This second edition of New Hampshire Policy Points provides an overview of the Granite State and the people who call New Hampshire home. It focuses in on some of the issues that are most important to supporting thriving lives and livelihoods for New Hampshire’s residents. Moreover, the book addresses areas of key policy investments that will help ensure greater well-being for all Granite Staters and a more equitable, inclusive, and prosperous New Hampshire.

New Hampshire Policy Points is intended to provide an informative and accessible resource to policymakers and the general public alike, highlighting areas of key concerns. Touching on some important points but by no means comprehensive, each section within New Hampshire Policy Points includes the most up-to-date information available on each topic area. The facts and figures included within this book provide useful information and references for anyone interested in learning about New Hampshire and contributing to making the Granite State a better place for everyone to call home.

To purchase a print copy or download a free digital PDF of New Hampshire Policy Points, visit nhfpi.org/nhpp

Public services are funded at multiple levels of government in New Hampshire. These levels of government, including the federal, state, county, city or town, school district, village, or other local governing body, typically have legal and fiscal relationships with one another. These levels of government also collect and expend revenue, typically through budget processes.[1] The New Hampshire State Budget is the largest of these appropriation processes within the State, and impacts the services provided statewide as well as the considerations of local government policymakers.

State, County, and Local Governments

Some services, such as the U.S. Small Business Administration or Medicare, are funded directly by the federal government.[2] Others are funded mostly or entirely by the State.[3] Other key services are funded by local governments, such as local police and fire departments, although grants or assistance programs from the State or the federal government may help cover expenditures.[4]

Cities and towns provide and support key services for their residents, including but not limited to public safety, waste management, and infrastructure.[5] Local school districts, which can be integrated within municipalities or be governed separately, provide public education.[6] Local governments may also cooperate with one another across borders, and may have other jurisdictions or governing bodies within their borders, such as village districts.[7]

County governments oversee the register of deeds, county attorneys, county sheriffs, correctional facilities, and county nursing facilities. Counties are also responsible for funding most of the non-federal portion of Medicaid for longterm services and supports provided to eligible older adults and adults with physical disabilities who are county residents. County revenues rely on property taxes, Medicaid and limited Medicare payments, fees, and other locally-generated revenues to fund services.[8]

The State government provides the widest variety of services in New Hampshire. Responsibilities of the State government include public health, human services, education, public utilities, economic development, environmental protection, public safety, transportation, and other key areas of public service provision. Like the federal government, the State government is divided into the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The Governor and Legislature are responsible for crafting and adopting a State Budget every two years, which is the primary method of directing public investments to support residents, businesses, and the economy.[9]

The Process for Building the State Budget

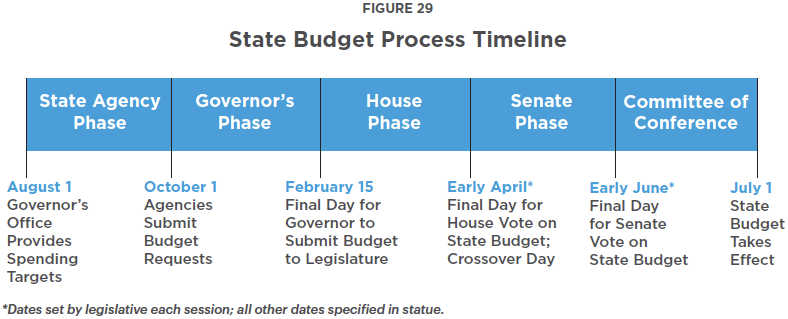

The New Hampshire State Budget, which funds most State services for a two-year period, is constructed in five phases over the course of a year leading up to enactment.

