The next New Hampshire State Budget will fund public services at a critical time in the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. New Hampshire’s residents and the economy overall will be vulnerable both to ongoing threats to public health and to the financial hardship endured since the pandemic struck the state in March 2020. Household finances for many residents, including those entering the crisis with the fewest resources, have been severely impacted by the pandemic. While federal aid and state policy have provided critical help, continued support will be necessary to mitigate public health risks, help meet the needs of Granite Staters, and provide support to the economic recovery.

Existing research suggests policies that deploy resources directly to low-income residents, as well as those that support public services, employment, and infrastructure, are the most effective at stimulating economic growth. Other policies, such as permanent tax reductions, appear to have a more limited impact, and timing of policies can also alter their value. Policymakers have flexibility to deploy resources to maximize the positive impacts of services across the State Budget biennium, and also have the opportunity to maximize the effectiveness of State resources and any flexible federal aid to support Granite Staters and the economic recovery. These policy choices can help build an equitable, sustainable, and inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

More Acute Needs Earlier in the Budget Biennium

The COVID-19 crisis created swift and massive shocks to health and service delivery systems, the finances of many households, and the economy overall. With nearly 166,000 fewer Granite Staters working in mid-April 2020 than in mid-February 2020, a 22 percent reduction in total employment, many households saw their finances thrown into disarray.[i] Simultaneously, health care systems were strained by the introduction of a new, easily transmissible, and difficult-to-track virus, rendering congregate living settings and home health visits suddenly riskier for both patients and caregivers.[ii]

