This second edition of New Hampshire Policy Points provides an overview of the Granite State and the people who call New Hampshire home. It focuses in on some of the issues that are most important to supporting thriving lives and livelihoods for New Hampshire’s residents. Moreover, the book addresses areas of key policy investments that will help ensure greater well-being for all Granite Staters and a more equitable, inclusive, and prosperous New Hampshire.

New Hampshire Policy Points is intended to provide an informative and accessible resource to policymakers and the general public alike, highlighting areas of key concerns. Touching on some important points but by no means comprehensive, each section within New Hampshire Policy Points includes the most up-to-date information available on each topic area. The facts and figures included within this book provide useful information and references for anyone interested in learning about New Hampshire and contributing to making the Granite State a better place for everyone to call home.

To purchase a print copy or download a free digital PDF of New Hampshire Policy Points, visit nhfpi.org/nhpp

New Hampshire’s transportation infrastructure includes the roads, bridges, railroads, bus routes, pedestrian and bicycling trails, airports, ports, and waterways used to move people and goods to destinations that support national and international commerce. These transportation systems are essential for residents, visitors, and goods moving in, out, and across the state.

Roads and Bridges

With Granite Staters heavily reliant on motor vehicles to travel, well-maintained roads and bridges are of critical importance. The maintenance of roads is a shared responsibility between State and local governments in New Hampshire, with significant federal funding supporting key road projects. According to information published in 2024, the New Hampshire Department of Transportation (NHDOT) managed 4,598 (27.5 percent) of the 16,725 miles of public roads in the state, with the remainder managed by local governments.[1] Of NHDOT’s road miles, about 75 percent were reported eligible for federal funding to support improvements and repairs in 2023, while the remaining 25 percent were only eligible for State funding.[2] In addition, the State managed 2,159 State-owned bridges.[3]

The State reported well-maintained major roads in July 2024, with nearly 100 percent of divided highways and 94 percent of statewide corridors in good or fair condition. However, only 88 percent of regional corridors, and 63 percent of local connectors, were in good or fair condition, with the rest in poor or very poor condition.[4]

Local governments were responsible for about 12,127 miles of roadway in New Hampshire in 2024.[5] An additional 1,690 bridges were under the jurisdiction of New Hampshire’s municipalities.[6] Rural communities with lower population densities often have more miles of road per resident to maintain. They may depend on more State funding for maintenance compared to localities with a larger property tax base. Rural communities with lower incomes and smaller tax bases may also find it particularly challenging to afford the high costs for road and bridge repairs with locally generated funds.

As state and local governments budget for planned repairs or replacement of roads and bridges, policymakers may have to amend plans for an increased deterioration rate as construction methods and materials have a shorter life span because of a changing climate. Engineers have noted that increased temperatures and more frequent extreme heat events can significantly affect transportation infrastructure.[7]

Planes, Trains, and Trails

New Hampshire had 133 registered airports in 2021. As of 2024, 25 airports were open to the public, including three served by commercial passenger airlines.[8] Manchester-Boston Regional Airport is the largest commercial airport located in the Granite State.

As of August 2024, the NHDOT reported approximately 443 miles of operating rail lines, of which over 200 miles were maintained by the State government. Two privately-owned Amtrak rail lines serve New Hampshire, including the Downeaster, which stops in Dover, Durham, and Exeter on its path from Maine to Massachusetts, and the Vermonter, which runs along the Connecticut River and stops in Claremont. Tourists are also carried short distances on the Conway Scenic Railroad, the Mount Washington Cog Railway, and the rail lines operated by Granite State Scenic Railways, while other active rail lines in New Hampshire are dedicated to freight.[9]

As of 2022, New Hampshire was also home to 27 state-owned rail trails that totaled 338 miles. The longest trail, the Northern Rail Trail, is approximately 58 miles and stretches from Boscawen to Lebanon, while the shortest trail, Profile Rail Trail, is a 1.5-miles trail in Bethlehem. Rail trails may have considerable economic impact through the recreation, tourism, and commuting opportunities they offer. A 2022 economic impact analysis of nine New Hampshire rail trails revealed the trails generated over $2.7 million dollars in tax revenue and supported over 160 jobs.[10]