Agency Phase: In the summer of each even-numbered year, State agencies craft their agency budget requests. The agencies will estimate the funding levels needed to continue operating at existing capacity, and identify funding changes to either enhance their services or better fulfill their legal requirements or objectives. By August 1 of each year, the Governor is required to produce revenue estimates and provide expenditure targets for each State agency. The State agencies must subsequently build their ”efficiency budget” up to those targets, prioritizing their most important operations for funding. Funding proposed above the “efficiency budget” levels are identified as “additional prioritized needs.” State agencies must submit their budget requests to the Department of Administrative Services by October 1.[10]

Governor’s Phase: Law requires the Governor to hold public hearings on the agency budget requests by December. The Governor is also required to invite the Governor-elect, the Chairs of the House Finance Committee and the Senate Finance Committee, and the Commissioner of Administrative Services. The Governor, or Governor-elect who takes office the following January, is required to submit a State Budget proposal to the Legislature by February 15. The Governor’s budget proposal is typically introduced into the Legislature as two separate bills, House Bill 1 and House Bill 2, and is accompanied with a budget address. The Governor’s budget proposal must also include revenue projections for the next two years.[11]

House Phase: Once the Governor’s proposal has been submitted to the Legislature, the House of Representatives first considers the State Budget proposal. Both House Bill 1 and House Bill 2 are referred to the House Finance Committee. The Committee then splits into three subcommittees, typically called Divisions, to consider, revise, reconstruct, and vote separately on different portions of the State Budget.[12] The Divisions spend weeks making their proposed changes and report back to each other when the full House Finance Committee reconvenes. In the interim, the House Ways and Means Committee will produce revenue estimates for the General, Education Trust, Highway, and Fish and Game Funds for the House to consider and, if it chooses, adopt as its revenue estimates for the budget process. The full House Finance Committee reconvenes to vote on the Division-level changes and any other changes made as a full Committee before voting to recommend the proposed State Budget to the entire House of Representatives. The entire House then considers the State Budget, including amendments to the Governor’s proposal from the Committee and any other amendments brought forward by members. If the State Budget passes the House, consideration of the two State Budget bills moves to the Senate. The House vote on the State Budget is typically held in early April.[13]

Senate Phase: After the House phase, the Senate takes up the State Budget proposal and sends it to the Senate Finance Committee for consideration. The Senate Finance Committee has significantly fewer members than the House Finance Committee, and as a result does not separate the work into Divisions.[14] The Senate Ways and Means Committee produces revenue estimates, typically after April tax returns are measured and can be considered in its projections, which typically leads to higher revenue projections than the House’s estimates.[15] The Senate Finance Committee makes its changes to the State Budget before approving a recommendation to the entire Senate, and then the Senate as a whole amends and votes on the bills that become the Senate version of the State Budget, typically near the beginning of June.[16]

Committee of Conference: If the House does not agree with the Senate’s changes to the two State Budget bills, then the two chambers will form a Committee of Conference to resolve the differences between the House’s versions and the Senate’s versions. That Committee will often produce its own set of revenue estimates and make modifications to the State Budget bills based on the differences between the versions from each legislative chamber, as well as other changes made to reach agreement between the two chambers. Once the Committee of Conference agrees on a single version for each of the State Budget bills, they are considered by the full House and the full Senate, without opportunities for further amendments from members of either chamber. If both chambers vote for the State Budget bills with majorities in each chamber, then the bills are sent to the Governor for a signature, veto, or approval without signature.[17]

