First published in New Hampshire Bulletin, September 7, 2023; also published in Manchester Ink Link and Concord Monitor.

Since 2015, state revenues have increased substantially. These higher revenues have provided opportunities for investments in health, education, and transportation while generating surpluses over planned revenue targets in state budgets and giving policymakers more fiscal space to enact tax rate reductions.

State lawmakers have successively reduced the business profits tax (BPT) and the business enterprise tax (BET) rates. The BPT taxes profits after certain adjustments, while the BET is based largely on compensation businesses pay to employees.

Between state fiscal years 2015 and 2022, combined BPT and BET revenues rose 118 percent. Concurrently, BPT and BET rates were reduced incrementally in tax years 2016, 2018, 2019, and 2022. The 2015 BPT and BET rates were 8.5 percent and 0.75 percent, respectively, and are at 7.5 percent and 0.55 percent for tax year 2023.

At the NH Fiscal Policy Institute, we sought to explore why tax revenues have increased. As the BPT is the state government’s largest tax revenue source, understanding the reasons for this increase could offer key insight into the state’s fiscal policy future, as these revenues have enabled investments in services and resource-sharing with municipalities.

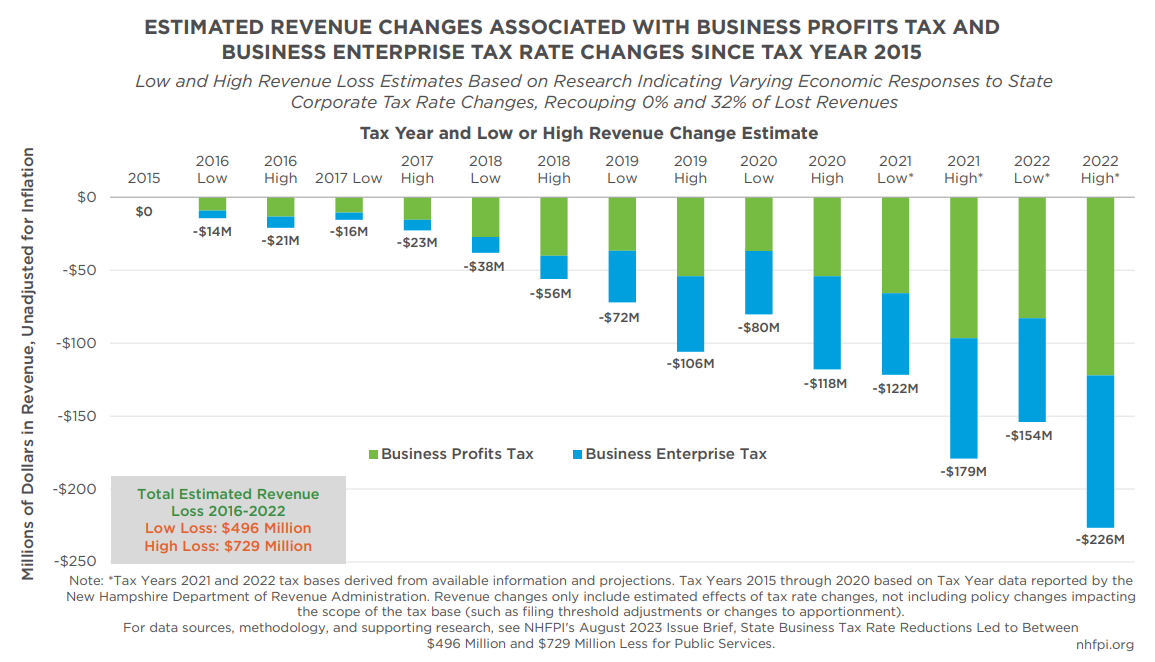

We did not find evidence the tax rate reductions spurred sufficient economic growth to offset tax revenue losses or to increase business tax revenues. We estimated that revenue losses totaled between $496 million and $729 million across tax years 2016-2022. While revenues grew during this time, the state lost revenue to these rate reductions that it would have otherwise collected if the rates had not changed.

As explained in our recent Issue Brief, six key pieces of evidence support this conclusion.

First, while BPT revenues increased during this time, BET revenues stagnated. Available state data show BET receipts were lower in tax years 2019 and 2020 than in 2015, before the rate reductions.