Public Transportation

New Hampshire has limited public transit options for residents across the state. Many communities have made efforts to establish local public transit, often benefiting from federal and private grants. Based on NHDOT-reported information in 2024, there are 12 local bus systems in the Granite State, primarily based in cities in the state but also serving more rural areas, such as Carroll County and towns in the White Mountains. Several intercity bus routes also provide access to interstate travel, primarily to metropolitan Boston.[11] In State Fiscal Year 2024, the NHDOT reported approximately 2.5 million combined public transit rides across the state, an 18.2 percent increase from 2023. Though this is only about 76 percent of ridership compared to 2019 pre-pandemic rates, there has been a consistent increase in the number of rides taken on public transit since 2022.[12]

Despite these efforts, only 34 of New Hampshire’s communities have a regular fixed bus route, according to the New Hampshire Transit Association. Additionally, the Association, in collaboration with Transport New Hampshire, determined that 2019 funding levels for public transportation in New Hampshire, including state and federal funding, ranked 49th in the nation. While some communities that lack fixed routes have volunteer or non-profit efforts to support transportation services, particularly for older adults, an overall lack of public transportation infrastructure limits Granite Staters’ access to reliable transportation.[13]

New Hampshire’s lack of public transit may disproportionately impact certain populations. Data collected in New Hampshire between 2018 and 2022 show people with lower incomes made greater use of public transit; while about 32 percent of people who drove to work alone made less than $35,000 per year, about half of public transit commuters (46.8 percent) had similarly low incomes. About 5.3 percent of people who drove to work alone were within 150 percent of the poverty threshold, compared to 15.4 percent of public transit riders.[14] Furthermore, about 1.5 percent of New Hampshire households had no vehicles available.[15]

Getting to Work

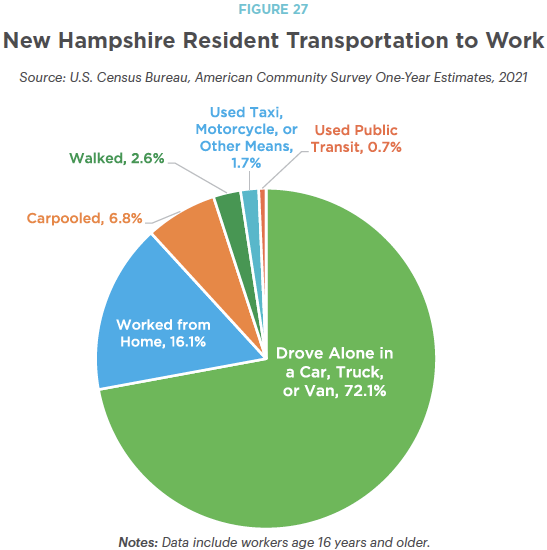

Most New Hampshire residents primarily relied on cars, trucks, and vans to get to work during 2023. Approximately 79 percent of workers age 16 and over traveled by motor vehicle to their jobs; about 7 percent of all workers carpooled, while just over 72 percent drove alone. About 3 percent walked and approximately 2 percent took a taxicab, motorcycle, or some other means. Only an estimated 0.7 percent of commuters took public transit to work. Although this number may be low, marginalized communities and those with low incomes are more likely to rely on public transit to get to work. These communities include people who speak languages other than English at home, who identify as Hispanic or Latino, who were born outside of the U.S., and who work in service occupations. The current public transit infrastructure in New Hampshire is not a time-efficient means to get to work; while the average commute time for people driving alone or carpooling was slightly more than 27 minutes, the average commute time by public transit was about 62 minutes, requiring more time out of the day even for those who have access to public transit.[16]

About 16 percent of working Granite Staters connected remotely from home in 2023, an increase from about seven percent in 2019, but a decrease from approximately 19 percent in 2021.[17]