Inside the State Budget

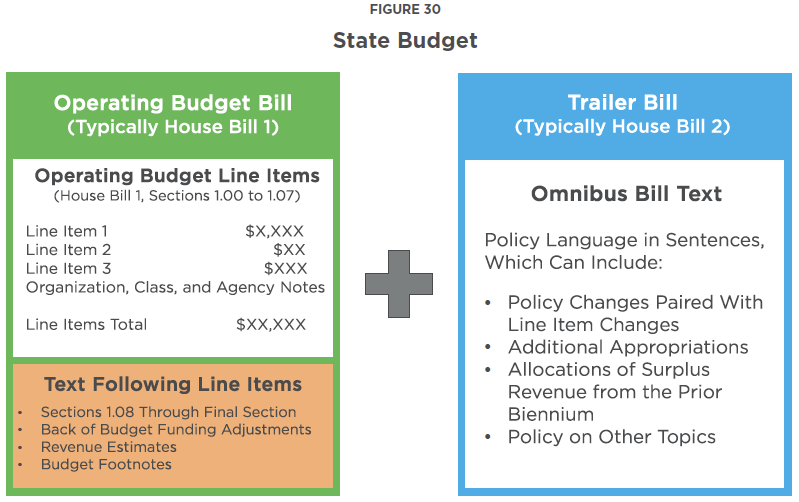

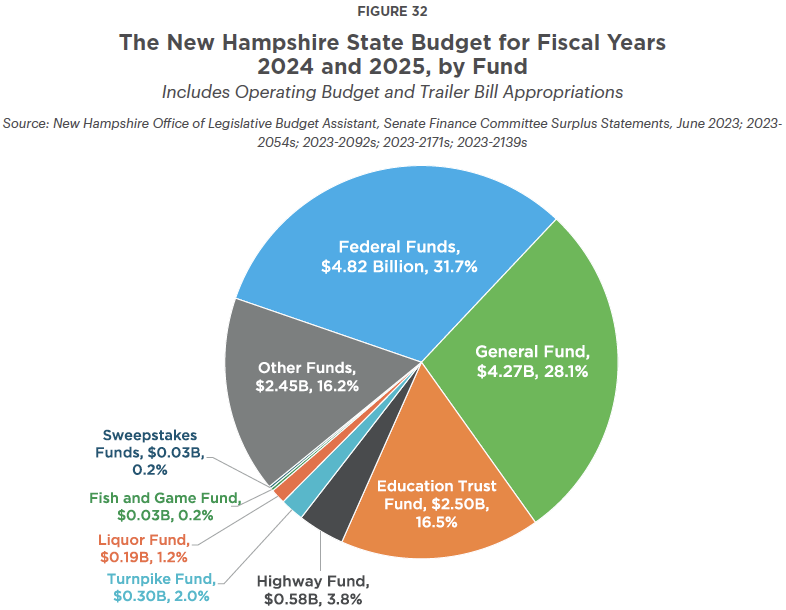

The New Hampshire State Budget consists of two documents that are enacted as separate pieces of legislation. Together, these documents appropriate funding for most, but not all, State programs, operations, and services over a period of two fiscal years.[18] The State Budget for State Fiscal Years (SFYs) 2024 and 2025, which includes July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2025, appropriated $15.17 billion in total funds.[19]

The Operating Budget Bill, typically House Bill 1, appropriates most of the money allocated through the State Budget. This bill includes line-item appropriations associated with each agency, as well as a limited amount of text directing or modifying funds outside of the line items.

The Trailer Bill, typically House Bill 2, is an omnibus text bill that can support changes and set up legal frameworks for appropriations made in the Operating Budget Bill. However, it can also include appropriations made independently in House Bill 2, as well as changes to State law that do not impact appropriations. During some legislative sessions, bills on a wide variety of topics that are considered separately from the State Budget are attached to the State Budget through incorporating them into the Trailer Bill.[20]

