Economic conditions overall have vastly improved since the initial swift and severe impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. However, the uneven impacts of the pandemic on certain groups of workers and industries, and the recovery not yet reaching all of those most affected, has resulted in lingering economic challenges in New Hampshire. Proactive policy solutions and strategic targeted investments designed to bolster an equitable and inclusive economic recovery can provide key support, while strengthening the long-term well-being of Granite Staters throughout New Hampshire.

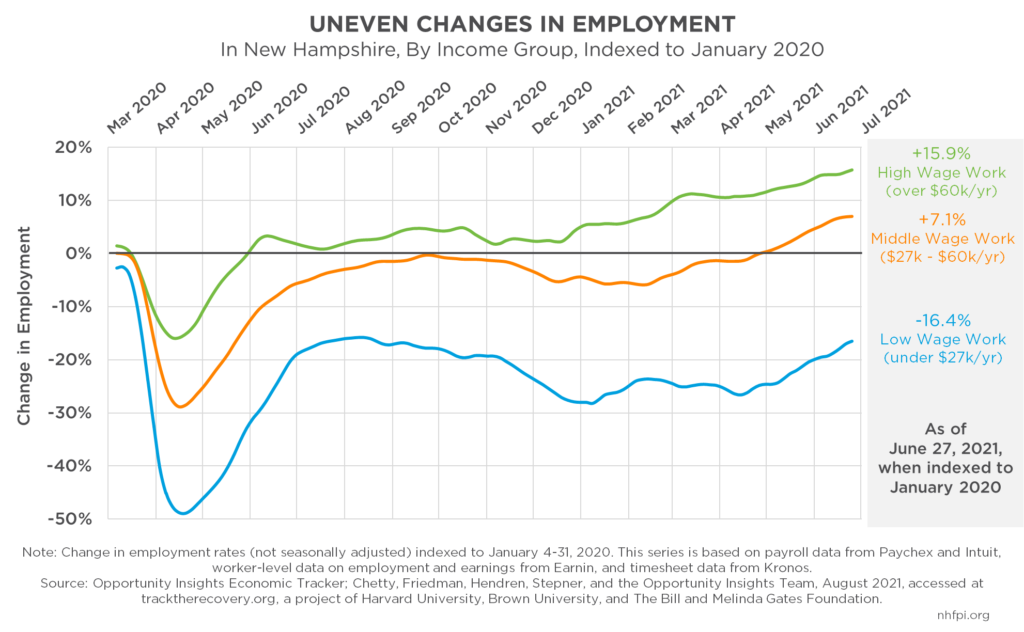

Both nationally and in New Hampshire, the COVID-19 crisis led to massive and uneven employment impacts throughout the economy. Industries and regions of the state more heavily reliant on service-based work, or other work models that could not easily transition to more limited public interaction, faced the largest employment losses. Many of these service industries paid lower wages, suggesting that workers in New Hampshire earning lower incomes were most impacted by lost or reduced wages, affecting their economic security. Analysis shows that lower wage employment was estimated to be 16.4 percent below pre-pandemic levels in New Hampshire in late June 2021. While the state’s unemployment rate has dropped to pre-pandemic levels, other data show that overall employment remains lower than pre-pandemic levels, with fewer people participating in the workforce due to key challenges such as the limited availability of childcare.

Key federal pandemic-related aid has provided New Hampshire with significant resources to mitigate the economic and health impacts of the pandemic. More recent targeted and flexible aid available to the State, county, and municipal governments through the American Rescue Plan Act provide policymakers with significant latitude to respond to the immediate needs faced by many workers disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Additionally, federal flexible aid allows for strategic investments to support a recovery that leads to a more resilient and productive economy for Granite Staters.

