Policymakers in the State Capitol will focus on allocating resources in the next State Budget during the next several months. The State Budget provides funds for a wide variety of programs and services, including health and education, road and bridge maintenance, and public protection for both people and the natural environment. Understanding the State Budget, how it is developed, and current public needs and trends in key economic and fiscal conditions can provide insights into the discussions that will shape priorities for the next spending plan. Here are seven facts about the New Hampshire State Budget to know for 2025:

1. The State Budget finalized during the next five months will fund public services for the next two years.

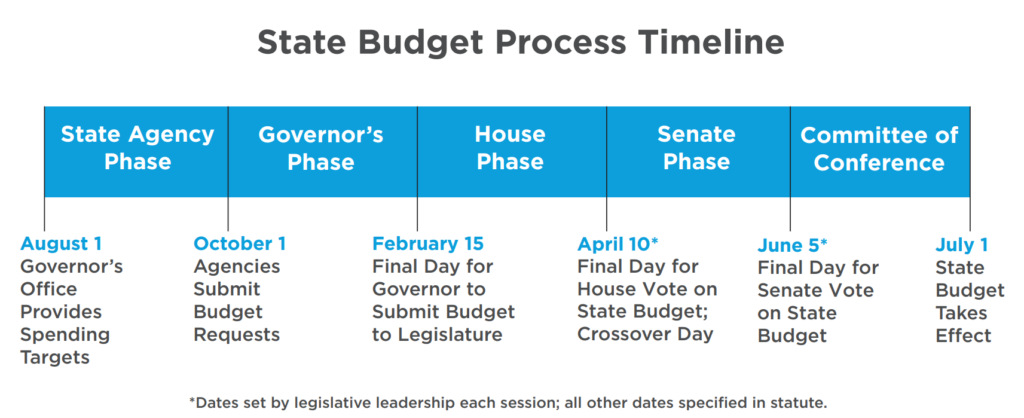

The New Hampshire State Budget is a two-year plan for spending on State operations, grants to local governments, and contracts with private entities for delivering services. New Hampshire is one of 16 states that will enact a biennial (or two-year) budget during 2025, while 31 states plan to approve a one-year budget and three states have different budget cycles. The State Budget process begins with the State agencies compiling information and proposing expenditures to the Governor, a process completed in the year before the Legislature engages with the budget. The Governor will propose her two-year budget proposal by February 15 in odd-numbered years. Once the Governor’s proposal is public, the House works on the proposal and produces its version of the State Budget, which the Senate takes up after the House has completed its work. The Senate creates its version, and if the House and Senate disagree, members from the two chambers meet in a Committee of Conference before the budget returns to the Governor’s desk for acceptance or rejection. The process typically finishes by June 30 of each odd-numbered year, which is when the previous State Budget expires and the State requires new spending authority to operate.

2. Most, but not all, State spending flows through the State Budget.

The State Budget is comprised of two separate pieces of legislation, typically called House Bill 1 and House Bill 2. These bills include budget line-item appropriations and accompanying policy language, respectively. The Legislature can also authorize expenditures through other, non-budget pieces of legislation. The Capital Budget, traditionally called House Bill 25, is a separate, six-year spending plan that can borrow money to achieve balance, while the State Budget cannot rely on borrowed money to be balanced. Specific bills may authorize certain amounts of money for other purposes as well.

