The child care industry provides well-established economic and child development benefits. When parents cannot work due to unmet child care needs, the size of the potential workforce declines, and local and state economies suffer. U.S. Census Bureau survey data collected between March 2023 and March 2024 suggest that, on average, nearly 15,500 New Hampshire residents were not employed each month because they were caring for a child not in school or in a child care setting.[1] Additionally, in 2021, an analysis from the Bipartisan Policy Center estimated that New Hampshire households collectively lost between $400 million and $600 million in wages, or approximately $441 million and $661 million in inflation-adjusted 2023 dollars, respectively. When potential business losses and government tax revenues were added to the model, an estimated $44,100 to $66,816 per unavailable child care slot was lost (or $48,611 to $73,634 in 2023 dollars).[2] Shortages of this nature may also have impacts across multiple generations, as grandparents may work less, or leave the labor force entirely, to help care for their grandchildren.[3]

Beyond allowing parents to work, high quality early childhood care and education (ECE) provides long-term benefits to children’s development and strong returns on investment, especially among children in families with low incomes. Key research suggests three- and four-year-olds who attend quality ECE have better short- and long-term developmental outcomes, including enhanced language, literacy, mathematics, and socioemotional skills with some children demonstrating up to a full year of additional learning from enrollment in high-quality ECE as preschoolers.[4] Longitudinal research suggests this type of education contributes to higher educational attainment, higher wages, lower health care costs, reduced need for public assistance, and lower likelihood of engagement in criminal activity later in life.[5]

Despite the importance of child care, the economics of the industry are fragile and do not function like typical markets for goods and services. Traditional economic theory postulates that when supply is low and demand is high, prices increase. As the supply of a good or service increases to become readily available relative to the demand for it, prices begin to decrease. The child care industry, however, does not function as traditional economic theory would suggest. In New Hampshire and elsewhere, there is currently a high demand for child care slots, but a low supply of availability. This occurrence dictates a higher price for a product or service, but the current child care business model cannot charge the true cost of providing high-quality care. Most programs cannot raise prices high enough to cover the costs of providing their crucial services and still have enough families who can afford to purchase child care. The result of these fragile economics is that parents pay high prices for tuition, but child care programs typically make little or no profit, while early childhood educators receive low wages. As a result, efforts to increase supply may be economically unattractive to child care businesses: increase tuition prices, further decrease ECE educator wages, or run child care programs at a deficit increasing the likelihood of business closures.

This Issue Brief provides a multi-faceted examination of the child care economy in New Hampshire, reviewing key challenges facing the child care sector, and the economic constraints associated with the industry. This Brief describes the concept of “true cost of care” and illustrates why high-quality care often requires providers to exceed their operating budgets to successfully implement their programs. Finally, this Brief examines Granite State initiatives currently being utilized to address the fragile child care economy, as well as solutions being explored by other states.

Limited Supply and High Demand

New Hampshire’s child care supply is limited. Between 2018 and 2022, New Hampshire had a yearly average of 54,242 children under age six with both parents, or their sole parent, in the workforce who may have needed child care.[6] During this time period, there was an average of approximately 45,800 licensed child care slots, resulting in an average annual shortage of about 8,400 slots in these five years.[7]

During this time frame, the number of available child care slots remained relatively stable (a reduction of approximately 144 slots); however, there was just under an 11 percent reduction in the number of providers during these years (approximately 89 fewer programs) suggesting a shift to fewer, but larger, child care providers across the state.[8] Within that timeframe, in 2019, between 24 and 31 percent of surveyed New Hampshire parents reported there were not adequate options for child care where they lived, with median-income families reporting fewer options.[9]

Child care shortages may be more severe than the above licensed capacity calculations suggest. Many providers may not be enrolling at their full licensed capacity levels for a variety of reasons. For example, in March 2023, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) reported a child care staff vacancy rate of 26 percent.[10] When there are not enough early childhood educators available to hire, providers may need to close classrooms. In certain cases, individual behavioral differences among children may require that a provider reduce the number of children in a classroom to help ensure each child has enough teacher support to thrive in the program. Decreasing the number of children in a classroom can also help reduce educator burnout, thus enhancing employee retention in the field.

