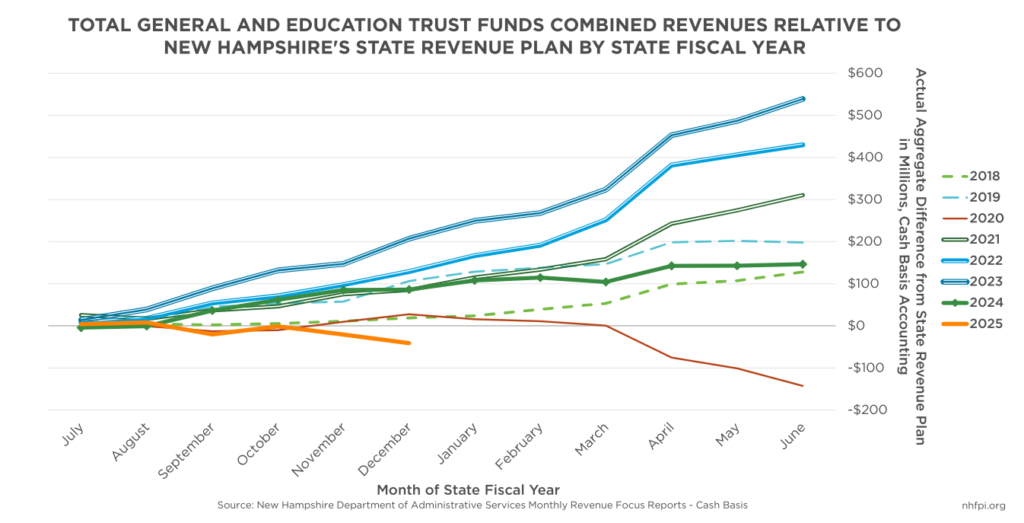

New Hampshire State revenues in December fell short of their target for two key funds by a combined $20.4 million (6.6 percent), nearly doubling the State’s revenue deficit halfway through the fiscal year. December is the second major month of collections for New Hampshire’s two primary business taxes in the fiscal year, which started July 1, and is the last major month for revenue collections before the Governor’s budget proposal is released in mid-February.

The shortfall does not bring the entire two-year State Budget into deficit. While cash-basis combined revenues to the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund are $41.2 million (3.4 percent) below planned amounts, State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024, the previous fiscal year and the first year of the current State Budget biennium, ended with an estimated accrual surplus of $126.4 million (4.0 percent).

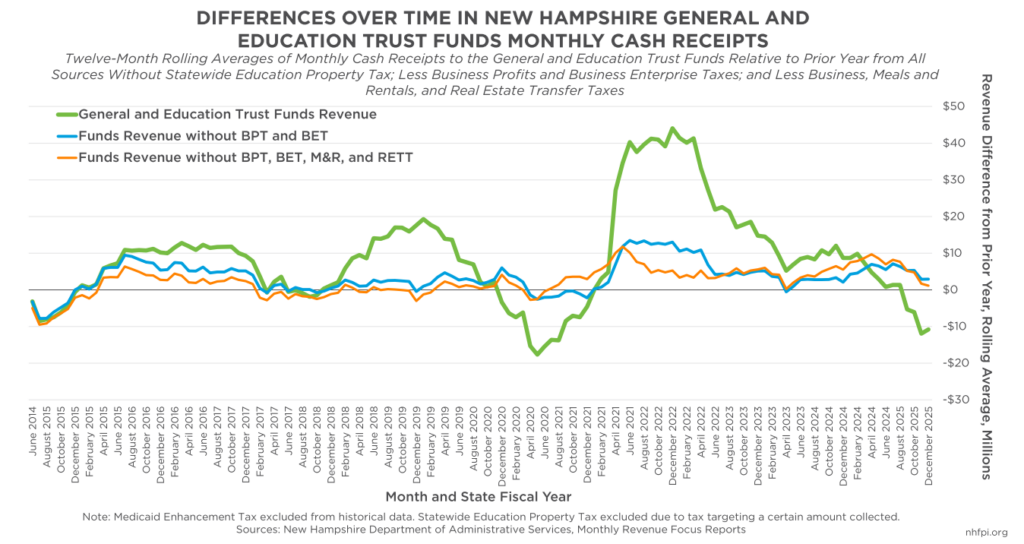

However, revenue trends going into the next budget biennium, combined with policy changes that will continue to reduce available resources for public services, point to a more challenging fiscal outlook for the State. In the first half of SFY 2025, General and Education Trust Funds revenues were $91.6 million (7.6 percent) below collections during the first half of SFY 2024. While this decline has many contributing factors, it has been led by a decrease in receipts from the State’s two primary business taxes.

Business Tax Revenue Continues to Lag Behind Targets

New Hampshire benefitted from significant revenue surpluses in recent fiscal years, particularly during SFYs 2021 through 2023. These surpluses were driven primarily by rising national corporate profits that bolstered the Business Profits Tax (BPT), the State’s largest tax revenue source. The companion Business Enterprise Tax (BET) has had much more limited growth since SFY 2015, in part due to tax rate reductions that were more aggressive than the BPT’s rate reductions during this period.

As national corporate profit growth slowed following the initial boost after the COVID-19 pandemic, the BPT’s revenue increases tapered. State tax policy changes, including rate reductions and changes to the tax base associated with interstate apportionment and credit carryforward limits, likely also put downward pressure on receipts. BPT and BET revenues are lower than they would have been without the rate reductions and certain other tax policy changes implemented during the last ten years.