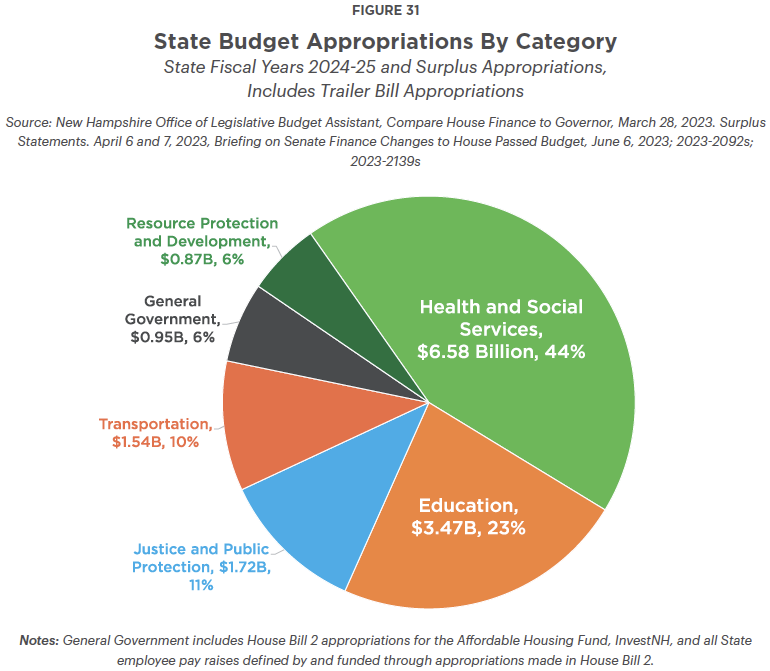

All funding in the State Budget can be divided into six categories of expenditures, which are broad service areas to which the State devotes resources. Health and Social Services, which constitutes nearly all of the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services budget, has received the largest amount of appropriations through the State Budget process in both the current State Budget and in historic appropriations since at least 2005. This category includes Medicaid, which provides health coverage to more than 180,000 New Hampshire residents and is funded through a combination of State and federal revenues.[21]

Education, the second-largest category, includes funding for the University System, the Community College System, the Lottery Commission, the Police Standards and Training Council, and the Department of Education. About 60 percent of the appropriations in the Education category are funds for local public education distributed by the Department of Education through the State’s education funding formula.[22]

Together, the two categories of Education and Health and Social Services accounted for two out of every three dollars appropriated by the Legislature in the State Budget for SFYs 2024 and 2025. However, the remaining four categories still accounted for a significant portion of State operations and key public services.

The Administration of Justice and Public Protection includes a wide variety of law enforcement and regulatory agencies, ranging from the entire judicial branch of State government to the Departments of Safety, Energy, Insurance, Labor, Banking, Corrections, Justice, Employment Security, Military Affairs and Veterans Services, and Agriculture, Markets, and Food, as well as other agencies. Justice and Public Protection received about 11 percent of all appropriations made by the Legislature in the SFYs 2024-2025 State Budget.[23]

The Transportation category, which reflects the Department of Transportation budget, accounted for ten percent of appropriations. General Government, which includes the operations of the legislative branch as well as the Departments of Revenue Administration, Treasury, Administrative Services, Information Technology, and other agencies, totaled about six percent of appropriations, with less than a billion in total funds. Resource Protection and Development includes the Pease Development Authority and the Departments of Environmental Services, Fish and Game, Business and Economic Affairs, and Natural and Cultural Resources; total funding for this category was slightly lower than funding for General Government.[24]

Policymakers have also organized the State Budget into funds. These funds serve different purposes and behave similarly to accounts; money flows in from various sources and out to support services. Funds are typically, but not always, for dedicated purposes.[25]

Nearly one in three dollars supporting State Budget-funded operations come from the federal government, including funding for key programs such as transportation, clean drinking water infrastructure and management, and aid to individuals and families through Medicaid and food assistance programs. The federal funding for these programs that flows through the State Budget appear as federal funds in the State’s accounting, and while there is a wide diversity of funding streams through federal programs and grants, federal funds are the largest single set of funds in the State Budget.