Finally, shortages across the state are common but may be more severe in some municipalities, counties, and regions. In March 2024, 6.1 percent of New Hampshire’s municipalities (home to about 85,000 residents) had no licensed or licensed-exempt providers, while 10 percent (populated by about 140,300 residents) had only one.[11] An October 2021 report noted that even in areas of high child care access like Manchester and Greater Derry, there was still only one child care slot for every two children. The lowest access was in Central New Hampshire and the Lakes Region, where there was approximately one child care spot available for every four to five children.[12]

High Prices for Families

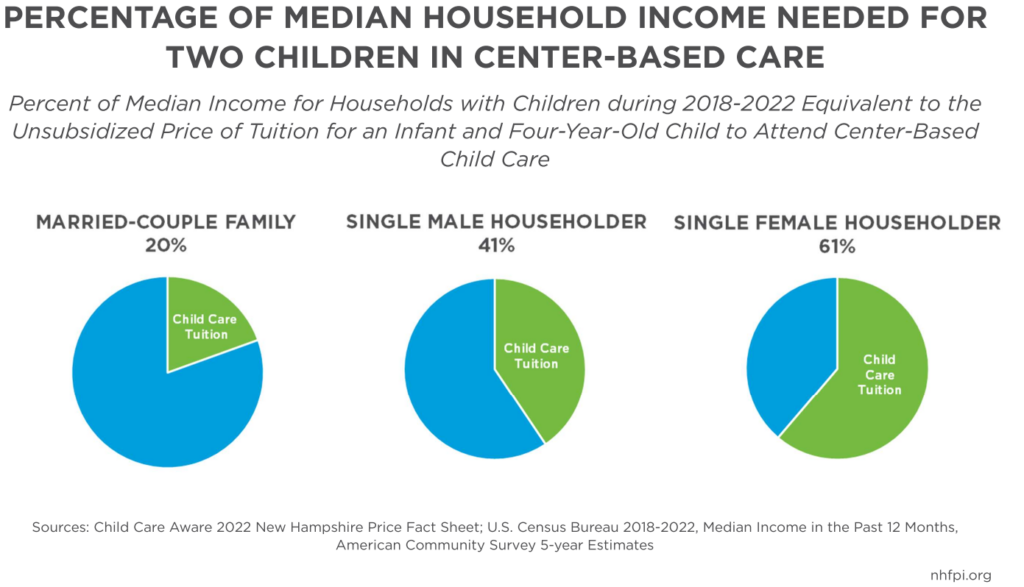

The average annual price for an infant and four-year-old child in center-based care in New Hampshire was $31,868 in 2023, a 12.5 percent increase from $28,340 in 2022.[13] Based on the most recently available U.S. Census Bureau income data collected during the 2018-2022 period, married-couples earning the median income ($145,289) in New Hampshire would have needed to spend nearly 20 percent of their household income on child care for an infant and four-year-old child at the 2022 prices, while single male ($69,830) and female ($46,283) householders would have needed to spend 41 percent and 61 percent, respectively.[14] These percentages are based on households paying the full price of tuition, and not accounting for subsidized tuition through the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship (NHCCSP) or other programs.