This Issue Brief examines key aspects of the uneven effects on employment caused by the COVID-19 crisis. Analyses in this Issue Brief discuss the disparities resulting from these uneven impacts, the groups of workers most acutely affected, and the ongoing economic recovery. This Issue Brief also explores key provisions of recent federal aid available, and opportunities for investments that support those most impacted by the pandemic and promote greater economic security, mobility, and resiliency in New Hampshire’s labor market.

Statewide Employment Conditions During the COVID-19 Crisis

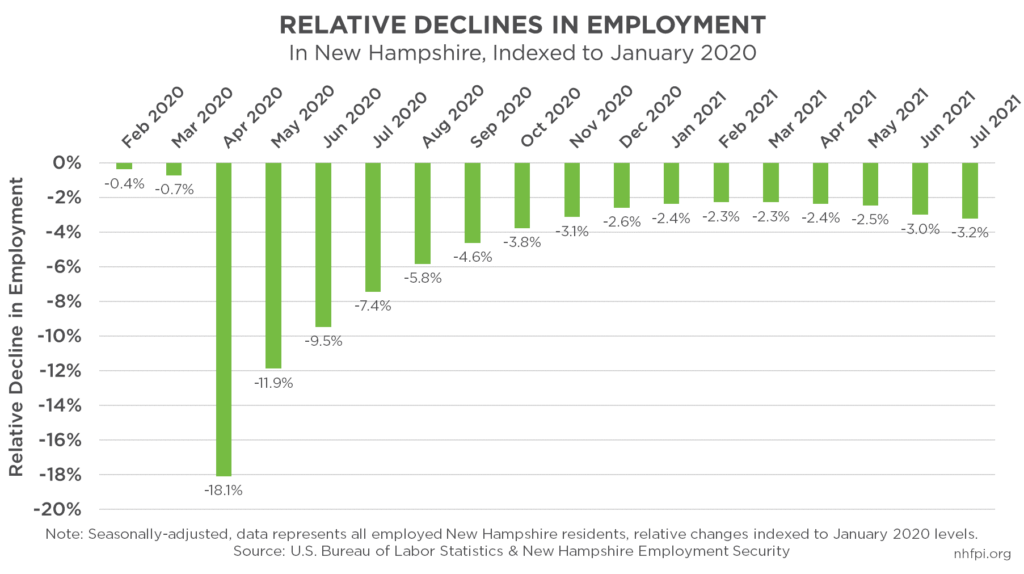

New Hampshire’s economy has rebounded, albeit unevenly, since the initial impacts of the COVID-19 crisis that resulted in significant employment reductions. These employment declines were most concentrated among industries that required in-person interactions, industries paying lower wages, and regions with large service-based sectors. Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security show the severe declines in employment when indexed to pre-pandemic levels from January 2020. These data are seasonally-adjusted, allowing focus on the direct impacts of the pandemic, with less emphasis on the cyclical, seasonal ebbs and flows of employment in more normal times.[1] Despite the estimated unemployment rate returning to below 3 percent, matching pre-pandemic levels in New Hampshire, relative monthly levels of total employment remain below previous employment levels, and have declined further in recent months. In July 2021, the total estimated number of New Hampshire residents employed was about 3.2 percent lower than in January 2020.[2] The trajectory of the ongoing recovery is dependent in part on how public policy directs resources to support residents and the economy.

Prior to the pandemic, the economy in New Hampshire was continuing to expand after the Great Recession, which ended more than a decade ago. The continued declines in overall levels of employment in the state due to the COVID-19 crisis have occurred over a period during which job growth was expected were it not for the pandemic. As a result, the actual deficit in employment, relative to a world without the pandemic, is likely larger.[3] One factor contributing to the continued suppressed levels of employment, despite the low current levels of officially-estimated unemployment in New Hampshire, is the reduced size of the labor force in the state and fewer people participating in the workforce.[4]