The State Budget’s General Fund is the State’s primary operating fund. Most debates surrounding funding priorities for the State Budget focus on General Fund money, as legislators have the fewest barriers to allocating these dollars to finance their priorities. Most funding for the General Fund is from State taxation, with non-tax revenue support from Liquor Commission profits and certain other non-tax revenue sources.[26]

The Education Trust Fund is dedicated to supporting the grants to local public school districts, which are calculated using the State’s education funding formula. In recent years, the purposes of the Education Trust Fund have been expanded to include State school building matching funds for local governments, special education aid, public charter school funding, and the Education Freedom Accounts that provide grants to eligible households with children who are not in public school. The Education Trust Fund carries any unspent surplus dollars forward from year to year, but in the case of a shortfall, the General Fund contributes to the Education Trust Fund to ensure obligations are met. The two funds also share many key revenue sources and are often analyzed together.[27]

Other key State funds include the Highway Fund, which collects motor fuel tax and vehicle fees for the construction and maintenance of public roads; the Turnpike Fund, which holds revenue collected from tolling turnpikes and deploys those dollars for the upkeep and maintenance of the 89 miles of highways owned by the State Bureau of Turnpikes; the Liquor Fund, which temporarily holds funds associated with operating the Liquor Commission before they are transferred elsewhere or spent; the Fish and Game Fund, where funds from hunting and fishing licenses are collected to help run the Fish and Game Department; and the Sweepstakes Fund, which holds dollars used in the administration of the Lottery Commission.[28]

Aid to Local Governments

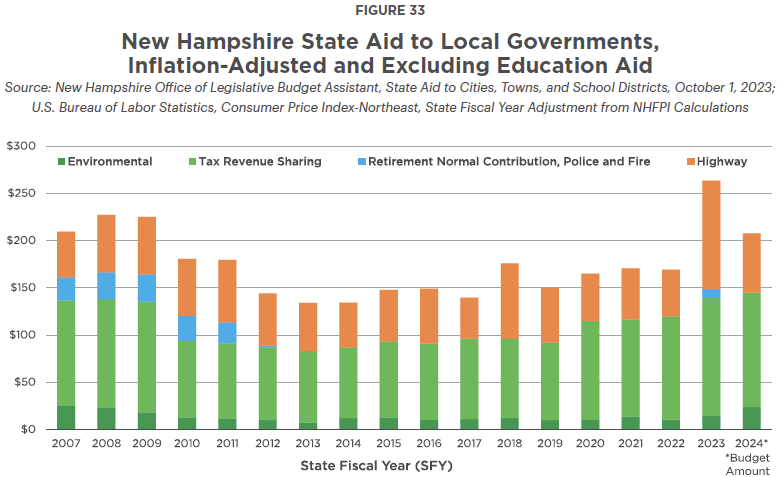

While the State receives significant funding from the federal government, State funding is a substantial component of local government budgets in New Hampshire. The State contributes some dollars to paying the non-federal share of county Medicaid long-term services and supports costs for older adults and adults with physical disabilities.[29] The State contributes substantially more money to municipal governments for a wide array of services, including general revenue sharing, funds for road and bridge maintenance, and environmental infrastructure projects such as wastewater treatment plants.[30]

State aid to municipal governments has varied considerably over time, both in volume and composition. Adjusting for inflation suggests that aid to municipalities dropped substantially following the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, and did not return to pre-Great Recession levels of spending power until SFYs 2023 and 2024. One-time highway-related State appropriations boosted funding in SFYs 2018 and 2023 substantially, and the most recent three State Budgets have included substantial increases in general revenue sharing. While increasing in aggregate in the two most recent State Budgets, more of total revenue sharing appropriations have been shifted to being based on population and funded through revenue raised by the Meals and Rentals Tax. Previous revenue sharing strategies included more targeting of aid toward communities with higher levels of need.[31] The State previously paid for 35 percent of local public police, fire, and teacher employee retirement costs; since SFY 2012, the State has contributed to these retirement costs solely through a smaller, onetime contribution in SFY 2023.[32]