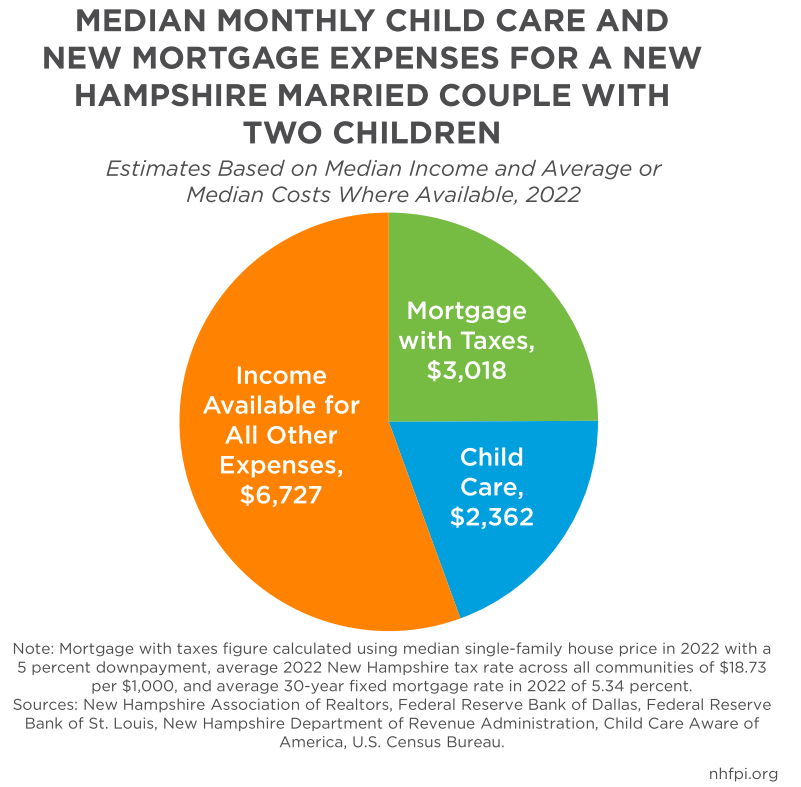

Affordable child care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is defined as no more than 7 percent of a household’s income.[15] To meet this definition of affordable child care a Granite State family with these two children would have needed to earn an annual household income of $404,857 in 2022 and $455,257 in 2023.[16] When child care prices are paired with New Hampshire’s record-breaking house sale prices and high mortgage interest rates, families may need to devote a significant portion of their household income toward child care and housing expenses. For example, a median-income married couple family with children earned $145,289 annually ($12,107 monthly) in 2022.[17] If this couple had two children under four in center-based child care, the 2022 estimates suggest they paid, on average, $2,362 monthly for child care.[18] If this family purchased a median-priced single-family house in 2022, they would have a monthly mortgage of $3,018 (including property taxes).[19] Altogether, this family would spend 44 percent of their household income on mortgage and child care payments alone, leaving only 56 percent ($6,727) for all other expenses.

According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator, in 2024, two working adults with two children in New Hampshire would need to spend an additional $6,344 each month on other typical cost of living expenses, including food, medical expenses, and transportation, leaving just $383 left over each month for savings or emergency expenses.[20] As these estimates are based on a median income married-couple family, half of New Hampshire’s families with two children will have less than that amount left over each month. For many young Granite State families, high housing and child care costs may effectively require choosing between buying a home or having a child.

Low Wages for Child Care Workers

Although tuition for child care is beyond the federal government’s affordability benchmark for many families in the Granite State, most programs are not charging families the “true cost of care.” True cost of care for child care providers encompasses all traditional business expenses as well as those necessary to provide a stimulating environment and curriculum for children and families, meet licensing requirements, create profit margins similar to those of other small businesses, and pay early childhood educators professional wages. Child care programs can only charge tuition rates that local families can afford, and as a result, child care workers are often paid based on the amount that remains after paying other required expenses.

