The next two-year State Budget will fund State-supported services in an uncertain financial and economic environment, with significant reductions in programs and services following substantial decreases in State revenue due to policy changes and national business conditions. Those national conditions include slower growth in corporate profits nationwide, which had accelerated substantially in the years following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. State policy choices have also substantially reduced revenue, particularly the elimination of the Interest and Dividends Tax in 2025 and the reductions in business tax rates from 2015 to 2023.[1]

Other key expenditures may impact the State’s fiscal stability in the next two years. The costs of delivering services generally increase over time with inflation. However, significant new costs associated with decades of alleged abuses of children in the State’s care at the former Youth Development Center and contracted agencies, any changes made to State obligations related to education funding currently being considered by the State Supreme Court, funding a new State prison for men, and any changes to federal funding that reduce resources available for the State of New Hampshire or its residents could impact both budget calculations and service needs.

The Governor’s State Budget proposal for State Fiscal Years (SFYs) 2026 and 2027 proposed appropriating about $16.0 billion to fund State operations and programs. Her proposal, which benefitted from relatively favorable revenue estimates, would have funded most agency operations near to levels in the current State Budget. The Govenror’s proposal included focused investments in a few key areas, such as specific public employee retirement costs and special education aid for school districts, and reductions in several others, including funding for the University System and in-home services for older adults and adults with physical disabilities.[2]

The House constructed its $15.5 billion budget based on lower revenues estimates than those in the Governor’s proposal. With the House Ways and Means Committee projecting revenues to the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund would be $513.5 million less under currrent policy across SFYs 2025-2027, the House made substantial adjustments to both raise more lottery and fee revenues and reduce expenditures, particularly in health and social services.

This report examines the State Budget proposal as approved by the New Hampshire House of Representatives on April 10, 2025. This report focuses on the changes between the Governor’s budget proposal and the House’s recommendations for the next two-year State Budget. It reviews topline figures associated with expenditures in the budget proposal, as well as expenditures and policy changes in each key policy area of the State Budget. This report examines proposed appropriations within each category of the State Budget, as well as for critical policy areas, such as housing and early care and education, that receive investments through the State Budget.[3]

Summary of Significant Changes Relative to the Governor’s Proposal

With about $513.5 million less combined revenue projected for the General and Education Trust Funds for SFYs 2025-2027, the House modified the Governor’s State Budget to reduce expenditures and increase revenue without changes to the State’s major taxes.[4]

The House primarily raised revenue through expanded gaming and increases in fees. Relative to the House Ways and Means Committee estimates for Lottery Commission revenues, the House’s final budget would raise $199.1 million in additional State dollars from gambling, including from revised revenue estimates, expanding video lottery terminals, and raising or modifying limitations on certain types of gambling. The House voted to either establish or increase 90 fees in statute, raising an additional $59.6 million in revenue during SFYs 2026 and 2027 combined, primarily through motor vehicle fees that would support Highway Fund revenues.[5]

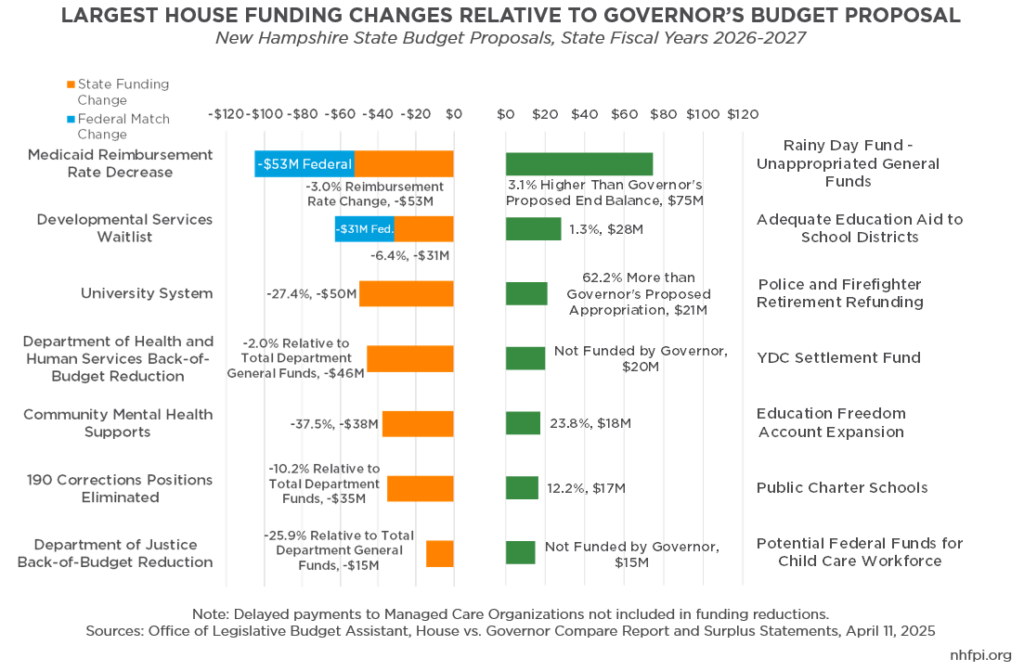

The House voted to significantly reduce appropriations relative to the Governor’s proposal in several key areas, including:

- reducing Medicaid reimbursement rates by three percent for all providers, lowering planned expenditures by $52.5 million in State General Funds and likely at least an equivalent amount in federal funds

- lowering funding for developmental services by $31.4 million in State General Funds, which likely also has an equivalent federal match of forgone funding, and would be expected to impact the ability to provide services to individuals aging into or needing enhanced services as well as those moving into the state

- dropping State Budget appropriations to the University System of New Hampshire by $50.0 million, or 27.4 percent, relative to the Governor’s proposal

- reducing funding for community mental health supports by $37.8 million, or 37.5 percent, relative to the Governor’s proposal, which had boosted funding by $12.0 million during the biennium primarily to support uncompensated care funding

- abolishing 326 filled and unfilled positions in State government (the equivalent of 1.6 percent of all Executive Branch positions reported June 30, 2024[6]), including eliminating 190 positions, and 149 filled positions, at the Department of Corrections

- eliminating four agencies entirely, including the elimination of the Human Rights Commission, the Office of the Child Advocate, the Housing Appeals Board, and the State Commission on Aging

- eliminating or defunding parts of other agencies, including the Division of the Arts within the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, the Family Planning Program, the Tobacco Prevention and Cessation Program, and the Prescription Drug Affordability Board

- requiring $95.5 million in back-of-the-budget reductions, including $46.0 million during the biennium at the Department of Health and Human Services and $14.7 million at the Department of Justice

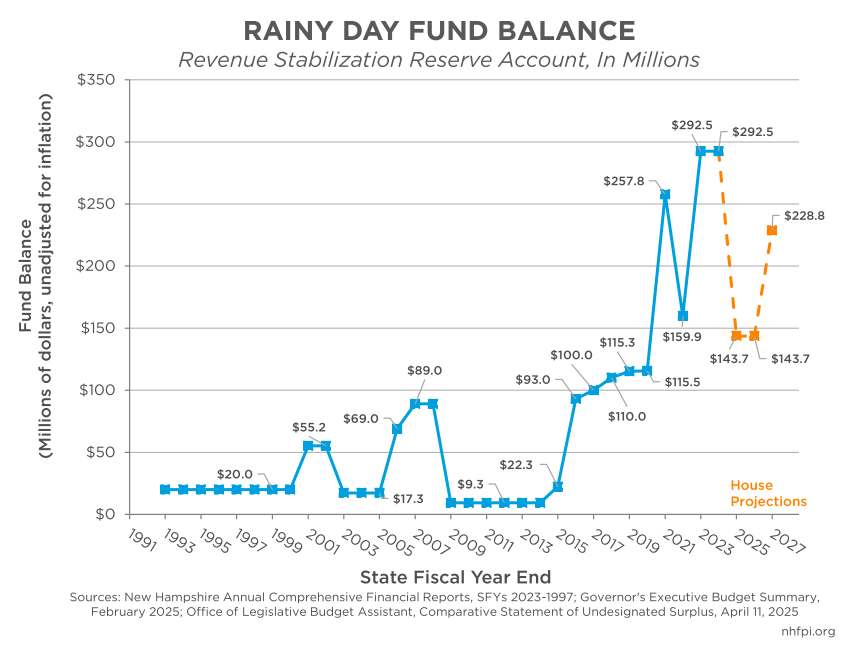

The House identified available funds to devote to other purposes and added funding in key areas. The House’s lower revenue estimates resulted in a projected draw from the State’s Rainy Day Fund of $148.8 million to erase the revenue shortfall at the end of the current State Budget on June 30, 2025. House policymakers prioritized replenishing the Rainy Day Fund, leaving a projected $85.1 million in unappropriated General Fund dollars to the Rainy Day Fund at the end of the biennium on June 30, 2027, while the Governor had proposed leaving $10.5 million unspent for the Rainy Day Fund. Beyond leaving those dollars unappropriated, the House voted to increase funding to:

- local public school districts by $28.1 million (1.3 percent relative to the Governor’s proposal), through boosting per pupil aid for students with special education needs and to school districts with lower taxable property values per student, while also capping certain forms of per pupil aid for school districts with the largest student populations in the state

- retirement benefits to certain public police and firefighting personnel who had their expected benefits changed after law changes in 2011, rising $21.1 million (62.2 percent) over the Governor’s appropriation for this purpose

- the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund, with a $20.0 million appropriation, as well as $10.0 million to fund the settlement of one court case related to past abuses at the Youth Development Center

- expand access to Education Freedom Accounts beyond the Governor’s expansion, devoting $17.5 million (23.8 percent more than the Governor’s proposal) to raising the income cap for all students, and then eliminating the income cap entirely in SFY 2027

- public charter schools, with $16.5 million (12.2 percent above Governor’s proposal) in additional resources

- federal funds to support the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program and the child care workforce

The House also attached significant policies to its version of the State Budget. In total, the House incorporated 34 separate bills into its proposal and added policies that had not previously existed in other pieces of legislation.[7] These policies included:

- open enrollment for public school districts, requiring that students be able to enroll in any school district in the state as long as that district has available space

- prohibiting diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings, initiatives, and policies, defined as being designed to achieve certain demographic outcomes, in State government, local governments, school districts, public higher education, and in contracts with these public entities, with the potential for school districts to lose State funding if they do not comply

- sunsetting the requirements for children to receive certain vaccines and modifying the authority of the State to require vaccinations

- permitting the end of a rental lease to be sufficient cause to evict a tenant in a rental property

- removing State inspection requirements for motor vehicles

- amending existing statute to identify that using biological sex to determine which restroom, locker room, or sports team an individual may participate in is not discriminatory under State law

- eliminating the solar component of the State’s Renewable Portfolio Standard and redefining the State’s energy policy to specifically encourage employing market forces and mechanisms to drive the use of energy resources

- legalizing certain weapons, including slung shots and metallic knuckles, and creating a new category of firearm that can only be manufactured and sold within New Hampshire to avoid regulation by the federal government

These funding and policy changes, as well as others, are detailed in the remainder of this Report.

