Policymakers in Concord are set to focus on allocating resources for public services in the next State Budget during the next several months. The State Budget provides funds for a wide variety of programs and services, including public health and education, road and bridge maintenance, and protection for both people and the natural environment. While each State Budget offers an opportunity for changes and creativity, understanding the current State Budget and the ways in which New Hampshire’s single-largest public policy documents are typically developed can provide insights into the discussions that will shape the next spending plan. Here are ten facts about the New Hampshire State Budget and how it raises and spends public dollars:

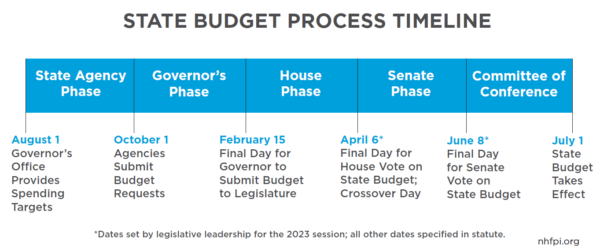

- The New Hampshire State Budget is a two-year plan for spending on State operations, grants to local governments, and contracts with private entities for delivering services. While 30 states have a new State Budget process each fiscal year, New Hampshire is one of 20 states that has a biennial budget, lasting two years. The State Budget process begins with the State agencies compiling information and proposing expenditures to the Governor, a process completed in the year before the Legislature engages with the budget. The Governor then proposes their two-year budget proposal by February 15 in odd-numbered years. Once the Governor’s proposal is public, the House works on the proposal and produces its own version of the State Budget, which is then taken up by the Senate. The Senate creates its own version, and the two chambers meet in a Committee of Conference before the budget returns to the Governor’s desk for acceptance or rejection. The process typically finishes by June 30 of each odd-numbered year, which is when the previous State Budget expires and the State needs new spending authority.

- Not all State spending flows through the State Budget. The State Budget is law, typically comprised of two separate pieces of legislation called House Bill 1 and House Bill 2, which include budget line item appropriations and accompanying policy language, respectively. The Legislature can authorize expenditures through other, separate pieces of legislation as well. The Capital Budget, traditionally called House Bill 25, is a separate, six-year spending plan that can borrow money to achieve balance, while the State Budget cannot rely on borrowed money to be balanced. Specific bills may authorize certain amounts of money for other purposes as well. During 2022, the State Legislature authorized about $363.2 million in new spending or reduced revenues through pieces of legislation separate from the State Budget, according to the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant.

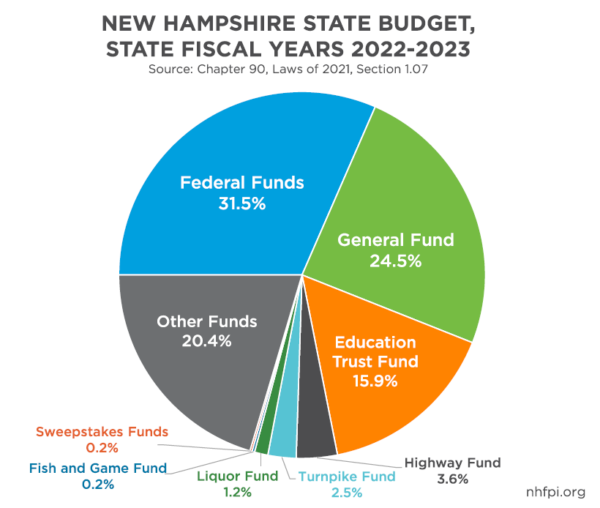

- Almost one in every three dollars of revenue funding the State Budget comes from the federal government. These federal funds come through a wide variety of programs, including Medicaid funding for health coverage, transportation programs, food assistance, water infrastructure projects, aid for affording home heating fuel for people with low incomes, education-related funding for teacher trainings and students with special needs, resources to care for veterans, and many other programs. Many federal dollars must be matched with State funds before they can be accessed.

