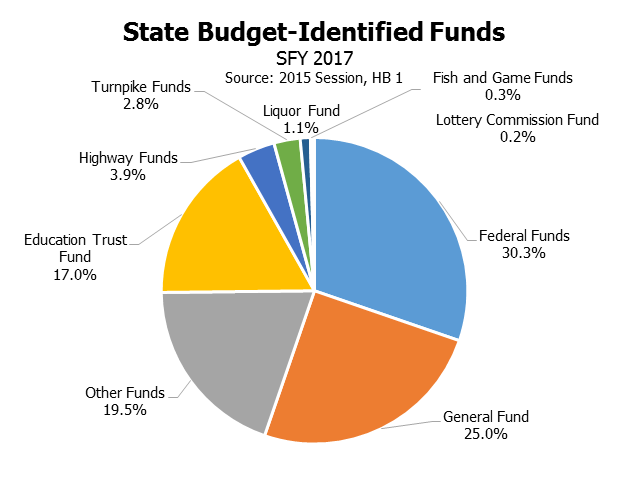

About 30.3 percent of New Hampshire’s state budget is funded using transfers from the federal government for State fiscal year (SFY) 2017. This percentage is slightly below the typical proportion for states. These funds come through a variety of federal programs designed to either promote certain initiatives or priorities at the state level or to otherwise administer programs with the assistance of state governments; examples include health care and education programs and grants supporting transportation, clean water, and housing initiatives. States have some flexibility over these programs in many cases, and sometimes states are also required to contribute a portion of the program’s funding, or matching funds, to receive federal money to implement the program.

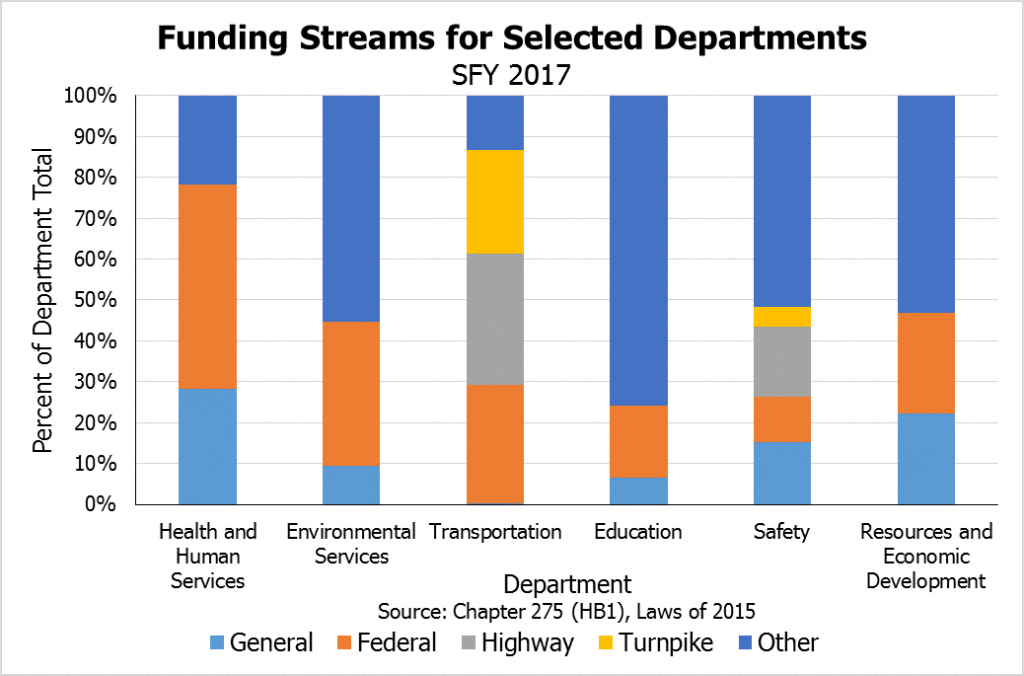

These federal programs touch many different aspects of New Hampshire government’s operations. Federal funds pay for a significant number of operating and programmatic expenses in some key, large New Hampshire agencies, including in SFY 2017:

- 49.8 percent at the Department of Health and Human Services,

- 35.4 percent at the Department of Environmental Services,

- 29.0 percent at the Department of Transportation,

- 24.8 percent at the Department of Resources and Economic Development,

- 17.6 percent at the Department of Education, and

- 11.2 percent at the Department of Safety.