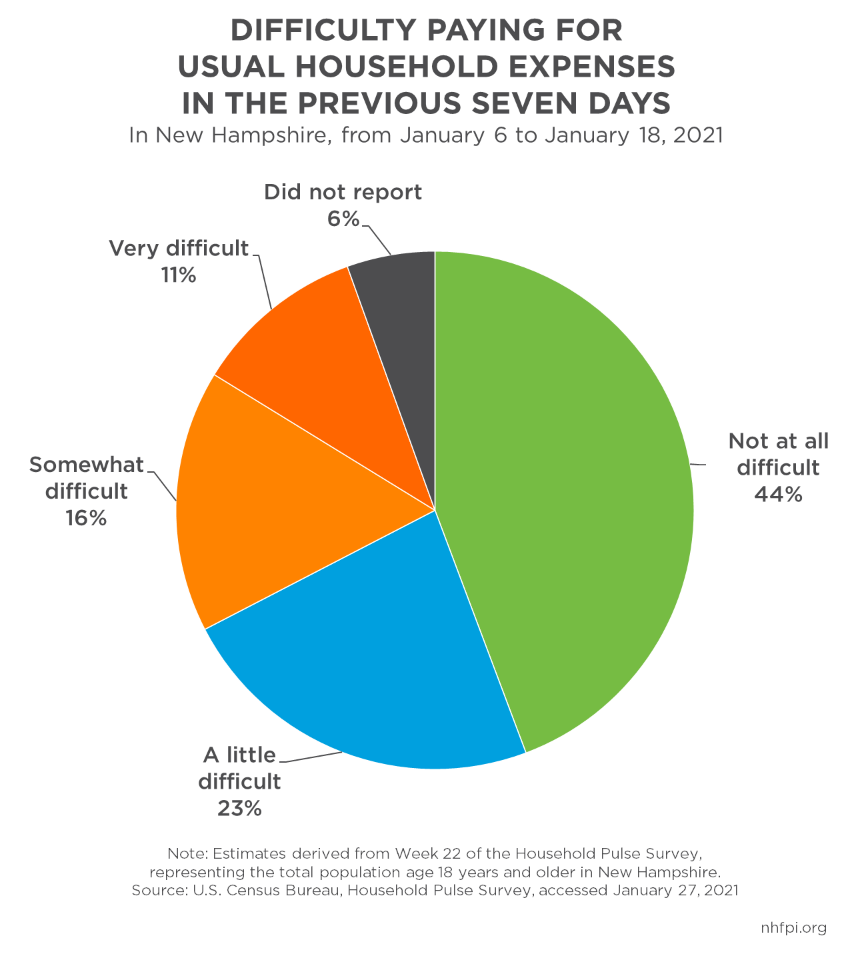

While there has been some considerable recovery in the state’s economic conditions as society and governments have adapted to the ongoing public health crisis, many New Hampshire residents still face substantial challenges to affording basic expenses.[iii] Significant federal support for residents and the economy has provided critical relief, especially in the middle of 2020, but has not alleviated hardship in a complete or sustained manner. U.S. Census Bureau data indicate that, in early January 2021 and well after the most severe employment impacts during the COVID-19 crisis, more than one in four Granite Staters reported it was somewhat or very difficult to pay for usual household expenses. Nearly half of New Hampshire households reported a loss of employment income between mid-March and mid-July of 2020, and both food and housing insecurity have been elevated due to the pandemic.[iv]

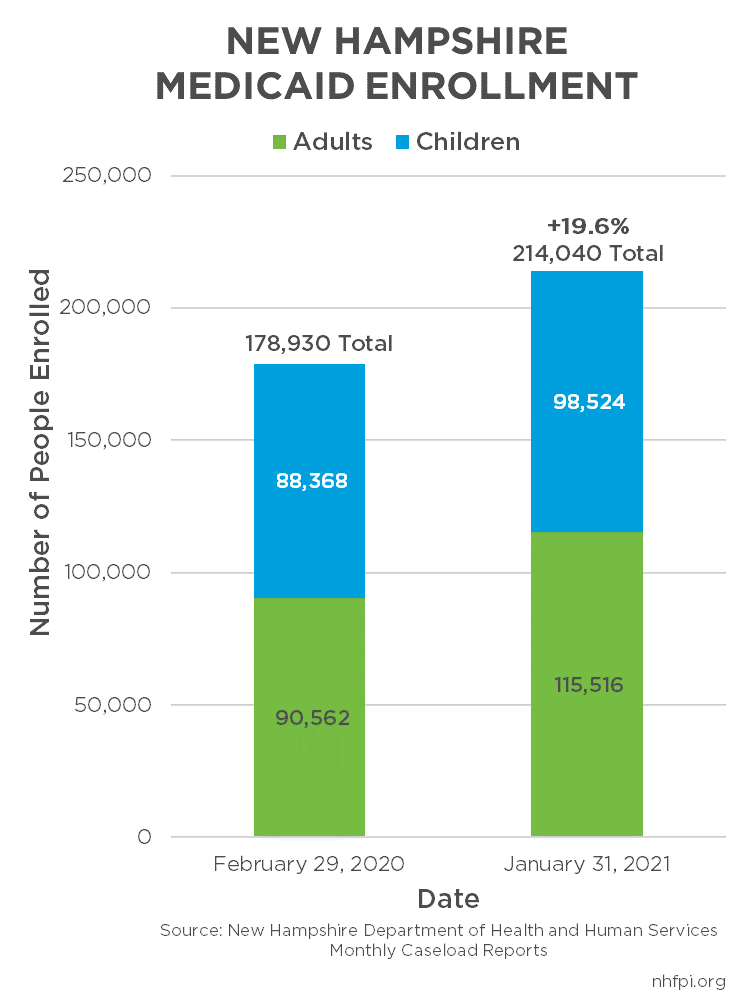

Systems designed to support residents have been strained during the pandemic as well, particularly relative to the provision of health care and social services. The number of residents relying on Medicaid, a federal and state program designed to provide health coverage to people with low incomes or limited assets, has increased by nearly 20 percent in New Hampshire between the end of February 2020 to the end of January 2021. More than 214,000 residents were enrolled in Medicaid on January 31, 2021.[v] Prior to the pandemic, key sectors of the health care service delivery system, particularly for services delivered through Medicaid, had difficulty finding workers to fill needed positions. Services delivered with Medicaid payments included home health care and community-based services for older adults and people with disabilities, nursing home care for people with limited incomes and assets, and health coverage and services for adults and children with low incomes; these are populations that have likely been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 crisis.[vi] Tens of thousands of Granite Staters suffering from substance use disorders or with mental health concerns also access care through Medicaid, and the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated health risks for these individuals as well.[vii]

