This second edition of New Hampshire Policy Points provides an overview of the Granite State and the people who call New Hampshire home. It focuses in on some of the issues that are most important to supporting thriving lives and livelihoods for New Hampshire’s residents. Moreover, the book addresses areas of key policy investments that will help ensure greater well-being for all Granite Staters and a more equitable, inclusive, and prosperous New Hampshire.

New Hampshire Policy Points is intended to provide an informative and accessible resource to policymakers and the general public alike, highlighting areas of key concerns. Touching on some important points but by no means comprehensive, each section within New Hampshire Policy Points includes the most up-to-date information available on each topic area. The facts and figures included within this book provide useful information and references for anyone interested in learning about New Hampshire and contributing to making the Granite State a better place for everyone to call home.

To purchase a print copy or download a free digital PDF of New Hampshire Policy Points, visit nhfpi.org/nhpp

A healthy population contributes to more vibrant economies, lower health care costs, and increased lifespans. Health includes both individual and population level factors that go far beyond formalized health care. Health is influenced by the social determinants of health, which include one’s neighborhood, social status, educational access, health care quality, safety, financial resources, and more.[1] The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services defines these social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that affect a wide range of health risks, health outcomes, and quality of life.”[2]

For example, income is a key indicator of resources available to individuals and families, which can impact health substantially.[3] Income allows people to address their basic needs, such as food and housing, which in turn influences the health status of individuals and families. Households with lower incomes, particularly below or near poverty levels, are more likely to be food insecure and lack access to nutritious foods.[4] People with low incomes are also more likely to have difficulty keeping up with the costs of prescription drugs and medical care.[5] Additionally, people with low incomes experience difficulty in securing safe and affordable housing, and have an increased risk of being exposed to environmental pollution and hazardous material.[6] Social determinants of health impact the lives of all individuals, and are affected by the systems designed to provide health care to Granite Staters.

Access to Health Coverage and Services

Many New Hampshire residents have relatively good access to health care services, but other residents, particularly those in rural areas, may face additional barriers.[7] Access to primary care varies considerably within the state. While there were only 530 people per every one primary care physician in Grafton County in 2021, there were 2,080 people for each one in Belknap County, with the ratio of patients to providers in the state’s other eight counties falling between those two benchmarks.[8] Limited primary care availability may mean that Granite Staters must wait longer to obtain appointments with their doctor or travel farther to access health care services. In 2019, New Hampshire residents living in rural areas, outside of southeastern New Hampshire, were almost two times more likely than those living in non-rural areas to travel more than thirty minutes one-way for a primary care visit.[9] But these concerns are not limited to primary care, as Granite Staters may have to travel farther for specialty care services as well. For example, the availability of maternity care in New Hampshire’s rural regions is a significant concern. Between 2000 and 2021, nine out of New Hampshire’s sixteen rural hospitals closed their labor and delivery units. An analysis from the Urban Institute indicated that, as a result of these closures, the median driving time to the nearest labor and delivery unit in the Granite State doubled from 2000 to 2018.[10]

The level of health care availability and quality can affect how often one can visit their provider and use health care services. Delaying needed health care also has implications for the state’s labor force and economy. According to national data from the Urban Institute, about 15 percent of working age adults who delayed care during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced limitations in their ability to work.[11]

The frequency of obtaining care in New Hampshire varies. In 2022, just over three in four Granite State adults had visited a doctor for a routine appointment in the previous twelve months, however, about one in 22 reported last seeing a doctor five or more years prior.[12] Additionally, about one in ten reported not having a personal care provider in 2022.[13] Granite Staters who are not able to access preventive care on a regular basis may have their life expectancy impacted due to an increased risk of chronic health conditions and mortality. Although the life expectancy of a Granite Stater was relatively high in 2020, at about 79.5 years old, life expectancy varied by county, with residents in three out of ten counties, Belknap, Coos, and Strafford, experiencing significantly lower life expectancies at 77.6, 77.2, and 78 years, respectively.[14] In 2021, Belknap County and Strafford County had the largest population to primary care provider ratios, indicating that limited access to care might be related to lower life expectancies.[15]