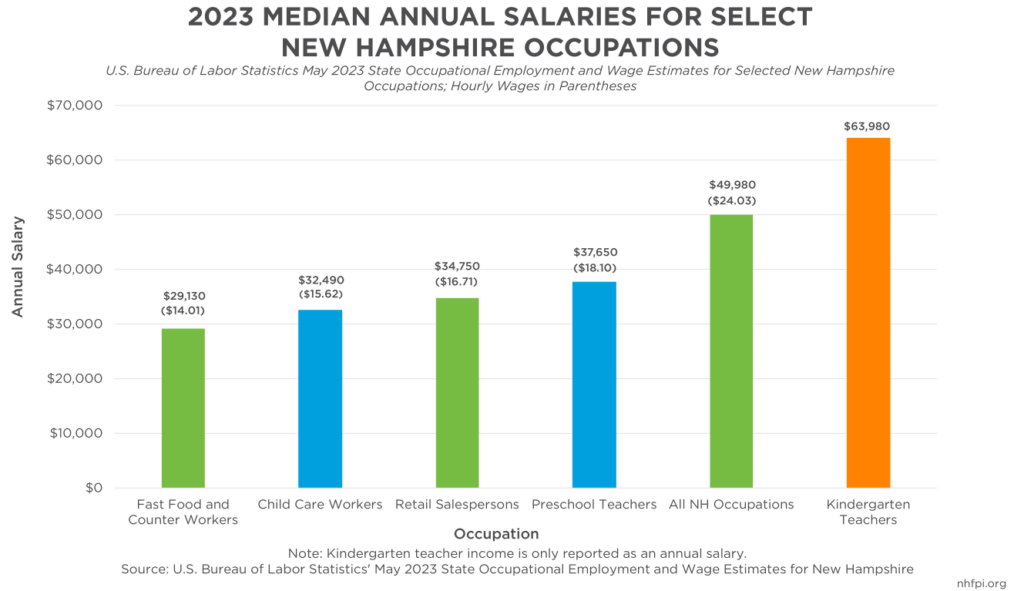

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) categorizes child care staff into three categories: “child care workers,” “preschool teachers, except special education,” and “education and child care administrators, preschool and daycare”. In 2023, the median hourly wage for a New Hampshire child care worker was $15.62 an hour. This equates to $32,490 annually, only $2,500 more than the 2023 federal poverty guideline for a family of four, and approximately half of the 2023 median salary for New Hampshire’s kindergarten teachers.[21] New Hampshire’s preschool teachers earned a median annual salary of $37,650 in 2023, which is $2,900 more than retail salespersons, but approximately $12,000 less than the median annual salary and wage income of all New Hampshire occupations.[22] Education and child care administrators earned median salaries of $60,210 in 2023, slightly less than half the median salary for all Granite State Management Occupations ($120,650).[23] New Hampshire’s child care services are mostly provided by women, with an approximate 10 woman to 1 man ratio in the field during the first three quarters of 2023.[24] Because much of the child care workforce is composed of women, the low wages associated with roles in this profession further existing inequities for women in the Granite State.[25]

Additionally, due to limited revenue, programs may not be able to provide benefits to their workers, which may result in increased need for subsidy use by these employees. A national 2023 report from the U.S. Administration for Children and Families’ Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation revealed that only 23 percent of child care and early education teachers working in center-based care received health insurance benefits through their employer, while 14 percent used public health insurance, 18 percent were uninsured, and the rest received coverage through direct private coverage purchases, a spouse’s insurance plan, or a combination of sources.[26] Low wages and few, if any, benefits are likely key factors contributing to the child care workforce shortage, as workers can earn considerably more income doing other work. For parents in the child care workforce, staying home with their own children may be a better financial decision for a family, compared to making just enough at a job to pay their children’s child care tuition.

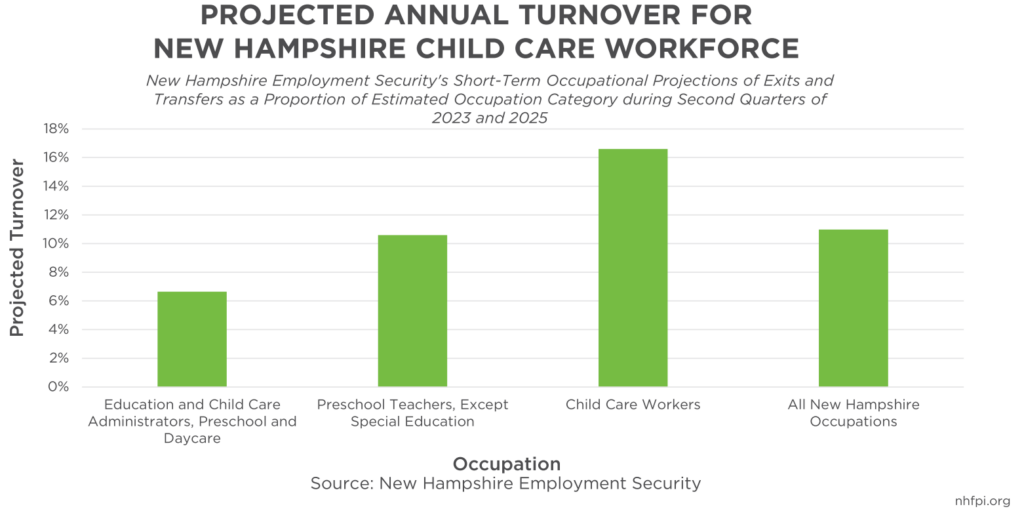

Low wages and no benefits are likely key contributing factors to high turnover rates among early childhood educators. Turnover among child care workers in New Hampshire is projected to be 17 percent annually from the second quarters of 2023 to 2025, compared to 11 percent for all New Hampshire occupations.[27] These projections are in addition to any child care worker positions that need to be filled due to growth in the sector, which is projected to be just under one percent through the second quarter of 2025.[28]

Ensuring Safety and Quality

The current child care business model is strained, with available research suggesting many providers make less than one percent in revenue to reinvest in their businesses.[29] Unlike other businesses, child care providers are limited in the ways they can streamline or consolidate their operating expenses. For example, a child care center cannot add more children to a classroom to reduce operating costs if there is not adequate space or staff to support the additional children. Increasing the child-teacher ratio may negatively impact safety and quality of care, and thus, the State of New Hampshire’s Child Care Licensing Unit (CCLU) maintains smaller child-teacher ratios. Additionally, New Hampshire CCLU requires that providers have a minimum of 40 square feet of indoor floor space per child in each room used by children.[30]

To increase the capacity of child care slots, providers must add more space, more teachers, or both to their programs. Adding more space is challenging, particularly if a program currently utilizes all available space in their building. Increasing space may require constructing an addition or obtaining more property to expand. Adding more teachers may be possible if providers currently have space to expand; however, given the workforce shortage in New Hampshire, hiring is also challenging for providers.[31] These factors complicate supply in the child care economy.

