Funding for New Hampshire’s State Budget relies on revenues generated from economic activity, which has been severely curtailed by the COVID-19 crisis. These State revenues pay for key services for Granite Staters, including supports and assistance designed to help those facing financial hardship. With nearly half of New Hampshire households reporting a loss in employment income since mid-March, the need for State services intended to aid families with low incomes, as well as support for education and health services, has increased during the pandemic and will likely remain elevated into the next State Budget biennium.[i]

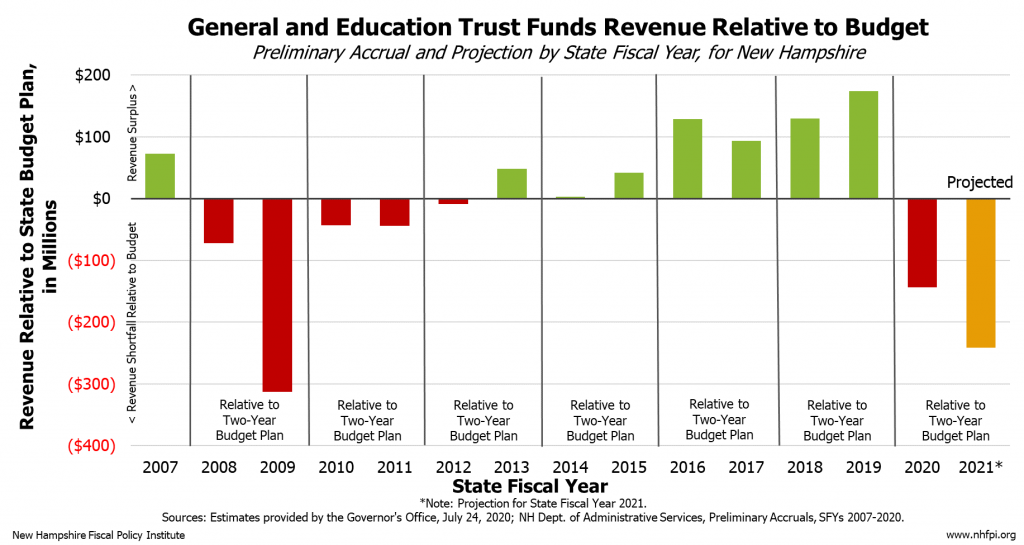

The economic shock of the COVID-19 crisis has led to significant State revenue declines, including a 5.5 percent budget shortfall in two key funds through the 12 months ending in June, the first half of the State’s two-year budget. The projected shortfall for these funds during the second year of the State Budget is 9.1 percent. Tax revenues have been swiftly impacted by the crisis, including revenues stemming from business profits, business compensation, gasoline sales, and restaurant meal purchases, and hotel and car rentals. While revenues were already declining after certain one-time revenues collected in the previous two years disappeared, this decline poses significant risk to the services funded by the State Budget, many of which are especially critical given the income losses and increased need for health services created by the pandemic.[ii] Although they differ in some key ways and significant uncertainty remains, the State revenue impacts may be similar in magnitude to those seen during the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, which preceded policy decisions that dramatically reduced funding for key State agencies.[iii]

In both the Great Recession and the 2001 recession, the federal government provided assistance to State governments to help offset revenue losses and preserve or bolster State-funded services. Although the federal government deployed significant resources at the outset of the COVID-19 crisis, including aid that could be directed by states with a high degree of flexibility, assistance that can be used to offset budget shortfalls has been very limited relative to the magnitude of the declines in revenue. Additional assistance from the federal government, depending on its form, would help ensure key services for Granite Staters are sustained through this crisis.

This Issue Brief examines the initial shortfall in State revenues, analyzes official revenue shortfall projections, and summarizes potential forms of future federal assistance to the State that would help retain and support key services for New Hampshire’s residents.

