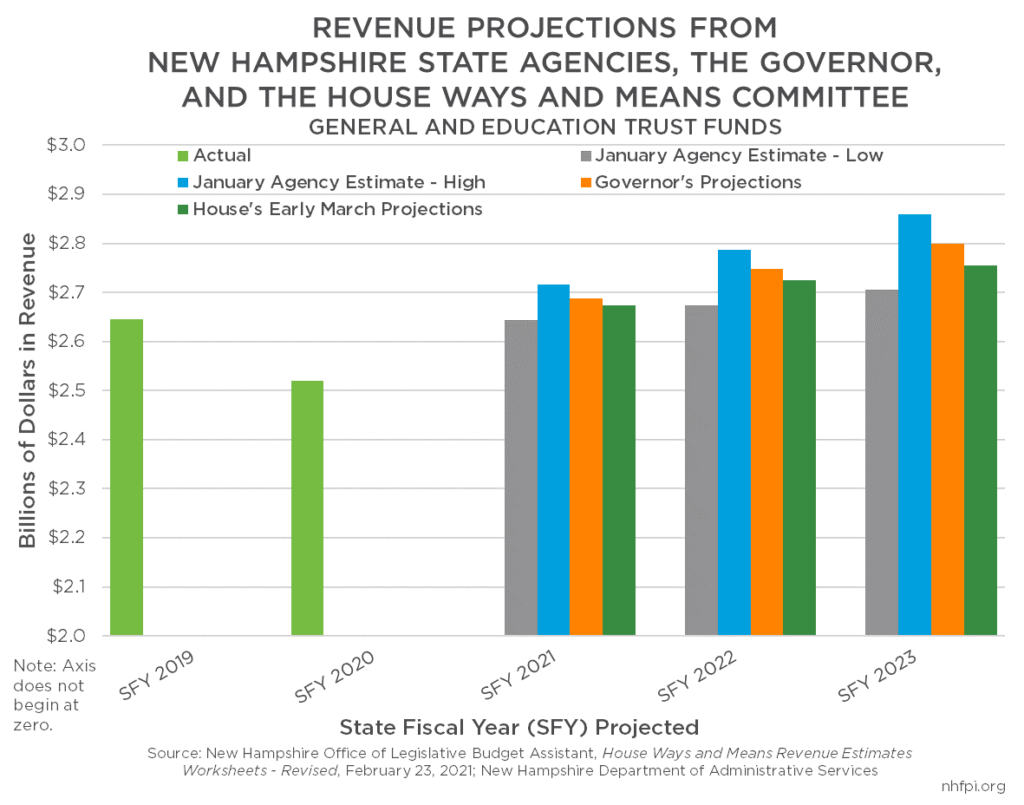

The Governor proposed revenue projections that fell between the range of estimates provided by State agencies in January 2021. Both the State agencies and the Governor projected a revenue recovery for the remainder of SFY 2021, and increases in General and Education Trust Funds revenue in each of SFYs 2022 and 2023, suggesting a clear and sustained economic recovery. The Governor projected key individual taxes within the range of revenues projected by the Department of Revenue Administration for those revenue sources, but was close to the optimistic ends of those revenue estimate ranges for the Meals and Rentals Tax and the Real Estate Transfer Tax.

The Governor’s projections anticipate a robust Meals and Rentals Tax revenue recovery during the budget biennium after a decline in SFY 2021. The Governor also anticipates the Real Estate Transfer Tax will continue to be supported by a robust housing market, as single-family home sales are a critical part of the tax base and have been very strong thus far in SFY 2021 despite a lack of inventory and a severe lack of housing overall in New Hampshire. This lack of inventory would eventually contribute to fewer home sales, however, in the Governor’s projections. The Governor also appears to anticipate sustained higher Tobacco Tax sales in SFY 2021, which have been boosted by a policy change in Massachusetts limiting certain taxable retail sales and likely bringing more customers to New Hampshire, as well as pandemic-related impacts such as stocking cigarettes for longer periods and added stress on individuals.[xxxvii] However, Tobacco Tax revenues would then return to a long-term decline in the Governor’s projections.[xxxviii]