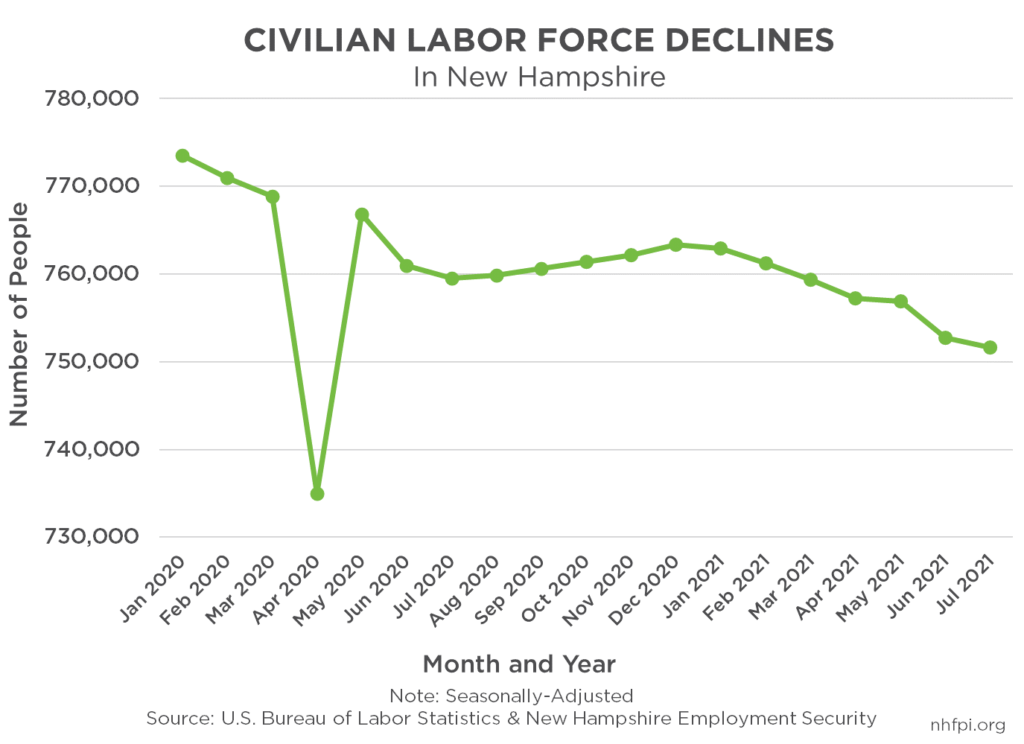

The civilian labor force measures all individuals in the workforce, which includes individuals who are over the age of 16 and are classified as employed or unemployed, indicating they either have a job, or do not have a job and are available to work and have searched for work in the last four weeks.[5] The labor force is still below pre-pandemic levels; the seasonally-adjusted July 2021 labor force in New Hampshire is estimated at about 17,200 fewer individuals than March 2020 levels, which were measured just before the onset of pandemic’s employment impacts in the state. This decline in the labor force in New Hampshire throughout the pandemic indicates that fewer individuals were employed or searching actively for work while unemployed, and the current relatively-low levels show many individuals have not been able to return to work.[6]

There is an important interaction between the labor force and the official estimate of unemployment: the official estimated rate of unemployment only counts individuals in the labor force who are (or very recently were) actively looking for work and have not found employment.[7] Resultingly, reductions in the unemployment rate may not be indicative of a recovery of the overall employment losses. The official estimate of unemployment does not capture individuals who have lost their jobs and stopped searching for work, referred to as discouraged workers, or individuals who are working part-time when they want to be working full-time.[8]