Funding the State Budget

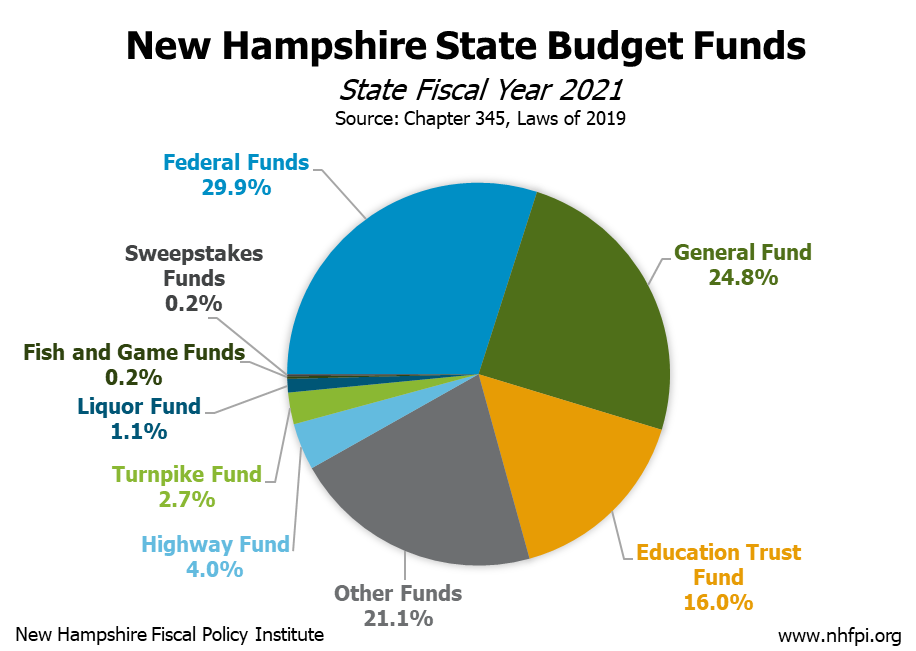

The General and Education Trust Funds, and the revenues that flow to those funds, are central to New Hampshire’s State Budget.[iv] The Education Trust Fund finances the education grants provided to local school districts on a per-student basis to support public education, and General Fund dollars are appropriated to pay for a wide variety of activities throughout State government.[v] These two funds accounted for approximately 41 percent of all State Budget appropriations for State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2021. The Funds are typically balanced together, with the General Fund filling any shortfall in the Education Trust Fund, and they share many revenue sources. Transfers and grants from the federal government to help fund key programs, such as Medicaid and highway construction, support about 30 percent of New Hampshire’s State Budget. The Highway Fund’s revenues comprised approximately four percent of all State Budget appropriations for SFY 2021, while the Turnpike Fund accounted for just under three percent.

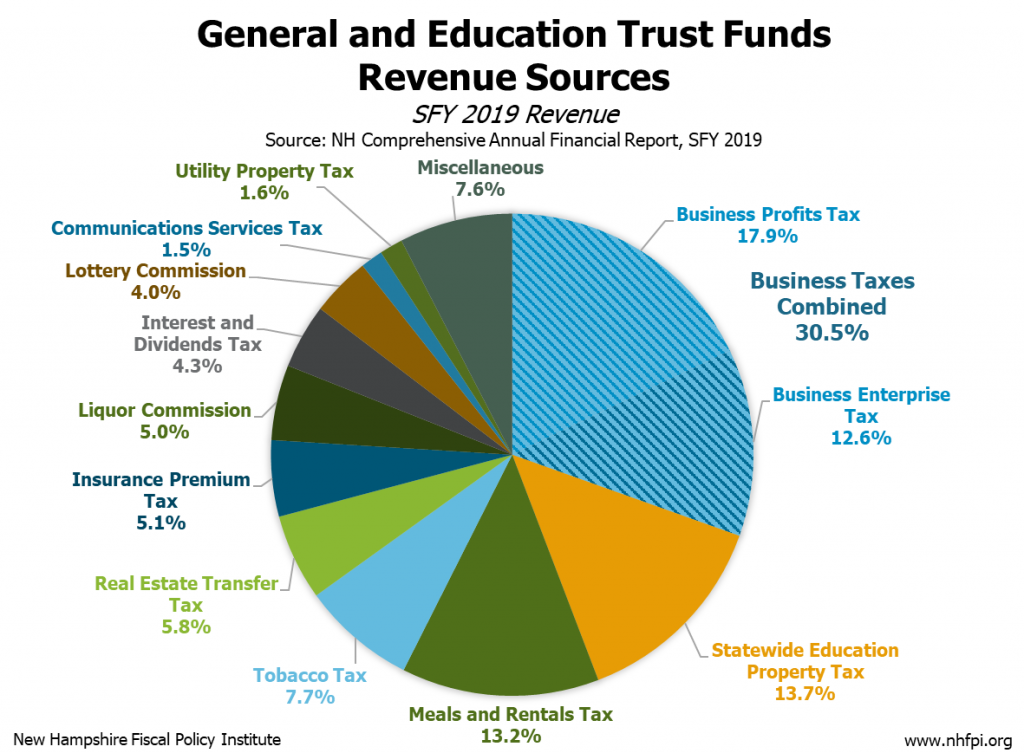

The General and Education Trust Funds are supported by a diverse set of revenue sources, including both tax revenues and revenue generated by the State’s Lottery and Liquor Commissions. The Statewide Education Property Tax is raised and retained locally, and is set to raise the same amount each year. The State’s two primary business taxes, the Business Profits Tax (BPT) and the Business Enterprise Tax (BET), are typically filed and analyzed together and accounted for about three in ten dollars collected to these two funds. The Meals and Rentals Tax is the second-largest single tax revenue source, after the BPT, that is collected by the State.[vi]

The Highway Fund is supported primarily by taxes on motor fuels, such as gasoline, and motor vehicle registration fees. Most revenue to the Turnpike Fund flows from tolls and related payments on certain limited access Turnpike system highways.