The House Ways and Means Committee also produced revenue estimates for the budget biennium, and those estimates are less optimistic than the Governor’s projections. Across SFYs 2021, 2022, and 2023, those estimates project about $79.6 million less for the General and Education Trust Funds than anticipated by the Governor. The House Ways and Means Committee was less optimistic than the Governor relative to receipts from the two primary business taxes in SFY 2023, as well as Meals and Rentals Tax revenues throughout all three years projected.[xxxix]

Tax Policy Changes

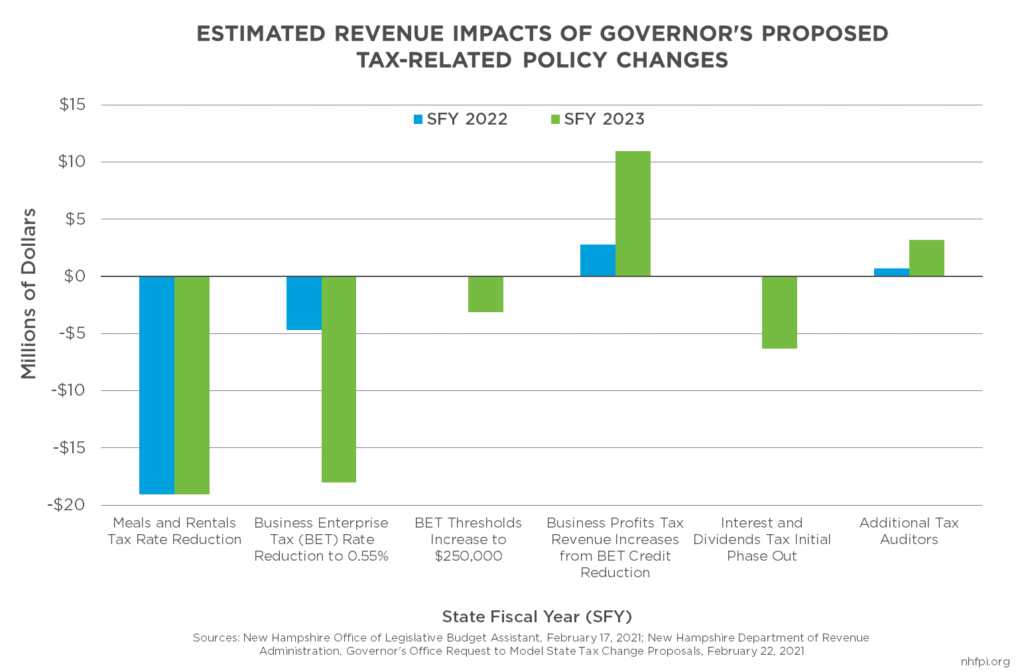

The Governor also proposed tax policy changes as part of the budget proposal. In aggregate, these policy changes would result in an estimated $52.5 million less revenue to the General and Education Trust Funds during the biennium, although official estimates of the revenue impact have varied since the Governor’s proposals were first announced.[xl]

The tax change with the largest negative revenue impact during the budget biennium proposed by the Governor is a reduction in the Meals and Rentals Tax rate. Restaurant meals are about 80 percent of the tax base for the Meals and Rentals Tax, and the balance is comprised of hotel room and car rentals.[xli] The Governor proposed reducing this tax rate from 9.0 percent to 8.5 percent. This change would reduce the tax paid by the customer on a $24 restaurant meal purchase by 12 cents. The Department of Revenue Administration estimates the rate change would reduce revenues to the General and Education Trust Funds by slightly more than $19.0 million each year.