The Topline Changes and Expenditure Differences by Category

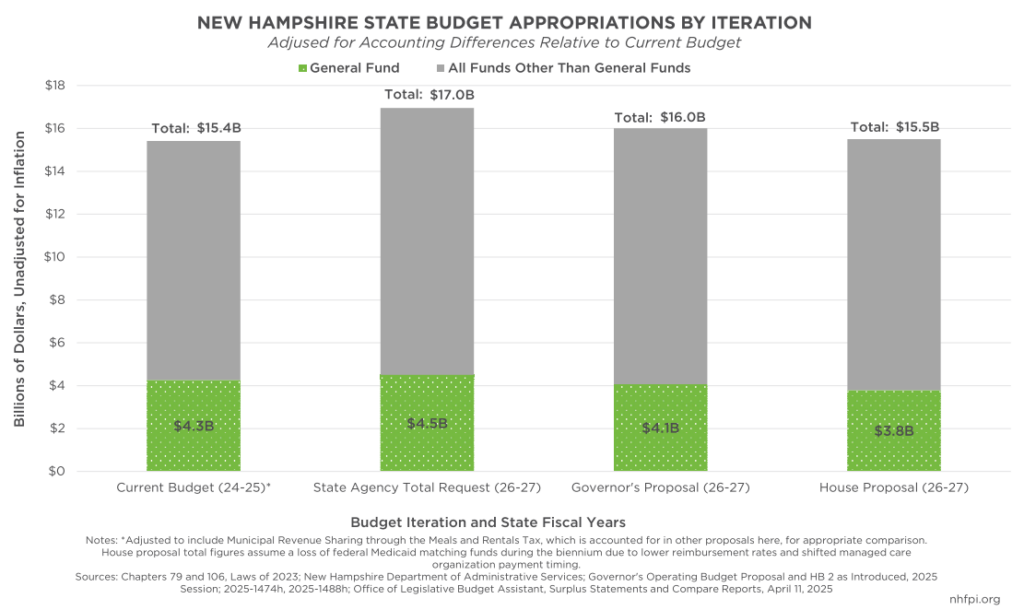

The House proposed reducing funding for services by about $509 million relative to the Governor’s proposal, bringing total State Budget funding proposed for the biennium down approximately 3.2 percent from the Governor’s proposed $16.0 billion budget to $15.5 billion. Adjusted for accounting differences but unadjusted for inflation, which averaged 2.9 percent annually for New England consumers in 2023 and 3.2 percent in 2024, the House’s proposed budget for the next two fiscal years is about $88 million (0.6 percent) larger than the current SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget.[8]

However, State General Fund appropriations would decline in the House’s proposal. General Fund dollars are a subset of the State Budget, and they are the most flexible dollars State policymakers have access to because they are solely from State revenue sources, rather than federal transfers or dedicated funds protected by law or the State Constitution.[9] General Fund dollars are about 28 percent of the current State Budget. If the House’s proposal were enacted, General Fund appropriations would be reduced; the House’s revenue estimates were lower than the Governor’s projections, and the House’s State Budget proposal relies on other funds to finance some services, while other services would be curtailed or eliminated. The House’s General Fund appropriations were about $275 million (6.8 percent) lower than the Governor’s proposed appropriations for the biennium, and about $476 million (11.2 percent) lower than the General Fund appropriations made for the current, SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget. Policymakers crafting the current State Budget had substantially more favorable growth rates in revenue projections for General Funds, including from revenues collected by the Interest and Dividends Tax, which generated $184.6 million in General Funds in SFY 2024, than current legislators have projected for next biennium.[10] The current State Budget funded both ongoing services and one-time projects with General Fund appropriations, and many of those appropriations were not repeated in the Governor’s or House’s budget proposals.

The funding changes include $95.5 million in back-of-the-budget reductions, which are requirements that State agencies reduce their expenditures without specifying which budget lines would be impacted. These back-of-budget reductions include $76.8 million in General Fund reductions.

At the end of the biennium, the House Finance Committee projects that the General Fund will have $85.1 million in otherwise uncommitted and unused dollars to transfer to the Rainy Day Fund.

Changes by Category

The State Budget divides all expenditures into six major categories, each representing a broad selection of departments and services. Shifts within these categories offer a general overview of changes in government spending. In order of funding size in the Governor’s proposed New Hampshire State Budget, the categories are: Health and Social Services, Education, Justice and Public Protection, Transportation, Resource Protection and Development, and General Government.

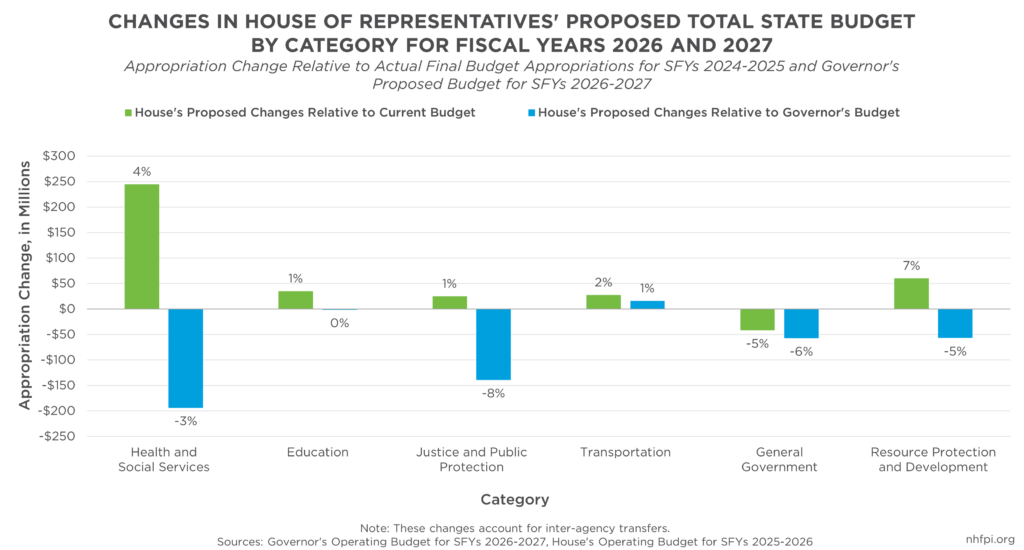

While the overall State Budget would increase under the House’s proposal compared to the current SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget as enacted, not all categories would experience equal changes. The Resource Protection and Development category would experience the largest percentage increase (7.2 percent, $60.3 million), while the Health and Social Services category would experience the second largest percentage increase (3.8 percent, $245.0 million). The categories of Education (0.9 percent, $35.2 million), Justice and Public Protection (1.3 percent, $25.1 million), and Transportation (1.7 percent, $27.5 million) would all experience increases below two percent, while the General Government category would be the only area to experience a decline (4.9 percent, $41.6 million).

Relative to the Governor’s proposed Budget for SFYs 2026-2027, all but one category, Transportation, experienced declines in the House’s proposal. The largest percentage declines would be in the categories of Justice and Public Protection (7.5 percent, $139.1 million) and Health and Social Services (2.7 percent, $193.6 million). The categories of General Government (6.4 percent, $57.2 million) and Resource Protection and Development (5.5 percent, $56.8 million) would experience similar declines, while funding for the Education category would drop slightly (-0.2 percent, -$1.3 million).

Health and Social Services

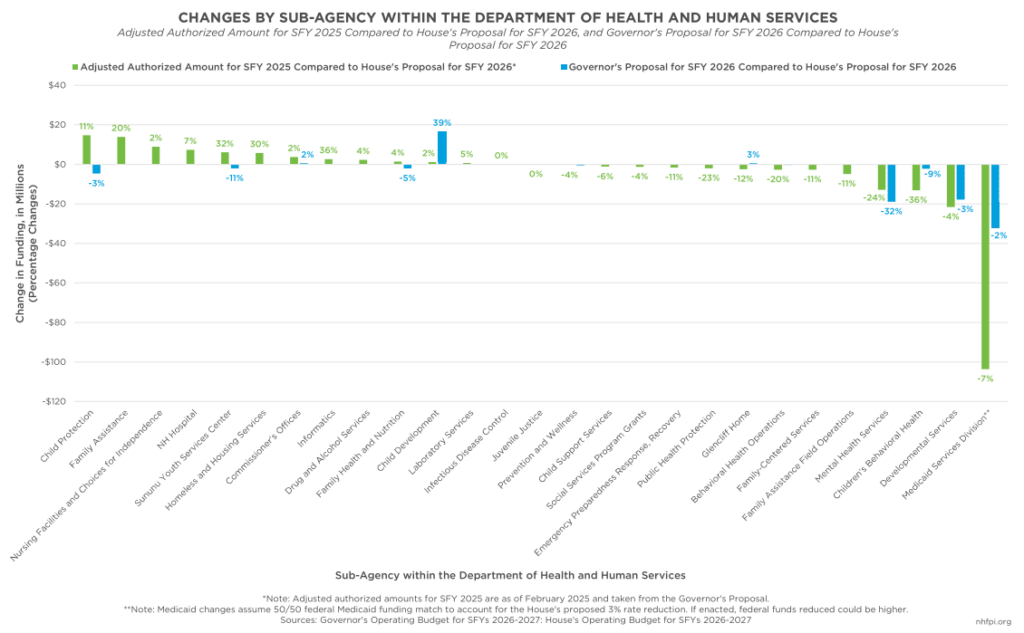

The Health and Social Services category of the State Budget is comprised almost entirely of the State Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which is responsible for several vital programs, including Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program (NHCCSP), child protection, public health services, and many others.