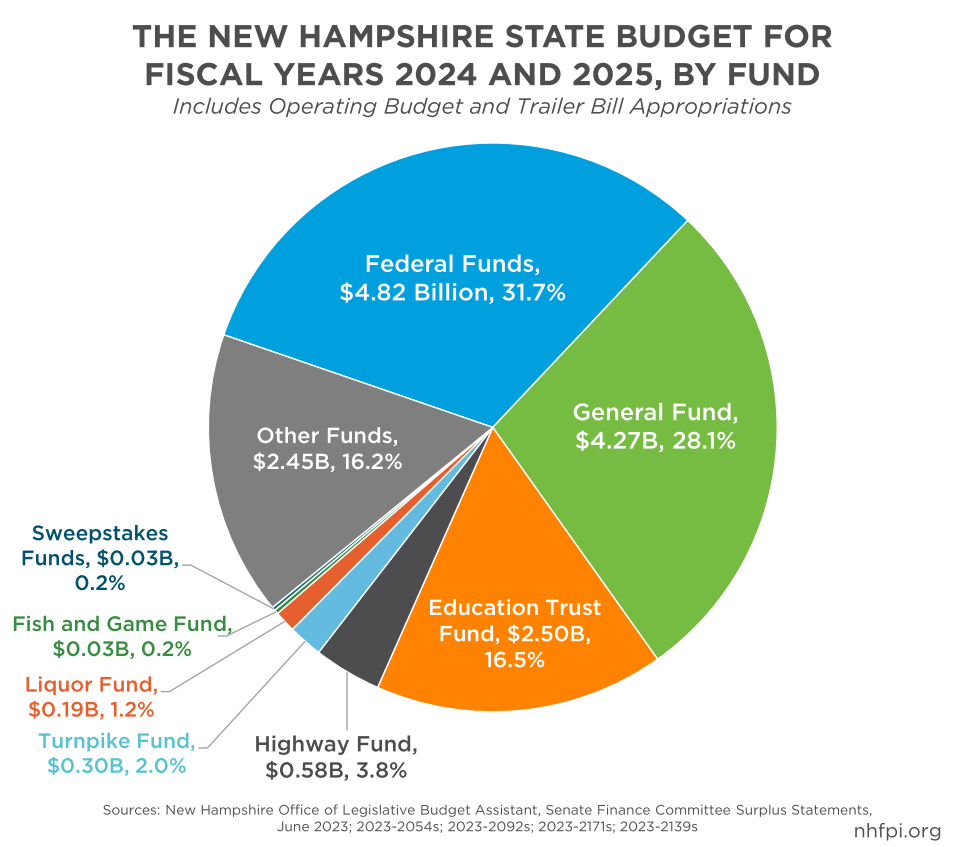

3. Almost one in every three dollars of revenue funding the State Budget comes from the federal government.

These federal funds come through a wide variety of programs, including Medicaid funding for health coverage, transportation programs, food assistance, water infrastructure and other environmental projects, aid to buy home heating fuel for people with low incomes, education-related funding for educator training and students with special needs, resources to care for veterans, and many other programs. Most federal dollars must be matched or otherwise paired with State funds before they can be accessed, including Medicaid, which is the single largest program the State operates. Two key proposed federal changes to Medicaid funding, if they had been implemented and in place this year, would have cost the State an additional $493 million in State funds to maintain the same level of services.