State Revenues During the COVID-19 Crisis

The most severe impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on New Hampshire’s State revenues did not appear until April, May, and June of calendar year 2020, which was the last quarter of SFY 2020. Despite the relative health of the economy in the first three quarters of the year, revenues overall were down so significantly by the end of SFY 2020 that General and Education Trust Fund revenues were $143.9 million (5.5 percent) below the State Revenue Plan for the year and $163.0 million (6.2 percent) below SFY 2019, based on unaudited preliminary figures. Cash revenues in February 2020 had been slightly above the State Revenue Plan, so the entire shortfall was generated in subsequent months.[vii] This shortfall came as revenues were already undergoing an expected decline relative to prior years.

Expected Declines in Business Tax Receipts

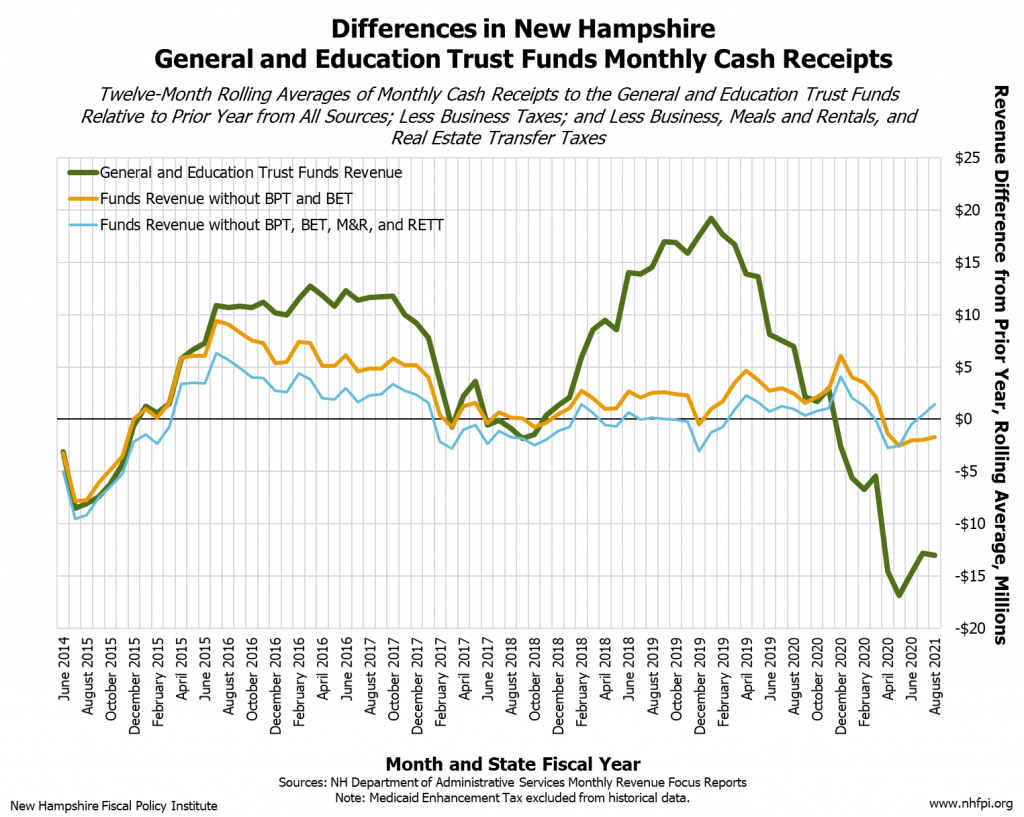

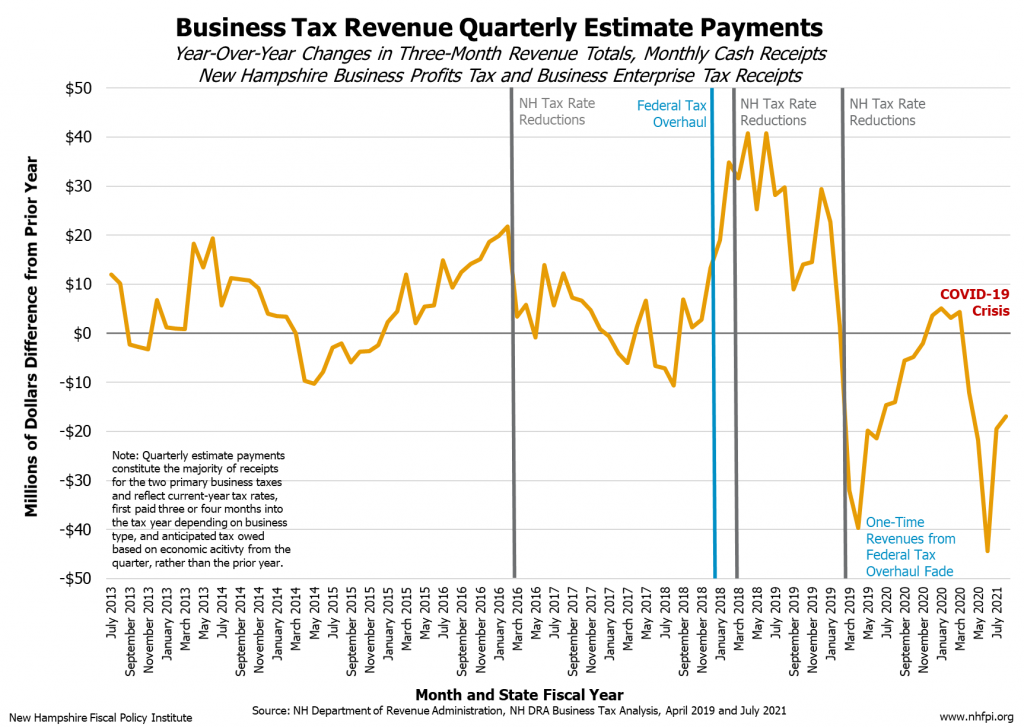

State revenues were declining relative to prior highs throughout much of SFY 2020 due to the disappearance of one-time effects from the federal tax overhaul on business tax receipts. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed by Congress and signed into law in December 2017, had a swift and immediate impact on New Hampshire’s BPT revenues. Federal corporate tax law changed to incentivize repatriation of multinational business revenue previously held overseas, which resulted in New Hampshire’s BPT collecting significant amounts of one-time revenue. The changes also may have spurred additional mergers and acquisitions, which can create one-time revenue impacts in the BPT. While there were other impacts, these factors appeared to cause a spike in business tax receipts starting in SFY 2018 and continuing into SFY 2019.[viii]

While business tax receipts were higher during this period, other tax revenues remained relatively steady, suggesting moderate economic growth. The underlying conditions that supported other State revenue streams did not appear to change significantly in aggregate during this time period. Relative to this recent spike in revenues, the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have been much more significant and widespread.

Swift Impact on Key Revenues