Under the House’s State Budget proposal, appropriations for the DHHS would decline by approximately $269 million (3.8 percent) from the Governor’s State Budget proposal, including federal funds likely to be forgone from key changes and added revenue from the sale of property at State facilities being used for health-related purposes. Reductions were proposed across several agencies and operations within the DHHS, including Medicaid, services for older adults and individuals with physical or developmental disabilities, community mental health supports, and public health initiatives, among other program areas.

Medicaid Services

The DHHS’s Division of Medicaid Services oversees the Medicaid program, which is a state-federal partnership that provides health coverage to those with low incomes and limited resources and helps ensure Granite Staters have access to health care services they may not otherwise be able to afford without coverage. As of the end of March 2025, 186,319 Granite Staters received coverage through the Medicaid program, and nearly half of enrollees (48.6 percent) were children. Around one third (32.0 percent) were enrolled in the Granite Advantage Health Care Program, which provides coverage to adults who are age 19 to 64 and have low incomes. The Medicaid program also serves other crucial populations, including children and adults with disabilities (8.4 percent of Medicaid population) and older adults (5.1 percent).[11]

The largest reduction proposed in the House’s State Budget was a three percent reimbursement rate reduction for all Medicaid providers in the state, reducing the amount of money that health providers receive for providing services. This provision would take effect January 1, 2026, reducing General Funds by $17.5 million in SFY 2026 and $35.0 million in SFY 2027. The DHHS would be required to collaborate with the Department of Administrative Services (DAS) to reduce the corresponding federal Medicaid match funds, also known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). The federal government covers at least 50 percent of all Medicaid costs in New Hampshire, and 90 percent of costs for the Granite Advantage Program, although potential federal policy and funding changes may impact the amount of money the state receives for Medicaid.[12]

The proposed rate reduction follows a three percent across-the-board Medicaid rate increase enacted during the current SFYs 2024-2025 biennium, which totaled $134.2 million in General Funds. The increase also included targeted higher rate increases for key services, such as community mental health and home and community-based supports. Increased allocations were intended to help ensure improved workforce retention and competitive wages among providers, as well as the expansion and maintenance of services that faced the potential of closure without such rate increases.[13]

The House’s State Budget also postponed the June 2027 Medicaid payments to Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) until the beginning of SFY 2028, effectively shifting the disbursement of funds until the next biennium. While this adjustment is not expected to affect service delivery, it would delay the timing of payments outside the current budget cycle and assumes greater availability of funds during the next biennium. This provision would save $25 million in General Funds during SFY 2027, in addition to likely equivalent federal Medicaid matching dollars, impacting MCO payments for the Granite Advantage Program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and standard Medicaid.

Changes in funding policies for the Granite Advantage Program, including the repeal of the annual automatic 5 percent transfer from the Liquor Fund into the Granite Advantage Healthcare Trust Fund, were included in the House’s proposal. The provisions would prohibit the automatic transfer from the Liquor Fund in the event of any funding shortfalls and allow the use of General Funds for the program, which is prohibited under current law.

The Granite Advantage Program is funded outside of the State Budget; however, the House’s proposal allocates additional money to help prevent shortfalls during the biennium, appropriating State Budget funds to this program for the first time since Medicaid Expansion was first adopted by New Hampshire in 2014.[14] General Fund allocations total $12.6 million in SFY 2026 and $1.0 million in SFY 2027, a decline in the second year from the projected $13.0 million before accounting for revenues collected through enrollee cost shares proposed in the Governor’s State Budget and retained by the House. Under the proposals, Granite Advantage adults at or between 100 to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) would be required to pay premiums for their health care coverage, resulting in $12.0 million in collected revenue in SFY 2027 alone; this would offset General Fund appropriations for the program in SFY 2027. The House also retained other cost shares proposed by the Governor, including premiums for CHIP enrollees at or above 255 percent of the FPL, as well as higher prescription cost shares, which would increase from $1-2 to $4.[15]

In addition to larger funding changes and reductions within the DHHS’s Division of Medicaid Services, the House’s State Budget proposal included several other smaller adjustments, including:

- establishment of a research study on the Adult Dental Program to determine cost-effectiveness, with the DHHS required to submit a report to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee by January 1, 2027

- creation of an incentive program among MCOs to encourage Medicaid recipients to seek the lowest cost outpatient procedures when appropriate, with the DHHS required to establish an implementation plan within 30 days of passage

- termination of the Medicaid to Schools Program if current parental consent policies are ever changed at the federal, state, or local level

- addition of three staff members for Medicaid Recoveries, bringing in a net General Fund savings of approximately $271,000 in SFY 2026 and $534,000 in SFY 2027 when accounting for additional estimated recoveries resulting from increased staff[16]

- accelerated implementation of the at-home dialysis program for Medicaid recipients, saving an estimated $50,000 in General Funds for SFY 2027 alone

- allowance of standing orders for certain over-the-counter medications, medical supplies, and lab tests covered under Medicaid

Developmental and Aquired Brain Disorder Services

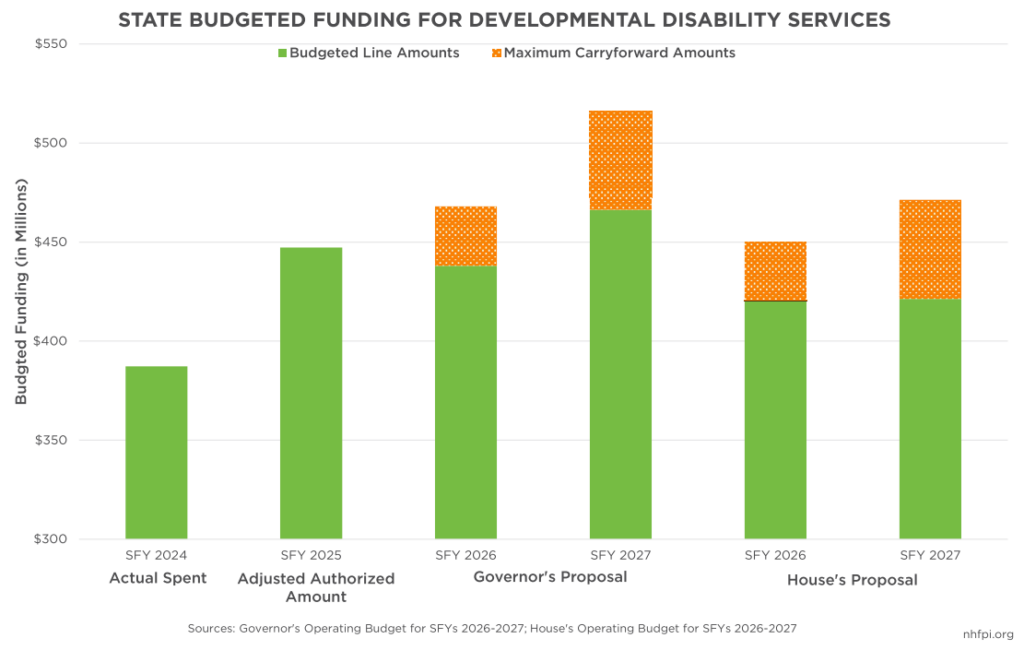

Under the House’s proposal, funding for developmental disability services was reduced relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, equating to a General Fund reduction of $8.9 million in SFY 2026 and $22.5 million in SFY 2027. When accounting for the federal Medicaid match rate, the equivalent amount of Federal Funds would be reduced, totaling $62.8 million across the biennium in both General and Federal Funds, which is the second largest reduction for service funding lines proposed in the House’s State Budget. Policymakers stated expectations that the decline in funding would primarily impact the developmental disability waitlist for services, including children aging out of school-based services and people with disabilities who move into New Hampshire; however, the reduction could also impact anyone currently receiving services who may need enhanced or additional assistance during the upcoming biennium. According to the DHHS, 278 people are expected to need services during the SFYs 2026-2027 biennium.[17]

While funding has been reduced, the House has retained two unique organizational footnotes included in the Governor’s proposal that may help ensure that the DHHS is able to meet its legal obligation to provide services for those with developmental disabilities. The first allows the DHHS to request additional funds through the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee in the event that spending exceeds the budgeted amount. The second note directs the DHHS to use funds carried forward but unused from prior appropriations of up to $30 million in SFY 2026 and $50 million in SFY 2027, drawing on the Developmental Services, Acquired Brain Disorder Services, and In-Home Support Waiver Funds.

Older Adults and Adults With Physical Disabilities

Counties are responsible for contributing a portion of funding for long-term care services provided through Medicaid for their residents, including care in nursing facilities and home- and community-based services. Under current law, the annual growth in the required county contribution is capped at 2 percent. However, the House’s State Budget proposed raising this cap to 3 percent for the next biennium only. With this change, counties would be required to contribute more funds towards the total cost of care, boosting the cap up to a statewide maximum of $135.8 million in SFY 2026 and $139.9 million in SFY 2027. This year-over-year increase follows the stagnation of county contributions in the current State Budget, with counties required to contribute equal amounts in SFYs 2024 and 2025 ($131.8 million).

Under the House’s proposal, counties would receive compensation for overpayments towards their share of Medicaid costs in SFYs 2020-2021. Approximately $5.6 million would be allocated annually among the counties for SFYs 2026-2029, equating to nearly $11.3 million across the upcoming biennium. While the proposed increased caps would typically put more fiscal pressure on counties, these reimbursements would be larger than contribution increases and may help offset cost constraints during this biennium.

While overall funding for long-term care remained the same between the Governor’s and House’s proposals, funding for the state’s Choices for Independence (CFI) Program declined by $16.5 million (11.6 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the proposed amount for SFY 2026. Medicaid funding for nursing facilities would increase by $57.4 million (23.4 percent) between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the proposed amount for SFY 2026 in both the Governor’s budget and the House proposal.

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services

A significant funding reduction was proposed for community mental health supports, with the House budgeting $37.8 million less in General funds for the biennium, 37.5 percent lower than what the Governor initially proposed. The Governor’s Budget proposed approximately $50.4 million each year of the upcoming biennium towards housing supports for those served through the community mental health system (38.4 percent); rapid response services, including funding for 988 and other suicide prevention (29.8 percent); community mental health centers, including uncompensated care (18.2 percent); transitions in care, such as transitional housing (12.3 percent); and operations (1.3 percent).[18] Under the House’s State Budget, funding for community mental health would remain flat at $31.5 million each year, a significant decline from the $44.4 million in Adjusted Authorized funds for SFY 2025.

