Robust workforces can help create strong, prosperous economies. The size of New Hampshire’s labor force, composed of individuals working or actively looking for work, has not returned to the pre-pandemic levels of 2018 and 2019. New Hampshire’s labor force is constrained by a variety of factors, including limited access to housing and child care, as well as a significant number of residents reaching traditional retirement ages and an overall older population relative to most other states. Available data suggest barriers to labor force participation and higher wage-earning opportunities for women, particularly women of color, are key constraints to both individual and overall economic prosperity.

Women in the Granite State Labor Force

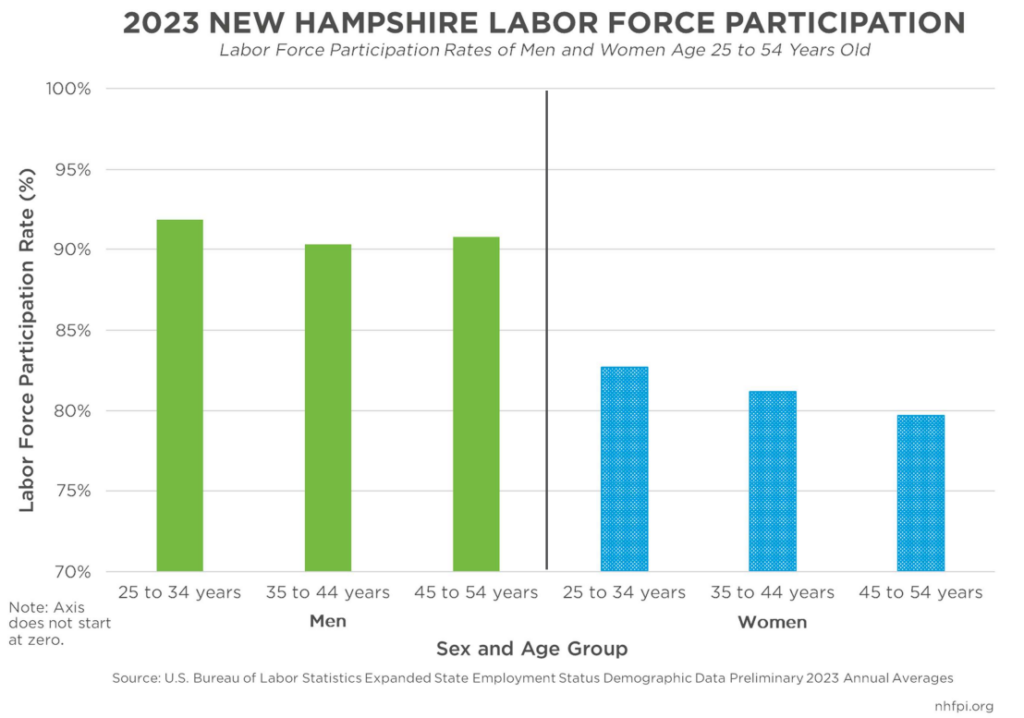

In 2023, New Hampshire labor force participation among women between the ages of 25-54 years old was approximately 10 percent lower (81.2 percent) than among men of the same age (91.2 percent). In these U.S. Census Bureau data, the terms “men,” “women,” “male” and “female” are used to reflect the language used by the Bureau in its definition of sex and in survey data collection.

The most recent data suggest that, in 2023, females were 46.4 percent of New Hampshire’s labor force, while males comprised the other 53.6 percent. Despite being a smaller proportion of the labor force, women held 51 percent of the jobs based in the state in early 2023. Taken together, these data suggest woman were less likely to participate in the labor force than men, but when they did, were less likely to commute out of state for employment and were more likely to hold multiple, possibly part-time, positions. National data indicate part-time jobs are much less likely to offer benefits for health insurance and retirement.

In 2022, the median annual earnings for men working full-time and year-round in New Hampshire was about $73,322, 32.8 percent higher than women’s median annual earnings of approximately $55,206 that same year. Due to data limitations, earnings data cannot be disaggregated by race and sex; however, white, non-Hispanic Granite Staters had higher average estimated per capita incomes during the 2018 to 2022 period ($49,300) than American Indian and Alaska Native residents ($40,200), individuals identifying as another race not listed in the survey ($34,100), Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander residents ($33,800), individuals identifying as of two or more races ($31,500), Black or African American Granite Staters ($30,700), and Hispanic or Latino individuals of any race ($30,300). Asian Granite Staters were the only group that earned a higher mean annual income ($58,300) than white, non-Hispanic residents. Relative to these data, the U.S. Census Bureau defines race and ethnicity separately, with ethnicity describing whether an individual identifies as Hispanic or Latino or not.

Pay gaps by gender and race may exist for a variety of reasons, including the higher likelihood of women and people of color to engage in unpaid or low-paying caregiving roles.