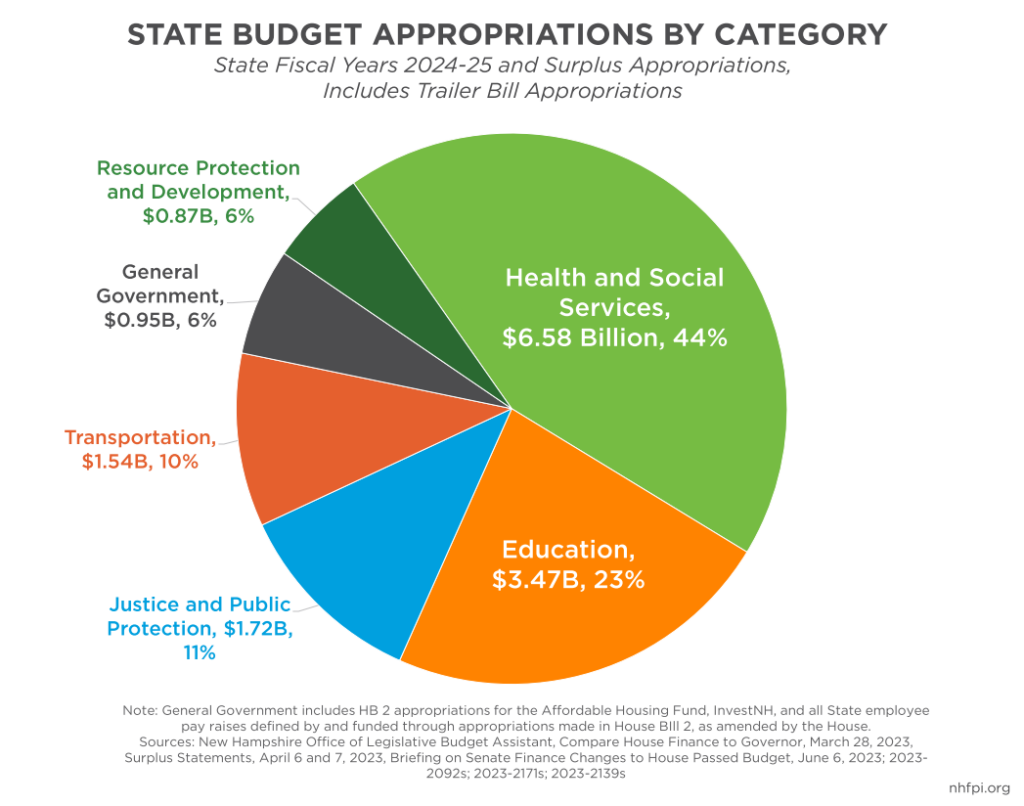

4. The current State Budget substantially expanded key services, including support for access to child care and health services, education funding, and housing.

About two-thirds of the current State Budget, which totaled $15.17 billion for the two fiscal years as enacted, supports health, social services, and education. While housing and child care are very small portions of the entire State Budget, the Legislature made significant investments in these areas in the current State Budget. Policymakers added a total of $50.25 million to the Affordable Housing Fund, the InvestNH Fund to primarily support multifamily housing developers, the Housing Champions Program to promote workforce housing construction, and housing and homeless shelter programs. The State Budget also substantially expanded access to the Child Care Scholarship program to include families with household incomes up to 85 percent of the State Median Income. Budget policy also limited the amount families with low and middle incomes would be expected to pay for child care. Additionally, the formula for State funding to support local public education was altered to boost aid by a projected $169 million relative to prior policy. Relative to health, the State Budget made investments in systems to care for individuals on either end of the age spectrum, including about $67 million for children’s behavioral health and a 50.7 percent increase in appropriated funding for home- and community-based Medicaid services for older adults and adults with physical disabilities. The current State Budget boosted Medicaid services through $134.2 million in State fund investments in Medicaid reimbursement rates to support the health care provider workforce. The State Budget also included substantial increases in developmental services funding and enhanced access to Medicaid eligibility, particularly through reauthorizing the Granite Advantage program.