The low values of many Medicaid reimbursement rates, which are payments to providers for services and are funded primarily through the New Hampshire State Budget and federal matching funds, likely contributed to this workforce shortage prior to the COVID-19 crisis.[viii] Health care workforce shortages have been exacerbated by the pandemic.[ix] With more Granite Staters relying on Medicaid and overall workforce participation lower due to the pandemic, maintaining or bolstering Medicaid reimbursement rates will likely become more critical to help ensure successful and safe delivery of medical and care services to vulnerable residents, particularly earlier in the recovery and the State Budget biennium.[x]

The needs for both service system and broader economic supports are likely to be more acute earlier in the biennium. With the public health crisis anticipated to recede as more people are vaccinated, individuals and families will be able to begin engaging in economic activity that had previously been unsafe. The recovery may be slower than desired, however, particularly for people who went into the COVID-19 crisis with low incomes and limited resources; these residents had the least ability to weather this storm. Lower-income households were more likely to experience losses in employment income during the worst period of the pandemic than households with higher incomes.[xi] The needs of these Granite Staters, along with the overall economic benefits resulting from spending on services and infrastructure, will likely be greatest at the beginning of the State Budget biennium and may decline as the recovery continues.

During the economic recovery from the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, wages at the lower end of the income spectrum fell the furthest behind the rate of inflation among wages in New Hampshire; these lower wages also took the longest time to recover to inflation-adjusted levels from before the Great Recession.[xii] As the COVID-19 crisis has disproportionately harmed the finances of people working in lower wage sectors, these workers and families will likely face the steepest climb to recover from the impacts of the crisis.[xiii] Granite Staters who faced severe health impacts, children who had more challenges to being able to successfully participate in remote schooling, and families who became less housing and food secure are likely to be in need of additional supports as well.[xiv] Providing assistance and boosting the economic security of these individuals and families earlier in the recovery will help the entire economy grow more quickly.

Public Policy and the Recovery

Policy decisions by local, state, and federal governments can have a substantial impact on the economy. Key decisions following the Great Recession and during the COVID-19 crisis had important effects on the health of the economy and the residents who participate in it.