The necessary efforts to mitigate the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus have contributed to a rapid downturn in State revenues. These impacts have been most clearly evident in two of the State’s largest revenue streams, the combined BPT and BET receipts and the Meals and Rentals Tax, as well as motor fuel tax revenues. Other key revenue sources, such as Liquor and Lottery Commission sales, appear to have performed as expected in the State Revenue Plan, while receipts from the Tobacco Tax and the Interest and Dividends Tax have been notably higher than anticipated.

Business tax receipts were likely impacted by some of the global economic impacts of the crisis before the pandemic reached New Hampshire, as large, multinational firms typically pay a significant portion of the BPT in New Hampshire.[ix] However, the swift global onset of the pandemic renders the ability to distinguish impacts from distant geographies and those locally difficult.

Most business tax receipts come through quarterly estimate payments; these payments totaled 67 percent of business tax revenue in SFY 2018. About 90 percent of businesses have a tax year that coincides with the calendar year. The State requires that companies produce estimates of expected tax liabilities for their tax years. These estimates are due quarterly, except when filed with returns from the prior year. These payment requirements result in April, June, September, and December being particularly important months for business tax revenues in New Hampshire. April is also the month during which most calendar year businesses are required to file their final return or extension for the prior tax year; only partnerships are required to file in March.[x]

This year, the federal government delayed tax payments to July 15, while the State delayed payments from certain businesses to June 15.[xi] This change led to reduced payments in April and increased payments in June and July, as some business entities appeared to have paid in State taxes in line with the federal deadline.[xii] Total cash receipts from the two primary business taxes were $55.2 million (13.3 percent) lower in total from March to August than they were in the same months of the previous year. Quarterly estimate payments, which reflect current activity rather than activity from the prior year represented in tax returns and extensions, were down $38.7 million (16.7 percent) in the March to August period relative to the prior year.