Creating a high-quality caregiving and educational environment also requires considerable resources. High quality care and education includes positive child-teacher and child-child interactions, developmentally appropriate materials and activities that stimulate cognitive development and support learning, curricula and assessments adapted to meet the needs and interests of students in the classroom, regular professional development for teachers and staff, and strong parent-teacher partnerships.[32] To encourage programs to provide high quality ECE, the majority of states in the United States use quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS).[33] New Hampshire’s QRIS is called Granite Steps for Quality (GSQ).[34] GSQ is a voluntary program that began in Spring 2022 and focuses on two components of quality: staff qualifications and learning environments.[35] The program replaced New Hampshire’s previous QRIS, which used a three designation system with levels denoting Licensed, Licensed Plus, and Accreditation.[36]

To join the program, providers must achieve several prerequisite steps that include licensing their child care program, having the program administrator view several training videos, and enrolling to participate in the NHCCSP.[37] To earn subsequent steps in the program (up to 4), providers and their staff must meet a variety of criteria in the areas of 1) staff qualifications and 2) learning environments. For example, step 1 has multiple components for center-based providers, including administrators and 20 percent of program staff holding a current NH Early Childhood Credential as well as completion of professional development trainings related to learning environments.[38]

Each additional criterion step requires increased staff involvement as well as engagement with different quality activities, such as consultations with a program coach, engagement with active quality improvement plans, and on-going professional development for staff and administrators. Criteria differ for family child care, center-based early childhood programs, and out-of-school time programs.[39] As of Spring 2024, 124 out of 716 licensed New Hampshire child care programs (17.3 percent) had a step designation.[40]

Participation in the GSQ program comes with financial incentives that encourage programs to enroll and maintain enrollment in the GSQ program. The incentives include, depending on step designation and other factors, between 5 and 10 percent of a program’s NHCCS billing, quarterly quality incentives that range from $600 to $5,700, and access to a GSQ Commitment to Quality Annual Award.[41] Incentive funds can be used for a variety of quality-related purposes and include, but are not limited to, materials for children or staff, furniture, playground equipment, building and grounds improvements, family events, and staff bonuses. Approximately $11.5 million in federal funds have been appropriated to support GSQ incentives and GSQ program infrastructure in the State Fiscal Years 2024-2025 State Budget, with approximately $10.0 million designated specifically toward grants for public assistance and relief.[42] If these $10.0 million for potential incentive payments were equally divided among all of New Hampshire’s approximately 700 licensed programs, each program would receive approximately $7,000 per provider per year if all providers were enrolled in the program.

This amount of incentive funding may not be enough to address additional costs incurred when providing high-quality care.[43] Implementing high-quality programs can involve multiple adjustments to a provider’s operating budget, including staff training and professional development, group size, and teacher time outside of the classroom. For example, hiring more qualified teachers and staff requires offering higher wages to be more competitive, as well as offering more paid time off and other benefits. Creating high-quality classrooms might require reducing group sizes for younger children or suppressing classroom sizes to serve children with higher needs; however, engaging in these practices increases the cost of care per child, as the cost of keeping the classroom open is divided among fewer families. Finally, giving teachers time to engage in quality-enhancing activities like professional development, curriculum planning time, and family engagement may require programs to hire additional teachers or staff to be with children while teachers participate in these activities outside of the classroom.

New Hampshire Solutions

The last of the approximately $29 million federally-funded American Rescue Plan Act – Discretionary (ARPA-D) funds, which are intended to support investments in New Hampshire’s child care infrastructure, will expire in September 2024 and may impact the stability of the Granite State’s child care sector.[44] Nearly $48 million in federally-funded ARPA-Stabilization funds, which were designed to stabilize the child care industry during the COVID-19 pandemic, expired on September 30, 2023. Addressing challenges within the child care economy comprehensively will require a multi-pronged approach. The Granite State currently has several initiatives in place that may help address some of the challenges being experienced by New Hampshire’s child care programs.

