New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program provides health coverage to approximately 50,000 Granite Staters with low incomes. The program is a partnership between the state and federal government that brings hundreds of millions of dollars in federal revenue into the state economy annually, and is key for access to health services for people with substance use disorders or mental health conditions. Health coverage is associated with better health outcomes such as lower mortality, and children are more likely to have health coverage when their parents are covered.

In the most recent reauthorization of the expanded Medicaid program, it was reformed into the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, and work and community engagement requirements were added for enrollees. Certain key categories of enrollees are exempt, but many participants will be required to engage in 100 hours of qualifying work or other activities each month to maintain their health coverage without interruption. As the work requirements are implemented in New Hampshire, research from similar programs in other states and the implementation of work requirements in Arkansas, which led to the disenrollment of more than 18,000 people in 2018, suggest implementing such requirements in New Hampshire risks causing thousands of people with limited means to lose health coverage.

This Issue Brief reviews research on work requirements in other states, discusses the instability of low-wage work, scales estimates of coverage losses from research in other states to New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid population, and summarizes some of the potential reasons for, and effects of, health coverage losses under Medicaid work and community engagement requirements.

Population Impacted by Work Requirements

A variety of policy proposals for work and community engagement requirements exist in different states. New Hampshire, like Arkansas, is implementing these requirements for the expanded Medicaid population, although there are key differences in exemptions for parents and older adults. Certain additional exemptions will apply to specific members of this population as well, and those exemptions vary across states. National research provides indications as to the extent this population is already working, reasons for not working, and the work situations individuals in low-wage jobs commonly face.

Scope of New Hampshire Policy

New Hampshire’s work and community engagement requirements apply to those enrolled in the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, which is New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program and the successor to the New Hampshire Health Protection Program.[1] This program provides health coverage to adults aged 19 to 64 years with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty guideline, which is $17,236 in annual income for an individual and $29,435 for a family of three.[2] Children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, older adults and nursing home residents, and other individuals with low incomes, as well as parents with very low incomes, are eligible for enrollment in the traditional Medicaid program.[3] As of the end of April 2019, 50,291 adults were enrolled in the expanded Medicaid program.[4] The work requirements, which will begin to require reported hours for the month of June, compel expanded Medicaid enrollees to engage in qualifying activities for at least 100 hours per month and report them to the State monthly or risk loss or suspension of coverage. Qualifying activities include:

- Unsubsidized or subsidized employment in the private or public sectors

- On-the-job training

- Job skills training related to employment, with academic credit hours earned from an accredited college or university in New Hampshire, or, in the case of an enrollee who has not received a high school diploma or equivalent, education directly related to employment

- Vocational educational training not to exceed 12 months

- Attendance at secondary school or studies leading to an equivalent certificate for recipients who have not completed secondary school or the equivalent

- Job search or job readiness assistance, including engaging in certain services offered through the New Hampshire Department of Employment Security

- Participation in substance use disorder treatment

- Community service or public service

- Caregiver services for a nondependent relative or other person with a disabling medical or developmental condition

Enrollees exempt from the work requirements include pregnant women, parents or caretakers with dependent children under six years of age or any child with developmental disabilities living with the parent or caretaker (with only one of two parents exempt in a two-parent household), those who do not qualify as able-bodied adults under the federal Social Security Act, and drug court participants. Certain enrollees with a disability or identified as medically frail, those with certification from a recognized health professional of their own or a dependent’s illness or incapacity, and those who are already compliant with the employment initiatives under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families are also exempt. Good cause exemptions and other exemptions, such as for parents with children aged six to 12 years who cannot secure child care, may be applied in certain situations, and specific definitions are dependent on the detailed rules promulgated by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and the federal government’s waiver.[5] These rules include a “curing” process, through which individuals who do not comply with the work and community engagement requirements may make up for missed hours of qualifying activities in the subsequent month.[6]