Women and Mothers in Paid and Unpaid Caregiving Roles

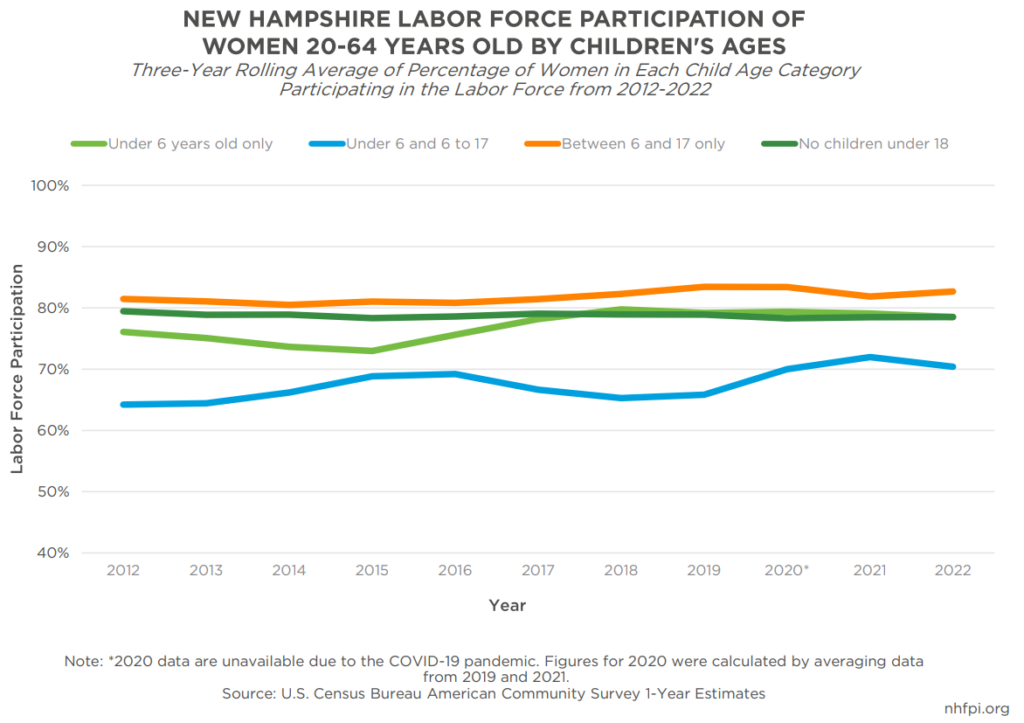

Being a mother, especially to multiple children, is a key contributing factor to lower labor force participation rates among Granite State women. From 2012 to 2022, women with a child(ren) under six and a child(ren) between the ages of 6 and 17 consistently had the lowest labor force participation rate among women ages 20 to 64, with three-year rolling average rates ranging between 64 and 72 percent.

A higher proportion of women work in caregiving professions that often have lower pay, particularly in the sectors of early childhood education and older adult care. Additionally, women are more likely to engage in unpaid labor, including caring for children or older family members, which may contribute to lower workforce engagement among Granite State women. Earning lower wages and engaging in unpaid labor can have adverse long-term financial implications for women, particularly during retirement years, as well as for the overall economy. When examining the economic impact of women engaging in full-time unpaid caregiving, optimizing the specialization of labor should also be considered; in other words, unpaid caregivers may have unique skillsets that could be better utilized in different, paid employment roles for those who desire to be in the labor force but may not be able to do so for financial reasons.

Between June 2023 and June 2024, an average of approximately 5.8 percent of individuals not in the Granite State labor force reported they were caring for a child who was not in school or child care (about 16,700 people), or for an older adult (about 4,600 people). Although these data are not disaggregated by sex, the national U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that two of every three caregivers are women. If this proportion is applied to New Hampshire data, about 14,200 women may have been out of the labor force because they were providing unpaid caregiving. This statistic does not account for individuals who are in the labor force but work reduced hours to provide care to a family member.

If the 2023 median annual earnings for all New Hampshire occupations ($49,980 for a full-time worker earning the median hourly wage) was applied to the estimated 14,200 women outside of the labor force engaging in unpaid caregiving labor between May 2023 and May 2024, there may have been a collective loss of approximately $710 million in earnings for Granite State women. These earnings could have provided financial support for women and their families as well as served as financial stimuli for local and State economies.

Women’s Participation in Caregiving Roles

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in the first quarter of 2023, approximately 91 percent of employees providing New Hampshire’s child care services and nearly 88 percent of employees in the home health care services sector were women. During this period, Black or African American Granite Staters were overrepresented in the home health care services, representing 4.5 percent of employees in the sector compared to 2.1 percent of the New Hampshire population.

