This second edition of New Hampshire Policy Points provides an overview of the Granite State and the people who call New Hampshire home. It focuses in on some of the issues that are most important to supporting thriving lives and livelihoods for New Hampshire’s residents. Moreover, the book addresses areas of key policy investments that will help ensure greater well-being for all Granite Staters and a more equitable, inclusive, and prosperous New Hampshire.

New Hampshire Policy Points is intended to provide an informative and accessible resource to policymakers and the general public alike, highlighting areas of key concerns. Touching on some important points but by no means comprehensive, each section within New Hampshire Policy Points includes the most up-to-date information available on each topic area. The facts and figures included within this book provide useful information and references for anyone interested in learning about New Hampshire and contributing to making the Granite State a better place for everyone to call home.

To purchase a print copy or download a free digital PDF of New Hampshire Policy Points, visit nhfpi.org/nhpp

The child care industry offers economic and child development benefits to families and New Hampshire as a whole, providing a critical support to the Granite State workforce.[1] In New Hampshire and elsewhere, however, there is currently a high need for child care services, but a lack of availability. Between 2018 and 2022, the state may have been short approximately 8,000 child care slots for children under six years old.[2] This mismatch would, in a typical market, create higher tuition prices and encourage the number of child care providers to increase. In reality, however, most programs cannot increase tuition enough to cover the true cost of high-quality care while still remaining affordable to families. These fragile economics result in parents paying relatively high and increasing tuition prices. At the same time, child care programs typically generate little or no profit, and early childhood educators receive low wages with few benefits.[3]

Cost and Assistance Programs

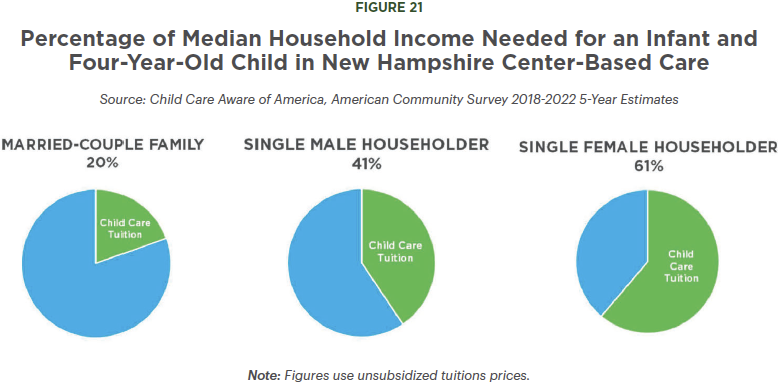

The average annual price for an infant and four-year-old child in center-based care in New Hampshire was $31,868 in 2023, a 12.5 percent increase from $28,340 in 2022.[4] Meanwhile, in 2018-2022, a New Hampshire married couple with children with median-income earnings ($145,289) would have spent nearly 20 percent of their household income on child care for an infant and four-year-old child at the 2022 price point. Median income earning single male ($69,830) and female ($46,283) householders with children spent 41 and 61 percent, respectively.[5] These percentages do not account for subsidized tuition through government or private programs, such as the New Hampshire Child Care Scholarship.