National Research on Medicaid Enrollees and Work

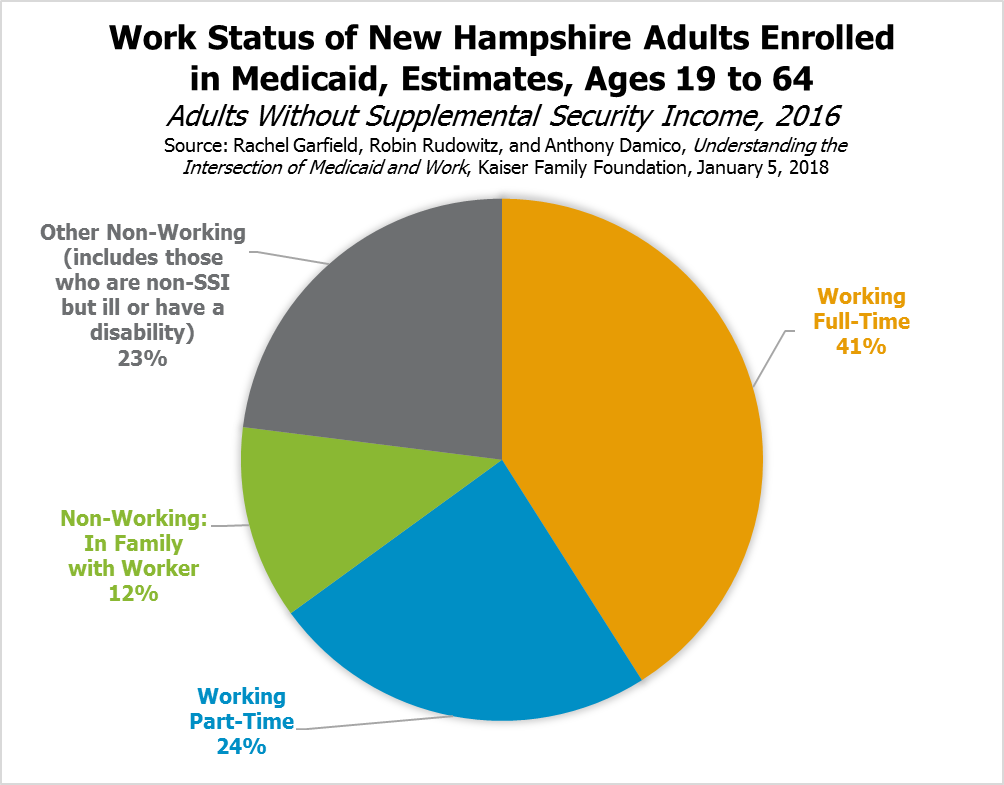

Research indicates many Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide are already working. Research from The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that, in 2016, 60 percent of Medicaid recipients aged 19 to 64 years without Supplemental Security Income (SSI)[7] nationwide, and 65 percent in New Hampshire, were working. The percentage of Medicaid recipients aged 19 to 64 years without SSI in a family with at least one member working was estimated to be 79 percent nationwide and 77 percent in New Hampshire. Of those who were not working, 36 percent nationally and 49 percent in New Hampshire indicated their reason for not doing so was illness or disability, based on survey data. While data for New Hampshire were too limited to be conclusive, 30 percent of those who were not working nationally indicated they were caretaking and 15 percent indicated they were attending school.[8]

Using a different data set, researchers affiliated with The George Washington University found that, among the 2015 U.S. population covered by expanded Medicaid, 48 percent either had a permanent disability, serious mental or physical limitations caused by conditions like cancer, stroke, or mental health disorders, or were in fair or poor health. Of the remaining portion covered by expanded Medicaid, all but one quarter were working, seeking work, or in school. In total, 87 percent were either in the roughly half of beneficiaries who might not be considered “able-bodied” or were in school, working, or seeking work. Of the remaining 13 percent, three in four reported not working to care for family members.[9]

The authors also separately concluded that non-working Medicaid beneficiaries potentially subject to previously-proposed national work requirements need more health care than those who are working, with higher rates of hospitalizations and doctor visits and three times the likelihood of already-working enrollees to have seen a mental health professional in the past year. Those at risk of losing Medicaid were about 63 percent women, 39 percent adults aged 45 to 64 years, and about half racial and ethnic minorities.[10]