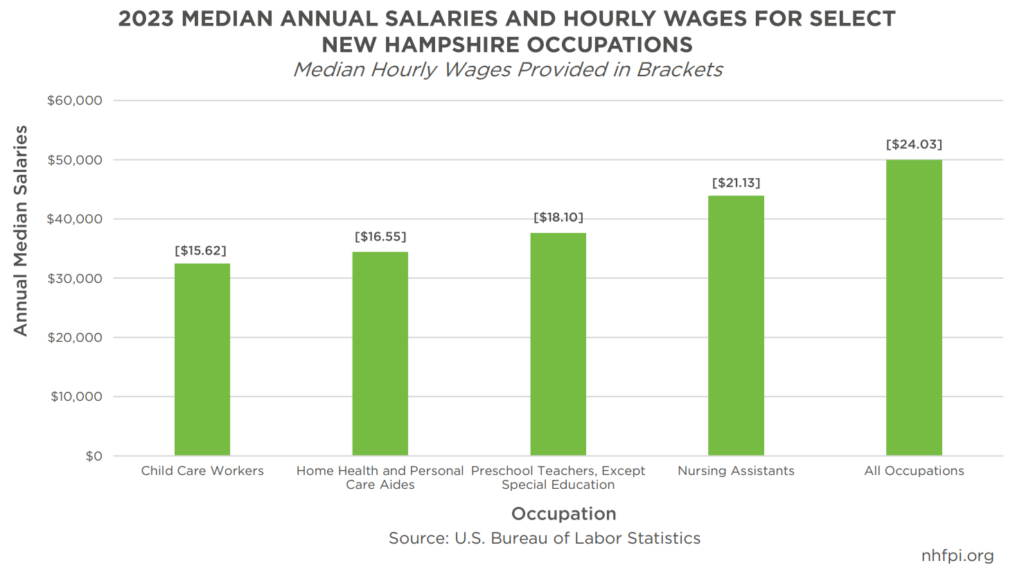

Earnings for many occupations within these sectors are below the Granite State’s median income for all occupations. For example, the 2023 median annual earnings for all New Hampshire occupations, assuming full-time employment at the median hourly wage, was $49,980. Using the same methodology based on median hourly wages, however, child care workers earned a median salary of $32,490, and home health and personal care aides were paid $34,420.

The average price of child care for two children under five in New Hampshire was nearly $31,900 a year in 2023. The 2024 statewide annual private pay rate for nursing facilities, including atypical and specialized care, is approximately $141,700 per year, according to State data. For families with a worker earning at or below the annual salaries of employees in caregiving occupations, staying home to care for family members who might otherwise be in a child care setting or a nursing facility may be more financially practical than engaging in paid employment. This calculation by families may help to explain why mothers with multiple young children have lower labor force participation rates compared to other women, even mothers with older children. Additionally, pursuing a higher-paying occupation that is less physically, socially, and emotionally taxing could be appealing to some potential workers, further contributing to labor shortages in home health care services and early childhood care and education.

Economic Impact and Policy Considerations

The Granite State economy and labor force are negatively impacted when families cannot afford child or older adult care. Families lose potential income, and the state’s labor market remains more constrained because potential workers are out of the labor force, or individuals work fewer hours than they would otherwise, to care for family members. Reduced workforce participation may become a larger challenge over time as the population ages and New Hampshire becomes home to more older residents who need care.

Individual family members, particularly women, may be adversely impacted when they must stay home to care for family members. Analyses funded by the U.S. Department of Labor estimated in 2023 that mothers may earn 15 percent less in lifetime earnings, including federal Social Security and retirement plan payments that are dependent on pre-retirement earnings from work, than they would have if they did not engage in any caregiving. Additionally, 2024 estimates suggest that men age 66 years and older had 32.6 percent more retirement income than women of the same age, which can increase the likelihood of older women living in poverty who may require subsidies and services.

Key policies may help ease the challenges faced by women engaging in paid and unpaid caregiving, including some that have been recently enacted by New Hampshire policymakers. The recent eligibility expansion for the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program has the potential to make child care more affordable for families with low and moderate incomes, including those who work in caregiving sectors. A household of four in 2024 earning up to approximately $113,400 annually can participate in the program and pay no more than seven percent of their income toward their child care cost share. New Hampshire’s Legislature also increased State Budget funding by an estimated 50.7 percent for the Choices for Independence Medicaid program, which supports older adults who choose to age in their homes or communities instead of moving into more expensive nursing facility settings. By making child care and care for older adults more affordable, the Granite State may be able to expand its labor force with potential employees who currently engage in unpaid caregiving.

Other policies may help address the differences in male and female labor force participation and earnings. As part of the State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 State Budget, New Hampshire allocated $15 million in one-time funding for child care recruitment and retention. This initiative may help child care businesses provide bonuses or other recruitment and retention benefits to their workers to help keep and grow their staff. Informed by the outcomes of this initiative, additional investments through similar policies may help ensure better pay for individuals in caregiving sectors. The added funding may also help reduce staffing shortages that limit access to these services, contributing to the need to have individuals stay home part- or full-time in a care-taking capacity

Finally, policies that help ensure all employees have flexible scheduling with advance notice of changes may allow more caregivers to engage in the labor force. Being able to take paid sick days to care for oneself or a family member helps ensure individuals with caregiving responsibilities can take time off without losing pay. Additionally, having access to a predicable work schedule well in advance of work shifts may allow caregivers to better plan for their family members’ care so they can engage in paid work.

The Granite State has made some progress toward addressing employment and wage gaps between men and women through a variety of fiscal policies. Additional policies that help ensure long-term investment in the child care and health care professions, particularly among the lowest-paid workers in these sectors, may encourage more potential workers to join the workforce. A robust workforce and jobs that pay higher wages benefits New Hampshire’s economy and residents.

– Nicole Heller, Senior Policy Analyst