Crafting a state budget is a long process that, in New Hampshire, begins well before the legislators who vote to make the budget law are elected. State statute requires the new governor, elected in November, to submit a complete budget proposal for the next biennium by February 15 of each odd-numbered year. Given that New Hampshire’s budget represents spending decisions for more than $5 billion of public money annually, a process for thoughtfully determining needs, priorities, and tradeoffs must begin earlier than November to be effective and thorough.

The state budget process is broken up into three phases: the Agency Phase in August and September, the Governor’s Phase from October 1 to February 15, and the Legislative Phase from February 15 until June 30, when the prior biennium’s budget expires and a new state fiscal year begins. The governor and governor-elect are now, from November 18 to November 22, holding agency budget hearings, during which each agency is scheduled to present their proposed budgets.

In 2014, the Legislature made substantial changes to the Agency and Governor’s Phases of the budget process. Prior to these changes, state agencies would prepare “maintenance” and “change” requests, where maintenance requests represented the costs of providing the same level of service funded in the prior fiscal year, accounting for population and economic changes and other criteria set forward by the governor. Maintenance and change requests, however, could grow well beyond the scope of the prior budget, especially if agency obligations were underfunded in the prior biennium and fully funded in the maintenance budget.

The new process requires agencies to submit “efficiency budgets” and “additional prioritized needs.” Efficiency budget expenditures are constrained by projections for state revenue generated by the governor’s office. For this first cycle of the new process, the projections were produced by the Governor’s Consensus Revenue Estimating Panel in July 2016; however, this panel was established by the outgoing governor’s Executive Order and may not meet again under subsequent administrations. Based on these projected revenue constraints, the governor provided state agencies with spending targets, with any expenditures requested beyond those targets to be in the additional prioritized needs request.

This process involves the governor’s office directly in the budget process much earlier, as the governor has authority to set spending targets for individual agencies based on his or her own priorities. Agencies seeking higher targets have already interacted with the governor’s office to make their cases for a greater portion of the projected revenue, and the governor has to decide where to set these spending targets prior to agency budget finalization. The agencies are also required to make program prioritizations to craft budgets within the revenue constraints; prior to these process changes, there may have never been public documentation of these agency decisions. These efficiency budgets also require agencies to publish performance measures, and give agencies the opportunity to provide input on the value and success of programs under their authority.

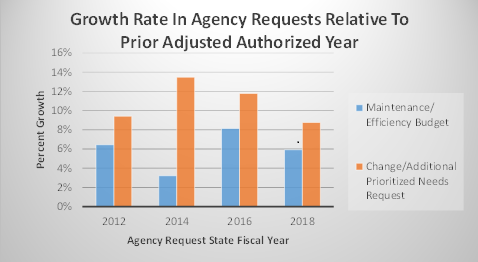

How is this new process changing the agency budget requests? This graphic shows the percentage difference between the aggregate agency budget maintenance or efficiency requests and the adjusted authorized expenditures budgeted for the prior year.

We only have one year of data, but we can see that the new process did not dramatically change the amounts agencies have requested relative to variation from other factors in prior years. The efficiency budget grew at almost exactly the average rate the three prior maintenance budgets grew (5.9 percent), and the additional prioritized needs budget growth was lower than the average change request growth from the previous three cycles (11.6 percent in the old process and 8.8 percent in the new). The change to a budget process that constrains agencies based on projected revenues may change budget growth in future years, especially if revenues are expected to be more limited or declining, but this first year of implementation did not appear to yield significant aggregate changes in agency-proposed state spending growth.