Uneven Employment Impacts

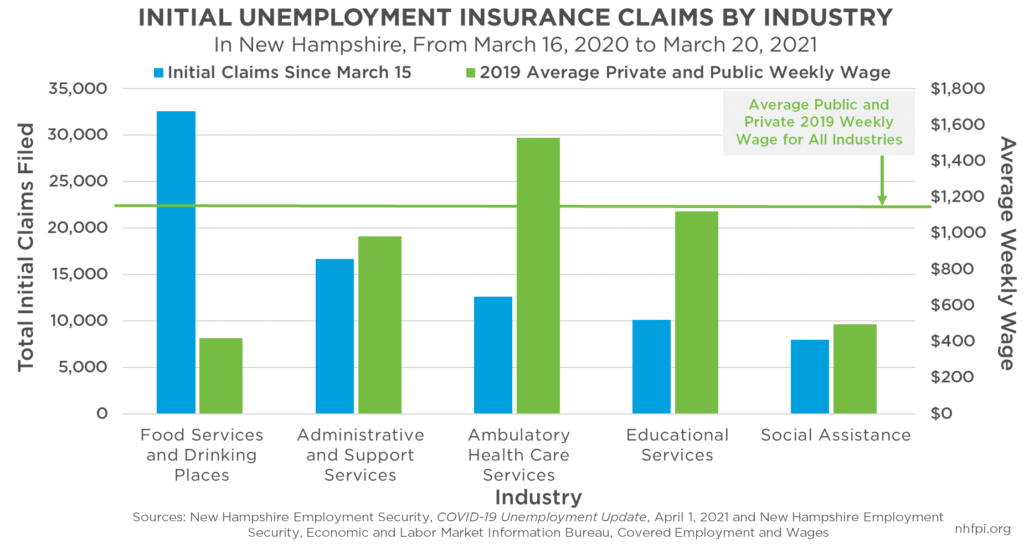

In response to the employment impacts of the pandemic, state and federal expansions to unemployment insurance eligibility aided those facing employment or income reductions. Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security tracking these unemployment claims by industry highlight the disproportionate employment reductions among certain industries in New Hampshire. The data encompassing the year following the pandemic’s initial impacts, from March 16, 2020 to March 20, 2021, show that of the top five industries generating the most unemployment insurance claims, four paid lower-than-average wages. This indicates that the employment and employment income losses in New Hampshire were most severe among workers who entered the crisis earning lower wages.[9]

Utilizing private-sector employment survey data, analysis from researchers at Harvard University and Brown University shows that employment levels for work classified as low-wage experienced the largest reductions throughout 2020 and the first half of 2021. Additionally, employment levels for work classified as low-wage is still stifled when indexed to pre-pandemic levels in January 2020. This analysis finds that in New Hampshire, all employment declined significantly in April 2020, albeit unevenly. Additionally, the recovery of employment is uneven as well, with low-wage employment, characterized as work with earnings of less than $27,000 per year, having not recovered in New Hampshire as of June 27, 2021. Low wage employment is estimated at 16.4 percent below pre-pandemic in the state. Middle wage employment, characterized as work with earnings of between $27,000 and $60,000 per year, recovered more quickly than low wage work, and has grown 7.1 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels. Finally, high wage employment, characterized as work with earnings of greater than $60,000 per year, recovered the fastest, and has grown 15.9 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels.[10]

The trends revealed in this analysis reaffirm the conclusions drawn from the unemployment claims data that the difference between current employment estimates and pre-pandemic employment levels appear to be disproportionately drawn from low-wage employment that has not returned.

Disproportionate Effects Among Granite Staters

The disproportionate employment impacts of the pandemic on different industries and jobs resulted in uneven impacts across different groups of workers. Nationally, unemployment levels for Black or African American workers, Latino or Hispanic workers, and workers with lower levels of education rose to higher levels and remained elevated for longer than the national average. Estimated levels of long-term unemployment, which is when an individual is unable to find a job for over 27 weeks, remained elevated throughout the second half of 2020 and into 2021, with some of the greatest employment losses occurring among younger workers.[11] Additionally, parents with children, most notably women with younger school-aged children, faced the greatest employment burdens as schools and childcare centers closed for in-person attendance throughout 2020 and early 2021.[12]