Irregular Work Hours and Employment Turnover

The population enrolled in expanded Medicaid may be more likely to work low-wage or seasonal jobs and experience unstable or unpredictable work hours. These work hours may change substantially on a weekly basis; about 55 percent of respondents to a 2014 survey indicated their hours varied from week to week. In food services or production and retail or wholesale trade, 71 percent and 63 percent, respectively, of respondents reported weekly variability.[11]

Additionally, low-wage labor market volatility means individuals might hold multiple jobs in a short period of time, or enter and exit the labor force frequently. National survey data collected between 2016 and 2018 show about one in five workers aged 18 to 59 years and without children switched between working more than 20 hours per week, less than 20 hours per week, seeking employment, or being out of the labor force during that period. Separate survey data from 2013 and 2014 showed that Medicaid enrollees aged 18 to 64 years in the labor force most commonly cited employment-related reasons for not working, such as not being able to find work or being laid off, while those out of the labor force most commonly cited health- or disability-related reasons, particularly those aged 50 to 64 years.[12]

In New Hampshire, retail trade remains the largest sector for employment, at approximately 95,500 employees in March 2019, with accommodation and food services totaling 61,500 employees.[13] The accommodation and food services sector nationwide saw the instances of people leaving their jobs total 74.9 percent of annual average employment during 2018, compared to a rate of 44.3 percent for all jobs, suggesting considerably higher turnover in the sector; the retail sector saw a rate of 58.3 percent.[14] Food service workers also had the lowest median tenure of any job, based on September 2018 research from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.[15] Both weekly hour and job tenure volatility in these two important employment sectors suggests that New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid population may have difficulty consistently meeting work requirements even with substantial engagement in the labor force.

Research specifically focused on volatility of work hours and employment in low-wage positions relative to Kentucky’s work requirement estimated that close to half of all low-income workers who could be affected by a Medicaid work requirement policy like Kentucky’s would be at risk of losing coverage for one or more months. The study finds that even for those working 1,000 hours per year, which averages about 83 hours per month, about one quarter of the population could be at risk of losing coverage because they did not meet the work requirement every month.[16]

Evidence from Other States and Existing Research on Coverage Losses

Fifteen states have applied for or obtained approval for waivers from the federal government that would require individuals comply with work and community engagement requirement activities to access coverage. Only Arkansas has fully implemented a work or community engagement requirement and disenrolled individuals for not reporting sufficient hours. Notably, implementation of the work requirements in Arkansas and Kentucky have been halted by court decisions; the legality of both the process around approval of the requirements in these two states and the requirements themselves under the federal Medicaid statute continue to be considered.[17] Although the court decisions have only halted work requirement implementation in these two states, questions remain around whether work and community engagement requirements themselves are legal, as the federal Medicaid statute’s purpose is to furnish medical assistance to individuals whose resources cannot pay the costs of needed medical services and provide rehabilitation or other services to help individuals reach or retain capability for independence or self-care. Evidence suggests work requirements may result in the loss of such assistance and services.[18]

The Arkansas requirement was implemented during 2018, and 18,164 individuals were disenrolled by the end of the year due to failure to meet the work and community engagement requirement. Only 1,910 (11 percent) of those disenrolled have reapplied and regained Medicaid coverage in 2019, as was permitted under the law, as of the end of February. As of March 7, 2019, 7,066 enrollees had one month of noncompliance recorded for the calendar year, and 6,472 had two months.[19]

Arkansas’s requirements differ in key ways from New Hampshire’s requirements. Arkansas initially required use of an online portal for reporting compliance and also requires disenrolled individuals to wait until a subsequent calendar year to reapply for health care coverage. New Hampshire permits reporting through other methods as well as through an online portal. However, Arkansas requires 80 hours per month of qualifying activities, does not require those with children under 18 years old to work, has been phasing in the requirements for different groups within the Medicaid expansion population (starting with 30-to-49 year old enrollees in poverty), and currently has automatic cross-verification with other programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, that exempts individuals from needing to report for Medicaid. New Hampshire requires 100 hours of qualifying activities, requires enrolled parents with children age 6 and older to work unless they have a child care exemption and a child under 13 years old, will be implemented for adults aged 19 to 64 years, and does not have an automatic cross-verification program in place. During the early months of implementation in Arkansas, the data matching within State data sets led to the automatic exemption of about two-thirds of enrollees from reporting requirements. About three in four individuals required to report hours personally failed to do so each month.[20] Automatic verification appears to be critical for keeping people who are found eligible in the program, particularly in the early days of implementation.