Returns on Policy Investments: Evidence from the Great Recession and Recovery

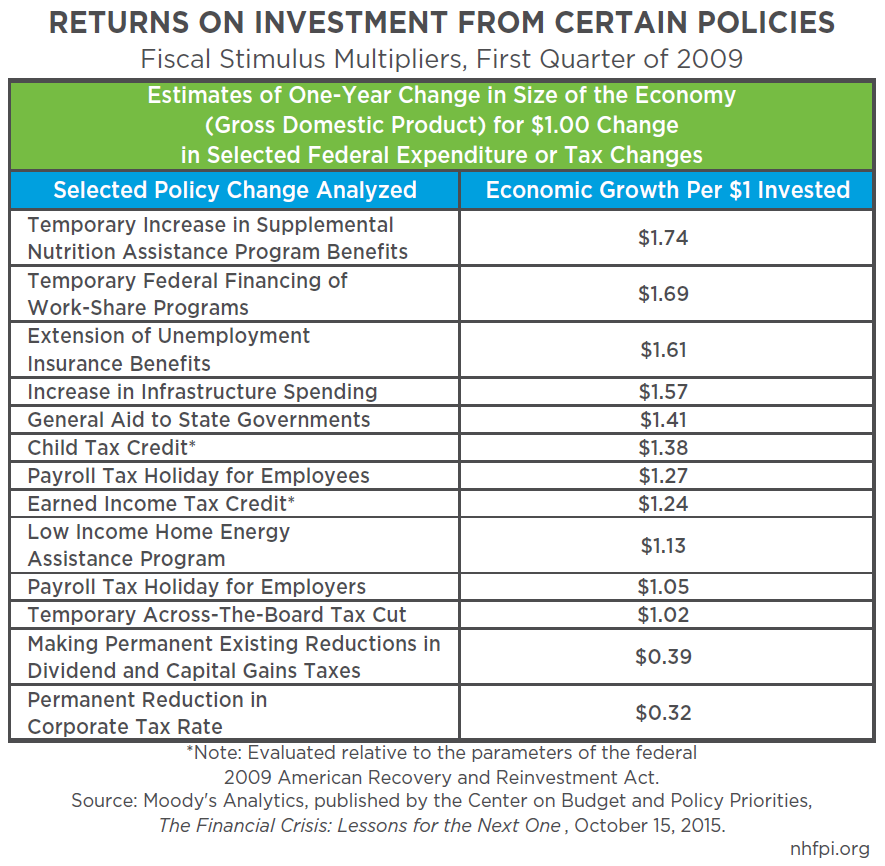

During the Great Recession and the subsequent recovery, researchers examined federal policies designed to stimulate economic growth and help people through financially difficult times. Moody’s Analytics evaluated federal policies in the context of the economic conditions in early 2009, close to the nadir of the Great Recession, based on their abilities to stimulate economic growth. The analysis evaluated these policies for their impact on the size of the economy for every one dollar in additional expenditures or in forgone revenue.[xv]

Moody’s Analytics found that temporary additional Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, which are delivered through the Food Stamp Program in New Hampshire, generated $1.74 of overall economic activity for every $1.00 invested in that year.[xvi] This policy was the most effective stimulus of any analyzed in the study, and was followed by temporary federal financing of work-share programs ($1.69), extending unemployment benefits ($1.61), and increasing infrastructure spending ($1.57). General aid from the federal government to state and local governments was estimated to generate $1.41 per federal dollar invested.[xvii]

The expansion of the Child Tax Credit under the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), primarily benefitting low-income families with children, was the most stimulative tax reduction, with a multiplier of $1.38 per new dollar invested.[xviii] A permanent reduction in taxes on dividends and capital gains was projected to add $0.39 for every dollar in foregone revenue, and a reduction in the corporate tax rate would have generated only $0.32 per dollar invested, according to this 2009-based analysis.[xix]

This analysis echoes those performed by analysts at respected, nonpartisan government institutions, including the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO).[xx] Assessing the multiplier effect of ARRA policies, the CBO identified the highest potential multiplier from purchases of goods and services by the federal government (2.5 on the high end of the range of multiplier estimates, with 0.5 at the low end), which directly stimulates demand in the economy. Transfer payments to state and local governments for infrastructure (2.2 to 0.4) had the next highest potential positive impact, while transfer payments to individuals, including SNAP benefits and unemployment compensation (2.1 to 0.4), and transfer payments to state and local governments for non-infrastructure purposes (1.8 to 0.4) followed with the next highest potential benefits. A one-year tax cut for higher-income individuals (0.6 to 0.1) and corporate tax provisions primarily designed to help business cash flow (0.4 to 0) had the smallest economic multipliers evaluated, suggesting they had the least positive impact on the economy per dollar spent.[xxi]

Additional CBO analysis focused on the employment impacts of policy options in 2011 also identified increasing aid to unemployed workers and reducing taxes for firms that increase their payroll as having the highest potential positive impacts on employment, while reducing taxes on business income and on repatriated foreign business profits showed the lowest estimated impact on increased employment.[xxii]

The CBO notes that increases in disposable income for lower-income households are more likely to boost the economy than for higher-income households due in part to more limited abilities to spend.[xxiii] The benefits of boosting disposable income for lower-income households to stimulate recovery was reinforced in a separate 2019 analysis from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Department estimated that each dollar invested in SNAP benefits would generate approximately $1.54 in economic activity when the economy is slowing.[xxiv]

With more than one in four households in New Hampshire reporting usual household expenses were at least somewhat or very difficult to cover in early January 2021, additional aid to households in need would likely get resources into the economy quickly while helping to prevent additional hardships for these and other individuals and families.