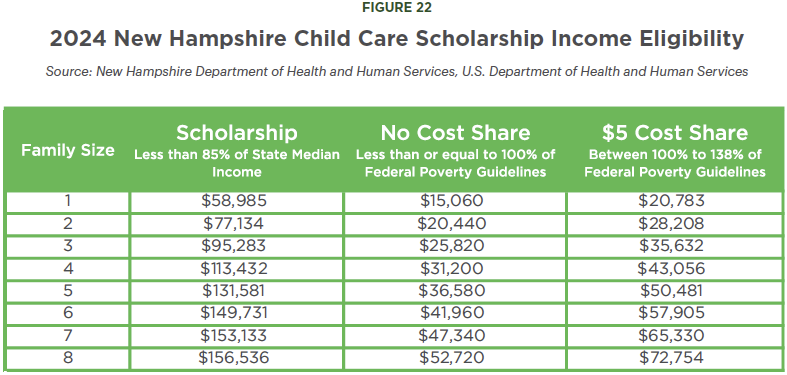

New Hampshire’s Child Care Scholarship is a state and federal partnership subsidy program that makes child care more accessible to eligible families with low and moderate incomes, helping enable parents or caregivers to look for employment, attend school, participate in a mental health or substance misuse treatment program, or participate in the workforce.[6] In the State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024-2025 State Budget, the Child Care Scholarship family income eligibility cap was raised to 85 percent of the State Median Income.[7] This means in 2024, a family of two is eligible for a scholarship if it earns less than $77,134, and a family of three less than $95,283, provided they meet all other eligibility requirements.[8] Family cost share rates, or the portion families are required to contribute toward the child care scholarship subsidy, were also lowered for scholarship recipients as part of the SFYs 2024-2025 budget so that families pay no more than 7 percent of their household income toward child care cost sharing.[9]

Since the eligibility expansion in January 2024, enrollment in this program, which served over 3,400 children as of July 2024, has increased nearly 29 percent.

Employment and Workforce

When parents cannot work due to unmet child care needs, the size of the potential workforce declines, and local and state economies suffer. U.S. Census Bureau survey data collected between August 2023 to August 2024 suggest that, on average, nearly 16,500 New Hampshire residents were not employed each month because they were caring for a child not in school or a child care setting.[10] In 2021, an analysis from the Bipartisan Policy Center estimated that New Hampshire households collectively lost between $400 million and $600 million in wages, or approximately $452 million and $678 million when adjusted for inflation to the first-half of 2024, respectively. When potential business losses and government tax revenues were added to the model, losses reached an estimated $44,100 to $66,816 per unavailable child care slot (or $49,858 to $75,522 in inflation-adjusted dollars for the first half of 2024).[11]

Beyond allowing parents to work, high-quality early care and education provide long-term benefits to children’s development and strong returns on investment, especially among children in families with low incomes. Key research suggests three- and four-year-olds who attend high-quality early care and education have better short- and long-term developmental outcomes, including enhanced language, literacy, mathematics, and socioemotional skills.[12] Moreover, longitudinal research suggests this type of education contributes to higher educational attainment, higher wages, lower health care costs, reduced need for public assistance, and lower likelihood of engagement in criminal activity later in life.[13]

Limited Supply

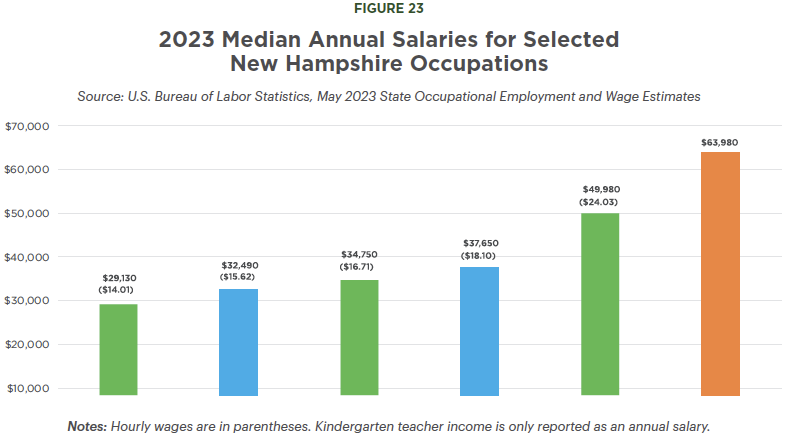

The early childhood educator shortage may be driven, in part, by low wages. In 2023, the median hourly wage for a New Hampshire child care worker was $15.62 an hour. This equates to $32,490 annually, only $2,490 more than the 2023 federal poverty guideline for a family of four ($30,000), and approximately half of the 2023 median salary for New Hampshire’s kindergarten teachers ($63,980).[14] New Hampshire’s preschool teachers earned a median annual salary of $37,650 in 2023, which is $2,900 more than retail salespersons ($34,750), but approximately $12,000 less than the median annual salary and wage income of all New Hampshire occupations ($49,980).[15]

Federal and State Investments

Since SFY 2016, over $555 million in federal and State funding has been deployed by the State to support the child care sector.[16] However, $145.9 million of those funds (26 percent) were one-time federal relief dollars associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.[17] An additional $15 million (3 percent) of the $555 million were one-time State funds for the child care workforce that were distributed during early SFY 2025.[18] As of the first quarter of SFY 2025, all one-time pandemic-related federal aid for early childhood education was required to be spent, leaving approximately $43.1 million dollars remaining for the sector until the next budget cycle. This equates to about 0.6 percent of the entire SFY 2025 budget of approximately $7.5 billion.[19]

Increased, consistent funding allocations toward New Hampshire’s early childhood education infrastructure may help ensure more long-term stability. The challenges faced by the early childhood education sector existed well before the pandemic, and on-going support could help ensure high quality early childhood education is available and affordable to bolster the state’s workforce, equip New Hampshire’s children with pre-academic and socioemotional skills, and grow the Granite State economy.

