Student loan debt is the second largest source of U.S household debt, surpassing auto loans and credit card debt and only eclipsed by mortgages. Nationally, student loans totaled $1.34 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. State policies can have a role in reducing tuition costs students face at public institutions, but a new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) suggests states may not be devoting as many resources to containing higher education expenses for students as they did prior to the Great Recession. In New Hampshire, the State government allocates relatively few dollars to public higher education by certain key metrics compared to all other states, and average student debt loads are also the highest compared to those in other states.

The CBPP report draws comparisons between pre-Recession, inflation-adjusted, 2008 funding levels and 2017 funding levels for higher education. In aggregate, states spent 16 percent less per student in 2017 than in 2008, and 44 of 49 states with comparable measures spent less per student over this same period. Inflation-adjusted New Hampshire public spending on higher education per student dropped 26.3 percent, or $1,226, during this time.

This trend in reduced state aid for higher education has two components. First, the CBPP report identifies an underlying long-term movement toward increasing reliance on student tuition payments relative to government support. In 1988, students provided about one-third the amount of revenue to public higher education institutions as state and local governments, while students now provide nearly the same amount of revenue as state and local governments. New Hampshire is one of nine states where tuition revenue was at least twice state and local government funding in 2016. The University System of New Hampshire (USNH) and the Community College System of New Hampshire (CCSNH) together received $132.6 million from the State, according to audited figures for State fiscal year (SFY) 2016; both systems combined collected over $394.5 million in tuition and fees, after deducting student financial aid.

Second, the report identifies the Recession as a key constraint on state revenue collections. Tax revenues fell sharply during the Recession, and 45 percent of the loss in revenues across all states was made up through reducing support for public services, which affected higher education funding. New Hampshire’s budget decisions during the Recession also affected public higher education operations funding, most of which comes through General Fund grants provided to the USNH and CCSNH through the State Budget. Direct funding for the USNH appropriated through the State Budget, unadjusted for inflation, declined from $100 million in SFY 2011 to $51.65 million in SFY 2012, and remains at $81 million for SFY 2018. Changes in budgeting practices make comparisons of all funds for the CCSNH more difficult, but General Fund appropriations dropped from about $37.6 million in SFY 2011 to $23.6 million in SFY 2012, climbing up to nearly $46.5 million in SFY 2018 under the revised funding mechanisms.

In its report, the CBPP also offers state-level details, including some key calculations for New Hampshire. Tuition increased 39.4 percent between 2008 and 2017 at New Hampshire’s public, four-year colleges, which was an inflation-adjusted average increase of $4,424, according to the CBPP report. This rise was the fourth-highest inflation-adjusted dollar increase in tuition in the country; average annual published tuition rose $2,484 nationally, or 35 percent.