Funding reductions among community mental health services would primarily affect non-Medicaid contracts and services within the community mental health system, as well as remove a proposed $10 million biennial increase for uncompensated care that was included in the Governor’s State Budget. According to testimony from the DHHS to the House Finance Committee, the Department anticipates elevated spending this fiscal year due to increased support for the Mission Zero Initiative, which seeks to eliminate psychiatric boarding in hospital emergency rooms and decrease wait-times for accessing services.[19] Approximately 30,366 people were served through the community mental health system in SFY 2024, including 9,459 people who received services through mobile crisis units.[20]

The House’s State Budget also proposed the sale of various state-owned properties used or formerly used to house individuals experiencing mental health concerns or housing instability. The proposed sale of the Philbrook Center would bring in an estimated $5.0 million in SFY 2027, with the Center currently being used as transitional housing for 16 people who were formerly receiving services at NH Hospital. The Tirrell House, which is currently used as a shelter for people experiencing homelessness in Manchester, would be sold for an estimated $300,000 in SFY 2026. Finally, unoccupied State-owned properties at Hampstead Hospital would be sold, although no estimated savings were proposed; portions being used as a replacement facility for the Sununu Youth Services Center (SYSC) would not be included in the sale. All properties would be first offered to the city or town in which they reside, then to each corresponding County, before being placed on the open sale market by January 1, 2026.

In addition, under the House’s State Budget, the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund would be supplied with allocations from the Opioid Abatement Trust Fund for the upcoming biennium only, backfilling the proposed repeal of the annual five percent transfer from the Liquor Fund. Available Liquor Funds would be distributed back into the General Fund, equating to $10.7 million each fiscal year. In order to help ensure that funds will be available, the House also proposed the termination of all contracts, grants, or other agreements funded with Opioid Abatement Funds with effective dates on or after May 1, 2025.

The House also extended lapsing funds for the Recovery Friendly Workplace Initiative, with approximately $2.1 million allocated in the current State Budget. The Governor’s Budget proposed $1 million in additional funds for the Initiative, which the House has retained.

Finally, the House’s State Budget allocated $486,000 in General Funds each year of the biennium for funding certain staff positions at Glencliff Hospital that were not included in the Governor’s proposal. The House Finance Committee reduced all allocated funds for the Prescription Drug Affordability Board to fund part of these positions, although the Board was not eliminated in its entirety.

Sununu Youth Services Center

Funding for the SYSC was reduced by $2.0 million in SFY 2026 and $3.0 million in SFY 2027 relative to the Governor’s proposal. Reductions follow a $6.1 million (47.8 percent) increase between the Adjusted Authorized amount for SFY 2025 and the Governor’s proposal for SFY 2026.

The House’s State Budget also allows for the use of General Funds to support construction and infrastructure development at the SYSC replacement facility, although no funds were allocated for that purpose. Under current law, only federal funds could be used for this purpose.

Youth and Family Services

The House’s State Budget proposed a 10 percent across-the-board reduction for residential placements relative to the Governor’s proposal, including those funded through both the Child Protection Services and through the Division of Behavioral Health’s System of Care. These General Fund reductions would equate to $5.1 million in SFY 2026 and $5.7 million in SFY 2027.[21]

The House also proposed a mandate to require the DHHS to seek and utilize the maximum amount of available Title IV-E federal funds. The DHHS would be required to report on its efforts biannually to the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee.

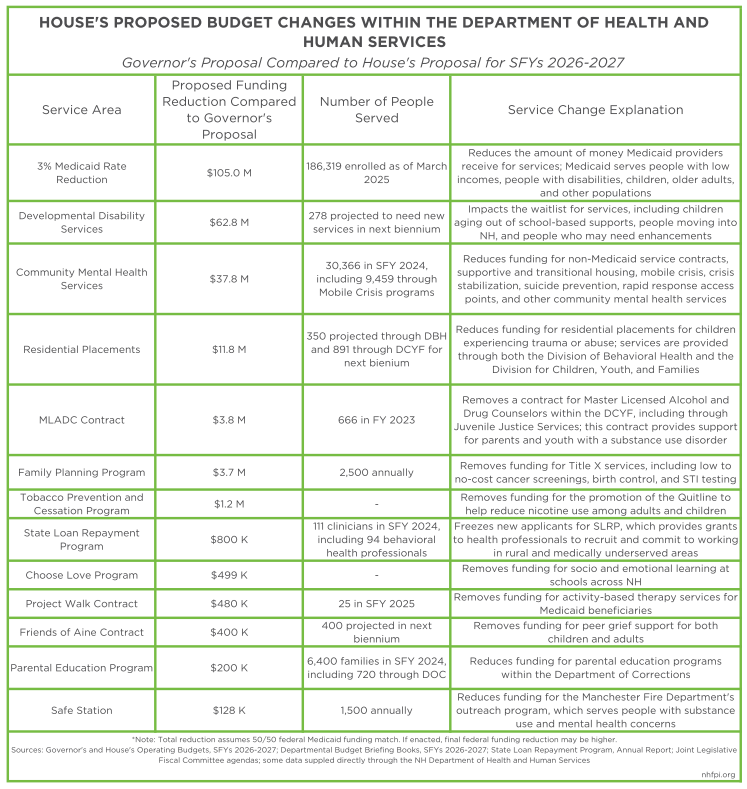

Eliminations and Reductions of Other Services

The House’s State Budget proposed eliminating or reducing funds for several smaller programs that provide essential services for Granite Staters. When combined, the eliminations and reductions listed below total $9.8 million in General Fund savings across the biennium, or 0.004 percent of the General Funds proposed by the Governor’s State Budget proposal for the DHHS.

Proposed eliminations among the DHHS include:

- Family Planning Program ($3.7 million total savings, including $1.7 million in General Funds): This program currently funds Title X services providing low to no-cost preventative reproductive health care, including cancer screenings, birth control access, and STI testing. Services are offered at health centers across the state and serve approximately 2,500 people annually, according to the DHHS.[22]

- Tobacco Prevention and Cessation Program ($1.2 million General Fund savings): These allocations are used to fund contracts for the promotion of the State’s Quitline, providing services for both adults and youth seeking to reduce nicotine use. While the proposed elimination of General Funds would not impact federal funds, future funds may be reduced due to separate funding changes at the federal level, according to DHHS testimony to the House Finance Committee; $2.3 million in federal funds were proposed for SFYs 2026-2027.[23]

- MLADC Program ($3.8 million General Fund savings): This contract within the Division for Children, Youth, and Families supplies funding for services provided by Master Licensed Alcohol and Drug Counselors (MLADC). According to the DHHS, 999 referrals were made and 666 families were served through the program in SFY 2023, with approximately 14 contracted staff making up the program.[24]

- Friends of Aine ($400,000 General Fund savings): This contract currently funds peer-to-peer grief support and services. According to the DHHS, approximately 400 people are expected to be served in the upcoming SFYs 2026-2027 biennium.[25]

- Choose Love Program ($499,959 General Fund savings): This program currently provides social and emotional learning in schools across the state, and was included as one of the identified strategies in the Governor’s Task Force on School Safety Preparedness[26]

- Project Walk ($480,000 General Fund savings): This contract provides activity-based physical therapy services for Medicaid beneficiaries, with approximately 25 people served in SFY 2025, according to the DHHS.[27]

While the program was not eliminated in its entirety, the WIC Farmers’ Market Program was suspended until funds are available, removing the non-lapsing provision currently in place and making an estimated $560,000 in General Funds available for other uses during the upcoming biennium.

In addition to proposed eliminations, smaller reductions across the DHHS include:

- State Loan Repayment Program ($800,000 General Fund savings): This program would not accept new applicants during the biennium, although funding would continue for current recipients. The SLRP provides assistance with student loans to help recruit and retain health professionals to commit to working in rural and medically underserved areas in the state. According to the DHHS, 111 providers were participating in the SLRP during SFY 2024, with 94 being mental health clinicians.[28]

- Parental Education Program ($200,000 General Fund savings): This contract currently supports funding for parental education programs at 16 Family Resource Centers across the state, with reductions proposed for the state’s Department of Corrections’ portion of the program. Approximately 6,400 families received support in SFY 2024, including 720 through the DOC, according to the DHHS.[29]

- Manchester Fire Department Safe Station ($128,000 General Fund savings): This contract provides funding for outreach programming to people in need of substance use and mental health treatment, with approximately 1,500 people reached annually.[30]

Other Proposed Changes Impacting Health and Social Services

In addition to fiscal changes, the House’s State Budget proposal included the text of several other bills already passed separately by the House.[31] These included:

- House Bill 73, which defines harm reduction and establishes a substance use disorder access point program, although no funds were allocated for the program[32]

- House Bill 94, which prohibits the use of Medicaid funds for elective circumcision procedures, equating to an estimated General Fund savings of $75,000 across the biennium

- House Bill 117, which makes policy changes regarding pharmacist discretion and the substitution of biological products, such as vaccines or certain medications

- House Bill 223, which exempts certain health care facilities, such as emergency medical, walk-in, and other special care centers, from certain procedural and licensing requirements for new facilities if those centers are located within 15 miles of a critical access hospital[33]

- House Bill 357, which terminates regulations requiring children to receive immunizations for varicella, Hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), as well as modifies a provision within statute that provides the State with authority to establish vaccination requirements for children through rulemaking[34]

The House also adopted an amendment that permits the addition of more nursing facility capacity, rehabilitation hospitals, or other similar facilities for membership-based models or for people who provide direct payment for services, as well as allows these membership or direct-payment facilities to not provide services to all people who require services regardless of their source of payment.[35]

The House’s State Budget also changes the name of the Office of Health Equity to the Office of Health Access, as well as keeps a hiring freeze in place for the Office throughout the end of the next biennium, even if the Governor’s current hiring freeze is lifted. According to information provided to the House Finance Committee, this would impact four positions within the Office that are currently vacant.

Language in the House’s State Budget would also require the DHHS and contractors to comply with the State’s Patient Bill of Rights, with the DHHS permitted to not contract with or pay vendors who fail to comply with the order.

Among other changes, the House also proposed $693,000 across the biennium for funding a DocuSign system within the DHHS. The House also reduced a contract with the University of New Hampshire’s Epidemiology Program by half, saving $18,200 each year of the biennium. Under the House’s budget proposal, the State would permit therapeutic cannabis “alternative treatment centers” to be operated as for-profit entities; law currently limits the operations of these facilities to non-profit organizations. Finally, the proposal also allows the DHHS to accept up to $250,000 in gifts and donations, up from the $1,000 proposed in the Governor’s Budget.