• • •

This publication and its conclusions are based on independent research and analysis conducted by NHFPI. Please email us at info@nhfpi.org with any inquiries or when using or citing New Hampshire Policy Points in any forthcoming publications.

© New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, 2024.

Endnotes

[1] See NHFPI’s February and May 2024 issue briefs, The State of Child Care in New Hampshire: End of One-Time Federal Investments May Reduce Industry Stability and The Fragile Economics of the Child Care Sector.

[2] Estimates calculated using U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey 2018-2022 five-year estimates, Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangements By Employment Status of Parents, B23008. The figure provided is the estimated number of children under 6 years old in New Hampshire with both parents, or their sole parent, in the labor force.

[3] See NHFPI’s May 2024 issue brief, The Fragile Economics of the Child Care Sector.

[4] See 2022 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire and 2023 Child Care Affordability in New Hampshire from Child Care Aware of America. For more information, see NHFPI’s May 2024 issue brief, The Fragile Economics of the Child Care Sector.

[5] Original NHFPI analyses using U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2022 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), S1903.

[6] See New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services’ NH Connections’ Child Care Scholarship information webpage and Eligibility for NH Scholarship slides.

[7] See NHFPI’s June 2023 blog, Senate Modifies State Budget Proposal, House Concurs with Senate Changes and Sends Budget to Governor and NH DHHS’s July 2023 Inter-Departmental Communication.

[8] See NH DHHS’s July 2024 Child Care Scholarship Income Eligibility Levels.

[9] See NH DHHS’s July 2024 Child Care Scholarship Income Eligibility Levels, p. 2.

[10] See the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data collections from Week 57 to Phase 4.1 Cycle 07.

[11] Note: These figures include the financial loss from the first year of the unavailable child care slot as well as residual, cumulative effects related to those initial financial losses over a ten-year time horizon. See the Bipartisan Policy Center’s 2021 report, The Economic Impact of America’s Child Care Gap, in particular, p. 11 for an explanation of cumulative impacts. Figures adjusted for inflation using CPI-U New England.

[12] See Society for Research in Child Development and Foundation for Child Development’s October 2013 summary Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education, Child Development Perspectives’ 2022 peer-reviewed article The Promise and Purpose of Early Care and Education, National Bureau of Economic Research’s 2021 working paper The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston later published in 2022 under the same title in the peer-reviewed journal The Quarterly Journal of Economics, and the Journal of Political Economy’s 2020 peer-reviewed article Quantifying the Life-Cycle Benefits of an Influential Early-Childhood Program.

[13] See the Tax Policy Center’s September 2023 publication The Return on Investing in Children: Helping Children Thrive.

[14] See U.S Bureau of Labor Statistic’s May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimatesfor New Hampshire and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation 2023 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (except Alaska and Hawaii).

[15] See U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics’ May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimatesfor New Hampshire.

[16] NHFPI analysis of HB1 for SFYs 2016-2017, 2018-2019, 2020-2021, 2022-2023, 2024-2025, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Division of Economic Stability’s August 21, 2023 report, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023, and SFYs 2024-2025 HB 2, p. 147.

[17] Figure derived using New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services Division of Economic Stability’s August 21, 2023 report, New Hampshire Child Care COVID Funding, and NH Connections’ Child Care Operating Expense Reduction (CCOER) Grant Program Application Overview as of October 24, 2023.

[18] See Department of Health and Human Services’ document, Child Care Workforce Grant State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025 as of January 2, 2024.

[19] NHFPI analysis of Chapter 106 HB 1-A – Final Version. For more details, see NHFPI’s February 2024 issue brief, The State of Child Care in New Hampshire: End of One-Time Federal Investments May Reduce Industry Stability.