Combined BPT and BET revenue was below the target established in the State Revenue Plan for December by $23.4 million (12.3 percent), which more than accounted for the entire revenue deficit for the month of $20.4 million. For the first half of the year, combined business tax receipts were $83.7 million (15.5 percent) behind planned amounts, and $83.3 million (15.4 percent) below actual receipts from the first half of SFY 2024. According to the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s month-end reporting, the primary reason why business tax revenues were lower in December was due to a shortfall in quarterly estimate payments relative to the prior year, suggesting that taxable economic activity may have been lower; estimate payments in December lagged payments from the same month last year by about $18.9 million (10 percent).

One of the relatively recent policy changes that may have caused some of the reduction in business tax revenues relative to the State Revenue Plan, which already factored in estimates of reduced revenue from lower business tax rates, is the cap on tax credit carryforward amounts. Starting in Tax Year 2022, State legislators capped the amount of money a business taxpayer can hold, or carryforward, as credit with the State to 500 percent of its liability, requiring the rest to be refunded; that carryforward cap will drop to 250 percent of tax liability in Tax Year 2029 under current law. The impacts of the State, which does pay interest on credit carryforwards, requiring businesses to shift their dollars elsewhere were likely most significant for SFYs 2023 and 2024 revenues. Refunds in SFY 2025, while below last year, remain higher than they were prior to the cap. The impacts of the cap may be ongoing, or business taxpayers may be changing their behavior for other reasons that has resulted in more refund requests.

Declining and Disappearing Revenue Sources

While declines in business tax receipts are the primary reason for the current shortfall, they are not the only cause, nor are they the most recent. Two revenue sources generated the equivalent of 99 percent of the estimated revenue surplus in SFY 2024, and both are disappearing.

Interest and Dividends Tax Repeal

First, the Interest and Dividends Tax, which taxes income derived from wealth, was repealed on January 1, 2025. Tax revenues from the Interest and Dividends Tax have been lower this year than last because of the lowered tax rate, according to the Department of Revenue Administration. While the tax does not apply to wealth-generated income in 2025, tax returns from 2024 will arrive in April. However, the revenue generated by this tax, which increased substantially to about $184 million in SFY 2024, will not be available for the next budget biennia. In SFY 2024, Interest and Dividends Tax revenues accounted for 5.6 percent of total estimated General and Education Trust Funds revenues combined, and 8.8 percent of all General Fund revenue. If the State had not collected Interest and Dividends Tax revenue during SFY 2025 thus far but the State Revenue Plan had remained the same, the revenue deficit through December would have been $78.0 million.

Declining Interest Income from Cash Holdings

The second disappearing revenue source is interest earned on cash holdings by the State. These interest payments continued to be more than originally forecast by the State Revenue Plan but have fallen below the amounts generated last year. State cash holdings, including one-time federal funds, totaled about $2.1 billion at the end of November, a decline from $2.5 billion in September. Interest rates have been generally higher since 2022 than in the decade prior, which has temporarily boosted both interest from cash holdings and Interest and Dividends Tax receipts; however, the federal funds effective interest rate has been declining since August, pushing interest rates down throughout the economy. If interest from State cash holdings had only met the State Revenue Plan, rather than exceeded it, the end-of-December deficit of $41.2 million would have been $55.3 million. Without both earned interest income and Interest and Dividends Tax revenue, the State would have had a surplus of about $900,000 in SFY 2024, and would have a deficit of $112.9 million in the first half of SFY 2025.

With these two temporary revenue sources disappearing and the significant decline in business tax receipts, other sources of revenue have not been able to make up the difference.

Recent Receipts from Real Estate and Meal Purchases and Hotel Rentals Hold Steady

Although Real Estate Transfer Tax receipts appear to have halted their decline relative to planned amounts, they are not rebounding enough to generate a significant surplus. The lack of housing inventory likely limits single-family house sales, keeping revenue growth tepid despite high house prices.

Revenues from the Meals and Rentals Tax, the State’s second-largest tax revenue source, performed well in December with a $2.9 million (12.9 percent) surplus for the month. However, for the year, this tax has generated a relatively limited $5.9 million (3.2 percent) revenue surplus so far relative to planned amounts.

Liquor Commission and Tobacco Tax Receipts Declined, Others Create Small Offsets

While receipts from the Lottery Commission and the Insurance Premium Tax have also generated small surpluses thus far this year, revenues from the Liquor Commission and the Tobacco Tax are behind both collections from last year and the State Revenue Plan.

In total, General and Education Trust Fund revenues over the last 12 months have been, on average, $10.8 million lower each month than they were over the prior 12-month period. While revenue shortfalls from the business taxes have led the declines, total receipts have been slipping, and recent sources of revenue growth have become more limited thus far this fiscal year.

Implications for the Next Budget

These data suggest policymakers could potentially face a General and Education Trust Funds revenue deficit at the end of the fiscal year. Only once in the last twelve fiscal years has the State ended a fiscal year with a revenue deficit. Each fiscal year is unique, and revenues can change substantially in short periods of time. However, from SFY 2007 to SFY 2024, only once (SFY 2013) did a deficit occur in the first half of the year that was followed by a surplus at the end of the year. Conversely, in only one instance was a surplus in the first half of a year turned into a deficit by the end of the year (SFY 2020, due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic late in the fiscal year). Based on this 18-year history, a deficit in the first half of the year was followed by a deficit at the end of the year, or a surplus was followed by a surplus, 89 percent of the time.

A revenue deficit this fiscal year may be offset by last year’s surplus, but any revenue surplus is likely to be much smaller than surpluses of recent years. Policymakers have used surplus dollars during past State Budget cycles to make significant investments, which will likely not be an option this session. A constrained revenue environment, particularly following the disappearance of the Interest and Dividends Tax, may require creative and difficult policy choices to prioritize the greatest needs of Granite Staters in the next New Hampshire State Budget.

– Phil Sletten, Research Director