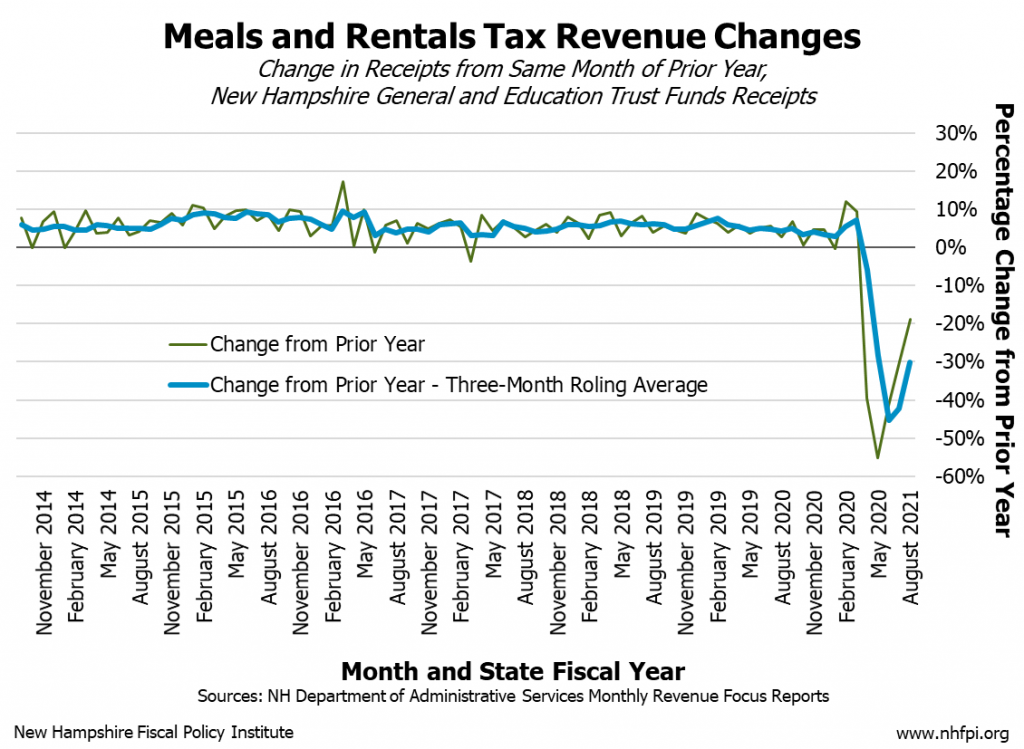

Meals and Rentals Tax revenues were even more swiftly and severely impacted. The temporary closure of dine-in spaces in restaurants and other efforts individuals, businesses, and governments took to avoid exacerbating the pandemic dramatically reduced activity taxable under the State’s second-largest collected tax revenue source. Despite the pandemic’s impacts being largely confined to the last four months of SFY 2020, Meals and Rentals Tax receipts were $54.7 million (14.8 percent) below planned amounts for all of SFY 2020, with May cash receipts (reflecting April activity) alone under the planned amounts by $15.3 million (58.0 percent). From April to August, Meals and Rentals Tax receipts, which reflect economic activity from the prior month, were $53.7 million (35.1 percent) lower than the same period in the previous year.

Revenues from the motor fuels tax, also known as the gasoline road toll, have fallen short of expectations for the year. Revenue from this source to the Highway Fund ended SFY 2020 at $10.1 million (7.9 percent) below Plan for the year. Reduced travel during April 2020 led to the State reporting an approximately 36 percent decline in fuel consumption relative to April 2019, and a nearly 25 percent decline in May 2020 relative to the prior year. July and August cash receipts from the motor fuels tax were $3.1 million (13.6 percent) below the State Revenue Plan.

Preliminary Shortfall Estimates for the First Half of the Budget

Estimates provided by State agencies in late July and preliminary accrual estimates showed significant revenue shortfalls in key funds at the end of SFY 2020, which marked the halfway point for the current State Budget biennium. Revenues for the General and Education Trust Funds combined were $143.9 million (5.5 percent) below the State Revenue Plan, while Highway Fund revenues were reported at $7.7 million (3.4 percent) below Plan.[xiii] Turnpike Fund revenues were approximately $13.3 million (9.7 percent) below Plan on a cash basis.[xiv] While the largest shortfalls were in the combined General and Education Trust Fund revenues, General Fund dollars have been transferred to support the Highway Fund in the last two biennial State Budgets.[xv] These funds may also interact in the next State Budget, depending on the revenue constraints and various service needs facing policymakers in early 2021. These policymakers will likely have to consider shortfalls generated during the first half of the current State Budget, as well as an expected and larger shortfall in SFY 2021, when crafting the SFYs 2022-2023 State Budget.

Projections for the Budget Shortfall

Forecasts for SFY 2021, the second half of the current biennial State Budget, include significant amounts of uncertainty. Key factors influencing the duration of the public health crisis and the speed of the economic recovery remain unknown, increasing the reliance of any set of projections on pivotal assumptions. Earlier projections for SFY 2021 from State agencies and the House Ways and Means Committee were produced in late May and early June, and the State agencies updated their revenue projections in late July.[xvi]