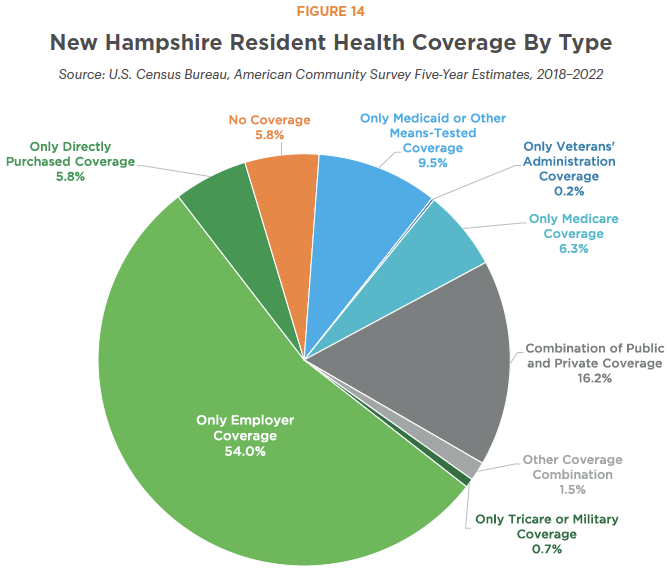

Even when health care providers are available nearby, many Granite Staters may not have the financial resources to access these services. About 60.5 percent of New Hampshire’s population relied solely on private health insurance during 2018 to 2022. These individuals included approximately 54.0 percent of all Granite Staters who had coverage solely through their employer, and about 5.8 percent who relied only on insurance purchased directly, including through the individual insurance marketplace.[16] About 78,768 Granite Staters, or about 5.8 percent of all residents, did not have health coverage of any form. That figure rose to about 11.2 percent for Granite Staters with incomes below the federal poverty threshold.[17]

The remainder of Granite Staters accessed health services through public insurance or a combination of public and private coverage. Data from 2018 to 2022 suggest about one in five New Hampshire residents (20.3 percent) were enrolled in Medicare, with about 6.3 percent of all residents relying on Medicare as their only health coverage.[18] Generally, adults aged 65 years and older are eligible for health coverage under the federal Medicare program.

Medicaid

Medicaid, a program distinct from Medicare, is a federal-state partnership designed to provide health insurance coverage to certain populations who may not otherwise have an avenue for accessing health care, including people with low incomes, those who have a disability, who are children, and who are pregnant. At the end of June 2024, 183,774 New Hampshire residents were enrolled in Medicaid, or about 13 percent of the estimated 2023 state population. This total included 9,308 adults over 64 years old and 88,914 children, including children with severe disabilities or in foster care.[19]

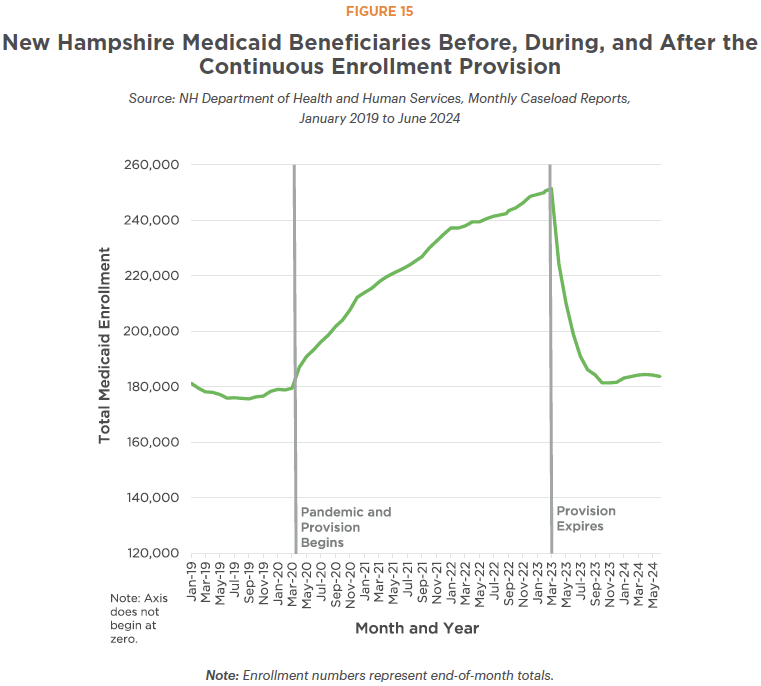

Although one in eight state residents are covered through Medicaid, the total number of beneficiaries in June 2024 was smaller compared to the same month in every year since 2019. Access to Medicaid was temporarily but substantially expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic through a continuous enrollment provision, which permitted beneficiaries to be continuously enrolled in Medicaid after their initial qualification and enrollment date, regardless of any change in their eligibility status during that time.[20] Upon expiration of continuous enrollment on April 1, 2023, New Hampshire began disenrolling people from Medicaid through a process known as the “unwind.”[21]

