Medicaid is a fiscal partnership between the federal government and the states designed to support the health of people with low incomes, limited assets, or certain disabilities or health conditions. The Medicaid program provides health coverage, enabling access to health care services, to children in families with low incomes, people with physical or developmental disabilities, older adults, pregnant women, people in need of long-term supports such as nursing facility care or in-home visits, and adults with incomes below or near poverty thresholds.

Medicaid Enrollment and Funding Structure

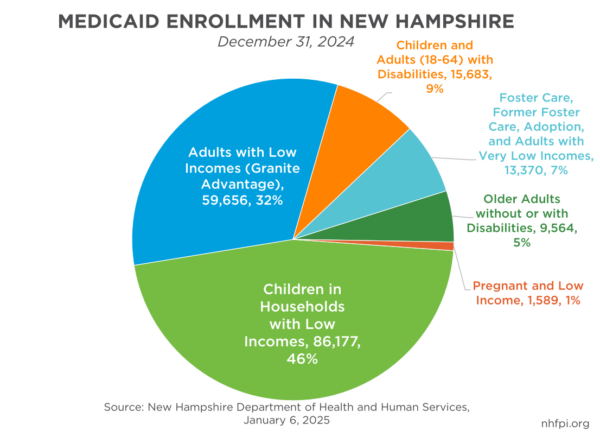

At the end of December 2024, 186,039 Granite Staters, about 13 percent of the state’s population, were enrolled in Medicaid. These enrollees included 90,275 children (48.5 percent of all enrollees), 14,603 adults under age 65 with disabilities (7.8 percent), and 9,564 older adults with or without disabilities (5.1 percent). A key program within Medicaid is the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, commonly referred to as Medicaid Expansion, which was enabled by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and implemented in New Hampshire in 2014. At the end of December 2024, the Granite Advantage program was helping 59,656 New Hampshire adults (32.1 percent of total Medicaid enrollment) with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty guidelines, or $36,777 annually for a family of three during 2025, access health services. Between the initial implementation of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire during 2014 and the end of November 2024, a total of 252,106 Granite State residents have benefitted from being enrolled in the program at least once.

Medicaid is the largest program the State of New Hampshire operates based on the amount of funds invested. All facets of the multi-part program combined were projected to cost a total of $2.57 billion in State Fiscal Year 2025 with $1.43 billion (56 percent) of those funds coming from the federal government, according to January 2025 point-in-time estimates from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. The Granite Advantage component of the program was projected to cost about $620.8 million from that total of $2.57 billion. By comparison, State Budget appropriations for all education services, including aid to local public school districts, was $1.71 billion in State Fiscal Year 2025, and funding for State transportation operations was $771.4 million.

While certain variations exist within the program and are impacted by specific federal and State policy provisions, most components of the Medicaid program in New Hampshire are funded with a 50 percent match from the federal government. This financing mechanism ensures the federal government always pays at least 50 percent of program costs. This 50-50 match conceptually functions as the State investing a dollar into an eligible health service, the federal government matching that dollar, and those two dollars going to support the health of a Granite Stater. This match is called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP).

The base FMAP a state receives varies according to a formula derived from measuring state per-capita income. The formula is designed to help ensure the federal government pays a larger share of Medicaid costs in states with lower per-capita incomes. In Federal Fiscal Year 2025, the highest federal Medicaid match was for Mississippi, which had an FMAP of 76.9 percent. Federal law sets a minimum FMAP floor of 50 percent among the states, and New Hampshire is one of ten states with the lowest rate during this year.

Certain major components of Medicaid have enhanced match rates. Medicaid Expansion, which is the Granite Advantage program in New Hampshire, has a 90 percent FMAP, meaning the federal government funds 90 cents for every dollar spent on the program. The federal government also provides an enhanced FMAP for children with lower incomes, which is a 65 percent FMAP in New Hampshire during Federal Fiscal Year 2025.

Potential Federal Changes to Medicaid and New Hampshire Impacts

The federal government has the authority to make changes to Medicaid. As a federal program, Medicaid’s policy framework is under the control of the U.S. Congress. However, key policy flexibilities related to program implementation are managed by the federal government’s executive branch. For example, Medicaid waivers are established jointly between individual states and the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a federal agency. These waivers, granted by CMS, authorize state programs to deviate from the baseline policies originally established by the federal Medicaid program.

While CMS may exercise some policy creativity in conjunction with states through waiver programs, significant and nationwide changes to the funding structure of Medicaid would very likely require revisions to federal law to be enacted by Congress. Key policymakers have suggested significant changes to Medicaid funding policies. The federal share of Medicaid and associated children’s health coverage accounted for about 10 percent of all United States government expenditures in Federal Fiscal Year 2023.