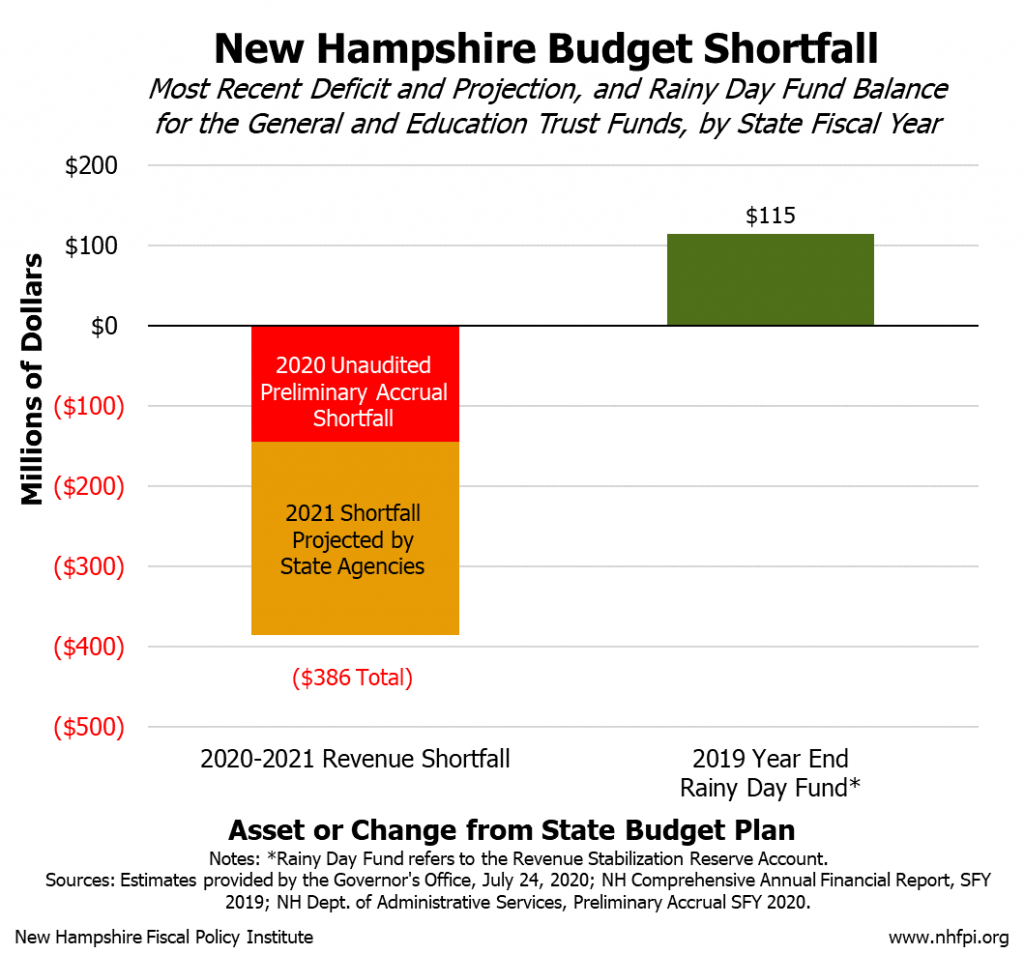

The July estimates suggest a General and Education Trust Funds revenue shortfall of about $385.6 million (7.3 percent), with a preliminary accrual shortfall of $143.9 million (5.5 percent) in SFY 2020 and a projected shortfall of $241.7 million (9.1 percent) in SFY 2021. This shortfall would dwarf the approximately $115 million in savings in the State’s Rainy Day Fund at the end of SFY 2019.

Alongside the General and Education Trust Funds shortfall, the Governor’s office calculated an estimated revenue shortfall, treating cost of collections separately, of $14.9 million in the Highway Fund. Additionally, the Turnpike Fund was projected to have a revenue shortfall of $16.3 million in SFY 2021, while the Fish and Game Fund was anticipated to have a small surplus in both years.

As calculated by State agencies and reported by the Governor’s office, in total across the General, Education Trust, Highway, Turnpike, and Fish and Game Funds, the expected shortfall in State revenue during the State Budget biennium would be $437.9 million. While these projections are more optimistic than State agency projections from late May 2020, and future updates to projections will likely show additional differences, these figures indicate a very significant revenue shortfall relative to expectations during the State Budget biennium.

The Shortfalls of the Great Recession

While significant, such a shortfall is not without precedent in the General and Education Trust Funds, which rely on revenue streams driven in part by economic activity. During the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, the SFYs 2008-2009 State Budget, as originally passed, experienced a significant shortfall relative to the original State Revenue Plan.[xvii] Based on the SFYs 2008 and 2009 preliminary accrual reports, which are most directly comparable to the figures available for SFY 2020 prior to final auditing, the revenue shortfall in the General and Education Trust Funds for SFYs 2008-2009 State Budget as passed was $384.4 million (8.3 percent), a similar dollar figure to the projected shortfall for SFYs 2020-2021, but a larger percentage of the total in the State Revenue Plan for those two funds combined.

The recovery from the Great Recession was slow, particularly in the early years of the economic expansion in New Hampshire.[xviii] This contributed to much smaller revenue shortfalls in subsequent years, although SFY 2009, which included the most acute period of the Great Recession, saw the largest shortfall by far. The economic recovery from the COVID-19 recession may look substantially different, and some early indicators suggest a much faster initial decline in the unemployment rates after a massive, historic spike unlike anything seen in the Great Recession. Unemployment in New Hampshire remains higher than at any point during or immediately following the Great Recession. While the initial recovery may be more rapid so far than the last recovery, the trajectory of job opportunities for workers and recovery of household incomes may slow considerably, and is likely dependent on both public health factors and the resources individuals have available to pay for housing, food, child care, and other necessities that enable them to engage in the economy.[xix]

With a slow recovery, a rebound in State revenues may remain sluggish into the next State Budget biennium. Even with a rapid recovery, revenue increases would be very unlikely to sufficiently offset losses during this State Budget biennium to cover the shortfall with savings in the Rainy Day Fund. Another revenue source would have to be employed to backfill the budget shortfall and avoid damaging reductions in State expenditures for needed programs and services.