Policy Effectiveness During the COVID-19 Crisis

Although the relatively fast-moving COVID-19 crisis has provided more limited opportunities for economic analysis than the Great Recession thus far, available analyses continue to suggest both spending on public services and aid to unemployed or low-income individuals has the greatest stimulative economic effects.

The CBO conducted an analysis in September 2020 of the pandemic-related federal aid packages that had become law at that point. This analysis noted multiplier effects were much smaller during the pandemic due to distancing and other pandemic-related practices. In other words, while these policies likely had a stimulative effect, they were focused on providing relief and resources to weather the storm of the COVID-19 crisis, rather than promoting an economic recovery. Despite these smaller multipliers, the CBO estimated that the most effective economic stimulus was direct federal aid to state and local governments for COVID-19-related operations. Other spending and relief programs for governments, schools, and individuals were the next-most stimulative programs, followed by enhanced unemployment compensation and direct cash payments to individuals. Employer, business, and payroll tax changes, the Payroll Protection Program, and other aid to lending and liquidity programs to businesses were estimated to have less stimulative effects on the economy over time.[xxv]

Funding to state and local governments helps the economy because governments can then directly hire people or keep workers employed who would otherwise have been laid off, and government programs often rely on purchasing goods and services from the private sector to deliver services for residents.[xxvi] Layoffs by state and local governments generate additional unemployed workers who have resultingly lost their own incomes, and the services those workers previously provided may go undelivered. During the recovery from the Great Recession, reductions in state and local government expenditures and associated job cuts likely slowed the economic recovery significantly, and layoffs during this recovery could have a similar impact.[xxvii]

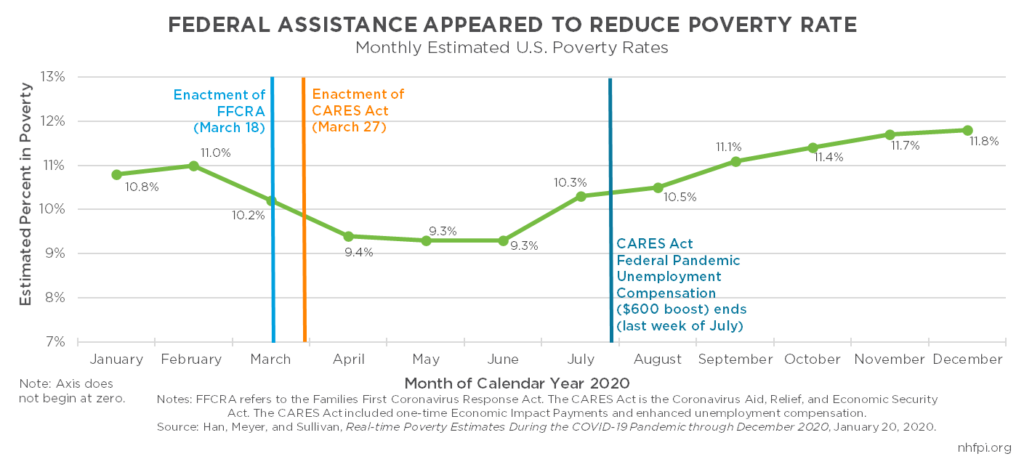

Direct payments to individuals and boosted unemployment compensation also appeared to help reduce poverty nationwide. Two separate sets of researchers examining monthly estimates of poverty during the pandemic found that, while poverty has increased to pre-pandemic levels or higher in the latter months of 2020, federal actions appeared to reduce poverty in the Spring and Summer months.[xxviii]

This research, paired with CBO analysis, suggests public policy actions designed to get resources to people in need have helped the economy during the COVID-19 crisis, as similar actions did during the Great Recession and the subsequent recovery.

Timing State Budget Support

New Hampshire policymakers have flexibility to target the timing of State Budget services to meet greater needs among Granite Staters. The next State Budget, which will fund most State-provided or -supported services from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023, will cover a key period of the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Policymakers can help ensure sufficient resources are available for services early in the budget biennium, when the needs will likely be greater, and resolve any State Budget deficit with revenue and expenditure adjustments before the end of the biennium.