The recently expanded income eligibility for the NHCCSP may make child care affordable for more families. This expansion both raised the income eligibility cap to 85 percent of the officially-defined State Median Income and reduced family cost share rates to no more than seven percent of a family’s household income.[45] Additionally, federal and State funding is currently supporting projects designed to increase outreach and advertising of the NHCCSP, as well as strengthen the infrastructure of family resource centers across the state.[46] For child care providers, there are a variety of pilot programs targeted at addressing the health of child care business models, facility improvements, and partnerships between employers and child care businesses.[47]

With regard to the child care workforce, there are currently several early childhood career pathways in New Hampshire that have low or no-cost tuition options to earn assistant, associate, and lead teacher qualifications, as well as some programs that train ECE directors.[48] Among these pathways are grant programs offered through the Community College System of New Hampshire that provide tuition assistance to individuals pursuing careers in ECE or are currently employed by a licensed provider.[49] In addition, a portion of ARPA-D funding was allocated for multiple child care workforce recruitment and retention projects. Projects include several studies examining the unique characteristics and needs of New Hampshire’s child care workforce, development of a comprehensive list of low-cost self-care, wellness, and mental health support programs for ECE staff and teachers, and professional development trainings.[50] Finally, the SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget allocated $15 million to be distributed directly to child care providers. These grant funds are intended to support the child care workforce by providing funding to child care programs to support their teachers, administrators, and staff through wage increases or sign-on bonuses, student loan repayments, credits toward health insurance plans, or deposits into a Health Savings or Flexible Spending Accounts.[51]

Additional Policy Considerations and Conclusion

Due to the multidimensional nature of the child care economy, exploring additional policy initiatives may be an effective strategy to help ensure the long-term sustainability and health of the child care sector in New Hampshire. One potential strategy would be to increase employer investments in the child care sector. The incentives for business investment include an expanded workforce and revenue increases from workers spending their incomes locally.[52] Employer-employee or employer-child care partnerships may also be an effective approach and could involve child care cost sharing between an employer, a parent, and the State; employers purchasing child care slots for their employees at a nearby child care program; or an employer collaborating with an established child care business to provide on-site child care.[53]

Looking to successful programs in other states may also help generate ideas for programs that are a good fit for the Granite State. For example, Kentucky expanded its Child Care Assistance Program (Kentucky’s form of child care scholarships) to include individuals working in licensed child care centers or family child care homes, regardless of income, if they worked an average of twenty hours per week or more.[54] Washington, DC and Maine both developed programs to provide direct stipends to all child care workers. Washington, DC’s Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund supplemented ECE teachers’ standard wages with up to an additional $14,000 a year depending on a teacher’s employment and staffing category.[55] Maine approved $12 million in recurring State dollars to continue providing child care worker stipends after starting the fund with ARPA-Stabilization dollars from 2022.[56] Finally, New Mexico took a comprehensive approach to child care sector challenges by using its Land Grant Permanent Fund to help ensure families at or below 400 percent of the federal poverty guidelines receive free child care. Additionally, New Mexico allocated $10 million in grants intended to increase child care availability in child care deserts, and $2,000 per semester stipends for every early childhood professional earning an advanced degree in early childhood.[57]

As one-time federal funding to New Hampshire’s ECE sector ends in September 2024, the industry will likely need additional investment to meet demand due to the fragile nature of the child care economy. While the expanded eligibility of the NHCCSP will help make child care costs more affordable for families, there is still a shortage of available child care slots and workers. Without investments to address supply challenges, families may struggle to access quality child care for their children. These challenges extend to the entirety of the Granite State as individuals who do not have access to child care cannot join the New Hampshire workforce and help build a more vibrant New Hampshire economy.

Endnotes

[1] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data collections from Week 56 to Phase 4.0 Cycle 03.

[2] Note: These figures include the financial loss from the first year of the unavailable child care slot as well as residual, cumulative effects related to those initial financial losses over a ten-year time horizon. See Bipartisan Policy Center’s 2021 report, The Economic Impact of America’s Child Care Gap, in particular, p. 11 for an explanation of cumulative impacts. Figures adjusted for inflation using CPI-U New England.

