Housing in the Granite State is expensive due, in part, to limited availability of housing stock. New Hampshire Housing, the state’s housing finance authority, estimated in 2023 that New Hampshire needed 23,500 more housing units to meet demand that year, and 90,000 more units by 2040. Limited availability is contributing to record-breaking house prices.

In the 25-year period between 1999 and 2024, the median price for single-family houses increased by over 275 percent. Since June 2020, the summer prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, prices increased 63.3 percent, with the median sale price for a single-family house in the Granite State reaching $540,000 in June 2024. Homeowners who purchased a house in 2024 may have approximate monthly mortgage payments of $3,957, inclusive of local property taxes and assuming a five percent downpayment and an average 30-year fixed mortgage rate. This figure, however, does not include other mortgage-related costs like homeowners or private mortgage insurance premiums. Low housing inventory also impacts the price of rental units in the state which, in early 2024, reached a median monthly rent of $1,833 for a two-bedroom apartment inclusive of utilities, a 36 percent increase from 2019.

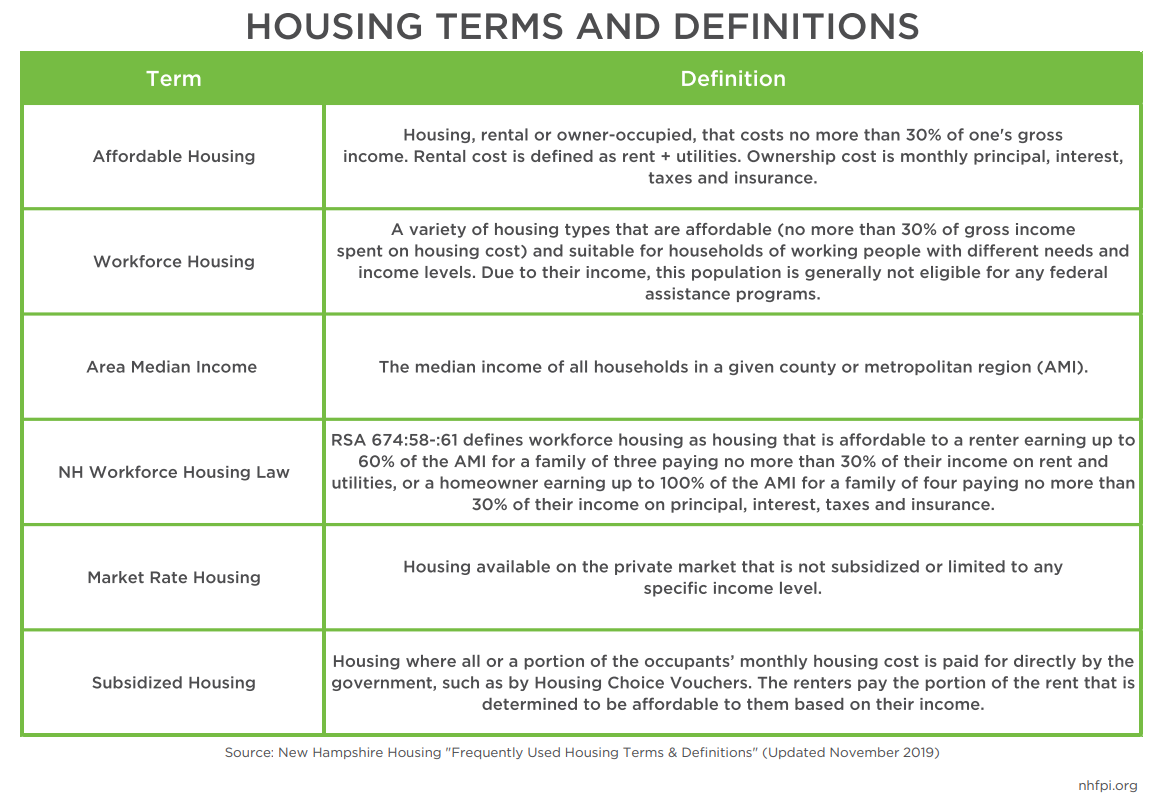

High housing costs may disproportionately impact Granite State renters who, in 2023, had median household incomes ($53,816) that were less than half of the median homeowner incomes ($144,853). Additionally, approximately 51 percent of renters were considered housing cost burdened, defined as paying more than 30 percent of their income toward housing. The need for “affordable housing,” that is, housing that is not more than 30 percent of a household’s gross income, is particularly acute.

Based on New Hampshire’s 2023 estimated median household income of $96,838, affordable housing would cost a median income-earning household no more than approximately $29,000 annually or about $2,420 monthly, inclusive of utility costs for renters.

BARRIERS TO INCREASING AFFORDABLE HOUSING

A confluence of interrelated factors may be contributing to the limited availability of affordable housing in the Granite State, including changing demographics, reduction in housing construction between the early 2000s and 2010s, concerns about local property tax increases, and rates of second homes and short-term rentals in New Hampshire.

