According to data released on September 9 by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), food insecurity levels in New Hampshire continued to decline during 2019, prior to the onset of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. The report outlines the trends of reduced food insecurity in the nation and in New Hampshire, declining from the higher levels resulting from the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. The overall improvements to the state economy through 2019, along with the effectiveness of key nutritional aid programs, did contribute to lower levels of food insecurity, although the benefits of the economic recovery did not reach all Granite Staters in an equal or timely manner. Although food insecurity levels declined through the years preceding 2020, the current crisis facing Granite Staters is not reflected in these 2019 data. The recent economic pressures on many individuals and families with lower incomes in New Hampshire have been severe, and current levels of food insecurity are very likely to be substantially higher.

Food Insecurity Prior to the COVID-19 Crisis

Data in the USDA report released on September 9, 2020 are collected through the Current Population Survey’s Food Security Supplement. This questionnaire is distributed to households throughout the country to estimate food security at national and regional levels. According to the USDA, food insecurity means that “households were, at times, unable to acquire adequate food for one or more household members because they had insufficient money and other resources for food.” To collect sufficient information to reliably estimate the percentage of households that are food insecure, three years of survey data are combined at the state level to calculate an estimate. This three-year time span is necessary at the state level to provide adequate data for meaningful analysis, which is particularly important for small population states like New Hampshire.

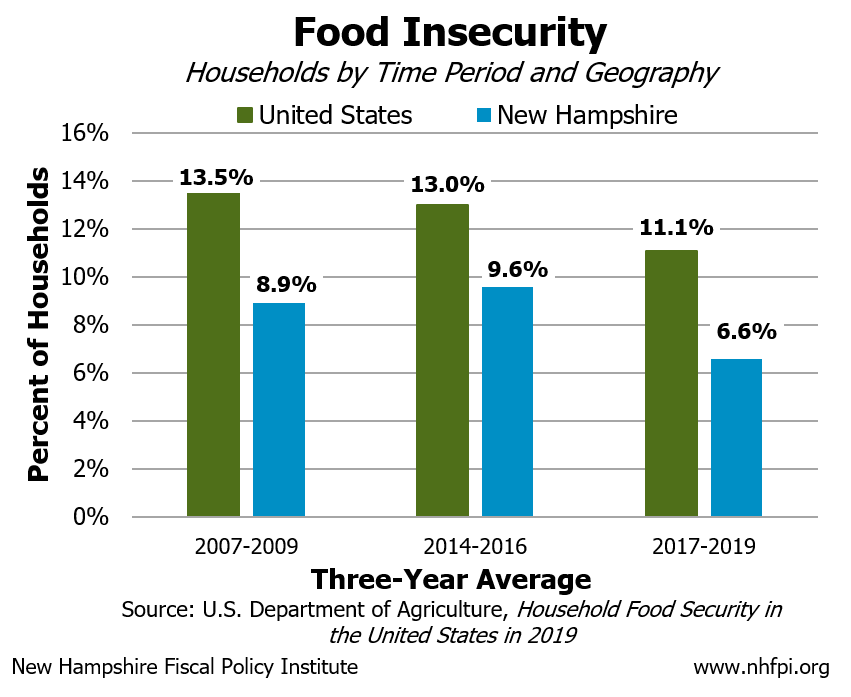

In New Hampshire, 6.6 percent of households were estimated to be food insecure during the 2017-2019 period. This represents about 35,500 households where food insecurity was reported at least once in the past year. This figure is a reduction from the higher levels of estimated food insecurity experienced throughout the state from 2014 to 2016, where an estimated 9.6 percent of households were food insecure. This decrease in food insecurity is a statistically significant change, indicating a high probability the sample data reflects an actual change in conditions even when accounting for the limited sample sizes and the resulting margins of error. The 2007-2009 period, which includes the Great Recession but is prior to the low point in the state’s economy, had an estimated food insecurity level among households of 8.9 percent in New Hampshire. The 2017-2019 level of food insecurity dropped, in a statistically significant fashion, below levels experienced both during and immediately prior to the Great Recession. Compared to the nation overall, New Hampshire had lower levels of food insecurity over all periods in the last 15 years. However, food insecurity levels remained elevated for a longer period of time in New Hampshire, compared to the nation overall, during the recovery from the Great Recession.

The Current Food Insecurity Landscape

The continued decline in estimated levels of food insecurity through the 2017-2019 period may be attributed to the growing state economy during this time, and to the effectiveness of nutritional aid programs such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP). However, the current COVID-19 crisis has resulted in extensive risks to the health and economic wellbeing of many Granite Staters. Particularly notable are declines in employment and losses in income that may have resulted in, and continue to result in, financial pressures on individuals and families, which may result in increased food insecurity.

In April, the U.S. Census Bureau collected the first phase of weekly survey data targeted at understanding the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on households. This first phase of the weekly Household Pulse Survey was conducted from April 23 to July 21 where the data was released weekly. A second phase of surveys and data collection has just begun, and is expected to run from August 19 to October, with data disseminated every two weeks.

Based on the responses from the first phase of the survey, the U.S. Census Bureau has estimated widespread income losses among Granite Staters since the pandemic began. Over these initial 12 weeks, nearly half of New Hampshire respondents reported a reduction in household income from employment since March 13, 2020. During mid-July, about one in five households expected a decline in incomes during the next four weeks because of the pandemic. The first release of data from the second phase of the survey indicates that many of the challenges experienced by Granite Staters lingered into late August as well. Over the period from August 19 to August 31, about one in five households expected a decline in income during the next four weeks because of the pandemic, and about five percent of households indicated they sometimes or often had not enough to eat in the last seven days.

Looking Ahead

The most recently released food insecurity estimates for 2019 do not incorporate the current crisis, but do indicate that a decreasing proportion of New Hampshire households were experiencing a lack of adequate food prior to the COVID-19 crisis. Declining levels of food insecurity were consistent through 2019, since peaking during the slow recovery from the Great Recession in the early to mid-2010s. However, the current COVID-19 crisis, and the resulting economic pressures facing many Granite Staters with lower incomes, may result in increased levels of food insecurity in New Hampshire. Programs aimed at assisting individuals and families by providing nutritional aid are effective at reducing food insecurity and stimulating the economy as well. Policies helping to ensure that Granite Staters can access nutritional assistance may help mitigate an increase in food insecurity throughout the COVID-19 crisis, while boosting the economic recovery.

– Michael Polizzotti, Policy Analyst