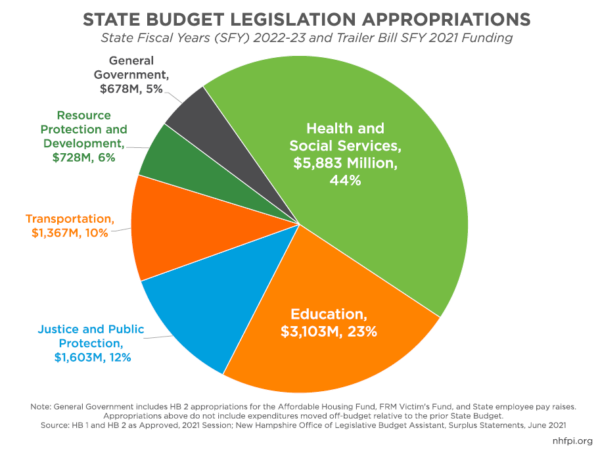

- About two-thirds of the State Budget supports health, social services, and education. The current State Budget’s legislation, including both House Bills 1 and 2 from 2021, appropriates $13.363 billion over two years. Of that total, $5.883 billion (44 percent) supports health and social services activities, which includes most federal and State Medicaid dollars. As of the end of December 2022, Medicaid provided health coverage for about 248,000 Granite Staters, although that figure will likely decline in 2023 as pandemic-era policies end. Health and social services programs also include food assistance through the Supplementary Nutritional Assistance Program, also known as SNAP, which helped about 70,700 children and adults in New Hampshire in October 2022. Health and social services funding also includes programs designed to help address mental health, substance misuse, housing, child protection, and child care needs. Another $3.103 billion (23 percent) in the State Budget is devoted to education. The majority of this funding is in grants to school districts for local public education, but it also includes funding for the New Hampshire Department of Education’s operations and programs, training for police officers, support for the university and community college systems, and funding for the Lottery Commission, which raises revenue for education.

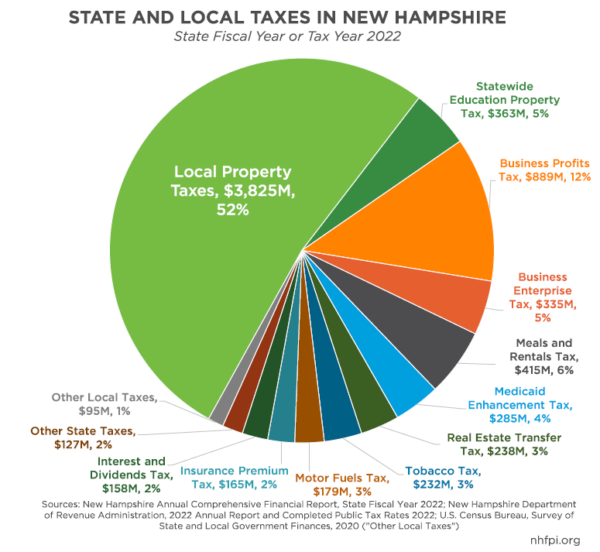

- Funding for the State Budget and State services comes from a wide variety of revenue sources. While the federal government contributes a significant amount of resources to the State Budget and other services outside of the State Budget, other tax and non-tax revenue sources are an important and diverse part of the picture. The State’s largest taxes in fiscal year 2022 were, in order: the Business Profits Tax; the Meals and Rentals Tax on restaurant meals, hotel rooms, and rental cars; the Statewide Education Property Tax; the Business Enterprise Tax; the Medicaid Enhancement Tax on hospital charges for services; the Real Estate Transfer Tax on property sales; the Tobacco Tax on cigarettes and certain other products; the Motor Fuels Tax on gasoline and diesel; the Insurance Premium Tax charged to insurance companies; and the Interest and Dividends Tax. The largest non-tax revenue sources were the Liquor Commission, which operates the State liquor stores; the Lottery Commission, which oversees the State’s lottery operations and charitable gaming; and tolling on the State’s turnpikes. While all State taxes are important to the State Budget and funding services, all raise far less money than local property taxes, which account for about half of all State and local tax revenues combined in New Hampshire.