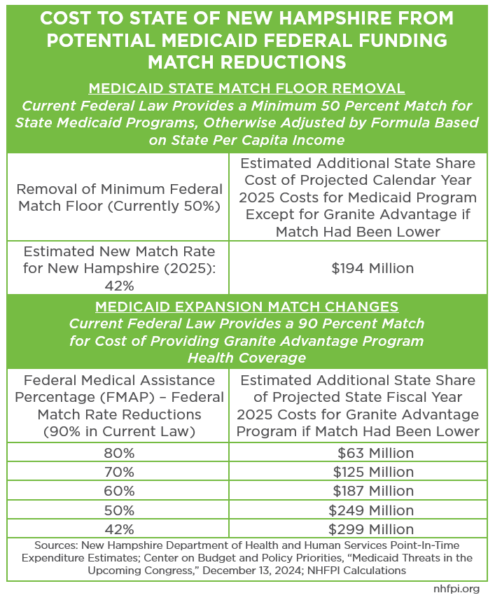

Eliminating the Federal Match Minimum Floor

One of several proposed changes is lowering or eliminating the FMAP floor set at the 50 percent match for states. If this floor were eliminated, New Hampshire’s reduced FMAP would have likely resulted in an additional cost to the State of $194 million in State Fiscal Year 2025 for all parts of the Medicaid program outside of Medicaid Expansion; this figure is based on point-in-time expenditure projections from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and a December 2024 analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities that estimated a 42 percent FMAP for New Hampshire without a 50-50 match floor and a resulting 17 percent increase in non-federal share costs.

For context, $194 million was more money than was collected by any single tax revenue source the State of New Hampshire except for the five largest State tax revenue sources in State Fiscal Year 2024 preliminary data. The entire New Hampshire Department of Corrections has a budget of $177.3 million for State Fiscal Year 2025, while the Division of Behavioral Health has a $173.1 million budget appropriation.

Reducing Enhanced Funding for Medicaid Expansion

Several proposals to lower the FMAP for Medicaid Expansion have also been discussed in recent months, including reducing the FMAP from 90 percent to the regular state matching rate, which would be 50 percent for New Hampshire under current law.

New Hampshire has a law that could trigger the end of the Granite Advantage program if the federal funding structure changes. The law would automatically repeal the program in 180 days if the FMAP for Granite Advantage drops below 90 percent, with notification to enrolled Granite Staters of the program’s end occurring within 10 days.

If this trigger law were altered to permit the program to operate with a lower FMAP, policymakers would potentially need to address the State share’s funding structure. A second State law makes the program’s operation conditional on sufficient funds being available through several different revenue sources, including a significant backstop from the Liquor Commission and a prohibition on the use of General Funds. These revenue sources collectively may not be adequate, under the current structure, to offset an FMAP reduction.

If the Medicaid Expansion FMAP were reduced, the first of these two laws would trigger an end to the program. If the law requiring the 90 percent FMAP law were repealed, the State could still face difficulty complying with the second law or finding other funding sources to support the program, depending on the extent of any FMAP change.

Potential State Costs from Program Changes

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services projected that the Granite Advantage program would cost $620.8 million in State Fiscal Year 2025, with $61.2 million in State-generated contributions. If the FMAP had dropped to 50 percent for this fiscal year, the State would have had to increase contributions to the program by about $249.1 million relative to under current policy for anticipated expenditures during this fiscal year.

If both the federal 50 percent match floor were removed and the Medicaid Expansion FMAP were changed to the base match for other Medicaid programs, the resulting estimated 42 percent base match for Medicaid in New Hampshire would have likely resulted in an additional $493 million in costs during State Fiscal Year 2025 alone. Only three State departments (the Departments of Health and Human Services, Education, and Transportation) have appropriations this fiscal year that are larger than $493 million.

Other proposals to change Medicaid would limit federal funding to states through other mechanisms. For example, the effects of a per capita cap on Medicaid spending could vary substantially by state depending on the structure and growth rates of such a cap. The federal government could also switch from a matching structure to a block grant; block grants typically are structured to provide more policy flexibility to states, but key bock grant proposals discussed in recent years would also reduce funding to states in aggregate.

More Fiscal Uncertainty

Policymakers will face challenges funding current service levels in the next State Budget. State revenues have fallen behind their levels from prior years without adjusting for inflation, and recent history suggests the State is likely to have a revenue deficit this fiscal year. The State also faces several looming costs, including ongoing legal cases and settlements associated with alleged abuses inflicted upon youth in the State’s care, building a new men’s prison, and potential education funding changes resulting from possible State Supreme Court decisions.

Federal changes to the program that helps ensure access to health services for more than 13 percent of the state’s population could have major ramifications for resources available for all State services. Nearly any substantial Medicaid funding change may translate into significant difficulties for legislators crafting the next State Budget in an environment that is already fiscally challenging, particularly while avoiding reductions in access to health services for Granite Staters.

– Phil Sletten, Research Director