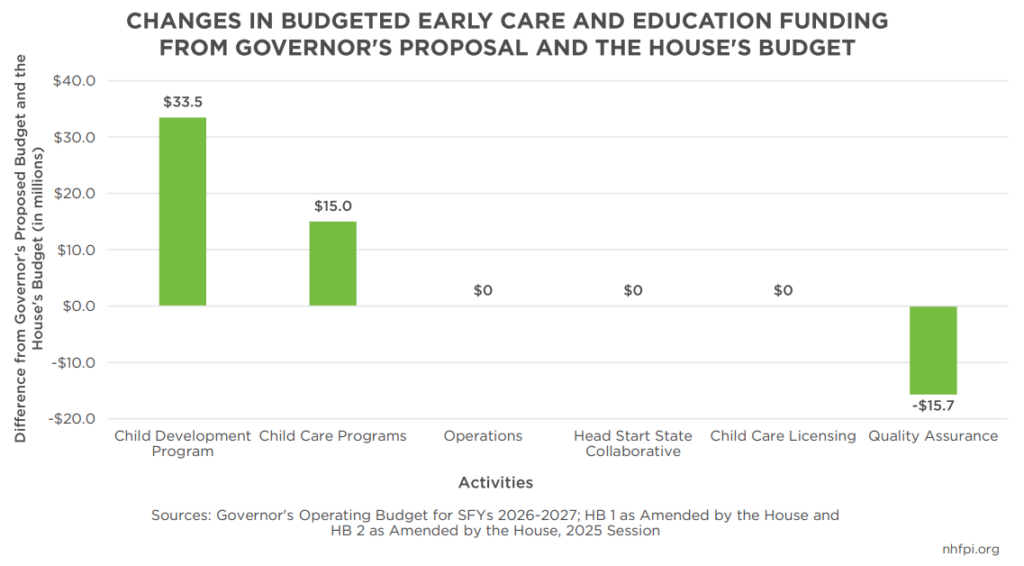

Early Care and Education

The House’s budget increases overall expenditures for early childhood care and education (ECE) by approximately $32.8 million from the Governor’s proposed budget over the biennium. The increased funding is due entirely to changes to proposed uses of federal funds made by the House. The Child Development Program and the Child Care Programs activities received increased funding. Child Development Operations, the Head Start State Collaborative, and Child Care Licensing funding were unchanged, and the Quality Assurance activity was reduced.

The largest increase of approximately $33.5 million over the biennium is allocated for the Child Development Program activity. The majority of this increase is in the “Employment Related Child Care” line, which funds the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship Program (NHCCSP), a state-federal partnership that provides funding assistance for child care expenses to families with low and moderate incomes. NHCCSP eligibility was expanded to include children in households earning no more than the 85th percentile of state median income as part of the current State Budget and was first implemented in January 2024. In the first year of expanded eligibility, NHCCSP utilization increased by 46 percent, from 2,660 children in December 2023 to 3,884 in December 2024. As of February 2025, there were 4,103 children using Child Care Scholarships, the highest rate of usage since approximately SFY 2020 and a 54 percent increase since the eligibility expansion.[36]

The House’s budget allocates nearly $90.0 million in the SFYs 2026-2027 biennium budget proposal to the Child Development Program, including funding for NHCCSP. This allocation comprises approximately 0.6 percent of the House’s proposed $15.5 billion State Budget for SFYs 2026-2027. Using the DHHS Division of Economic Stability’s projected average cost per child in the NHCCSP for SFYs 2026-2027 ($8,874, approximately $630 less per child than actual costs from SFY 2024 and over $2,800 less than per child adjusted authorized amount for SFY 2025), the proposed allocations would allow approximately 5,054 children to utilize NHCCSP funding in SFY 2026 before a waitlist would be enacted for the program. As many as 55,000 children under 13 years old may be eligible for the NHCCSP, or approximately 32 percent of all children under 13 in New Hampshire in 2023, the most recently available data from the U.S. Census Bureau.[37] Based on these estimates, the current proposed allocations would only cover 9.2 percent of all potentially eligible children in the state.

Should a NHCCSP waitlist develop, language in the House’s version of the Trailer Bill authorizes the DHHS Commissioner to request additional funding for the program with approval from the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee and the Executive Council. Additionally, under federal rules and regulations, states can utilize up to 30 percent of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) reserve funding for child care assistance if NHCCSP funds are depleted and additional families are eligible for the program. At the end of SFY 2024, New Hampshire had a TANF reserves balance of approximately $74.5 million dollars.[38] If 30 percent of TANF reserves available at the end of SFY 2024 were transferred to the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF; the state-federal fund from which child care assistance is drawn), there would be an additional $22.3 million available for the program. The TANF reserve balance, however, would not be a sustainable form of funding for an extended period if the state’s funds are consistently drawn down to supplement CCDF funding.

The House’s budget decreases funding for the Child Care Quality Assurance activity by approximately $15.7 million compared to the Governor’s proposed budget, nearly all of which affects funding for “Grants for Public Assistance and Relief.” Funding in this line supports contracts for quality initiatives, including ECE workforce professional development, web-based health and safety training, the 2027 market rate survey, the child care resource and referral program, and the NH Connections data management system. This reduction funds the Quality Assurance activity at approximately $5.8 million annually for SFYs 2026-2027, which is nearly $2 million more than what was spent in SFY2024 but about $1.2 million less than the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized amount.

The House’s budget also reinstates $15 million dollars for Child Care Workforce Grants that were funded using General Funds during the current budget cycle. This initiative disseminated funds to ECE providers who could use the grants for a variety of recruitment and retention efforts for their staff. The House inserted a footnote in the budget directing this allocation come from TANF reserve funding. While TANF reserve funding can be converted to CCDF funding, the funds must function as CCDF dollars after the conversion.

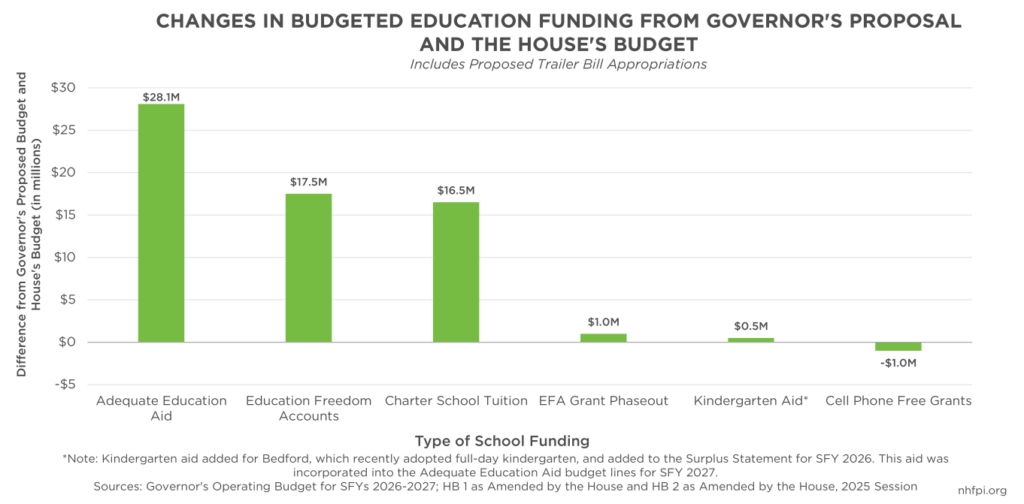

Education

The House’s budget, relative to the Governor’s proposed budget and funding in the current State Budget, includes increases for K-12 education but decreases allocations for the Community College System of New Hampshire (CCSNH) and the University System of New Hampshire (USNH). Changes in K-12 education funding reflect increases in Adequate Education Aid to local public schools, Education Freedom Account (EFA) funding, and charter school tuition, as well as several smaller funding changes.

The House’s budget also recommended several policy changes to the Department of Education and the Education Trust Fund that may help address State revenue shortfalls, create more flexible funds for non-education expenses, and require all public K-12 and higher education institutions to eliminate contracts and remove programs related to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

K-12 EDUCATION

The House’s budget increases Adequate Education Grants and per student differentiated aid, which are distributed through the State’s education funding formula, for SFY 2027 relative to current policy. The changes would increase the grant amounts by 2 percent annually, which is consistent with current policy, but would keep those amounts rounded up to the next whole dollar. While most of these changes are relatively small in terms of the aid distributed, funding for each student receiving special education services would be increased substantially in these changes.

With the amounts re-specified in law, rather than based on the old formula, the base per student grant would be $4,351, a very slight boost from the $4,350.95 that would have been distributed in SFY 2027 under prior policy. The following increases for each student qualifying for differential aid are incremental, rounding up to the nearest whole dollar, with the exception of the much more significant boost for Special Education Differentiated Aid:

- $2,441 for students eligible for free or reduced price meals

- $849 for students who are English language learners

- $3,140 for students receiving special education services, a boost of about $911 per student relative to the current policy’s 2 percent annual increase

Compared to the Governor’s budget, the House’s budget increases State Adequate Education Grants by $28.1 million ($2.19 billion total, including $546.9 million of “restricted revenue” from the Lottery Commission), EFA funding by $17.5 million ($91.0 million total), and funding for public charter schools by $16.5 million ($151.5 million total). The House also adopted language from the Governor’s proposed budget requiring school districts to develop policies for cell phone-free classrooms but removed the $1.0 million allocation to help school districts implement programs.

Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid, which was repealed as part of the education funding formula adjustments enacted through the current State Budget, would be returned under the House’s budget proposal. This aid would go to municipalities that have relatively low taxable property values per student and would total up to $1,250 per student. There would be a sliding scale reduction for this aid that disappears for municipalities with more than $1.6 million in taxable property value per pupil. This aid would be added to the existing Extraordinary Needs Grants in the education funding formula, which are based on both relative property values and the number of students eligible for free and reduced-price meals; however, the House budget caps aid for the largest communities in the state. In municipalities with more than 5,000 resident students, the total amount of Extraordinary Needs Grants and Fiscal Capacity Disparity Aid combined would be limited to $3,750 per student. Currently, only the cities of Nashua and Manchester exceed 5,000 resident students.