Changing Demographics

As of 2023, Granite Staters aged 65 and older comprised about 20.8 percent of the population in New Hampshire. By 2030, the New Hampshire Department of Business and Economic Affairs projects that the population of adults over 65 is expected to be larger than the number of children. Older adults may be remaining in their homes longer, preferring to age-in-place instead of going into a congregate housing setting. At the same time, households are smaller and have fewer children. These demographic trends are reflected in the difference between the percent of New Hampshire households in 2023 with at least one person under 18 (25.3 percent) compared to households with one or more people 60 years or older (47.8 percent). Average household size has also decreased over the past decade, dropping from 2.47 in 2013 to 2.39 in 2023. Having fewer people per household contributes to fewer available units, even if the population remained stable. New Hampshire’s population growth, while advantageous for the Granite State’s workforce and economy, puts additional strain on the state’s housing stock.

Reduction in New Construction and Concerns about Local Property Taxes

New housing construction slowed drastically between the early 2000s and the 2010s. In 2004 and 2005, there were more than 9,000 housing permits issued each year in New Hampshire; however, that rate fell to just 2,101 units in 2011. By 2022, the number of housing permits grew to 5,726 (173 percent increase), with nearly half of permits being issued in southeastern Hillsborough and Rockingham counties. The decrease in construction during this time frame reduced the number of available housing units despite consistent population growth in the state during the same period.

Obtaining approval for housing construction may be difficult in certain municipalities due to perceptions about adding housing units of certain types, the number of children attending local schools, and the impact on local property taxes. The cost of educating students in school districts falls heavily on local taxpayers. In academic year 2023-2024, a total of 70 percent of school district revenue was paid locally by taxpayers, with 61 percent of the total revenue from local taxes and an additional 9 percent from the Statewide Education Property Tax (SWEPT), which is also paid by local taxpayers with the revenue retained locally. Some municipalities may resist additional housing units, particularly multi-family units, based on the unsupported claim that the additional housing will result in more children in the local schools and subsequent impacts on local taxes.

According to research from New Hampshire Housing, however, this concern is not supported by community-level data. Since the 1990s, the ratio of public school children per housing unit has gone down, with less than one student (0.3) per unit in 2023. In other words, there was one public school student for approximately every three units. Higher ratios of public school children per unit were found in communities with higher rates of single-family houses and increased rates of individuals who owned their homes. An analysis of construction between 2014 to 2023 in four case study communities (Deerfield, Dover, Dunbarton, and Merrimack) found that single family houses had, on average, 0.4 public school students per unit (1 student for every 2.5 houses) while multifamily rentals and condos had 0.06 students per unit (approximately 1 student for every 16.7 units) and manufactured homes had 0.01 student per unit (1 student per every 100 units).

The analysis also revealed that new construction in the case study communities resulted in fiscal gains of $1,711 per unit, on average, for the local school districts after accounting for the educational costs of children in families who occupied the new units. Additionally, multifamily rentals and condos had considerably higher net value per acre, at $7,026 and $10,027 respectively, than single-family houses ($533). Taken together, new construction in New Hampshire communities may not result in an influx of children that would result in the need to increase local property taxes. Additionally, school districts may experience increased fiscal capacity to fund their school districts without increases in property taxes because of new housing construction, particularly for condos and multifamily units, even after accounting for the costs of educating new children in the community.

Second Homes and Short-Term Rentals

Seasonal or vacation homes may also reduce available housing units compared to primary residence units. National 2020 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau suggest seasonal units may constitute approximately half of vacant housing. In New Hampshire, the average rate of seasonal, recreational, or occasional use housing in 2020, the most recently available data with reliable municipal-level estimates, was estimated to be 8.8 percent, but varied considerably by municipality.

Seasonal, recreational, or occasional use housing may also be used for short-term rentals (STR) in which owners of a property rent out units to visitors or tourists for a short duration of time. More traditional rental arrangements, in contrast, include landlords renting to tenants for longer durations under a lease or rental contract. Research from New Hampshire Housing suggests STRs may reduce the housing stock available to residents who reside, or would reside if housing were available, locally. A 2023 New Hampshire Housing analysis found that while STRs did not impact median rental rates, they did reduce vacancy rates. This analysis from New Hampshire Housing reported that state-wide rental vacancies may have been reduced by as much as 23 percent due to STR listings between 2014 and 2021. Additionally, the analysis revealed that 43.6 percent of STRs in New Hampshire are owned by out-of-state hosts.

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF LIMITED AFFORDABLE HOUSING

The state’s housing shortage creates challenges to Granite Staters’ well-being. These challenges include slower economic growth, increased strain on family resources, and loss of housing entirely.