Potential Federal Assistance

During both the 2001 recession and the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, the federal government provided financial assistance to states.[xx] State balanced-budget requirements, combined with falling state revenues, increase the risk of reduced public services and employment during a recession, which can create further economic damage and slow any recovery.[xxi] Aid from the federal government can help balance state budgets and provide effective economic stimulus.[xxii] The form of this federal aid, however, can have significant impacts on the ability of states to deploy aid to balance budgets and avoid service reductions.

Although the federal government has provided a significant amount of relatively flexible aid to states, important limitations on this aid restrict its ability to help balance the State Budget. The most significant flexible aid to New Hampshire came in the form of the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF). These CRF dollars, which totaled $1.25 billion in grants to New Hampshire, could be used for a wide variety of purposes and are currently being employed to support key health care, housing, and other assistance programs in New Hampshire.[xxiii] However, current federal guidance forbids the use of CRF allocations for paying for items funded in state and local government budgets approved prior to March 27, 2020, effectively preventing use of these funds to offset revenue shortfalls. CRF funds must also be spent or returned by December 30, 2020.[xxiv]

Unrestricted Aid

The federal government could supply direct, unrestricted aid to states. A bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in May 2020 would provide funding to states to offset revenue losses for the purpose of avoiding layoffs and harmful spending reductions that would occur due to revenue losses. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates the allocation to New Hampshire under this legislation in 2020 and 2021 would be $3.4 billion.[xxv]

Congress may also eliminate the current restrictions on aid previously allocated in the CARES Act CRF, permitting states to use these funds to offset state and local revenue losses. However, New Hampshire has already appropriated the majority of these funds to specific purposes, limiting the amounts that would be available to offset revenue losses.[xxvi]

Aid to Offset Other Budgeted Funds

Congress could temporarily increase the portion of the Medicaid program funded by federal transfers. Medicaid, a program funded jointly by state and federal governments, helps provide access to health services for more than 196,000 people with limited resources in New Hampshire.[xxvii] The total amount allocated to this program in New Hampshire was approximately $2.1 billion in SFY 2020, and most services are typically funded with 50 percent federal dollars and 50 percent State dollars, with certain programs receiving a higher share of support from the federal government.[xxviii] The federal government has increased the federal portion of the Medicaid match, also known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) in prior recessions, and has increased the FMAP by 6.2 percentage points for the duration of the current federal public health emergency.[xxix] The 6.2 percentage point increase will likely help offset the increased Medicaid enrollment costs seen in New Hampshire, but will likely not significantly offset previously-budgeted General Fund appropriations for the State portion of the Medicaid match.[xxx] An additional FMAP increase, which is an efficient and effective way to quickly send aid to states that offset General Fund costs, would help the State balance its budget.

Congressional proposals also include additional aid for local public education.[xxxi] To the extent any aid provided for local public education can be used to offset existing costs, additional federal aid may provide more fiscal relief to New Hampshire and better enable it to balance its budget.

Conclusion

As New Hampshire’s residents grapple with the upending impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, the State government is facing serious budget shortfalls. These shortfalls may have significant impacts on the State’s ability to provide the services Granite Stater’s need during this pandemic and its aftermath. While the revenue deficits may be managed over the remainder of this State Budget and into the next biennial spending plan, additional revenue will be needed in order to sustain the budgeted services that will be critical for helping Granite Staters weather this crisis. Policymakers may consider additional State revenue to assist the State Budget, particularly when considering funding the next biennium. However, direct aid from the federal government during this crisis, depending on its form, may quickly help ensure that key services be maintained.

Too many Granite Staters faced difficulty securing a stable future for themselves and their children prior to the pandemic. This crisis has exacerbated the needs for some, and created newfound hardship for many others. Additional revenue to fund key services in New Hampshire will be essential to support residents during and after this crisis, and to build a more equitable economy during the recovery.

Endnotes

[i] For information regarding income losses in New Hampshire since the beginning of the pandemic’s impacts locally, see NHFPI’s June 3, 2020 Common Cents post New Data Provide Insight into Extensive Economic Impacts and Income Losses from the COVID-19 Crisis and NHFPI’s presentation from August 19, 2020, State and Federal Funding in New Hampshire and the Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis.

[ii] For more information on the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, see NHFPI’s June 3, 2020 Common Cents post New Data Provide Insight into Extensive Economic Impacts and Income Losses from the COVID-19 Crisis, as well as NHFPI’s April 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[iii] See NHFPI’s presentation from August 19, 2020, State and Federal Funding in New Hampshire and the Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis.

[iv] In this document, the term “State Budget” is in reference to the State’s biennial operating budget as well as the language in the Trailer Bill. For more information on components of the State Budget, see NHFPI’s September 2017 Issue Brief Measuring the Size of New Hampshire’s State Budget.

[v] For more information on the General and Education Trust Funds, see NHFPI’s Building the Budget resource.

[vi] For more information on the ways in which the State collects revenue, see NHFPI’s Revenue in Review resource.