The House voted to expand EFA income-based eligibility to 400 percent of the federal poverty guidelines ($106,600 for a family of three and $128,600 for a family of four in 2025) for Academic Year 2025-2026. The program would be expanded to universal eligibility after June 30, 2026. The House also increased funding by $975,000 compared to the Governor’s proposal for EFA Phase Out Grants, a program that provides partially funded adequacy grants to public K-12 schools for each student who previously attended a public school and enrolls in the EFA program.

The House, acknowledging the separate, independent passage of House Bill 739, estimated a $27 million increase in revenue in SFY 2027 from eliminating the local retention of Statewide Education Property Tax (SWEPT) funds. Currently, when communities raise more revenue than they need to pay for the State’s Adequate Education Aid requirements through SWEPT, they keep the excess funds for other local education uses. Under the proposed language, these communities would have to provide payment of these “excess” amounts to the State. While the House did not incorporate the separate bill into the State Budget, it assumed revenue would be collected from its potential future enactment.

Open public school enrollment was recommended as part of the House’s budget package, which would permit parents to enroll their children in any public school in the state, provided the school has space to accommodate additional students outside of the district. School districts would have to maintain public lists of available openings.

Additionally, on the recommendation of the Department of Education, the House removed 37 unneeded, vacant, or temporary positions from the budget, saving about $7.3 million over the biennium. These positions included an early childhood coordinator, an early childhood content expert, a school nurse coordinator, and a computer science administrator that all would have been funded through the General Fund.

The House passed an amendment that would ensure schools receive at least 80 percent reimbursement for Special Education Aid if funding runs out at the state level. Policymakers expressed hope that schools will be funded at 100 percent of their reimbursements based on the increased funding in the budget proposed by the Governor, as the House did not reduce Special Education Aid appropriations relative to the Governor’s proposal.

Several appropriations currently funded through the Education Trust Fund are recommended to be funded through the General Fund by the House, including:

- Special Education Aid

- Tuition and Transportation

- School Building Aid

- Court Order Placements

- DHHS Division of Children, Youth, and Families Court Placements

- State Testing

- Building Lease Aid

- Public School Infrastructure Fund

If the changes become law, the Education Trust Fund will house funding for aid for full-day kindergarten, EFA phase out grants, charter school funding, funding for the Low and Moderate Income Homeowners Property Tax Relief program, EFAs, State Adequate Education Aid, and the Department of Education’s Education Trust Fund administration. Shifting more revenues and expenditures away from the Education Trust Fund to the General Fund would provide policymakers with additional flexibility to shift appropriations, as the General Fund does not have restrictions on its use. However, the House’s budget would also shift lottery revenues to a special restricted account to ensure those dollars are not used on EFAs and help maintain compliance with the State Constitution.[39]

To generate additional flexibility for available funding, the House approved lowering the percentage of revenues collected by the Business Profits Tax, Business Enterprise Tax, Real Estate Transfer Tax, and Tobacco Tax allocated to the Education Trust Fund to 30 percent. While the split between the Education Trust Fund and the General Fund varies among these four tax revenue sources currently, a higher percentage of each flow to the Education Trust Fund, rather than the General Fund, under current law.

A budget cap for local school districts included in the House Fiscal Committee’s State Budget recommendation was not adopted by the House. The cap would have limited school budget increases to no higher than a set amount determined by the Northeast Region Consumer Price Index prior to June 30, 2027. After that date, appropriations would have been limited to the five-year average percent change in the number of students, or the five-year average of past appropriations.

Public Higher Education

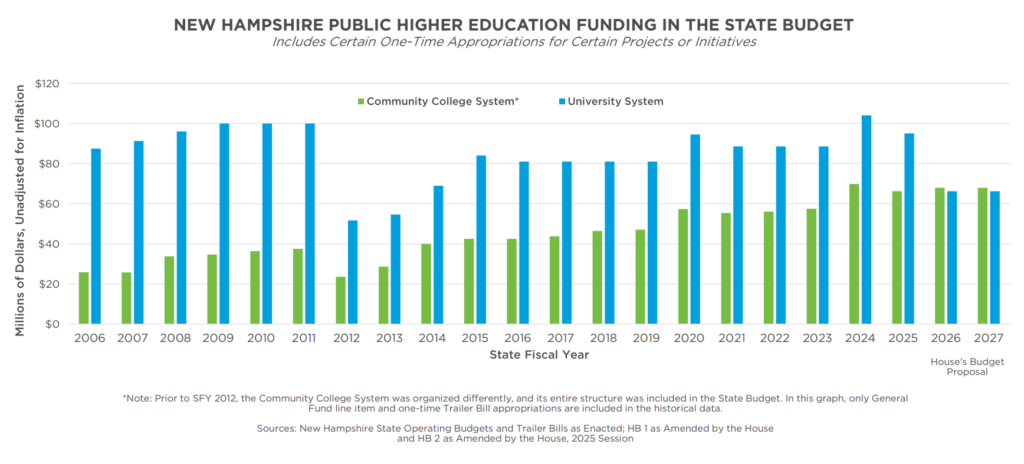

Under the House’s budget, funding for the Community College System of New Hampshire (CCSNH) would be reduced by approximately $4.1 million over the biennium compared to the Governor’s proposed budget, a level of funding similar to the current State Budget. The House approved an earmark of $2.5 million each fiscal year for the dual and concurrent enrollment program, which allows high school students to take college credits for free through CCSNH, and $200,000 each year for the math learning communities, a program that offers higher-level math courses to high school students to prepare them for their post-secondary goals.

The University System of New Hampshire (USNH) would have a reduction of $50 million over the biennium relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, which would total a 33 percent decrease in state appropriations from the current biennium funding levels. The General Fund decrease for the USNH totals $80 million over the biennium but is offset partially by the proposed use of UNIQUE funds associated with 529 accounts to add $30 million to the University System appropriation during the biennium.

Prohibition of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

The House’s Trailer Bill includes language that, if passed by the Senate, would prohibit “…diversity, equity, and inclusion [DEI] in public schools,” including K-12 schools, academic institutions, and institutions of higher education. DEI is defined in the proposed language as “…any program, policy, training, or initiative that classifies individuals based on race, sex, ethnicity, or other group characteristics for the purpose of achieving demographic outcomes, rather than treating individuals equally under the law.”

If adopted by the Senate, public schools will need to review all existing contracts for “DEI-related provisions” and provide a summary report to the commissioner of the Department of Education of any contract with DEI-related provisions, along with “contract descriptions, the specific DEI-related provisions, and the total financial obligation associated with each contract.” Schools that do not complete the process will lose all public funding until they achieve compliance with the policy.

Outside of education specifically, this amendment would require that all State Executive Branch agencies and all cities, towns, and counties not implement DEI-related initiatives or activities, including trainings, policies, and hiring or contracting preferences. State and local governments could not renew or enter into any new contract that includes DEI-related provisions, and State agencies would be required to review all contracts for DEI-related provisions by October 2025.

Housing

While housing initiatives and supports comprise a relatively small portion of the overall State Budget, the House proposed several changes that would alter those proposed by the Governor. The House’s State Budget removed the extension of funds for the Housing Champion Designation and Grant Program, which was established in the current SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget and incentivizes municipalities to encourage zoning and other infrastructure changes. While new funds were not added, the House proposed the establishment of the Partners-in-Housing Program, introduced through House Bill 572, to promote the construction of affordable and workforce housing, although no funds were allocated for the program.

The House also proposed adding language from House Bill 60 that would allow for “no cause” evictions, stating that the end of a lease period is sufficient grounds for the eviction of tenants.[40]

Although there were changes in other housing initiatives, funding for the DHHS’s Bureau of Homeless Services remained unchanged between the Governor’s and House’s proposals. This included an increase of $10 million across the biennium in Opioid Abatement Funds to support those experiencing homelessness, as well as the maintenance of increased rates paid to shelters which was enacted in the current SFYs 2024-2025 Budget. The House also added a unique footnote to the Bureau of Homeless Services’ budget line that would ensure that $500,000 is reserved for Waypoint Youth Homeless Shelter.

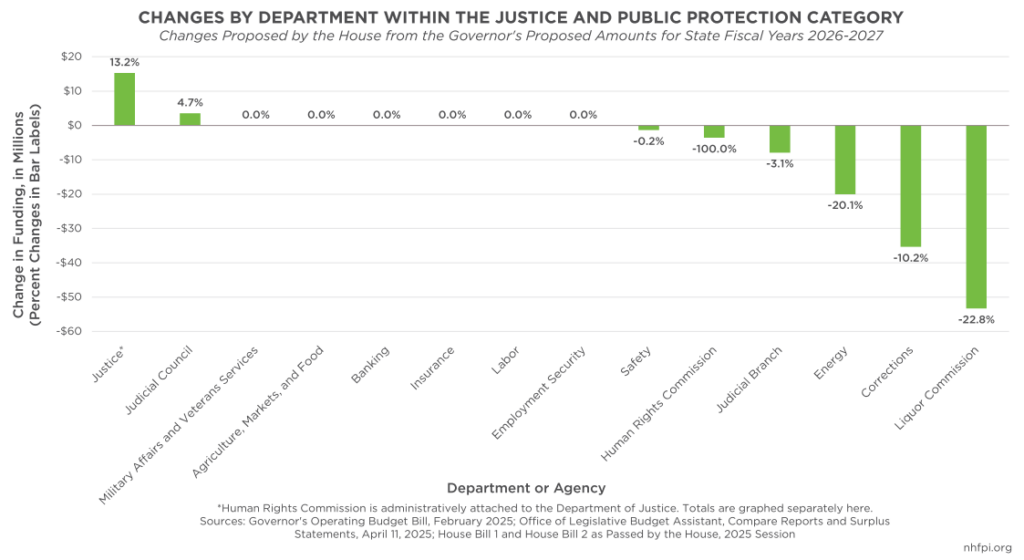

Justice and Public Protection

Key agencies within the Justice and Public Protection category of the State Budget include the judicial branch of State government, the Departments of Justice, Insurance, Safety, Banking, Military Affairs and Veterans Services, Energy, Labor, Corrections, Employment Security, and Agriculture, Markets, and Food. The Liquor Commission, Human Rights Commission, Judicial Council, and several other boards and offices are also within this category.

Relative to the Governor’s budget proposal, the most significant funding changes proposed by the House were the result of shifts in funding structures for operations and the elimination of positions, particularly at the Department of Corrections (DOC). There were also changes to policy initiatives and the elimination or consolidation of several agencies.

