The COVID-19 crisis is producing disproportionate impacts on New Hampshire’s racially and ethnically diverse residents, with new data mirroring trends also evident at the national level. Individuals identifying as a non-white race or as ethnically Hispanic or Latino appear to be more likely to suffer medically from COVID-19, the disease caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. Economic factors such as poverty and lower incomes, and the related implications for housing options, access to health care services, and available alternatives for avoiding the virus related to distancing, work, and providing care are likely contributing to these disparities. These uneven impacts and the intersections between contributing factors help show the extent to which those already at a disadvantage are likely to be hurt more deeply by this crisis.

On the week of April 13, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) began releasing weekly demographic data for identified cases of COVID-19. The report for the week of April 27 indicated that, while race or ethnicity data were not available for all individuals, this information is known for 79 percent of infections, 86 percent of hospitalizations, and 67 percent of deaths in New Hampshire. Both the U.S. Census Bureau and the DHHS identify race and ethnicity separately, so someone of any racial group, such as white or Asian, could also be Hispanic or Latino, which is an ethnic group, or identify as not Hispanic or Latino.

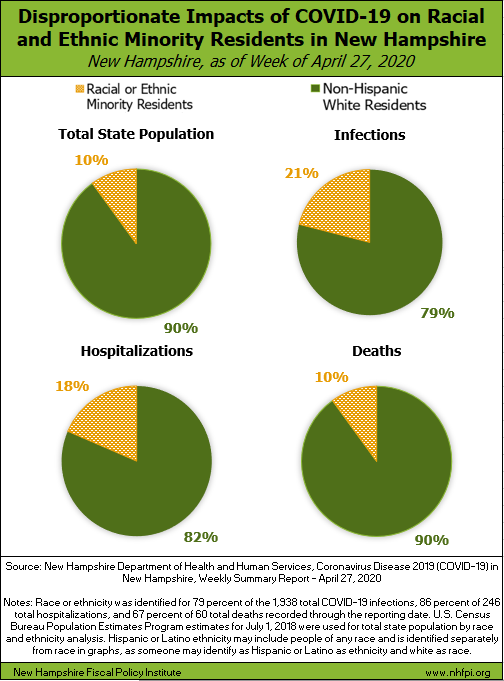

While people identifying as non-Hispanic white comprised 90.0 percent of New Hampshire’s population, based on 2018 estimates, they comprised only 79.0 percent of infections and 81.5 percent of hospitalizations.

The DHHS identifies about 6.8 percent of infections, 8.1 percent of hospitalizations, and 7.5 percent of deaths as among those identifying as Hispanic or Latino, which includes any race as long as the individual identifies as Hispanic or Latino in the DHHS data, while Hispanic or Latino individuals comprise about 3.9 percent of the state’s population. People who are Black or African American and not Hispanic or Latino were an estimated 1.4 percent of New Hampshire’s population, while they comprised 5.6 percent of infections and 3.8 percent of hospitalizations, although there were no deaths. Asians also had no recorded deaths in New Hampshire, but were 3.2 percent of infections and 4.7 percent of hospitalizations, while being an estimated 3.0 percent of the population.

While the percentage of deaths that were people who identified as white matched the proportion of the population that is white as a whole in New Hampshire, the overall higher rates of infection and hospitalization for Hispanic or non-white individuals suggests nationally-recognized trends of greater risk for racial or ethnic minority groups are present in New Hampshire as well.

Factors Contributing to Disparities

Distancing is more difficult to accomplish successfully in areas with higher population density. Individuals or family members who have less space between themselves, their neighbors, or anyone else living in a shared room, building, or area, will likely be at higher risk of catching the 2019 novel coronavirus from another person. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified population density associated with institutionalized racism in residential housing segregation as a possible factor creating adverse living conditions for racial and ethnic minority individuals seeking to avoid contracting the virus.

Poverty and limited access to resources may lead to reduced options for residents to protect themselves from contracting the virus. These factors could prevent individuals from staying well or getting well as easily as those with more resources. The CDC indicates many members of racial or ethnic minority groups live in neighborhoods that are further from grocery stores or medical facilities. The CDC also noted Hispanic and Black or African American workers are more likely to be employed in the service industry than their white counterparts, potentially indicating more may work at jobs that may be deemed essential and may place them at greater risk of encountering the virus at work. Analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation also indicates Black or African American and Hispanic individuals were less likely to have a usual source of health care other than the emergency room than white individuals in 2018.

Relative to both population density and income levels, individuals in New Hampshire identifying as something other than non-Hispanic white are at statistical disadvantages to their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

Population Density

New Hampshire’s two largest cities, Manchester and Nashua, together account for approximately 15 percent of New Hampshire’s total population, based on the most recent available five-year averaged data from the U.S. Census Bureau. However, these two cities are collectively home to half of the population self-identifying as Black or African American, and about half the population identifying their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino. About one in three New Hampshire residents identifying their race as Asian live in Manchester or Nashua, as well as one-quarter of those identifying as being of two or more races.

As Manchester and Nashua have much higher populations than any other municipalities in New Hampshire, the public health risks associated with population density are likely higher in those two cities than in most other parts of the state. Relative to the state, higher proportions of the population in these two cities are people identifying as something other than white and non-Hispanic.

Access to Resources

Poverty rates for racial and ethnic groups vary across the state as well. In 2018, an individual less than 65 years old and earning less than $13,064 was considered to be in poverty based on the federal poverty threshold; poverty-level income for a family of three, with one child, was less than $20,212.

The average poverty rate for those identifying as non-Hispanic white was 7.2 percent, or about one in fourteen people in the state, based on the most recent five-year data. In contrast, about one in every five of those identifying as Black or African American and about one in six identifying as Hispanic or Latino were in poverty. In addition, approximately one in every ten Granite Staters identifying as Asian and one in eight identifying as two or more races lived in poverty.

Poverty, Population Density, and Racial or Ethnic Minority Groups in New Hampshire’s Census Tracts

The U.S. Census Bureau employs Census Tracts to help identify population characteristics at the neighborhood level. While small-area estimates are less reliable than those for areas with higher populations, examinations of localized data provide insights into the intersection between poverty, population density, and race.

Of the 35 Census Tracts with the highest estimated poverty rates in New Hampshire between 2014 and 2018, 18 (51 percent) are also included in the 35 New Hampshire Census Tracts estimated to have the highest percentage of residents identifying as something other than non-Hispanic white. Of these 18 Census Tracts, 13 (72 percent) are in Manchester, and 16 (89 percent) are either in Manchester or Nashua. These data suggest some of the most impoverished places in New Hampshire are also those with the highest concentrations of people identifying as something other than white and non-Hispanic, and are in the state’s two largest cities, where higher population densities may make social distancing to avoid contact with the 2019 novel coronavirus more difficult.

Reducing Disparities

Inequalities in incomes, and the geographic locations of available housing options, affect the abilities of people who were already at a disadvantage to avoid contracting COVID-19 and to access treatment when it is identified. The economic disparities between New Hampshire’s white population and non-white population likely are key factors, among others, contributing to the difference in infection and hospitalization rates in New Hampshire. Increased access to health care, more housing opportunities, and enhanced economic or family care supports would widen the options available for people with fewer resources to stay safe and healthy during this pandemic.

Building an economic recovery that seeks to lift up all Granite Staters, reduce the uneven impacts of economic hardship, and ensure those previously disadvantaged unjustly are equitably included in such a recovery, will help make all individuals and families in New Hampshire more resilient while recovering from this crisis and in the future.

– Phil Sletten, Senior Policy Analyst