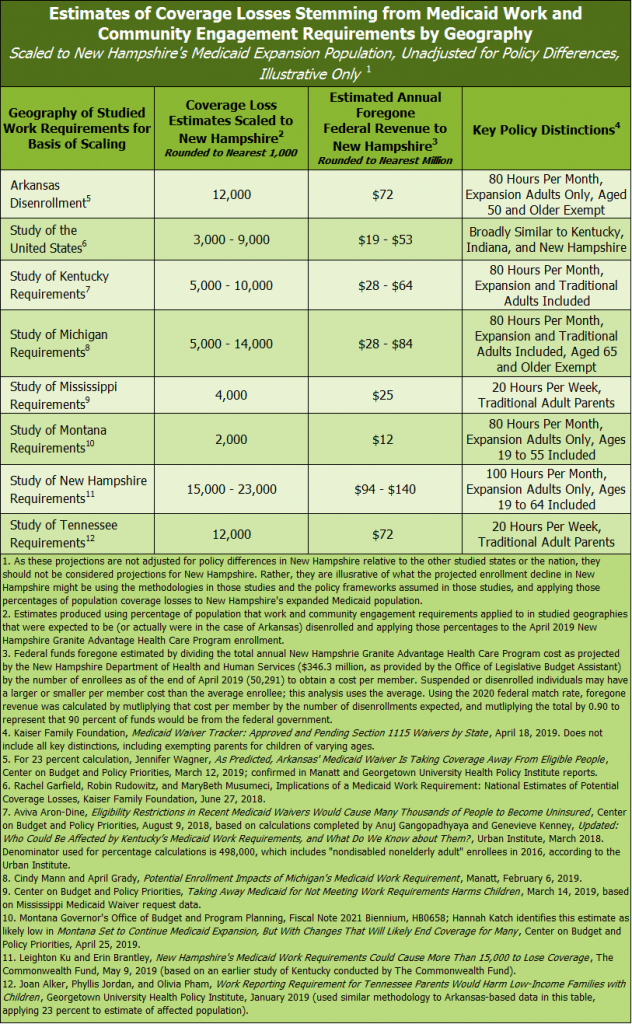

Differences in the details of these programs, and the method of implementation, can have a profound impact on the ability of individuals to remain enrolled. Nevertheless, available research indicates a risk of coverage losses following the implementation of work requirements. The experience in Arkansas and studies from other states inform what might happen in New Hampshire. In its July 2018 Medicaid waiver application, the State of New Hampshire estimated that enrollment in the program would not change materially and would remain near current levels, but provided several examples of factors that could change enrollment and did not have the benefit of disenrollment data from Arkansas and subsequent research at the time of that estimation.[21] While the details of the implementation and the dynamics of the population may be significantly different in other geographies, no existing quantitative research identified indicates New Hampshire would not experience enrollment declines or is not at significant risk of suspending thousands of people from health coverage by implementing Medicaid work requirements.[22]

Medicaid is a fiscal partnership between the federal government and state governments to defray the costs of health coverage for people with low incomes. For most aspects of the program, the federal government provides a dollar-for-dollar match to funding provided at the state-level, funding 50 percent of Medicaid costs. The federal match is more favorable to states within the expanded Medicaid program. The federal government will fund 90 percent of the cost of expanded Medicaid enrollees starting in 2020 and every following year, and is funding 93 percent of enrollee coverage costs in 2019. As such, coverage losses would lead to fewer federal dollars contributing to the New Hampshire economy and funding health care services for low-income people in the state.[23]

While there are important differences in these policies across states, scaling all these different research efforts identified in the table above to New Hampshire shows substantial coverage losses. These scenarios vary considerably, but all suggest people will lose health coverage as a result of the work and community engagement requirements.