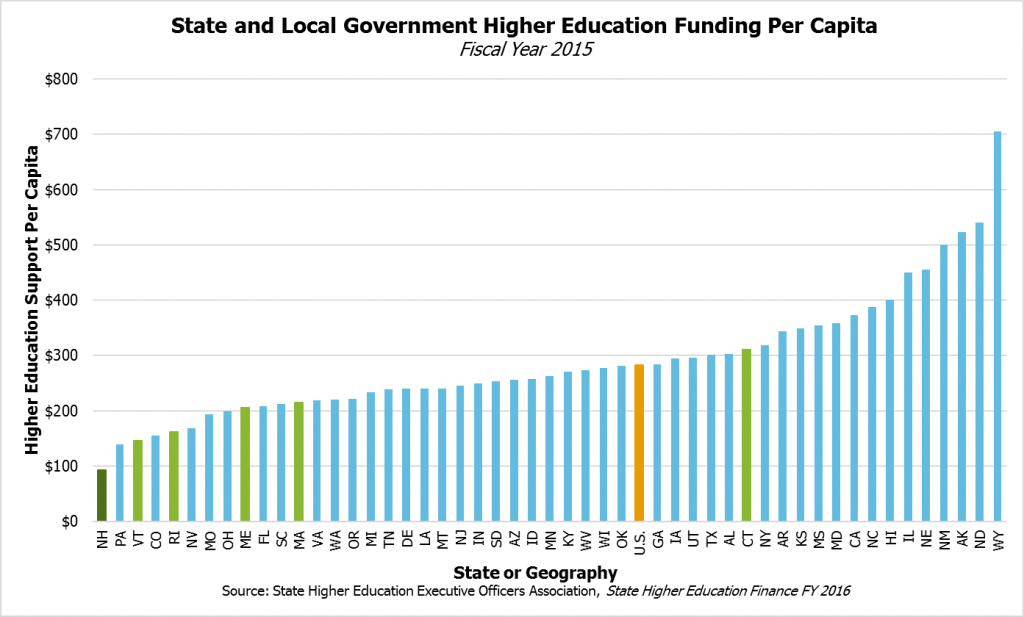

Data provided by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association show New Hampshire’s public funding support for higher education pales in comparison to other states. In fiscal year 2015, New Hampshire had the lowest level of state and local government funding support for higher education per capita of any state, at $93 per person. The next closest state was Pennsylvania at $139 per person, and the national average was $283; the highest figures for fiscal year 2015 were Wyoming at $705 and North Dakota at $541. Relative to income earned in the state, New Hampshire also had the lowest level of public funding support for higher education among the 50 states in fiscal year 2015. New Hampshire’s level of state and local government funding for higher education per $1,000 of personal income was $1.66, compared to the next closest state of Pennsylvania at $2.79 and the national average of $5.90; three states, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Wyoming, devoted more than $10 per $1,000 of personal income. As a percentage of state and local tax revenues and lottery profits allocated to funding for higher education, New Hampshire again came in with the lowest figure, at 1.9 percent in fiscal year 2014. The next closest state by this metric was Vermont at 2.7 percent; the national average was 5.8 percent, and five states spent 9.8 percent or more.

The CBPP report also highlights an increasing student debt load from four-year public institutions, and figures for New Hampshire suggest larger debts on students graduating in-state than nationally. Between 2008 and 2015, average debt incurred by a bachelor’s degree recipient with loans at a four-year public institution nationally grew from $21,226 to $26,800 in inflation-adjusted dollars, and the share of students graduating with debt from a public four-year institution grew 5 percent to a total of 60 percent. For New Hampshire public and non-profit four-year institutions voluntarily reporting bachelor-degree graduate debt data for the class of 2015, The Institute for College Access and Success found New Hampshire graduates who had taken out loans had the highest average debt, at $36,101, of any state’s graduates. New Hampshire also had the highest percentage of graduating bachelor’s degree students who had debt of any state, at 76 percent.

Loans are more likely to be used by students from lower income families. Citing data from CollegeBoard, the CBPP report notes that, for students graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 2011 and 2012, 79 percent from families in the bottom quarter of incomes had student loans, while 55 percent of those with family incomes in the top quarter had loans.

Although other factors must be considered when addressing issues surrounding the affordability of higher education, state policies can play a key role in reducing tuition costs and helping to generate the positive outcomes associated with higher college attendance. CBPP-reviewed research shows higher levels of educational attainment are associated with lower crime rates, more civic participation, better health, and higher wages for workers of all education levels within metropolitan areas. Average weekly earnings generally increase with higher levels of education nationally and in New Hampshire, and unemployment tends to decrease.

In addition, the CBPP indicates research finds college tuition price increases result in declining enrollment, and published tuition price increases are more likely to push lower-income students to enroll in less-selective schools or to decide to not attend college. A higher published tuition price can dissuade students from applying even if the net price, which includes financial aid, remains unchanged. Nationally, inflation-adjusted increases in average tuition and fees at public four-year institutions has outpaced income growth; tuition (without financial aid or room and board costs) at private non-profit colleges in New Hampshire have increased more than at public four-year colleges since before the Recession.

Policymakers may have an interest in encouraging higher education enrollment in-state to address potential workforce challenges. New Hampshire Department of Employment Security projections estimate that, between 2014 and 2024, 36 percent of average annual job openings will be in employment typically requiring education beyond a high school diploma or its equivalent. Policies encouraging in-state college enrollment may also help New Hampshire retain more young workers. Of all states, New Hampshire the highest percentage of its four year college-bound high school graduates leaving to attend college in another state; 59.6 percent of these graduates did so for the fall of 2014, with Utah having the lowest percentage at 10.3 percent. Greater public investment targeted at lowering tuition may encourage college-bound high school seniors to consider remaining in the state, as larger disparities between in-state and out-of-state tuition prices may make New Hampshire schools more attractive to in-state high school graduates.

Given New Hampshire’s workforce constraints and demographic trends, the state’s public institutions of higher education can be key resources for bolstering the economy and productivity. Policymakers made budget choices in response to contracting revenues during the Recession that significantly reduced appropriations to the USNH, and public spending on higher education overall in the state remains very low relative to other states. The size of the total State Budget has risen to a higher level than total amounts prior to the Recession, but inflation-adjusted support for higher education has declined during this time. Support specifically for the USNH remains below pre-Recession levels unadjusted for inflation. Competing priorities are always considered in State Budget processes, and the CCSNH received a funding boost while USNH funding remained flat in the most recent budget. The new State Budget also includes rate reductions to the two primary business taxes that, according to figures generated in the budget process, could reduce revenues by more than the entire annual General Fund contribution to the USNH in the next biennial budget and by that amount each year in the following budget. The increased risk of reduced revenue from these rate changes, as well as a proposed 18 percent reduction in federal Pell Grant aid, the primary source of grant aid, should alert policymakers to potential future challenges students and families may face when paying for higher education in the state and the subsequent consequences for New Hampshire’s workforce and economy.