At the end of State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2020, the first year of the current State Budget, the fiscal shortfall relative to planned revenues and expenditures was $81.5 million.[xxix] While revenues for SFY 2021 are not yet clear, the current State Budget will likely end with a deficit in the combined General and Education Trust Funds, unless there is additional federal aid.[xxx]

However, policymakers do not need to take action to balance the State Budget at the end of SFY 2021, which happens on June 30, 2021. The current State Budget can end in a deficit as long as that deficit is resolved in the next State Budget plan. That State Budget plan must balance revenues and expenditures, including any deficit carried forward from the prior State Budget. As a result, policymakers have until the end of SFY 2023, which is June 30, 2023, to resolve any deficit from the current State Budget or generated in SFY 2022.[xxxi]

Policymakers can work gradually toward resolving the current deficit with revenue and expenditure adjustments over the two-year budget timeline horizon. Reductions in services can be avoided early in the budget biennium, and having additional time and flexibility incorporated into the State Budget enables policymakers to respond and adjust services as the recovery unfolds, service needs are evaluated, and the State gains clarity relative to future federal actions and assistance. Revenues can also be adjusted to help fill any budget shortfall, with the two-year time horizon permitting adjustments and evaluations later in the biennium.

Maximizing Impacts of Federal Assistance and State Resources

If additional federal assistance comes to New Hampshire in a form that is unrestricted or otherwise offsets General Fund expenditures, policymakers can deploy it in ways that will effectively support the recovery. These funds could be used to provide a continuity of services and avoid reductions, bolstering the ability of the State to meet the needs of its residents.

Public health needs will likely continue to be elevated, both relative to the direct impacts of COVID-19 and to the related mental health, substance misuse, and other antecedent concerns that have been exacerbated by the crisis.[xxxii] As the pandemic continues and after it begins to subside, additional resources will be required to reduce the risk of viral spread in health care institutions and group settings as well as to meet higher overall levels of need for existing services. Resources devoted to bolstering mental health services statewide in the current State Budget will help meet these needs, but some of those budget investments will require ongoing appropriations to be effective, such as continued staffing at new and expanded facilities.[xxxiii]

People and communities with fewer resources will likely need more support following the crisis as well. For example, school districts with limited property tax bases that serve many children from low-income families may have needs that are greater than they were prior to the pandemic. The State Budget passed in 2019 provided more aid to communities with lower taxable property values per pupil and higher concentrations of students eligible for free and reduced-price school meals.[xxxiv] Property tax payers in these communities, especially those with low incomes, may be less likely to be able to afford more in local taxes to support these necessary additional costs at school districts than in other areas of the state. Students from lower-income families may also need more support from school districts to help counterbalance any disadvantages experienced disproportionately during the pandemic relative to their higher-income peers.[xxxv] If unrestricted federal aid is made available, it could be used to continue this support.

Changes to State policy enabled by new federal resources should be temporary, used as part of a direct response to the crisis, or be paired with a plan to be funded later through other revenues. Increases in targeted assistance while the overall level of need is higher, such as support for unemployed workers or food insecure households, can help in the short term and can be funded in a more limited fashion when the economy and household finances have stabilized for more Granite Staters. Permanent reductions in public revenue through tax policy changes are unlikely to be an efficient way to help the economy when compared to deploying federal funds to provide support to residents, organizations, and communities in more targeted and economically stimulative ways. Permanent changes would also increase the risk of reduced revenue after any pandemic-related assistance disappears in the future.

Conclusion

The next New Hampshire State Budget will set policy for a critical period in the recovery from the

COVID-19 crisis. While many unknowns remain and the public health crisis will likely remain acute at the beginning of the State Budget biennium, concerns specific to the pandemic may recede between the budget’s enactment and the middle of 2023. However, lower levels of risk to public health will not mean the crisis has been resolved for many individuals and families. The state’s public health infrastructure has been stretched thin, emphasizing the value of sufficient and sustained investments to help ensure access to care for all Granite Staters, including those who face lingering health effects. Additionally, severe impacts on financial security increase the risk that many people may not be able to recover quickly, and in turn slow the economic recovery overall.

