On April 5, the New Hampshire House of Representatives passed an amended version of expanded Medicaid reauthorization that modifies the work requirements outlined in the State Senate’s proposal and makes a variety of other, smaller changes. The House accepted the amendment from the House Health, Human Services, and Elderly Affairs Committee and voted to move the bill to the House Finance Committee for a second review.

Approximately 52,000 low-income Granite Staters rely on expanded Medicaid for access to health care, and the State Legislature must reauthorize the program for it to continue beyond the end of this year. For more information on New Hampshire’s current expanded Medicaid program and the State Senate’s proposal, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief: Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

The House Committee Amendment and Other Recent Developments

The House Health, Human Services, and Elderly Affairs Committee amendment alters the work requirements, which the State Senate set at requiring 100 hours of qualifying activities per month, to require an average of 600 hours over six months, both based on an average of 25 hours per week. Many details of the implementation of the work requirements are not described in the proposed statute, but setting the required time window at six months, rather than a set number of hours per month or week, reduces the chances that an individual would lose health insurance coverage due to a job loss, seasonal employment, unexpected variations in hours, or a life event that does not qualify for a work requirement exemption. The amendment also adds self-employment to the list of qualifying work activities.

Additional changes in the House Health, Human Services, and Elderly Affairs Committee amendments include requiring that future mandatory evaluations of the expanded Medicaid program ensure that incentives, cost transparency, and efforts to control medical procedure costs have been effective at lowering costs while also maintaining both quality and access and accounting for changes in health parameters. The commission established to evaluate and make recommendations surrounding the expanded Medicaid program was amended to change how certain members were appointed, and the word “physicians” was changed to “providers” in one passage related to primary care visits.

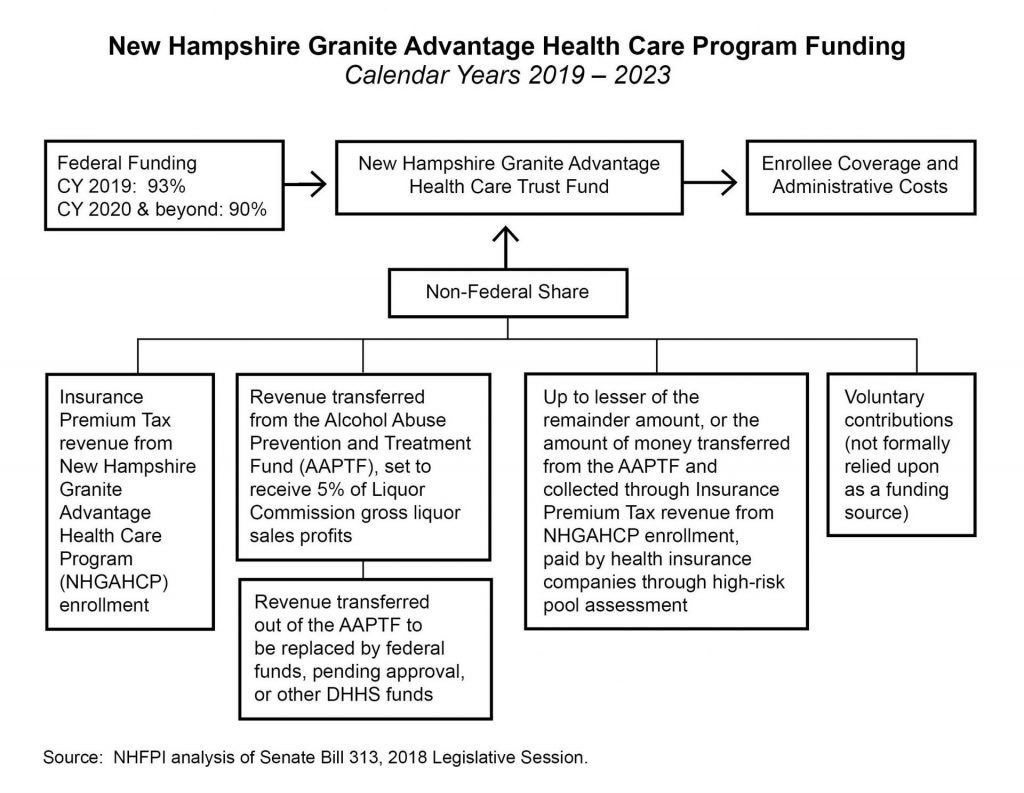

The State Senate’s proposal funding structure, which will now be examined by the House Finance Committee, moved dollars from the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund to pay for the non-federal share of expanded Medicaid. The recent announcement that New Hampshire hospitals would donate to the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund over the next five years likely alters the debate around the Senate proposal’s funding structure for the non-federal share. The federal share is at least 90 percent of enrollee costs for the program going forward.