Federal grants and funding also flows to organizations outside of the State government that provide programs and services to New Hampshire residents, such as local governments, non-profits, and directly-administered federal programs.

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget blueprint does not include the full details of his preferences for the federal budget; this part of the federal budget process exists to initiate the budget debate in the United States Congress, which crafts a federal budget resolution to serve as constraints for later appropriations legislation. No information about changes to mandatory spending programs, which do not need to be reauthorized annually, or revenue collection was included in this budget blueprint. Despite this proposal being an early step in the process, enough details exist to identify key changes to federal grants to states and how those changes, if enacted, might impact New Hampshire.

Overall, the proposal includes a cut of 10.5 percent of non-defense discretionary spending in federal fiscal year 2018. The federal Departments of Transportation and Education see proposed reductions of 12.7 percent and 13.5 percent, respectively, which could affect federal grant programs to New Hampshire should those reductions be enacted. Language in the President’s budget blueprint suggested there may be larger infrastructure legislation introduced separately and at a later date, however, that could alter the prospects for transportation funding. The President’s budget blueprint also indicated there would be reductions to funding for certain teacher training programs, which may impact the Department of Education’s budget, and specifically eliminated the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program, which provides non-school hours academic enrichment opportunities for children with a focus on those in low-performing or high-poverty schools and was about $6.4 million of federal funds in New Hampshire’s SFY 2017 budget. The President’s budget blueprint also calls for a 31.4 percent reduction at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; changes include a slight increase to major State Revolving Funds for clean and drinking water received by the state Department of Environmental Services, a reduction in Categorical Grants, eliminations of some regional efforts, and reductions to, or eliminations of, over 50 unspecified programs.

Other changes include eliminating the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which provided approximately $29.3 million in funds for New Hampshire’s Fuel Assistance Program in SFY 2017; New Hampshire policymakers would have to find other funds to support this home heating program, craft a substitute program, or decide to accept the absence of this service. The Weatherization Assistance Program, operated with about $1.4 million in federal grants in SFY 2017, would also be eliminated without action on the part of State policymakers. Budget blueprint proposals to change some funding mechanisms from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to block grants, reduce funding for job training and employment service formula grants, eliminate the Northern Border Regional Commission, help states expand apprenticeships, add $500 million above 2016 federal levels for opioid misuse prevention and treatment services, and boost spending to combat drug trafficking may also affect New Hampshire’s state budget, but the details provided were limited. The information provided here is not exhaustive, and many details have yet to be publicly presented.

The largest dollar changes to federal spending in the New Hampshire budget, however, may come through changes to the federal Medicaid program. Medicaid accounted for approximately 29 percent of all State expenditures in SFY 2016, and more than half (over $1 billion) were transfers from the federal government. Although the proposed American Health Care Act appears unlikely to be revived and pass in the form proposed during the week of March 20, that legislation would have changed Medicaid’s structure, beginning in 2020, to reduce the federal match provided to new enrollees in Medicaid’s expansion population and impose a per capita cap on Medicaid’s growth rate. This, and other changes, would have reduced total Medicaid payments from the federal government to all states by $839 billion between 2017 and 2026, according to the Congressional Budget Office. While the impact of a per capita cap on New Hampshire specifically is not known, the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities analyzed trends in several programs targeted at low-income communities after their structures were changed to block grants. This analysis found that, generally, funding declines over time due to lack of adjustments for inflation and the diffuse use of block grants by states; this second factor renders federal policymakers unable to evaluate program effectiveness and leads to prioritization of other programs instead of increasing funding to block grants.