Communication and Implementation Challenges

Communicating complex changes to public policy can be challenging. Many expanded Medicaid enrollees may be experiencing financial or other chronic stresses. Experiences in Arkansas suggest that both contacting and informing the expanded Medicaid population can be difficult, and many individuals appeared to be unaware of the work and community engagement requirements.[24] Enrollees who were aware of the new requirements were often confused by the complexity of the new program, including the key rules to maintain coverage and the reporting required.[25] Although the State of Arkansas had conducted outreach through mailings, phone calls, texts, online videos, and emails, people who were working sufficient hours to fulfill the requirement may have lost coverage because of a lack of understanding or information about the requirements.[26]

The communication and implementation challenges experienced in Arkansas led the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, a federal nonpartisan legislative agency that provides analysis and makes recommendations to Congress and other organizations, to recommend pausing disenrollments to establish effective evaluation and monitoring mechanisms before states enforce work requirements that might lead to disenrollments.[27]

Potential Effects of Coverage Losses on Individuals

Losing access to health coverage may increase the risk that individuals face serious health-related challenges. Evidence suggests that having health coverage reduces mortality, makes individuals more likely to access health services or to not delay treatment, increases the likelihood of seeking preventative treatment, and reduces the probability that individuals have difficulty accessing care.[28] Expanded Medicaid coverage is also important for increasing the access to health care services for low-income people struggling with substance use disorders or mental health conditions.[29]