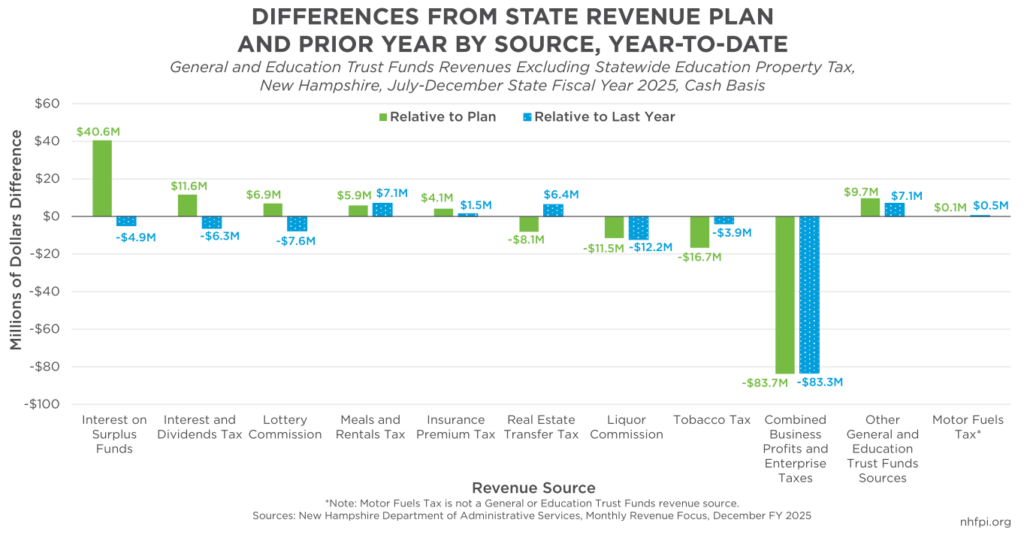

5. Recent State revenue trends are not favorable, and past policy decisions will push revenues lower in the next budget cycle than they would have been without those changes.

The State Budget faced a revenue deficit as of the end of December, which is halfway through the second fiscal year of the current 2024-2025 State Budget. Combined revenues to the General Fund and the Education Trust Fund, which account for about 45 percent of the State Budget and are key for drawing down federal matching funds, are $41.2 million (3.4 percent) below amounts State Budget writers planned for at this point in the fiscal year. Revenue collections for these funds from the first half of State Fiscal Year 2025 were $91.6 million (7.6 percent) below the revenue levels collected during the first half of State Fiscal Year 2024. Revenues are lower for three primary reasons. First, business tax receipts have been substantially lower ($83.7 million, or 15.5 percent, below planned amounts), which is likely due in part to changes in national corporate profits impacting Business Profits Tax revenue, the state’s largest non-federal revenue source, and to changes in policies requiring tax refunds and altering interstate liability calculations. Second, interest revenue the State has collected on cash holdings, which accounted for about half of the revenue surplus in State Fiscal Year 2024, has been declining as one-time federal funds are spent and interest rates fall. Third, the Interest and Dividends Tax, which is a tax on certain types of personal income generated by owning assets such as stocks, has had two rate reductions in the past two years. Revenues look less favorable in the next State Budget in large part because this tax has been repealed effective for calendar year 2025, after generating more than $180 million for the General Fund in State Fiscal Year 2024, or 8.8 percent of all General Fund revenue (or 5.6 percent of combined General and Education Trust Funds revenue); the Interest and Dividends Tax generated nearly half the revenue surplus last fiscal year.

6. Looming and potential costs pose challenges to State finances.

The first variable that has already begun to impact State finances is the ongoing legal cases, and the legal settlements, associated with alleged abuses inflicted on youth nominally in the State’s care over several decades. As of the end of December, the actual settlement amounts paid for 242 resolved claims was $127.2 million, while the 606 pending claims remaining totaled $791.5 million in unresolved requests. The total potential costs under statutory maximums, including resolved and paid, resolved and unpaid, and unresolved claims, are slightly over $1.0 billion. State policymakers set aside $160 million to settle these claims and capped annual payouts at $75 million per year. These costs do not include the results of lawsuits outside of the settlement process. The second major variable is the state Supreme Court’s current consideration of State funding methods for local public education. While the court’s decisions could have widely varying impacts, funding local public education is the second-largest program operated by the State, so substantial changes could necessitate more resources from the State Budget. The third significant variable is any substantial funding changes from the federal government, such as the proposed Medicaid changes that would have resulted in nearly half a billion more in State dollars required to deliver the same services if two components had been fully implemented this year.

7. Some communities will see reductions in State funding for local public education during the next State Budget cycle under current law.

In the first significant instance since the Stabilization Grants were incrementally reduced during 2017 to 2019, school districts will see the potential for a State aid decline because of the recently-reformed structure to the State’s education funding formula. Changes to the funding formula implemented by the current State Budget created a provision to target aid based on a combination of the concentrations of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals and the taxable property value within a school district. However, other provisions were previously designed to target aid based on community characteristics. The Legislature authorized “Hold Harmless Grants” to ensure that no communities received an immediate funding reduction in the current State Budget relative to prior appropriations. Under current law, these grants will drop to 80 percent of their value from this fiscal year starting in the next State Budget. Preliminary estimates suggest that there will be an aggregate $11.8 million reduction in State aid across 134 communities.

– Phil Sletten, Research Director