The total number of Granite Staters enrolled in Medicaid reached its peak at the end of March 2023, with 251,491 total enrollees. Medicaid enrollment dropped by about 26.7 percent in the year following the beginning of the unwind, dropping to 184,255 total enrollees by the end of March 2024. Medicaid’s Granite Advantage Health Care eligibility group, which provides coverage to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines, faced the sharpest declines since the beginning of the unwind, with more than one in three (38.5 percent) losing coverage between March 2023 and March 2024.[22] Enrollees impacted by the unwind also included some residents who were receiving behavioral health care coverage through Medicaid.[23]

Behavioral Health

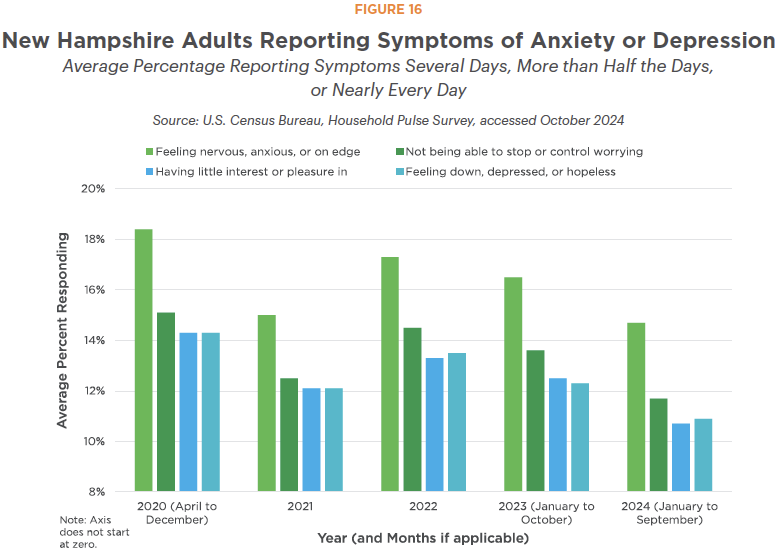

Mental health can have a profound impact on overall health. Survey data suggest that about three in ten New Hampshire adults experienced symptoms of either an anxiety or depressive disorder in 2020.[24] Comparatively, national data suggested about one in ten adults had anxiety or depressive disorders in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.[25] While the percentage of Granite State adults reporting symptoms decreased in the first half of 2024 compared to 2020, a higher number were experiencing symptoms than prior to the pandemic.[26]

The percentage of high school students reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression was similar to the percentage of adults reporting such symptoms during the pandemic. In 2021, about 36 percent of high schoolers in the Granite State experienced symptoms, with this percentage decreasing to about 32 percent in 2023.[27]

New Hampshire faces challenges providing needed mental health care. Hospital patients in the state may face a considerable waiting period for mental health services to become available as need has outpaced capacity.[28] In recent years, New Hampshire has made significant investments, including the establishment of statewide mobile crisis response units for children, to help address these growing needs. Despite investments, access to mental health providers varies throughout the state. While there were 170 people per every one mental health provider in Grafton County in 2021, there were 470 people for each one in Coos County based on total population counts, with the ratios of patients to provider in the state’s other eight counties falling between those benchmarks.[29]

Substance misuse has also had a deep impact on the Granite State. The number of people in New Hampshire who died in a drug-related death was almost four times that of the number of people who died in a highway motor vehicle accident in each year between 2016 and 2022. During this time, drug overdose deaths peaked in 2017 with 490, and remained elevated at 486 confirmed deaths in 2022.[30] Unfinalized data for 2023 and 2024 suggest the number of people dying from drug overdoses may have declined from 2022, but still remains similar to annual deadly overdoses in the 2019-2021 period.[31] The number of people receiving substance use disorder services through Medicaid each month slightly decreased between early 2020 and late 2023, after more than doubling between late 2016 and early 2020.[32] That number has continued to remain steady since the pandemic began, as both health and economic strains exacerbated stress on individuals and families.