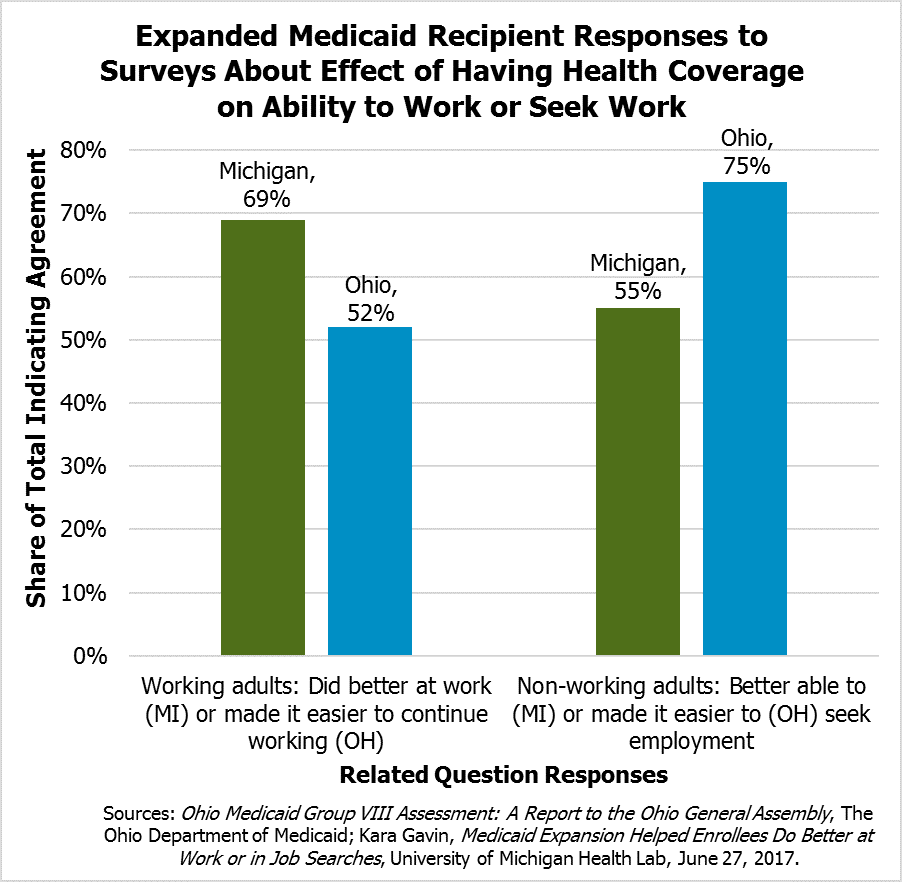

Losing coverage may also produce negative effects on employment.[30] Independent research from the Ohio Department of Medicaid and the University of Michigan found that majorities of surveyed expanded Medicaid enrollees who were working in Ohio (52 percent) and Michigan (69 percent) said having health coverage made it easier for them to continue working or made them better at their jobs. Of those who were not working, majorities in Ohio (75 percent) and Michigan (55 percent) indicated that health coverage made the process of looking for a job easier or made them better able to look for a job.[31]

Limited Insurance Options through Employers

Disenrolled individuals may have difficulty finding employer-sponsored health insurance if they lose expanded Medicaid coverage, as many low-wage jobs do not offer employer sponsored coverage or the associated premiums may be too expensive for workers with low wages to afford. An analysis of national labor statistics from 2017 showed that for workers with earnings in the bottom quarter of the wage distribution, only approximately 37 percent were offered health coverage by their employer, and fewer obtain coverage.[32] Disenrolled individuals in Arkansas reported not having access to or being able to afford employee-sponsored health insurance.[33]

An analysis of New Hampshire firms showed that expanded Medicaid enrollees who lose coverage would have limited options for employee-sponsored coverage. About four in every five full-time employees at private sector firms were eligible for health insurance in 2017, but the proportion of part-time employees eligible was less than one in ten. For small firms with less than 50 employees, the proportion of full-time employees eligible for employee-sponsored insurance dropped to approximately 55 percent, and part-time employees remained unlikely to be offered employer-sponsored coverage. The average annual employee contribution for a single coverage plan was $1,649, which is 12.5 percent of the annual income of a 35 hour-per-week worker making minimum wage in New Hampshire and a higher percentage for workers who are employed fewer hours.[34] Similar research from Kentucky suggests that employees at small businesses or firms predominantly offering lower wages are less likely to find insurance through their employment.[35]

Impacts on Children

Although expanded Medicaid does not cover anyone under 19 years of age directly, existing research provides significant evidence that children of parents without coverage are less likely to be insured themselves. March 2017 data show that only 0.9 percent of children of insured parents were uninsured, while 21.6 percent of children with uninsured parents were uninsured.[36] Parents near to poverty and enrolled in Medicaid are also much more likely to have their children receive well-child visits than those not enrolled in Medicaid, and the expansion of Medicaid to adults in certain states between 2013 and 2015 appeared to increase the enrollment of previously-unenrolled children.[37]

When adults lose access to health care, children may be less likely to be insured, and family financial stability is put at greater risk. Uninsured children with common childhood illnesses or injuries are less likely to receive the same level of care as insured children, are at higher risk for preventable hospitalizations, and may be more likely miss diagnoses of serious health conditions.[38] Some research also suggests children who have access to public health coverage are more likely to graduate from high school and college and pay more in taxes later in life.[39]

Concluding Discussions

The New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program uses federal and state funds to provide health coverage to about 50,000 adults with low incomes in New Hampshire, and is key to accessing services for people with substance use disorders and mental health conditions. Available evidence suggests that many individuals enrolled in the program are at significant risk of losing health coverage with the implementation of work and community engagement requirements in the state. While New Hampshire’s situation may be unique in some respects, no quantitative projections of coverage losses in other states provide indications that coverage losses will not occur in New Hampshire, and the disenrollment of over 18,000 expanded Medicaid recipients in Arkansas provides a warning of both the risks of implementation issues and imposing work requirements themselves. While the calculations provided in this Issue Brief are not tailored to New Hampshire’s policies and are based on existing external research, they provide a clear indication that the direction of the effects of work requirements is toward coverage losses.

Workers with low incomes may have irregular work hours or more job transitions relative to the population as a whole. These individuals and others, such as those with substance use disorders or mental health conditions, may face particular difficulty in meeting work and community engagement requirements regularly despite being engaged in the workforce. The details of the applicability and implementation of exemptions and the required timeframes for fulfilling work requirements matter considerably to whether these individuals retain continuous health coverage. Suspension or disenrollment increases the risk to the health of individuals, may risk health coverage for the children of those individuals, and may also diminish an individual’s ability to participate fully in the workforce.