Data for New Hampshire shows the COVID-19 crisis resulted in women making up 58.9 percent of workers filing for unemployment assistance during April and May 2020, the initial months of the pandemic’s employment impacts.[13] Other analysis suggests that childcare constraints may be limiting the ability of parents to return to the workforce.[14] Analysis from a New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services-commissioned report found that women and parents with childcare duties faced challenges in returning to work as the capacity for childcare remained below pre-pandemic levels in early 2021. Notably, even pre-pandemic levels of childcare did not meet the levels of need in New Hampshire, with only 60 percent of identified needs met.[15]

Lingering Economic Challenges

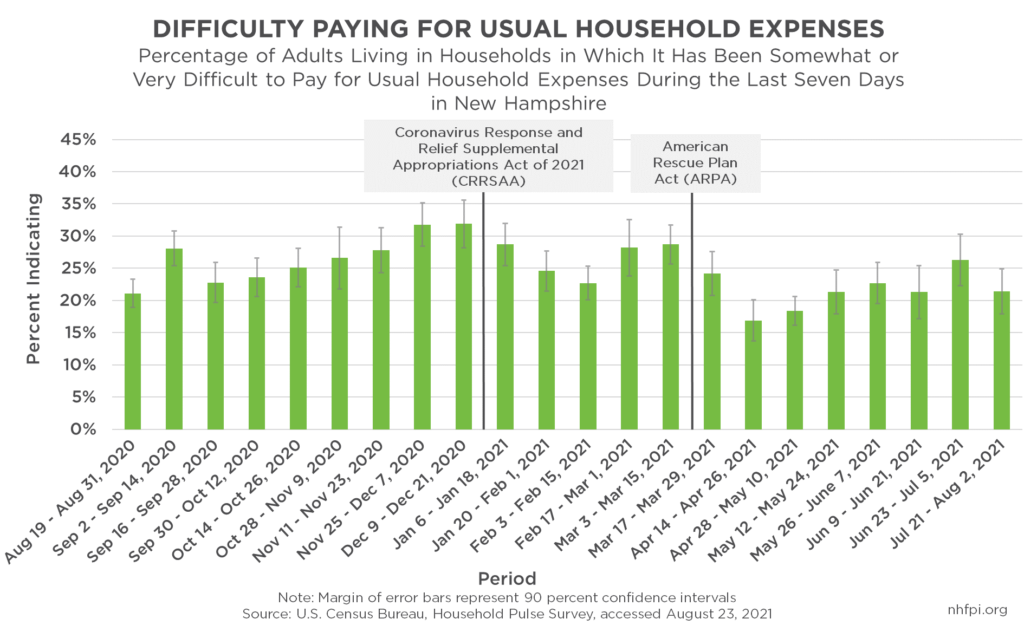

In addition to the overall employment trends across the state economy, continued lingering challenges identified by U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data indicate that many individuals and families continue to face economic hardships. From August 2020 to August 2021, between one in three and one in six households in New Hampshire indicated it had been somewhat or very difficult to afford usual household expenses in the last seven days. Declines in the levels of reported financial challenges are evident immediately after the enactments of two of the recent pandemic-related federal aid packages. These packages included direct economic aid to households and are correlated with temporary declines in the reported difficulties in covering household expenses.[16]

Key Aid and Opportunities for Equitable and Inclusive Investments

During 2020 and early 2021, several federal pandemic-related aid packages provided over $9 billion in support to New Hampshire businesses, non-profits, governments, and individuals and families through key policy actions and direct support.[17] The most recent federal aid package, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) enacted in March 2021, provides several billion dollars in significant targeted assistance, policy changes, and key flexible aid to provide immediate needed support and make strategic, long-term investments in Granite Staters and the economy.[18] In addition to aid targeted towards businesses, governments, and other organizations in the state, there are several key provisions of ARPA targeted at supporting individuals and families in New Hampshire, including:

- Expansions of the Child Tax Credit to up to $3,600 for the youngest children and $3,000 for older children, with a longer age range, full refundability, and payments of the first half of the credit in monthly installments for calendar year 2021 taxes

- Changes to the Earned Income Tax Credit expanding amounts and eligibility for adults without dependents in the household, as well as to older and younger adults, for calendar year 2021 taxes

- Economic Impact Payments, generally $1,400 per person for low- and middle-income households

- An unemployment compensation eligibility expansion to workers who may not be traditionally eligible, including those who are self-employed or working part-time, along with increasing benefits to account for the significant levels of lost wages for many groups of workers (this extended unemployment ended on June 19, 2021 in New Hampshire, while ARPA’s federal policy extends benefits through September 6, 2021 for participating states)

- A 15 percent boost to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, which provides resources to purchase food to individuals and families with low incomes (extended to September 30, 2021)

- Enhanced subsidies for health insurance purchases on the individual marketplace through lowering caps on the amount insurance plans can cost to individuals relative to their incomes, completely subsidizing premiums for low-income individuals and adding a limitation on out-of-pocket costs for many middle-income households

- Emergency rental assistance to prevent and mitigate pandemic-related homelessness, along with support for other tenants, landlords, and homeowners to afford housing expenses

- Boosts in funding for Child Care and Development Block Grant Funds, typically used to subsidize child care for low-income families, with specific provisions to remove income limits on essential worker families receiving child care assistance

In addition to this targeted aid supporting individuals and families, New Hampshire’s state, county, and municipal governments are scheduled to receive a total of $1.457 billion in flexible Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. These funds must be obligated by the end of 2024, and the expenditures must be completed by December 31, 2026. The Interim Final Rule for use and allocation of these funds offers substantial flexibility, with permissible uses to aid the communities and families hit hardest by the pandemic.[19] This interim guidance emphasizes four objectives for the funding:

- “Support urgent COVID-19 response efforts to continue to decrease spread of the virus and bring the pandemic under control”

- “Replace lost public sector revenue to strengthen support for vital public services and help retain jobs”

- “Support immediate economic stabilization for households and businesses”

- “Address systemic public health and economic challenges that have contributed to the inequal impact of the pandemic on certain populations”[20]

The current federal guidance provides for a wide array of uses to directly support a recovery from the COVID-19 crisis with these funds. The federal guidance permits the use of flexible aid dollars to help connect people with public services and to fund public benefit navigators. These navigators would be critical in helping individuals and families, who may have never had to seek public assistance or access benefits and social assistance programs, many of which are new, expanded, or temporary due to pandemic-related legislation.[21] Policymakers within state and local governments have significant latitude to make important investments with these dollars that address the inequities exacerbated by the pandemic. Connecting residents with existing forms of aid would provide critical short-term relief. In addition to investments that provide immediate support and relief, policymakers have opportunities to make critical investments in programs and policies that support all Granite Staters in the long term and strengthen the overall economy as the recovery continues.

Ensuring the investments in the overall economy promote resiliency and recovery, strategic initiatives based on past successful policies are key. During the initial recovery from the Great Recession over a decade ago, analysis and modeling of key policies in the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act by Moody’s Analytics during 2009, when the economy was fairly weak, measured the dollar amount of economic activity generated per a one dollar investment by the federal government. The analysis estimates that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) was the most effective federal economic stimulus examined. SNAP, known in New Hampshire as the Food Stamp Program, generated $1.74 of economic activity for every dollar invested. Extending unemployment insurance benefits generated $1.61, while infrastructure spending generated $1.57.[22] Utilizing the findings about key policies such as these during the recovery from the Great Recession can inform the types of policies that could support the immediate needs of many Granite Staters as well as the overall economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Concluding Discussion