The Governor’s budget also proposes reducing the rate of, and eventually eliminating, the Interest and Dividends Tax over a five-year period. The Interest and Dividends Tax base is income generated by asset ownership, such as dividends or distributions from stock ownership or interest from bank accounts. In tax year 2018, the most recent year with available data, there were 66,284 filers, 98.4 percent of whom were individuals or joint filers rather than estates or business entities. High-income filers were a significant part of the Interest and Dividends Tax base, as 49.0 percent of the tax revenue paid came from the top 2.4 percent of filers; these filers each reported at least $200,000 in taxable interest, dividend, and distribution income (not including wages, salaries, capital gains, or other income not taxed under this law).[xlii] Starting in 2023, the Interest and Dividends Tax rate would drop by one percentage point each year, reducing revenue during the budget biennium by an estimated $6.3 million. This tax revenue source generated $125.7 million for the General Fund in SFY 2020, or 8.2 percent of all General Fund revenue collected that year; a repeal of the tax would lead to significant revenue losses relative to current policy.

The Governor also proposed reducing the Business Enterprise Tax (BET) rate from 0.60 percent to 0.55 percent. The BET is based on compensation and interest paid or accrued and dividends paid, and a business entity does not need to be making a profit to have a BET liability; this is notably different from the State’s other primary business tax, the Business Profits Tax (BPT). While the BET has a broader base than the BPT, the tax still draws significantly from larger business entities; 0.81 percent of filing businesses in Tax Year 2018 paid 53.0 percent of the tax revenue collected in that year. Reducing the BET would lead to limited revenue losses in the first year of the biennium, due to tax rate timing changes, but those revenue losses would increase to $22.7 million over the course of the biennium.

The Governor also proposes increasing both existing BET filing thresholds to $250,000, which would make the smallest entities less likely to need to file. The two thresholds are based on separate components of business activity. The current threshold for the BET’s actual tax base, comprised of compensation, interest, and dividends paid, is currently $111,000. Businesses have a separate filing threshold based on gross receipts, which is currently $222,000. The Governor proposes raising both, which the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration estimates would cost the General and Education Trust Funds approximately $3.1 million during the biennium, primarily in SFY 2023.[xliii]

As the BET can be deployed as a dollar-for-dollar credit against the BPT, reducing the BET liability for businesses that do have a BPT liability means those businesses will owe more in BPT. As a result, BPT revenues would increase, but not sufficiently to offset the loss in BET, as only businesses that have a profit would see their liabilities under the BPT increase.

Also affecting revenue during the biennium, the Governor’s budget would add tax auditors to the Department of Revenue Administration, which would add an anticipated $3.9 million in General and Education Trust Funds during the biennium. Additionally, the Governor proposed limiting the amount of credit against BPT and BET liabilities that businesses could hold with the State to 50 percent of total tax liability by entity, which reduces the likelihood businesses would use enough credits held with the State to generate a significant revenue shortfall.

Outside of General and Education Trust Funds revenues, the Governor proposed changes to the thresholds for automatically-assessed payroll taxes that support the Unemployment Compensation Fund, which supports unemployment benefits and taxes employers at different rates based on the balance level of the Unemployment Compensation Fund. The Governor also proposed eliminating the provisional emergency authority of New Hampshire Employment Security to enable certain surcharges.[xliv]

Conclusion

The next State Budget will fund public services during a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The Governor’s budget proposal provides a potential framework, and the Legislature, informed by subsequently available information, will build on the framework in the coming months. With the trajectory of the public health and economic recovery subject to considerable uncertainty, the next State Budget will need to be sufficiently resourced to meet the needs of the State’s residents in a dynamic environment. Granite Staters who entered this crisis as the most vulnerable to both health and financial hardships, and with the least resources to weather it, have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Given the recovery from the Great Recession of 2007-2009 was slow during much of its duration in New Hampshire, and that wages did not rise equitably during the course of that recovery, there is significant risk low-income individuals, families, and communities will fall even further behind the conditions indicated by the topline economic numbers.