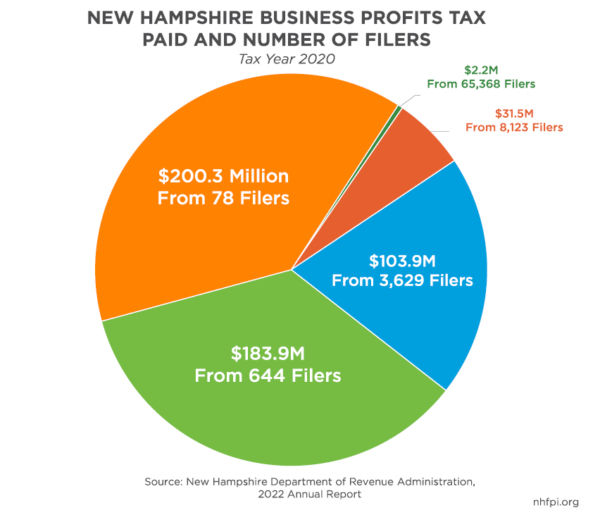

- Two separate revenue sources, the Business Profits Tax and the Business Enterprise Tax, tax businesses operating in New Hampshire, but are very different from one another. The Business Enterprise Tax is based on business operations and other activity that falls into certain categories, including compensation paid. This scope means the tax base is quite broad and the tax rate is much lower. The Business Profits Tax only taxes entities that make a profit, and any Business Enterprise Tax paid can be used as a credit against it. Both taxes have seen their rates repeatedly reduced in the last eight years, but the Business Enterprise Tax has been reduced much more dramatically. As a result, the State is increasingly reliant on the Business Profits Tax; the Business Enterprise Tax rate reductions mean, without adjusting for inflation, revenue from this tax in Tax Years 2019 and 2020 was below the amount collected in Tax Year 2015, before the rate reductions. Business Profits Tax revenues have increased with overall U.S. corporate profits, which have soared since the early days of the pandemic. Large entities pay a significant portion of the Business Profits Tax; in Tax Year 2020, only 78 entities, of the 77,842 that filed for this tax, paid a total of 38.4 percent of all tax revenue collected; the top 0.9 percent of filers paid 73.6 percent of all tax revenue collected. Payments from entities that had at least one significant overseas component of their business generated more than half of the total tax revenue for the Business Profits Tax in Tax Year 2020.

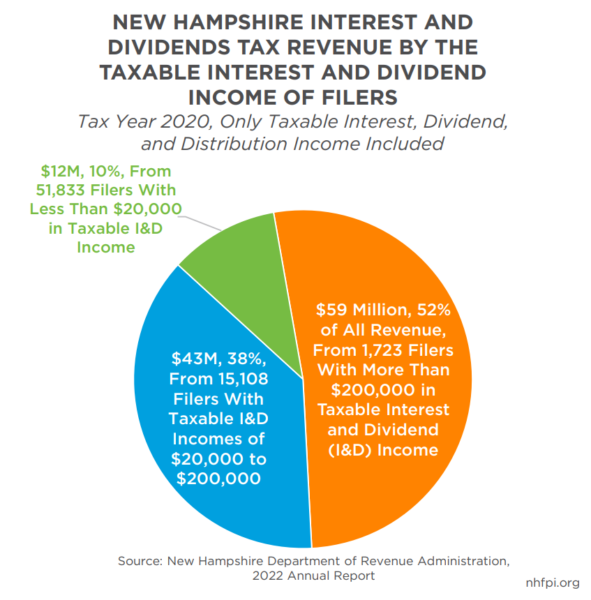

- Starting this year, the Interest and Dividends Tax, which taxes income generated from assets and wealth, is being phased out entirely under current law. Most Granite Staters do not pay the Interest and Dividends Tax, since filers need to receive sufficient income generated by interest, dividends, or distribution income, usually from savings, debt payments, or ownership in a company, such as stocks. Certain income is exempt from taxation, including qualifying employee benefit plans or individual retirement arrangements. As a result, for Tax Year 2020, less than 55,000 filers paid this tax statewide. While the Interest and Dividends Tax collects five percent of eligible income, taxpayers are exempt for the first $2,400 of income for an individual, with additional exemptions for older adults, blind individuals, or individuals with certain disabilities. The Interest and Dividends Tax collected an average of $134.6 million over the last three fiscal years. In Tax Year 2020, about half of the total tax revenue was paid by the top 2.5 percent of taxpayers, who collected more than $200,000 per year from taxable interest, dividends, and distributions, not including salaries and wages, capital gains, or non-taxable income sources.