The State Budget provides an opportunity to efficiently and effectively deploy resources to boost the economic recovery and meet the needs of Granite Staters. Timing is a key consideration, as both meeting these needs and boosting the economy will likely require more resources earlier in the biennium. Policymakers have time flexibility to make adjustments to revenues and expenditures to help ensure a State Budget that meets these needs is balanced by June 2023. As the recovery continues, decisions regarding adjustments made later in the biennium will benefit from more knowledge of State revenues, additional information regarding needs, and more time to determine which policies to prioritize and adjust in this particular recovery.

Federal assistance to both residents and the State may also play a critical role in the recovery. Any federal funds received that can be deployed flexibly would best support Granite Staters and the economy if they are targeted at timely, effective, and temporary investments. Keeping those dollars in the New Hampshire economy, and using them to provide resources and services to families and other residents facing the highest levels of need, has the potential to help foster an equitable, sustainable, and inclusive economic recovery.

Policymakers can design a State Budget to meet New Hampshire’s needs that will successfully help when that help is needed most during the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. As it will be enacted at a critical juncture, this State Budget will be a central piece of the foundation for that recovery in New Hampshire.

Endnotes

[i] Calculations performed using data from New Hampshire Employment Security’s GraniteStats, retrieved February 2021, based on unbenchmarked monthly Local Area Unemployment Statistics program data from the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau.

[ii] Find examples of guidance for practice changes in services to older adults, individuals with disabilities, and family-centered services on the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services website COVID-19 Guidance for Home and Community Based Care.

[iii] For more information on the New Hampshire economy and its recovery during the middle of 2020, see NHFPI’s September 2020 Issue Brief Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis and NHFPI’s January 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s Economy, Household Finances, and State Revenues.

[iv] See data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, NHFPI’s January 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s Economy, Household Finances, and State Revenues, and NHFPI’s December 2020 Issue Brief Food Insecurity and Economic Conditions in New Hampshire and the Nation.

[v] See NHFPI’s January 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s State Budget and Revenue Shortfall.

[vi] For more background information on Medicaid in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes.

[vii] Utilization in New Hampshire’s expanded Medicaid program provided evidence of Medicaid program use for mental health and substance use disorder services; see September 2017 data in NHFPI’s March 2018 Issue Brief Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire and the State Senate’s Proposed Changes. For more information on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, see NHFPI’s June 2020 post The COVID-19 Crisis Contributes to Increased Need for Mental Health Supports and the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 2020 Issue Brief The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.

[viii] For more information on the potential interactions between Medicaid reimbursement rates and workforce shortages in home- and community-based services, see NHFPI’s March 2019 Issue Brief Medicaid Home- and Community-Based Care Service Delivery Limited by Workforce Challenges.

[ix] See Mathematica’s October 2020 report for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services COVID-19 Intensifies Nursing Home Workforce Challenges; see also The New England Journal of Medicine’s October 29, 2020 Perspective The Human Touch — Addressing Health Care’s Workforce Problem Amid the Pandemic.

[x] See NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xi] See the disparate impacts by employment income levels from the early stages of the pandemic in the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy’s June 2020 Brief Employment Income Drops in More Low-Income Than High-Income Households in All States.

[xii] For more information on historical wages, see NHFPI’s September 2020 Issue Brief Challenges Facing New Hampshire’s Workers and Economy During the COVID-19 Crisis.

[xiii] For more information on the disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, see NHFPI’s April 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses and the Brookings Institution’s September 2020 report Ten Facts about COVID-19 and the U.S. Economy.

[xiv] For more on the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on student learning, see The Brookings Institution’s January 4, 2021 event post COVID-19 Sparks an Overdue Discussion on Education Reform: An Optimistic Vision.

[xv] For a full discussion and presentation of the Moody’s Analytics economic multiplier modeling, see Blinder and Zandi in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ October 2015 report The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One and Blinder and Zandi’s earlier July 2010 research How the Great Recession Was Brought to an End.