[vii] For both State monthly cash revenue and preliminary accrual data, see the New Hampshire Department of Administrative Services Monthly Revenue Focus publications.

[viii] To see analysis of behavior in business tax receipts following the federal tax overhaul, see NHFPI’s 2019 Issue Briefs Funding the State Budget: Recent Trends in Business Taxes and Other Revenue Sources and Business Tax Revenue and the State Budget.

[ix] For more information, see NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Funding the State Budget: Recent Trends in Business Taxes and Other Revenue Sources.

[x] For more information, see RSAs 77-A and 77-E for requirements related to the requirements and timing of returns, estimates, and extensions. For planned monthly receipts, see the New Hampshire Department of Administrative Services, Division of Accounting Services, Revenue Plans by Fiscal Year. Also, see NHFPI’s May 2019 Issue Brief Funding the State Budget: Recent Trends in Business Taxes and Other Revenue Sources.

[xi] See NHFPI’s April 3, 2020 Common Cents post March State Revenues Underperform Ahead of Coming Declines and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s March 21, 2020 announcement Treasury and IRS Delay Federal Tax Day from April 15 to July 15 Due to COVID-19 Outbreak.

[xii] See the New Hampshire Department of Administrative Services Monthly Revenue Focus for July SFY 2021.

[xiii] See the New Hampshire Department of Administrative Services Monthly Revenue Focus, Preliminary Accrual for June SFY 2020.

[xiv] Estimates provided to NHFPI by the Governor’s Office, July 24, 2020.

[xv] See NHFPI Issue Briefs The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 and The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xvi] See NHFPI’s May 29 Common Cents post State Agencies Project Major Revenue Declines Due to COVID-19 Crisis Impacts and July 23, 2020 presentation New Hampshire’s Budget Shortfalls and Future Federal Relief. July State agency estimates provided to NHFPI by the Governor’s Office, July 24, 2020.

[xvii] The Great Recession began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. As such, that national-level economic contraction, as delineated by the National Bureau of Economic Research in September 2010.

[xviii] For more information on the economic recovery from the Great Recession in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s June 2018 Issue Brief New Hampshire’s Economy: Strengths and Constraints.

[xix] For more information on New Hampshire’s economy and the COVID-19 crisis, see NHFPI’s June 3, 2020 Common Cents post New Data Provide Insight into Extensive Economic Impacts and Income Losses from the COVID-19 Crisis, as well as NHFPI’s April 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses. See also NHFPI’s presentations from May 27, 2020, New Hampshire’s Economy and the COVID-19 Crisis: An Early Overview, and from August 19, 2020, State and Federal Funding in New Hampshire and the Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xx] For more information and references, see The Pew Charitable Trusts September 2019 Fact Sheet: How the Federal Government and States Coordinate in Times of Recession.

[xxi] For additional discussion, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities March 2016 report Preparing for the Next Recession: Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

[xxii] For more information on policies to stimulate economic recovery, see NHFPI’s April 29, 2020 Common Cents post Key Policies Provide Short-Term Relief and Long-Term Recovery in COVID-19 Crisis.

[xxiii] For details on the deployment of CRF dollars in New Hampshire, see the website for the Governor’s Office for Emergency Relief and Recovery and NHFPI’s May 22, 2020 Common Cents post Majority of New Hampshire’s Federal CARES Act Flexible Grants Appropriated, Includes Added Support to Businesses, Nonprofits, and Child Care.

[xxiv] See NHFPI’s April 23, 2020 Common Cents post Federal Guidance Prevents Use of CARES Act Relief Funds for State Revenue Shortfalls.

[xxv] For more information, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities May 28, 2020 Fact Sheet How Much Would Each State Receive Through the Coronavirus State Fiscal Relief Fund in the Heroes Act?

[xxvi] For details on the deployment of CRF dollars in New Hampshire, see the website for the Governor’s Office for Emergency Relief and Recovery and NHFPI’s May 22, 2020 Common Cents post Majority of New Hampshire’s Federal CARES Act Flexible Grants Appropriated, Includes Added Support to Businesses, Nonprofits, and Child Care.

[xxvii] Medicaid enrollment figures as of the end of July 2020. For more information about Medicaid in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

[xxviii] Medicaid total cost figures for SFY 2020 provided by the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant in August 2020.

[xxix] For more information on aid in past recessions, see The Pew Charitable Trusts September 2019 Fact Sheet: How the Federal Government and States Coordinate in Times of Recession. For more information on the current FMAP increase, see the Kaiser Family Foundation’s July 2020 Issue Brief How Much Fiscal Relief Can States Expect From the Temporary Increase in the Medicaid FMAP?

[xxx] This expectation was reported by the Governor’s office in late July 2020.

[xxxi] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities May 28, 2020 Fact Sheet: How Much Would Each State Receive Through the Coronavirus State Fiscal Relief Fund in the Heroes Act? and the Yale School of Management Program on Financial Stability, Senate Republicans introduce HEALS Act, next round of COVID-19 response, August 6, 2020.