National Research Concerning Medicaid Work Requirements

Historically, Medicaid has not included work requirements, as they were not seen as furthering the program’s purposes of promoting health coverage and access. New Hampshire is one of three states with a pending waiver request to impose work requirements solely on adults enrolled in expanded Medicaid, while seven other states are seeking to implement work requirements for the traditional Medicaid population as well, including some segments of the population not covered in New Hampshire’s traditional Medicaid program.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released new guidance in January 2018 indicating states may seek federal waivers to impose work requirements on certain non-elderly adults enrolled in Medicaid. The guidance required some exemptions and suggested others, such as alignment with exemptions, protections, and allowable activities for fulfilling work requirements under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. This guidance cited research showing higher incomes are correlated with longer lifespans, negative effects of unemployment on mental health, and associations between community engagement activities such as volunteering and improved health outcomes. This guidance is not a formally proposed new rule, despite the potential impact, and leaves states with considerable flexibility.

The Kaiser Family Foundation noted, following the release of the new guidance, that researchers have had difficulty determining the direction of causality between work and health, as improved health could lead to a greater ability to participate in work. Other researchers have noted that work requirements in TANF do not increase long-term employment, did not increase stable employment in most cases, and left most of those with jobs in poverty, with mixed or limited effects on income growth.

Additionally, research indicates many Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide are already working. Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that, in 2016, 60 percent of non-elderly adult Medicaid recipients without Supplemental Security Income (SSI, designed to help elderly, blind, or disabled people with little or no income) nationwide, and 65 percent in New Hampshire, are working. The percentage of non-elderly adult Medicaid recipients without SSI in a family with at least one member working is estimated to be 77 percent in New Hampshire, with 49 percent of those who are not working indicating their reason for not doing so is illness or disability.

Researchers affiliated with The George Washington University and writing for Health Affairs found that, among the 2015 population covered by expanded Medicaid, 48 percent had a permanent disability, serious mental or physical limitations, or are in fair or poor health. Of the remaining portion covered by Medicaid expansion, all but one quarter were working, seeking work, or in school. In total, 87 percent were either in the roughly half of recipients who might not be considered “able-bodied,” in school, working, or seeking work. Of the remaining 13 percent, three quarters reported not working to care for family members. The authors also separately concluded that non-working Medicaid beneficiaries potentially subject to work requirements need more health care than those who are working, with higher rates of hospitalizations and doctor visits and three times the likelihood of already working enrollees to have seen a mental health professional in the past year.

Lack of work hour requirement flexibility, documentation hurdles, and administrative capacity challenges are other concerns identified by researchers. A new study from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) examined the potential impact of Kentucky’s 80 hour per month work requirement as approved by the federal government. Using U.S. Census Bureau data tracking the number of hours worked weekly by respondents, the CBPP study finds that close to half of all low-income workers who could be affected by a Medicaid work requirement policy like Kentucky’s would be at risk of losing coverage for one or more months. The study finds that even for those working 1,000 hours per year, which averages about 83 hours per month, about one quarter of the population could be at risk of losing coverage because they did not meet the work requirement every month.

Unstable employment opportunities and volatile hours, which may change substantially on a weekly basis, play key roles in the inability to maintain a work requirement. The accommodation and food services sector nationwide saw the instances of people leaving their jobs total 72.5 percent of annual average employment during 2017, compared to a rate of 43.0 percent for all jobs, suggesting considerably higher turnover in the sector; the retail sector saw a rate of 53.0 percent. Food service workers also had the lowest median tenure of any job, based on September 2016 research from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retail remains the largest employer in New Hampshire, and the accommodating and food services sector added the third largest number of jobs of any sector in New Hampshire between 2008 and 2016. The importance and seasonal nature of the tourism industry in New Hampshire may affect the number of hours a low-income worker is able to find work during any given month.

The existing resources available to individuals on Medicaid may affect the ability to comply with work and reporting requirements as well. A study from the Urban Institute of Kentucky’s non-exempt, non-working Medicaid recipients identified 25 percent do not have internet access and 11 percent do not have access to a vehicle in their households, suggesting they may encounter substantial barriers to work and limitations on the ability to comply with documentation requirements.

The work requirement in existing New Hampshire law, which is the basis for the pending federal waiver request but may be modified by any new law reauthorizing expanded Medicaid, requires between 20 and 30 hours per week of qualifying work activities depending on the number of years enrolled in the program. Moving to longer timeframes for the requirements, such as the six-month period proposed in the version of Senate Bill 313 that passed the House on April 5, helps to mitigate some of the concerns associated with unstable work hours raised by the research while still requiring the same number of qualifying hours for work or community engagement. However, important details are unresolved that would clarify the levels of barriers individuals may face in meeting the requirements.

To learn more about the existing work requirements in State law, see NHFPI’s post Medicaid Expansion Work Requirements Hinge on Federal Approval. For more on the work requirements as proposed by the State Senate, see NHFPI’s Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.