[3] See the 2013 peer-reviewed paper from IZA Journal of Labor Policy, Grandparents’ Childcare and Female Labor Force Participation, the National Bureau of Economic Research’s 2024 working paper, The Multigenerational Impact of Children and Childcare Policies, 2022 peer-reviewed paper from The Journal of Human Resources, Grandmothers’ Labor Supply, and the New Hampshire Women’s Foundation February 13, 2013 Testimony. Note: Much of the research in this area has been conducted in other high-income countries that share some characteristics with the United States; however, caution must always be exercised when generalizing research cross-culturally. For example, the NBER working paper reports that a Canadian universal child care program in Quebec increased employment rates among mothers and grandmothers, suggesting there may be multi-generational effects on the labor force. Due to the significant public investments in the affordability of child care in Canada since 2021, informal care by grandparents is less common, which may explain the small effect sizes in the analyses. The small effect present in this analysis may be larger if applied to the U.S. where informal care by grandparents is more common.

[4] See Society for Research in Child Development and Foundation for Child Development’s October 2013 summary Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education, Child Development Perspectives’ 2022 peer-reviewed article, The Promise and Purpose of Early Care and Education, National Bureau of Economic Research’s 2021 working paper, The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston later published in 2022 under the same title in the peer-reviewed journal The Quarterly Journal of Economics, and the Journal of Political Economy’s 2020 peer-reviewed article, Quantifying the Life-Cycle Benefits of an Influential Early-Childhood Program.

[5] See the Tax Policy Center’s September 2023 publication The Return on Investing in Children: Helping Children Thrive.

[6] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table B23008: Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangements by Employment Status of Parents.

[7] See 2-6-2024 data provided by NH Child Care Licensing Unit to the NH Child Care Advisory Council. Note on analysis: The number of children with two parents, or their sole parent, in the workforce may be an overestimate as not all families may want to use child care.

[8] See data provided by NH Child Care Licensing Unit to the NH Child Care Advisory Council on 6-8-2023 and 2-6-2024. Note on the analysis: The number of children with two parents, or their sole parent, in the workforce may be an overestimate as not all families may want to use child care.

[9] See 2020 NH Early Childhood Needs Assessment Final Report, p. 61.

[10] See Item FIS 23 124 from March 29, 2023 prepared for the New Hampshire Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee by New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

[11] Figures rendered from NHFPI original analysis of 733 of 736 New Hampshire child care providers. List of providers downloaded from NH Connections on March 25, 2024. U.S. Census Bureau’s July 1, 2022 Population Estimates Program estimates used for municipality population estimates.

[12] See the October 2021 report, New Hampshire’s Early Childhood System in the Time of COVID-19: Child Care Access and Regional Systems Coordination, p. 13–14.

[13] See 2022 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire and 2023 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire from Child Care Aware of America.

[14] Original NHFPI analyses using U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).

[15] See p. 3 of September 30, 2016 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Office of Child Care Final Rule in Rules and Regulations.

[16] NHFPI original analyses using 2022 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire and 2023 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire from Child Care Aware of America and U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).

[17] See U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).

[18] NHFPI original analyses using 2022 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire from Child Care Aware of America and U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).

[19] Mortgage estimated using New Hampshire Real Estate Network Single-Family Residential Home Sales 2022 median price of $440,000 with a 5 percent downpayment of $22,000, average 2022 New Hampshire property tax rate across all communities of $18.73 per $1,000, and average 30-year fixed mortgage rate in 2022 of 5.34 percent from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Mortgage estimated using Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Payment Calculator. Calculation does not include PMI or monthly homeowner’s insurance. Also see 2022 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire from Child Care Aware of America and U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Table S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).

[20] See Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator for New Hampshire last updated February 14, 2024.

[21] See U.S Bureau of Labor Statistic’s May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for New Hampshire and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation 2023 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (except Alaska and Hawaii).

[22] See U.S Bureau of Labor Statistic’s May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for New Hampshire.

[23] See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for New Hampshire Management Occupations.

[24] See U.S. Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators Explorer – New Hampshire.

[25] See Economic Policy Institute’s November 2021 report, Setting higher wages for child care and home health care workers is long overdue and the Bipartisan Policy Center’s 2021 report, Characteristics of the Child Care Workforce.

[26] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation’s November 2023 report, Health Insurance Coverage of the Center-Based Child Care and Early Education Workforce: Findings from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education.

[27] Note: Turnover was calculated by combining exits from the workforce with transfers to other occupations. See New Hampshire Employment Security’s Short-term Employment Projections, 2023 Q2 to 2025 Q2 and New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute’s April 2024 Data Byte, Annual Turnover Among Child Care Workers Projected to be 17 Percent.