Department of Corrections Positions

Funding for the DOC would decline by $35.4 million (10.2 percent) relative to the Governor’s budget proposal under the House’s budget. The SFY 2024 expenditure for the DOC was $175.0 million, and the SFY 2025 Adjusted Authorized current budget is $177.3 million. Under the House’s State Budget proposal, appropriations would drop to $153.1 million in SFY 2026 and $156.7 million in SFY 2027.

This cost reduction would be achieved by eliminating positions. The House’s proposed State Budget would abolish 190 positions at the DOC, including 149 positions that were not listed as vacant.[41] These positions include:

- 36 at the State Prison for Men, including 15 filled positions

- 14 at the Northern New Hampshire Correctional Facility in Berlin, including four filled positions

- 7 at the New Hampshire Correctional Facility for Women, including one filled position

- 5 at the Secure Psychiatric Unit, including two filled positions

- 9 funded for mental health services, none of which are indicated to be vacant in the documentation used by the House Finance Committee in decision-making processes

- 12 working in medical and dental services, none of which are indicated to be vacant

- 10 positions in human resources, none of which are indicated to be vacant

While these positions will be abolished, some funding will move to support overtime payments for continuing employees.

Liquor Commission Funding and Policy Changes

The largest appropriation change relative to the Governor’s proposal was to shift funds budgeted within the Liquor Commission for transfer to the Granite Advantage Health Care Trust Fund, in support of the non-federal share of Medicaid Expansion, back to the General Fund and out of the expense lines.[42] This $47.1 million reduction was offset by the proposed imposition of premiums on certain Granite Advantage enrollees, as originally forwarded in the Governor’s budget and continued in the House’s proposal, as well as a General Fund appropriation proposed by the House to support Medicaid Expansion.

Under the House’s proposal, the Liquor Commission would have its current enforcement authority eliminated.[43] The Liquor Commission would still have licensing authority, and would regulate licensees such as grocery stores selling wine, but would no longer be enforcing liquor and alcohol laws, including those related to ensuring legal sales.[44]

Youth Development Center Settlements and Justice Department Funding

While the Governor’s budget proposal did not specifically set aside funds for settlements with victims of alleged abuse over decades at the Youth Development Center (YDC) and associated services, the House voted to set aside General Fund appropriations for these purposes.

The House devoted $10 million to fund a specific settlement associated with a single court case. Separately, the House appropriated $20 million to the Youth Development Center Claims Administration and Settlement Fund, $10 million each year of the biennium, to provide more resources to settlements out of court. Based on current State law, the Fund may pay up to $75 million per year in settlements, so these appropriations would provide support only for a portion of that liability.[45]

These appropriations for YDC-related costs were made available to the Department of Justice in the House’s budget proposal. However, those increases were partially offset in the total General Fund appropriation to the Department of Justice by a back-of-the-budget reduction totaling $14.7 million (25.9 percent of Governor’s proposed General Fund appropriations) during the biennium. Funding was also eliminated for the Human Rights Commission, which is administratively attached to the Department of Justice.

Finally, the House voted to require that court or settlement payments made to the attorneys for victims of past abuses associated with the YDC be made on the same schedule as the payments to the victims.

Renewable Energy Fund and the Department of Energy

The Department of Energy includes the Public Utilities Commission and its regulatory authority, and thus falls into the Justice and Public Protection category of the State Budget.

The House voted to change the one-time $10 million appropriation from the Renewable Energy Fund to the General Fund, as proposed by the Governor, to an appropriation of all uncommitted funds in the Renewable Energy Fund to the General Fund during the next State Budget biennium. This change would generate an additional estimated $10 million for the General Fund. These funds flow to renewable energy projects, including solar and wind, under current law.[46]

The House also proposed requiring that all future funding flowing to the Renewable Energy Fund beyond the cost of administration and funding for the Office of Offshore Wind Industry Development and Energy Innovation be credited to the General Fund. Effective in State Fiscal Year 2028, these funds would be credited to all ratepayers on a per kilowatt hour basis, under the House proposal.

Relative to energy policy, the budget proposal from the House includes language that would remove the solar component of the Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard requirements for electricity generation. It also incorporates House Bill 504, a separate piece of legislation that previously passed the House, which would change State energy policy to specifically encourage employing market forces and mechanisms to drive the use of energy resources.[47]

Other Justice-Related Funding, Policy, and Fee Changes

The House voted to make substantial changes to the Governor’s budget proposal relative to justice and law enforcement policies and funding for the administration of justice. These changes included:

- a back-of-the-budget reduction of $7.9 million in General Funds (3.3 percent of Governor’s proposed General Fund appropriations) during the biennium relative to the Governor’s proposal for the Judicial Branch

- a boost in funding of $3.5 million relative to the Governor’s budget proposal for supporting public defenders at the Judicial Council

- the removal of certain financial liabilities for indigent defendants

- the removal of the Governor’s proposed bail overhaul, a version of which was signed into law in late March via a separate piece of legislation, and magistrates would be given duties related to other judicial branch decisions outside of bail[48]

- permitting adults to have blackjacks, slung shots, or metallic knuckles in New Hampshire, repealing the prohibitions on these weapons

- establishing specific labels for firearms made within New Hampshire, requiring that firearms labeled in this manner not be sold outside of the state, and specifically exempting them from regulation by the United States government imposed through the interstate commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution

- specifying that civil rights law does not make classifying use of space or participation in activities by biological sex illegal or unlawfully discriminatory in the cases of multi-occupant bathrooms or locker rooms, participation in sports or similar activities “in which physical strength, speed, or endurance is generally recognized to give an advantage to biological males,” or in corrections or certain types of treatment facilities

- temporarily permits the use of Opioid Abatement Trust Fund resources during the biennium for implementing law enforcement activities for officers participating in substance abuse enforcement programs in Coos, Grafton, Carroll, and Sullivan Counties

Additionally, the House version of the State Budget would make several changes to Department of Safety fees and enforcement impacting motor vehicles. These changes included:

- title, transfer, and registration fee increases for vehicles in statute, as described in the Transportation section below

- increasing the fees associated with vanity plates to $60

- elimination of the requirement that motor vehicles have a safety and emissions inspection annually to be legal to drive on the road, as described in the Transportation section below

- expanding the authority of the Department of Safety to share driver history records with the federal government to include authorized agents of the federal government, as well as uses of out-of-state driver’s license information to help identify voter records

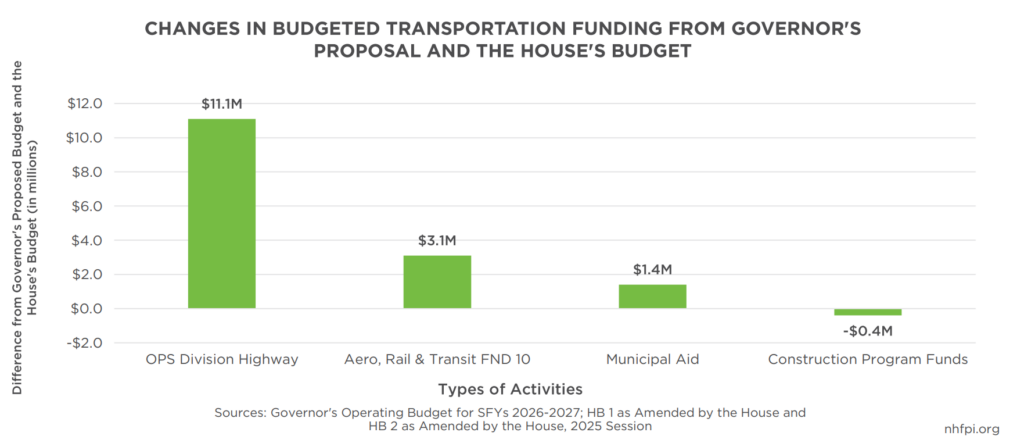

Transportation

The Transportation expenditure category in the State Budget is entirely comprised of the New Hampshire Department of Transportation (DOT) budget and does not include any other departments or agencies. The House’s budget for SFY 2026 keeps funding in line with the Governor’s proposed budget for most DOT activities. The largest DOT increase recommended by the House was $11.1 million in Highway Funds for winter maintenance operations and a retention incentive program. The DOT reported a shortage of winter maintenance drivers in recent years, which has contributed to considerable personnel costs for overtime pay. This initiative may help ensure there are enough drivers to address the State’s winter transportation needs without high personnel costs related to overtime pay or high risk of employee burnout related to extensive overtime during winter storms.

The Aero, Rail & Transit expenditure lines would be allocated $3 million in General Funds for public transit operations under the House’s budget; these funds would be needed to draw down matching federal funds for these operations.

Additionally, to help support the Highway Fund, the House proposed raising motor vehicle registration and license plate fees. The fee increases would generate $15 million in the first year of the biennium and $30 million in the second year, when they would be in effect for the full fiscal year.

The House also included text from House Bill 649, approved separately by the House, that would repeal the annual safety inspection requirement for automobiles as well as the emissions control and inspection requirements. The repeal would reduce State Highway Fund revenue by nearly $5 million during the biennium.

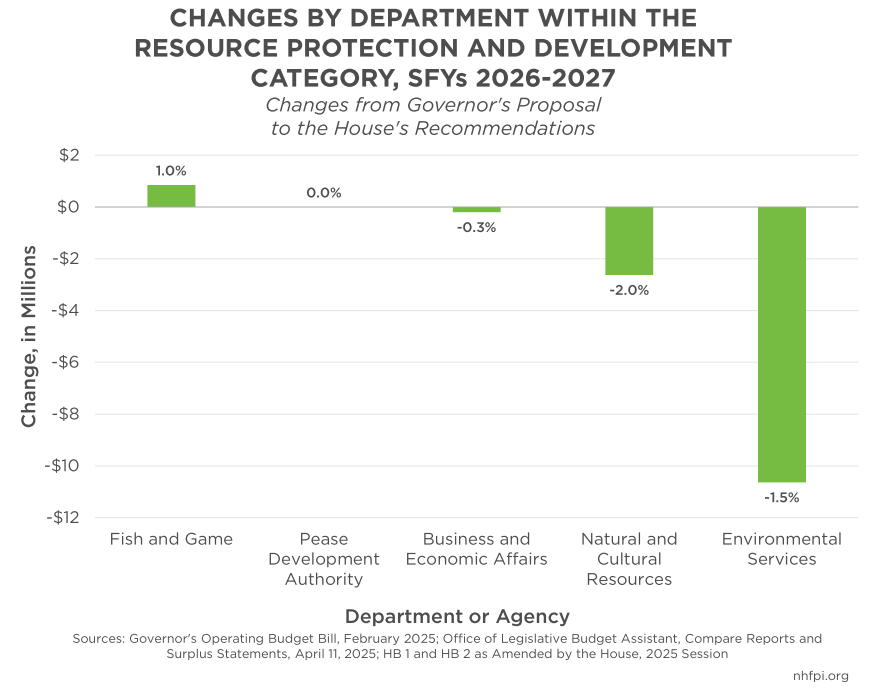

Resource Protection and Development

The Resource Protection and Development category of the State Budget includes the Departments of Environmental Services, Natural and Cultural Resources, Fish and Game, and Business and Economic Affairs, as well as the Pease Development Authority.