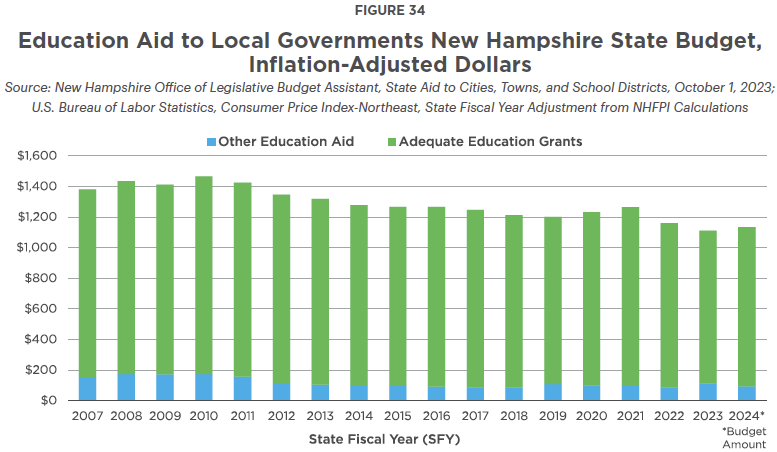

The majority of State funding that flows to local governments is delivered through education-related aid to school districts. The State’s education funding formula, which determines the amount of Adequate Education Aid a community or school district receives, directed more than $1.0 billion of State Budget spending in SFY 2024.

Adjusting for inflation, education aid for local public schools has declined since 2010. This decline is in part due to policy decisions, but is primarily driven by lower enrollment in New Hampshire public schools. Statewide student enrollment peaked in the 2002-2003 school year, and the education funding formula’s appropriations are driven by student enrollment.[33] Decisions in the current State Budget boosted the average amount per pupil in State aid delivered, although State supports are still well below average per pupil costs reported by school districts.[34] While New Hampshire had the 10th highest estimated total revenue per pupil from all sources among the 50 states in fiscal year 2022, it had the smallest percentage of local public education revenue coming from the State government, resulting in greater reliance on local property taxes to fund education.[35]

• • •

This publication and its conclusions are based on independent research and analysis conducted by NHFPI. Please email us at info@nhfpi.org with any inquiries or when using or citing New Hampshire Policy Points in any forthcoming publications.

© New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, 2024.

Endnotes

[1] See the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s Technical Assistance for Towns, Village, Districts, School Districts, Budget Committees, as well as the New Hampshire Municipal Association’s Federal Funding and Resources and NHFPI’s July 2024 presentation Funding Public Services in New Hampshire at the State and Local Levels.

[2] To learn more about these examples, see the Congressional Research Service’s reports from June 2018, Small Business Administration: A Primer on Programs and Funding, July 2022’s Small Business Administration (SBA) Funding: Overview and Recent Trends, and July 2024’s Medicare Overview.

[3] Based on General Fund appropriations as a percentage of the total allocated by the New Hampshire State Budget in Chapter 106, Laws of 2023.

[4] For examples of these grants, see the New Hampshire Department of Safety Grants webpage and the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Loans and Grants webpage.

[5] See an example of both infrastructure and waste management on the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Wastewater State Aid Grants webpage.

[6] See the New Hampshire Department of Education Local District Schools webpage.

[7] See RSA 52 for more information on village districts and Chapter 198, Laws of 2021 for an example of permitted, formalized cooperation between municipalities.

[8] See the New Hampshire Association of Counties The History of NH County Government and NHFPI’s August 2024 presentation Funding for Long-Term Services and Supports in New Hampshire.

[9] See the New Hampshire State Constitution and NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget.

[10] See RSA 9:4 and the Transparent NH government webpage How Government Finances Work.

[11] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 fiscal issue brief The Operating Budget Process, RSA 9:2, and RSA 9:3.

[12] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 Budget Orientationand the January 2017 document House Finance Committee Division Briefing, New Hampshire State Operating Budget.

[13] For more examples and discussion of the process, see NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, pages 9 and 10.