Granite Staters with Disabilities

Based on data collected from 2018 to 2022, about one in eight, or 12.9 percent, of Granite Staters experienced a disability. Among those with a disability, including Granite Staters with multiple disabilities, about 43.3 percent experienced difficulty with mobility, about 40.3 percent with cognition, about 32.6 percent with independent living, about 30.5 percent with hearing, about 15.4 percent with self-care, and about 15.1 percent with vision.[33]

Older adults are more likely to have some form of disability. In New Hampshire, more than one in five adults aged 65 to 74 years had some form of disability during the 2018 to 2022 period, as did about 43 percent of adults aged 75 years and older.[34] For older adults with low incomes and limited assets, Medicaid funds long-term services and supports, both in nursing facilities and in homes or communities.[35] As New Hampshire’s adults age over the next two decades, the need for health care, transportation, and housing services will likely increase.

• • •

This publication and its conclusions are based on independent research and analysis conducted by NHFPI. Please email us at info@nhfpi.org with any inquiries or when using or citing New Hampshire Policy Points in any forthcoming publications.

© New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, 2024.

Endnotes

[1] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Healthy People 2030, Social Determinants of Health.

[2] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services, Access to Opportunity.

[3] See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ February 2017 summary, Income and Health Outcomes.

[4] See the NHFPI’s February 29, 2024 issue brief, Poverty and Food Insecurity in New Hampshire During and Following the COVID-19 Crisis.

[5] See the Kaiser Family Foundation’s March 1, 2024 issue brief, Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs.

[6] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Healthy People 2030, Housing Instabilityand the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Justice and Air Pollution.

[7] See the Commonwealth Fund’s 2023 Scorecard on State Health System Performance and the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s May 16, 2023 article, Why Health Care is Harder to Access in Rural America.

[8] See the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute’s data tool, County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Primary Care Physicians.

[9] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ December 27, 2022 report, Annual Report on the Health Status of Rural Residents and Health Workforce Data Collection.

[10] See the Urban Institute’s October 27, 2021 brief, Following Labor and Delivery Unit Closures in Rural New Hampshire, Driving Time to the Nearest Unit Doubled.

[11] See the Urban Institute’s February 2021 report, Delayed and Forgone Health Care for Nonelderly Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

[12] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, BRFSS Prevalence and Trends Data, Health Care Access and Coverage.

[13] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, BRFSS Prevalence and Trends Data, Health Care Access and Coverage.

[14] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ data portal, Life Expectancy and Mortality.

[15] See the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute’s data tool, County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Primary Care Physicians.

[16] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Private Health Insurance Coverage, S2703.

[17] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage, S2701.

[18] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Public Health Insurance Coverage, S2704.

[19] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ July 3, 2024 report, New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography.

[20] See the NHFPI’s April 30, 2024 blog, Granite Staters Continue to be Impacted by End of Continuous Medicaid Enrollment One Year Later.

[21] See the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service, Unwinding and Returning to Regular Operations after COVID-19.

[22] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ July 3, 2024 report, New Hampshire Medicaid Enrollment Demographic Trends and Geography.

[23] For example, see the Community Behavioral Health Association’s analysis of disenrollment presented to the February 12, 2024 meeting of the NH Medical Care Advisory Committee.

[24] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. Note: 2020 data only includes survey data collected from April through December of that year.

[25] See the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anxiety and Depression: Household Pulse Survey.

[26] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

[27] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ data portal, Youth Risk Behavior Survey Results.

[28] For example, the NH Department of Health and Human Services reported that, as of August 30, 2024, 19 adults were in emergency departments waiting for acute psychiatric beds to become available.

[29] See the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute’s data tool, County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Mental Health Providers.

[30] See the NH Office of Chief Medical Examiner’s 2022 report, Summary of 2022 New Hampshire Drug Overdose Deaths and the U.S. Department of Transportation’s 2022 report, State Highway Safety Report: New Hampshire.

[31] See the NH Office of Chief Medical Examiner’s 2022 report, Summary of 2022 New Hampshire Drug Overdose Deaths, and the NH Department of Health and Human Services New Hampshire Drug Monitoring Initiative, June 2024 Report published August 1, 2024.

[32] See the NH Department of Health and Human Services’ June 20, 2024 Operating Statistics Dashboard.

[33] See the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Disability Characteristics, S1810.

[34] See the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Disability Characteristics, S1810.

[35] See the NHFPI’s July 18, 2022 publication, Long-Term Services and Supports in New Hampshire: A Review of the State’s Medicaid Funding for Older Adults and Adults with Physical Disabilities.