Traditional economic theory postulates that when supply is low and demand is high, prices increase. As the supply of a good or service increases to become readily available relative to the demand for it, prices begin to decrease. The child care industry, however, does not function as traditional economic theory would suggest. In New Hampshire and elsewhere, there is currently a high demand for child care services slots, and a low supply of availability. This occurrence dictates a higher price for a product or service, but the current child care business model cannot charge the true cost of providing high-quality care. Programs cannot raise prices high enough to cover the costs of providing their crucial services and still have enough families who can afford to purchase those services. The result of these fragile economics is that parents pay high prices for tuition, but child care programs typically make little or no profit, while early childhood educators make low wages. Consequently, efforts to increase supply may not be economically feasible for child care businesses, as it would require increasing tuition prices and decrease early childhood educator wages, or to run unsustainable budget deficits. The fragile economics of the child care sector contribute to these businesses being at an elevated risk for closures.

High Prices for Families

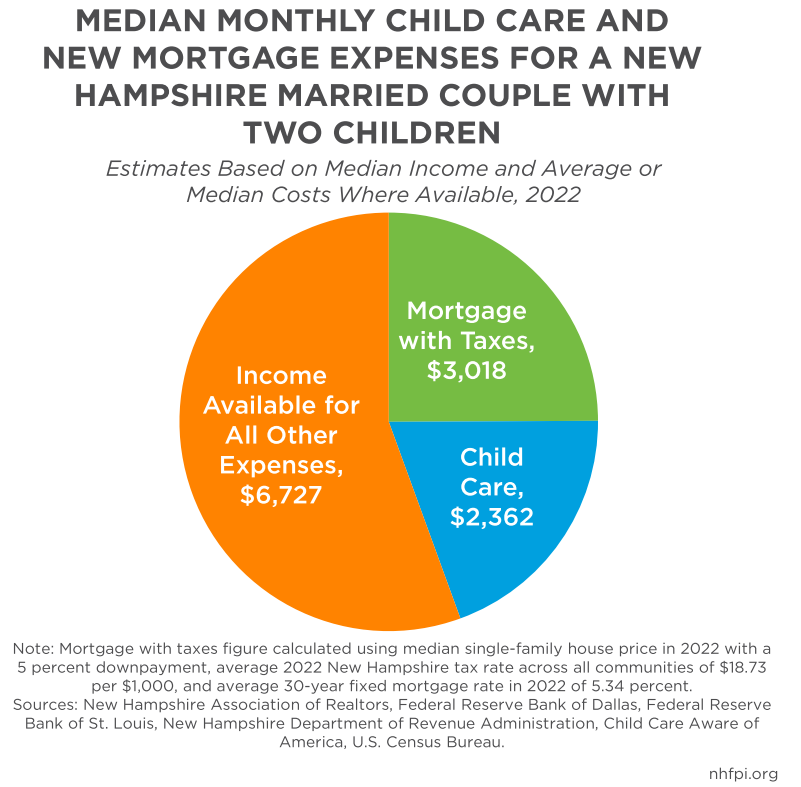

The average annual price for an infant and four-year-old child in center-based care in New Hampshire was $31,868 in 2023, a 12.5 percent increase from $28,340 in 2022. When child care prices are paired with New Hampshire’s record-breaking house sale prices and high mortgage interest rates, families may need to devote a sizable portion of their household income toward child care and housing expenses. For example, a median income married couple family with children earned $145,289 annually ($12,107 monthly) in 2022. If this couple had two children under four in center-based child care, the 2022 estimates suggest they paid, on average, $2,362 monthly for child care. If this family purchased a median-priced single-family house in 2022, they would have a monthly mortgage of $3,018 (including property taxes). Altogether, this family would have spent 44 percent of their monthly household income on mortgage and child care payments alone, leaving only 56 percent ($6,727) for all other expenses including food, transportation, and health care.

Low Wages and High Turnover for Child Care Workers

Although tuition for child care is beyond the federal government’s affordability benchmark for many families in the Granite State, most child care programs are not charging families the “true cost of care.” True cost of care for child care providers encompasses all traditional business expenses as well as those necessary to provide a stimulating environment and curriculum for children and families, meet licensing requirements, create profit margins similar to those of other small businesses, and pay child care workers professional wages. Child care programs can only charge tuition rates that local families can afford, and as a result, child care workers are often paid based on the amount that remains after paying other required expenses.

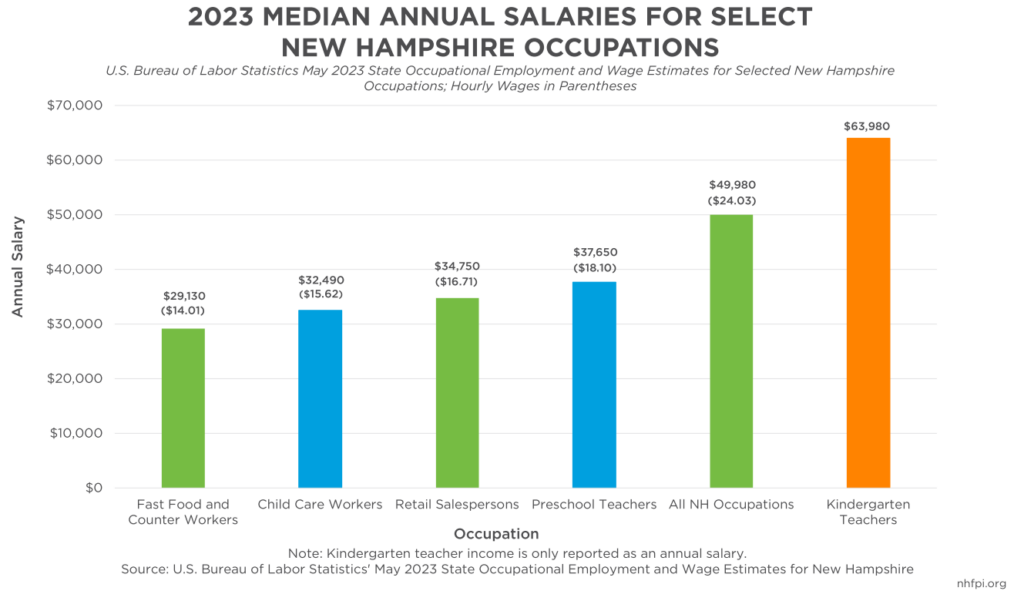

In 2023, the median hourly wage for a New Hampshire child care worker was $15.62 an hour. This equates to $32,490 annually, only $2,500 more than the 2023 federal poverty guideline for a family of four, and approximately half of the 2023 median salary for New Hampshire’s kindergarten teachers. New Hampshire’s preschool teachers earned a median annual salary of $37,650 in 2023, which is approximately $12,000 less than the median annual salary and wage income of all New Hampshire occupations. New Hampshire’s child care services are mostly provided by women, with an approximate 10 to 1 ratio in the field during the first three quarters of 2023. Because the child care workforce is composed of mostly women, the low wages associated with roles in this profession exacerbate existing income inequities for women in the Granite State.

As one-time federal funding to New Hampshire’s early childhood care and education sector ends in September 2024, the industry will likely need additional investment to remain stabilized due to the fragile nature of the child care economy. Without investments to address supply challenges, families may struggle to access quality child care for their children. These challenges extend to the entirety of the Granite State as individuals, limiting their ability to contribute to a more vibrant New Hampshire economy.

For more analysis and citations, see NHFPI’s May 2024 Issue Brief: The Fragile Economics of the Child Care Sector.