[14] In 2024, the Senate Finance Committee had seven members, while the House Finance Committee had 25 members, or more Committee members than there were members of the New Hampshire State Senate.

[15] See NHFPI’s May 2023 analysis Senate Ways and Means Committee Estimated Revenues $184.3 Million Higher Than House-Projected Revenues and May 22, 2017 blog post Senate Ways and Means Committee Increases Revenue Estimates for examples.

[16] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 fiscal issue brief The Operating Budget Process.

[17] See the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 fiscal issue brief The Operating Budget Process, the New Hampshire State Constitution Part Second, Article 44, NHFPI’s June 25, 2021 blog post Legislature Sends State Budget to Governor, NHFPI’s July 1, 2019 blog Services Funded at Lower Levels than Proposed After Governor Vetoes Budget, and NHFPI’s June 24, 2019 blog Committee of Conference Keeps Medicaid Reimbursement Rate Increases, Boosts Fiscal Disparity Aid in Final Budget Agreement.

[18] For examples, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s FY 2024-2025 Operating and Capital Budget webpage and the January 2023 Budget Orientation.

[19] See NHFPI’s June 2023 blog Senate Modifies State Budget Proposal, House Concurs with Senate Changes and Sends Budget to Governor.

[20] For more information and examples, see NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, NHFPI’s June 2023 presentation Examining the State Budget: Reviewing the Senate’s Proposal, NHFPI’s May 2023 issue brief The House of Representatives Budget Proposal for State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025, and NHFPI’s August 2021 issue brief The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023.

[21] See NHFPI’s February 2019 presentation New Hampshire’s State Budget and Families in the Post-Recession Economy, slide 2, as well as NHFPI’s August 2024 presentation Funding for Long-Term Services and Supports in New Hampshire and the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Medicaid Enrollment Data, accessed September 2024.

[22] See Chapter 106, Laws of 2023, page 722, NHFPI’s July 2024 presentation Funding Public Services in New Hampshire at the State and Local Levels, and NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, pages 13 and 14.

[23] For the division of State agencies by category, see the Governor’s Executive Budget Summary for Fiscal Years Ending June 30, 2024-2025, pages 18 and 19.

[24] See the Governor’s Executive Budget Summary for Fiscal Years Ending June 30, 2024-2025, pages 18 and 19, and NHFPI’s July 2024 presentation Funding Public Services in New Hampshire at the State and Local Levels.

[25] For more information about the most significant New Hampshire State Budget funds, see NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, pages 12 and 13 and the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 Budget Orientation, page 2.

[26] For more information about the most significant New Hampshire State Budget funds, see NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, pages 12 and 13 and the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 Budget Orientation, page 2.

[27] See Chapter 106, Laws of 2023, page 722, the Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2023 Budget Orientation, page 2, and RSA 198:42.

[28] See NHFPI’s February 2017 publication Building the Budget, pages 12 and 13.

[29] See NHFPI’s August 2019 fact sheet County Medicaid Funding Obligations for Long-Term Care and NHFPI’s August 2024 presentation Funding for Long-Term Services and Supports in New Hampshire.

[30] For more information on this section, see the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s October 2023 publication State Aid to Cities, Towns and School Districts.

[31] See NHFPI’s July 2023 presentation How New Hampshire Funds Public Services at the State and Local Levels, slides 72 to 75.

[32] To learn more, see the New Hampshire Municipal Association’s October 2022 publication Municipal State Aid and Revenue Sharing History and Trends.

[33] See NHFPI’s October 2023 fact sheet Education in New Hampshire: Fiscal Policies in 2023 and the New Hampshire Office of Legislative Budget Assistant’s January 2021 fiscal issue brief Calculating Education Grants Fiscal Year 2022 – District Public Schools.

[34] See NHFPI’s June 2023 presentation Examining the State Budget: Reviewing the Senate’s Proposaland the New Hampshire Department of Education’s Estimated Expenditures of School Districts 2022-2023.

[35] See U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data.