[28] See New Hampshire Employment Security’s Short-term Employment Projections, 2023 Q2 to 2025 Q2

[29] See p. 16 in the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s September 2021 report, The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States.

[30] Note: Programs licensed before November 23, 2008, are permitted to be licensed with 35 square feet per child. Please see p. 44 in NH Child Care Program Licensing Rules (Adopted April 21, 2022).

[31] See NHFPI’s March 21, 2024 presentation, The Economy, Workforce, and Health Care Employment in New Hampshire and NHFPI’s March 28, 2024 Data Byte, New Hampshire’s Labor Force Did Not Grow in 2023.

[32] See the 2021 Child Development peer-reviewed article, Adult outcomes of sustained high-quality early child care and education: Do they vary by family income?, National Association for the Education of Young Children’s article, What Does a High-Quality Preschool Program Look Like?, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families’ Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation’s 2023 Report, Children’s Learning and Development Benefits from High-Quality Early Care and Education: A Summary of the Evidence, and the American Academy of Pediatrics 2017 Policy Statement, Quality Early Education and Child Care From Birth to Kindergarten.

[33] See the American Academy of Pediatrics 2017 Policy Statement, Quality Early Education and Child Care From Birth to Kindergarten. and Child Care Aware of America’s 2013 report, We Can Do Better: Child Care Aware of America’s Ranking of State Child Care Center Regulations and Oversight.

[34] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration’s March 2023 presentation, Granite Steps for Quality.

[35] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services posting on NH Connections, Granite Steps for Quality Advisory Committee.

[36] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services NH Connection’s webpage NH’s Quality Recognition and Improvement Systems (QRIS).

[37] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration’s March 2023 presentation, Granite Steps for Quality, p. 11.

[38] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration’s March 2023 presentation, Granite Steps for Quality, p. 17.

[39] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration’s March 2023 presentation, Granite Steps for Quality, p. 13-23.

[40] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ NH Connections’ webpage New Hampshire Child Care Search.

[41] See New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Bureau of Child Development and Head Start Collaboration’s March 2023 presentation, Granite Steps for Quality, p. 25.

[42] See Chapter 106, Laws of 2023 (House Bill 1), p. 538.

[43] See U.S. Government Accountability Office’s May 2023 Report, Child Care: Observations on States’ Use of COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Funding.

[44] See NHFPI February 2024 Issue Brief, The State of Child Care in New Hampshire: End of One-Time Federal Investments May Reduce Industry Stability.

[45] See NHFPI January 19, 2024 Blog, New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Eligibility to be Expanded in 2024, Provider Reimbursement Rates.

[46] See Governor and Executive Council Item 24 from June 2023 and Item 14 August, 2023. 2023.

[47] See Governor and Executive Council Item 17 from June 2023, Items 17 and 18 from August 2023.

[48] See New Hampshire 2022 Child Care Services Association report, Careers in Early Care and Education: A New Hampshire Directory, p. 20 and segments at 6:55 and 14:19in Early Learning New Hampshire’s Zoom Call with the Child Care Community from November 9, 2023.

[49] See Community College System of New Hampshire’s Early Childhood Grant Programs and Early Childhood Education Tuition Assistance webpages as well as the New Hampshire Child Care Advisory Council’s February 8, 2024 Zoom meeting at the 1:17:25 mark.

[50] See Governor and Executive Council Item 16 from June 2023.

[51] See Chapter 79, Laws of 2023 (House Bill 2), p. 148 and New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services’ Child Care Workforce Grant Overview.

[52] See Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s March 20, 2024 article, Can employers play a larger role in solving the nation’s child care crisis?

[53] See Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s March 20, 2024 article, Can employers play a larger role in solving the nation’s child care crisis?

[54] See the State of Kentucky Law, Title 922, Chapter 002, Regulation 160, Section 4.

[55] See Washington, DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education’s Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund webpage, accessed April 2024.

[56] See State of Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services September 2022 Press Release, Maine DHHS Announces $13. 6 Million in New Grants to Support Maine’s Child Care Providers, and April 2022 Press Release, Governor Mills Signs Supplemental Budget Delivering Significant Financial Relief for Maine People Amid High Costs.

[57] See State of New Mexico’s Early Childhood Education and Care Department Press Releases from April 28, 2022, May 12, 2022, and May 24, 2022, Pew Charitable Trusts’ March 2024 article, What Happens When States No Longer Have Federal Pandemic Child Care Dollars?, and New Mexico State Investment Council’s Land Grant Permanent Fund webpage.