[xvi] For more information on the Food Stamp Program in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s October 2019 Fact Sheet The New Hampshire Food Stamp Program.

[xvii] For more information regarding the Moody’s Analytics economic multiplier modeling and examples of modeled policy options, see Blinder and Zandi in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ October 2015 report The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

[xviii] To see the estimated distributional impacts of the Child Tax Credit expansion under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, see the Tax Policy Center’s T09-0107 – “The American Recovery and Reinvestment Tax Act of 2009”: Reduce Child Tax Credit Refundability Threshold to $3,000, Conference Report, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Level, 2009.

[xix] For more information regarding the Moody’s Analytics economic multiplier modeling and examples of modeled policy options, see Blinder and Zandi in the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ October 2015 report The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One.

[xx] Researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture also estimated, in a July 2019 report, that a $1 billion increase in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits would increase Gross Domestic Product by $1.54 billion in the case of a slowing economy.

[xxi] For multiplier effects of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act policies estimated by the Congressional Budget Office, see the February 2015 report Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output in 2014.

[xxii] See the November 2011 testimony from the Director of the Congressional Budget Office Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in 2012 and 2013 for estimates on employment effects from selected policy options.

[xxiii] See the November 2011 testimony from the Director of the Congressional Budget Office Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in 2012 and 2013 for estimates on employment effects from selected policy options; see also the Congressional Budget Office’s September 2020 report The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output.

[xxiv] For more information on increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits and the economy, see NHFPI’s April 2020 post Food Assistance Programs Provide Critical Relief and Boost the Economy and July 2020 post Increases to SNAP Benefits Would Offset Higher Food Costs and Boost the Economy.

[xxv] To see the multipliers estimated for different pandemic-related policies, see the Congressional Budget Office’s September 2020 report The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output.

[xxvi] For more information on the economic stimulus associated with providing benefits to lower-income households relative to higher-income households, see the Congressional Budget Office’s February 2015 report Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output in 2014.

[xxvii] See The Brookings Institution’s July 2019 post A Guide to The Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measure; see also Jason Furman, Chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, October 2014 blog Advance Estimate of GDP for the Third Quarter of 2014 and The Economic Policy Institute’s May 2020 post Without Federal Aid, Many State and Local Governments Could Make the Same Budget Cuts that Hampered the Last Economic Recovery.

[xxviii] See Han, Meyer, and Sullivan’s Real-time Poverty Estimates During the COVID-19 Pandemic through December 2020 and Parolin, Curran, Matsudaira, Waldfogel, and Wimer’s October 2020 Working Paper Monthly Poverty Rates in the United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic. For more information on the federal policies enacted early in 2020 in response to the pandemic, see NHFPI’s April 2020 Issue Brief The COVID-19 Crisis in New Hampshire: Initial Economic Impacts and Policy Responses.

[xxix] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s LBA Snapshot Analysis of FY 2020 Surplus/(Deficit) from January 9, 2021.

[xxx] See NHFPI’s January 2021 presentation New Hampshire’s State Budget and Revenue Shortfall.

[xxxi] Based on NHFPI analysis of RSA 9, the New Hampshire statute that governs the State Budget process, and confirmation with the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant. In extreme scenarios, the State may encounter cash flow issues, but the State Treasury Department reported sufficient cash in January 2021, and the Rainy Day Fund may cover budget shortfalls from the current biennium sufficiently.

[xxxii] For more information on the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, see NHFPI’s June 2020 post The COVID-19 Crisis Contributes to Increased Need for Mental Health Supports and the Kaiser Family Foundation’s August 2020 Issue Brief The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.

[xxxiii] See NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxxiv] See NHFPI’s December 2019 Issue Brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021.

[xxxv] For more on the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandmic on student learning, see The Brookings Institution’s January 4, 2021 event post COVID-19 Sparks an Overdue Discussion on Education Reform: An Optimistic Vision and The Economic Policy Institute’s September 2020 report COVID-19 and Student Performance, Equity, and U.S. Education Policy.