The Governor’s budget proposal includes funding for certain key supports, such as bolstering mental health services at New Hampshire Hospital, harnessing federal funds to treat substance use disorders, and helping to ensure federal changes to expand food assistance programs for students do not result in less funding for their school districts. However, the discontinuation of education aid targeted at communities with smaller relative property tax bases and more students from families with low incomes, at a time when those communities are likely in greater need than when the one-time aid was announced in 2019, may offset the benefits from federal and other supports.

Public policy can help build an inclusive, equitable, and sustainable economic recovery. Assistance to individuals and families with low incomes can both permit those households to make ends meet and effectively boost economic growth. Both direct services from the State government and assistance to local communities and organizations providing these services can help support this recovery and help ensure it reaches all Granite Staters. The next State Budget will need to wisely and purposely deploy sufficient resources to successfully help foster an equitable and inclusive economy for all New Hampshire residents during a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Endnotes

[i] The analysis in this Issue Brief is based primarily on the Governor’s proposed operating budget bill, released February 11, 2021, the Governor’s Executive Budget Summary, also released February 11, 2021, and House Bill 2, introduced March 2, 2021. For relevant background on the economy and likely needs during the upcoming budget biennium, see NHFPI’s February 2021 Issue Brief Designing a State Budget to Meet New Hampshire’s Needs During and After the COVID-19 Crisis.

[ii] This comparable amount does not include the appropriations allocated in the current State Budget’s Trailer Bill (Chapter 346, Laws of 2019). These Trailer Bill appropriations totaled more than $150 million in General Fund appropriations. For details, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s Comparative Statement of Undesignated Surplus from September 25, 2019.

[iii] For more information on this federal statute and grants to states, see the website of the U.S. Department of Justice Office for Victims of Crime.

[iv] For more information on the Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief program, see NHFPI’s June 17, 2019 post Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief Applications Due June 30.

[v] For more information on this revenue source and its purpose, see the NH DWG Trust Fund website.

[vi] See the Department of Safety’s February 22, 2021 presentation to the House Finance Committee, Division II.

[vii] For examinations of the Governor’s 2017 and 2019 State Budget proposals, see NHFPI’s February 2017 Issue Brief Governor Sununu’s Proposed Budget and March 2019 Issue Brief The Governor’s Budget Proposal, State Fiscal Years 2020-2021.

[viii] For more information, see the University System of New Hampshire – Our Institutions.

[ix] See information on each of the colleges and academic centers at the Community College System of New Hampshire – Colleges and Programs.

[x] Medicaid enrollment data from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography, January 2021. For the cost of Medicaid, see NHFPI’s December 7, 2020 presentation The COVID-19 Crisis and State Budget Implications for New Hampshire.

[xi] For information and research related to the importance of child care in the economy and the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, see the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Community Development Research Brief, Child Care, COVID-19, and Our Economic Future, September 2020.

[xii] For more information regarding housing constraints prior to and during the pandemic, see NHFPI’s September 2020 Issue Brief New and Expanded Challenges Facing Vulnerable Populations in New Hampshire, NHFPI’s January 25, 2021 presentation Economic Security and the Safety Net, and the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority’s November/December Housing Market Snapshot.

[xiii] For more information on Medicaid managed care organizations, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

[xiv] For more information on expanded Medicaid, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes and NHFPI’s May 10, 2018 post Senate Approves Medicaid Expansion Bill as Amended by the House.

[xv] The Office of Professional Licensure and Certification has information regarding the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program on its website, and more information can be found at New Hampshire PDMP.

[xvi] See RSA 161-F:40.

[xvii] For more information, see the September 1, 2020 Informational Item from the DHHS provided to the Governor and Executive Council.

[xviii] Read the Commission to Study School Funding’s December 2020 report on the Commission’s website, hosted by the University of New Hampshire.

[xix] For more information on Adequate Education Grants, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2021 Fiscal Issue Brief: Calculating Education Grants, as well as the New Hampshire Department of Education’s November 2020 explainer FY2022 Adequate Education Aid: How the Cost of an Opportunity for an Adequate Education is Determined and NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[xx] For more information, see NHFPI’s February 2021 presentation The New Hampshire State Budget and Education Funding.