Second, from the creation of the BPT in 1970 through 2022, there is no statistically significant relationship between the tax rate and job growth, or between the tax rate and gross state product growth in New Hampshire relative to New England overall. If the rate reductions spurred sufficient growth to offset revenue losses, economic responses to lower rates would likely be detectable. Personal income per capita, after adjusting for consumer price inflation in New England, grew similarly across Maine, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire between 2015 and 2022.

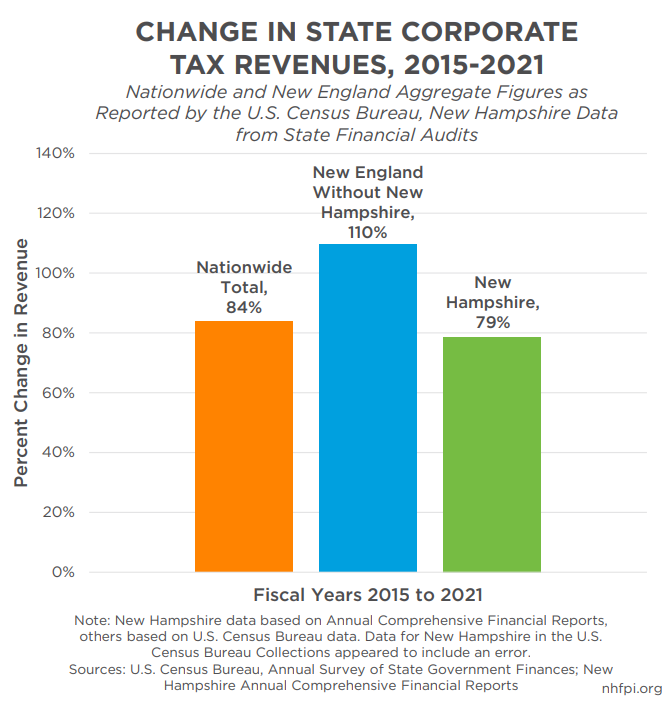

Third, combined state-level corporate tax revenues in other New England states, as well as nationally, rose 110 percent and 84 percent, respectively, between fiscal years 2015 and 2021, while New Hampshire business tax revenues increased 79 percent in the same period. The Granite State’s recent revenue increase is far from unique, which makes it unlikely to have been caused by state policy changes.

Fourth, multi-national entities pay the majority of BPT revenue, making their corporate profits a key part of the tax base. National corporate profits have surged since 2015, and particularly since the pandemic’s beginning, due to influences beyond New Hampshire policy.

Fifth, while the number of business tax filers increased between 2015 and 2020, revenues rose much faster, suggesting growth was not primarily driven by an influx of businesses.

Sixth, research from other states and nationally, including peer-reviewed academic analysis published between 2013 and 2022 as well as research from government entities and private-sector organizations published between 2010 and 2023, does not indicate reducing state corporate tax rates is likely to increase revenue, or have a dramatic effect on economic activity overall.

This evidence does not eliminate the potential for business tax rate reductions to help the economy, but does reflect the math of the tax rate reductions themselves. For all but the most profitable entities, the BPT rate reductions are likely insufficient to enable hiring more employees. For example, using the most recently available tax year 2020 data, for the 8,123 businesses that paid between $1,000 and $10,000 in BPT (representing 43 percent of all BPT-paying businesses), the average tax reduction if that rate had been one percentage point lower would have been $504.

Additionally, because multi-national entities that pay the majority of BPT revenues and their ownership may be anywhere, the benefits of a BPT reduction may flow to out-of-state shareholders, rather than being reinvested here.

Other research suggests that New Hampshire’s economy could be more effectively stimulated by services or tax reductions targeted at residents with lower incomes, who would use more of those resources locally. For example, evaluating U.S. policy choices in 2021, Moody’s Analytics estimated that each public dollar spent on food assistance for low-income households would have generated $1.61 in economic growth that year, while a corporate tax rate reduction would have generated only $0.32 for every dollar.

As policymakers look to opportunities in the next state budget, data-driven and research-informed policy decisions can help create a more effective and efficient government, supporting economic growth and promoting the well-being of Granite Staters.

Phil Sletten is the research director at the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit, independent policy research organization based in Concord and focused on the state budget, New Hampshire’s economy, and policies affecting Granite Staters, particularly those with low and moderate incomes. Learn more at nhfpi.org.