Endnotes

[1] To read more about the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes. See also NHFPI’s May 2018 Common Cents post Senate Approves Medicaid Expansion Bill as Amended by the House.

[2] See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2019.

[3] For more information on the Medicaid program in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes and the associated citations, specifically in endnote 2.

[4] Data collected from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Caseload Statistics Report, April 30, 2019.

[5] To see the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program Medicaid Waiver and associated documents, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Granite Advantage Health Care Program Section 1115(a) Demonstration Waiver.

[6] For more details on all the specific exemptions, qualifying activities, good cause exemptions, and the curing process, see the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Granite Advantage Health Care Program.

[7] Supplemental Security Income is designed to help elderly, blind, or disabled people with little or no income. See the U.S. Social Security Administration, Supplemental Security Income Home Page for more information.

[8] For more information and percentages of Medicaid recipients working nationally and in other states in 2016, see Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Anthony Damico, Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 5, 2018, with associated state-by-state tables and details.

[9] For more information, see Leighton Ku and Erin Brantley, Myths About The Medicaid Expansion And The ‘Able-Bodied’, Health Affairs Blog, March 6, 2017.

[10] For more information, see Leighton Ku and Erin Brantley, Medicaid Work Requirements: Who’s At Risk?, Health Affairs Blog, April 12, 2017.

[11] For the survey results for other industries and the associated full report, see Lonnie Golden, Still Falling Short on Hours and Pay, Economic Policy Institute, December 5, 2016.

[12] For more information, see Lauren Bauer, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Jay Shambaugh, Work Requirements and Safety Net Programs, The Hamilton Project (The Brookings Institution), October 2018.

[13] For detailed tables, see New Hampshire Employment Security, New Hampshire Economic Conditions: Housing in New Hampshire – 2017, May 2019.

[14] For detailed tables by industry and year, see the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic News Release Table 16, Annual total separations rates by industry and region, not seasonally adjusted.

[15] For the full report, see the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employee Tenure in 2018, September 20, 2018.

[16] For the full study, see Aviva Aron-Dine, Raheem Chaudhry, and Matt Broaddus, Many Working People Could Lose Health Coverage Due to Medicaid Work Requirements, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 11, 2018.

[17] Counts of states as of April 18, 2019. To track Medicaid work and community engagement requirement waivers, see the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State.

[18] For the two most recent court decisions related to Kentucky and Arkansas, see U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Stewart v. Azar, Civil Action No. 18-152 (JEB), March 27, 2019 and U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Gresham v. Azar, Civil Action No. 18-1900 (JEB), March 27, 2019. For more on the relationship between work and community engagement requirements and health effects, see Larisa Antonisse and Rachel Garfield, The Relationship Between Work and Health: Findings from a Literature Review, Kaiser Family Foundation, August 7, 2018. See also Philip Rocco, Why Work Requirements Will Not Improve Medicaid, Scholars Strategy Network, April 19, 2018. For more information, see MaryBeth Musumeci, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, Medicaid and Work Requirements: New Guidance, State Waiver Details and Key Issues, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 16, 2018 and Henry J. Aaron, Medicaid job requirements would hurt America’s most vulnerable, 5 on 45, Brookings Institution, January 17, 2018.

[19] For data from Arkansas related to enrollment and disenrollment, see the Arkansas Department of Human Services, ARWorks Reports. For more information and analysis of these figures, see Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Cornelia Hall, February State Data for Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas, March 25, 2019.

[20] For more information on the initial implementation of the work requirements in Arkansas, see MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Cornelia Hall, An Early Look at Implementation of Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas, Kaiser Family Foundation, October 8, 2018. See also Jennifer Wagner, As Predicted, Arkansas’ Medicaid Waiver Is Taking Coverage Away From Eligible People, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 12, 2019 and Jessica Greene, Early Lessons from Arkansas and Indiana’s Very Different Medicaid Work Requirement Policies and Implementations, Health Affairs blog, March 7, 2019.