The uneven economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have resulted in disproportionate challenges for certain groups of Granite Staters and the economy overall, with the most severe employment declines having occurred among service-based industries paying lower-than-average wages in New Hampshire. Although many parts of the economy have rebounded relatively quickly, employment in low-wage work continues to fall behind the rest of the recovery. Additionally, overall levels of employment continue to be below pre-pandemic levels, as does the number of individuals participating in the labor force; key challenges like the limited availability of childcare or the threat of adverse health impacts may be keeping people from rejoining the workforce. The trajectory of the ongoing recovery is dependent in part on how public policy directs resources to support the recovery are directed. As the recovery continues, state, county, and municipal governments in New Hampshire have an opportunity to address the economic and employment inequities created and exacerbated by the pandemic. Resources available through the American Rescue Plan Act provide flexibility to respond to the immediate need for support from many workers disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Utilizing flexible Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, policymakers have the next five years to implement strategic policies and collaborative investments that account for local, regional, and statewide needs. These investments will be key to supporting an equitable and inclusive recovery, resulting in a much more resilient and productive economy for all Granite Staters.

Endnotes

[1] More information on seasonally adjusted data is available from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[2] Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Labor Force and Unemployment. Data for 2021 are subject to revision and are not yet benchmarked.

[3] For more information on trends and analyses of the recovery period after the Great Recession, see NHFPI’s August 2019 Issue Brief titled New Hampshire’s Workforce, Wages, and Economic Opportunity.

[4] For additional information, see NHFPI’s blog titled The COVID-19 Crisis After One Year: Economic Impacts and Challenges Facing Granite Staters published on April 9, 2021.

[5] Labor force and other terminology definitions are available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[6] Data published by New Hampshire Employment Security, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, Labor Force and Unemployment. Data for 2021 are subject to revision and are not yet benchmarked.

[7] Additional definitions and concepts related to employment and unemployment are explained by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[8] Additional information on labor force definitions is published by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[9] Data on unemployment claims by industry and other key employment and unemployment data were published weekly during the year following the onset of the pandemic in New Hampshire by New Hampshire Employment Security.

[10] Data compiled and analyzed by Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker; Chetty, Friedman, Hendren, Stepner, and the Opportunity Insights Team, accessed at tracktherecovery.org, a project of Harvard University, Brown University, and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

[11] See the Congressional Research Service’s publication titled Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic, updated August 20, 2021.

[12] Additional information on the groups most impacted during the pandemic, and the challenges in regaining employment faced by women, see the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s report titled COVID-19 economic crisis continues to hurt working mothers the most published April 14, 2021.

[13] See the New Hampshire Women’s Foundation 2020 Special Issue titled The Impacts of COVID-19 on New Hampshire Women published December 2020. Women accounted for 58.9 percent of all overall unemployment in April 2020, with continued disproportionate levels for several months after, when the largest unemployment losses occurred. Additionally, see NHFPI’s September 2020 Issue Brief titled Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[14] See the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis’s report titled Pandemic pushes mothers of young children out of the labor force published February 2, 2021.

[15] For additional information and resources, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services commissioned reported titled Constraints on New Hampshire’s Workforce Recovery: Impacts from COVID-19, Child Care and Benefit Program Design on Household Labor Market Decisions, published by Econsult Solutions Inc. on February 18, 2021.

[16] See the United States Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data tables.

[17] For more information, see NHFPI’s February 2021 presentation titled How Public Services are Funded in New Hampshire.

[18] See NHFPI’s blog titled Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services published on March 26, 2021.

[19] See NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[20] See the United States Department of the Treasury Fact Sheet, published May 2021, on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds.

[21] For more information on the American Rescue Plan Act, the United States Department of Treasury has published a Fact Sheet on March 18, 2021, and an Interim Final Rule related to the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. See also NHFPI’s May 25, 2021 blog Federal Guidance Details Uses of Flexible Aid for State and Local Governments.

[22] For more information on economic multipliers of federal policies in this analysis, see NHFPI’s February 2021 Issue Brief Designing a State Budget to Meet New Hampshire’s Needs During and After the COVID-19 Crisis.