Barriers to Population, Workforce, and Economic Growth

Approximately 15.3 percent of New Hampshire residents are approaching traditional retirement age in the next decade. With deaths outpacing births, New Hampshire relies on international immigration and domestic in-migration for population and labor force growth. To support New Hampshire’s population, workforce, and economic growth, housing is necessary for everyone, including young people and families. Currently, young Granite State families, and prospective families, may not be able to find affordable housing. An individual or family unable to move to the state, or within the state to be closer to a job, further constrains the tight labor market, which has nearly two open positions for every unemployed Granite Stater looking for work.

Granite Staters May Not Be Able to Afford to Live Where They Work

Nine of the ten New Hampshire occupations projected to have the highest annual openings between 2022 and 2032 are lower-paying professions with wages below the state median hourly wage of $24.03 in 2023, including cashiers, retail salespersons, food service workers, cleaners, and home health and personal care aides. Without affordable housing for individuals in these occupations, some employees may need to commute long distances. Long commutes can create additional household costs for fuel and tolls. In 2023, the most recently available data suggests that the average commute was nearly 27 minutes for Granite Staters.

Increased Homelessness

Previous research suggests a strong link between rates of affordable housing and rates of individuals experiencing homelessness. According to 2023 data, the New Hampshire Coalition to End Homelessness (NHCEH) reported a 49.5 percent increase in Granite Staters experiencing homelessness since 2020 and a nearly 13 percent increase since 2022 based on data collected year-round from the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS). These figures include percent increases among New Hampshire families (45.8 percent) and Granite Staters aged 55 and older (12.5 percent) between 2022 and 2023. Additionally, NHCEH reported New Hampshire Department of Education data that showed a 7.0 percent increase in homelessness among K-12 students between academic years 2021-2022 and 2022-2023. There were also disparities in the rates of homelessness among New Hampshire’s communities of color and LGTBQ+ residents. Granite Staters identifying as Black or Hispanic of any race experienced disproportionate rates of homelessness compared to the racial and ethnic composition of New Hampshire’s population. Though one in four respondents to the HMIS survey did not report their sexual orientation, the number of New Hampshire LGTBQ+ residents experiencing homelessness who responded to the survey was ten times higher than would be expected based on the number of LGTBQ residents in the Granite State.

Potential trends in homelessness among New Hampshire Veterans were less clear. Point in Time estimates, which are collected once per year during a night in January, suggest the percentage of Veterans experiencing homelessness dropped by 21.3 percent, but the year-long HMIS data suggest a 22.2 percent increase. This discrepancy may have multiple explanations, including more varied homelessness among Veterans throughout the year compared to other populations. In addition, more Veterans experiencing homelessness may access services at centers and shelters that report to the HMIS, thus helping New Hampshire better track this population.

Measuring homelessness rates is fundamentally challenging due to the transient nature of individuals experiencing homelessness and may be exacerbated by policies that might force people to change locations. Due to this challenge, current reported homelessness rates likely underestimate the number of Granite State residents experiencing homelessness.

RECENT GRANITE STATE HOUSING POLICIES AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Several housing initiatives intended to increase the supply of available housing and, in turn, affordability have been implemented since 2023. The implementation of the Housing Champion Program, as enacted in 2023, made $5 million dollars in grant funding available to municipalities that voluntarily meet several requirements including zoning and land use ordinances that support increases in workforce housing. Of New Hampshire’s 234 municipalities, 18 were named New Hampshire Housing Champions in 2024: Boscawen, Concord, Derry, Dover, Enfield, Farmington, Hinsdale, Hooksett, Jaffrey, Keene, Lebanon, Manchester, Nashua, Newport, Portsmouth, Rochester, Salem, and Somersworth. Tracking building permits, available units, and the affordability of future units will be important to determine the effectiveness of this policy.

There were also several housing law changes during the 2024 Legislative Session to increase amount of available housing including reduced barriers to and time for approvals. Changes included potential tax incentives for owners and developers who convert office space into residential space, including mixed-use buildings, easing parking space requirements for certain types of units, and fire code exceptions for buildings with four or fewer units.

Finally, New Hampshire Housing is working to reduce misconceptions associated with affordable and workforce housing through their “Housing Fact or Fiction” series, including highlighting multiple reports that found no evidence that increases in workforce and affordable housing result in influxes of children who cause local property tax increases to fund schools. The series highlights that many people have lived, or currently live, in workforce housing, but do not realize they do; affordable housing and workforce housing were not commonly used historically because most housing was affordable to Granite Staters who were employed.

Without additional investments and enhanced understanding of effective and sustainable polices that support housing access, more New Hampshire residents may struggle to afford to live, work, and thrive in the Granite State.

For more information on the state of housing in New Hampshire, read NHFPI’s fact sheet, “Housing in New Hampshire: Shortage Raises Costs.”

For more information about New Hampshire’s population growth and demographic changes, read NHFPI’s issue brief, “New Hampshire’s Growing Population and Changing Demographics Before and Since the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

– Nicole Heller, PhD, Senior Policy Analyst