Changes recommended by the House primarily increased fees, bringing in more income for State agencies without relying on the General Fund, and altered policies related to permitting, waste, and energy.

The most significant funding changes made within the Resource Protection and Development category was a $6.0 million General Fund back-of-budget reduction to the Department of Environmental Services (DES), which constitutes 10.9 percent of the total General Fund appropriation for DES proposed by the Governor. The House Finance Committee also proposed a $4.6 million (26.3 percent) reduction in State Aid Grants to local governments.

No changes were made to the Pease Development Authority. While the House Finance Committee had proposed closing rest areas and removing funding for travel and tourism development, those proposals were reversed by the full House when the entire chamber was voting on the State Budget.[49] With this reversion, the only change in the budget at the Department of Business and Economic Affairs was the elimination of targeted block grants for planning.

Endangered Species Oversight

The House voted to modify the Governor’s proposal relative to changes to endangered species regulation enforcement. The Governor had proposed requiring State agencies that are seeking to review or approve certain permits to go to the DES, rather than to the Fish and Game Department or the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, for assistance with reviews.

In the House version of the State Budget, the Fish and Game Department would remain the key point of contact for agencies regarding endangered animals, but agencies would also be empowered to hire their own internal wildlife biologists to conduct assessments of risk. Additionally, if agencies are not finished their review process within the 60-day timeline, the proposed House statutory language would make that lack of meeting the approval timeline the equivalent of concluding that a project would not appreciably jeopardize the continued existence of a threatened or endangered species.

The House also voted to remove a $275,000 appropriation, proposed by the Governor, for an environmental scientist position to aid the DES with enforcement.

Changes to Environmental Fees

Relative to the Governor’s budget, the House’s proposal would also increase 29 fees relative to environmental protection, permitting, or agricultural product registration. These fees include charges for registration, licensing, screening, or reviews for dams, hazardous waste generation and cleanup, oil input fees, boat decals, and pesticides. Revenue would also be generated through a $3.50 per ton surcharge on solid waste deposited in landfills or sent to incinerators to support municipal waste reduction and recycling efforts.

The House’s budget would repeal an aquatic invasive species decal required on out-of-state boats, as proposed by the Governor, but would increase a boat decal fee required of all boats that supports the Lake Restoration and Preservation Fund.

The House would retain fees applied to operational permits for public water systems that the Governor had proposed repealing.

The House budget proposal removed the Governor’s recommendation that certain DES fees have an automatic inflation adjustment, and altered the proposed fee structure for terrain alterations to set a baseline fee for the new permit and change the fees that apply to certain volume terrain alterations.

Solid Waste Site Evaluation Committee

The House voted to retain but modify the Governor’s proposal for a Solid Waste Site Evaluation Committee. The House proposed targeted but significant changes to the timelines and requirements of the Committee, including:

- expanding the scope of the Committee’s considerations to include more technical, health, and environmental impacts

- requiring additional information, including regarding economic impacts and greenhouse gas emissions, from permit applicants, including requiring independent, third-party contracting to review applicant information

- removing the General Fund as a potential source of revenue for the Committee and requiring that Committee members not be compensated before the first fees are collected

- delaying new capacity approvals on existing facilities until July 2026 and approvals of new sites until July 2028

Other Environmental Policy Changes

The House voted to remove the Governor’s proposed language that would have required the OHRV trails in the Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest remain open until the second Monday in October each year.

The House’s budget would also add a renewable energy industry representative to Air Resources Council.

General Government

Within the agencies of the General Government category, some of the most significant changes resulted from eliminating agencies, consolidation of agencies, public employee retirement policies, and reductions in aid to municipalities and to potential college students.

Elimination, Defunding, and Consolidation of Agencies

The House voted to eliminate four agencies in the General Government category.

The Human Rights Commission: The House budget would eliminate the Human Rights Commission, which is authorized by a statute passed in 1992. Per that statute, the Human Rights Commission exists to “to eliminate and prevent discrimination in employment, in places of public accommodation and in housing accommodations because of age, sex, gender identity, race, creed, color, marital status, familial status, physical or mental disability or national origin…” This seven-member commission, administratively attached to the Department of Justice, receives complaints, holds hearings, conducts investigations, and issues publications related to the State’s laws against discrimination. In SFY 2023, the Commission reported receiving 767 inquiries and filing 243 charges. Eliminating the Human Rights Commission would reduce General Fund appropriations by $3.2 million during the next biennium, as well as forgo an estimated $366,554 in federal funds.[50]

The Office of the Child Advocate: The House budget proposal would eliminate the Office of the Child Advocate. Established by statute in 2017, the Office of the Child Advocate provides oversight of, and makes recommendations regarding, Department of Health and Human Services programs and decisions related to youth receiving services from the State, particularly from the Division of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF). The Office was established as policymakers were seeking to reduce the chances of children being harmed or neglected while engaged in some level of care with the State after several high-profile deaths of children identified as needing services. In SFY 2024, the Office reviewed information about 2,937 incidents, including 1,510 restraint and conclusion reports, 1,023 residential facility incident reports, and 247 missing child or critical incident DCYF reports. The office was also contacted 349 times during the year. Eliminating the Office of the Child Advocate would reduce total appropriations by $2.2 million, all in General Funds, for the biennium.[51]

The Housing Appeals Board: The budget proposal that passed the House would also eliminate the Housing Appeals Board. Established in 2020, the Housing Appeals Board was designed to serve as a parallel structure to the Superior Court System that would specifically focus on housing-related cases and disagreements. By providing another venue to resolve zoning and other disputes relevant to housing construction, policymakers aimed to speed up the creation of more housing units. Eliminating the Housing Appeals Board would reduce appropriations by $580,595, all in General Funds, in the next biennial State Budget.[52]

The State Commission on Aging: The House also voted to eliminate the State Commission on Aging. The Commission, established in 2019, exists to advise the Governor and the Legislature about policy and planning related to aging, and is attached to the Department of Administrative Services. Total proposed appropriations for the State Commission on Aging in the current State Budget would total $560,864, all in General Funds, for the next two-year biennium.[53]

Beyond individual agencies being entirely eliminated within the House budget proposal, certain operations and programs were eliminated, defunded, or reorganized.

The Division of the Arts within the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources would be both defunded and repealed under the House budget proposal. This repeal would reduce General Fund appropriations by $1.7 million and federal funding by $2.0 million during the next biennium.

The House voted to defund the Prescription Drug Affordability Board. However, the statutory language establishing the Board would remain intact. Defunding the Board would reduce appropriations in the next biennium by $522,224 in General Funds.

Advertising and certain administrative costs for the Granite State Family Leave Plan, the State’s family leave program, would also be defunded in the House budget proposal. The program would be administered by the private contractor who works with the State currently to operate the program. This change would reduce General Fund expenditures in the next biennium by $1.4 million, with no change in other types of funds.

Additionally, the House’s budget proposal would combine the Public Employee Labor Relations Board, the Personnel Appeals Board, and the Right-to-Know Ombudsman into the new Office of State and Public Sector Relations.

Retirement Funding and Policies

The Governor proposed to fund additional retirement costs for certain police and firefighting employees, or “Group II” employees, who had their retirement benefits reduced due to policy changes in 2011. This proposed policy form the Governor was approved by the House. However, the funding structure changed in the House’s proposal with appropriations rising to $27.5 million each year, or a total of $55.0 million for the biennium. This total from the House is a 62.2 percent increase from the Governor’s proposed total of $32.9 million during the entire biennium for added Group II retirement benefits.

The New Hampshire Retirement System would also have a back-of-the-budget reduction in its funding. The New Hampshire Retirement System does not have any General Fund appropriations except for those proposed relative to the Group II retirement changes identified above; the rest of the agency’s budget is funded with the State Budget’s Other Funds category. The back-of-the-budget reduction proposed by the House totaled $8.7 million in Other Funds during the next biennium, which was 22.5 percent of the total Other Funds appropriations proposed for the New Hampshire Retirement System by the Governor for the biennium.

The House Finance Committee had also proposed a “Group III” State employee retirement category that would be a defined contribution program, rather than a defined benefit plan. However, the House voted to change this part of the budget before passage.[54]

Municipal Revenue Sharing

Both current law and the Governor’s budget proposal require the equivalent of 30 percent of revenue collected by the New Hampshire Meals and Rentals Tax to be distributed to municipalities on a per capita basis.[55] The House’s proposal would suspend that statutory requirement for the biennium. Instead, the House would appropriate a fixed $137 million per year for the municipal distribution.[56] The SFY 2025 distribution was $136.6 million.[57] While the House appropriation would be an increase, House revenue projections suggest having the biennium’s appropriation fixed at $137 million would result in $8.9 million less for municipalities, and the total is $11.2 million less than in the Governor’s budget plan.[58]

The House also voted to repeal a prior municipal revenue sharing formula, which has not been used since SFY 2009. Since that year, each State Budget has suspended the formula for its respective biennium, but has not repealed it. The House language would repeal this formula.

Back of Budget Reductions

As noted elsewhere in this Report, the House’s proposed budget would require certain agencies to find savings in their budgets without identifying specific line items through “back-of-the-budget” reductions. These back-of-the-budget reductions total $95.5 million, including $76.8 million in General Funds. Agencies facing these reductions would include:

- The Department of Health and Human Services ($46.0 million in General Funds across the biennium, 2.0 percent of General Fund appropriations proposed in the Governor’s proposal)

- The Department of Justice ($14.7 million in General Funds, 25.9 percent of the Governor’s proposed General Fund appropriations for the Department)