[21] To see New Hampshire’s Medicaid waiver application, see the Granite Advantage 1115 Waiver Amendment and Extension Application, July 23, 2018. Arkansas did not project disenrollments in its waiver application; see Seema Verma, Letter to Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson and Waiver Approval Documentation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 5, 2018.

[22] Relative to descriptions of New Hampshire, suspension and disenrollment are both used to signify a loss of coverage. New Hampshire’s program suspends those who do not meet the work and community engagement requirements, rather than immediately disenrolling them.

[23] For more information on federal funding of Medicaid, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes and NHFPI’s September 25, 2017 Common Cents blog post Medicaid Block Grant Proposals Would Significantly Reduce Funding for New Hampshire.

[24] See Harrison Neuert, Eleni Fischer, Matthew Darling, and Anthony Barrows, Work Requirements Don’t Work: A Behavioral Science Perspective, ideas42, March 2019.

[25] For documentation of the experiences and difficulties enrollees in Arkansas faces, see MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and Perspectives of Enrollees, Kaiser Family Foundation, December 18, 2018.

[26] For more analysis, see Judith Solomon, Medicaid Work Requirements Can’t Be Fixed, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 10, 2019.

[27] The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) presented their recommendations in a letter to U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar II. That November 8, 2018 letter is available on the MACPAC website. For more information on the Commission, see About MACPAC.

[28] For more details and summaries of existing relevant research, see Steffie Woolhandler and David U. Himmelstein, The Relationship of Health Insurance and Mortality: Is Lack of Insurance Deadly?, Annals of Internal Medicine, September 19, 2017 and Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2019.

[29] For summaries of the concerns associated with work and community engagement requirements and these populations, see two briefs and associated citations from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms People With Substance Use Disorders and Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms People with Mental Health Conditions.

[30] For more on work and health, see Larisa Antonisse and Rachel Garfield, The Relationship Between Work and Health: Findings from a Literature Review, Kaiser Family Foundation, August 7, 2018. See also Philip Rocco, Why Work Requirements Will Not Improve Medicaid, Scholars Strategy Network, April 19, 2018.

[31] For survey details, see Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the Ohio General Assembly, The Ohio Department of Medicaid and Kara Gavin, Medicaid Expansion Helped Enrollees Do Better at Work or in Job Searches, University of Michigan Health Lab, June 27, 2017. See also Judith Solomon, Medicaid Work Requirements Can’t Be Fixed, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 10, 2019.

[32] For a summary of this analysis, see Judith Solomon, Medicaid Work Requirements Can’t Be Fixed, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 10, 2019.

[33] See MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and Perspectives of Enrollees, Kaiser Family Foundation, December 18, 2018.

[34] For the full analysis and references, see Emily M. Johnston, Anuj Gangopadhyaya, Genevieve Kenney, and Stephen Zuckerman, New Hampshire Residents Who Lose Medicaid Under Work Requirements Will Likely Face Limited Employer-Sponsored Insurance Options, Urban Institute, May 13, 2019.

[35] For the analysis of Kentucky employer-sponsored insurance, see Anuj Gangopadhyaya, Emily Johnston, Genevieve Kenney, and Stephen Zukerman, Kentucky Medicaid Work Requirements: What Are the Coverage Risks for Working Enrollees?, Urban Institute, August 14, 2018.

[36] For details, the Michael Karpman and Genevieve M. Kenney, QuickTake: Health Insurance Coverage for Children and Parents: Changes between 2013 and 2017, Urban Institute, September 7, 2017.

[37] For more details and an overview of related studies, see Karina Wagnerman, Research Update: How Medicaid Coverage for Parents Benefits Children, Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, January 12, 2018.

[38] For details and additional citations, see Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2019.

[39] For more information and supporting citations, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms Children, March 14, 2019. See also Joan Alker and Olivia Pham, Work Reporting Requirement for Tennessee Parents Would Harm Low-Income Families with Children, Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, January 30, 2019.