Federal Investments and Ongoing Maintenance

The federal government has enhanced funding for transportation systems through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which boosted funding for existing federal grants and provided funding for new transportation initiatives. The NHDOT projects federal funding over a five-year period from 2022 to 2026 for New Hampshire’s highway programs will increase by about $244.1 million (24.5 percent) compared to the prior five years, and public transportation funding will increase by an estimated $33.6 million (34.4 percent). New funding dedicated to bridges ($225.0 million), airports ($45.6 million), and electric vehicle charging stations ($17.3 million) is also expected to flow to the State from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act during this time frame.[18] The DOT projects that, with these added investments, the number of structurally deficient State bridges would drop from 119 in 2023 to 90 in 2026, but will return to 118 in 2034 as more bridges age and become structurally-deficient.[19] The DOT still expects to pave fewer miles of roads in the coming decades, even with the funding increase, and road conditions are expected to decline.[20]

While federal funding for transportation in New Hampshire is increasing, the Granite State has some of the lowest per capita transportation funding in the country, ranking 44th among US states at just $0.33 per resident in 2021.[21] The median per capita spending for all US states during that year was $5.70. Continuous maintenance and repair can help lengthen the lifespan of transportation infrastructure. Keeping roads and bridges in good condition, rather than delaying repairs until they deteriorate, is generally more cost effective; in 2016, the NHDOT reported that preserving bridges can have a benefit-cost ratio as high as ten to one.[22]

Additional upgrades and maintenance will likely be needed. The American Society of Civil Engineers, in their most recent state-specific assessment from 2017, gave New Hampshire’s roads, bridges, and rail lines each a grade of C-, while aviation earned a C+, and ports received a D+ as a grade.[23]

Reliable transportation and the infrastructure that supports it are critical to people’s lives and livelihoods. Ongoing public investments in the roadways and bridges that people rely upon, as well as public transit options and the efficient movement of goods throughout the state, can both enhance access to transportation and employment options and help reduce long-term costs for the State, local governments, and all Granite Staters.

• • •

This publication and its conclusions are based on independent research and analysis conducted by NHFPI. Please email us at info@nhfpi.org with any inquiries or when using or citing New Hampshire Policy Points in any forthcoming publications.

© New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, 2024.

Endnotes

[1] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s 2024 Roads and Highways Facts & Figures.

[2] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s 2023 Fact Book.

[3] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s 2023 Fact Book.

[4] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s July 2024 Pavement Condition document.

[5] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s 2024 Roads and Highways Facts & Figures.

[6] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s NHDOT Facts webpage.

[7] See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s, Climate Change Impacts on Transportation, and U.S. Department of Transportation’s, Climate Action.

[8] See New Hampshire’s State Airport System Plan: System of Public-Use Airports in New Hampshireand New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s NHDOT Facts.

[9] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s Rail Transportation webpage.

[10] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s New Hampshire Rail Trails Plan.

[11] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s Local Transit Services webpage.

[12] Email communication with NHDOT.

[13] See the New Hampshire Transit Association’s 2022 report Public Transportation in New Hampshire.

[14] See U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Means of Transportation to Work by Selected Characteristics, S0802.

[15] See U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Means of Transportation to Work by Selected Characteristics, S0802.

[16] See U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Means of Transportation to Work by Selected Characteristics, S0802.

[17] See U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, Selected Economic Characteristics, DP03.

[18] See New Hampshire Department of Transportation’s 2023-2032 Draft Ten Year Plan presentation prepared for the Senate Transportation Committee.

[19] See New Hampshire’s House Public Works and Highways Committee HB 2024 2025-2034 Draft Ten Year Plan Work Session, slide 11.

[20] See New Hampshire’s House Public Works and Highways Committee HB 2024 2025-2034 Draft Ten Year Plan Work Session, slide 9.

[21] See AASHTO 2023 Survey of State Funding for Public Transportation.

[22] See State of New Hampshire’s September 2016 Performance Audit Report for the Department of Transportation Bridge Maintenance.

[23] See American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2017 Report Card for New Hampshire’s Infrastructure.