[xxi] To learn more about Stabilization Aid, see NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Education Funding in the House Budget.

[xxii] For more information on the education funding provisions in the current State Budget, see NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxiii] For historical enrollment, see NHFPI’s December 2019 presentation Demographics, Age Groups, and Incomes in New Hampshire. To see discussions of historical enrollment figures used in the State Budget proposal projections and projections for public charter schools, see the Department of Education’s Division II – House Finance, State Adequacy Aid Documents, March 3, 2021.

[xxiv] For more information, see the Department of Education’s March 3, 2021 Special Education Aid Summary.

[xxv] Learn more about Tuition and Transportation Aid in the Department of Education’s March 3, 2021 Tuition & Transportation Reimbursement Summary.

[xxvi] For more information on impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on family incomes in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s January 20, 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s Economy, Household Finances, and State Revenues and NHFPI’s September 2020 Issue Brief Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xxvii] See the New Hampshire Department of Education’s Division II – House Finance, State Adequacy Aid Documents, March 3, 2021, page 35 for free and reduced-price school enrollment changes data.

[xxviii] For more information and the list of school building aid applicants for the upcoming State Budget biennium, see the Department of Education’s March 3, 2021 School Building Aid Summary.

[xxix] For more information on these expenditures, see the Department of Education’s March 3, 2021 Public School Infrastructure Fund Summary.

[xxx] For more information, see NHFPI’s February 25, 2021 presentation How Public Services are Funded in New Hampshire.

[xxxi] For a complete chronicling of local government assistance, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s State Aid to Cities, Towns and School Districts, Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2020.

[xxxii] For more information on the Meals and Rentals Tax and local aid, see the New Hampshire Municipal Association’s February 25, 2021 presentation How Public Services are Funded in New Hampshire, RSA 78-A:26, and New Hampshire’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020.

[xxxiii] See the New Hampshire Municipal Association’s February 25, 2021 presentation How Public Services are Funded in New Hampshire and RSA 78-A:26.

[xxxiv] For more information, see NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021 and NHFPI’s August 2019 Fact Sheet County Medicaid Funding Obligations for Long-Term Care.

[xxxv] To learn more about the existing program, see the State Treasury Higher Education Division’s May 2, 2018 presentation UNIQUE Scholarship Programs.

[xxxvi] To read more about the Rainy Day Fund, see NHFPI’s December 21, 2020 presentation Budget Shortfall Update, The General Fund, and The Rainy Day Fund and its sources.

[xxxvii] For more information on Tobacco Tax receipts, see NHFPI’s November 30, 2020 post Updated Revenue Projections Suggest Much Smaller Budget Shortfall.

[xxxviii] Information regarding the historical long-term decline in Tobacco Tax revenues is available in NHFPI’s May 2017 publication Revenue in Review.

[xxxix] For summaries of State revenue projections from both the Governor and the House Ways and Means Committees, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant, House Ways and Means Revenue Estimates Worksheets – Revised, February 23, 2021 and House Ways and Means and Governor Combined General Fund and Education Trust Fund Current Law Revenue Estimates, March 1, 2021.

[xl] The Governor’s office provided initial estimates, followed by a subsequent and more detailed narrative from the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration, which included some slightly different estimates. Estimates confirmed by the Department of Revenue Administration prior to the release of House Bill 2 are used in this Issue Brief.

[xli] See the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s presentation to the Legislature’s biennial Joint Economic Briefing on January 19, 2021.

[xlii] For more information, see NHFPI’s February 19, 2021 webinar Examining the State Budget: The Governor’s Proposal and the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s 2020 Annual Report, page 53.

[xliii] See the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s narrative regarding the Governor’s proposed tax policy changes, presented to the House Ways and Means Committee on February 22, 2021.