- The Statewide Education Property Tax is a key source of revenue for the State’s Education Trust Fund, but the State does not actually collect any of the revenue raised by this tax. The State requires local governments to raise a certain amount of revenue locally, based on a statewide tax rate, and use it on local public education. The tax raises a fixed amount of revenue each year that is set in State law. Those tax revenues are kept locally and offset the amount of money the State owes local governments for education funding. In some communities, particularly those with relatively high property values and low numbers of students, the Statewide Education Property Tax raises more than is necessary to pay for the State’s obligations. In those instances, the local governments keep the additional revenue locally. Previously, the State collected those excess revenues and redistributed them to communities that did not have as much property wealth relative to students, but that practice ended in 2011.

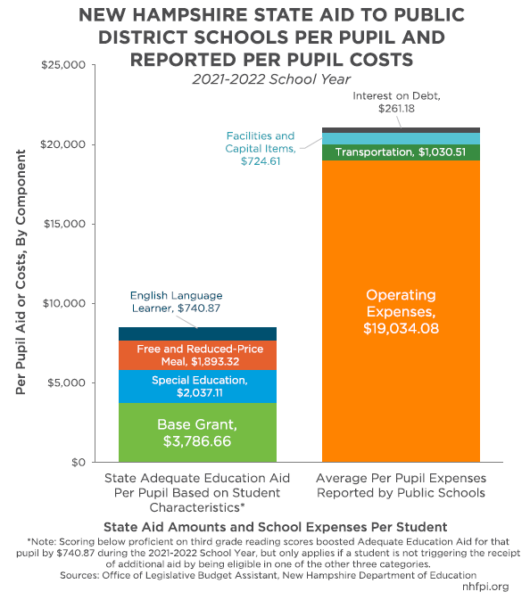

- One of the largest single line items in the State Budget is aid to local governments to support public education, although it represents the minority of funds raised by local public schools. The grants provided on a per pupil basis, with other adjustments for certain student or school district characteristics, are referred to as Adequate Education Aid. Grants are provided based on student population, with additional funding determined by whether a student’s household income is low enough for the student to be eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, if English is a student’s first language or not, if a student has qualifying special education needs, and, in certain circumstances, how a student performed on a standardized third grade reading test. There is also assistance for local schools based on the concentration of free and reduced-price meal eligibility, taxable property wealth per pupil, and other factors based on funding in previous years. On a per pupil basis, the base funding amount per pupil in the 2021-2022 school year was $3,786.66, while school districts reported an average operating cost of $19,399.97 per pupil that year. Reported per pupil expenses rose to $22,948.40 with the inclusions of facility, transportation, and tuition-related costs.

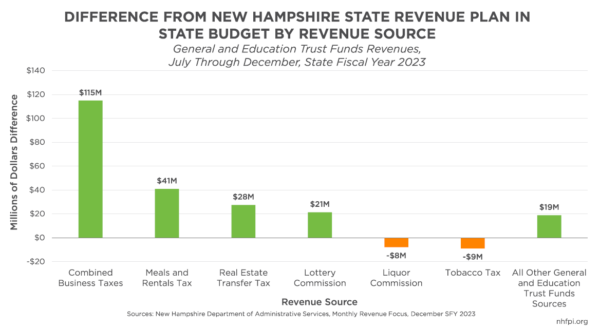

- As of the end of December 2022, the State has a General Fund surplus of $183.4 million, according to the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant. These flexible funds are resources not dedicated to a specific purpose, such as Education Trust Fund or Highway Fund revenues. The surplus total accounts for spending authorized above and beyond the State Budget within this fiscal year, before the next State Budget begins. These surplus revenues, and other recent budget surpluses, have been generated largely by higher receipts from the business taxes than expected, and particularly from the Business Profits Tax, which has benefitted from dramatic increases in overall corporate profits in recent years. Taxes on restaurant meals, hotel rooms, and home and property sales have also performed better than expected, as have revenues from State lottery games. Entering the next State Budget cycle with a surplus gives legislators more resources to deploy for the public benefit. However, the high reliance on business profits for recent revenue growth suggests a slowdown in the economy could substantially impact resources available in the next State Budget.

– Phil Sletten, Research Director